Book One

A Few Pages of History

I

Well-tailored

THE YEARS 1831 and 1832, immediately succeeding the July Revolution, are among the most singular and striking in our history. These two years, in the setting of those that preceded and those that followed them, are like two mountains displaying the heights of revolution and also its precipitous depths. The social masses which are the base of civilization, the solid structure of superimposed and related interests, the secular outlines of France’s ancient culture, all these constantly appear and disappear amid the storm-clouds of systems, passions and theories. These appearances and disappearances have been termed movement and resistance. At intervals one may catch a gleam of Truth, that daylight of the human soul.

This remarkable period is sufficiently distinct, and now sufficiently remote from us, for its main outlines to be discernible. We shall seek to depict them.

The Bourbon restoration had been one of those intermediate phases, difficult of definition, in which exhaustion and rumour, mutterings, slumber and tumult all are mingled, and which in fact denote the arrival of a great nation at a staging-point. Such periods are deceptive and baffle the policies of those seeking to exploit them. At the beginning the nation asks for nothing but repose; it has only one desire, which is for peace, and one aspiration, which is to be insignificant. In other words, it longs for tranquillity. We have had enough of great happenings, great risks, great adventures, and more than enough, God save us, of great men. We would exchange Caesar for Prusias and Napoleon for the Roi d’Yvetot – ‘what a good little king he was’, as Béranger sang. The march has gone on since dawn, and we are in the evening of a long, hard day. The first stage was with Mirabeau, the second with Robespierre and the third with Bonaparte. Now we are exhausted and each man seeks his bed.

What do they so urgently look for, the wearied devotions, the tired heroisms, the sated ambitions, the fortunes gained? They want a breathing-spell, and they have one. They take hold of peace tranquillity, and leisure, and are content. Yet certain facts emerge and call for notice by hammering on the door. They are facts born of revolution and war, living and breathing facts entitled to become part of the fabric of society, and which do so. But for the most part they are the under-officers and outriders whose business is to prepare lodgings for the commanders.

It is now that the political philosophers appear on the scene, while the weary demand rest and new-found facts demand guarantees. Guarantees are to facts what rest is to men.

That is what England demanded of the Stuarts after the Protector and what France demanded of the Bourbons after the Empire.

These guarantees are a necessity of the time. They have to be conceded. The princes ‘offer’, but it is the force of events that gives. This is a profound truth, necessary to know, which the Stuarts did not appreciate in 1660 and of which the Bourbons had not an inkling in 1814.

The predestined family which returned to France after the collapse of Napoleon was sufficiently naïve to believe that it was giving, and that what it had given it might take back; that the House of Bourbon possessed divine rights and that France possessed none; that the political concessions granted in the charter of Louis XVIII were no more than blossomings of the Divine Right, plucked by the House of Bourbon and graciously bestowed on the people until such time as it might please the king to reclaim them. But its very reluctance to concede them should have warned the House of Bourbon that the gift was not its own.

The Royal House was acrimonious in the nineteenth century. It pulled a wry face at every advance of the nation. To use a trivial word – that is to say, a commonplace and true one – it jibbed. The people saw this.

The Bourbons believed that they were strong because the Empire had been swept away before them like the changing of a stage-set. They did not perceive that they had been brought back in the same fashion. They did not see that they too were in the hands that had removed Napoleon.

They believed they had roots because they represented the past. They were wrong. They were a part of the past, but the whole past was France. The roots of French society were not in the Bourbons but in the nation. Those deep and vigorous roots were not the rights of a single family but the history of a people. They were everywhere, except under the throne.

The House of Bourbon was the illustrious and blood-stained core of France’s history, but it was no longer the principal element in her destiny or the essential basis of her policies. The Bourbons were dispensable, they had been dispensed with for twenty-two years, the continuity had been broken. These were things they did not realize. How could they be expected to realize them, maintaining as they did that the events of 9 Thermidor had occurred in the reign of Louis XVII, and Marengo in the reign of Louis XVIII? Never since the beginning of history have princes been so blind in the face of facts, so unaware of the portion of Divine Authority which those facts embraced and enacted. Never has the earthly pretension which is called the right of kings so flatly denied the Right which comes from above.

It was a fatal blunder which prompted this family to lay hands on the guarantees ‘offered’ in 1814 – concessions, as they described them. A sad business. Those so-called concessions were our conquests, and what they called our encroachments were our rights.

When it thought the time was ripe, the Restoration, believing itself victorious over Bonaparte and enrooted in the nation – that is to say, believing itself to be both strong and deep – abruptly showed its face and chanced its arm. On a July morning it confronted France and, raising its voice, revoked both collective and individual rights, the sovereignty of the nation and the liberty of the citizen. In other words it denied to the nation that which made the nation, and to the citizen that which made the citizen.

This was the essence of those famous Acts which are called the Ordonnances de juillet.

The Restoration fell.

It was right that it should fall. Nevertheless it must be said that it had not been absolutely hostile to all forms of progress. Great things had been accomplished while the regime looked on.

Under the Restoration the nation had grown accustomed to calm discussion, which had not happened under the Republic, and to greatness in peace, which had not happened under the Empire. A free and strong France had provided a heartening example for the peoples of Europe. Revolution had spoken under Robespierre, and guns had spoken under Bonaparte: it was under Louis XVIII and Charles X that intellect made itself heard. The winds died down and the torch was re-lighted. The pure light of the spirit could be seen trembling on the serene heights, a glowing spectacle of use and delight. During a period of fifteen years great principles, long-familiar to the philosopher but novel to the statesman, were seen to be at work in peace and in the light of day: equality before the law, freedom of conscience, freedom of speech and of the press, careers open to all talents. So it was until 1830. The Bourbons were an instrument of civilization which broke in the hands of Providence.

The fall of the Bourbons was clothed with greatness, not on their side but on the side of the nation. They abandoned the throne solemnly but without authority. This descent into oblivion was not one of those grave occasions which linger as a sombre passage of history; it was enriched neither with the spectral calm of Charles I nor with the eagle-cry of Napoleon. They went away, and that was all. In putting off the crown they retained no lustre. They were dignified but not august, and in some degree they lacked the majesty of their misfortune. Charles X, causing a round table to be sawn square during the voyage from Cherbourg, seemed more concerned with the affront to etiquette than with the crumbling of the monarchy. This narrowness was saddening to the devoted men who loved their persons and the serious men who honoured their race. The people, on the other hand, were admirable. The nation, assailed with armed force by a sort of royal insurrection, was so conscious of its strength that it felt no anger. It defended its rights and, acting with restraint, put things in their proper place (the government within the law, the Bourbons, alas, in exile) and there it stopped. It removed the elderly king, Charles X, from under the canopy which had sheltered Louis XIV, and set him gently upon earth. It laid no hand on the royal persons except with sorrow and precaution. This was not the work of one man or of several men; it was the work of France, the whole of France; victorious France flushed with her victory who yet seemed to recall the words spoken by William of Vair after the Day of the Barricades in 1588: ‘It is easy for those accustomed to hang upon the favours of the great, hopping, like birds on a tree, from evil to good fortune, to be bold in defying their prince in his adversity; but for myself, the fortunes of my kings will always be deserving of reverence, and especially in their affliction.’

The Bourbons took with them respect but not regret. As we have said, their misfortune was greater than themselves. They vanished from the scene.

The July Revolution at once found friends and enemies throughout the world. The former greeted it with enthusiasm and rejoicing, the latter averted their gaze, each according to his nature. The princes of Europe, like owls in the dawn, at first shut their eyes in wounded amazement, and opened them only to utter threats. Their fear was understandable, their wrath excusable. That strange revolution had been scarcely a conflict; it had not even done royalty the honour of treating it as an enemy and shedding its blood. In the eyes of despotism, always anxious for liberty to defame itself by its own acts, the grave defect of the July Revolution was that it was both formidable and gentle. And so nothing could be attempted or plotted against it. Even those who were most outraged, most wrathful, and most apprehensive, were obliged to salute it. However great our egotism and our anger, a mysterious respect is engendered by events in which we feel the working of a power higher than man.

