23 Disney Versus the Labor Board

HOLLYWOOD CULTURE IN EARLY 1941 was a tenuous balance of glitz and social upset. Labor news was everywhere, and on a daily basis—one only had to pick up the trade papers. Strike threats were commonplace, used strategically to achieve a union contract. Nearly always a strike was averted by a company’s use of poise and diplomacy. Unfortunately, Gunther Lessing possessed those two qualities in increasingly short supply.

At the Academy Awards on February 27, 1941, Pinocchio won awards for best score and for the song “When You Wish Upon a Star.” As for the Best Short Subject: Cartoons category, Lessing had not sent in a single submission. He was bitter that the Academy had not accepted Fantasia for this year’s competition, though it had premiered in November. The Academy said it could be submitted next year, but according to the rules, Fantasia’s general release in January 1941 disqualified it among the films of 1940. As a result, the winning short cartoon was MGM’s The Milky Way. Directed and produced by ex-Disney employee Rudolph Ising, it beat out the first cartoons to star Bugs Bunny and Tom and Jerry. Disney had won the Academy Award in this category every year until now; this event forecast a changing tide in Hollywood cartoons.1

Back at the Disney animation rooms, Bill Tytla helped Ward Kimball on his dancing crows for Dumbo, and Kimball, in turn, attempted to help Fred Moore on Timothy the mouse. Kimball found his efforts to be futile, reflecting, “Fred is so used to success that when a real problem faces him he doesn’t know what to do.” A sketch cropped up of Fred yelling, “Help! I mean it; I used to knock this stuff out right and left.”2

In one of Moore’s sequences, Timothy becomes intoxicated after falling into a bucket of spiked water. Moore struggled with animating the drunken Timothy and ended up digging into the studio’s reference library (“morgue”) for Babbitt’s animation of Abner the drunken mouse. Moore watched the reel and flipped the original drawings. He even pinned some of Babbitt’s drawings to his desk as he worked.3

Babbitt was fighting his own demons as well. His assignment of Mr. Stork had taken weeks longer than expected. When he was nearly finished, he informed the supervisors that he was ready for his next scenes. However, for the first time in years, there were none to be had. Additional Dumbo assignments for Babbitt had mysteriously dried up. In the wake of mass budget cuts, Babbitt’s job was only as stable as his deliverables. If there was not enough work to justify employment, an artist would be laid off, as many had before.

Babbitt called Walt’s office from his office phone. As Babbitt recalled in 1942, Walt told him that he was so hard to get along with that none of the directors wanted to work with him. It was a surprise to Babbitt. Except for Sam Armstrong (director of Fantasia’s mushroom sequence), Babbitt had never had difficulty with directors. He immediately went to each director’s room one by one to ask them point-blank if this was true. Bill Roberts, Wilfred Jackson, Ben Sharpsteen, and all the others denied that they told Walt this.4

Ultimately, Babbitt was given a Dumbo sequence, but one far below his skill level—clowns silhouetted against a circus tent. Three such sequences were in the film, with the other two assigned to junior animators. In Babbitt’s sequence, the clowns decide to organize, singing that they’re “gonna hit the big boss for a raise.”5

Babbitt said nothing about it. He had already been warned by Guild attorney George Bodle and the Labor Relations Board’s field examiner, George Yager, to watch his step. He hunched over his animation desk, squinted his eyes, and drew.6

“The artists in the cartoon industry at last have a Union!” read the March bulletin from the Screen Cartoonists Guild. “Because the industry is young, the artists who compose it have lagged behind, rather than kept pace with the organization of the employees in the other fields of motion picture entertainment. The actors, the writers, the publicists, etc., have long been organized. We were the last!”7

At the following general-membership Guild meeting on Monday, March 3, announcements were made: the Labor Relations Board had said that it would take six to nine months to complete its investigation on whether the Federation was company dominated. What’s more, the Guild had the rightful claim to the majority of eligible employees, since the Federation’s tally wrongfully included employees not eligible, such as supervising animators and directors. The Disney unit put the boycott resolution to a vote and unanimously decided to place the studio on the Unfair/Do Not Patronize list if the studio refused a cross-check. This cross-check would tally Disney’s total artists against the Guild’s list of Disney artists, to confirm if the Guild had the majority.8

The cross-check had to be conducted by an impartial third party. Lessing agreed to a cross-check under the condition that the “impartial third party” was the Labor Relations Board. However, the Labor Relations Board was unavailable for six to nine months. “The NLRB has its hands tied,” protested the Guild, “It has a case pending before it now regarding the legality of [the Federation] and is therefore unable to be impartial.”9

Meanwhile, accusations of being a Communist continued to bombard Sorrell. He was prepared to extricate himself from negotiations and resign from the Painters Union altogether, but the union voted to reject his resignation.

