27 The 21 Club

The Guild continued hitting Walt where it hurt—in his public image. “A bankroll can change a lot of things, including a nice kid from Hyperion,” wrote the L.A.-based magazine Radio Life on June 15. “A lot of good guys and gals helped make Disney in a spirit of cooperation, and now it’s mostly corporation. Maybe Disney ought to renovate his soul.”1

Walt considered this a smear campaign, but some supporters took things further. They formed a secret society, calling themselves the “Committee of 21” and hoisted an attack on the Guild.2

The committee’s first letter arrived on June 16 and was also sent to several non-AFL Hollywood unions. It was a lengthy, rambling diatribe of extremism and conspiracy theory. It warned that the strike was funded by Russian Communist groups and that Aubrey Blair and Herb Sorrell were using the Labor Relations Board “to pull the RED HERRING of ‘Patriotic cooperation’ to divert you from the certain failure.”3

The strikers wondered aloud who composed the Committee of 21. Some suspected it was Willie Bioff’s goons. Bioff had been in the news a lot lately, having recently been extradited to New York to face an extortion charge. On Tuesday morning, June 17, Babbitt tried to reassure the strikers. They did their best to belittle the anonymous group, and printed a mock invitation: “The Committee of 21 meets, secretly, every nite. Bring your mask, 1 Junior G man badge, 1 Superman cape and a suitable holder to swing a red herring with.”4

