14 Disney’s Folly

In the local restaurant during lunch, Marjorie Belcher sat with Babbitt and the other animators. As a parlor trick, Babbitt would sometimes hypnotize on command. Marge dared him to try it on her. As much as he tried, his powers of hypnosis were useless on her. She merely laughed.1

A generous new policy went into effect on April 1, 1936. It was known around the front office as “Adjusted Compensation,” but the animators called it the “Bonus Plan.” According to this new incentivizing system, all animation would be rated. Work that was merely excellent earned an A-minus. Work that was excellent and innovative earned an A. Directors would award all the grades, and Walt would sign off on them. The grade, plus an amount of profit from the short, would merit a cash reward.2

The staff may have been skeptical at first, but within the first week, the bonuses were distributed. On April 7 Babbitt received a lump sum beyond any previous bonus. His grade A work for On Ice, Broken Toys, and Mickey’s Polo Team earned him $958.00.3

It hardly mattered that the metrics for determining the amount remained confidential, that only management knew the criteria. It was unlikely this idea came from Roy, who tried to conserve costs at every turn. Rather, it had all the trappings of someone who wanted to control others without claiming accountability, a strategy used by the chief legal counsel and now senior vice president, Gunther Lessing.

A new Mickey Mouse cartoon called Mickey’s Amateurs was in the story phase. Mickey would host a radio program for amateur performers. The plot was a string of clownish musical gags—perfect for the musical clown in the writer’s room, Pinto Colvig, to codirect. The finale would be Goofy as a one-man band, just like Art Babbitt’s brother Ike. Colvig would voice the character, Babbitt would animate him, and Goofy would play a clarinet (and many other instruments) in full bandleader regalia. Goofy had to march on stage and twirl his baton. For reference, Babbitt filmed an attractive majorette marching and twirling a baton in the studio parking lot.

While Babbitt conducted his own action analysis with his camera, the studio pushed on with its Thursday night Action Analysis class. Topics now ranged from “Anticipation” to “Color Composition” to “How to Maintain Interest in a Spectator.” Speakers included Dave Hand, Don Graham, and Dr. Morkovin. But this art school wasn’t cheap to maintain, and neither were the constant pencil tests and reworking of scenes. Roy and Walt openly bemoaned the studio’s mounting expenses. In May 1936 Roy negotiated with the Bank of America to increase their loan from $250,000 to $630,000.4

The bank was reluctant. Hollywood was skeptical about whether audiences would sit still for a feature-length cartoon. Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs was being called “Disney’s folly” around town. Many of the bank’s contacts in Hollywood discouraged them from sinking any more money into Snow White.5 Walt’s employees knew the risk and took their chances.

However, one did not. That spring, Babbitt’s friend Hardie Gramatky left Disney to pursue his dream as an independent artist in New York.6 Around that time, Tytla moved out to cohabitate with Adrienne. Babbitt’s relationship with his friend Hal Adelquist had changed too. The one-time errand boy who had introduced Babbitt to Marge was promoted to assistant director of Snow White around June. He was now the eyes and ears of director Dave Hand.7

Babbitt’s animation on the shorts had become among the most praised in the field. When Moving Day premiered on June 20, 1936, it was a hit with audiences and animators alike. Babbitt imbued Goofy with a kind of new animation that excited the whole industry; Warner Bros. cartoon directors got hold of a copy and ran it frame by frame in their Moviola just to study it.8 As Babbitt completed his animation on the City Mouse–Country Mouse cartoon, now called The Country Cousin, he received his Moving Day bonus—a whopping $1,204.9

On September 23, after returning from a New York vacation, Babbitt participated in the studio’s new Training Course Lecture Series, addressing the new inbetweeners and assistants.

“The animator must have innate fine taste and sensitivity,” said Babbitt, encouraging them to use the whole of their experiences as creative influence. He then began discussing timing—how a director’s notations were to be followed closely and scene-padding was absolutely prohibited. He held up an exposure sheet as an example—and it unfurled like a scroll, tumbling past his knees and onto the floor. The artists laughed—they knew Babbitt’s reputation for padding.10

“The animator must have a feeling for direction and not just follow orders,” he said. As animators, you will have to be your own director too.” He showed Goofy’s walk from Moving Day, frame by frame, saying, “Later on when you know the basics, experiment once in a while, and try to break some rules. It’s lots of fun and you will be surprised at some of the results you will get. It’s fun breaking rules, anyway.” Only Babbitt could weave into his lecture a treatise about insubordination.

