13 A Drunken Mouse

Starting in September 1935 the Disney studio began constructing a building across the street from the main gates, at 2710 Hyperion Avenue. It was called the studio’s annex, and it would replace the bullpen as the place for new hires to try out their inbetweening skills. It was also the newly designated place for Don Graham’s art classes. When the annex was finally complete in November,1 it bore a facetious sign above the door: DON GRAHAM MEMORIAL INSTITUTE. (Graham was very much alive.) Beneath that was inscribed SEMPER GLUTEUS MAXIMUS, or as the animators translated, “Always Your Ass.”2

Besides classes in figure drawing and action analysis, the studio scheduled lectures in the elements of cartoon-making. The Disney animators were so advanced that literally no animation experts outside the studio could meet their needs. Therefore, they began to hold formal lectures for each other.

On November 27 Walt addressed a group of story artists, animators, and a stenographer. “Now that you have attended two lectures on the personality, continuity, technique, et cetera, of the animated cartoon,” he said, “we got the happy idea that—before going any further—we would put these lectures to some practical use by applying this new knowledge to a story.”3

Beside Walt stood Dr. Morkovin and the head story man of the next cartoon (soon to be called The Country Cousin), Dick Rickard. Walt, director Wilfred Jackson, and the story team had been working on a new cartoon based on “The City Mouse and the Country Mouse” children’s story. Several artists sat before Walt that day, including some of the art-school graduates who had sprinted up the ranks.4

Dr. Morkovin lectured about comedy in the cartoon, and Rickard discussed the story. In it, the Country Mouse visits the City Mouse’s opulent home, gets drunk on champagne, kicks the housecat, and flees back to the country. The artists made their comments. Babbitt scribbled down their suggestions with his pencil, noting who offered each idea.

Babbitt was silent at the meeting. His $1.29 civil court case against the hardware store had been dismissed. But the outcome hardly seemed relevant anymore. The lawsuit itself strengthened Babbitt’s reputation as the studio’s man of principle.

Walt continued expanding his art school with film presentations. He rented theater space in North Hollywood, and every Wednesday night he presented a movie to stimulate creative growth.5 As per the rule, the front two rows were reserved for supervisors and directors. The other artists would dare not sit in one of these seats, even if an entire row was vacant.

The screenings included everything from Charlie Chaplin comedies and Fred Astaire musicals to masterpieces of German expressionism like Nosferatu. One unfortunate night, an underwater nature documentary was shown, which displayed one large aquatic specimen with a vertical slit and pink, labia-like folds. The Disney artists began chuckling as the folds slowly opened. When the folds had fully spread apart, the room was filled with uncontrollable laughter. Walt was fuming; he immediately terminated the Wednesday night screenings.6

Friday night’s figure-drawing class was exclusively for supervising animators. During one such class in December 1935, Bill Tytla paid particular attention to the brunette model.

The models of Doris Harmon’s Southern California Modeling Club fought for Disney modeling jobs. They had an eye for the young men at Disney. Babbitt had already had a relationship with the model Sändra Stark, and she told her fellow model, Adrienne le Clerc, of Babbitt’s attractive friend and housemate. He was also a supervising animator and a “wild Russian.” Adrienne requested the Friday night slot so she could see him for herself.

The two were lovestruck. A romance between the artist and the model was born.7

For several weeks, Bill and Adrienne were inseparable. On Sunday afternoons, they arrived at the house on Tuxedo Terrace with foodstuffs from a Japanese produce stand. But the home was now filled with the sound of Babbitt’s amateur piano playing, banging out Moonlight Sonata on the living room’s baby grand.8

Babbitt was managing his emotions as best he could. It was not only that Babbitt was single and Tytla wasn’t. He was also silently grieving the death of his father, Solomon Babitzky, who died on January 17 at age fifty-eight.9 Babbitt never joined Bill and Adrienne for dinner, instead opting to leave them and return on his own time.10

It would have been easier to avoid them if his room had a separate entrance, as Tytla’s did out back. To have his own secret door, like the speakeasies of his youth, would have been the ultimate convenience.

The first animation for the seven dwarfs had been assigned right before Christmas 1935, and the first animation of Snow White herself began in January 1936.11 Walt made good on his promise to Babbitt and assigned him a major section: supervising animation for the Wicked Queen, in addition to animating some Dopey scenes. Fred Moore and Bill Tytla would supervise the dwarfs’ animation.12 Norm Ferguson would animate the villain as an old hag. Woolie Reitherman would handle the Magic Mirror, a relatively minor assignment. He and the other art-school graduates shared most of the smaller roles, with perhaps the biggest among them going to Frank Thomas, who had to animate the dwarfs mourning the recumbent princess.