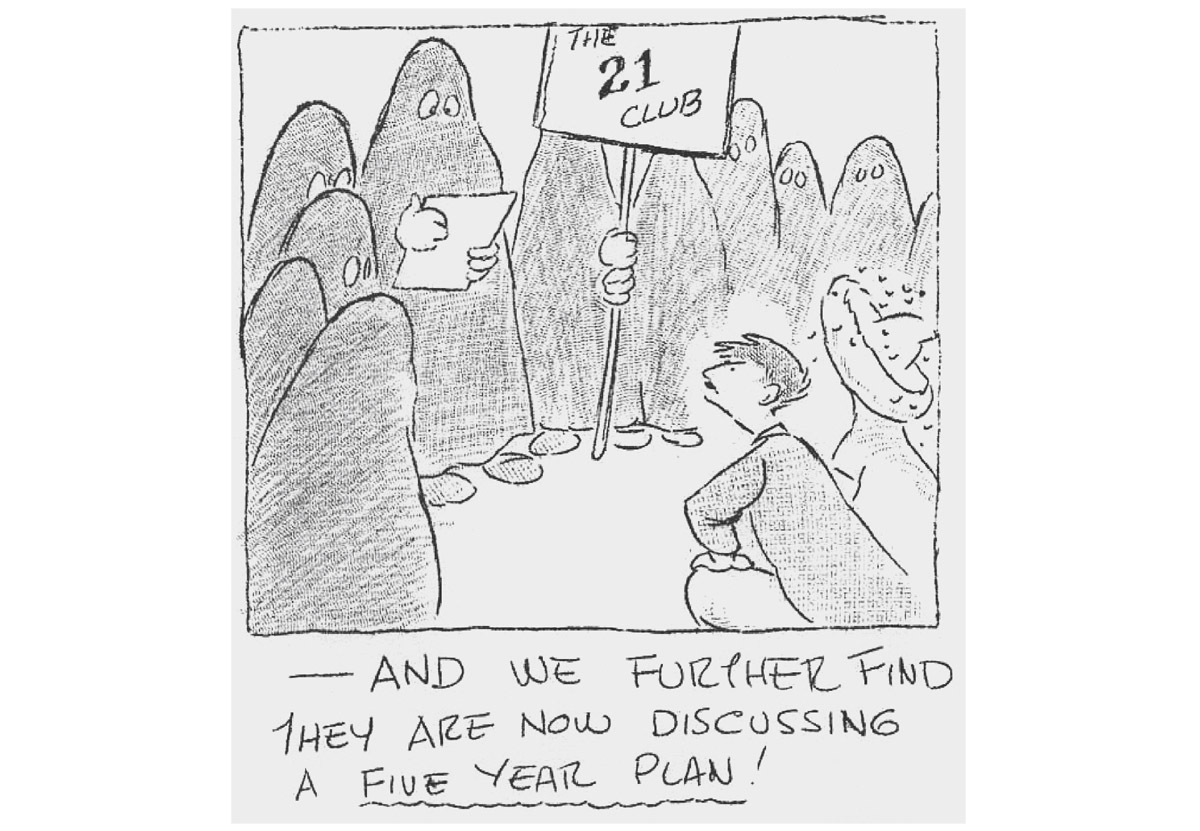

Strike leadership presumed the anonymous group was composed of the high-ranking Disney artists who belonged to the studio’s Penthouse Club. Thus, the Committee of 21 earned the moniker the “21 Club.” Their accusations now became associated with the most privileged Disney loyalists.

One Disney striker’s rendition of the Committee of 21, as seen in their daily newsletter On the Line on June 17.

Nevertheless, Walt continued seeking a solution. He had hired an IATSE lawyer, Harold V. Smith, to mediate a strike settlement. Besides representing the IATSE soundmen, Smith was also chairman of the business agents’ committee of the IATSE. Meetings between Smith and the Guild started on Monday, June 16. Smith proposed making the studio 80 to 90 percent Guild membership, barring an election, and a reinstatement of all employees, with one exception: Art Babbitt.

The Guild presented its counterproposal—a 100 percent Guild shop, barring a cross-check, and a reinstatement of all employees including Art Babbitt.5

Guild attorney Bodle reiterated his willingness for an election under the auspices of the Labor Relations Board. However, the board could not conduct the election while charges of company domination against the ASSC were still pending. Then the Guild learned that the company was hiring art-school students to help finish up Dumbo. Babbitt wrote in a handbill, “The strikers feel [Walt] is now suggesting an election as a bid for public sympathy.”6

Meanwhile, Roy traveled back to New York on the weekend of June 14. He had one goal: meet with RKO and convince the company to distribute Disney films again.7

Harold Smith met with the Guild representatives again on Wednesday, June 18. This time, Smith shared a new development from the studio: Disney loyalists were dismantling the ASSC. They were now organizing another company union, this one called the Animated Cartoon Associates (ACA). They claimed four hundred members and were prepared to call the Labor Relations Board to authorize an election. As if to strengthen its claim to legitimacy, this studio union pledged to have different board members than the last two.8

Now in its fourth week, the strike was taking a toll on the picket line. There were a few glimmers of joy; four couples had been married since the strike began, including Bill and Mary Hurtz. The Women’s Auxiliary had set up day care for the Disney strikers’ toddlers. But some strikers who were living hand-to-mouth were getting behind in their rent. Others were relying on the strike soup kitchen for free meals. William Littlejohn wrote a letter to the Guild representatives desperately asking for help.

On June 19 Chuck Jones organized a parade of Warner Bros. animators delivering a truck of food for the Disney strikers, under the banner BUNDLES FOR DISNEY and a sign reading, LOOK FELLAS, MANNA! Jones brought up the rear staggering under a big sack of potatoes.

The Women’s Auxiliary doubled their efforts. They organized an industry-wide art sale with the help of the women at Warner Bros. animation. The fundraiser would sell original sketches, watercolors, and ceramics throughout the week, from noon until 9 PM, for up to ten dollars each. Disney art teacher Gene Fleury helped organize the event.9 The women also planned a mammoth street dance and carnival fundraiser right outside the studio.

Guild meetings on the eucalyptus knoll were now focused on keeping spirits high. All strikers with special talents were encouraged to participate. An entertainment committee was formed. There were magic shows, costumed skits parodying Walt and “Gunny,” and sing-alongs. One song in the tune of “Little Brown Jug” began:

I’m the Kansas City Kid

Do you know what I have did?

Fired Guild leaders up and down

And gave them all the run-around.

Chorus:Yo-ho-ho, you and me

Little red axe, how I love thee.10

Screen Actors Guild members showed up for support. Actor John Garfield marched with a sign in the picket line. Frank Morgan, the Wizard of Oz himself, spoke with Bill Tytla atop the knoll.

