1 My Father Was a Socialist

IN JULY 1896 THE DEMOCRATIC National Convention was held in the grand Chicago Coliseum. Forty thousand citizens filled the Coliseum’s seven-acre interior from the floor to the wings as William Jennings Bryan took the stage. A member of both the Democratic Party and the Populist Party, Bryan was the progressive candidate of the common man.

“Upon which side will the Democratic Party fight,” he asked, “upon the side of ‘the idle holders of idle capital’ or upon the side of the struggling masses?”1

When Bryan finished his speech, men hooted and threw their hats. Women waved handkerchiefs. The cheering lasted for thirty minutes, while delegates hoisted Bryan on their shoulders and carried him around the floor.

As Bryan was departing on his buggy, a man chased after him. This man was a laborer—lean, gaunt, and thirty-seven years old. Just a few years before, he had failed as an orange grower in Florida and had come to Chicago to work as a carpenter.

The man made it to Bryan’s buggy. He extended his hand in admiration, and Bryan shook it. For the rest of his life, Elias Disney would tell his children how he got to shake the hand of William Jennings Bryan.2

Bryan became the presidential nominee for both the Democratic and Populist Parties. But after he lost the 1896 election to Republican William McKinley, the Populist Party started to disintegrate, polarizing liberal voters. Many of Bryan’s supporters followed him into the slightly more moderate Democratic Party. The more radical contingents eventually gravitated toward the newly formed Socialist Party and its front man, Eugene Victor Debs. Faced with the choice, Elias Disney went with Debs and became a member of the Socialist Party.

“My father was a Socialist,” Walt Disney would say at the comfortable age of fifty-eight. Walt and his interviewer, journalist Pete Martin, had something in common: each could say his father was “a Debs man.” Walt would recall it with dissociated wonder from his perch of commercial fame and fortune. But during the years growing up in his father’s home, the Socialist Party was the predominant influence—not only politically but as a way of life. Elias Disney allowed his politics to dictate how he managed his money and his family as well.3

In January 1905 Debs led a Chicago convention for a larger Socialist movement. As it became more radicalized that summer, Debs stepped away and a new, more militant leader stepped up. His name was William D. Haywood, and the group, the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), was later suspected of being behind a terrorist bombing that almost killed Walt Disney.

Crowded, smoky—that was Chicago in 1906. It was the second most populous city in the United States, with around 1.9 million people.4 Horse-drawn buggies clip-clopped through the streets, and gas-powered streetlamps burned every night. The Industrial Revolution was still in full swing, and factories along the skyline billowed exhaust into the sky. For a four-year-old child named Walter Elias Disney, that was life.

Walter, born December 5, 1901, was the youngest of four sons of Elias and Flora. Elias had been born in Ontario, Canada, the son of Irish immigrants; Flora was from Ohio and was of German and English descent. Their sons Herbert, Ray, and Roy predated Walter by several years. Two years after Walter came his baby sister Ruth.

Crime was rampant in the Disneys’ Chicago neighborhood, and Elias’s brother Robert beckoned him to the Missouri farmland. Fearing for the safety of his two eldest sons, now teenagers, and with hopes of farming a fortune, Elias moved his family to a farm in Marceline, Missouri.

The town was the home to fewer than four thousand citizens and was unlike anything Walter had ever known.5 His family moved into a white farmhouse with green trim on forty-five acres of land. There were fruit trees, berries, wild animals, creeks and brooks, and a main street that led into the quaint small town. Past the farmhouse was a tall and twisted cottonwood tree that Walter dubbed his Dreaming Tree, and he and Ruth would climb its branches or just sit in its shade in contemplation.6 Walt Disney would later credit Marceline as his primary creative inspiration, saying, “Those were the happiest days of my life.”7

Because it was easier for Elias and Flora to manage, Walter began school at the same time as his little sister Ruth. Thus, while he had two extra years of childhood freedom, he would remain old for his grade throughout his schooling.

He could remember things from his childhood with a clarity that astounded even his own family. There was the bliss of receiving his first drawing tablet and crayons from his Aunt Maggie and her endless compliments on Walter’s artistry.8 There was the wisdom of his elderly neighbor, Doc Sherwood, who warned him, “Don’t be afraid to admit your ignorance.”9

This was advice that Walt would cleave to throughout his life. As an adult, he would put almost blind trust in his appointed advisors. This, he figured, would free his creativity, like the unhindered child in Marceline.

