At dawn one day, when early morning mist was drifting sluggishly across the clearing, I stole out of the forest. The Hobgoblins were still fast asleep in their hollow tree trunks. They had returned from a successful raid during the night, bloated and humming with contentment. Now, snoring and squeaking in their sleep like gorged opossums, they were digesting the fear they had absorbed. I gave them a last, distasteful glance, then set off for the beach.

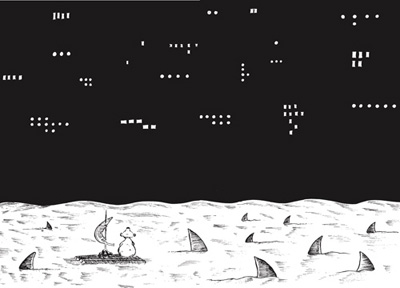

I escape by sea

In the days beforehand I had dragged some small fallen trees from the edge of the forest to the shore and lashed them together with creeper. As the sail of my raft I used a big, fat palm leaf. I had scooped out a few coconuts, filled them with water, sealed them up again, and tied them to the mast with thin lianas, together with the unopened coconuts that were to serve as food. That was the sum total of my supplies.

I pushed my raft out into the breakers. The tide was just turning, so I was quickly carried out to sea. Where would the wind and waves take me? I had dispensed with a rudder on the principle that fate must be given a chance.

I was feeling wonderful. It seemed that the wind in my fur and the wild sea beneath me existed solely to transport me into a world of adventure. Could anything be more exciting than a journey into the unknown, a voyage of discovery across the great, wide ocean?

Becalmed

Three hours later my raft lay becalmed, bobbing in the midst of a vast expanse of motionless water. Could anything be more tedious than a sea voyage? The sea? Pooh! Just a salt-water desert, smooth and featureless as an enormous mirror. Any pool in the Hobgoblins’ forest had more to offer. Nothing happened, not even a seagull flew past.

I had been hoping for unknown continents and mysterious islands, or at least for a Minipirates’ ship, but not even a message-in-a-bottle floated by. After a considerable time, a rotten plank came my way. It took hours to drift past. That was the most interesting sight I’d encountered on my voyage to date. I cracked open a coconut and began to feel bored.

The younger you are, the more excruciating boredom becomes. Seconds crawl by like minutes, minutes like hours. You feel you’re being stretched on the rack – a time-rack, as it were – and very slowly torn apart. An infinite succession of wavelets splashes past, the sky is a bright blue vault of infinite extent. If you’re a relatively inexperienced seafarer and watch the horizon, you feel it must disclose something breathtaking at any moment. But all that awaits you beyond it is another horizon. I would have welcomed any diversion – a storm, a seaquake, a terrible sea monster – but all I saw for weeks on end were waves, sky, and horizons.

I was beginning to yearn for the Hobgoblins’ nauseating company when the situation changed dramatically. Although there was little wind, the sea had been unusually agitated for some days. The calm green water had transformed itself into a turmoil of grey foam, the air was filled with soot and the smell of rusty metal. Hopping excitedly to and fro on my raft, I vainly strove to discover the cause of it all. Then came a sound like never-ending thunder. It drew nearer and nearer, and the sky grew darker by the minute. I had my longed-for storm at last.

The SS Moloch

Or so I thought until a huge, black, iron ship appeared in the distance.

She had at least a thousand funnels, so tall that their tops were hidden by the smoke that rose from them. Soot entirely obscured the sky and turned the sea the colour of Indian ink, thanks to the smuts that kept raining down on it like black snow.

At first I thought the ship had come straight from hell to crush me, she seemed to be bearing down on me so purposefully. Then I was lifted by the bow wave and swept aside like a cork. I could now observe the iron colossus from a safe distance as it glided by like a dark mountain of metal. The screws that propelled it must have been bigger than windmills.

I don’t know how long the ship took to sail right past and disappear from view, but it must have been about a day and a night. Not that I knew it at the time, she was the SS Moloch, the largest ship that ever sailed the seas.

From the

‘Encyclopedia of Marvels, Life Forms

and Other Phenomena of Zamonia and its Environs’

by Professor Abdullah Nightingale

SS Moloch, The. With 1214 funnels and a gross registered tonnage of 936,589 tons, the Moloch is held to be the biggest ship in the world. No precise specifications are available, or none that can be scientifically validated, because no one who has set foot in the Moloch has ever returned. Thousands of tales are told about this vessel, needless to say, but none that has any recognizable claim to credibility.

