‘I spread my arms – and flew! No longer plunging earthwards, I circled slowly and majestically like an eagle as I made for the ground in a wide spiral. Some of the moles had already landed. Beneath me lay Grailsund, the town for whose mayor I was carrying an important message – the town where my sweetheart lived. I not only landed there as gently as a feather, I landed right on the lap of my beloved, who was sitting waiting for me in the garden. As I came in to land I felt in my pocket for the gold ring. What? I was sure I’d put it there, but no: no ring!’

My female listeners cried out in dismay.

‘Had I lost it in the quicksand? Or in the volcano? During the flight? The possibilities were legion. Panic-stricken, I rummaged around in the grains of quicksand in my trouser pocket. Nothing. No ring!’

The first handkerchiefs were being moistened. Sobs could be heard.

‘“Look in the other pocket,” advised the quicksand.

‘I felt in the other pocket, and sure enough, there it was! I removed it just before alighting on my sweetheart’s lap, and, while our lips met in a kiss, slipped it on her finger. And lo, it fitted perfectly.’

Silence. Utter silence.

The spectators were beside themselves, even the more refined among them. Seats were wrenched off their bases. The Megathon had never known such an ovation.

It was a pretty good story, admittedly, but I hadn’t been counting on such a response. What I didn’t know at the time was that I had invented the happy ending, the romantic story with an upbeat dénouement.

All Zamonian stories before my time, especially those told by congladiators, had either had no ending at all, just a punchline, or a tragic ending replete with misery, mourning, and murder. The hero died, the heroine died, the villain died, the king and queen died – together with all their subjects, of course. Every Zamonian story of the period culminated in the death of all concerned.

How Dank Was My Valley, the dramatic regional novel by Psittachus Rumplestilt, ended with all the principal characters drowned by rain. Wilfred the Wordsmith’s most widely read novel, The Roast Guest, featured twelve thousand deaths alone, and several million more occurred in his whole œuvre, most of them in the last few pages. There were writers’ schools which not only taught that the entire cast of characters in every artistic work of fiction had to die but suggested the most subtle ways of accomplishing this: with sword or glass dagger, poison or faked accident, disease or act of God. Every author vied with his confrères to devise the most bloodthirsty, tragic and corpse-strewn finales, and those who succeeded were hailed as geniuses.

Literary prizes were awarded for the novel with the most downbeat ending. In many Zamonian theatres the spectators in the first few rows wore washable clothing because most stage productions showered them with artificial blood. Any authors presumptuous enough to submit novels with non-tragic endings were booted out of their publishers’ offices.

I was satisfying a need of which my listeners had been quite unaware. Handkerchiefs were produced throughout the auditorium and tears of joy shed over my story’s happy outcome. Many spectators were embracing one another, half laughing, half weeping. Chemluth was dancing a little rain-forest jig.

Only two people showed no emotion. One was Volzotan Smyke, who simply stared at me with his cold, sharklike eyes while his toadies jabbered excitedly. The other was Nussram Fhakir the Unique. If I had impressed him, he certainly didn’t show it. He gazed impassively at the spectators and waited for them to subside. I had only won one round, after all, whereas he had ten to his credit. To repeat:

A Duel of Lies continued until one of the contestants resigned. The number of rounds and their duration were not laid down. Many rounds were over in five minutes, others lasted an hour, and there had been duels that went on for forty rounds.

Ours was destined to last ninety-nine.

Rounds 12-22

Every one of the next eleven rounds went to me. The spell had been broken, Nussram’s home advantage was forgotten, and the tide of public sentiment turned in my favour. It wasn’t that my opponent did badly. His stories were as brilliant as ever, but I always beat him by a point or two.

To be honest, I continued to gamble on the females in my audience. All my ensuing lies had a romantic flavour. They told of grand passions, eternal loyalty, lovers’ vows, dramatic partings, broken hearts. All had a happy ending, and all featured a ring. When the females applauded, their escorts applauded even more loudly to please them. After eleven stories, however, I ran out of plots that could be interwoven with the romantic bestowal of gold rings. Besides, the audience’s interest in lovesick princesses was noticeably waning.

Rounds 23-33

Sensing that his moment had come, Nussram Fhakir switched to quite another thematic field: Zamonian demonology. This was one of his specialities, as I knew from reading his autobiography. There were more demons in Zamonia than anywhere else in the world, and Atlantis had the highest concentration of them.

A lesson in Zamonian demonology

There were Mountain Demons, Earth Demons, Air Demons, Water Demons, Animal Demons, Swamp Demons, Sedge Demons, Moss Demons, Dwarf Demons, Megademons, and the aforementioned Rickshaw Demons. Even if he wasn’t a demon himself, every inhabitant of Atlantis was acquainted or friendly with, or married or related to, one or more of the creatures.

The public attitude towards demons had changed over the years. All they had done in former times was terrorize and intimidate other life forms, prowl around mainly at night, ambush travellers in forests, howl in chimneys on stormy nights, scare children, and so on. As the demon population steadily increased, however, so their mischief-making became routine. It was quite unexceptional for a Three-Tongued Moss Demon with a bloodstained axe lodged in his skull to peer over the foot of your bed, wailing like a nocturnal phantom, when you retired for the night.

People walking in the woods were no longer startled when a gnome jumped out from behind a tree and pulled awful faces at them. Not even children took fright when Coal Demons rampaged around beneath the cellar stairs. The inhabitants of Zamonia had gradually become inured to demons. No one was afraid of them any more.