He concluded with this message of integrity and hope, revealing the studio’s one-for-all mentality: “This business has been treated as a racket, by some people, to squeeze nickels out of it. But you can—with the aid of God, a fast infield, and the squelching of Hearst—create an art that will pay you handsomely in nice great big dollars—unless we go broke in the meantime.” Like a ship of explorers, they would either share in Snow White’s rewards or sink together.11

That October, Walt and the filmmakers watched the preview of The Country Cousin from the back of the Alexander Theatre.12 It was another hit. The two mice, without any dialogue, achieved perfect acting, rich in personality.

Walt and the creative team gathered outside to debrief. Nearly everything about the cartoon was flawless, and Babbitt was able to pull off a drunken mouse, even without his proposed “research fund.”

There was a twinkle in Walt’s eye. He hadn’t forgotten. “Hey Art,” he said as the group dispersed, “how ’bout a cocktail?”

Babbitt paused, meeting Walt’s smile with his own. “No thanks,” he retorted, “I’ve got a date with a blonde.”13

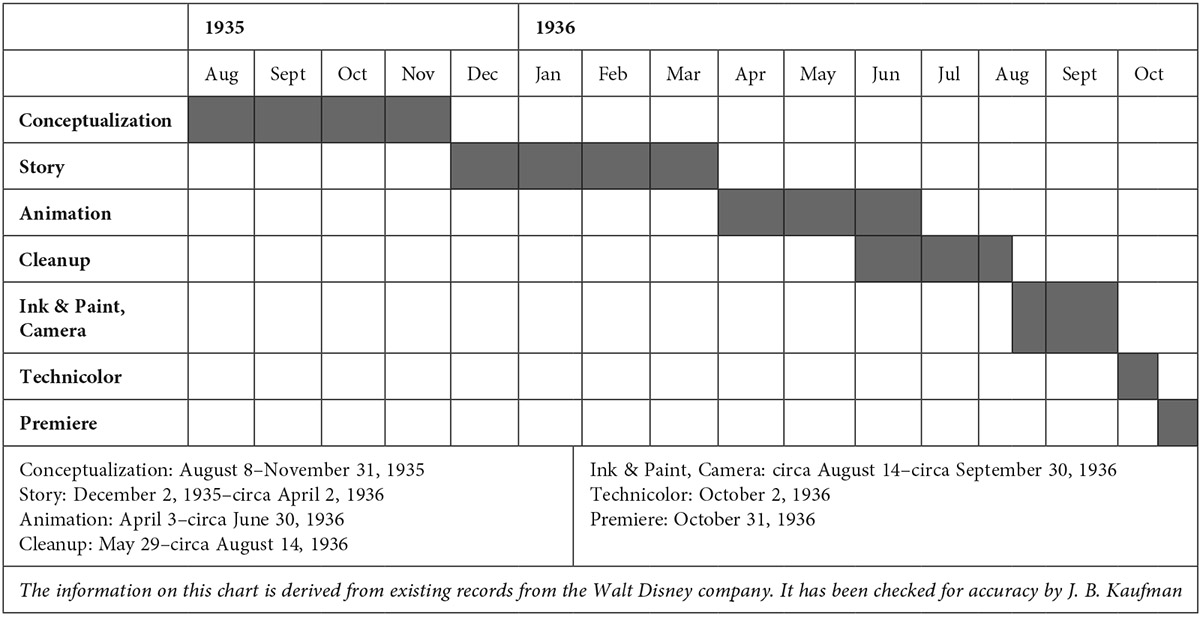

Production Schedule for The Country Cousin

Babbitt was kidding—she wasn’t blonde. But he wasn’t about to tell his boss he was dating Marjorie Belcher.

After The Country Cousin officially premiered on October 31, 1936, Babbitt received a memo. His work on it was graded “A1, 100%.” And just like with Moving Day, animators across Hollywood studied it frame by frame.14 Soon, The Country Cousin was called “the Studio’s tour de force. For mastery of animation, apart from technical ingenuity, a point was reached that has never been surpassed.”15 For Walt, the cartoon indicated to him that his animators could now tackle the seven dwarfs.16

For The Country Cousin alone, Babbitt received a bonus check for $1,201.00. He also put in his first request for a raise, from his $150 per week to $200 starting December 7.17 An additional clause in this new contract about the adjusted compensation for exemplary work suggested the bonus plan would complement his salary.18 But even in print, the criteria for these bonuses remained a mystery.

Still, that was a minor detail in a friendly, family-owned company like Disney. If there was any doubt to Walt’s affections, they were put to rest when he rented out the Barney Oldfield country club and hosted a staff-wide Christmas party.