At night, thousands of portholes – the windows of that floating metropolis – shone brighter than the stars. The pounding of the engines was deafening. They sounded like an ironclad army tramping across the ocean.

During the daytime I tried to spot some of the crew, but the deck was so far above me I could scarcely make out a thing. Whenever distant figures came to the rail and threw garbage over the side, as they did from time to time, I set up a tremendous hullabaloo. I yelled and gesticulated, jumped up and down on the raft and waved my palm-leaf sail, but my efforts were as futile as the Minipirates’ attempts to board a merchantman.

They weren’t without their dangers, too. On more than one occasion I was almost sucked into the wash of the gigantic propellers, and swarms of sharks crowded around the hull to fight for the scraps of food that were forever being thrown overboard. At times the creatures were so numerous that I could have walked to the ship’s side across their backs.

A voice in my head

But the most astonishing feature was something else. In spite of the huge vessel’s monstrous ugliness, it held a mysterious fascination for me. There was no discernible reason for this. Although the ship was repulsive in every way, my dearest wish was to sail the seas in her. This desire had taken root in me when the Moloch first appeared on the horizon, a tiny speck growing bigger the nearer she came. While she was passing my raft it became positively overpowering.

‘Come!’ said a voice in my head.

‘Come aboard the Moloch!’

The words had an unearthly ring, as if uttered by some disembodied being in the world hereafter.

‘Come!’ it said. ‘Come aboard the Moloch!’

I should have liked nothing better than to obey its summons. I now know it was my good fortune that the sharks formed an insurmountable barrier between me and the ship, but at the time it nearly broke my little heart to watch the Moloch sail away.

‘Come! Come aboard the Moloch!’

The gigantic ship eventually disappeared from view, but the sky remained dark for a long time to come, like the aftermath of a receding storm.

The voice in my head grew ever fainter.

‘Come!’ it said, very softly. ‘Come aboard the Moloch!’

Then they were gone, both the ship and the voice. It saddened me somehow to think I would never see the Moloch again. I wasn’t to know what an important part she would play in one of my lives.

The sea had been calm and silvery again for days, the sky clear except when an occasional little fair-weather cloud came drifting over the horizon. Having seen the Moloch, I had lost all respect for my own craft. There couldn’t have been a more cogent demonstration of the difference between a ship and a raft.

I was just debating whether to jump overboard and strike out for land when I heard two voices, loud and clear.

‘I did, take it from me!’ said one.

‘No, you didn’t!’ snapped the other.

I peered in all directions. There was nothing to be seen.

‘I did, so!’ the first voice insisted.

‘Pull the other one!’ said the second.

I stood on tiptoe. Still nothing in sight far and wide.

Nothing but waves.

‘But I told you only the other day, don’t pretend I didn’t!’

Was madness knocking at my door? Many a doughty mariner had been driven insane by the monotony of life at sea. All I could see were waves: little ones, middling ones, and two quite sizeable specimens heading straight for me. The nearer they got, the more audible the voices became.

‘Who do you think you are, giving me orders? If anyone gives the orders around here, it’s me!’

The two waves were having an argument.

From the

‘Encyclopedia of Marvels, Life Forms

and Other Phenomena of Zamonia and its Environs’

by Professor Abdullah Nightingale

Babbling Billows, The. Such waves almost always come into being in very remote and uneventful sea areas seldom frequented by ships, usually during prolonged spells of calm weather. No detailed scientific study or analysis of their origins has yet been undertaken because Babbling Billows have a tendency to drive their victims insane. The few scientists who have ventured to study them are now confined under guard in padded cells or lying on the ocean floor in the form of skeletons with tropical fish swimming in and out of them.

Babbling Billows normally appear only to shipwrecked sailors. They circle their helpless victims for days or weeks on end, bombarding them with tasteless jokes and cynical comments on the hopelessness of their predicament until the unfortunate seafarers, already weakened by thirst and exposure to the sun, completely lose their reason. An ancient Zamonian myth constitutes the basis of the popular fallacy that Babbling Billows are the material manifestations of oceanic boredom.

