16 A Growing Divide

In the six weeks between Snow White’s roaring Hollywood premiere and its 1938 general release, the Disney studio truly felt like a place of wonder. The screening was proof that this film of theirs would last the ages. Now the critics were loudly and unanimously raving about it. Columnist Westbrook Pegler called the film the happiest event since the armistice that ended the Great War.1 Walt Disney was hailed as a genius. The months of unpaid nights, mornings, and weekends had paid off. Now all that the employees had to do to collect their promised bonuses was to wait for the ticket sales.

It was particularly gratifying for the old-timers who had worked with Walt since the early days. Chief legal counsel and senior vice president Gunther Lessing was one of them. Oddly, he had stumbled into the film industry by accident.

Born in 1886 of a German-Jewish father in Waco, Texas,2 Gunther Lessing graduated from Yale Law School in 1908 and earned the top score on the Texas bar exam.3 He left to work in El Paso, situated near the Texas-Mexico border, and established himself as a “high-priced lawyer.”4 There he built a reputation of both legal competence and Mexican cultural fluency. In January 1914 Lessing began working with two powerful entities: the Mutual Film Corporation (which had just signed D. W. Griffith to produce Birth of a Nation) and the leader of the Mexican Revolution, General Francisco “Pancho” Villa. Lessing brokered Villa’s exclusive $25,000 contract with the studio interested in dramatizing his life.5 He continued working with Villa as his personal attorney, a source of humor and pride that Lessing would often mention during his years at the Disney studio.

However, Lessing had his secrets. In 1917, after he opened a law firm with two partners in El Paso,6 he was sued by his own employee, attorney Eugene S. Ives. Lessing had contracted Ives to handle a case in Arizona for $350. Ives had worked overtime, unpaid, to successfully reduce their clients’ bail by $1,000. Following the assignment, Ives demanded a higher fee from Lessing and brought him to court. His grounds were what is known as quantum meruit—a deserved compensation that goes beyond a legal agreement. Ives lost the case, even under appeal: the requirements of his compensation were constrained to his contract, nothing more.7 This ruling would eventually dictate how Lessing maneuvered the Disney studio’s bonus plan.

Although Pancho Villa was assassinated in 1923, Lessing stayed close with the Mexican revolutionaries. He witnessed actress Dolores del Río participate in the rebellion of late 1924 to early 1925.8 Del Río was a Mexican silent film diva and one of the first great foreign-born stars of Hollywood. In July 1927 Lessing signed a four-year, $35,000 contract as del Río’s personal attorney.9

For a time, Lessing and del Río had an amiable working relationship. She, Lessing, and their mutual spouses—Jaime and Loula—attended Hollywood parties together.10 That’s when Lessing first met with Walt Disney, at the time a young cartoon producer who had just lost production rights to his Oswald cartoons. Around 1928 Lessing began working for Walt as a part-time legal consultant.11 It was Lessing who helped Walt protect the copyright of Mickey Mouse.12

Lessing continued to work for del Río in various capacities, including handling her and Jaime’s amicable divorce in 1928.13 However, the stock market crash of October 1929 and Jaime’s sudden death from surgery complications shook her.14 She attempted to curtail Lessing’s contract, and paid him $4,000 for services rendered. Lessing sued her anyway, for “lack of gratitude and appreciation” and the $31,000 balance.15

While del Río was sucker punched by these events, Lessing’s situation was more stable than most. He started working for Walt Disney full time on January 1, 1930.16

Del Río spitefully reached out to support Lessing’s despondent young wife. Loula was trapped in a miserable marriage, accusing her husband of throwing water in her face at a party, dragging her around by her ear in front of their friends, and turning her ten-year-old son against her.17 In July 1930 Lessing foisted a second lawsuit on del Río for encouraging Loula to divorce him. During the separation, while Lessing sent Loula and his stepson a paltry forty dollars a month, del Río supplemented the sum from her own pockets.18 This enraged Lessing further.

