2 Poor and Starving

When he returned to Kansas City in late 1919, Walt moved back into the Disney family home, now occupied by Roy, Herb, and Herb’s wife and daughter.1 At first, Walt dreamed of becoming a newspaper cartoonist at the Kansas City Star. As movie studios now started opening, newspaper cartoons became a wellspring of source material for moving pictures. Walt had been fourteen years old when many popular comic strips made the leap to film: Mutt and Jeff, Krazy Kat, and The Katzenjammer Kids had all premiered on-screen by 1916. Cartoonist Winsor McCay had already broken ground with his original, personality-driven film Gertie the Dinosaur in 1914.

Like the newspaper comic strips that begat them, too many animated cartoons starred simple characters with basic designs. Each scene resembled a square panel from a comic strip: characters were seen head to toe, moving between left and right. Emotion was shown with exaggerated stock expressions interchangeable for all characters. Sometimes symbols appeared over the characters’ heads, a reminder that these were moving comic-strip cartoons and not screen actors.

Animated cartoons had already become mainstream during Walt’s adolescence. In 1914 John R. Bray’s New York–based studio (the first studio built for animation) released its Colonel Heeza Liar cartoons followed by the Bobby Bumps series. Then Bray’s production manager, Max Fleischer, began a series of his own called Out of the Inkwell starring his cartoon character Koko the Clown. Koko was rotoscoped—drawn by tracing live-action footage—and thus had human movement and proportions. The series wowed audiences.

Walt did not get a job at the Star. However, he secured an illustration job at a small commercial art studio drawing advertisements for farm magazines.2 Besides pictures of happy cows and enthusiastic chickens,3 he also illustrated programs for the town’s grand new cinema, the Newman Theater.4

Soon a new employee showed up—like Walt, he was tall, lean, and eighteen years old. His name was Ubbe Iwwerks, and he could out-draw just about anyone. Iwwerks noticed that during breaks from work, when the other young guys were playing cards, Walt sat alone at his drawing board, practicing his signature.5

After the Christmas rush, Walt and his colleagues were laid off, and Walt spent his free time drawing. As January 1920 dawned, Walt drew a political cartoon of Baby New Year oblivious to the travails ahead. Bursting through the doorjambs and windows of a house labeled THE WORLD were the words TURMOIL, STRIKES, REDS, COAL STRIKE, RAIL STRIKE, ANARCHY, and I.W.W., along with a man wielding a bomb.6

It was then that Walt dreamed up his first capitalist venture. He fought Elias for his own savings to use as capital (Elias eventually sent him half) and, with Iwwerks, opened a commercial arts house named after the two of them.

Their business never got off the ground, and by March7 both quit the endeavor to work as commercial artists for a businessman named A. Vern Cauger. Cauger’s operation, the Kansas City Film Ad Company,8 made motion picture advertisements for theaters. Walt’s job was to draw figures on paper, cut them out, and move them under a downward-facing camera, one frame at a time. Twenty-four frames made one second of screen time. (Though uncommon now, cutout animation was prevalent across the globe in the early 1900s.) Walt began experimenting with Cauger’s camera equipment in his spare time and developed aspirations to make his own films.9

In the spring of 1920, Elias, Flora, and Ruth returned to Kansas City. O-Zell was bankrupt. Elias used his carpentry skills to build a garage adjacent to the family house to rent out. When the garage was complete, Walt convinced his father to rent it to him for five dollars a month as a studio, and Elias agreed.10 According to Roy, Elias never collected.11

Only a few months later, Roy collapsed in the middle of the street. He was diagnosed with tuberculosis, contracted while in the navy, and he was transferred to Tucson, Arizona, to recuperate.

Roy had been Walt’s emotional rock and strongest ally. With Roy at death’s door, Walt tackled his next goal with unfounded brazenness. Using his new, ad-hoc studio space, Cauger’s borrowed camera, and the experience he gained at Film Ad, Walt conceived of some shorts to play in a local cinema. In addition to animating paper cutouts, he glued cutouts onto transparent sheets of celluloid that he could shoot over a painted background. In the garage, day after day, he drew, inked, and photographed well into the night.12 After a month’s time, he had completed some short animated clips he called Laugh-O-Grams, depicting commentary on Kansas City life and intended to play before a feature film.

Several movie theaters had sprung up in Kansas City, but the biggest and most palatial was the Newman Theater. If Walt was going to strike a deal with a theater, it was Newman’s or nothing. Filled with moxie, he filmed the name of his little production, “Newman’s Laugh-O-Grams,” and spliced it in at the head and tail of his reel.

