5 Fighting for His Salary

NEW YORK IN 1924 was the glittery epicenter of the Roaring Twenties. This was the Jazz Age, and America was finding its voice.

Dreams of a better life graced both the streets and skyline. Nouveau-gothic skyscrapers dotted southern Manhattan. New York Governor Al Smith, hero of the labor reform movement, pushed policies for social welfare and public works projects.

Solomon Babitzky arrived first, working as a live-in caretaker, or shamas, in a Bronx synagogue. Arthur and Irving followed, occupying an alcove under the synagogue staircase. Arthur remembered surviving on day-old bread and expired milk, and the two pilfered from the synagogue’s Saturday kiddush luncheon. Once the others arrived, the entire family crowded into a little Bronx apartment.1 Zelda found work as a cleaning lady and Arthur as a stock boy hauling enormous burlap sacks of flour for a local grocer.

In May,2 Arthur’s fortune took an uncanny turn. He found a business card for an advertising agency in the street, called the number, and got a job.3

Arthur began an unpaid apprenticeship at the Pitts & Kitts Manufacturers & Supply Company,4 which designed interior labels for shirts and coats. For each six-day workweek, Arthur was tasked with running errands, delivering packages, and stalling creditors on the telephone. Soon he was able to try his hand at designing layouts and rough artwork. Following his trial period, his employers paid him forty cents an hour for any commercial art they used. When they realized that the ambitious teen was netting about sixteen dollars a week this way, they changed the terms of their agreement and gave him a straight ten-dollars-per-week salary.5

Arthur began to work on an art portfolio, and he was permitted to use the facilities after hours,6 setting a precedent of working late. In October, when he left punctually to celebrate his seventeenth birthday, his supervisor chastised him for not staying overtime. Disgusted, Arthur quit and took his art samples with him.7

Next,8 Arthur found work for twelve dollars a week at a more reputable commercial art agency, the Harold W. Simmonds Studio. This job also entailed running errands and the like, but Simmonds knew talent when he saw it and gave Arthur his first break on true advertising production work.

Simmonds was a strong and stocky thirty-two-year-old art-school graduate. He and his talented crew taught Arthur techniques like hand lettering, photo retouching, and airbrushing—all in the imitation-woodcut style with floral borders popular at the time. These illustrations appeared daily in newspapers and magazines advertising men’s and ladies’ fashions and products.

Arthur had an additional task he had not bargained for. According to him, each Friday it was his job to collect Simmonds at the local speakeasy before Simmonds spent everyone’s paychecks. Once at the office, Simmonds insisted on wrestling with Arthur. Once Arthur had taken a couple falls, his boss would relinquish their earnings.9 After about four months,10 the studio struck a low period, and Arthur was laid off.

But Arthur’s experience had reinforced his principles. Whether advocating for his quitting time or wrestling for his paycheck, he had an underdog’s will.

As Solomon’s disability worsened and the Babitzkys moved closer to Zelda’s relatives in Brighton Beach, Brooklyn,11 tension grew between Zelda and Solomon. Arthur’s God-fearing father was now the family’s burden.

Arthur tried in vain to freelance from home, working with a fountain pen on the surface of his parents’ bureau.12 Aware of his own artistic shortcomings, he enrolled in classes at the Educational Alliance Art School. This not-for-profit institution, located on the Lower East Side, was run mainly by volunteers and charged tuition on a sliding scale. It had been cofounded by the Young Men’s Hebrew Association and had roots as a settlement house for Jewish immigrants. Arthur must have felt right at home, especially studying under one of the school’s top instructors, Raphael Soyer.13 Soyer exemplified social realism, an artistic movement that glorified the working class. Though only eight years older than Arthur, Soyer painted his portraits of humble subjects with prodigious skill and passion.