The July Revolution was the triumph of Right over Fact, a thing of splendour. Right overthrowing the accepted Fact. Hence the brilliance of the July Revolution, and its clemency. Right triumphant has no need of violence. Right is justice and truth.

It is the quality of Right that it remains eternally beautiful and unsullied. However necessary Fact may appear to be, however acquiesced in at a given time, if it exists as Fact alone, embodying too little Right or none at all, it must inevitably, with the passing of time, become distorted and unnatural, even monstrous. If we wish to measure the degree of ugliness by which Fact can be overtaken, seen in the perspective of centuries, we have only to consider Machiavelli. Machiavelli was not an evil genius, a demon, or a wretched and cowardly writer; he was simply Fact. And not merely Italian Fact but European Fact, sixteenth-century Fact. Nevertheless he appears hideous, and is so, in the light of nineteenth-century morality.

The conflict between Right and Fact goes back to the dawn of human society. To bring it to an end, uniting the pure thought with human reality, peacefully causing Right to pervade Fact and Fact to be embedded in Right, this is the task of wise men.

II

Badly stitched

But the work of the wise is one thing and the work of the merely clever is another.

The revolution of 1830 soon came to a stop.

Directly a revolution has run aground the clever tear its wreckage apart.

The clever, in our century, have chosen to designate themselves statesmen, so much so that the word has come into common use. But we have to remember that where there is only cleverness there is necessarily narrowness. To say, ‘the clever ones’ is to say, ‘the mediocrities’; and in the same way to talk of ‘statesmen’ is sometimes to talk of betrayers.

If we are to believe the clever ones, revolutions such as the July Revolution are like severed arteries requiring instant ligature. Rights too loudly proclaimed become unsettling; and so, once righteousness has prevailed, the State must be strengthened. Liberty being safeguarded, power must be consolidated. Thus far the Wise do not quarrel with the Clever, but they begin to have misgivings. Two questions arise. In the first place, what is power? And secondly, where does it come from? The clever ones do not seem to hear these murmurs and continue their operations.

According to these politicians, who are apt at dissembling convenient myths under the guise of necessity, the first thing a nation needs after a revolution, if that nation forms part of a monarchic continent, is a ruling dynasty. Only then, they maintain, can peace be restored after a revolution – that is to say, time for the wounds to heal and the house to be repaired. The dynasty hides the scaffolding and affords cover for the ambulance.

But it is not always easy to create a dynasty. At a pinch any man of genius or even any soldier of fortune may be made into a king. Bonaparte is an instance of the first, and an instance of the second is Iturbide, the Mexican general who was proclaimed emperor in 1821, deposed in 1823, and shot the following year. But not any family can be established as a dynasty. For this some depth of ancestry is needed: the wrinkles of centuries cannot be improvised.

If we consider the matter from the point of view of a ‘statesman’ (making, of course, all due reservations), what are the characteristics of the king who is thrown up by a revolution? He may be, and it is desirable that he should be, himself a revolutionary – that is to say, a man who has played a part in the revolution and in so doing has committed or distinguished himself; a man who has himself wielded the axe or the sword.

But what are the characteristics needful for a dynasty? It must represent the nation in the sense that it is revolutionary at one remove, not from having committed any positive act, but from its acceptance of the idea. It must be informed with the past and thus historic, and also with the future and thus sympathetic.

This explains why the first revolutions were content to find a man, a Cromwell or a Napoleon, and why succeeding revolutions were obliged to find a family, a House of Brunswick or a House of Orléans. Royal houses are something like those Indian fig-trees whose branches droop down to the earth, take root and themselves become fig-trees: every branch may grow into a dynasty – provided always that it reaches down to the people.

Such is the theory of the clever ones.

So the great art is this: to endow success with something of the aspect of disaster, so that those who profit by it are also alarmed by it; to season advance with misgivings, widen the curve of transition to the point of slowing down progress, denounce and decry extremism, cut corners and finger-nails, cushion the triumph, damp down the assertion of rights, swaddle the giant mass of the people in blankets and put it hastily to bed, subject the superabundance of health to a restricted diet, treat Hercules like a convalescent, fetter principle with expediency, slake the thirst for the ideal with a soothing tisane and, in a word, put a screen round revolution to ensure that it does not succeed too well.

This was the theory applied in France in 1830, having been applied in England in 1688.

1830 was a revolution arrested in mid-course, halfway to achieving real progress, a mock-assertion of rights. But logic ignores the more-or-less as absolutely as the sun ignores candlelight.

And who is it who checks revolutions in mid-course? It is the bourgeoisie.

Why? Because the bourgeoisie represent satisfied demands. Yesterday there was appetite; today there is abundance; tomorrow there will be surfeit. The phenomenon of 1814 after Napoleon was repeated in 1830 after Charles X.

The attempt has been made, mistakenly, to treat the bourgeoisie as though they were a class. They are simply the satisfied section of the populace. The bourgeois is the man who now has leisure to take his ease; but an armchair is not a caste. By being in too much of a hurry to sit back, one may hinder the progress of the whole human race. This has often been the failing of the bourgeoisie. But they cannot be regarded as a class because of this failing. Self-interest is not confined to any one division of the social order.

To be just even to self-interest, the state of affairs aspired to after the shock of 1830 by that part of the nation known as the bourgeoisie was not one of total inertia, which is composed of indifference and indolence and contains an element of shame; it was not a state of slumber, presupposing forgetfulness, a world lost in dreams; it was simply a halt.

The word ‘halt’ has a twofold, almost contradictory meaning. An army on the march, that is to say, in movement, is ordered to halt, that is to say, to rest. The halt is to enable it to recover its energies. It is a state of armed, open-eyed rest, guarded by sentinels, a pause between the battle of yesterday and the battle of tomorrow. It is an in-between time, such as the period between 1830 and 1848, and for the word ‘battle’ we may substitute the word ‘progress’.

So the bourgeoisie, like the statesmen, had need of a man who embodied the word ‘halt’. A combination of ‘although’ and ‘because’. A composite individual signifying both revolution and stability – in other words, affirming the present by formally reconciling the past with the future. And the man was there. He was Louis-Philippe of Orléans.

The vote of 221 deputies made Louis-Philippe king. Lafayette presided, extolling ‘the best of republics’. The Paris Hôtel de Ville replaced Rheims Cathedral. This substitution of a half-throne for an entire throne was ‘the achievement of 1830’.

When the clever ones had finished their work, the huge weakness of their solution became apparent. It had all been done without regard to the basic rights of the people. Absolute right cried out in protest; but then, an ominous thing, it withdrew into the shadows.

III

Louis-Philippe

Revolutions have vigorous arms and shrewd hands; they deal heavy blows but choose well. Even when unfinished, bastardized and doctored, reduced to the state of minor revolutions, like that of 1830, they still nearly always retain sufficient redeeming sanity not to come wholly to grief. A revolution is never an abdication.

But we must not overdo our praises; revolutions can go wrong, and grave mistakes have been made.

To return to 1830, it started on the right lines. In the establishment which restored order after the truncated revolution, the king himself was worth more than the institution of royalty. Louis-Philippe was an exceptional man.