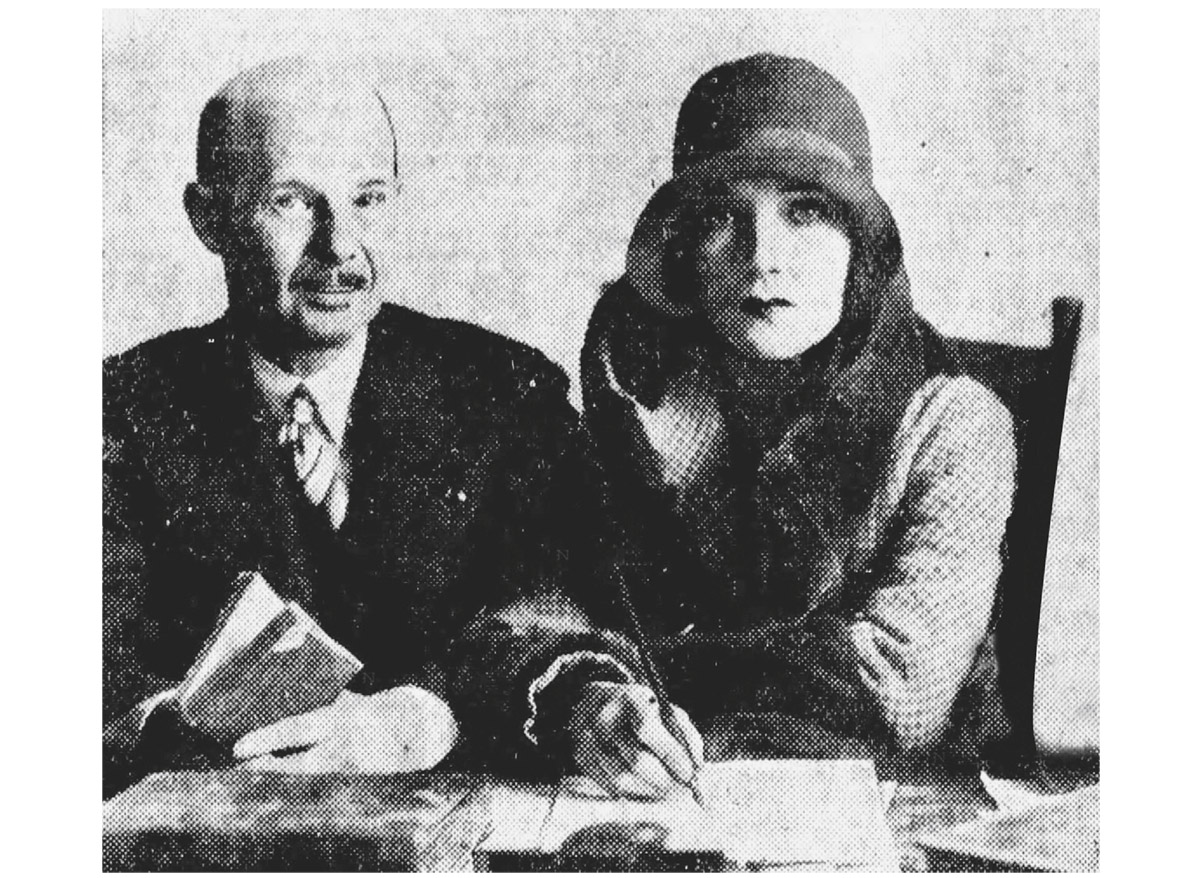

Gunther Lessing and Dolores del Río in a press photo taken April 1928. The photo appeared in a New York Daily News story on July 24, 1930, under the headline CHARGES DOLORES DEL RIO TURNED WIFE AGAINST HIM.

While testifying publicly against del Río, Lessing argued that he protected her against hypothetical bits of bad publicity. He went on to openly discuss examples of her overt sexuality and sexual proclivity.19 This lawsuit vilified del Río as a “home wrecker” in the press.20 According to del Río’s biographer, “Lessing’s legal action seemed designed to destroy her.”21

Lessing won a $16,000 settlement against del Río in December 1931.22 Loula was granted her divorce from him in April 1932.23

In all the press about the del Río case, Gunther Lessing was never linked to Walt Disney Productions. The Disney artists remained oblivious to Lessing’s sordid connection with this empowered movie starlet.

And that was just how Lessing wanted it.

The Disney artists who had just completed Snow White jumped into the next big project, Pinocchio, brimming with confidence.24 Art Babbitt began working on the Geppetto character, doing some animation tests in his opening sequence as a bald, roly-poly sourpuss. The design had already been approved, and Geppetto’s personality was deduced with Stanislavski’s “character analysis” in mind: since Geppetto lived alone, he would be used to getting his way, but since he wished for a son to love, his rough exterior would belie a heart of gold.25

True to the source material, young animator Frank Thomas began experimenting with Pinocchio as an obnoxious and clunky puppet. Thomas was among the newly minted art-school graduates hired between 1933 and 1935 and who were climbing the ranks at incredible speed.