Walt made a date to meet with the theater manager, screened his reel, and landed a contract. Walt’s audacity genuinely impressed Elias, and he would later say of his son, “He has the courage of his convictions.”13

Walt didn’t quit his day job at Film Ad, though the local notoriety may have gone to his head. One day at work, the company bookkeeper arranged a meeting with him. Walt had not been punching in and out on the company time clock. He argued that the punch card ritual was inane. A truly inspiring workplace, he felt, wouldn’t need to monitor its employees with time clocks. The bookkeeper warned that ignoring company regulations had a bad moral effect on the other employees. “I told him that if I punched it, it would have a bad moral effect on me,” remembered Walt. Finally Walt acquiesced, but the bookkeeper’s satisfaction was short-lived. The next day, Walt started punching all the spaces of his card at the same time.14

Working for the product, and not for the paycheck, was Walt’s ethos, and it would stay with him for the rest of his life.

That summer, Herb, his nuclear family, Elias, Flora, and Ruth all moved to Portland, Oregon. In November 1921 Elias and Flora sold the family home in Kansas City.15 Walt, however, stayed behind. He would have to figure out his next move on his own.

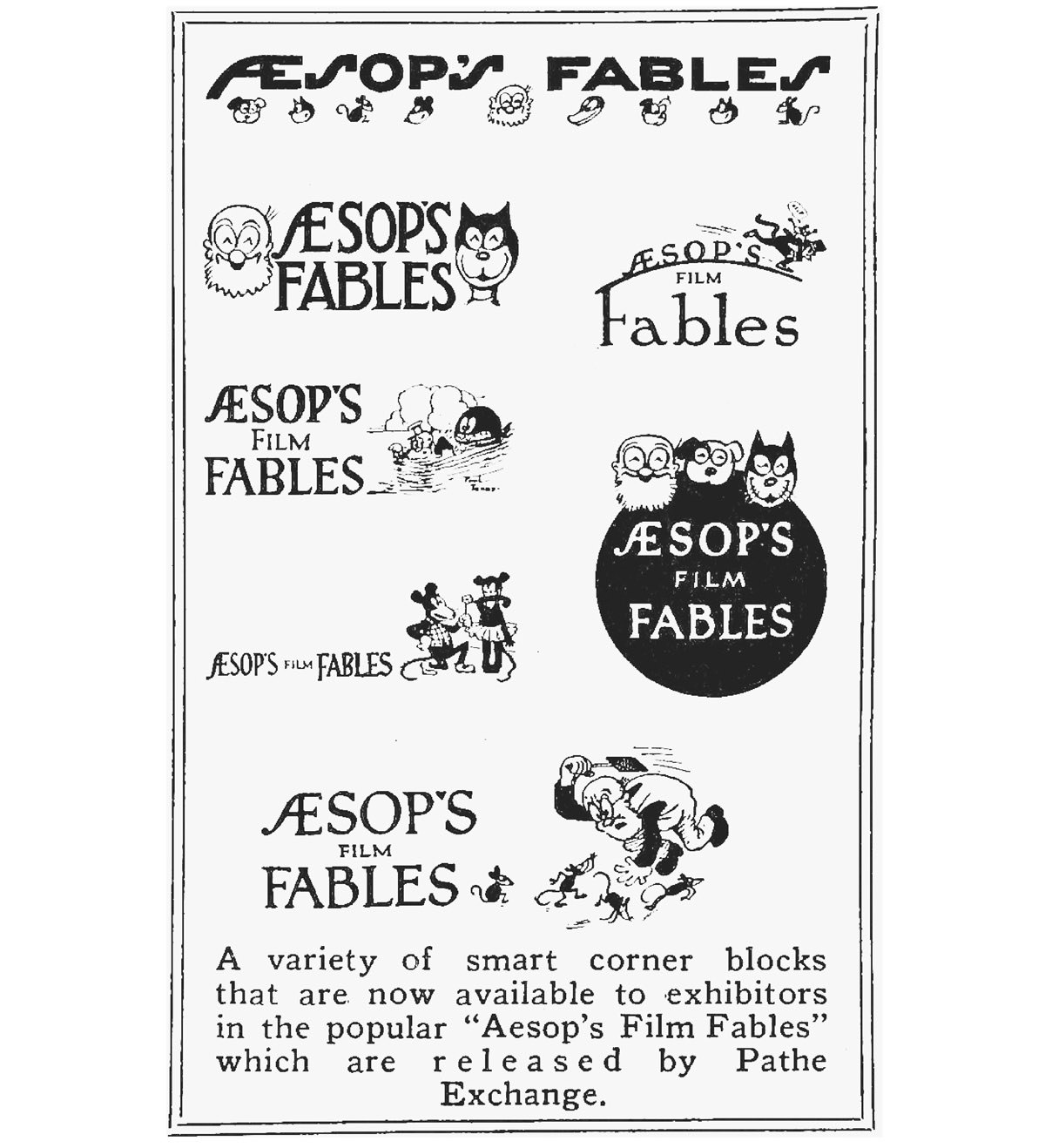

In the chill of December 1921, from a cheap apartment, Walt reflected upon the animation art form. Over just a couple years, he had watched the global popularity of animated cartoons skyrocket. Felix the Cat had become the first recurring star of animation. Paul Terry directed animal-themed cartoons, called Aesop’s Film Fables, for a company he formed with Amadee Van Beuren called Fables Pictures. Walt watched these films with admiration.16

A 1926 exhibitor’s magazine ad for the cartoons directed by Paul Terry that inspired Walt Disney.

Though ambitious, Walt’s desire to penetrate the animated cartoon industry was not that bizarre. What was unique was his youth as a studio head. It made an impression on other local young men who worked in animation, including young animator Isadore Freleng and young cinema organist Carl Stalling. Walt would eventually hire them both (though they would eventually make their mark at Warner Bros. animation).

In the spring Walt quit his job at Kansas City Film Ad, and on May 18, 1922, he incorporated Laugh-O-Gram Films. Walt enthusiastically hired a handful of peers from Kansas City Film Ad, including Iwwerks and his friends Rudy Ising and Hugh Harman. The company moved to an office building17 and began a series of fairy-tale-themed cartoons.

The Laugh-O-Gram team operated not hierarchically but collaboratively. Story premises were discussed as a group.18 They also drew in ink directly on the sheets of clear celluloid, or cels. The interiors of the inked lines were opaqued with white, gray, and black paint.19 Then they were photographed under an animation camera, over the painted background, cranking one frame at a time.