Sorrell stayed on, much to the relief of the Guild members. But the allegation was a blemish that would only fester with time.

While the battle raged between the Guild and the Federation, the studio put eyes on its artists. At a meeting with Personnel, Walt discussed designating “efficiency experts” to curb expenses. He suspected Babbitt of earning more bonuses than he deserved. “There might be an animator, like Babbitt, who is getting more work because he hasn’t properly completed the work going to [his] clean-up [assistants],” he told them, “and still, we have the problem of keeping him busy. This plan of ours will stop the racketeers.”10 Whether true or not, suspicion of animators exploiting the bonus system permeated the studio.11

Two men from Personnel, including Hal Adelquist, became the efficiency experts and began patrolling the corridors. They popped in and out of rooms to reinforce the new “speed up” order for employees to obey. As one of the more loyal artists remembered, they were “on a scouting expedition throughout the studio to report to [Walt] any information they could glean and also report any infractions of working rules.” These rules forbade any union talk on company property or company time. “Whenever those two men . . . came into our rooms, we ‘clammed up.’”12

Certain animators (including Les Clark and Fred Moore) complained to Adelquist that Babbitt had been spending a lot of time in their room talking about the Guild. On March 12, Adelquist summoned Babbitt to his office for a meeting. His secretary kept stenographic notes.

“A few complaints regarding you personally have come to my attention,” said Adelquist. “I want to refer you again to Walt’s memo to please carry on union activities either at lunchtime or after five-thirty. It has come up that you have been going through the unit, talking to the fellows—”

“They’ll have to prove that,” said Babbitt.

“There’s no intention to prove anything, Art,” said Adelquist.

“When I go to the coffee shop,” said Babbitt, “if I talk to anybody, I do it there. People on both sides are guilty. [Animator] Dan MacManus can tell you that he took one and a half hours of my time last week. Yesterday [animator] Berny Wolf came in and spent almost an hour with me.”

“I’ll want to call all those boys and remind them of Walt’s memo,” said Adelquist. “I’m not taking sides, only complaints have come to me that you personally have been going into the rooms and talking to the boys during working hours.”

“Yes, I’ve done that,” said Babbitt. “I don’t deny it. But when I go into a room, like Bill Tytla—I see him every day—I never stay more than five minutes. Same with Les Clark.”

“You understand what I mean,” said Adelquist.

“Both Bodle and Yager in the Labor Board have cautioned me, so I have been extremely careful,” said Babbitt.

“If the boys do drop into your room during company time, I would appreciate your telling them to make it after business hours,” said Adelquist. “We are in such a condition right now that the thing we need is production. We need it so badly that if we don’t get it, there won’t be any unions. The more time you take away from the man who should be contributing work is bad. We don’t want to discontinue the coffee shop and those privileges, but if we don’t get out the work, we’re going to have to. If it were someone else from the other union, I would tell him the same thing and ask him to be fair and honest about it.”

“I have no excuse for myself,” said Babbitt, “but I am more or less in the position where I am under scrutiny by everybody. Everyone who is not on my side is bound to criticize me.”

“If you fellows, on your respective sides, could only agree that the working time here at the studio should be consumed in working—and any other discussions should be after hours,” said Adelquist. “What I wanted to talk to you about was that I’d appreciate you fellows cooperating with Walt. That’s the one thing he asked for . . . for the men to give him a fair deal. He doesn’t care what happens off the lot.”

“I’m inclined to believe he doesn’t give a damn what happens off the lot,” Babbitt retorted.

The discourse intensified and for a minute the secretary lost track. Adelquist addressed Babbitt’s belated delivery of his Mr. Stork scenes, linking the delay to the hours Babbitt spent talking to colleagues and making flyers. Babbitt argued that it took longer because he was striving for quality.

Adelquist de-escalated the conversation. “There have been complaints that you personally have solicited for unions during company hours and have been taking other people’s time,” he said.

“That’s true.”

“I just wanted to caution you about it,” said Adelquist. “I’m only asking for your sense of fair play on the thing. If fellows do come in to your room to ask questions, tell them you are busy but would be happy to talk to them on your own time. I’d tell the same thing to the opposing interest.”13

This closing statement was Adelquist’s attempt to appear fair and transparent. But his actions increasingly demonstrated something else—that he would do whatever it took to curry Walt’s favor.