More shipwrecked sailors have, in fact, been killed by Babbling Billows than by thirst, but that I didn’t know at the time. To me they seemed no more than a welcome distraction from the tedium of the doldrums.

The two waves were quite close by now. When they saw me on my ramshackle raft, naked and bleached by the scorching sun, they had a fit of the giggles.

‘Good heavens!’ cried one. ‘What have we here?’

‘A luxury liner,’ cackled the other. ‘Complete with sun deck!’

They sloshed to and fro with laughter. Although I wasn’t sure what they meant, I thought it wise to establish contact with them by laughing too.

They circled the raft like a brace of sharks.

‘I expect you think you’ve gone mad, don’t you?’ asked one.

‘Babbling Billows are the first symptom of sunstroke, did you know that?’ asked the other.

‘Yes, and after that come singing fish. Why not make it easier on yourself? Just jump in!’

They sloshed to and fro, pulling frightful faces.

‘Hoo-oo-oo!’ cried one wave.

‘Woo-oo-oo!’ cried the other.

‘We are the Waves of Terror!’

‘Go on, jump! Put yourself out of your misery!’

I had no intention of jumping. On the contrary, I was delighted that someone was making an effort to entertain me at last. I sat on the edge of the raft and watched the waves’ performance with amusement.

‘But seriously, youngster,’ said one of them, aware that they were getting nowhere, ‘who are you? Where are you from?’

It was the first time in my life anyone had ever asked me a question. I wanted to answer it, but I had no idea how to.

‘What’s the matter, boy?’ the other wave demanded brusquely. ‘Swallowed your tongue? Can’t you speak?’

I shook my head. I could listen but not speak. Neither the Minipirates nor the Hobgoblins had thought it worth my while to learn how to speak. I myself had never thought it so until that minute.

The two waves looked first at me, then at each other, with a lingering expression of profound dismay.

‘But this is awful!’ exclaimed one. ‘He can’t speak – have you ever heard of anything so frightful?’

‘Never!’ cried the other. ‘I imagine it must be even worse than evaporating!’

They circled me with a solicitous air.

‘The poor little creature! Fancy being condemned to perpetual silence! How pathetic!’

‘Honestly, it’s the most distressing thing I’ve ever seen in my life!’

‘Distressing is a pale description of my reaction to such a fate. It’s a tragedy!’

‘A classical tragedy!’

And they both began to weep bitterly.

From one moment to the next they calmed down, put their crests together, and went into a huddle.

‘I don’t feel like tormenting him.’

‘Neither do I, I’m too upset. It’s strange, but… well, somehow I feel like helping him.’

The other wave shook itself a little. ‘Yes, me too! An odd sensation, isn’t it?’

‘Very odd, but interesting too, somehow. Crazy and novel and quite unprecedented!’

‘Crazy and novel and quite unprecedented!’ the other wave repeated enthusiastically.

‘Yes, but how can we help him? What on earth can we do?’

They continued to circle my raft, deep in thought.

‘I’ve got it!’ cried the first wave. ‘We’ll teach him to speak!’

‘You think we could?’ the second wave said doubtfully. ‘He looks a bit retarded to me.’

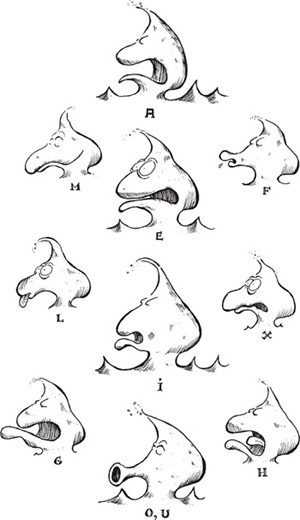

One of them sloshed right up to me. ‘Say “Ah”,’ it commanded, looking deep into my eyes and extending a seawater tongue.

‘Ah,’ I said.

‘You see!’ it cried. ‘Anyone who can say “Ah” can learn to say “binomial coefficient” in no time at all!’