After many months of study, Arthur began getting freelance work. Late in 192514 he opened an office of his own in Manhattan amid the growing theater district of Times Square and adopted the professional name Babbitt. He was now an independent contractor and accepted any work that came his way, including lettering, cartoons, and advertisements. His youth caused considerable confusion, and he was derided as “the boy from Babbitt’s.”15 After about nine months, he brought in a business partner to handle the layouts, lettering, and contacts.16

Ever deviating from his father, Babbitt painted butterflies on the thighs of chorus girls.17 He began a photo collection of his many female acquaintances, among them a picture of two cabaret girls blowing him a kiss.18

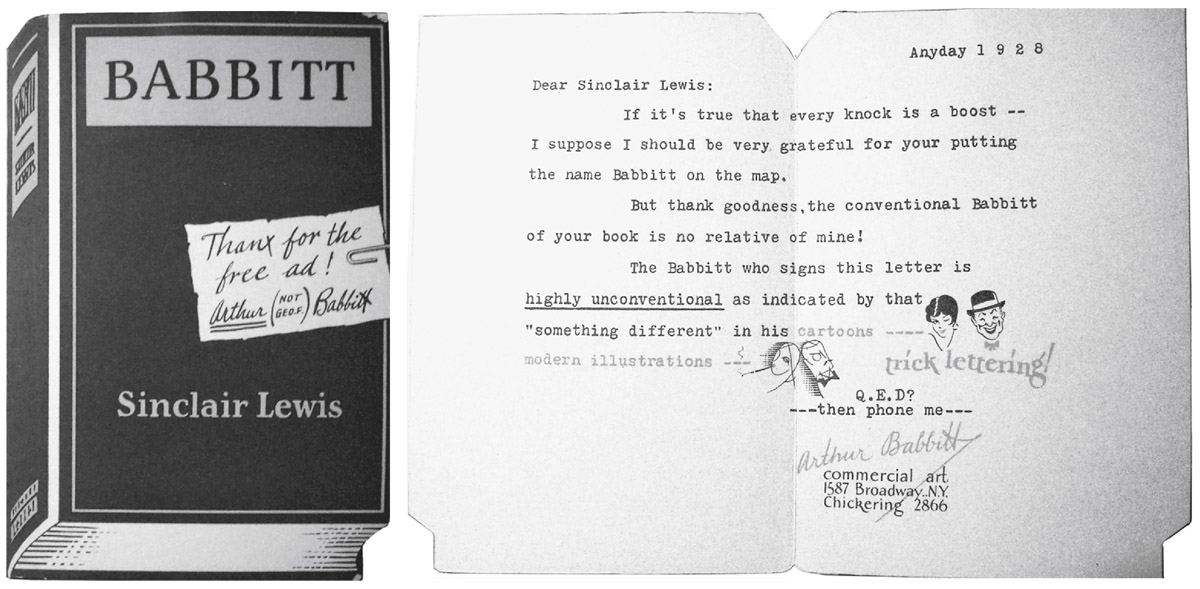

By 1927 Babbitt had integrated himself into New York’s artistic community. He had peers at the Association for Young Advertising Men, the Industrial Art School of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and the Art Students League.19 He had learned many trade secrets from his colleagues for promoting himself. An outlandish suggestion was to win a new client with a poster-sized letter sent special delivery to the client’s secretary, the boss’s gatekeeper, who was more likely to open it.20 He designed an ornate die-cut business card that opened like a greeting card. It imitated the cover of the popular Sinclair Lewis novel Babbitt, and inside were examples of his own lettering and illustration.21

Times Square in 1927 was bright with the lights of stage and screen. Vaudeville theaters promised stage shows of comedy, dance, and musical acts, while movie palaces ran the latest silent features, newsreels, shorts, and animated cartoons. The glitz of Manhattan reflected the showmanship of Mayor Jimmy Walker, who had been a popular songwriter years before.

Art Babbitt’s business card.

When Babbitt’s commercial building was to be demolished to make room for the Ethel Barrymore Theatre, he relocated around the corner to 1587 Broadway on 49th Street. Coincidentally, this was next door to the Strand Theatre, where Carl Eduarde conducted his musicians who would play for Steamboat Willie. In the summer of 1928 Walt Disney and Art Babbitt likely stood within spitting distance of each other.

For fun, Babbitt fostered his love for fine music, practicing the mandolin and listening to classical radio. Being in New York City, he could find inspiration all around him, from the music clubs to his Italian barber, whose witticisms included, “Death—she’s anot such a bad athing in life!”22

In the summertime, he joined friends at the beach, accompanied by Rose Cohen, a brunette from Passaic, New Jersey. She came from a large, well-to-do Jewish family, but like Babbitt she was the child of Russian immigrants, and also a designer herself, specifically of hats. She was Art’s first courtship, and in January 1929 the two were engaged.23

Babbitt’s career was expanding. In his midtown studio, he landed an illustration assignment for Scientific American.24 Soon he accepted an animation project for a local medical institution, making instructional short films for educational screenings. He acquired a camera and animation stand and started animating these moving diagrams. (Today animated visual aids are called mechanisms of disease and are still used in hospitals and medical schools.)

