24 The Final Strike Vote

AROUND MAY 3, 1941, three days after Walt’s first request for a hearing, the National Labor Relations Board responded and set a hearing for May 19. Walt took a brief vacation and left his lawyers to sort the rest out.

The Disney employees had diverged into warring factions. Disney labor relations consultant Walter Spreckels circulated a page-long bulletin on Monday, May 5, acknowledging the divisiveness at the studio and summarizing the upcoming hearing. “If the Board finds the Federation to be a legitimate labor organization, you may be required to express your choice between the Guild (A. F. of L.) or the Federation; if the Board finds against the Federation you may be required to vote for or against the Guild. Whichever way the Labor Board rules, Walt will abide by the law.”1

There was still a lot of work to be done at the studio. After delays, The Reluctant Dragon was set to release on June 6, but poor Dumbo still had a ways to go. Although 90 percent of Dumbo’s animation was complete, only 30 percent of its cels were inked and painted, and just 10 percent of those cels had been photographed. Dumbo’s August 15 release would add much needed revenue, if the studio could finish it in time. Bambi was also expected to be released in early fall, and the “Mickey Feature” around Christmas.2 (Eventually all of these would be exponentially delayed—The Reluctant Dragon until late June, Dumbo until October, Bambi until 1942, and the “Mickey Feature,” as part of Fun and Fancy Free, until 1947.)

The studio received a paltry bump in its finances on May 8, when it sold the old Hyperion Avenue studio for $75,000.3 The birthplace of all Disney animation from Mickey and Minnie Mouse to Snow White would henceforth be a thing of the past.

On Friday, May 9, at 9:15 AM, Blair, Bodle, Sorrell, and Babbitt met with Spreckels at Herb Lamb’s request. They discussed the possibility of a Guild grievance committee. No agreement was reached at the meeting, and so the AFL again called a strike for the following week. The threat worked. Over the weekend, Spreckels met with Blair, Bodle, and Sorrell and agreed to meet with a grievance committee, but pending the upcoming hearing. The strike was averted. Sorrell was impressed with Spreckels’s fairness and credited him with being the sole reason the strike threat was cancelled. He said that it would be easy to reach a final agreement as long as Spreckels continued to handle the negotiations.4

That week, when Walt returned from his vacation, things began to change. On Thursday, May 15, the Federation circulated its final bulletin. “The certification from the NLRB outlived its usefulness as we knew it would one day,” it read. “And so—fellow members, the Federation passes into oblivion.”5

That day, without warning, Disney management reneged on Spreckels’s earlier deal to recognize a grievance committee.6 This flip was a shock to the Guild, which made a plea for the studio remain neutral and to report any negotiation interference to Spreckels. However, Spreckels’s role had become strictly ornamental.