Babbitt, in an attempt to placate his ex-groomsman, posted a sign on his office door reading, DO NOT DISTURB; IF YOU WANT INFORMATION ATTEND TONIGHT’S MEETING.14

That month, the Guild gained the support of the Central Labor Council of the San Fernando Valley. At the following Guild meeting on Monday, March 10, more than 400 attendees witnessed the induction of 150 animation artists, most of whom were from Disney.15 The Guild began sponsoring twice-weekly sketch classes, as well as talks by California’s deputy labor commissioner.16

For unknown reasons, Babbitt started bringing a loaded .22-caliber pistol to work at this time. Known as a “plinking gun,” this model is often used for target practice, such as the skeet-shooting that Babbitt had done in the California desert. Babbitt used it as an overt intimidation tactic—an apparent move out of Sorrell’s playbook. He kept the gun in the top drawer of his animation desk, barely covered with a piece of paper. He didn’t hesitate to open the drawer and gauge others’ reactions.

Unsurprisingly, this did not go over well. On the morning of March 22 the Burbank police charged Babbitt with carrying a loaded weapon without a permit. While in jail (with bail set at $200), “one of the girls” from the Guild brought him an apple—a token of support from the hundreds he represented. He pleaded guilty, his thirty-day sentence was suspended, and he was placed on parole.17

Meanwhile, Walt Disney Productions was desperately searching for ways to stay afloat. On Friday, March 21, Disney’s Airbrush Department was discontinued. Those artists were offered a one-month tryout in the Ink & Paint Department—which incensed many, since Ink & Paint tryouts had always been three months. A conference was held on Saturday between Gunther Lessing and AFL leaders Blair, Bodle, and Sorrell. Negotiations took place, to no avail. The conference would not be the last, though that day would be the Disney studio’s last working Saturday.

That following Monday, March 24, Roy Disney called a five o’clock meeting for the key artists from the Layout, Background, Direction, and Animation Departments. Some months before, unions had successfully pushed the US government to regulate a five-day workweek through the new Wages and Hours Act. Roy outlined a forty-hour, five-day workweek for all employees who were considered nonspecialists. To save the studio money, Roy announced salary cuts across the board and an elimination of luxury items. He asked that people start work punctually at 8:30 and put in an honest eight hours every day. Director Dave Hand suggested posting an oversized thermometer on the wall gauging the film footage progress.

Babbitt accepted the standard 15 percent pay cut for high earners, from $200 a week to $170.18 Everyone signed an acknowledgment of their salary cut with a percentage proportionate to their wages. “God damn,” Fred Moore protested, “why don’t they weed out the dead wood!”19 The term dead wood began circulating more among the non-Guild employees. Ever since the hiring spree for Snow White, many newer low-level artists were seen as weighing down the studio. They had circumvented the arduous tryout period and were considered lazy and complacent.

To decide which craftworkers in Hollywood qualified for the forty-hour workweek, a Wages and Hours Act hearing was held on March 25. Hollywood studio managers argued against representatives of fourteen Hollywood unions. The Screen Cartoonists Guild was included among the unions that argued for its workers’ rights. The Federation was suspiciously absent.20

On Monday, March 31, four Guild committee members met with Gunther Lessing to voice grievances. These concerned the treatment of the ex-airbrush artists, unfair salary cuts for inkers and inbetweeners, and nine effects animators slated for layoffs who wanted a trial period in character animation. Lessing asked that the complaints be presented in written form, and the Guild members did so. Lessing then required that the Guild resolve this with O’Rourke and his impartial machine. When asked who in the impartial machine would cast the deciding vote, it was revealed that it was O’Rourke himself, a management employee. The Guild, aghast, canceled the meeting.

The artists weren’t the only thorns in Lessing’s side; the Editing Department was also fed up with prolonged contract negotiation. Its union, the Society of Motion Picture Film Editors, had been certified for nearly two years. On March 27 the union had filed an unfair charge against the company, along with other unions that Walt Disney Productions failed to recognize: the Transportation Drivers Union, the Studio Plasterers, and the Film Technicians/Laboratory Workers. They all aligned with the Screen Cartoonists Guild, their union leaders working in tandem, and with the American Federation of Labor (AFL) representing them all.21

On the night of Tuesday, April 1, the AFL prepared to lead hundreds of Disney employees to go on strike in a week’s time. The news made the front page of Variety. The Guilders said that Gunther Lessing had refused to meet or even answer their telephone calls. Walt’s own supporters pressed Walt to bring in a more experienced conciliator or even lead negotiations himself.22

