15 Defense Against the Enemy

NEW YEAR’S DAY 1937 was approaching in Flint, Michigan, home to the largest automobile plant in the world. The city manufactured more than two million cars a year for General Motors, using enormous machine rooms that ran day and night. On the evening of December 30, 1936, thousands of workers walked into three Flint auto factories, carrying bags of food and clothing. They locked the doors from the inside, pulled the main switch, and stopped production. They held a sit-down indoors and refused to budge.

Auto plant workers were tired of suffering arduous work in concrete rooms that were either freezing or sweltering, depending on the weather, surrounded by thunderous machines. There was no paid overtime or job security. Trying to negotiate for better terms was a losing battle: a member of lower management would bargain on behalf of the workers to upper management. This “union leader” might claim he had the workers’ best interests at heart when actually looking after the interests of the company. The General Motors workers demanded the right to be represented by the union of their choice—not by an in-house company union but by an independent, industry-wide union. They wanted the right to join the United Auto Workers.

From the windows of all three Flint factories, workers hooted and hollered. They waved protest signs and dangled effigies. Outside they were monitored by factory police, cheering supporters, and the press. Workers at General Motors plants in five other cities went on strike in sympathy. Supporters drove in to picket around the buildings and to shield them from factory police. By January 4, the sit-down had become a national headline.

General Motors refused to negotiate. They filed seeking a court injunction to force the strikers to leave, but the United Auto Workers discovered that the ruling judge owned shares of General Motors stock. The union sent its list of demands: union recognition, rates per day instead of per unit (called a “piecework system”), grievance procedures, reinstatement of all those who had been fired for union activity, and a thirty-hour workweek. GM retaliated by shutting off the heat in the building. The sit-downers bundled up with the added layers their supporters and families pushed through the first-floor windows.

On the night of January 11, the factory policemen arrived wearing riot gear, bearing guns and tear gas. Those inside retaliated by making slingshots from inner tubes, flinging 1½-pound car door hinges. The fight lasted until dawn. Fourteen workers were injured by gunfire, and some were carried out in stretchers, but the sit-down continued.

As GM enlisted more militia, newsreels projected images of gas bombs and gun-wielding police. Never before had such a large corporation been shut down by its employees. The governor of Michigan requested a peaceful solution. President Roosevelt urged GM to accept the workers’ terms.

Finally, on February 11, General Motors signed a one-page contract with the United Auto Workers union, affiliated under the Committee for Industrial Organization (CIO), granting employees the right to choose their union representation. The contract permitted union talk on employee downtime, and there would be no discrimination against union members. The victorious sit-downers marched outside to cheering crowds waving enormous American flags.

On the evening of March 9, 1937, President Roosevelt addressed the nation in one of his fireside chat radio broadcasts. After years of combating the unmoving Nine Old Men of the Supreme Court, the president described his plan to retire every judge over the age of seventy, as was customary in the military and civil service. Those who refused would receive a younger assistant with equal voting power. Detractors criticized Roosevelt for trying to “pack the court” with his own appointees, but by April the proposal was moot. The two swing-vote justices joined the three liberal judges. When the National Labor Relations Act was challenged, the Supreme Court ruled on April 12 to uphold it. American unions would be strengthened again.1

Immediately after the ruling, some Hollywood labor leaders revived a dormant group of unions called the Federation of Motion Picture Crafts (FMPC). The FMPC had about sixteen thousand members. Most of them came from two large unions: the International Brotherhood of Painters, Decorators & Paperhangers Local 644, known colloquially as the Painters Union (which included set painters, scenic artists, makeup artists, and hairstylists), and the Studio Utility Employees Union (which covered roles such as carpenters, plumbers, boilermakers, and machinists).2

However, if the FMPC was to thrive, it would have to simultaneously battle both the studio producers and its rival, the Bioff-held IATSE.

Hollywood producers were still participating in Bioff’s schemes. In 1937 RKO and Loew’s saved $3 million in labor costs by paying the IATSE $100,000—their share of the $500,000 kickback that all the studios had agreed to cough up.3 On top of that, Bioff and Browne were totaling $1.5 million on the “2% assessment” garnished from members’ wages.