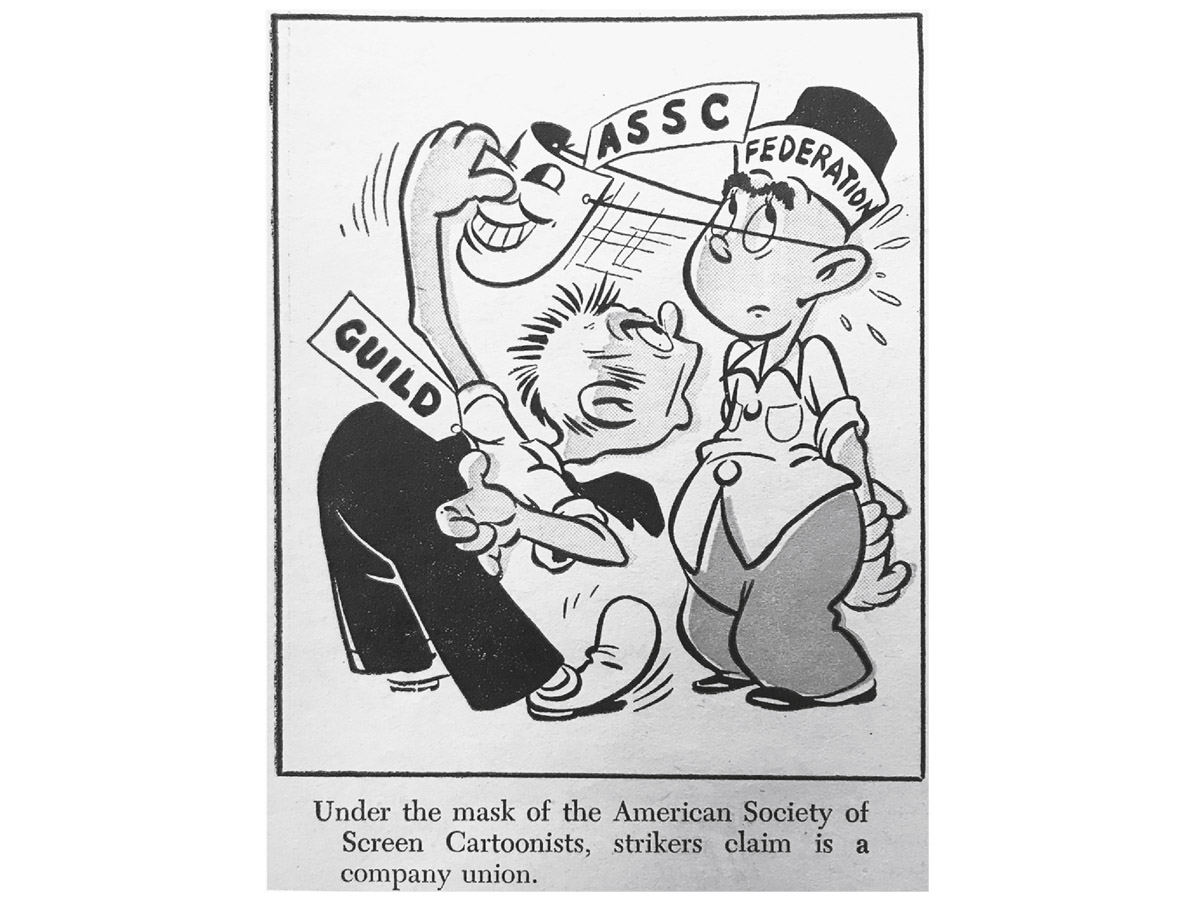

The next day a new bulletin appeared. “Today marks the introduction of a new Union for the employees of Walt Disney Studio,” it read. “Its name is the American Society of Screen Cartoonists . . . ASSC has a clean slate . . . JOIN TODAY.” The names of the chairpersons, as well as the PO box, were the same as the Federation’s.7

A labor crisis suddenly struck the Warner Bros. animation studio. The AFL had been in negotiations with animation producer Leon Schlesinger for weeks. Schlesinger, overweight in a tight suit and curly toupee, normally led his animators with good-natured laissez-faire. He was a businessman, not an artist, and his creative direction was little more than saying, “Put a lot of jokes in it.”8

Over the weekend of May 17–18, the Guild’s Warner Bros. unit (led by Chuck Jones) made Schlesinger an ultimatum: sign a union contract now or suffer a strike on Monday. Rather than complying, Schlesinger issued a lockout. On Monday May 19, his 185 workers arrived at the door to see a sign reading STUDIO CLOSED ON ACCOUNT OF STRIKE. That afternoon, Schlesinger met with Herb Sorrell, Chuck Jones, and the rest of the Warner Bros. cartoonists’ negotiating committee. “We tried very hard to make a deal with Mr. Schlesinger and we offered him the same deal we had with MGM,” said Sorrell. “Schlesinger did not comply.”9 That evening, at the behest of the AFL, the Los Angeles Central Labor Council placed Schlesinger’s studio on the Unfair/Do Not Patronize list.10

A drawing by an anonymous Disney striker depicting how the new Disney union, the ASSC, was just a rebranding of the previous company union, the Federation of Screen Cartoonists.

The lockout went into a second day. On Tuesday evening, Sorrell and Schlesinger met again. Schlesinger complained that the Guild was financially killing him. Sorrell told Schlesinger, “Raise the price to Warner Brothers. They have to pay it.” Schlesinger looked at the contract again—and pointed out that the agreement was for $2,600 more than it was two days before. Sorrell explained that each day, he was increasing the demands for all the lowest-paid staff, “and it would cost him $1,300 a day for every day he prolonged the opening.” Schlesinger grabbed the contract with a “give me that” and signed.

“Now,” said Schlesinger, “what about Disney?”11

The Disney hearing took place as scheduled on May 19. At the local Labor Relations Board office, a trial examiner from Washington presided over Walt Disney Productions and the Screen Cartoonists Guild. Gunther Lessing, not Spreckels, represented the company.

Lessing produced pamphlets stating that the Federation had disbanded, therefore the Labor Relations Board was “trying a dead body.” The trial examiner reminded Lessing that the “body” being tried was Walt Disney Productions, not the Federation, and that if Lessing confused them, then the two couldn’t be far apart after all.