The demons’ behaviour itself underwent a change. They adapted to social conventions, took ordinary jobs, and fitted into the urban scene. Before long it became commonplace to buy your bread from a demon or have one pull you through the streets in his rickshaw. There were demons in every bowling club and choral society. They swept the streets and sat on the city council. Even some of the most celebrated gebba players and congladiators were demons.

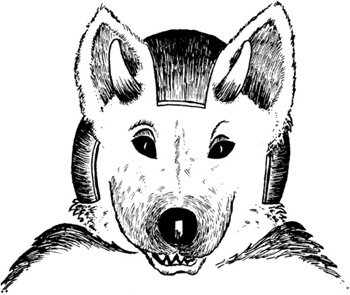

On the other hand, they were still very ugly. Contorted faces, long yellow teeth, exposed gums, rolling eyes, lolling tongues, hirsute ears, multicoloured lips, horned heads, facial warts, bristly hair – all these were typical features for which little could be done. The vainer demons made repeated attempts to remedy them, however. They had their teeth whitened and their lips bleached, tried to keep their tongues under control and refrain from rolling their eyes too wildly, concealed their horns under grotesque hats, wore tailormade clothes, and did their utmost not to be conspicuous.

Nussram exploited this social aspect in his next group of stories. They were simply dolled-up demon jokes (which were very popular in Atlantis), but he lent them an artistic gloss with a variety of demon impressions and daring political allusions, and, above all, an intimate knowledge of demonological conventions that could only have stemmed from personal experience. He imitated the lisping speech of the Rickshaw Demons, the clumsy movements of the Balinese Shadow Ghosts, the squinting eyes of the Japanese Grimacers. He had a perfect command of all their dialects, the swallowed consonants of the Grailsundian Gallowsbird, the stuttering delivery of the Gloomberg Goblin, the keening of the Irish Banshee.

Although every story was a masterpiece of parody, Nussram didn’t tread on the demons’ corns. He managed to portray their eccentricities and bizarre habits in such a sympathetic way that the numerous demons in the audience applauded him loudest of all.

My own stories were less memorable, but I stood my ground. Although six of the eleven rounds went to Nussram, I scored a respectable number of points. The level of applause for Nussram continued to be high, whereas mine was in the medium range.

Rounds 34-45

Then came a phase when fatigue set in, for the audience as well as for us. We both had to ease off a little, recoup our energy, rest and refresh our imagination. The spectators’ attention span and capacity for enthusiasm had definitely diminished. The Megathon became restive. Many of the audience stood up and regaled themselves with corn cobs and hot beer.

So the next twelve rounds were shared and the scores remained comparatively low. Neither of us registered more than five points, our stories were too feeble and the applause was too half-hearted. We both resorted to routine tricks, told new versions of old stories, picked up the thread of each other’s jokes, and marked time, narratively speaking. In an attempt to conserve our strength, we fought like weary boxers leaning on each other for a round or two.

Rounds 46-57

I managed to make up some ground in the next dozen rounds. Nussram Fhakir was showing slight but unmistakable signs of fatigue.

Reserves of energy

I now understood why Smyke had been so insistent on my losing: in the long run, the age difference was making itself felt. I was simply in better condition, with more staying power and younger vocal cords. Nussram’s lack of stamina (perceptible only to a pro) sent me into a state of restrained euphoria. We had now fought nearly sixty rounds and were roughly level on points. I was back in top form. Stories kept popping into my head as they had during my first congladiatorial contest with the Troglotroll. What was more, I bubbled over with such masses of ideas that I lumped several stories together in one round, using enough material for five, and tossed ideas around with wild abandon. The audience came to life again.

Although it was contrary to all the rules and against all common sense to be so extravagant with one’s repertoire of lies, I felt I’d tapped an inexhaustible supply. There were plenty more where those came from.

I told of my adventures on the Island of Sirens, of my ability to fashion a work of art out of any piece of wood, of the point I’d snapped off Neptune’s crown. I told of an elevator that had taken me to the centre of the earth, of collecting crocodile tears on the Amazon, and of painting the Aurora Borealis on the sky with the tail of a comet I’d ridden. I presented insights into my professional life and described how I’d worked as a star decorator, hiccup curer, equator supervisor, underwater policeman, wave comber, and tide conductor. Speaking in the strictest confidence, I informed the audience that I had been responsible for salting the oceans, icing the Polar Circle, and drying out the Demerara Desert.

I gesticulated, performed convincing impressions, made generous use of my stage voice, and twisted around on my throne to squeeze the last laugh out of my listeners, who were once more, at long last, disposed to be enthusiastic. I was rewarded for my efforts with some more maximum scores, and none of my stories obtained fewer than nine points.

Nussram, meanwhile, was looking overtired. Although he continued, on the acting level, to serve up some brilliant theatrical fictions which any younger congladiator would have envied, an expert could tell from his diminished body language that he was soft-pedalling.

My own strength abated too, not gradually but all at once. With fifty-seven rounds behind me I was ten clear rounds in the lead and should now have put on speed, but every muscle in my face hurt from talking and grimacing, my throat was parched, and my tongue was as swollen and rough as sandpaper. Worst of all, my brain had dried up.

I couldn’t think of a single idea.

And that was when Nussram Fhakir really turned up the heat.

Rounds 58-77

I hadn’t expected that. Nussram had been fooling me all the time. It was a tactical ploy. He’d leaned on the ropes, so to speak, recouped his strength, and showed me up like a greenhorn. I was completely burnt out – I had senselessly squandered my best ideas, intoxicated with the certainty of victory, whereas he seemed to be in better shape than he had been at the outset.