On April 30, 1937, the Painters Union and the Studio Utilities Employees Union went on strike, demanding union recognition and higher wages. One picket captain and Painters Union member was a tall, forty-year-old ex-boxer named Herbert K. Sorrell. He refused to be intimidated by the IATSE. First the IATSE bribed the strikers with free membership if they returned to work. Then the IATSE carpenters walked through their picket line. Within days, goons from Chicago arrived and began pushing nonstriking cinematographers across the picket lines. The IATSE enrolled the Teamsters Union to drive trucks of actors and technicians past the strikers, who retaliated by shoving the vehicles and shouting epithets. The Teamsters brought more goons from Los Angeles, so Sorrell brought in local longshoremen and industrial laborers. Physical altercations turned bloody, and violence spread from the picket line to the local IATSE office, where ex-strikers were pummeled.4

On May 21, the FMPC’s Studio Utilities Employees caved. The IATSE arranged to get them an 11 percent pay raise to break the strike. The FMPC Painters now stood alone on the picket line. As they held their ground, painter unions around the country picketed in sympathy and spread boycotts. In early June, IATSE offered the Painters Union a 10 percent raise and closed-shop status if members returned to work and signed with them. The strikers voted unanimously against.5

Finally, on June 14, the studios surrendered and signed with the FMPC Painters. Its members earned a contract and a 15 percent salary increase and became the first local union to be granted closed-shop status. There were resounding cheers of victory. It had been Hollywood’s largest labor strike up to that time, and this monumental win left a lasting impression on filmmakers and animators alike.6

Bioff, however, considered it a missed opportunity. Perhaps the few crafts under IATSE jurisdiction—the stagehands and projectionists—were too limited. He began formulating a plan to expand his enterprise.

During that same time in New York City, nearly a hundred animation artists at the Fleischer Studios went on strike. The men and women who drew Popeye and Betty Boop filled Broadway with illustrated signs demanding higher pay and union recognition. It was the first strike at an animation studio and lasted from May 7 through October 12. In the end, the seventy-five strikers won a union contract. They returned to work with wage increases, a forty-hour workweek, paid vacation, sick leave, overtime pay, and a bargaining agent to represent them.7

The ripples of the successful Fleischer strike reached Hollywood, where the Warner Bros. animators drew Porky Pig and a daffy, darn-fool duck. They signed up with a new independent union in Hollywood that had formed that fall. Called the Screen Cartoon Guild, it was run by animators and attested to be “the only bona fide organization representing all of the studios in the Animated Cartoon Industry.”8

By September Roy Disney was at the end of his rope. Even with the additional loans, the studio had gone way over budget on Snow White. Roy lamented to Walt that there was no choice but to ask the Bank of America for an additional $327,000.9 They’d both meet a representative at the studio, he said, and together make their request as they presented a scrappy, work-in-progress reel of Snow White.

Walt would recount the event years later with a storyteller’s flair: at the designated time, Roy wasn’t there. Walt sat in the studio projection room with young banker Joe Rosenberg and screened the unfinished reel. When it was over, Walt walked Rosenberg to his car, unsure if the loan was secured. Once in his car, Rosenberg turned to Walt one final time, told him the film was going to make a heck of a lot of money, and drove off.

Walt stood there alone, sighing with relief.10

Walt had big plans if Snow White turned out to be a success. The Story Department had already started preproduction work on two more animated features: Bambi and Pinocchio. There was also talk of animating a Mickey Mouse cartoon to Paul Dukas’s music of “The Sorcerer’s Apprentice.” But these ideas meant nothing if Snow White failed. To hundreds of the artists, their jobs rested on this gamble. “There would be all kinds of opportunity if Snow White was a success,” remembered one artist, who added, “I’m sure those voices of doom haunted the people working with a frenzy to complete Snow White in time for the grand première before Christmas.”11

Snow White was still far from complete. On October 15 the staff learned that their 8:30 AM–5:30 PM weekday work hours now extended from 7:30 AM to 6 PM, with no paid overtime.12 It was no secret that Walt promised his workers reimbursement bonuses after the film recouped its cost. Soon the artists were extending their Saturday hours for no pay, and many worked Sundays as well.13

In the weeks before its premiere, the Disney artists were working “night and day.”14 One frazzled artist painted a watercolor sketch transforming the dwarfs’ bedroom into a torture chamber, with an exhausted animator sprawled in a corner and Walt, in his pajamas, praying on his knees with his hands clasped, “Please God, send me an animator who can work twenty-four hours a day.”15 In the studio hung the air of a collective nervous breakdown. A sign outside the writers’ room said, IT WAS FUNNY WHEN IT LEFT HERE.16 For a week, stressed animators swapped doodles of the characters in a full-blown orgy.17

Finally, on November 11, the animation for the film was complete. The inkers, painters, and camera operators raced against the December 1 deadline.18 It would then take more than two weeks to process and distribute the film before its December 21 premiere.