![]()

I am taught to speak

In the weeks that followed, the Babbling Billows tirelessly circled my raft and taught me to speak. First I learned simple words like ‘sun’ and ‘sea’, then harder ones like ‘longitude’ and ‘circumnavigation’. I learned big words and little words, nouns and verbs, adjectives and adverbs, conjunctions and prepositions, nice words and swearwords you should never say at all. I learned how to spell and pronounce, decline and conjugate, substantivize and genitivize, accusativize and dativize. Then we got on to clauses – principal clauses and subordinate clauses, pendant clauses and relative clauses – and, finally, whole sentences.

To avoid any misapprehension, I must add that the Babbling Billows didn’t teach me to write, only to speak. The written word is redundant on the high seas. Why? Because paper gets wet too easily.

But the Babbling Billows were not content merely to teach me to speak; they wanted me to master all forms of speaking perfectly.

They taught me to murmur and maunder, gabble and prattle, whisper and bellow, converse and confabulate, and – of course – to babble like themselves. They also taught me how to deliver a speech or a soliloquy and initiated me into the art of persuasion; not only how to talk someone else to a standstill, but to talk my way out of a life or death situation. I learned to hold forth under extremely difficult conditions – standing on one leg, for instance, or doing a pawstand, or speaking with a coconut in my mouth while the Babbling Billows showered me with seawater.

Their spitefulness had long ceased to be perceptible, probably because they had never before been engaged in such a responsible and interesting activity. They became utterly engrossed in it, and I have to admit they were genuinely good teachers. Where babbling was concerned, they knew their onions.

I myself became a master of the spoken word. My progress after five weeks was such that the waves couldn’t teach me any more – indeed, I’d almost surpassed them. I could utter any given phrase at any required volume, both forwards and backwards. ‘tneiciffeoc laimoniB’ (binomial coefficient) was among the simpler ones.

I could deliver a speech, propose a toast, swear an oath (and break it), declaim a monologue, compose a verse, oil a compliment, talk drivel, blather incomprehensibly. I could speak my mind, wax indignant, sound off, wag my tongue, run people down, fire off a tirade, give a lecture, deliver a sermon, and – from now on, of course – spin a seaman’s yarn of my own.

Now that I’d learned to speak I could at last hold a conversation, though only, for the time being, with the Babbling Billows. I didn’t have much to tell them because my experience of life was so meagre, but they had plenty to impart. Anyone who had traversed the oceans for centuries, as they claimed to have done, was bound to have seen a few things in his time. They told of mighty hurricanes that drilled holes in the sea, of giant sea serpents that fought each other with jets of liquid fire, of transparent red whales that swallowed ships whole, of octopuses with miles-long tentacles capable of crushing whole islands, of water sprites that danced on the crests of waves and caught flying fish with their bare hands, of blazing meteors that made the sea boil, of continents that sank and surfaced again, of underwater volcanoes, ghost ships, foam-witches, sea-gods, wave-dwarfs, and earthquakes in the depths of the ocean. What they liked best of all, however, was to run each other down. Whenever one of them got separated from the raft, the other promptly cast aspersions on its character and urged me not to believe a word it said, et cetera. The worst of it was, I couldn’t tell them apart. They were, in fact, identical twins. For once, and in this particular case, the preconceived notion that one wave resembles another proved to be correct.

![]()

I had long become used to the two of them. You make friends quickly when you’re young, and you think things will remain the same for evermore. But a day came when the Babbling Billows’ lighthearted manner underwent a change. They had been circling the raft for several hours without uttering a word. This was unusual, and I wondered if I had done something wrong. At last they came sloshing over to the raft and proceeded to hum and haw.

‘Well, I suppose we ought to …’ said one.

‘The law of the sea, et cetera …’ snivelled the other.

Then they both began to weep.

Once they had pulled themselves together, they explained the situation to me. It seemed that a strong current had been running for some days, and the Babbling Billows knew they must follow it. If they remained in the same spot for too long, they evaporated. That was why they were doomed to roam the seas in perpetuity.

‘Many thanks for everything,’ I said, for I could speak now, of course.

‘Oh, don’t mention it,’ said one of the waves, and I could tell it was fighting back the tears.

‘I’m lost for words for the very first time,’ it went on.

I am named for life

‘We’ve got something for you,’ said the other wave. ‘A name!’

‘Yes,’ said the first wave, ‘we’re calling you Bluebear.’