Nussram’s musical innovation

I had underestimated two things. In the first place, there was the immense amount of experience he’d amassed during a reign twelve times as long as mine. He had not only told thousands of stories but heard and memorized thousands more, a fund of material from which to assemble entirely new ones. Secondly, he’d enjoyed a long rest. It was six years since he’d trodden the boards, whereas I had fought one duel after another for the past year. I was finished; he was on the brink of a new beginning. He now came up with an utterly novel variant of the congladiatorial duel, a revolutionary way of presenting lies which he had devised during his self-imposed absence from the stage and now played like a trump card.

He raised his hand, and at his signal the stage was invaded by a band of Voltigorks, each armed with a bizarre instrument. I registered two troll-hide drums, two Florinthian trumboons, a crystal harp, three musical saws, two Hackonian alphorns, two vibrobasses, and a Yhôllian concertina. The musicians formed up behind Nussram’s throne and awaited his word of command.

Astonished whispers ran round the auditorium. It was neither expressly permitted nor forbidden to underscore lies with a musical accompaniment. It was simply that no one had thought of the idea.

So that was what Nussram had been up to during his mysterious absence: he had devoted himself to music and developed and trained his voice in that artistic discipline; he had devised new lies and arrayed them in musical attire. As a former admirer I couldn’t help secretly taking my hat off to him. He had reinvented the art of lying.

His first musical lie took the form of an operatic aria, with a slow, heart-rending trumboon solo overlaid by Nussram’s sonorous tenor as he sang the words in Old Zamonian. It didn’t matter that very few of the audience understood the libretto. They knew what it was about, like all arias, because the music translated the words into emotions. It dealt with great things like love, betrayal, death, and – of course – infamous lies. Nussram used the short flight of steps in front of his throne for histrionic interludes. He pranced skilfully up and down them, crawled around on them, pounded them with his fists. In conclusion he fell down them with consummate artistry, simulating his own death, and breathed his last in a deep bass voice.

I had to admit that Nussram was not only a talented singer but a gifted composer. The melodies really did have great appeal. Needless to say, he scored ten points. The audience went absolutely wild – more enthusiastic than at any other stage in the duel.

As for me, I failed even to complete my next story. I was booed to a standstill for the first time in my career. All the audience wanted was to see and hear what my opponent had devised for his next offering.

The musicians rearranged themselves. I had expected Nussram to pursue his proven operatic line still further, but his next story was a complete change in every respect: type of music, tempo, volume, even his own appearance. Discarding his congladiatorial cloak, he treated the audience to the sight of his bare chest, which was remarkably muscular for his age. This earned him a few gasps from the fair sex. Then – there’s no other way of putting it – he swept the board.

The troll-hide drummers struck up a steady rhythm, actively supported by the Voltigorks in the vibrobass section. The brutal but infectious beat made the Megathon shake. Then the musical saws came in with an electrifying melody that caused the first few spectators to stand on their seats and set even my knees twitching. Nussram, who had switched to a smoky bass register, was shaking his hips – rather inanely, in my opinion, but the audience liked it. Even the concertina’s shrillest chords enlivened the atmosphere. It was all I could do to refrain from clapping the rhythm myself and preserve a stoical demeanour. Meantime, the spectators were shaking their hips like Nussram.

This was not only an entirely different way of telling lies but a wholly new conception of music. All that had previously been known in Atlantis were tragic operas, a wide variety of folk music, and the trashy, sentimental ballads of the crooner Melliflor Gunk. This was a novelty. Nussram really did have guts: he was staking everything on a single card.

The story itself was almost unintelligible because of the din (it dealt with the acquisition of eternal youth by means of hip-shaking), and I doubted whether it could be called a lie at all, but Nussram’s success spoke for itself.

Another ten points, another deafening ovation. Me, I had only to open my mouth to be booed.

Nussram’s next mendacious tale was clearly audible because he employed a harp accompaniment only. Having donned his cloak again, he presented a musical account of the origin of the Impic Alps in a high-pitched, eunuch’s soprano. His song took the form of a fictitious saga which only just fell within the rules but was benevolently accepted by the audience. The melody was genuinely moving, albeit in a different way from the operatic aria. This time, Nussram was appealing to Zamonian love of country.

Then he proceeded to yodel. Accompanied by the Hackonian alphorns, he warbled a curiously rhythmical melody that evoked wild applause, especially from the Mountain Dwarfs present. He also underlined the beat by leaping around in a circle and slapping his thighs with the flat of his hands, a procedure spontaneously copied by the audience.

Finally, he reverted to a dramatic song that spoke of the mountains’ rosy glow and his inextinguishable love of his native land.

The Bluddums sobbed at this. It was rather too sentimental for my taste, but there was no stopping Nussram. He scored ten points.

All that remained for me was to tell my next story despite the booing.

Nussram cleared his throat and ruffled his hair so that it hung over his face in wild disarray. He took over the Yhôllian concertina and delivered the most delicate tissue of lies in a voice of which any Irish Druid would have been proud. With glassy, tearful gaze, he sang in a sobbing tremolo of his sweetheart, who had been devoured by a vicious Tyrannomobyus Rex. She was still alive in the whale’s belly, however, and regularly sent him messages in a bottle.

The Voltigorks formed a hoarse-voiced choir and joined in the refrain, which described the drinking habits of the sea gods. The audience joined in too, swaying rhythmically. The words of the song culminated in a dramatic rescue operation in the course of which Nussram not only extricated his sweetheart but strangled the whale with his bare hands. I couldn’t repress a silent, scornful laugh at this. Not so the audience. Ten points for Nussram, corn cobs and boos for me.

By now, Volzotan Smyke had relaxed completely. The stadium had never before witnessed such enthusiasm for one contestant and such scathing rejection of the other. Nussram Fhakir was staging a sensational comeback.