Drinks flowed, and a live band played. Babbitt brought his movie camera with him and filmed his friends, including Marge. Walt sat at a table with his top men, laughing, smoking, and drinking. Babbitt put down his camera and found a cop who would go along with a prank. In a few minutes, an officer entered the country club and told Walt to keep it down, there were noise complaints. Walt laughed, pointed at the cop’s chest, and told him he would “have his badge.”19

It was a last hurrah before the Snow White crunch, and what followed was harrowing. Walt scrapped two complicated sequences that were already in production: an argument between the dwarfs, and a bed-building sequence. Precious time and money were spent on them, but the studio could not afford to finish the film unless these sequences were abandoned. Babbitt’s scenes remained intact.20

On January 4, 1937, the first completed animation was delivered to Ink & Paint.21 Each inker was expected to trace thirty cels per day and each painter to complete seventeen cels a day.22 The first completed cels were scheduled for Final Camera by March 13.23 In all, Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs required 250,000 drawings to be animated, inked on cels, painted, and photographed—all by December.24

While the Animation Department was crunching to accomplish this, the Story Department was in the clear. Obliviously, Pinto Colvig pushed his marching-band club. By February, Colvig had amassed an entire twenty-five-piece circus-style band of Disney employees, complete with uniforms. Colvig was eager for Walt’s endorsement and informed his boss that he was “trying to find an hour each week for practice when some of the members weren’t working or attending art classes.”25 Walt couldn’t believe that Colvig prioritized something so trivial when the fate of the studio hung in the balance.

Babbitt had been spending his off-hours with Marge. She observed the rules of propriety that governed her upbringing, including saving sex until marriage. Babbitt was patient and protective. He was prepared to settle down with her.26

His evenings were often spent at home, where he had his own animation desk and worked on his craft in his spare time. It was getting competitive at the studio. Now Babbitt was one of 32 Disney animators, along with 102 assistants and 107 inbetweeners.27 To fit all the artists needed to finish the film, the studio was constructing yet another animation building on the lot.

Woolie Reitherman, Frank Thomas, and the other art-school graduates had become full-fledged animators too. When Reitherman completed animating the Magic Mirror, he naturally picked up assignments for short cartoons. Around late February director Ben Sharpsteen assigned him to supervise the Goofy animation in the cartoon Hawaiian Holiday. For the first time, a major Goofy segment was assigned to someone other than Babbitt, who had already established Goofy as a slow hick. Reitherman, an active sportsman with a love of airplanes, contemplated how he would surf a wave if he were inside Goofy looking out. With his pencil to his animation paper, he began to draw.28

Meanwhile, Babbitt’s working style had come back to bite him. He had once again padded his scenes, this time a Dopey sequence in Snow White. On March 3, with less than ten months before the premiere, director Dave Hand was not about to tolerate Babbitt’s insubordination. He called a formal meeting to address it.

“Here is what I think—I am quite open with you,” Hand said to Babbitt. They sat in screening room Sweatbox 4, flanked by two sequence directors (likely with assistant director Hal Adelquist) and a secretary taking stenographic notes. “I think you are going off in your corner and taking it upon yourself to present something in the sweatbox which is entirely out of the line, or away, from what we as directors have tried to follow through—from the story conferences into the sweatbox . . . as if, say, you were superior to the three of us working together and agreeing on one way of handling it. . . . We spent a lot of time with you, which we should do. It is our duty to do it in order to get the scene right. We spared nothing. We acted it out, timed it with a stopwatch, [and] had you agree to what we were talking about before you left the room or we wouldn’t have let you leave. When you present it in the sweatbox, you have added footage without permission. You have not done the scene the way we say it.”

Babbitt retorted: “Do you want to see the scene the way we laid it out? I did it just that way.”

“Then it’s your duty to come up and tell us we’re not doing it right,” said Hand. “You have got to work with us, to give us the kind of stuff we want—and the kind of stuff we are trying to follow through from Walt’s angle. There is nothing personal in this. You have got to work with us or work by yourself. I can’t work with you this way!”

“In the first place,” said Babbitt, “you’re wrong in assuming anybody is trying to get off in a corner by himself. That is the way I’ve always worked. When I see a thing and I know it’s wrong, I take a stab at making it right. But in this instance, I tried to explain to you—I’m not making excuses—that these things weren’t satisfactory to me, but I had to get them in. . . .”

“If you needed more time,” said Hand, “you should have come up and gotten it, not misinterpreted the scene. It occurs in other scenes, too.”

“I’ll go up and get the exposure sheets and the test we did!” said Babbitt.