Walt insisted on perfecting each sequence with the director and supervisors until it was ready. He didn’t seem concerned that time was money. More than once, Roy walked in on Walt with director Dave Hand, complaining that they were overspending. Walt responded sharply, “Roy, we’ll make the pictures, you get the money. Now goodbye, I’m busy.”13

As sequences for Snow White progressed through the Story Department, the animators kept busy on shorts. In early 1936 Babbitt completed much of his Goofy animation for Moving Day. Woolie Reitherman animated most of the Peg-Leg Pete scenes in the cartoon.14

When Babbitt previewed his test animation at the studio, he was surprised by the reaction—it was how Goofy expressed his emotions that got the biggest laughs, and not the gags themselves.15 Personality had proven to overshadow the slapstick.

Like Goofy’s physicality, Babbitt made his own physical health a public affair. He regularly promoted pop health science. For a period, he preached the benefits of eye exercises to strengthen one’s vision.16 One week he wouldn’t stop expounding on the benefits of hydration and pure drinking water. Fortunately for him, every animator’s room had its own Sparkletts water cooler. One afternoon, as Babbitt confidently drank from his cooler, he suddenly saw three live fish surface from its shadowy depths. Babbitt spat and raised hell, but the prankster wisely never came forward.17

Now that the studio’s education initiative was underway, lead animators were scheduled to attend story meetings and sweatbox sessions for all the shorts. On February 5, 1936, Babbitt and Les Clark sat in a story meeting with writers and directors (and a stenographer) for the cartoon starring Abner, the country mouse, and Monty, the city mouse. They were talking about the climax, in which the mouse breaks a porcelain china cat, when Babbitt interjected, “In the opening of the picture, when the mouse knocks on the door, instead of Monty coming out and shushing him, why couldn’t Monty have his own little door made of brick? Have it open up like a speakeasy door.”

The writers hadn’t intended on giving the mouse his own door. “We would like to avoid such things,” said head story man Dick Rickard. “We didn’t want to give the impression that Monty had his own house. . . . I don’t like the idea.”

That closed the topic. Discussion shifted and Babbitt spoke up again.

“I would like to see the first part of the china cat taken out,” he said. “It has no value. You are trying to build up the fact that Abner imitates his city cousin but there should be some other reason for Abner disturbing the real cat. The idea is too forced.”

The story men stood by their script. “I think the idea is good because Abner is drunk,” Ted Sears said.

“I like the idea,” said Ben Sharpsteen.

The topic changed once again, and the meeting continued for another twenty minutes.18

Though unanimously spurning Babbitt’s ideas outright, the story team realized that Babbitt was right and incorporated his ideas in the end. Babbitt was no longer merely an animator. He was now a member of Walt Disney’s creative elite.

On the morning of March 17, 1936 (twelve days after accepting an Academy Award for Three Orphan Kittens, directed by Dave Hand), Walt participated in a story conference for the City Mouse–Country Mouse cartoon. The topic was Abner the Country Mouse’s encounter with a glass of champagne. Babbitt attended the conference as well.

“We see him drinking,” said Walt. “He is making a lot of noise. Get a quick cut to Monty—just a flash—then back to Abner and how he is right in the glass. The last thing he does is to suck the champagne right from the bottom of the empty stem. Get a big ‘hic!’ from him.”

Babbitt spoke next. “When he tries to get out of the glass he could get to the very rim, only to slip and go down into the stem.”

“I don’t see the mouse that small,” Walt said. Then he suggested, “Get a sound of a sink emptying when Abner is sucking up the champagne!”

The two were on a roll now, and for the next several minutes, Walt and Babbitt riffed, building on ideas for drunken Abner and the wineglass.19

Every day Walt gauged the progress of Snow White, and there were not enough hands to finish it by its deadline on Christmas 1937. The studio needed hundreds of new artists, and each of them required several weeks of training. Ads for Disney jobs started appearing in newspapers in February,20 and soon young people across the country began applying. Art instructor Don Graham and inbetweening supervisor George Drake left Hollywood on March 19, 1936, for a two-month hiring spree at Disney’s Manhattan recruitment office.21

Near the end of March,22 Babbitt walked to director Wilfred Jackson’s music room and picked up his animation assignment for the City Mouse–Country Mouse cartoon. Babbitt and his friend Les Clark were assigned the two largest sequences: Clark would handle most of Monty the City Mouse, and Babbitt would animate drunken Abner. This was a chance to show real comedy and pantomime through a character’s personality and thought process.