And so it went on for fifteen rounds, in each of which he changed his style of music, his voice, his appearance, and his narrative technique. He sang a mournful blues to the wailing saws, belted out an ecstatic war song in time to the troll-hide drums, presented operatic interludes, sang a cappella in a voice as clear as glass, played the vibrobass like a virtuoso, conducted his orchestra with lordly gestures, belaboured the crystal harp with his feet, tap-danced up and down the steps, and performed a few acrobatics of which I genuinely wouldn’t have believed him capable at his age. And he scored ten points every time. Meantime, the Bluddums had set some greasy corn cobs alight and were waving them in time to the music.

Learning to take it

I now had to display a congladiatorial quality that had never been tested in me before: the nerve to withstand boos and catcalls. Only the toughest possessed this, and many a congladiator had failed to pass the ordeal. But no duel was over until you resigned. The true congladiator showed genuine greatness when he held his ground at this, his darkest hour, and resisted the urge to run, sobbing, from the arena.

I stood there, straight as a ramrod, as the gnawed corn cobs whistled past my ears. It was the nadir of my artistic career. Everything within me itched to flee the stage and crawl into the sewers, but I stood fast and endured all that came my way: boos, catcalls, hisses, corn cobs, beer mugs – even dismantled seats and an entire Bluddum hurled bodily on to the stage by his cronies. I didn’t sit down although these humiliations were even harder to endure while standing because they turned my hind legs to jelly. I even forced myself to stand on one paw to show how little they affected me.

The audience knew that boos alone could not drive a congladiator from the stage. Negative reactions were also recorded on the meter; the louder the boos, the higher the score, so they eventually calmed down. Once you’ve passed that point, you’re over the worst. The manifestations of displeasure gradually ebbed and were replaced, first by peevish mutters and then by subdued applause. Audiences resemble wild beasts; they must first be tamed by iron will-power. Only the finest congladiators were capable of this.

Nussram knew this too, which was why my endurance earned me more respect from him than all my stories put together. He was now learning, at long last, that he’d met his match.

The applause did not begin to wane until his last five musical numbers. His two concluding vocal offerings earned him only nine and eight points respectively. After the seventy-second round his repertoire was exhausted, and he only gave encores. The spectators, tired of clapping and stamping their feet, had resumed their seats.

The Voltigork orchestra waddled off the stage, peace returned, and I bravely told my next fictitious story. The audience was ready for a quieter style of presentation. Resistance to me had largely subsided.

Rounds 78-90

Rock bottom

Our scores in the next thirteen rounds were the lowest of the duel to date. The spectators had been physically drained by Nussram’s musical interlude, and he himself was close to collapse. He had undoubtedly assumed that I would throw in the towel at some stage in his recital, but it hadn’t happened: I was still on my feet and his repertoire was exhausted. He fell back on routine stories, repeated some well-tried material, and scored minimum points. As for me, who was having to fight my way back from the brink of the abyss, I could likewise count myself lucky if I scored more than two or three points.

In the end, three low-scoring rounds went to him and ten to me. The audience was running out of enthusiasm.

‘That’s enough, that’s enough!’ chanted a handful of Yetis.

We had fought ninety rounds and won forty-five apiece. We were absolutely dead beat, both of us. Our histrionics were limited to an occasional, feeble wink or a twitch of the eyebrow.

The audience applauded out of politeness only, and none of our stories scored more than a single point. Shame forbids me to disclose their contents, but they really hit rock bottom. Our brains had been wrung dry of every last drop of imagination. Neither of us was willing to give up, of course, not after such a protracted battle. We seemed to be heading for a draw. I scanned the audience in search of inspiration. I needed something on which to base my next story.

My eye fell on Smyke, who was still regarding me coldly. He had started it all, and I couldn’t help remembering how he had laughed when I described some episodes from my past. His belief that they were elaborate lies had been the making of my congladiatorial career.

Episodes from my past…

Just a minute!

If Smyke had enjoyed them, why not the audience? He had an unerring nose for what was in demand. It wasn’t quite fair, because they weren’t fictitious at all, but who could prove that? Besides, Nussram’s musical interlude hadn’t been entirely in accordance with the rules.

Round 91

I began with the Minipirates. I described their nightly firework displays and their unsuccessful attempts to capture other vessels, my rapid growth on a diet of plankton and my ability to tie a knot in a fish. The spectators, who had almost forgotten what a good lie was, pricked up their ears. They were still in a state of lethargy, so the applause was nothing to write home about (three points), but I’d caught their attention again.

That was a beginning. The beginning of the end.

Nussram threw off his torpor with an effort. He was surprised, not having expected me to recover, but he pulled himself together and quickly stitched together a threadbare lie. It earned him two points.

Round 92

My next story dealt with Hobgoblin Island. I carefully built up the suspense in the dark, shadowy forest, then gave a vivid description of the spirits’ first appearance, imitating their frightful songs and movements. There followed a detailed account of my performances as a tear-jerking tenor and the Hobgoblins’ grisly eating habits.

A preliminary smattering of laughter and a cry of ‘Bravo!’, followed by some solid applause. Four points.

Nussram was too much of a pro to be overly impressed. Delving deep into his box of tricks, he concocted quite an ingenious double lie out of two classic fictions on which congladiators had been ringing the changes for centuries. The knowledgeable audience saw through this stratagem, however, and punished him with one measly point.