The Babbling Billows obviously didn’t have much in the way of imagination, but still, I’d never had a name before. They each gave me a damp hug and sloshed off, sobbing as they went. I felt like crying myself.

I watched them making for the horizon, their silhouettes outlined against the orb of the slowly setting sun. But they perked up after only a few yards and started babbling again.

‘Now listen to me…’

‘There’s nothing you can tell me I don’t know already!’

‘That’s what you think!’

And they went on babbling. Even when darkness had fallen and they’d been out of sight for hours, I could still hear them squabbling in the distance.

My supply of coconuts was gradually running out, and my arduous language lessons had almost completely exhausted my reserves of liquid. What was more, a merciless sun had been beating down on my unprotected head for quite a while, for I was drifting ever further south.

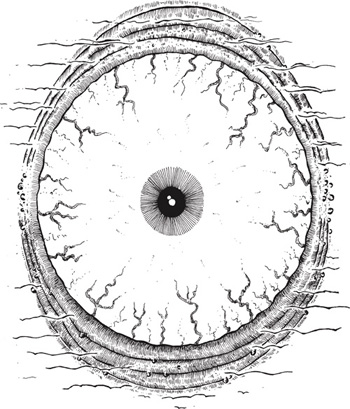

The huge eye

After three days my brain was so dehydrated that I simply sat there, torpidly contemplating the surface of the sea. If you stare at seawater for long enough, you start seeing the strangest things in the foam: wild beasts, dragons, hordes of sea monsters locked in battle, dancing water sprites, leaping mermaids, weird grey shapes equipped with horns and tails. I soon got the feeling I could see the bottom of the ocean. I glimpsed translucent palaces floating beneath me like glass submarines. I saw a kraken with a thousand tentacles, a pirate ship manned by clattering skeletons singing frightful songs. And then I saw the most terrible sight of all: a huge gargoyle of a face, ten times bigger than my raft, with a single eye the size of a house rolling around in its socket until only the white showed.

Beneath it was a mouth big enough to swallow any ship, the massive lower jaw studded with countless long, pointed teeth. The creature’s throat was gaping greedily, and looking down it was like looking into a watery grave. The face was covered with scales and horny wrinkles, small craters and deep scars. I went on staring into the water in a daze.

But I wasn’t scared by the sight. After all, it was only a figment of my desiccated imagination.

Or so I thought. But it wasn’t. It was a Tyrannomobyus Rex.

From the

‘Encyclopedia of Marvels, Life Forms

and Other Phenomena of Zamonia and its Environs’

by Professor Abdullah Nightingale

Tyrannomobyus Rex, The. A plagiostome belonging to the selachian order of fishes and related to the killer whale, the giant moray eel, the shark, the carnivorous saurian, and the cyclops. It derives its size from the whale, the conformation of its lower jaw from the moray eel, its urge to devour anything its maw can encompass from the shark, its instinctive habit of chasing anything that moves from the saurian, and its single eye from the cyclops. Over 140 feet long, the Tyrannomobyus Rex may readily be numbered among the largest predators in the world. Its skin is studded with knobs of cartilage and black as pitch, which is why it is also called the Black Whale. The head consists of a single large slab of bone that enables it to ram quite sizeable merchantmen and send them to the bottom. Fortunately, the Tyrannomobyus Rex is almost extinct. According to many experts, the specimen that has been rendering Zamonian waters unsafe for decades is the only one still in existence. Numerous whalers have tried to kill it, but none has succeeded and many have never been seen again.

I didn’t awake from my daydream until the Black Whale surfaced right in front of me. It was as if the sea had given birth to an island. Towering over my raft was a mountain of black blubber sprinkled with warts the size of boulders. Water streamed down the fatty furrows in the monster’s back and cascaded into the sea. Sucked into one of the whirlpools created around it by these waterfalls, my raft began to rotate.

The air was filled with a throat-catching stench.

I clung tightly to the mast and tried to breathe as little as possible. The whirlpools subsided, but the whale blew a gigantic fountain of water into the air, possibly as much as 300 feet high, through the vent in its head. I was so fascinated by this spectacle that I never stopped to think what its consequences might be from my own point of view.

For a moment it seemed as if the fountain had turned to ice. It hung there in front of the sun like a transparent, frozen waterfall. I could see thousands of fish in it, large and small, whole schools of cod and porpoises, a few sharks, a largish octopus, and a ship’s wheel.