After months of story conferences, Pinocchio’s working script was progressing. It included a Grandfather Tree, an ominous town solider, a nightmarish Bogeyland, and a birthday party finale.26

Of course, the Disney studio continued producing shorts, which brought in a steady revenue stream and reinforced the branding of its cartoon stars. By New Year’s 1938 Babbitt was just beginning his animation for the new Goofy and Donald cartoon, Polar Trappers.27 Although Babbitt had already been crowned a Goofy specialist, Goofy’s animation direction for this cartoon was assigned to Woolie Reitherman, probably because Babbitt was occupied with Geppetto and Reitherman had some experience animating the Goof. Babbitt was assigned two long establishing scenes of Goofy lazily preparing a walrus trap and a walrus stealing his bucket of fish.

However, Babbitt’s brief sequence cuts abruptly to the first of Reitherman’s many scenes. Under Reitherman’s pencil, Goofy zips straight into a fast-paced cartoon chase. Racing in skis and wielding a lasso, Goofy becomes an emblem of sportiness. Reitherman’s Goofy has eyes that are wide open and alert, and movements that are quick and impulsive.28

Babbitt would have just started to notice a trend: the younger artists were slowly taking the most coveted assignments. The top artists who had initially elevated Disney animation—men like Babbitt, Norm Ferguson, Fred Moore, Dick Lundy, and Bill Tytla—were beginning to be eclipsed by the art-school graduates. In the depths of Babbitt’s gut was born a realization: he and his peers were replaceable.

After his conversations with Gunther Lessing in December, Babbitt spearheaded a company-wide group to block an IATSE takeover. Around the start of January, with Lessing’s knowledge, Babbitt met with the Los Angeles regional directors of the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB). The board made it clear that if this group was going to exist at Walt Disney Productions, it required a few things:

Its own constitution.

A president.

An elected executive board.

A list of demands.

Membership from the majority of Disney employees.

Recognition from the company as its employees’ sole bargaining organization.

One of the NLRB’s regional directors, William Walsh, gave Babbitt a list of attorneys and suggested that the meetings be off company time and property.29 Babbitt and his colleagues who made up the temporary executive board, including Norm Ferguson,30 selected Leonard Janofsky, lawyer for the Screen Writers Guild with experience in NLRB cases.

Babbitt held the first executive board meeting in his and Marge’s home. Fourteen Disney employees from different departments made up this board and attended the meeting.31 As with his home-hosted figure drawing sessions, Babbitt was quick to take initiative. Janofsky introduced himself as the group’s legal counsel, and employees drew up a constitution and bylaws for Janofsky to review and revise. They also chose a name for their group—the Federation of Screen Cartoonists.

Gunther Lessing was also in Babbitt’s house that night. He spent the evening not participating in the meeting but talking with Marge in the parlor, pouring some drinks at the bar, and adjourning to the fireplace.32 This was the last time Lessing was invited to such a meeting. Lessing’s presence in the adjoining room reveals that he had planned to attend but was excluded at the last second. The only new element was Janofsky, who could see that the group was attempting to form a union, and therefore management was forbidden to participate. Lessing had tried to shape the group as a loosely knit social organization to his own liking, but now it was evolving outside his control.

Around Monday, January 24, Babbitt placed a notice on the company bulletin boards: “A mass meeting will be held in the Hollywood American Legion Auditorium, Thursday night, Jan 27th. Your future in this business is concerned—so it is imperative that you be there WITHOUT FAIL. Supervisors and production heads excluded.” At the bottom of the flyer it read, “Persons not employed in this studio will not be admitted.”33

At “8 PM sharp,” Babbitt and Janofsky led the meeting at the auditorium, laying out the Federation’s purpose, according to its constitution: “To bargain collectively for its members, with Walt Disney Productions, Ltd., with respect to rates of pay, wages, hours and other conditions of employment.”34 If any member of the Federation had a grievance against the company, that member would communicate it to a representative on the executive board. That board member would be empowered to bargain with management on behalf of the employee, and any settlement would be voted on at a Federation meeting.

The executive officers were chosen, and Babbitt was elected president.35 Members of the executive board were appointed among employees from every department.36 The demands were typical of a Hollywood union in 1938 but also emphasized resistance against the Bioff-held IATSE union:

1. “Higher pay for lower-salaried brackets.”

2. “A forty hour five-day work week.”

3. “In case of lay-off, two weeks’ notice.”

4. “A stipulated period of apprenticeship, varying with the need of different departments.”