It happened one morning in early December 1937. Art Babbitt was walking through the studio when suddenly he was buttonholed by Dave Hilberman, Bill Tytla’s assistant. Hilberman had started at the studio in July during the influx of new talent. Knowing Babbitt’s reputation for being staunchly principled, Hilberman showed him a page from Time magazine.

The article concerned mobster Willie Bioff and the IATSE. Apparently, Bioff—described as a South Side gunman and bodyguard for George Browne—was seeking to enroll all Hollywood crafts. Bioff blamed industry corruption on Communist interference, calling his detractors Communists too. The representative from the Carpenters Union (which succumbed to the IATSE during the FMPC strike) warned the public: “You’ve no more chance of doing any good in this situation than a snowball in hell.”19

Babbitt took the magazine and headed toward management. He found the production control manager and head of the camera department, Bill Garity, who told Babbitt that an IATSE group had already visited the studio. He suggested Babbitt “cook up something” to enroll Disney employees before the IATSE did.20

With that, Babbitt went to Roy Disney, who pointed Babbitt next door to the office of Gunther Lessing, the company’s chief legal counsel and the senior vice president. Lessing read the article, listened to Babbitt, and suggested a nonofficial, social organization. He offered Babbitt his professional services, as well as the studio’s space and resources. Lessing also handed Babbitt a book about unions, designating a couple of chapters for him to read.

“I knew nothing about unions and really stepped into this,” Babbitt said in 1942. He read the book cover to cover.21

Later that week Babbitt sat at his desk and listed thirty-five artists across the studio to invite to his first committee meeting. He took the list to a music room secretary to be typed, and she handed it off to the Copy Department that day. When the Copy Department returned it to her through interoffice mail, she called the Traffic Department, and an errand boy delivered a copy to each name in the memo. It read, “A very important meeting affecting everyone listed is to be held in Sweatbox #4 at 4:30 today, Friday. Please be present and don’t worry.”22

By phone, Babbitt also invited Gunther Lessing.

That afternoon, thirty-five employees from every department sat in the projection room, including Hal Adelquist and supervising animators like Norm Ferguson, Fred Moore, Woolie Reitherman, and Frank Thomas. Babbitt stood up front, elucidating the Time article and the impending threat of Bioff and Browne.

Then Lessing took the floor. He warned that a “solid, compact group” would make them prey to an outside union; rather, if they remained loosely knit “along social lines,”23 they could act quickly against any IATSE attempts. The majority of attendees voted in favor of starting this social organization, and they unanimously appointed Babbitt as its chairman.

There were other reasons to keep this merely a loosely knit social organization. Unions had a bad rap among conservatives. One was national columnist Westbrook Pegler, who called President Roosevelt’s government corrupt, saying unions were linked to either Communism or organized crime. In a country that voted for a Democratic president by a landslide, Pegler’s right-wing diatribes were read by nearly six million Americans, six days a week.24

The next morning, Babbitt drafted another memo on an interoffice slip and distributed it to all studio personnel that afternoon. It heralded the new social organization at the studio comprising representatives from every creative branch. The memo concluded, “It was decided that a 100% membership in this organization was imperative to enable it to most fully benefit everyone in this studio. You’ll probably be pleased with the plan.” Babbitt signed it “Chairman.”25

Within the next ten days, Babbitt led five more meetings across all departments throughout the studio. Up to fifty people attended each group meeting, and Gunther Lessing accompanied Babbitt to nearly every one. Each of the five groups elected two or three representatives, which formed an executive board.

The organization needed a name, but that would come later. First, there were other pressing matters. The very first feature-length animated cartoon was about to premiere.26

On the evening of Tuesday, December 21, one car after another pulled up to the Carthay Circle Theatre in Hollywood. A frenzied mob of thirty thousand people crowded to bear witness. Flashbulbs burst, and newsreel cameras whirred. Costumed Disney characters greeted the public. Stars like Ginger Rogers, Cary Grant, Charlie Chaplin, and Shirley Temple walked the red carpet. Finally, Walt and Lillian Disney stepped out of their car, dressed like Hollywood royalty, greeted by a roar from the crowd.