On Wednesday, April 2, Lessing agreed to negotiate with the various union leaders of the AFL. He explained that the delay was a big misunderstanding and that he desired to follow the same protocol as the other studios. At this, the Labor Relations Board stepped in and called an “armistice,” averting the planned strike. Lessing subsequently issued a memo to all Disney studio personnel, falsely reporting that “there has been no evidence received by the Disney management to support the gossip about a strike.”23

While Blair, Bodle, and Sorrell prepared to confer with Lessing, the Disney vice president didn’t waste time. A few days later, fifteen studio security guards were deputized as members of the Burbank police force at City Hall. The maneuver, not uncommon in Hollywood, gave Disney guards the legal authority to use force and make arrests.24

Lessing, accompanied by Herb Lamb, met with AFL and Guild union reps on Wednesday, April 9, and Friday, April 11. Lessing advocated for an election, all the while flaunting his experience at Herb Sorrell. “He would say he was the legal counsel for Pancho Villa,” said Sorrell, “and I’d say, ‘Pancho Villa never won anything legal in his life.’” Infuriated by Lessing’s inflexibility, the AFL rescheduled its labor strike for the following week.25

On Tuesday, April 15, Lessing requested more time to consider the union demands. The AFL complied and agreed on a temporary “truce.” Lessing had a new strategy: buy time for the Federation to assure its legitimacy. That Friday, the Federation strengthened its platform by electing a new board of officers.

Walt joined the meeting with the AFL on Monday, April 21. Herb Sorrell brought a stack of Guild membership cards, claiming to have the majority needed, and demanded that Walt sign a union contract. “I told Mr. Sorrell that there is only one way for me to go and that was an election,” recounted Walt six years later. “And that is what the law had set up—the National Labor Relations Board was for that purpose. He laughed at me and he said that he would use the Labor Board as it suited his purposes. . . . I told him that it was a matter of principle with me, that I couldn’t go on working with my boys feeling that I had sold them down the river to him on his say-so, and he laughed at me and told me I was naïve and foolish.”26

Sorrell challenged Walt to make a deal or he would turn the studio into “a hospital filled with workers beaten in a union war.”27 He said, “This could be turned into a nice hospital or dust bowl.”28 The threat of razing the studio to a dust bowl crossed the line. The meeting was a bust.

Lessing then appeared to step aside as Disney’s union negotiator, replaced with an experienced labor attorney named Walter P. Spreckels. Spreckels was the regional director of the Labor Relations Board in Los Angeles, but now that he was Disney’s labor negotiator, his seat at the board was filled by longtime labor specialist William Walsh.

While Spreckels scheduled his first conference with the negotiation team of Blair, Bodle, and Sorrell (for Monday, April 28), Walsh tackled the Disney issue from the local Labor Relations Board office. Walsh no doubt remembered Babbitt from 1937, when Babbitt had consulted with Walsh during the Federation’s founding, and Walsh had given Babbitt a list of labor attorneys. Now Walsh addressed the February complaint against the Federation’s legitimacy. Instead of waiting for a formal hearing in Washington, Walsh called for an immediate conference—a local, unofficial hearing in his Los Angeles offices.