Then the fountain fell back into the sea. The water descended on me like a ton of bricks. It smashed my raft to pieces and carried me down, further and further, into the depths. Fortunately, although I was surrounded by sharks, they were far too dazed to snap at me.

The pressure eased at last and I shot to the surface like a cork. Scarcely had I drawn a breath and got my bearings (I was right in front of the monster’s cyclopean eye) when it opened its mouth to gulp some more water.

In the whale’s jaws

I was brutally sucked into the whale’s jaws. I feel sure that this wasn’t directed specifically at me – indeed, I doubt if the monster had noticed me at all, not being the kind of prey that would have justified the effort. The whale was simply breathing in. Suspended from its upper lip were innumerable whiskers, the yard-long, lianalike tentacles with which it filtered its food. I managed to catch hold of one as I was swept along and clung to it while the water rushed beneath me into the creature’s maw. It wasn’t easy, for the whiskers were slippery and gave off a disgusting stench of rotting fish, but I hung on with all my might.

Having finished taking in water, the whale began to shut its mouth again. My next task was to avoid being swallowed. To achieve this I started swinging back and forth on the whisker. It would be my bad luck if the mouth closed while I was on the inside.

The lips were closing very slowly.

I swung in.

The lower lip emerged from the sea, big as a sand bank.

I swung out.

With a gurgle, the last of the water disappeared down the monster’s throat.

I swung in.

I would have done better not to venture a glance at the whale’s dark maw. Yawning beneath me was a chasm coated with dark green slime, a hissing hole filled with gastric juices. I was so scared, my strength wellnigh deserted me. Momentarily relaxing my grip, I slithered a little way down the whisker, then tightened it in the nick of time.

I swung out.

The monster’s lips shut with a snap. I had managed to finish my final swing on the outside and was now perched on the whale’s glutinous lower lip.

The cyclopean eye was rolling overhead but failed to notice me. Without giving the matter much thought, I reached for the nearest knob of gristle on the upper lip and began my ascent.

It wasn’t easy to clamber up the huge creature’s warty epidermis, but I was urged on by a courage born of despair. I climbed right past the eye, from one gristly protuberance to the next, scaled the forehead, which was a miniature mountain of black, horny skin, and made my way down into the deep wrinkles that furrowed the monster’s brow. Thereafter the going became easier. The slope was less steep, and I soon reached the foothills of the back.

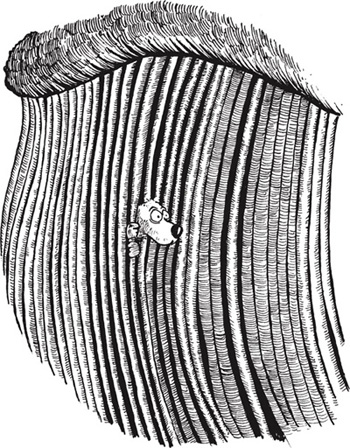

There is no polite way to describe the whale’s stench. Proliferating on its back were whole coral reefs, forests of seaweed, colonies of clams. Stranded fish were flapping everywhere, crabs and lobsters scuttling excitedly to and fro.

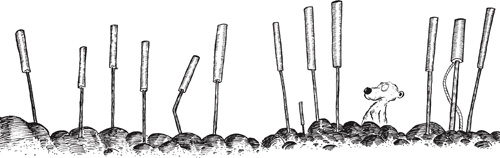

The harpoon forest

I continued to toil across the viscous surface until I came to a cluster of harpoons protruding from the whale’s gristly back. There must have been hundreds of them. Many were old and rusty, with rotting wooden shafts, but the gleaming steel barbs and brightly polished handles of others indicated that they hadn’t been there long. The harpoons were of all sizes. They ranged from normal ones that I myself could have thrown to big ones as much as fifteen feet long, which had clearly been hurled by giants, and tiny ones no bigger than a toothpick, which had probably belonged to Minipirates. Dangling from one of them, entangled in his own line, was the skeleton of a luckless whaler.