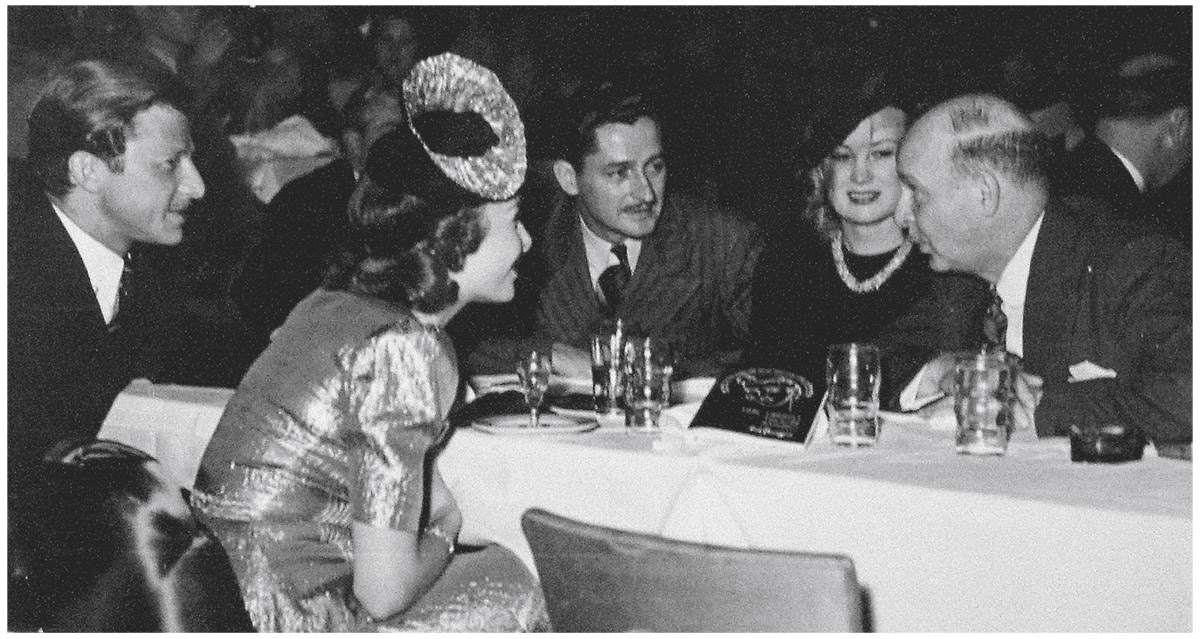

Art Babbitt, Marge, the Clarks, and Gunther Lessing.

One of Babbitt’s house staff drove him and Marge up to the red carpet. Walt had given everyone who worked on the film a ticket to the event. The public craned their necks to catch a glimpse of a star. When the animators arrived, there were audible grumbles of disappointment. “Aaaah, that’s nobody!”27

Ushers handed out programs. The Disney employees found their seats in the back of the theater. Then the lights slowly dimmed, and the crowd grew silent. The theater’s enormous red curtain rose to the rafters, uncovering the huge dark screen. A beam of projected light pierced the darkness. The words A WALT DISNEY FEATURE PRODUCTION lit up the screen with the swelling of the soundtrack’s orchestration.

After long hours, mounting debt, and cries of “Disney’s folly,” the loyalty of his employees was Walt’s most precious resource. Following the title card, a message from Walt appeared on screen: MY SINCERE APPRECIATION TO THE MEMBERS OF MY STAFF WHOSE LOYALTY AND CREATIVE ENDEAVOR MADE POSSIBLE THIS PRODUCTION.28

And there, in front of Hollywood’s elite, were the first Disney screen credits the public had ever seen following a title card. Listed were Walt Disney’s creative supervisors, story adapters, designers, background artists, and finally, animators. For the first moment in his life, Babbitt saw his own name emblazoned on a film. This was finally proof of his contribution to the art form that meant so much to him. There it would remain, for all time, across nations and generations—evidence that Arthur Babbitt had animated on Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs.

Replica of a flowchart of the Disney studio, from a 1943 employee handbook. A handful of the items are particular to that year, but most are consistent with the workflow in the late 1930s.