4 Arthur Babbitt: Hell-Raiser

Mr. and Mrs. Babitzky lived in a small house on the poor side of Omaha, Nebraska, in 1907. They were Jewish immigrants, having emigrated to America from Petrokov, a Polish city dominated by the Russian Empire. Solomon (sometimes written as “Shloime” or “Samuel” on public records), a lean man with thick glasses and a walrus mustache, was an ardent Jewish scholar with few profitable skills. He took a steamship alone to America in 1903. Zelda witnessed the Russian Revolution of 1905, a social and political upheaval dominated by labor strikes and successful in its goals of creating a multiparty system and a brand-new constitution. In 1906 she emigrated with their three-year-old daughter, but the child grew ill on the ship and died before arriving.1 According to family lore, she was the second child the couple had lost.

Arthur Harold Babitzky was born on October 8, 1907, in Omaha. He was the first Babitzky child to survive. A year later another daughter was born, but she succumbed to illness at the age of two. Arthur remembered being three years old and finding his mother in her bedroom, weeping and holding the child. He wrote years later, “This was my first encounter with the injustice that oftime befalls an innocent.”2

Soon two brothers were born—Irving in 1911, and William in 1913. They, too, would survive, but health problems threatened the Babitzky children. The fontanel, an opening in Irving’s skull, was slow to close. Ever devout, Solomon begged God for mercy, going so far as to place his own head inside the synagogue’s holy ark that the Lord may take him instead. Arthur remembered having a health condition that required Zelda to give him alcohol sponge baths before putting him to bed.3 His mother’s love and pragmatism would forever cleave him to her. Conversely, he would scoff that his father was “ever an optimist—for he placed his trust unhesitatingly with an all-knowing ubiquitous God who would some day accept in trade suffering and misery as a down payment on happiness and justice.”4

While Solomon peddled rags or fish door-to-door,5 Zelda made embroidery for sale and handled the cooking and child-rearing at home. There were more than just her own offspring; she made her home a safe house for needy neighborhood children. She had a potent sense of justice; when Arthur behaved poorly, she invited a police officer to the house to scare some sense into him. “Zelda really was a firebrand,” recalled her eldest grandchild, Susan Fine. “Her life was made up in defending the rights of others. My grandmother was very strong-willed; if she had it in for you, God help you.”6

To Solomon’s credit, he fostered a taste for classical music in the family, and his own violin playing sometimes filled the small house. He also provided little Arthur the key ingredient for a future animator in that era: discarded newspaper comics.7