The son of a father for whom history will surely find excuses, he was as deserving of esteem as his father was of blame. He was endowed with all the private and many of the public virtues. He was careful of his health, his fortune, his person and his personal affairs, conscious of the cost of a minute but not always of the price of a year. He was sober, steadfast, peaceable and patient, a friendly man and a good prince who slept only with his wife and kept lackeys in his palace whose business it was to display the conjugal bed to visitors, a necessary precaution in view of the flagrant illegitimacies that had occurred in the senior branch of the family. He knew every European language and also, which is less common, the language of every sectional interest, and spoke them all. An admirable representative of the ‘middle class’, he nevertheless rose above it and was in all respects superior to it, having the good sense, while very conscious of the royal blood in his veins, to value himself at his true worth, and very particular in the matter of his descent, declaring himself to be an Orléans and not a Bourbon. He was the loftiest of princes in the days when he was no more than a Serene Highness but became a franc bourgeois on the day he assumed the title of Majesty. Flowery of speech in public but concise in private; reportedly parsimonious, but this was not proved, and in fact he was one of those prudent persons who easily grow lavish where fancy or duty is involved; well-read but not very appreciative of literature; a gentleman but not a cavalier, simple, calm and strong-minded, adored by his family and his household; a fascinating talker; a statesman without illusions, inwardly cold, dominated by immediate necessity and always ruling by expediency, incapable of rancour or of gratitude, ruthless in exercising superiority over mediocrity, clever at frustrating by parliamentary majorities those mysterious undercurrents of opinion that threaten thrones. He was expansive and sometimes rash in his expansiveness, but remarkably adroit in his rashness; fertile in expedients, in postures and disguises, causing France to go in awe of Europe and Europe to go in awe of France. He undoubtedly loved his country but still preferred his family. He prized rulership more than authority, and authority more than dignity: an attitude having the serious drawback, being intent upon success, that it admits of deception and does not absolutely exclude baseness, but which has the advantage of preserving politics from violent reversals, the State from disruption and society from disaster. He was meticulous, correct, watchful, shrewd and indefatigable, sometimes contradicting and capable of repudiating himself. He dealt boldly with Austria at Ancona and stubbornly with England in Spain, bombarded Antwerp and compensated Pritchard. He sang the ‘Marseillaise’ with conviction. He was impervious to depression or lassitude, had no taste for beauty or idealism, no tendency to reckless generosity, utopianism, daydreaming, anger, personal vanity or fear. Indeed, he displayed every form of personal courage, as a general at Valmy and a common soldier at Jemmapes; he emerged smiling from eight attempts at regicide, had the fortitude of a grenadier and the moral courage of a philosopher. Nothing dismayed him except the possibility of a European collapse, and he had no fondness for major political adventures, being always ready to risk his life but never his work. He concealed his aims with the use of persuasion, seeking to be obeyed as a man of reason rather than as a king. He was observant but without intuition, little concerned with sensibilities but having a knowledge of men - that is to say, needing to see for himself in order to judge. He possessed a ready and penetrating good sense, practical wisdom, fluency of speech and a prodigious memory, upon which he constantly drew, in this respect resembling Caesar, Alexander, and Napoleon. He knew facts, details, dates and proper names, but ignored tendencies, passions, the diverse genius of the masses, the buried aspirations and hidden turbulence of souls – in a word, everything that may be termed the sub-conscious. He was accepted on the surface, but had little contact with the depths of France, maintaining his position by adroitness, governing too much and ruling too little, always his own prime-minister, excelling in the use of trivialities as an obstruction to the growth of great ideas. Mingled with his genuinely creative talent for civilization, order, and organization there was the spirit of pettifogging chicanery. The founder and advocate of a dynasty, he had in him something of a Charlemagne and something of an attorney. In short, as a lofty and original figure, a prince able to assert himself despite the misgivings of France, and to achieve power despite the jealousy of Europe, Louis-Philippe might be classed among the great men of his century and take his place among the great rulers of history if he had cared a little more for glory and had possessed as much feeling for grandeur as he had for expediency.

Louis-Philippe had been handsome as a young man and remained graceful in age. Although not always approved of by the nation as a whole, he was liked by the common people. He knew how to please, he had the gift of charm. Majesty was something that he lacked; the crown sat uneasily on him as king, and white hair did not suit him as an old man. His manners were those of the old regime, his behaviour that of the new, a blend of the aristocrat and the bourgeois that suited 1830. He was the embodiment of a period of transition, preserving the old forms of pronunciation and spelling in the service of new modes of thought. He wore the uniform of the Garde Nationale like Charles X and the sash of the Légion d’honneur like Napoleon.

He seldom went to chapel, and never hunted or went to the opera, being thus quite uninfluenced by clerics, masters-of-hounds and ballet-dancers, which had something to do with his bourgeois popularity. He kept no Court. He walked out with an umbrella under his arm, and this umbrella was for a long time a part of his image. He was interested in building, in gardening, and in medicine; he bled a postillion who had a fall from his horse, and would no more have been separated from his lancet than Henri III was from his dagger. The royalists laughed at this absurdity, saying that he was the first king who had ever shed blood in order to cure.

In the charges levelled by history against Louis-Philippe there is a distinction to be drawn. There were three types of charge, against royalty as such, against his reign, and against the king as an individual, and they belong in separate categories. The suppression of democratic rights, the sidetracking of progress, the violent repression of public demonstrations, the use of armed force to put down insurrection, the smothering of the real country by legal machinery and legality only half-enforced, with a privileged class of three hundred thousand – all these were the acts of royalty. The rejection of Belgium; the over-harsh conquest of Algeria, more barbarous than civilized, like the conquest of India by the English; the bad faith at Abd-el-Kadir and Blaye; the suborning of Deutz and compensation of Pritchard – these were acts of the reign. And family politics rather than a national policy were the acts of the king.

As we see, when the charges are thus classified, those against the king are diminished. His great fault was that he was over-modest in the name of France.

Why was this?

Louis-Philippe was too fatherly a king. His settled aim, with which nothing might be allowed to interfere, of nursing a family in order to hatch out a dynasty, made him wary of all else; it induced in him an excess of caution quite unsuited to a nation with 14 July in its civic tradition and Austerlitz in its military history.

Apart from this, and setting aside those public duties which must always take precedence, there was Louis-Philippe’s profound personal devotion to his family, which was entirely deserved. They were an admirable domestic group in which virtue went hand-in-hand with talent. One of his daughters, Marie d’Orléans, made a name for herself as an artist, as Charles d’Orléans did as a poet Her soul is manifest in the statue which she named Joan of Arc. Two others of his sons drew from Metternich the following rhetorical tribute: ‘They are young men such as one seldom sees and princes such as one never sees.’

Without distortion or exaggeration, that is the truth about Louis-Philippe.

To be by nature the ‘prince égalité’, embodying in himself the contradiction between the Restoration and the Revolution; to possess those disturbing qualities of the revolutionary which in a ruler become reassuring – this was his good fortune in 1830. Never was the man more wholly suited to the event; the one partook of the other. Louis-Philippe was the mood of 1830 embodied in a man. Moreover he had this especial recommendation for the throne, that he was an exile. He had been persecuted, a wanderer and poor. He had lived by working. In Switzerland, that heir by apanage to the richest princedoms of France had sold an old horse to buy food. At Reichenau he had given lessons in mathematics while his sister Adelaide did embroidery and needlework. These things, in association with royal blood, won the hearts of the bourgeoisie. He had with his own hands destroyed the last iron cage at Mont Saint-Michel, built to the order of Louis XI and used by Louis XV. He was the comrade of Dumouriez and the friend of Lafayette; he had been a member of the Jacobin Club; Mirabeau had clapped him on the shoulder and Danton had addressed him as ‘young man’. In 1793, when he was twenty-four, he had witnessed, from a back bench in the Convention, the trial of Louis XVI, so aptly named ‘that poor tyrant’. The blind clairvoyance of the Revolution, shattering monarchy in the person of the king and the king with the institution of monarchy, almost unconscious of the living man crushed beneath the weight of the idea; the huge clamour of the tribunal-assembly; the harsh, questioning voice of public fury to which Capet could find no answer; the stupefied wagging of the royal head under that terrifying blast; the relative innocence of everyone involved in the catastrophe, those condemning no less than those condemned – he had seen all these things, he had witnessed that delirium. He had seen the centuries arraigned at the bar of the Convention, and behind the unhappy figure of Louis XVI, the chance-comer made scapegoat, he had seen the formidable shadow of the real accused, which was monarchy; and there lingered in his heart an awed respect for the huge justice of the people, nearly as impersonal as the justice of God.