That’s not to say that that child couldn’t get into big trouble. Out of a rain barrel he scooped wet tar and smeared a mural on the side of the white farmhouse. Flora gave him a “bawling out,” but Elias spanked Walter with his leather razor strop.10

Elias was strict in his ethos and in his authoritarianism. “Churchy,” a neighbor called him.11 Yet Elias, at least in those days, was able to express his own creativity as an amateur musician. Some nights, the family gathered at Doc Sherwood’s, and Elias played his fiddle while Mrs. Sherwood accompanied on the piano.

Elias hosted his own gatherings at the Disney farmhouse, but their purpose was to spread the doctrine of agricultural socialism. He was a member of the American Society of Equity, a socialist cooperative of midwestern farmers. It pressured lay leaders like Elias to run meetings and enlist other members. “Dad was always meeting up with strange characters to talk socialism,” remembered Walt. “They were tramps, you know? They weren’t even clean.” Flora tried to support her husband but fed the strangers on the doorstep to keep them out of the house.12

Nonetheless, the Equity had many harsh critics, even among the progressives in the farming community. For one thing, the Equity never committed to concrete goals for crop-withholding, price-fixing, or striking; its tactics remained strictly theoretical. For another, the Equity’s founder was neither a laborer nor a farmer but an Indianapolis businessman and the editor-in-chief of an agricultural newspaper. Most important, the Equity pocketed the money paid in membership dues, whereas a bona fide union uses dues to pay its leaders. Instead of receiving a steady paycheck, Equity organizers like Elias were paid on a commission basis. He was explicitly instructed to grow membership through the Equity’s aggressive methods of word of mouth and chain letters—which, by 1940, were remembered as “myriad schemes.” The Equity required a $1.50 membership fee, $1 annual dues, and a subscription to the Equity newsletter. At the time of Elias’s involvement, the Equity had already been publicly condemned as the “Society of Inequity.”13

Even Walt remembered his dad as victim of his own credulity. “He believed people,” Walt said later. “He thought everybody was as honest as he was. He got taken many times because of that.”14

This was Walt Disney’s first encounter with the organized labor movement.

Elias must have been awfully unsuccessful as a Socialist organizer; he couldn’t even convince his own family of the movement’s merits. By 1910 the Disney farm was failing, and Elias demanded everyone pool their earnings together for the family farm. The eldest Disney brothers, Herb and Ray, resented this passionately. Little Walter was witness to many a scorching argument between his big brothers and his father. One evening, Herb and Ray returned to the Disney farmhouse having spent half their earnings on new pocket watches. Elias was livid. The fury that erupted was the final straw for Herb and Ray. The next day they emptied their bank accounts and ran away from the Disney home, leaving the rest to manage on their own. Elias’s stubbornness had broken the family.

Without the eldest brothers’ help, the family sank more quickly into debt, and soon they had to sell the farm. That November of 1910, eight-year-old Walter and sixteen-year-old Roy had to post bills around town for the family’s estate sale. For Walter, it was heartbreaking.15

In May 1911 the family moved to Kansas City, Missouri, a city with a population of a quarter-million people. The Disneys lived in one of the small houses on a densely occupied street,16 a far cry from the paradise of a forty-five-acre farm. Their “orchard” was now a single tree; their vast fields were now a single small vegetable garden.

Hungry for an income, Elias bought a Kansas City Star paper route. He assigned the newspaper deliveries to himself, Roy, and Walter. Now Roy and Walter had to wake between 3:30 and 4:30 in the morning, go to the printing plant to pick up their papers, deliver them to each house with a pushcart, be at school when the first bell rang, and then leave school a half hour early in the afternoon to pick up and deliver the evening editions. On Sundays the paper was so thick and heavy that Walter needed to double back to the headquarters to fit a second load in his pushcart. This was in addition to his regular household chores.

Meanwhile, Elias, at fifty-two, had stopped playing the fiddle and started investing every penny his family earned into a struggling jelly and juice company called O-Zell.17 To earn his own pocket money, Walter covertly hired himself out to local shops as a handbill distributor, and clocked in at a drugstore during his midday recess. Only in secret could he keep a penny for himself.

Unsurprisingly, Walter became an eager escapist, particularly when it came to the movies. When Charlie Chaplin debuted, his Little Tramp character in 1914, Walter was an instant fan. Like the Tramp, Walter had a coy disrespect for authority. He would sneak out to his friend’s house at night18 and smuggle a field mouse to school in his pocket.