Walt found Babbitt in Jackson’s room picking up the assignment. Walt told him that he hoped Babbitt would do as good a job as he did on Moving Day.23 With a straight face, Babbitt replied that he’d try, but he was going to need a research fund for this assignment.

Walt’s face hardened. He demanded what Babbitt meant by a “research fund.” The front office was already complaining about expenses!

“If I’m going to do a drunken mouse,” said Babbitt, “I ought to know what it feels like to have alcohol in my system.”

Walt stood there, raising one eyebrow and lowering the other—then left the room without another word. Babbitt wasn’t sure if Walt got the joke.24

As Babbitt began animating, he struggled with himself. He was among the top animators of the studio—and therefore, of the entire industry—yet he felt his work on Abner was falling short in many ways.25

Like his character analysis of Goofy, Babbitt inserted himself into the psyche of the cartoon mouse. “The important thing in analyzing a scene when you pick it up,” he told others then, “is first of all to know your character. The drawing should mean something to you—a certain definite personality. You try to make yourself feel the way that character would feel under the same circumstances, and you try to think as he would think. Your animated figures must think. If they don’t, they will go static.”26

He put his pencil to his paper and began to draw.

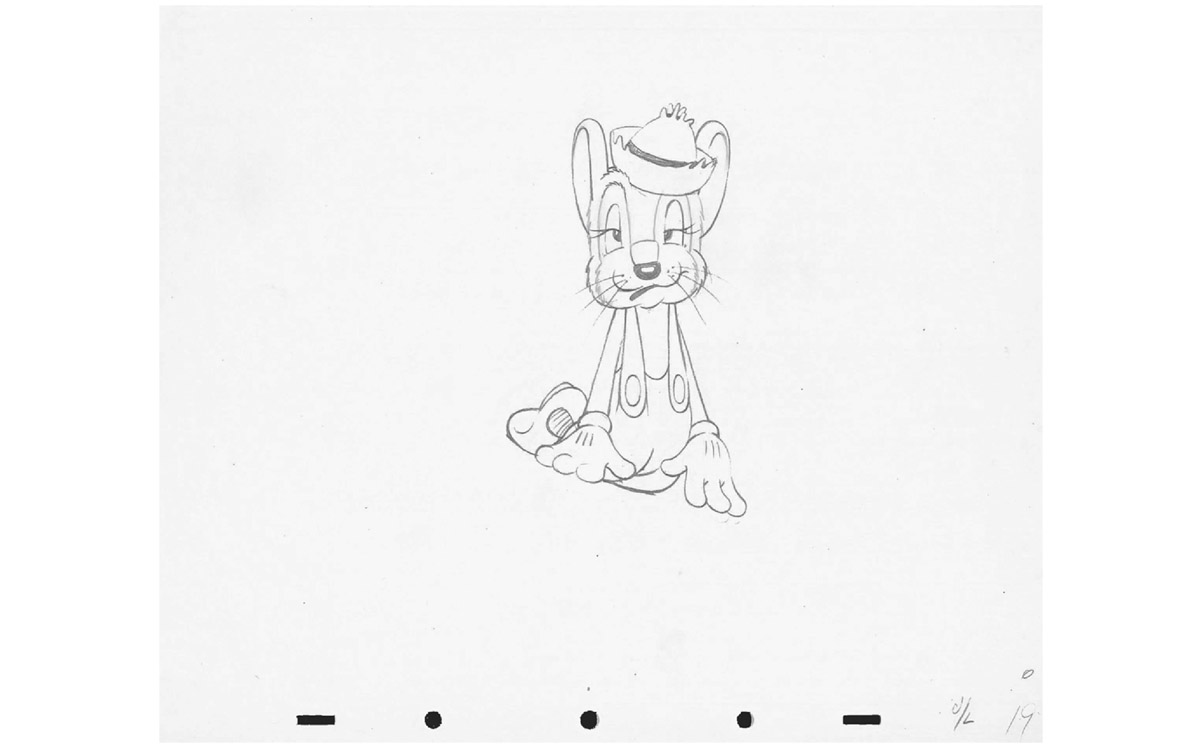

Drawing of drunken Abner in the wineglass from The Country Cousin. © The Walt Disney Company