The impression made on him by the Revolution was enormous. His memory was a living picture of those tremendous years, lived minute by minute. Once, in the presence of a witness whose word we cannot doubt, he recited from memory the names of all the members of the Constituent Assembly beginning with the letter A.

He was a king who believed in openness. During his reign the press was free and the law-courts were free, and there was freedom of conscience and of speech. The September laws were unequivocal. Though well aware of the destructive power of light shed upon the privileged, he allowed his throne to be fully exposed to public scrutiny, and posterity will credit him with this good faith.

Like all historic personages who have left the stage, Louis-Philippe now stands arraigned at the bar of public opinion, but his trial is still only that of the first instance. The time has not yet come when history, speaking freely and with a mature voice, will pass final judgement upon him. Even the austere and illustrious historian, Louis Blanc, has recently modified his first verdict. Louis-Philippe was elected by the approximation known as ‘the 221’ and the impulse of the year 1830 – that is to say, by a demi-parliament and a demi-revolution; and in any event, viewing him with the detachment proper to an historian, we may not pass judgement on him here without, as we have already seen, making certain reservations in the name of the absolute principle of democracy. By that absolute standard, and outside the two essential rights, in the first place that of the individual and in the second that of the people as a whole, all is usurpation. But what we can already say, subject to these reservations, is that all in all, and however we may view him, Louis-Philippe, judged as himself and in terms of human goodness, will be known, to adopt the language of ancient history, as one of the best princes who ever acceded to a throne.

What can be held against him except the throne itself? Dismissing the monarch, we are left with the man. And the man is good – good sometimes to the point of being admirable. Often, amid the heaviest perplexities, and after spending the day in battle with the diplomacy of a whole continent, he would return exhausted to his private apartments, and there, despite his fatigue, would sit up all night immersed in the details of a criminal trial, believing that, important though it was to hold his own against all Europe, it was still more important to save a solitary man from the executioner. He obstinately opposed his Keeper of the Seal and disputed every inch of the way the claims of the guillotine with the public prosecutors, those ‘legal babblers’ as he called them. The dossiers were sometimes piled high on his desk and he studied them all, finding it intolerable that he should neglect the case of any poor wretch condemned to death. On one occasion he said to the person we have already mentioned, ‘I rescued seven last night.’ During the early years of his reign the death-penalty was virtually abolished; the erection of a public scaffold was an outrage to the king. But, the execution-place of La Grève having vanished with the senior branch of his family, a bourgeois Grève was instituted under the name of the Barrière Saint-Jacques. The ‘practical man’ felt the need of a more-or-less legitimate guillotine, and this was one of the triumphs of Casimir Perier, who stood for the bigoted side of the bourgeoisie, over Louis-Philippe, who stood for their liberalism. He annotated the case of Beccaria with his own hand, and after the Fieschi plot he exclaimed, ‘A pity I wasn’t wounded! I could have pardoned him.’ On another occasion, referring to the opposition of his ministers in the case of Barbès, one of the most noble figures of our time who was condemned to death in 1839 for his political activities, he wrote: ‘Sa grâce est accordée, il ne me reste plus qu’à l’obtenir.’*

For ourselves, in a tale wherein goodness is the pearl of rarest price, the man who was kind comes almost before the man who was great

Since Louis-Philippe has been severely judged by some, and perhaps over-harshly by others, it is only proper that a man who knew him, and today is himself a ghost, should bear witness on his behalf at the bar of History. His testimony, such as it is, is clearly and above all else disinterested. An epitaph written by the dead is sincere; a shade can console another shade, and living in the same shadows has the right to praise. There is little risk that anyone will say of those two exiles, ‘One flattered the other.’

IV

Flaws in the structure

At this moment, when our tale is about to plunge into the depths of one of those tragic clouds which obscure the beginning of Louis-Philippe’s reign, there can be no equivocation; it is essential that this book should state its position in respect of the king.

Louis-Philippe had assumed the royal authority without violence, without any positive act on his part, through a revolutionary chance which clearly had little to do with the real aims of the revolution, and in which, as Duke of Orléans, he had taken no personal initiative. He had been born a prince and believed that he was elected king. He had not conferred the mandate on himself or attempted to seize it. It had been offered him and he had accepted it in the conviction, certainly mistaken, that the offer was in accordance with the law and that to accept it was his duty. He held it in good faith. In all conscience we must declare that Louis-Philippe did occupy the throne in good faith, that democracy assailed him in good faith, and that neither side is to blame for the violence engendered by the struggle. A clash of principles is like a clash of elements, ocean fighting on the side of water, tempest on the side of air. The king defended monarchy and democracy defended the people; what was relative, which is monarchy, resisted what was absolute, which is democracy. Society shed blood in the conflict, but the present sufferings of society may later become its salvation. In any event, it is not for us to attribute blame to those who did the fighting. The right in the matter was not a Colossus of Rhodes with a foot on either side, monarchist and republican; it was indivisible and wholly on one side; but those who erred did so sincerely. The blind can no more be blamed than the partisans of La Vendée can be dismissed as brigands. Violent as the tempest was, human irresponsibility had a share in it.

Let me complete this account.

The government of 1830 was in trouble from the start, born on one day and obliged on the morrow to do battle. Scarcely was it installed than it began to feel the undertow of dissident movements directed against the newly erected and still insecure structure. Resistance was born the day after its installation, perhaps even the day before. Hostility increased month by month, and from being passive became active.

The July Revolution, little liked by the monarchs outside France, was in France subject to a variety of interpretations. God makes known His will to mankind through the event, an obscure text, written in cryptic language, which men instantly seek to decipher, producing hurried makeshift renderings filled with errors, gaps and contradictions. Very few minds are capable of reading the divine language. The wisest, calmest and most far-sighted go slowly to work, but by the time they produce their rendering the job has long been done and twenty different versions are on sale in the marketplace. Each interpretation gives birth to a political party, each contradiction to a political faction; and each party believes that it has the sole authentic gospel, each faction that it has its own light to shed.

Power itself is often no more than a faction. In all revolutions there are those who swim against the tide; they are the old political parties. To the old parties, wedded to the principle of heredity by Divine Right, it is legitimate to suppress revolution, since revolution is born of revolt. This is an error. The real party of revolt, in a democratic revolution, is not the people but the monarchy. Revolution is precisely the opposite of revolt. Every revolution, being a normal process, has its own legitimacy, sometimes dishonoured by false revolutionaries but which persists, even though sullied, and survives even though bloodstained. Revolutions are not born of chance but of necessity. A revolution is a return from the fictitious to the real. It happens because it had to happen.

Nevertheless the old legitimist parties assailed the 1830 revolution with all the venom engendered by false reasoning. Error provides excellent weapons. They attacked that revolution very shrewdly where it was most vulnerable, in the chink in its armour, its lack of logic; they attacked it for being monarchist. ‘Revolution,’ they cried to it, ‘why this king?’ Factions are blind men with a true aim.

The republicans uttered the same cry, but coming from them it was logical. What was blindness in the legitimists was clear-sightedness in the democrats. The 1830 revolution was bankrupt in the eyes of the people, and democracy bitterly reproached it with the fact. The July establishment was caught between two fires, that of the past and that of the future. It was the happening of a moment at grips with the centuries of monarchy on one side and enduring right on the other.

Moreover, in external affairs, being a revolution that had turned into a monarchy, the 1830 regime had to fall into line with the rest of Europe. Keeping the peace was an added complication. Harmony enforced for the wrong reasons may be more burdensome than war. Of this hidden conflict, always subdued but always stirring, was born a state of armed peace, that ruinous expedient of a civilization in itself suspect. The July Monarchy chafed, while accepting it, at the harness of a cabinet on European lines. Metternich would gladly have put it in leading-strings. Driven by the spirit of progress in France, it in its turn drove the reactionary monarchies of Europe. Being towed it was also a tower.