Walter continued drawing, sometimes making doodles in the margins of his books so that when he flipped the pages the images seemed to move.19 He also copied the comic strip from his father’s Socialist newspaper, the Appeal to Reason. As he remembered, “The Appeal to Reason would come to our house every week. I got so I could draw ‘Capital’ and ‘Labor’ pretty good—the big, fat capitalist with the money, maybe with his foot on the neck of the laboring man with the little cap on his head.”20 This comic strip was called The New Adventures of Henry Dubb by cartoonist Ryan Walker. The anti-union laborer’s clownish expressions and stubbornness made him the hapless butt of ridicule.

The New Adventures of Henry Dubb, by Ryan Walker, from Appeal to Reason, April 25, 1914. Young Walt Disney copied this comic strip to practice his drawing.

After one year of delivering newspapers, Roy found work as a bank teller, while Walter continued as a paperboy into his teens. In January 1917 the Kansas City Convention Center hosted a Newsboy Appreciation Day sponsored by the Kansas City Star, offering free movie screenings for newsboys. Thousands flocked to the building. Walter had just turned fifteen and was among the oldest in attendance.

He landed a seat in the gallery. Four screens were placed in the center of the round, each with its own projector, intending to synchronize on each side to all the surrounding children.21 The lights dimmed. The room hushed. The organist began the film’s overture, and the projectors began to roll the silent live-action film, 1916’s Snow White. Walter Disney sunk deep into his chair, quietly drifting into a world of silver-screen fantasy.

Because the Chicago-based O-Zell company was close to bankruptcy, Elias thought it wise to help revive it. In March 1917 he sold Walter’s paper route and moved the family—himself, Flora, Walter, and Ruth—back to Chicago.

At this time, Eugene Debs, leader of the Socialist Party, was touring the country, protesting the Great War that the United States entered on April 6. The Socialist Party adamantly argued that war was waged by the rich but fought by the poor.22 President Woodrow Wilson was not pleased. On June 15, Congress passed the Espionage Act, declaring it treasonous to protest the war.

That same month, Roy defied his father’s politics and volunteered for the US Navy. The family saw Roy off to war, and his brother’s enlistment struck Walter as the most noble thing he had ever witnessed.

Chicago had changed in the eleven years since Elias and Flora had lived there. Most significant was the presence of the Industrial Workers of the World. Eugene Debs’s once modest Socialist convention had swelled to tens of thousands, largely due to the Russian immigrants who had come after the Communist Revolution led by the Workers’ and Peasants’ Red Army. The IWW had a reputation for intimidation, sabotage, violence, and vandalism, planting bedbugs in hotels, burning down wheat fields along with their threshers, razing lumberyards, and destroying granary machines.

The IWW protested the Great War in swarms that outnumbered law enforcement. Members of the IWW sneaked aboard military trains and taught US soldiers how to poison fellow enlisted men. (Uncooperative enlistees were reportedly thrown from the trains.) At night, machines at artillery plants were jammed. The culprits left behind stickers bearing the insignia of the IWW: a snarling black cat ready to pounce—presumably on an unsuspecting mouse.23

The icon of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), under the leadership of William Haywood.

During the 1917–18 school year, Walter Disney was known as the class cartoonist and amateur magician.24 Elias, however, thought his son was wasting his time. “He never understood me,” remembered Walt. “He said, ‘Walter, you’re not going to make a career of that, are you? I have a good job for you in the jelly factory.’”25 Every day after school, Elias had Walter contribute to the family collective by doing odd jobs at the O-Zell plant. By the time the school year was over, Walter wanted to have nothing more to do with O-Zell. In June 1918, Eugene Debs was arrested and charged with ten counts of sedition for protesting the Great War.

That summer, as Debs waited for a verdict, Roy visited Chicago on military leave. Walt was tremendously impressed seeing his brother in uniform. By the time Roy returned to duty, Walter had made up his mind to join the war effort too. He was two years shy of the age minimum of eighteen, so he set out to find work instead. He landed a job in Chicago’s downtown Federal Building as a substitute mail carrier.

Elsewhere in downtown Chicago, one hundred IWW members were tried and convicted of conspiracy. Fifteen of them, including leader William “Big Bill” Haywood, were sentenced to twenty years at Leavenworth Penitentiary, the country’s largest maximum-security federal prison.26 The office of the presiding judge, Kenesaw Mountain Landis, was located in the Federal Building, several floors above where Walter Disney worked.