Round 93

Then came my escape by sea. My description of the Babbling Billows aroused general amusement. I imitated their voices in the thick of an argument, slopping around on my throne as I did so. I told of my vocal training and presented a few samples of my vast vocabulary. The appearance of the Tyrannomobyus Rex provided the requisite suspense, followed by a happy ending, and my account of Gourmet Island whetted the spectators’ appetite for a sequel. Back in the swing once more, they laughed uproariously and ordered hot beers. Five points.

Nussram preserved his icy calm. As nonchalant and relaxed as he had been in the first round, he spun an elegant yarn about a balloon flight to the moon. I was nonetheless struck by his incipient signs of uncertainty. Although an outsider would never have noticed such an infinitesimal hint of nerves, I detected a very slight but recurrent tremor – the top joint twitched no more than a millimetre, perhaps – in the third finger of his left hand.

Despite its neat construction, Nussram’s story was a hackneyed piece of work cobbled together out of some well-known Zamonian fairy tales. The audience graciously awarded him three points.

Round 94

My appetizing accounts of Gourmet Island led to increased corn-cob consumption, my description of the Gourmetica insularis to cries of horror, my last-minute rescue by Mac to sighs of relief. Six points.

Nussram countered, but he countered badly. I knew the story – a brilliant one, admittedly – from his autobiography. It described how he had driven Cagliostro the master charlatan off the stage and into the sewers. He had changed a few names and put the end at the beginning. That didn’t fool me, but it did fool one or two inexperienced spectators, because he notched up five points. His finger stopped twitching.

Round 95

My time with Mac the Reptilian Rescuer was made of the cloth from which all good congladiatorial stories were cut: last-minute rescues – any number of them! I told of Baldwyn’s leap from the Demon Rocks, of the Wolperting Whelps, of the headless Bollogg’s crushing of the dog farm. Frenzied applause. 7.5 points.

This visibly disconcerted Nussram Fhakir, though his discomfiture was apparent only to me and a few genuine experts in the audience, one of them being Volzotan Smyke, who shuffled around on his seat in agitation.

Nussram maintained his wooden mask of self-confidence for the audience’s benefit, but I could quite clearly see how, for a tenth of a second, the pupil of his right eye contracted by a fraction of a millimetre. The story he told was not only stolen, but stolen from me. However, he had refurbished it so skilfully that I was the only one to notice. Such was the increasing climate of enthusiasm that he scored an unmerited six points.

Round 96

My time at the Nocturnal Academy provided me with scope for extravagant boasts about my state of knowledge. I quoted at great length from the encyclopedia in my head and described the physical attributes of Professor Nightingale, Qwerty, and Fredda. Knio and Weeny slapped their thighs at this but said nothing. I edited them out of my reminiscences and proceeded straight to the maze of tunnels in the Gloomberg Mountains. I also forbore to mention the Troglotroll, preferring instead to give a detailed account of my dramatic, metamorphotic plunge into Great Forest Lake.

Eight points.

Nussram now did something that cost him a lot of good will: he rehashed my own story, substituting the Wotansgard Falls for the Gloomberg Falls and himself for me. Even my punchline was only scantily disguised.

Two points. It served him right, in my opinion.

Round 97

The Great Forest, my illusory love affair, the spider’s web, my marathon escape from the Spiderwitch… This was unbeatable stuff, and Nussram knew it.

During my performance there appeared on his brow, barely discernible with the naked eye, a tiny bead of sweat. If there were weight categories for beads of sweat, this one would undoubtedly have been classed as a flyweight. It was smaller than a bisected speck of dust, smaller perhaps than a single molecule of water. It may even have been the smallest bead of sweat in the entire history of perspiration, but I could see it, and I was sure it felt to Nussram as if it were as big and heavy as a full-grown Chimera.

As a result, his next story was not only weak in content but presented, for the very first time, with a slight tremor of uncertainty in his voice. This made itself felt on the applause meter: nine points for me, four for my opponent.

Round 98

My account of falling through the dimensions evoked gasps of astonishment at the brazen presumption of my mendacity, yet it was all true. By normal congladiatorial standards, this story was almost experimental and abstract, revolutionary and avant-garde. I mimed the state of Carefree Catalepsy and gave an impressive description of the vastness of the universe, the beauty of the Horsehead Nebula, the bizarre carpetways of the 2364th Dimension, and my return to earth by way of the dimensional hiatus from which I had left it – an impossibility in the truest sense of the word. The sheer audacity of this last assertion was an unprecedented gamble from the strategic point of view, but my quick-witted audience rewarded it with 9.5 points.

The small army of beads of sweat that now adorned Nussram’s brow were now visible to the spectators in the ringside seats. He launched into his next story, but at the very first sentence one of them trickled down his forehead and clung to his left eyebrow like a tiny, stranded mountaineer. When he tried to continue, he dislodged a whole avalanche of salty droplets. They stung his eyes, but he dared not brush them away for fear of exposing his weakness.

He faltered for the first time in his long professional career, started again from the beginning, lost his thread once more, and finally dried up in mid story. His cloak was sodden with the sweat streaming down him.

The spectators were absolutely dumbfounded. No congladiator, not even the most inexperienced apprentice, had ever failed like this before. For the first time in the annals of the Duel of Lies, there was no reaction at all, just a deathly hush. No score.

Round 99

My laborious trek through the Demerara Desert brought the audience out in a lather of sweat as well as Nussram. My vivid account of the paroxysms of mirth induced by muggrooms infected the spectators, who roared with laughter. They were equally carried away by my description of the Sharach-il-Allah, the taming of Anagrom Ataf, and life in a semi-stable mirage. I concluded with Tornado City, its population of old men, and the successful outcome of our escape attempt.

Thunderous applause. Ten points, my highest score for some time.