The whale was absolutely motionless now – motionless as a ship that has run aground. I took advantage of this lull to reflect on my predicament. My raft was now being digested somewhere in the Tyrannomobyus’s innards. Sooner or later the monster would dive once more, either carrying me down with it or leaving me floundering in the sea with nothing to cling to. I decided to improvise a new raft out of harpoon shafts. They were largely of wood, and still attached to many of them were corks for buoyancy and lines with which I could tie them together. My first step was to extract a brand-new harpoon some nine feet long.

A slight tremor ran through the whale’s back as I pulled it out. Not an alarming reaction, it was accompanied by a faint grunt and followed by a huge, pleasurable sigh that rang out far across the sea. The same thing happened when I extracted the next harpoon, except that the sigh was even more prolonged and pleasurable, perhaps because the harpoon was more deeply embedded.

The whale evidently liked what I was doing. I guessed I would be safe for as long as I went on removing harpoons, so I extracted one after another from the huge creature’s back, proceeding as gently and carefully as possible so as not to madden it by yanking out a barb too quickly. Within a very short time I was an expert at extracting harpoons. You have to begin by levering the shaft back and forth to loosen the barb in the gristle, and then, with a gentle, oscillating movement, pull it out.

The more carefully and skilfully I extracted the barbs from the whale’s flesh, the more pleasurable its grunts became. One huge, contented sigh after another went whooshing across the sea – an audible manifestation of the monster’s relief. I was so engrossed in my work, I never even noticed that it had got under way again. A refreshing breeze was my first indication it was very slowly propelling itself along with gentle movements of its tail. It showed no signs of being about to dive.

Removing the harpoons was hard work. Many of the barbs were so firmly embedded that it was a real struggle to get them out. The very long harpoons were lodged in the gristle more deeply and stubbornly than most, having been hurled by powerful arms. I sweated and slaved, but it made a welcome change from lolling around in idleness on the raft.

I doubt if anyone apart from me has ever heard a Tyrannomobyus Rex sigh. It’s a sound unlike any other, a sort of groan of gratitude for deliverance from years or even centuries of torment. Assemble ten thousand sea cows at the bottom of a mine shaft, persuade them to utter a simultaneous sigh of love and add the wingbeats of a million bumblebees drunk on honey, and you might produce something akin to that penetrating, contented hum.

After half a day or so my work was nearly done. I had extracted hundreds of harpoons. Only one remained, and that I removed with a certain ceremony. A final sigh of relief rang out over the sea. Tyrannomobyus Rex was harpoon-free.

I realized my mistake a moment later. By removing the last harpoon I had also disposed of the whale’s only reason for tolerating my presence on its back. It prepared to dive, as I realized when it drew a deep breath. In my eagerness I had completely lost sight of the need to build another raft. I had thoughtlessly tossed the harpoons into the sea.

Yes, the Tyrannomobyus Rex dived, but so slowly, almost gently, that I wasn’t directly endangered by its submersion. It went down by degrees, like a very big ship with a tiny leak. I slid off its back into the mirror-smooth water while the last knobs of gristle were silently engulfed. Then it disappeared altogether. A few huge bubbles rose to the surface, presumably a final farewell from its air hole.

The water was warm. I doggy-paddled around for a bit, trying to get my bearings. A few cork floats could be seen here and there. Perhaps I could collect enough of them to fashion a makeshift lifebelt. As I was swimming towards one I spotted a seagull overhead, the first I’d seen for a long time. It was flying westwards, into the setting sun.

A cloud of screaming seabirds was circling above a point on the horizon with the sun melting into the sea beyond them. A ship, or had the whale surfaced in another place? I swam towards the place. The nearer I got, the more clearly I seemed to discern a small palm forest beneath the birds. Soon I could make out a coastal strip: an immaculately white sandy beach and, beyond it, some luxuriant vegetation.

I sight land

Whether by chance or by design, the whale had dumped me near an island. Alluring scents came drifting across the sea towards me. Appetizing aromas I’d never encountered before, they included vanilla, grated nutmeg, wild garlic, and roast beef. The island smelt good. Having discovered the place, I resolved to take possession of it by right.

The sun had almost disappeared by the time I crawled ashore. I was so exhausted I simply lay down on the sand and dozed off at once. Before I finally drifted into dreamland I heard a chorus of inane giggles coming from behind the curtain of forest nearby. But I didn’t care, I had nothing to fear. Whoever they might be, those people, they were my subjects.