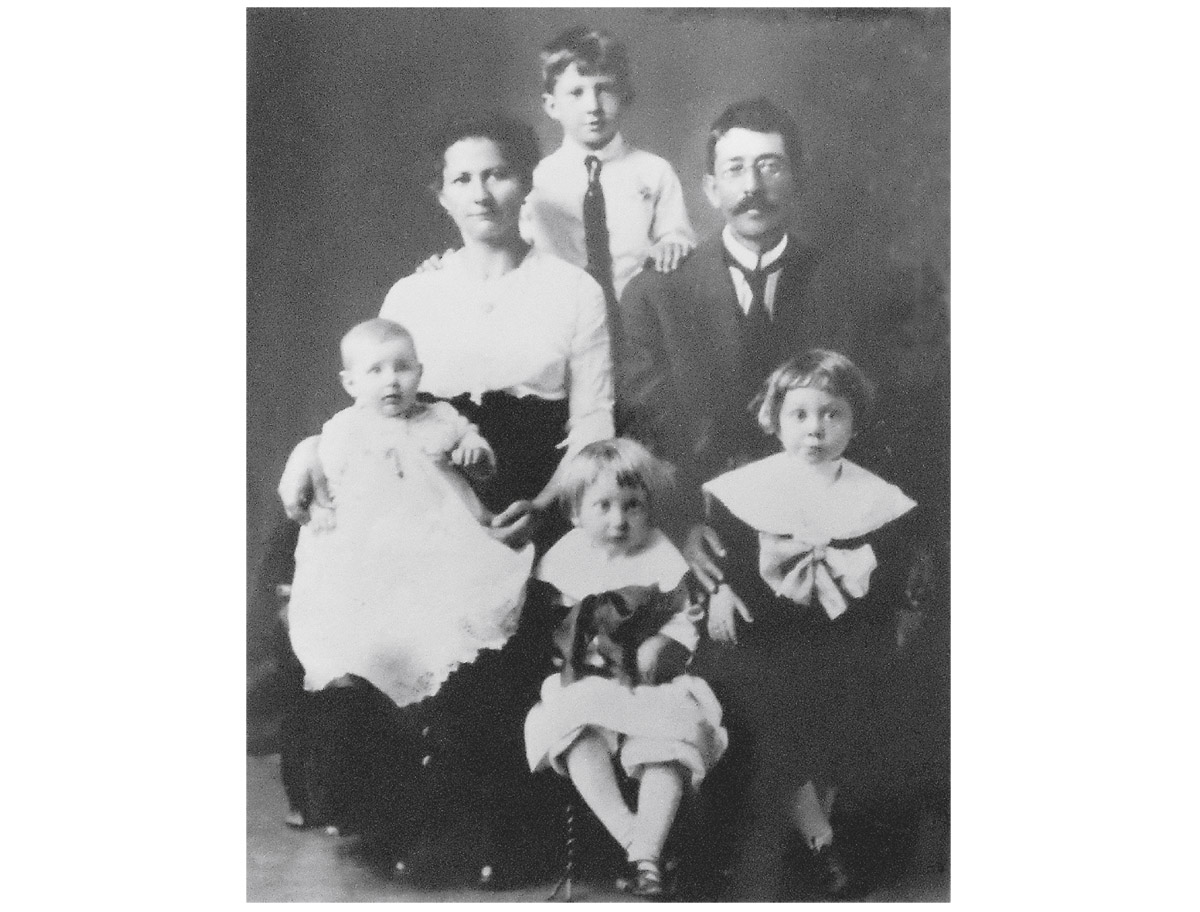

Family portrait of the Babitzkys, 1915. Arthur is top center.

Arthur was completing kindergarten when Omaha was ravaged by the worst tornado outbreak the Midwest had ever seen. It struck on the evening of Easter Sunday, March 23, 1914, which also fell on the Jewish holiday of Purim. The city had no siren warning system, and most homes had no telephone or radio; a few bystanders saw multiple oncoming tornados from a distance as the winds raced toward them at record speeds. Citizens bolted through the streets, hollering the warning to their neighbors.

Within minutes, four colossal tornadoes engulfed Omaha, tearing through the Babitzkys’ neighborhood. Houses were ripped to shreds. Women screamed as babies were sucked through windows. Entire carriages and massive stone plinths soared through the sky, and chunks of homes came crashing down into the street. The ceiling of a bakery crushed a family of seven. A pool hall collapsed, killing everyone who had sought refuge inside.

When the tornados had run their course, they left a path of destruction seven miles long and a quarter mile wide. More than one hundred people were dead or missing. Hundreds more were homeless. Arthur’s home was spared by a margin of four blocks.8 The mayor, in his hubris, refused federal aid.

The Babitzkys had had enough of Omaha. Solomon and Zelda decided to relocate ninety-six miles north to Sioux City, Iowa.

Around that time, Sioux City was heralded as “the metropolis of the northwest where the farmer, the rancher and the captain of industry join hands.”9 In February 1915, with Zelda pregnant, the Babitzkys made the trip by horse and wagon with all their household possessions.10 The strain of Iowa’s harsh winter caused Zelda’s baby to be born prematurely but healthy—a daughter that they named Frances.

The Babitzkys’ house was located in a dense concentration of Jewish, immigrant, and Black families, “formerly homes of non-Jewish people who had improved their lot economically, and moved up to better houses,” remembered Irving.11 Although Sioux City had its share of anti-Semitism, from name-calling12 to KKK marches,13 the Babitzkys lived safely, within walking distance of the local synagogue and near three kosher butcher shops. Meatpacking was one of the cornerstones of the economy, and the smell of slaughterhouses was inescapable.14