Meanwhile the internal problems piled up – pauperism, the proletariat, wages, education, the penal system, prostitution, the condition of women, riches, poverty, production, consumption, distribution, exchange, currency, credit, the rights of capital and labour – a fearsome burden.

Outside the political parties, as such, another stir became apparent. The democratic ferment found its echo in a philosophical ferment. The élite were as unsettled as the masses, differently but as greatly. While the theorists meditated, the ground beneath their feet – that is to say, the people – traversed by revolutionary currents, convulsively trembled as though with epilepsy. The thinkers, some isolated, some forming groups that were almost communities, pondered the questions of the hour, pacifically but deeply – dispassionate miners calmly driving their galleries in the depths of a volcano, scarcely disturbed by the deep rumblings or by glimpses of the furnace.

Their quietude was not the least noble aspect of that turbulent period. They left the question of rights to the politicians and concerned themselves with the question of happiness; what they looked for in society was the well-being of man. They endowed material problems, those of agriculture, industry, and commerce, with almost the dignity of a religion. In civilization as it comes to be shaped, a little by God and a great deal by man, interests coalesce, merge and amalgamate in such a fashion as to form a core of solid rock, following a law of dynamics patiently studied by the economists, those geologists of the body-politic. These men, grouped under a variety of labels, but who may be classified under the general heading of socialists, sought to pierce this rock and allow the living water of human felicity to gush forth from it.

This work extended to every field, from the question of capital punishment to the question of war, and to the Rights of Man proclaimed by the French Revolution they added the rights of women and children. It will not surprise the reader that, for a variety of reasons, we do not here proceed to a profound theoretical examination of the questions propounded by socialism. We will simply indicate what they were.

Problem One: the production of wealth.

Problem Two: its distribution.

Problem One embraces the question of labour and Problem Two that of wages, the first dealing with the use made of manpower and the second with the sharing of the amenities this manpower produces.

A proper use of manpower creates a strong economy, and a proper distribution of amenities leads to the happiness of the individual. Proper distribution does not imply an equal share but an equitable share. Equity is the essence of equality.

These two things combined – a strong economy and the happiness of the individual within it – lead to social prosperity, and social prosperity means a happy man, a free citizen, and a great nation.

England has solved the first of these problems. She is highly successful in creating wealth, but she distributes it badly. This half-solution brings her inevitably to the two extremes of monstrous wealth and monstrous poverty. All the amenities are enjoyed by the few and all the privations are suffered by the many, that is to say, the common people: privilege, favour, monopoly, feudalism, all these are produced by their labour. It is a false and dangerous state of affairs whereby the public wealth depends on private poverty and the greatness of the State is rooted in the sufferings of the individual: an ill-assorted greatness composed wholly of materialism, into which no moral element enters.

Communists and agrarian reformers believe they offer the solution to the second of these problems. They are mistaken. Their method of distribution kills production: equal sharing abolishes competition and, in consequence, labour. It is distribution carried out by a butcher, who kills what he distributes. It is impossible to accept these specious solutions. To destroy wealth is not to share it.

The two problems must be solved together if they are to be properly solved, and the two solutions must form part of a single whole.

To solve the first problem alone is to be either a Venice or an England. You will have artificial power like that of Venice or material power like that of England. You will be the bad rich man, and you will end in violence, as did Venice, or in bankruptcy, as England will do. And the world will leave you to the, because the world leaves everything to the that is based solely on egotism, everything that in the eyes of mankind does not represent a virtue or an idea.

It must be understood that in using the words Venice and England we are not talking about peoples but about social structures, oligarchies imposed upon nations, not the nations them-selves. For nations we have always respect and sympathy. Venice the people will revive. England the aristocracy will fall; but England the nation is immortal. Having said this we may proceed.

Solve these two problems – encourage the rich and protect the poor; abolish pauperdom; put an end to the unjust exploitation of the weak by the strong and a bridle on the innate jealousy of the man who is on his way for the man who has arrived; achieve a fair and brotherly relationship between work and wages; associate compulsory free education with the bringing-up of the young, and make knowledge the criterion of manhood; develop minds while finding work for hands; become both a powerful nation and a family of contented people; democratize private property not by abolishing it but by making it universal, so that every citizen without exception is an owner, which is easier than people think – in a word, learn how to produce wealth and how to divide it, and you will have accomplished the union of material and moral greatness; you will be worthy to call yourself France.

This, apart from the aberrations of a few particular sects, was the message of socialism; this was what it searched for amid the facts, the plan that it proposed to men’s minds. An admirable attempt, and one that we must revere.

It was problems such as this which so painfully afflicted Louis-Philippe: clashes of doctrine and the unforeseen necessity for statesmen to take account of the conflicting tendencies of all philosophies; the need to evolve a policy in tune with the old world and not too much in conflict with the revolutionary ideal; intimations of progress apparent beneath the turmoil; the parliamentary establishment and the man in the street; the need to compose the rivalries by which he was surrounded; his own faith in the revolution, and perhaps, finally, a sense of resignation born of the vague acceptance of an ultimate and higher right: his resolve to remain true to his own kin, his family feeling, a sincere respect for the people and his own honesty - these matters tormented Louis-Philippe and, steadfast and courageous though he was, at times overwhelmed him with the difficulty of being king.

He had a strong sense of the structure crumbling beneath him, but it was not a crumbling into dust, since France was more than ever France.

There were ominous threats on the horizon. A strange creeping shadow was gradually enveloping men, affairs and ideas, a shadow born of anger and renewed convictions. Things that had been hurriedly suppressed were again astir and in ferment. There was unrest in the air, a mingling of truths and sophistries which caused honest men at times to catch their breath and spirits to tremble in the general unease like leaves fluttering at the approach of a storm. Such was the tension that any chance-comer, even an unknown, might at moments strike a spark; but then the dusky obscurity closed in again. At intervals deep, sullen rumblings testified to the charge of thunder in the gathering clouds.

Scarcely twenty months after the July Revolution, the year 1832 opened with portents of imminent disaster. A distressed populace and underfed workers; the last Prince de Condé vanished into limbo; Brussels driving out the House of Nassau as Paris had driven out the Bourbons; Belgium offering herself to a French prince and handed over to an English prince; the Russian hatred of Tsar Nicholas; at our backs two southern demons, Ferdinand in Spain and Miguel in Portugal; the earth shaking in Italy; Metternich reaching out for Bologna and France dealing roughly with the Austrians at Ancona; the sinister sound in the north of a hammer renailing Poland in her coffin; angry eyes watching France from every corner of Europe; England, that suspect ally, ready to give a push to whatever was tottering and to fling herself upon anything ready to fall; the peerage sheltering behind Beccaria to protect four heads from the law; the fleur-de-lis scratched off the royal coach, and the cross wrenched off Notre-Dame; Lafayette diminished, Laffitte ruined; Benjamin Constant dead in poverty, Casimir Perier dead of the exhaustion of power; political sickness and social sickness declaring themselves simultaneously in the two capitals of the kingdom, the capital of intellect and the capital of labour – civil war in Paris and servile war in Lyons, and in both cities the same furnace-glow; the red glare of the crater reflected in the scowls of the people; the south fanatical, the west in turmoil; the Duchesse de Berry in La Vendée; plots, conspiracies, upheavals and finally cholera, adding to the growling mutter of ideas the dark tumult of events.

V

Facts making History which History ignores

By the end of April the whole situation had worsened. The ferment was coming to the boil. Since 1830 there had been small, sporadic uprisings, rapidly suppressed, but which broke out again: symptoms of the huge underlying unrest. Something terrible was brewing, and there were portents, still unclear but vaguely to be discerned, of possible revolution. France was watching Paris and Paris was watching the Faubourg Saint-Antoine.

The Faubourg Saint-Antoine, surreptitiously heated, was beginning to boil over. The taverns in the Rue de Charonne, odd though the adjectives may sound when applied to such places, were at once sober and tempestuous.