That was it: I’d exhausted my repertoire at last. I couldn’t recount my interlude inside the Bollogg’s head. People could have seen the Bollogg retrieve his head from Atlantis, after all, so I’d have given myself away. I have never come closer to draining the dregs of my imagination.

If Nussram had even the ghost of an idea, he would triumph. The feeblest, most desiccated idea, the lowest possible score, would be enough to defeat me.

He rose and made a dramatic, sweeping gesture of a kind he’d often made in the course of the duel when soaring to new heights after a lapse of form.

‘I’ve a very unusual announcement to make,’ he said solemnly. ‘Something quite unprecedented – something no audience has ever heard from me before.’

The old fox. The Unique. He’d dropped me in it again. I had no idea what he was going to produce from the depths of his box of tricks. Whatever it was, I would submit with good grace. He’d done it: he really was the champion.

He removed his congladiatorial cloak and, with another sweeping gesture, dropped it at my feet.

‘I resign. Well done, my boy.’

Then, head erect, he proudly strode from the stage.

The duel was over.

Pandemonium

An incredible commotion broke out. Many of the audience jumped up at once and hurried to the betting counters to collect their winnings, the rest swarmed on to the stage to carry me around the Megathon. I just caught a glimpse of Volzotan Smyke yelling at his entourage and pointing in my direction. Chemluth waved his cap excitedly. Then I was seized by the crowd.

I bobbed like a cork on a sea of hands, was tossed to and fro. This being an old congladiatorial tradition, it had to be endured. I’d experienced it often enough, but not in such a violent form. They tugged at my paws, shook me like a rag doll. The spectators were beside themselves – I was genuinely afraid of being torn limb from limb.

Four Bluddums were wrenching at my forelegs and four at my hind legs. I was on the point of being quartered when the earth began to shake.

No one took any notice at first. Tremors were an everyday occurrence in Atlantis, and this one wasn’t unduly powerful, just a rumble overlaid by the general din. Then the rumble became a low, menacing roar. The Bluddums let go of me, and I fell to the ground.

I had never known the ground to vibrate so violently. Everyone was shouting at once, and the Megathon had started to disintegrate. We could count ourselves lucky that the building had no roof, or there would probably have been some fatalities. As it was, a few columns fell over and smashed a corn-cob vendor’s stall. A few Yetis were splattered with hot fat, but Yetis were durable creatures.

The Norselanders and the Big-Footed Bertts were shouting loudest. A huge crack transected the steps and the base of the arena, engulfing dozens of seat cushions and part of the stage, complete with applause meter. A big shaft of greased lightning darted out of the fissure and disappeared into the night sky.

Then the earthquake abruptly ceased.

Someone gripped me by the shoulder.

‘Come on, we’d better get out of here, gah!’

It was Chemluth. He told me, while we were hurrying to my cubicle to collect our belongings, that Volzotan Smyke was more than a little incensed by my behaviour.

‘We must get out of Atlantis, gah. It seems you’ve lost him a whole heap of pyras.’

‘I know.’

‘You know?’

‘Yes. I’ll explain later. We’ll collect our stuff and push off, but I must change first, at least. I can’t go wandering around in my duelling outfit.’

We dashed through the gloomy catacombs under the Megathon. All the torches had gone out, probably extinguished by falling plaster or the blasts of air that issued from the ground during Atlantean earthquakes.

I pushed the door open. Chemluth lit a match and dimly illuminated the cubicle. Hastily divesting myself of my congladiator’s cloak, I pulled my clothes on.

‘What now, gah?’ asked Chemluth.

‘Search me.’

‘We don’t have any money, gah, and Smyke’s spies are everywhere. We won’t get far.’

‘Let’s take to the sewers.’

‘Join the Invisibles, you mean?’

‘Or whoever lives down there. It’s our only chance.’

Someone knocked three times. We both jumped.

Volzotan Smyke put his head round the door. ‘May we come in?’

The cubicle filled up with Yetis and Bluddums. Rumo the Wolpertinger stationed himself in the doorway and lit the room with a blazing torch.

‘Glad we caught you, my boy. We must celebrate your victory.’ Smyke’s tone was as suave as ever. ‘However, you’ll have to foot the bill for your victory party. I’m flat broke.’

I tried to explain things. ‘Listen, Smyke, it’s like this. Nussram provoked me and –’

‘I’m not only broke, oh no!’ sighed Smyke. ‘I didn’t just stake all my money on Nussram. No, no, I staked everything I owned. Buildings, businesses, stocks and shares – I’ve lost everything. And all because you refused to do me a measly little favour.’

‘Listen, Smyke, I’ll earn it all back. I’ll work for nothing …’

‘You still haven’t caught on, have you? As a congladiator, you’re all washed up. No one will challenge you after that duel tonight. You’ve defeated Nussram Fhakir. Who would take you on now? Who would bet on your opponent? Your duels have become totally uninteresting.’

I hadn’t looked at it that way.

‘Don’t worry, I’m not going to kill you. I’ve got something far more subtle in mind. You’re going to experience hell on earth. I’m sending you to the Infurno.’

The Infurno?

From the

‘Encyclopedia of Marvels, Life Forms

and Other Phenomena of Zamonia and its Environs’

by Professor Abdullah Nightingale

Infurno, The. Popular term for the mechanical innards of the SS Moloch, the gigantic ship that cruises the Zamonian Sea. It is surmised that the engine room of this legendary ocean giant is equipped with thousands of furnaces that have to be stoked incessantly to keep the vessel under way. Saunalike temperatures are reputed to prevail in the Infurno. The working environment, too, is extremely unfavourable. There is no trade union participation, for instance, and the pay is extremely employee-unfriendly. Zamonians use the term Infurno as a synonym for Hell or unpleasant living conditions (‘It was sheer Infurno!’), and unqualified persons responsible for bringing up children often threaten them with the Infurno as a way of calling them to order (‘Be good, or you’ll end up in the Infurno’).