Something ignited in Tytla shortly thereafter. He went rogue and tried to broker a peace with Walt, man to man. The details differ: Tytla either approached Walt at a café or telephoned Walt over the weekend. Either way, the mission failed.11 Some loyalists laughed at Tytla’s “peace proposal,” calling it “a wild, hair-brained idea.”12 It was also a sign that the strike’s united front was cracking.

Loyalists, including top creatives like Norm Ferguson, Fred Moore, Dick Lundy, and Wilfred Jackson, gathered in the Roosevelt Hotel on Thursday night, June 19. The meeting confirmed the disbanding of the ASSC and the establishment of its replacement, the Animated Cartoon Associates.13

Suddenly they heard a ruckus outside the doors of the large meeting room. The meeting had barely begun when fifty strikers stormed the hotel, screaming from the lobby and pushing through the doors. A few of the larger loyalists held them off. A striker swung with a hand that had drawn Dumbo storyboards and was punched with a hand that had animated Mickey Mouse in Fantasia. A loyal character designer, Jim Bodrero, got between the two and yelled to have no bloodshed as others pulled them apart. The strikers remained in the lobby while the loyalists returned to their meeting. Norm Ferguson and Fred Moore were nominated for the ACA’s steering committee. Bodrero was elected president. “Good meeting,” opined a loyalist that day, “we had good unity.” After the meeting, ACA members discovered that strikers had stabbed their cars’ tires with ice picks.14

The drama was too much for some officials within the Disney studio. Both the director of film distribution and the head of eastern publicity had resigned.15 Now, upset at the company’s discriminatory layoffs, production control manager Herb Lamb quit as well.16

Around Wednesday, June 23, the Committee of 21 disseminated its second letter. “YOU ARE LOST, because the Public and the entire Union Labor Movement is alert to the Communistic issue your stupidity has exposed.”17

The Disney strike was starting its fifth week. The strikers were weakening, and it was starting to show. “We have been ragged by the vicious and unfounded accusations of the now notorious, if still anonymous, ‘21 Club,’” they wrote.

Chuck Jones once again led the Warner Bros. artists in a parade, this time staging a mock funeral. The men dressed in black suits; the women wore black dresses and veils and carried large prop candles. Six of the men (with Jones in the rear) carried a large, hand-crafted coffin on their shoulders like pallbearers. On the side of the coffin was elegantly painted “R.I.P.—F.S.C.” Behind them, weeping widows in black dresses and black shawls over their heads carried signs that read, “A.S.S.C.” and “A.C.A.” The “mourners” placed the prop candles in stands and dabbed their eyes with handkerchiefs, wailing over Disney’s three company unions.

Roy returned from New York on June 24.18 He had convinced RKO to distribute The Reluctant Dragon. The strike had delayed the film by nearly a month.19 Dragon finally premiered that Friday at Broadway’s Palace Theatre in New York to a rousing, sold-out audience.20

Saturday night, June 28, was the strikers’ big street dance fundraiser. Festivities began at 8:30 PM; admission was twenty-five cents. Big-band music rang out along South Buena Vista Street and Riverside Drive. There were hot dogs and beverages, carnival booths, and a bonfire. One striker had a caricature station while another had a fortune-telling table. A third put on a medicine show, and others staffed a kissing booth. From the studio rooftop, Disney security flashed their searchlights down at them. It was a night of fun and optimism. Many, including attorney Bodle, was sure that the strike would be settled soon.21 By the end of the night the benefit had raised $570.22

On Sunday the New York Times published a featured article on the Disney strike. It quoted strikers calling Walt an “egocentric paternalist,” a far cry from his portrayal in The Reluctant Dragon.23

Walt could take it no longer. That very day he drove to the San Fernando Valley. He had tried working with his own labor counselor (Walter Spreckels), an independent labor counselor (Pat Casey), the Los Angeles Central Labor Council (Messrs. Sherman, Buzzell, and Blix), and a business agent from IATSE (Harold Smith).

He had one last recourse for ending the strike on his own terms.