5. “The blocking of outside intervention, be it the Producers Association, the IATSE, or anyone else interfering with the employees’ rights.”

6. “The recognition . . . of a Grievance Committee to hear, judge, and correct the injustices suffered by any of our members.”37

Though the employees were not resounding with complaints, each of these demands was enticing to many Disney employees, for different reasons:

1. While some top-level artists like Babbitt were earning high salaries, lower-salaried Disney employees had become the lowest-paid in the industry. A Disney inbetweener earned $22.50 a week, whereas an inbetweener elsewhere earned $28 a week.38 Starting Disney painters earned $16 a week and inkers $18 a week. By contrast, an entry-level set-painting job in Hollywood started at $35 a week.39

2. While some other sites had adopted a five-day workweek, Disney artists were expected to work half-days on Saturdays.

3. The Disney artists had witnessed their share of sudden layoffs.

4. A period of apprenticeship could be endless, or it could end with a termination. Inbetweeners were brought in for a “tryout period,” fifteen at a time, after which all but three might be fired.40 During the Ink & Paint Department’s tryout period, someone was fired every Friday. Remembered one inker, “Everyone was so scared and worried they could hardly relax enough to do their work.”41

The Federation membership quickly signed up 550 of the eligible employees. On Monday, January 31, the Federation of Screen Cartoonists announced itself to Disney management in a letter. It stated its purpose, explained that it represented a majority of Disney employees, and requested recognition as the studio’s union.

Two days later, the Federation received a mixed message from the company. There was approval: “The purposes of your organization appear to be laudable and that we do not object in principle to bargain collectively with our employees.” But there was also resistance: “There are other organizations that claim jurisdiction on the premises. We believe that you . . . should settle the question of jurisdiction before approaching us for recognition or meetings.”42

This required extra legwork from Babbitt and his colleagues. The Federation would need certification from the NLRB—a charter—so it filed a petition with the NLRB on February 11. The NLRB responded on February 16, stating that it was waiting on a decision for a different case—one involving the Screen Writers Guild—that would determine the outcome of every motion picture case that was still pending. Babbitt had to wait.

There was suddenly a lot of waiting at the Disney studio. Pinocchio had serious problems, and Walt could feel it. “One fear is constantly before us,” said Walt then, “the fear that our next effort will not be regarded by the public as highly as the last.”43 Walt’s own pursuit of excellence set him up for indomitable pressure.

The script needed work, and the characters needed revision. More than sixty seconds of finished Geppetto animation were discarded.44 The writers started from square one again, and Pinocchio was moved from the Animation Department back to the Story Department. There was now less for the animators to do around the studio. Bill Tytla began work animating the sorcerer for The Sorcerer’s Apprentice. Babbitt was instructed to keep busy as best he could. His friend Dick Lundy was directing a new Donald Duck short called The Autograph Hound and gave Babbitt some scenes to animate.

During slack periods, temporary layoffs were expected. Higher-level artists had a clause in their contracts that allowed for layoffs up to four weeks without pay. Even so, the studio chose to keep Babbitt on.45

Ever since the Bioff-led IATSE announced its plan to pursue all Hollywood crafts, those crafts rose up to block the IATSE. Hollywood alliances were formed.

Walt Disney Productions stood apart from the rest of the animation industry, but the smaller studios were hell-bent on blocking IATSE too. The independent animators’ union called the Screen Cartoon Guild sought to unite artists from all studios, just like other unions. It held get-togethers with guest speakers, which were “open to all cartoonists in the animated cartoon industry whether members of the Guild or not.”46

The Guild went so far as to approach the artists of the Disney studio, even claiming to have signed up some of them there.47 That would make the Guild the third union to try to organize Disney animators, after the IATSE and the Federation.

But the IATSE was the common enemy of both the Guild and the Federation. On Friday, February 18, committee members of both the Guild and the Federation met and agreed not to interfere with each other. “We have one common objective,” the Federation wrote, “to keep the IATSE out, and we’re going to do it, cooperatively.”48

In a bright and smoky country club ballroom, the Disney artists danced, drank, and laughed. A red-hot swing band played as the female vocalist crooned. It was March 12, and the Federation of Screen Cartoonists had sponsored its first social event.49 It was the closest thing to a wrap party that the Snow White crew had, and Babbitt had organized it. This party might have stood as the only party the studio was to hold. That was not the impression Walt wished to cultivate, and he began to brainstorm another, bigger celebration of his own.