There is no scientific proof of the Infurno’s existence because no reputable scientist has ever dared to examine the SS Moloch at close quarters.

Smyke made a dismissive gesture. ‘Put him aboard the Moloch – him and that dwarf sidekick of his!’

One of the Yetis spoke up. ‘We’re worried about our families, Smyke. The earthquake… We’d like to find out if our homes are still standing. Can’t we finish them off here and now?’

Rumo the Wolpertinger stepped forward. ‘I’ll take them to the Moloch.’

‘Good,’ said Smyke, ‘you do that. But make sure they really go aboard. I know you can’t stand Bluebear, so no little “accident” on the way, is that clear?’

‘Understood.’

Rumo the Wolpertinger

Rumo seized Chemluth and me by the scruff of the neck and hustled us along the underground passages ahead of him. He was about five feet taller than me, and his fist alone was twice the size of my head. Wolpertingers are said to be more than a match even for Werewolves, so I tried to be polite.

‘Where are you taking us?’

‘To the harbour.’

‘Are you really putting us aboard the Moloch?’

‘Shut up!’

He shoved us down a gloomy side passage – the start of the sewers. Taking an algae torch from the wall, he thrust us along in front of him.

After we had stumbled along the tunnel for a mile or two, he came to a halt.

‘There,’ he said, ‘that’s far enough.’

Far enough? Far enough for what? He’s going to kill us, I thought. He simply can’t be bothered to escort us all the way to the harbour. Chemluth adopted a flamencação stance.

For the first time ever, Rumo removed his helmet in my presence. There was a big red fleck on his forehead.

‘Know who I am?’ he asked.

‘Harvest Home Plain,’ I thought. ‘The dog farm, the Wolperting Whelps …’

I remembered the tiny puppy with the red fleck, the one we’d rescued from the Bollogg.

‘Wolpertingers never forget,’ he said. ‘You saved my life once. Now I’m saving yours.’

He extended a mighty paw. I shook his index finger.

‘Why didn’t you reveal your identity before?’

‘I knew you’d get into trouble sooner or later, I knew it the first time I saw you. It happens to everyone who gets mixed up with Smyke. Besides, you wouldn’t have believed me. It was wiser to wait.’

He peered in all directions.

‘Listen: things are happening in Atlantis – really big things. They’ve been going on for thousands of years… It won’t be long before they come to a head. Er …’

He groped for words.

‘It’s the Invisibles, they… er… how can I put it?’

He scratched his massive canine skull. Wolpertingers were handy with their fists and good at chess, but eloquence wasn’t their forte.

‘Well, I can’t really explain it, but, er… Fredda …’

‘Fredda?’ How did the Wolpertinger know Fredda?

‘Well, er… It’s all to do with the greased lightning and the earthquakes… Another planet… We’re flying and Zamonia is sinking – no, it’s the other way round. Heavens, how can I put it?’

I didn’t know either.

‘Listen, someone else will explain it to you – someone you know. You’re expected down below, in the bowels of Atlantis. I can’t take you there, I must go back and get ready for the great moment. My family… I’ve sent for someone who’ll show you the way. He should be here any minute.’

Rumo was speaking in riddles. Either he was slightly cracked, or he was deliberately trying to confuse me.

‘Gah!’ Chemluth exclaimed. ‘Someone’s coming.’

Footsteps were approaching.

‘Ah, there he is,’ said Rumo. ‘You can trust him.’

A figure emerged from the gloom. It was the Troglotroll.

‘Don’t let my resemblance to a Troglotroll mislead you into doing something rash,’ said the Troglotroll. ‘These days I’m only a Troglotroll on the outside, so to speak. Inside, I’ve been completely decontaminated, ak-ak-ak! From now on I’m your saviour.’

I tried to convey my dislike of Troglotrolls to Rumo.

‘I understand your misgivings,’ he said, ‘but I’ve personally taken steps to guarantee this troll’s change of heart.’

He bent down, seized the Troglotroll by the throat, and whispered to him, baring his teeth in an ominous way. ‘Remember what’ll happen to you if a hair of Bluebear’s head is harmed?’

‘I remember,’ the Troglotroll said humbly. The recollection clearly didn’t appeal to him.

Rumo wished us luck. Then he handed the torch to the Troglotroll and disappeared into the darkness.

Doubts about the Troglotroll

Anyone who has been led astray by a Troglotroll remains a lifelong sceptic where that labyrinth-dweller’s qualifications as a guide are concerned. The further we followed him into the bowels of Atlantis, therefore, the greater my misgivings became. We began by wading through sewers knee-deep in brackish water while green-eyed rats scurried between our legs and squeaked at us malevolently. Then we descended a long, steep, slippery flight of steps, largely overgrown with moss, that took us at least a mile into the depths. Where did it lead?

‘It’s a short cut,’ said the Troglotroll, as if he had read my thoughts. ‘These are the Invisibles’ ruins. No one ventures down here except rats and Sewer Dragons. This part of Atlantis must have originated many thousands of years ago. Nothing here is like it is on the surface, ak-ak!’

Pullulating on every side were shadowy creatures: rats, woodlice, millipedes, spiders, caterpillars, and multicoloured glow-worms that twinkled in the darkness. Bats kept fluttering around our heads. The walls streamed with moisture that seemed, in some curious way, to be flowing up them.