In these places the government was openly under attack, and the question of ‘to fight or do nothing’ was publicly debated. There were back-rooms where workers were made to swear ‘that they would come out on to the streets at the first sound of the alarm and would fight, no matter how numerous their enemies’. When they had pledged themselves a man seated in a corner of the room would proclaim in a ringing voice, ‘You have taken the oath! You have sworn!’ Sometimes the proceedings took place in an upstairs room behind closed doors, and here the ceremony was almost masonic. The initiate was required to swear ‘that he would serve the cause as he would serve his own father’. This was the formula.

In the downstairs rooms ‘subversive’ pamphlets were read –‘blackguarding the government’, according to a secret report. Remarks such as the following were heard: ‘I don’t know the names of the leaders. We shall only be given two hours’ notice on the day.’ A workman said: ‘There are three hundred of us. If we put in ten sous each that will be 150 francs for ball and powder.’ Another said: ‘I don’t ask for six months or even two. We can be on level terms with the government in a fortnight. With 25,000 men we can stand up to them.’ Another: ‘ I never get any sleep because I’m up all night making cartridges.’ Now and then, ‘well-dressed men, looking like bourgeois’ appeared, causing ‘some embarrassment’ and ‘seeming to be in positions of command’. They shook hands with ‘the more important’ and quickly departed, never staying longer than ten minutes. Significant remarks were exchanged in undertones. ‘The plot is ripe, it’s all prepared’ … ‘Everybody was muttering things like this,’ in the words of a man who was present. Such was the state of excitement that one day a workman cried aloud in a café, ‘We haven’t the weapons!’, to which one of his comrades replied, ‘But the military have!’ – unconsciously parodying Bonaparte’s proclamation to the army in Italy. ‘When it came to something very secret,’ another agent’s report said, ‘they did not divulge it in those places.’ It is hard to imagine what more they had to conceal, when so much was said.

Some meetings were held at regular intervals, and certain of these were confined to eight or ten men, always the same. Other meetings were open to all comers, and the rooms were so crowded that many had to stand. There were men who came from enthusiasm for the cause, and others ‘because it was on their way to work’. As in the Revolution, there were ardent women who embraced all newcomers.

Other revealing facts came to light. A man walked into a café, had a drink and walked out again, saying to the proprietor: ‘The revolution will pay.’ Revolutionary agents were elected by vote in a café off the Rue de Charonne, the votes being collected in caps. One group of workers met on the premises of a fencing-master in the Rue de Cotte. There was a trophy on the wall consisting of wooden two-handed swords (espadons), singlesticks, bludgeons, and foils. One day the buttons were taken off the foils. One of the men said, ‘There are twenty-five of us, but they don’t reckon I’m worth anything. I’m just a cog in the machine.’ He was Quénisset, later to become famous.

Small, significant trifles acquired a strange notoriety. A woman sweeping her doorstep said to another woman, ‘We’ve been doing hard labour for a long time, making cartridges.’ Posters appeared in the open street, appeals addressed to the Garde Nationale in the départements. One of these was signed, ‘Burtot, wine-merchant’.

One day a man with a black beard and an Italian accent stood on a boundary-stone outside the door of a wine-shop in the Marché Lenoir and read out a striking document that seemed to have emanated from a secret source. Groups of people gathered and applauded. The passages which most stirred them have been recorded. ‘Our doctrines are suppressed, our proclamations torn up, our billposters hounded and imprisoned … The recent collapse of the textile industry has converted many moderates … The future of the people is taking shape in our secret ranks … This is the choice that confronts us: action or reaction, revolution or counterrevolution. For no one in these days believes any longer in neutralism or inertia. For the people or against the people, that is the question, and there is no other… On the day we no longer suit you, destroy us; but until then, help us in what we are doing.’ This was read out in broad daylight.

Other still more startling occurrences were, because of their very audacity, viewed with suspicion by the people. On 4 April 1832 a man climbed on to the boundary-stone at the corner of the Rue Sainte-Marguerite and proclaimed, ‘I am a Babouviste!’; but they fancied that behind Babeuf lurked Gisquet, the Prefect of Police.

This particular speaker said, among other things:

‘Down with property! The left-wing opposition is cowardly and treacherous. They preach revolution for effect. They call them-selves democrats so as not to be beaten and royalists so as not to have to fight. The republicans are wolves in sheeps’ clothing. Citizen workers, beware of the republicans!’

‘Silence, citizen spy!’ shouted a workman, and this brought the speech to an end.

There were strange episodes. One evening a workman near the canal met a ‘well-dressed man’ who said to him: ‘Where are you going, citizen?’ … ‘Monsieur,’ the workman replied, ‘I have not the pleasure of your acquaintance’ … ‘But I know you well,’ the man said. And he went on: ‘Don’t be afraid. I’m an agent of the committee. You’re suspected of not being reliable. Let me warn you, if you give anything away, that you’re being watched.’ He then shook the workman by the hand and left him, saying: ‘We shall meet again.’

Police agents reported scraps of conversation overheard not only in the cafés but in the street.

‘Get yourself signed on quickly,’ a weaver said to a cabinetmaker.

‘Why?’

‘There’s going to be shooting.’

Two ragged pedestrians exchanged remarks reminiscent of the jacquerie:

‘Who governs us?’

‘Why, Monsieur Philippe.’

‘No, it’s the bourgeoisie.’

It would be wrong to suppose that we use that word jacquerie in any pejorative sense. The ‘Jacques’ were the poor, and right is on the side of the hungry.

A man was heard to say to another: ‘We have a fine plan of campaign.’

Four men seated in a ditch at the Barrière-du-Trône crossroads were holding a muttered conversation of which the following sentence was overheard:

‘They’ll do their best not to let him go for any more walks in Paris.’

Who was the ‘he’? An ominous riddle.

‘The principal leaders’, as they were called in the Faubourg, kept aloof. They were believed to meet in a café near the Pointe Sainte-Eustache, and a certain Auguste, president of the Tailors’ Benefit Society in the Rue Mondétour, was said to be the link between them and the workers of the Faubourg Saint-Antoine. However, the identity of these leaders was never finally established, and no positive fact emerged to invalidate the lofty reply made later by one of the accused on trial by the Court of Peers in answer to the question:

‘Who was your chief?’

‘I knew of no chief, and recognized none.’

But all these were no more than words, suggestive but inconclusive, fragments of hearsay, remarks often without context. There were other portents.

A carpenter engaged in the erection of a wooden fence round the site of a house under construction picked up on the site a fragment of a torn letter on which he read the following: ‘The committee must take steps to prevent the enlistment in its sections of recruits for other associations …’ And further: ‘We have learned that there are rifles, to the number of five or six thousand, at an armourer’s shop in the Rue du Faubourg-Poissonnière (No. 5 bis). That section has no arms.’

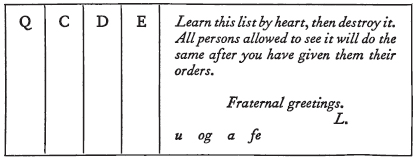

This so startled the carpenter that he showed it to his comrades, and they found near to it another torn sheet of paper which was even more revealing. We reproduce the exact format for the sake of the document’s historic interest.

The persons in the secret learned only later what the four capital letters stood for – Quinturians, Centurians, Decurians, Éclaireurs (scouts). The letters u og a fe were a coded date – 15 April 1832. Under each of the capital letters were names with brief remarks appended. Thus: Q. Bannerel. 8 muskets. 83 cartridges. A safe man. – C. Boubière. I pistol. A pound of powder. – E. Teissier. I sabre. I ammunition pouch. Reliable. – Terreur. 8 muskets. Sturdy … And so on.