“We want to do that,” said Hand, “but that has nothing to do with the point we’re making. I’ve worked with a group of animators and directors and I see a condition that needs to be remedied. It’s a bad condition, with one animator. Whose fault it is, we’ll find out. But we must correct that condition. That’s my point. I bring it up directly to the animator in order to work out the differences and clear it up so you can be productive.”

Babbitt responded, “Don’t get the misunderstanding that anybody is working against you. The blame lies right with myself. I would like to say it wasn’t my work, but it so happens that is the result gotten. I have done a lousy job and wanted to fix it.”

Hand pointed out another of Babbitt’s scenes in which he extended footage—when Snow White first terrifies Dopey. “I remember saying to you that the directness and shortness of speed of the scene were what made the comedy,” said Hand. “I heard the same words repeated by Walt this morning—exactly what I told you. When I hear Walt speaking the words that we have spoken, well, a mistake is being made and I don’t like it for the sake of the picture.”

“I have the test and I will show it to you,” Babbitt rebutted. “I animated it exactly in the time allotted.”

“We went over it eight or ten times with a stopwatch and put it on the sheets!” said Hand. “I say directly that you didn’t animate it properly. And that’s my argument here. You are wasting time that we need badly to finish the picture.”

Babbitt tried to interrupt with what he thought about it, but Hand jumped in.

“I don’t care what you think,” continued Hand. “I could go to Walt and say, ‘That’s just no good, get him off the picture!’ My object is to line you up so you can move the stuff through—to help you so you can move it through properly. I like to allow an animator freedom on a scene, but now we find you’re making mistakes in your direction. You mustn’t go off into a corner. You mustn’t use some of your ideas without talking them over with us. We’ll drop it now,” Hand concluded. “Anything we can do from our end of it—to help you or change our ways of working with you—we want to do it. And we’ll be glad to do it. Think it over and come back and tell us what we can do to help you.”

“Well,” said Babbitt, “you might animate it for me!”29

That evening, Babbitt donned his finest eveningwear as Walt’s guest to the Academy Awards ceremony in the Biltmore Hotel banquet hall.30 Walt accepted the award for The Country Cousin. Babbitt, meanwhile, filmed the Hollywood glamour with his movie camera, pointing it at stars like Frank Capra, Jack Warner, W. C. Fields, and Cecil B. DeMille.

That night, he drove his car back to his new house, a home on Hill Oak Drive overlooking Hollywood.31 This house had a large dining room, a sizeable kitchen, and a living room with a fireplace and a baby grand piano. It was not the house of a playboy but of a committed sophisticate ready for the next step with Marge.

As their courtship blossomed, Babbitt shared his world with Marge. They went camping and skiing. They and the Adelquists went to the beaches of Santa Barbara. He took her to Red Rock Canyon to shoot skeet. He and Marge hosted brunch with their friends. It was a life and a love that excited them both.

In June, Walt Disney cut out another finished scene from Snow White, one with the dwarfs eating soup. For the sequence’s animator, Ward Kimball, it was a punch in the gut.

But Walt’s bank loans were drying up. The studio could not afford to produce the film with this sequence. From the initial proposed running time to this final cut, the animation in Snow White dropped from ninety-one minutes to seventy-eight.32

As the film neared completion, sections were screened in-house. Because of his perfectionism, Babbitt felt his animation of the Queen was riddled with flaws.33 Others saw it as exemplary, recognizing the “depths of passion” that he bestowed on her.34

His own passion came to fruition on August 8. With a princely $886 bonus check for Mickey’s Amateurs cushioning his bank account, Art Babbitt and Marjorie Belcher were wed in Santa Barbara. Hal Adelquist was one of the groomsmen.35 (Two days later when Marge performed a ballet at the Redlands Bowl, rice and not flowers was thrown at her feet—to the bafflement of the general audience.)36

Babbitt’s Goofy animation was the highlight of Mickey’s Amateurs, and it holds up as an exceptional one-man comic ballet. Nonetheless, Walt was unhappy with the story that Pinto Colvig assembled. It did not give the characters’ personalities room to shine—and it made Donald Duck a tommy-gun-wielding psychopath. In mid-August, Colvig wrote Walt a letter asking for a raise.

A frame of a home movie with Art and Marge Babbitt with the Adelquists on vacation. Hal Adelquist sits nearest to camera.

In Walt’s words to Roy, “This crying attitude expressed in Pinto’s letter is typical of him. He is very unreliable, and I do not need his voice for the Goof badly enough to tolerate him any longer. I am not going to renew his contract.”37

Soon, Pinto Colvig was gone from the Disney studio lot.38