They were a guerrilla animation crew, underdogs in the industry, and they delighted in it. They drove around town promoting the Laugh-O-Gram company or rode in the Main Street parade with big Laugh-O-Gram signs.20 Come success or failure, they were in it together.

Over the course of the year, the little studio produced seven fairy tale films. These cartoons were made for screening at local schools, clubs, and church benefits.21

Over time there were stops and starts with hopes for broader distribution, but the crew had enough work to keep Laugh-O-Gram afloat. Inspired by the Out of the Inkwell shorts, Walt decided to make a new film—a live-action little girl in a cartoon world, calling it Alice’s Wonderland. This film, Walt hoped, could be their ticket to commercial success.

Laugh-O-Gram Films spent several months producing Alice’s Wonderland, filming the child actress Virginia Davis and animating her cartoon backdrop, while Walt borrowed money against the company. In May 1922 he sought out a distributor, and he found one in Margaret Winkler.

Winkler was only twenty-eight years old but was already a name in the industry. In New York she had become the distributor of Out of the Inkwell and various Felix the Cat shorts. Eager for another hit series, Winkler wrote back with interest in seeing the Alice reel.

Walt, however, couldn’t send it; it was an asset that belonged to one of his creditors. He stalled and kept up a written correspondence with Winkler, apologizing for setbacks. Winkler grew increasingly impatient.22

By that summer of 1923 Walt was slipping ever deeper in debt and had to lay off his staff. He began skipping meals and soon noticed that his clothes were fitting a lot more loosely. Roy forwarded Walt some of his government checks, but these weren’t enough. Walt’s rent was overdue, his assets were repossessed, he started scavenging for his food, and he was evicted from his apartment. Eventually he was sleeping on rolls of canvas in the Laugh-O-Gram office.

He received mail from Roy and Uncle Robert, both of whom were now living in Los Angeles, California, urging him to join them. Los Angeles was quickly becoming the center of the country’s motion picture industry. Universal Pictures (formerly Universal Film Manufacturing Company), Fox Film Corporation, and Paramount Pictures had established studios there by 1915. United Artists (co-owned by Walt’s comedy hero Charlie Chaplin) was built in 1919.

If it was good enough for Chaplin, it was good enough for Walt. He headed for Los Angeles that August with $40 in his pocket and $300 of debt behind him.23

Once in California, Walt finally sent Margaret Winkler a print of Alice’s Wonderland, and she offered him a generous contract for $1,500 per film. That was all Walt needed to incorporate the Disney Brothers Cartoon Studio. By June 1924 the studio was a small but well-oiled company on Kingswell Avenue. Walt was producer, and Roy was business manager. All his Kansas City colleagues had moved to Los Angeles to join. The future looked bright.