Finally a third sheet was found bearing, pencilled but still legible, a further and cryptic list of names. The loyal citizen into whose possession these documents came was familiar with their meaning. It seems that the names on the third list were the code-names (such as Kosciusko and Caius Gracchus) of all the sections of the Société des Droits de l’Homme in the fourth Paris arrondissement, with, in some cases, the name of the section-chief and an indication of his address. Today these hitherto unknown facts, which now are only a part of history, may be published. It may be added that this League of the Rights of Man appears to have been founded at a later date than that on which the pencilled list was found. At that stage, presumably, it was still in process of formation.

But on top of the spoken and written clues, concrete evidence was coming to light.

A raid on a second-hand dealer’s shop in the Rue Popincourt unearthed, in the drawer of a commode, seven large sheets of grey paper, folded in four, containing twenty-six squares of similar paper folded in the form of cartridges, together with a card on which was written:

Saltpetre

12 ounces.

Sulphur

2 ounces.

Charcoal

2 ½ ounces.

Water

2 ounces.

The official report of the raid stated that the drawer had a strong smell of gunpowder.

A builder’s labourer on his way home from work left, on a bench near the Pont d’Austerlitz, a small package which was handed in to the watch. It was found to contain two pamphlets signed Lahautière, a song entitled, ‘Workers Unite’ and a tin box filled with cartridges.

Children playing in the least frequented part of the boulevard between Père-Lachaise and the Barrière-du-Trône found in a ditch, under a pile of road-chippings and rubble, a bag containing a bullet-mould, a wooden form for making cartridges, a bowl in which there were grains of hunting-powder and a small metal cook-pot containing remnants of molten lead.

Police officers carrying out a surprise raid at five in the morning on the house of a man named Pardon (he later became head of the Barricade-Merry section, and was killed in the uprising of April 1834) found him standing by his bed making cartridges, one of which he had in his hand.

Two labourers were seen to meet after working hours outside a café in an alleyway near the Barrière Charenton. One passed the other a pistol, taking it from under his smock; but then, seeing that it was damp with sweat, he took it back and re-primed it. The men then separated.

A man named Gallais boasted of having a stock of 700 cartridges and 24 musket-flints.

The Government had word one day that firearms and 200,000 cartridges had been distributed in the faubourgs, and, a week later, a further 30,000 cartridges. The police, remarkably enough, were able to lay hands on none of this store. An intercepted letter contained the following passage: ‘The day is not far distant when within four hours by the clock 80,000 citizens will be under arms.’

It was a state of open, one can almost say tranquil, ferment. The coming insurrection made its preparations calmly under the nose of the authorities. No singularity was lacking in this crisis that was still subterranean but already plainly manifest. Middle-class gentlemen discussed it amiably with work-people, inquiring after the progress of the uprising, much as they might have asked after the health of their wives.

A furniture-dealer in the Rue Moreau asked, ‘Well, and when are you going to attack?’, and another shopkeeper said, ‘You’ll be attacking soon. I know it. A month ago there were only 15,000 of you; today there are 25,000.’ He offered his shotgun for sale, and his neighbour offered a small pistol at a price of seven francs.

The revolutionary fever was steadily rising, and no part of Paris, or of all France, was exempt. The tide was flowing everywhere. Secret societies, like a cancer in the human body, were spreading throughout the country. Out of the Society of Friends of the People, which was both open and secret, sprang the League of the Rights of Man, which, dating one of its Orders of the day ‘Pluviôse, in the Fortieth Year of the Republic’, was destined to survive court orders decreeing its dissolution, and which made no bones about calling its sections by such suggestive names as ‘The Pikes’, ‘The Alarm Gun’ and ‘The Phrygian Bonnet’.

The League of the Rights of Man in its turn gave birth to the League of Action, composed of eager spirits who broke away in order to progress faster. Other new associations sought to lure members from the parent bodies, and section-leaders complained of this. There were the Société Gauloise and the Committee for the Organization of the Municipalities, also societies advocating the Liberty of the Press, the Liberty of the Individual, Popular Education, and one which opposed indirect taxation. There was the Society of Egalitarian Workers, which divided into three branches, Egalitarians, Communists, and Reformists. There was the Armée des Bastilles, a fighting force organized on military lines – units of four men under a corporal, ten under a sergeant, twenty under a second-lieutenant, and forty under a lieutenant – in which never more than five men knew one another, a system combining caution with audacity which seems to have owed something to Venetian models: its Central Committee controlled two branches, the Action branch and the main body of the Armée. A legitimist society, the Chevaliers de la Fidélité, tried to establish itself among these republican bodies, but it was denounced and repudiated.

The Paris societies overflowed into the larger provincial cities. Lyons, Nantes, Lille, and Marseilles had their League of the Rights of Man, among others. Aix had a revolutionary society known as the Cougourde. We have already used that word.

In Paris there was scarcely less uproar in the Faubourg Saint-Marceau than in the Faubourg Saint-Antoine, and the university schools were as agitated as the workers’ quarters. A café in the Rue Saint-Hyacinthe, and the Estaminet des Sept-Billards, in the Rue des Mathurins-Saint-Jacques, were the students’ headquarters. The Society of the Friends of ABC, which was affiliated with the ‘Mutualists’ in Angers and the Cougourde in Aix, met, as we have seen, at the Café Musain, but the same group also gathered at the cabaret-restaurant near the Rue Mondétour called Corinth. These meetings were secret, but others were entirely public, as may be gathered from the following extract from the cross-examination of a witness in one of the subsequent trials: ‘Where was this meeting held?’ … ‘In the Rue de la Paix’ … ‘In whose house?’ … ‘In the street’ … ‘How many sections attended?’ … ‘Only one’ … ‘Which one?’ … ‘The Manuel Section’ … ‘Who was its leader?’ … ‘I was’ … ‘You are too young to have taken the grave decision to attack the Government. Where did your orders come from?’… ‘From the Central Committee.’

The army was being subverted at the same time as the civil population, as was later proved by the mutinies in Belfort, Lunéville, and Épinal. The insurrectionists counted on the support of several regiments of the line and on the Twentieth Light Infantry.

‘Trees of liberty’ – tall poles surmounted by a red bonnet – were erected in Burgundy and in a number of towns in the south.

This, broadly, was the situation, and nowhere was it more acute, or more openly manifest, than in the Faubourg Saint-Antoine, which was, so to say, its nerve centre. The ancient working-class quarter, crowded as an ant-heap and laborious, courageous and touchy as a hive of bees, simmered in the anticipation of a hoped-for upheaval, although its state of commotion in no way affected its daily work. It is hard to convey an impression of that lively and lowering countenance. Desperate hardship is concealed beneath the attic roofs of that quarter, and so are rare and ardent minds; and the moment of danger occurs when these two extremes, of poverty and intelligence, come together.

The Faubourg Saint-Antoine had other reasons for its feverish state. It was particularly affected by the economic crises, bankruptcies, strikes, unemployment, that are inseparable from any time of major political unrest. In a revolutionary period poverty is both a cause and an effect, aggravated by the very blows it strikes. Those proud, hard-working people, charged to the utmost with latent energies and always prompt to explode, exasperated, deep-rooted, undermined, seemed to be only awaiting the striking of a spark. Whenever there is thunder in the air, borne on the wind of events, we are bound to think of the Faubourg Saint-Antoine and the fateful chance which has set this powder-mill of suffering and political thought on the threshold of Paris.

The drinking-places of the quarter, so constantly referred to in this brief account, have acquired an historic notoriety. In troubled times their customers grow more drunk on words than on wine. A prophetic sense pervades them, an intimation of the future, exalting hearts and minds. They resemble those taverns on Mount Aventine built round the Sybil’s cave and stirred by the sacred breath, where the tables were virtually tripods and one drank what Annius calls ‘the Sybilline wine’.

The Faubourg Saint-Antoine is a people’s stronghold. Times of revolutionary upheaval cause breaches in its walls through which the popular will, the sovereignty of the people, bursts out. That sovereignty may behave badly; it blunders, like all human action, but even in its blunderings, like the blind Cyclops, it remains great.