Their rented house included a barn for the family’s horse, and during the colder months, Solomon used horse manure to insulate the side of their house. For fun, Arthur and Irving leapt from the barn’s rafters into hay piles.15 The end of winter brought the blossoming of Zelda’s vegetable and herb garden, and each of the children was given a small bed of soil in which to grow radishes, lettuce, scallions, and dill. Jars of homemade pickles lined the walls of the storm cellar, and Zelda prepared traditional Russian cuisine on the kitchen’s potbellied stove.16

Zelda was the creative nucleus of Arthur’s world, teaching homemade crafts to the youngsters and encouraging the boys to knit. After the Great War broke out, she and “anyone else who could knit” made socks and gloves for the soldiers overseas.17 In 1917 the family contributed to Sioux City’s Jewish war relief fund—a sum that surpassed even New York City’s—one example of the all-for-one support ingrained in Arthur.18 When armistice was announced, Zelda dressed up and paraded up and down the street, banging pots with wooden spoons, relishing in the spectacle.19 She was brazen and demonstrative in her politics, a trait Arthur would adopt himself.

After school, Arthur and Irving worked as paperboys for the Sioux City Journal, each netting forty cents a day for the family. Yet they managed to hide away a couple pennies at the bottoms of their pockets—“down south” as they called it—for a Sunday matinee at the cinema.20

Arthur was also inspired by the books of troublemaking midwestern boys by Mark Twain and Booth Tarkington. Irving later joked that Arthur “was very much the leader in creating new adventures—and creating new risks of going to jail as kids.”21 Art would admit, “I was this strange dichotomy of really being a good student in school, but a hell-raiser every spare moment.”22 In the dead of night, Arthur led the boys to the wealthy houses, slit open the porch screens, and switched the contents of their ice boxes.23 Other times they climbed their high school’s three-story fire escape, broke into the classrooms, and switched the contents of the desks. Once, they sneaked into the shed of a local sourpuss, a neighborhood butcher, ran off with his wooden buggy, and suspended it from a telephone pole.24 “We weren’t vandals,” he remembered. “There was some sort of a screwball sense of morals that I had. The idea was not to destroy anything or to steal anything, but to confuse everything.”25

Besides acts of rebellion, Arthur discovered a love of drawing in elementary school. For one school assignment, instead of drawing an assigned fairy-tale scene, Arthur drew a waterfall at sunset that the teacher hung on the wall.26 In fifth grade, Arthur refused to sing Christmas carols on religious principle. As punishment, he spent recess indoors with his teacher drawing Greek myths.27 By high school he was known as the class artist and cartoonist.28 Under his senior yearbook photo appeared three words: “A good Chresto.” The term was borrowed from Lives of the Twelve Caesars, in which Suetonius had written in 121 CE, “[Emperor Claudius] expelled from Rome the Jews constantly making disturbances at the instigation of Chresto.” Arthur had earned the reputation of class instigator.29

Outside school hours, Arthur worked several jobs to help support the family, including in a meatpacking plant,30 as a stock boy in a department store, and as a golf caddy at a country club.31 When he wasn’t drawing, he developed a fascination for the psychological science of hypnosis.32 It was the beginning of his budding interest in psychology.

He even analyzed the animals around him to the point of anthropomorphizing them. His father bought one defective horse after another, and Arthur saw that Joe the horse was “perpetually tired. Mother claimed he crossed his front legs, leaned against a convenient tree, pole or building, and promptly fell asleep the moment my father left him alone.” Then came Masha the horse, whose “speed and stamina were incredible—particularly at feeding time.”33

In 1923 Arthur’s life took a drastic turn. After school one day he discovered a crowd gathered outside his house. Inside, Solomon lay in bed, swathed in bandages and his face a bloody pulp. Beside him Zelda cut more bandages. There had been an accident. Solomon had placed one foot on the wagon’s step when Masha bucked and galloped at full speed. Solomon slipped and was dragged under his own wagon for blocks, mangling his spine.34 From then on he would have progressive and debilitating pain.

Solomon could never again be the main breadwinner for his family, and Zelda had a house of children to care for. The role now rested on Arthur, the eldest child.

The Babitzkys decided to move to Brooklyn, New York, where Zelda had family. They also knew that the move would help Arthur foster his creative potential.35 Arthur rushed to earn his high school diploma one semester early.36 In the spring of 1924, the Babitzkys started a new life in New York City.