On the evening of Wednesday, September 4, 1918, Walter was in the lobby of the Federal Building ready to leave. Suddenly at the main door was a flash and a deafening explosion. Brick and stone were blasted in the air. Walter was a breath away from the blast. “I missed that darn thing by about three minutes,” he remembered.27

Witnesses reported seeing an occupant of a passing car hurl an object at the Federal Building’s entryway. The police would call it a “death bomb.” Four people were killed; seventy-five were injured. The police rounded up nearly a hundred members of the IWW. No charges were filed, but in the court of public opinion, the IWW was guilty. Unfortunately for the Socialist Party, papers linked the IWW to Eugene Debs.28

It was then, with unprecedented resolve, that Walter defied his father’s politics and joined the war effort. He learned that the Red Cross Ambulance Corps allowed seventeen-year-olds to enlist, so he got Flora to sign for him, and he doctored his birth date by a year.

On September 12, Eugene Debs was found guilty of undermining the American war effort. On September 16, Walter Disney officially joined it.29

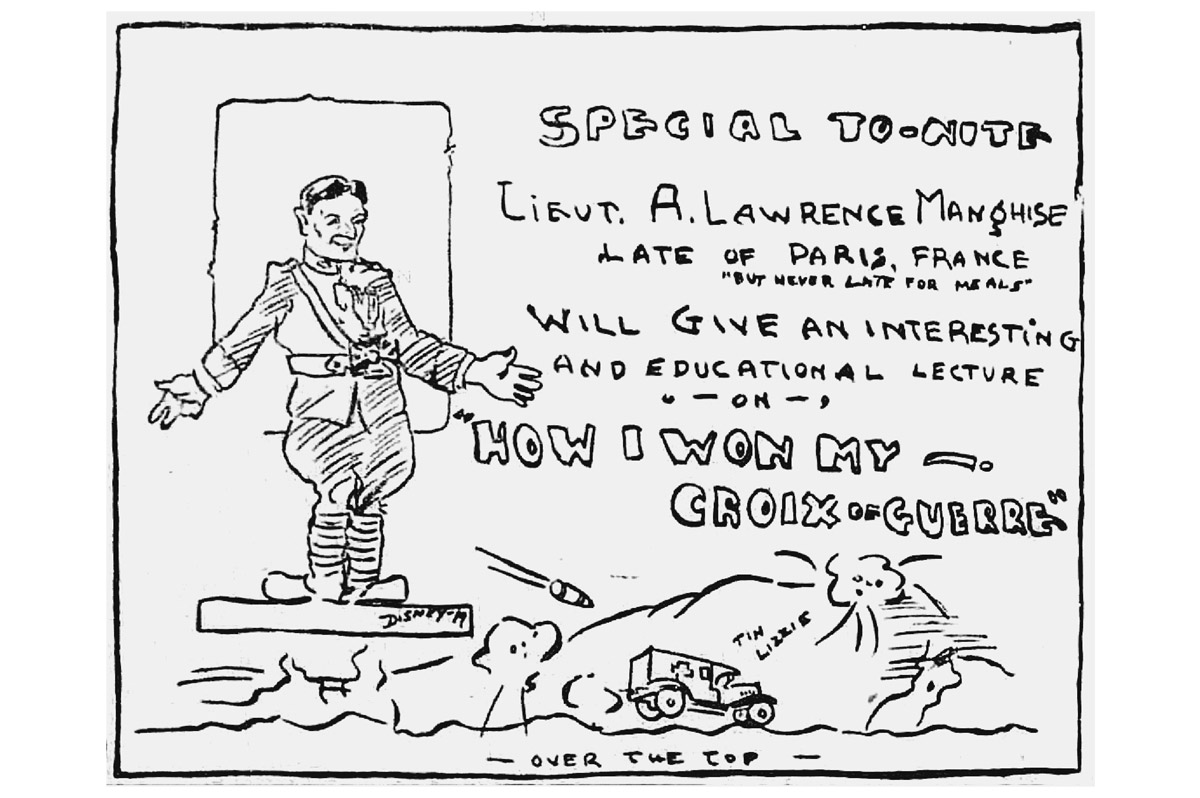

By the time Walter arrived in Europe, the war was over. Armistice was declared on November 11, and Walter was assigned to help with the reconstruction of France.30 He would forever recall his days in France with an air of nostalgia. For the first time his artwork found a wide adult audience. He illustrated the side of his ambulance, and during his adventure Walter gave away drawings he made of the men in his unit.31

He returned to the United States on October 9, 1919, measuring five feet, ten inches tall. A war veteran, he was now in stark contrast to his father. Whereas Elias never drank whiskey, smoked, or cussed,32 his son now did. As if distancing himself further, he now went by “Walt.”

With little left in Chicago that piqued Walt’s interest, he left the city—and Elias—behind.

A drawing by Walt Disney, age seventeen, for one of his fellow soldiers, as printed in the Colton Daily Courier, July 23, 1941.