In 1793, according to whether the prevailing mood was good or evil, idealistic or fanatical, masses poured out of it which were heroic or simply barbarous. We must account for the latter word. What did they want, those violent men, ragged, bellowing and wild-eyed, who with clubs and pikes poured through the ancient streets of distracted Paris? They wanted to put an end to oppression, tyranny, and the sword; they wanted work for all men, education for their children, security for their wives, liberty, equality, fraternity, food enough to go round, freedom of thought, the Edenization of the world. In a word, they wanted Progress, that hallowed, good, and gentle thing, and they demanded it in a terrible fashion, with oaths on their lips and weapons in their hands. They were barbarous, yes; but barbarians in the cause of civilization.

They furiously proclaimed the right; they wanted to drive mankind into Paradise, even if it could only be done by terror. They looked like barbarians and were saviours. Wearing a mask of darkness, they clamoured for light.

And confronting these men, wild and terrible as we agree they were, but wild and terrible for good, there were men of quite another kind, smiling and adorned with ribbons and stars, silk-stockinged, yellow-gloved and with polished boots; men who, seated round a velvet table-cloth by a marble fireplace, gently insisted on the preservation of the past, of the Middle Ages, of divine right, of bigotry, ignorance, enslavement, the death-penalty and war, and who, talking in polished undertones, glorified the sword and the executioner’s block. For our part, if we had to choose between the barbarians of civilization and those civilized upholders of barbarism we would choose the former.

But there is mercifully, another way. No desperate step is needed, whether forward or backward, neither despotism nor terrorism. What we seek is progress by gradual degrees.

God is looking to it. Gradualness is the whole policy of God.

VI

Enjolras and his lieutenants

At about this time, Enjolras, with an eye to possible contingencies, made a tactful survey of policy among his followers. While they were holding counsel in the Café Musain, he said, interlarding his words with a few cryptic but meaningful metaphors:

‘It’s just as well to know where one stands and whom one can count on. If one wants active fighters one has to create them; no harm in possessing weapons. People trying to pass are always more likely to be gored if there are oxen in the street. So let’s take stock of our manpower. How many of us are there? No point in putting it off. Revolutionaries should always be in a hurry; progress has no time to waste. We must be ready for the unexpected and not let ourselves be caught out. It’s a matter of reviewing all the stitches we’ve sewn and seeing if they’ll hold, and it needs to be done at once. Courfeyrac, you can call on the polytechnic students, it’s their free day. Today’s Wednesday, isn’t it? Feuilly, you can call on the workers at the Glacière. Combeferre has said he’ll go to Picpus, there are a lot of good men there. Prouvaire, the stone-masons show signs of cooling off, you’d better find out how things are at the lodge in the Rue de Grenelle-Saint-Honoré. Joly can look in at the Dupuytren hospital and take the pulse of the medical students, and Bossuet can do the same with the law students at the Palais de Justice. I’ll do the Cougourde.’

‘And that’s the lot,’ said Courfeyrac.

‘No.’

‘What else is there?’

‘Something very important.’

‘What’s that?’ asked Combeferre.

‘The Barrière du Maine,’ said Enjolras.

He was silent for a moment, seeming plunged in thought, and then said:

‘There are marble-workers at the Barrière du Maine, and painters and workers in the sculptors’ studios. They’re keen, on the whole, but inclined to blow hot and cold. I don’t know what’s got into them recently. They seem to have lost interest, they spend their whole time playing dominoes. It’s important for someone to go and talk to them, and talk bluntly. Their place is the Café Richefeu and they’re always there between twelve and one. It needs a puff of air to brighten up those embers. I was going to ask that dreamy character, Marius, but he doesn’t come here any more. So I need someone for the Barrière du Maine, and I’ve no one to send.’

‘There’s me,’ said Grantaire. ‘I’m here.’

‘You?’

‘Why not?’

‘You’ll go out and preach republicanism, rouse up the halfhearted in the name of principle?’

‘Why shouldn’t I?’

‘Would you be any good at it?’

‘I’d quite like to try,’ said Grantaire.

‘But you don’t believe in anything?’

‘I believe in you.’

‘Grantaire, do you really want to do me a service?’

‘Anything you like – I’d black your boots.’

‘Then keep out of our affairs. Stick to your absinthe.’

‘That’s ungrateful of you, Enjolras.’

‘You really think you’re man enough to go to the Barrière du Maine? You’d be capable of it?’

‘I’m quite capable of walking along the Rue des Grès, up the Rue Monsieur-le-Prince to the Rue de Vaugirard, along the Rue d’Assas, across the Boulevard du Montparnasse and through the Barrière to the Café Richefeu. My boots are good enough.’

‘How well do you know that lot at the Richefeu?’

‘Not very well, but we’re quite friendly.’

‘What would you say to them?’

‘Well, I’d talk to them about Robespierre and Danton and the principles of the Revolution.’

‘You would?’

‘Yes, me. Nobody does me justice. When I really go for something I’m tremendous. I’ve read Prudhomme and the Contrat Social and I know the Constitution of the Year Two by heart. “The liberty of the citizen ends where that of another citizen begins.” Do you think I’m an ignoramus? I have an old assignat in my drawer. The Rights of Man, the Sovereignty of the people, I know the lot. I’m even a bit of an Hébertist. I can hold forth sublimely –for six hours on end, if need be, by the clock.’

‘Be serious,’ said Enjolras.

‘I’m madly serious.’

Enjolras considered for a few moments, then made a gesture of decision.

‘Very well, Grantaire,’ he said soberly. ‘I’ll give you a trial. You shall go to the Barrière du Maine.’

Grantaire was living in a furnished room very near the café. He went out and was back in five minutes wearing a Robespierre waistcoat.

‘Red,’ he said, looking meaningfully at Enjolras. Smoothing the red points of the waistcoat with a firm hand, he bent towards him. ‘Don’t worry,’ he said, and putting on his hat marched resolutely to the door.

A quarter of an hour later the back-room at the Café Musain was empty. All the ‘Friends of ABC’ had departed on their respective tasks. Enjolras, who had reserved the Cougourde d’Aix for himself, was the last to leave.

Those members of the Cougourde d’Aix who were in Paris were accustomed to meet in the Plaine d’Issy, in one of the abandoned quarries which are so numerous on that side of the city. While he was on his way there Enjolras reviewed the situation. The gravity of the times was apparent. When events which are the premonitory symptoms of social sickness stir ponderously into motion the least complication may impede them. It is a time of false starts and fresh beginnings. Enjolras had a sense of a splendid new dawn breaking through the clouds on the horizon. Who could tell? Perhaps the moment was very near when, inspiring thought, the people would assert their rights, and the Revolution, majestically regaining possession of France, would say to the world: ‘More is to follow!’ Enjolras was happy. The temperature was rising. He had, at that moment, a powder-train of friends scattered through Paris, and he was rehearsing in his mind an electrifying speech that would spark off the general explosion – a speech combining the depth and philosophic eloquence of Combeferre, the cosmopolitan ardours of Feuilly, the verve of Courfeyrac, the laughter of Bahorel, the melancholy of Jean Prouvaire, the knowledge of Joly, and the sarcasm of Bossuet. All of them working together. Surely the result must justify their labours. All was well. And this brought him to the thought of Grantaire. The Barrière du Maine was only a little off his way. Why should he not make a slight detour to look in at the Café Richefeu and see how he was getting on?

The clock-tower in the Rue de Vaugirard was striking when he thrust open the door of the café and, letting it swing to behind him, stood with folded arms in the doorway contemplating the crowded room filled with tables, men and tobacco-smoke.

Grantaire was seated opposite another man at a marble-topped table scattered with dominoes. He was banging on the marble with his fist, and this was what Enjolras overheard:

‘Double six.’

‘Blast! I can’t go.’

‘You’ll have to pass. A two.’

‘A six.’

And so on. Grantaire was wholly absorbed in the game.