Lessing agreed to a consent decree (a settlement without any admission of guilt), and the hearing was adjourned.12

Suddenly, on May 20, roughly twenty-four Disney artists received an ominous memo. Due to “circumstances beyond the control of this studio . . . your release is effective as of 5:30 PM this afternoon.” Attached were two weeks’ salary in lieu of notice. Walt met with the group in his office, explaining that the layoff was an unfortunate side effect of world conditions and offering them letters of recommendation.13 The artists glanced at one another. Of the people laid off that day, seventeen were Guild members, including five Guild officials. It was certain that the Personnel Department had cherry-picked them to be terminated. The non-Guilders had informed Personnel whenever an artist was spotted at a Guild meeting.14

The Disney animators—Guild members and not—called the mass firing a “Blitzkrieg.”15 The timing was inordinately suspicious. Due to the layoff, the population of Guild members at the studio now possibly inched below half, though Lessing denied any discrimination.16 Rumors of another mass layoff began to spread, and Disney artists began to suspect that the axe would fall on “Babbitt and his Guild followers.”17

A day or two later, Babbitt led a lunch meeting in the studio animation building. It was an introduction to the Guild for the tyros working as apprentices and in the Traffic Department (i.e., messenger boys). Hal Adelquist got wind of the meeting and informed Gunther Lessing. Lessing interrogated four of the youths, asking to identify those in attendance. They refused to name names.

The union election was also imminent. Walt Disney released a statement on Thursday, May 22. “My employees . . . are free to join any organization, and we will bargain collectively with the union or organization so chosen.”18 On the same document, Disney’s new publicity manager claimed that the ASSC now had the majority of artists. Guild members objected that a member of management was speaking on behalf of the ASSC.

That night, at an emergency meeting at the Roosevelt Hotel, the Guild voiced its complaints. Its members felt that the creation of the ASSC was a signal that Disney had broken faith with them—that despite the Guild’s many concessions postponing its strike threats, the company had only been stalling.19

Bill Hurtz was now a Guild officer alongside Babbitt. He remembered, “Art got me to one side and said, ‘When I nod at you, get up and make a motion to strike.’” He did, and the motion passed. They would schedule a strike vote for May 28 if Walt refused to meet with them.20

Guild president Bill Littlejohn wired Walt Disney: “The union committee was instructed unanimously to meet with you personally on Monday, May 26, for the purpose of obtaining recognition. . . . Failure to grant a meeting will result in recommendation that the union take action to protect the interests of its members.”21

In his office, Walt was coordinating the June 6 release of The Reluctant Dragon, the production of Bambi, and the completion of Dumbo. He was making plans for a grand research trip to Latin America. He replied that he was too busy to meet.22

On Monday night, in the Blossom Room of the Roosevelt Hotel, the Disney Guilders voted 315 to 4 to strike. The six hundred Guild members voted unanimously to approve the strike, set for 6:00 AM Wednesday, May 28. The Guild immediately appointed different committees to handle the details, including publicity, pickets, and office. The Guild also announced that the Los Angeles Central Labor Council would meet on Tuesday afternoon to move forward with a national Disney boycott.

Late Tuesday morning, Walt again addressed his entire staff in the studio theater: “I believe it only fair to tell our employees that in the event of a strike the studio will remain open. . . . I desire that it be made plain to all my employees that they are free to join any union which they may select or prefer. We always have been ready, are now ready, and always will be ready to bargain collectively with any appropriate bargaining unit designated by a majority of the employees by secret ballot in an election held for that purpose. I’m sorry,” Walt concluded, “that’s all that I can say. Thanks.”23 Walt left the theater to a tremendous ovation.24

Babbitt was not at the meeting. As he exited the studio restaurant, the chief of studio police took hold of his arm and handed him an envelope, telling him it was bad news.25 The envelope contained two notices on Disney studio letterhead. The first stated that conducting union activities on company time and property “disturbed the morale of the employees and has seriously interrupted and disturbed production operations,” thereby violating his employment contract.26

The second letter was a single paragraph: “Walt Disney Productions . . . hereby terminates all of your right, title, and interest in said contract and terminates your employment thereunder forthwith.” It was signed “Gunther Lessing, Vice President.”27 Babbitt was to clear out immediately.

Babbitt was granted permission to pack his things and load his car in front of the animation building. The chief and another officer flanked him. With slow and deliberate showmanship, Babbitt loaded his car as the mass of Disney employees left Walt’s meeting from the theater directly opposite the animation building. Babbitt shouted that he had been fired. Some helped him load his car, and others called out that they would see him on the picket line the next day.28

As Babbitt drove off, he called out, “I’ll be back!” People who had applauded Walt minutes before now cheered for Babbitt. Some inkers sobbed. Fred Moore began running around in a panic.

Bill Tytla paced the building’s steps with a worried look on his face.29 He had found his calling at the Disney studio, but he had joined the Guild to support Babbitt. Like it or not, the line in the sand had been drawn.