He was not enthralled by the medium of animation itself—it was little more than a novelty as far as he was concerned. Then, around September 1929, while at the cinema, he was struck by the opening cartoon. It was Walt Disney’s first Silly Symphony, The Skeleton Dance. In those six minutes, Art Babbitt became a Disney fan.

Arthur and Rose were married on September 29, 1929. From the start, she and her family dominated. The wedding was a high-profile ceremony in the Park Manor, Brooklyn’s premier kosher catering hall. It was attended only by immediate family and the bridal party; all of Babbitt’s groomsmen, including his best man, were Rose’s brothers. Immediately following the wedding, Art and Rose honeymooned in Bermuda and returned on October 14 to their new home in the suburbs of Passaic, New Jersey.25

Two weeks later, the stock market crashed; the Great Depression had begun. Babbitt’s business accounts started drying up. His business partner mentioned that Paul Terry, the successful animation director of Aesop’s Fables, was organizing his own cartoon studio in the Bronx and was looking to build its staff.26 Babbitt would have dismissed it if not for one thing: Terry was making cartoons with sound. Babbitt closed his business and got an entry-level job at Terrytoons for thirty-five dollars a week.27 His first task was opaquing the inked cels with paint and then, after they were photographed, washing them at night for reuse, earning an additional penny apiece.

Paul Terry had opened his studio in Thomas Edison’s former production building.28 In 1929 the lower floor was still used for costume storage and a soundstage rental space. Upstairs, a staff worked for Paul Terry to produce a six-minute cartoon every week. Each cartoon amounted to roughly forty-three hundred drawings.

In the high-ceilinged Terrytoons studios, a room of animators sat at their animation desks in rows like garment workers. Each desk was equipped with a large hole in the center on which sat a circular pane of frosted glass called a light disc, through which a lightbulb underneath could illuminate several drawings stacked atop one another. The animators flipped their drawings of main poses back and forth. Babbitt learned that these drawings were called extremes, and the drawings that connected them were called inbetweens. In this well-oiled assembly line, drawings went from the animators to the inbetweeners to the cel inkers to the opaquers to the camera, and finally to the editor who viewed the undeveloped film footage on a Moviola machine.29

In his cardigan and glasses, Paul Terry was the image of a father figure, though he was only forty-three. He had been animating since 1915 and was one of the company’s four supervising animators, along with Jerry Shields, Frank Moser, and his older brother John Terry.

Paul Terry had his own office away from the other animators, where he worked out schedules for budget and distribution. He was notoriously cheap. His studio furniture was a hodgepodge from thrift stores and estate sales. He kept daily records of each artist’s productivity to ensure the studio churned out cartoons weekly. He referred to his product as “merchandise,” and he refused to make a cartoon any longer than the bare minimum. Producing more than the required six minutes was, he later said, “a waste because we never got a nickel more for it.”

There was no story department. Instead, Terry pulled from a gag file, from which he would proudly “take elements that already existed and put different combinations together. And then you create something seemingly new.” He had A gags for big laughs, B gags for medium laughs, and C gags for chuckles.30 “I’ve got the finest collection of jokes in the world,” he said. “I save jokes, because they never change. They’re good from one generation to another.” He saw no point in having style guides or model sheets for his characters. It was a seller’s market, and as long as theaters kept buying, Terry saw no reason to change.

Around late February 1930 Babbitt graduated to trainee animator under Frank Moser.31 Like Terry, Moser kept careful track of how much animation each worker produced, even counting each employee’s bathroom time. Moser himself was responsible for roughly half the footage of each cartoon, often bragging that he was the fastest animator in the business. Babbitt thought, That’s like being the fastest violinist in the world—he can’t play worth a damn but he can sure play fast.32

Nonetheless, Babbitt enjoyed working alongside John Terry. John had a side job writing and drawing his comic strip, Scorchy Smith. He had tuberculosis and at times would start laughing at his desk for no apparent reason. When asked what was so funny, John Terry would smile and reply, “Every day is gravy.” This memory of random, apparent carefree laughter stuck with Babbitt, worming its way into his ever-growing mental library.33

Because the four supervisors were older—all born in the 1880s—and had worked as newspaper illustrators, they approached animation as comic strips in motion. However, Babbitt’s generation had been influenced by vaudeville and movies. For the youngsters, it was not the image that made the humor but the way the image moved.