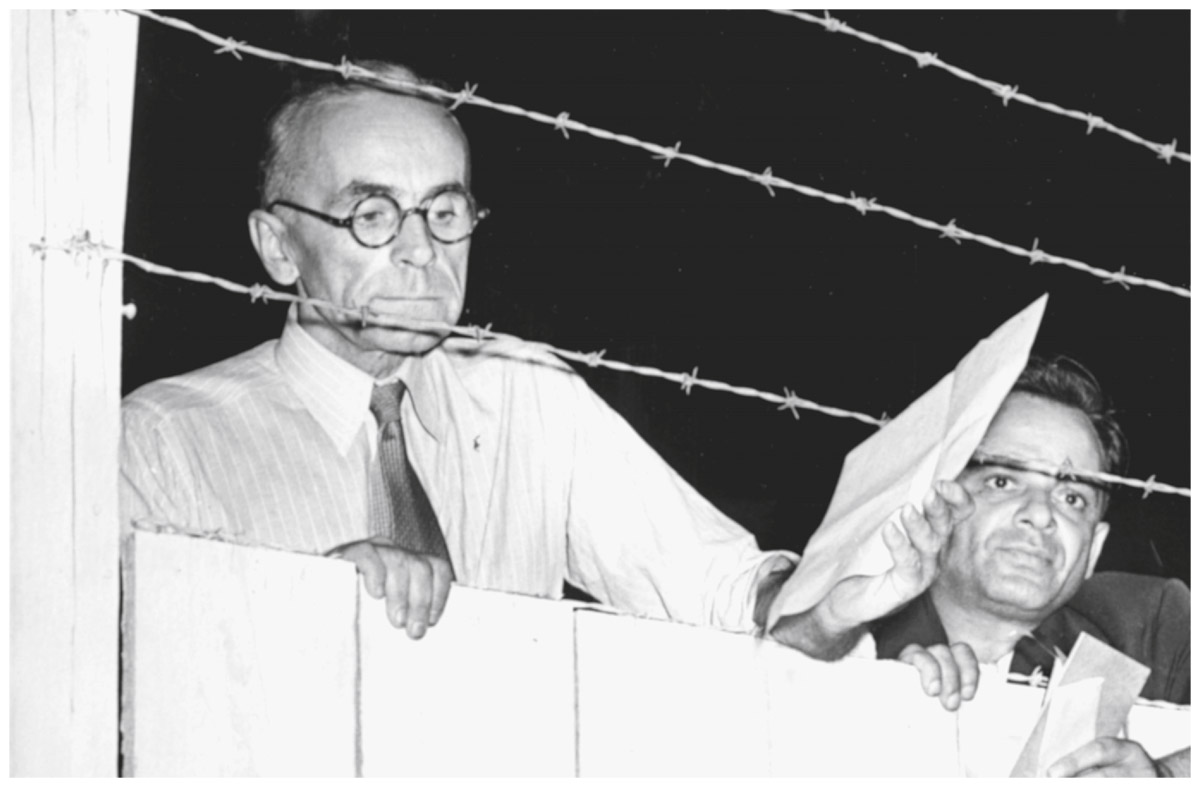

Walter Spreckels (left) in 1939, sharing the results of a unionization ballot at Gilmore Stadium, Hollywood.

The conference was held on April 29 at 1:30 PM. Gunther Lessing and Federation attorney Howard Painter stated their case against Herb Sorrell and Art Babbitt, referencing Sorrell’s “dust bowl” threat. Lessing and Painter had far more legal experience than their opposition, but Babbitt’s testimony tipped the scales. Specifically, Walsh ruled that because the Federation was codeveloped by management, it could never be independent, “and much of the responsibility for this must be laid at the door of Gunther Lessing.”29 Walsh ruled that the Federation was indeed company-dominated and therefore illegitimate.

Painter and Lessing leapt from their chairs, calling the Guild members “white-livered cowards.” Painter demanded that Walsh consider the newly elected Federation board. Instead, Walsh recommended that the Federation disband voluntarily, saying he had no doubt that Washington would agree with his ruling.30

At the studio the next day, Dave Hilberman waved the latest edition of Variety, which reported the conference, and shouted the news.31 Babbitt spent lunchtime gloating, walking through the studio campus warmly greeting his fellow Guild members. In his office, Walt wired each Labor Relations Board member in Washington requesting a hearing as soon as possible.32

The Federation stubbornly refused to concede. On May 1 a Federation bulletin appeared on the boards with the headline BUT MR. BABBITT, WE DON’T FEEL COMPANY DOMINATED!33 To combat any doubt, the next morning, Guilders distributed handbills outlining the events of the conference. This infuriated Howard Painter. He circulated a two-page bulletin that same day, invalidating the decision and scorning Babbitt in all caps. He wrote, “THE VERY OFFICER TO WHOM WAS INTRUSTED THE WELFARE OF THE FEDERATION NOW CONTENDS THAT THE FEDERATION WAS DOMINATED BY THE COMPANY.”34 The bulletin concluded that the matter would be taken to the federal level.

It wasn’t an empty threat; Walt announced that if a strike was called and “any violence occurs,” he would close the studio.35 It is telling that Walt automatically named violence among labor tactics. He had become conditioned to fear unionists. Just as Babbitt’s opinions had become extreme, so had Walt’s. Top attorneys at Walt’s company—Gunther Lessing, Anthony O’Rourke, and Howard Painter—blamed the discord on Babbitt. As Babbitt described in 1942, Walt confronted Babbitt in the corridor of the main animation building and said that if Babbitt didn’t stop organizing his employees, he would throw Babbitt “right the hell out of the front gate.”36

This exchange, if true, was oddly prophetic. That is exactly what the studio did.