Babbitt tested animation by flipping his drawings at his desk. His art classes had taught him that growth comes from experimenting and trying new things. But at Terrytoons there was no experimentation; all animation was final. Animators saw their completed animation only after two months, when a final print was developed and returned. Terry required all animators to stick with actions they already knew how to do.

When the studio’s twelfth cartoon, Monkey Meat, began production in May 1930, Babbitt was finally a character animator on his own. His first scene was a monkey playing a hippo’s teeth like a xylophone34, a gag used in Disney’s Steamboat Willie two years before.

Original layout drawing by Art Babbitt of his first-ever character animation scene, from Monkey Meat, 1930, at Terrytoons.

Around the shop, some folks talked about Terry’s “good animator” who was studying fine art in Europe. Then late in December 1930 he arrived, resembling a tall, mustachioed Cossack with a New York accent. His name was Vladimir “Bill” Tytla.35

Today, Tytla is considered one of the greatest animators who has ever lived. In those early days, Babbitt couldn’t ignore Tytla’s energy, describing “little sparks of electricity coming off of him all the time.”36 Babbitt and Tytla had a lot in common. Their parents were immigrants; each bubbled with ambition and industriousness. It was not long before a friendship blossomed. Babbitt teased Bill’s Ukrainian heritage by calling him “Vladjo.” Tytla teased Babbitt’s skinniness by calling him “Bones.”

Babbitt introduced Tytla to fine music, and Tytla opened Babbitt’s mind in other ways. Tytla introduced Babbitt to fine art and to the socialist novel Penguin Island, and he brought Babbitt into his circle of commercial artists.37 Above all else, Babbitt credited Tytla with giving him the courage to be creatively inventive.38

Soon Babbitt began to flourish at Terrytoons. He delivered scenes better and faster. Periodically, Paul Terry’s wife, Irma, popped into the studio and goaded Babbitt to negotiate for a raise. “Go in and tell Paul you want fifteen dollars more a week or you’re going to quit, and then you’ll get five,” he recalled her telling him. Babbitt did so more than once, and each time received his raise.39 The episodes reinforced Babbitt’s notion that employees had to fight for their fair share.

Some of the top Terrytoons Crew, circa early 1931: (left to right) Jerry Shields, Bill Tytla, Frank Moser, Art Babbitt, Charles Sarka, unidentified, Paul Terry.

By early 1932 Babbitt supplemented his income contributing drawings to a humor magazine called Merry-Go-Round. He also kept his sights on Disney. For one magazine gag, he drew Mickey Mouse responding to the 1932 presidential race.40 Furthermore, a one-time Paul Terry animator from the Van Beuren studio, Norm Ferguson, had become a supervising animator at Disney.

Rose Babbitt was not enthusiastic about Hollywood. She had a life in Passaic and a job designing hats at Bergdorf Goodman in New York.41 According to Babbitt’s cousin, Rose “didn’t give him breathing space.”42 The two separated, and Babbitt stayed with Tytla in his Bronx apartment. They eventually divorced, and Babbitt would fail to even acknowledge that they were ever married.43

Using a strategy that he had picked up as a commercial artist,44 Babbitt made a run for Disney. He bought an enormous piece of paper—about fifteen feet by twenty feet—got down on his hands and knees, and wrote an enormous request for an interview.45 He addressed it to Walt Disney’s secretary, Carolyn Shafer, and mailed it special delivery.46

In May 1932, activism and corruption proliferated in New York. Seventeen thousand destitute war veterans marched to Washington, DC, demanding an advance on their military bonuses. On May 14 a hundred thousand New Yorkers marched for the end of Prohibition in the We Want Beer parade. On May 25, the charming and charismatic mayor Jimmy Walker was ordered by Governor Franklin D. Roosevelt to testify under suspicions of corruption. (He would retire from politics that November.)

May was also a milestone for Art Babbitt. It was the month he received a call to interview with Walt Disney.

Illustration Babbitt drew while still in New York for the humor magazine Merry-Go-Round, commenting on current events and parodying Mickey Mouse’s popularity. From summer 1932. Mickey Mouse © The Walt Disney Company.