The tunnels became steadily bigger, and overhead, flashing at brief intervals, were blue and green lights resembling jellyfish attached to the roof by suction. We waded on through an evil-smelling soup. Something slimy wound itself around my leg.

‘Just a Snake Leech,’ the Troglotroll explained. ‘They don’t bite, they only suck a little.’

After walking for half an hour we came out in a spacious tunnel illuminated by even more roof lights. Lying at the far end was something big – something alive. It looked like a breathing mound of scales.

‘Oh!’ said the Troglotroll. ‘How unpleasant! A Sewer Dragon!’

From the

‘Encyclopedia of Marvels, Life Forms

and Other Phenomena of Zamonia and its Environs’

by Professor Abdullah Nightingale

Sewer Dragon, The. Socially debased member of the Great Lizard family [Saurii] formerly resident on the surface. A cold-blooded, forked-tongued creature of elongated stature [up to 75 feet long], it is generously equipped with teeth [as many as 900 incisors and molars] and covered with a scaly hide consisting of multicoloured plates of horny skin abounding in warty humps, crests, and folds. Sewer Dragons thrived in the marshy terrain Atlantis used to be before it dried out and became a built-up area. Unable to cope with life in the metropolis, they retreated to its extensive sewers. Sewer Dragons feed on anything assimilable by a Sewer Dragon’s efficient digestive system, which means almost anything including wood, basalt, animals, human beings, Halfway Humans, and – not to put too fine a point on it – other Sewer Dragons.

The dragon filled the whole width of the tunnel. To get past it we would have had to climb over it, and that was a course of action which only a madman would have contemplated.

‘We’ll have to climb over it,’ said the Troglotroll. He turned to us. ‘Don’t look at me as if I’m crazy, I’ve done it a hundred times. The creature’s asleep. It won’t notice a thing, ak-ak-ak!’

Sewer Dragon, The [cont.]. Sewer Dragons are somnidigestors, which means that they devote half their lives to hunting and devouring prey and the other half to digesting it in their sleep. Those who come across a sleeping Sewer Dragon can congratulate themselves on not having encountered one in its active mode. They should remain on their guard, however, because it is one of the Sewer Dragon’s predatorial techniques to pretend to be asleep.

Behind us were Smyke and all the criminals in Atlantis; ahead of us lay an omnivorous Sewer Dragon. We had a decision to make.

The Troglotroll was the first to climb on to the dragon. He marched firmly along its back.

‘You see? It’s asleep, ak-ak-ak!’ he crowed, rather too loudly for my taste.

To prove to us how soundly asleep it was, he clumped around on the creature as if it were a rocky outcrop.

‘It doesn’t notice a thing, ak-ak!’ he chortled, and jumped up and down on its back with both feet, over and over again. ‘Come on up.’

Chemluth climbed up next, followed by me. The Troglotroll was now performing a sort of tap-dance on the dragon’s scaly hide.

‘Stop it, can’t you?’ I begged him. ‘You’re making me nervous.’

‘It doesn’t notice a thing, I tell you!’ cried the Troglotroll. ‘It’s asleep!’

He leapt in the air once more and landed heavily on the dragon’s armour-plated hide. It was hard to tell whether that woke the dragon or whether it had been feigning sleep all the time. Whatever the truth, it opened its gooey, lizardlike jaws with a sound like a horse being ripped apart and uttered a startlingly human cry. Then it abruptly reared up, and Chemluth, the Troglotroll and I tumbled off its back.

Its tail lashed the tunnel like a snapped hawser. Armed with pointed, yard-long horns, the tail whistled over our heads more than once, but we ducked just in time and hugged the ground.

The Sewer Dragon drew in its tail and howled like a whipped cur. Then it hissed, emitting a jet of flame that briefly bathed the scene in a harsh glare and projected our fleeing shadows on the walls as we sprinted out of range. The creature craned its lizardlike neck and gave a furious snarl, evidently unable to turn around.

‘It’s wedged in the tunnel – too fat,’ the Troglotroll explained. ‘It’s always the same with Sewer Dragons. They eat too much. In the end they become so fat they can only move in one direction. It can only go forwards, ak-ak-ak!’

At that moment the dragon began to move backwards.

It’s incredible how fast a Sewer Dragon can travel. It simply pushed off with its powerful thighs and slithered a good twenty yards towards us along the tunnel’s sludgy floor.

Whoosh!

At the same time, it lashed its spiked tail to and fro like a flail. We ran off, but we couldn’t cover the slippery ground anything like as fast as the dragon.

Whoosh! Another twenty yards.

Whoosh! Twenty more.

The Sewer Dragon must have been perfecting this predatory technique for a very long time. It couldn’t see behind it, admittedly, so it wasn’t able to take aim, but the frequency with which it lashed its tail made up for that. Sooner or later it would hit us. It could skewer its victims on the horns and convey them to its mouth with ease.

Whoosh! Twenty yards.

Whoosh! Twenty yards.

‘See those holes in the roof?’ the Troglotroll said breathlessly during our next sprint. ‘Between the lights? We must get up there, it’s our only chance, ak-ak-ak!’

Every fifty yards or so there was a circular manhole in the roof of the tunnel, but the latter was at least twelve feet from the ground.

‘We must climb on each other’s backs,’ panted the Troglotroll. ‘The first one up can pull the others up after him.’

An utterly crackbrained idea. We would have only a few seconds in which to complete such an operation, and that was when the dragon paused between thigh-thrusts to lash the air with its tail.

‘Now!’ yelled the Troglotroll. The dragon had come to a halt.

There was no point in arguing. Chemluth had already leapt on to my shoulders.

The tail whistled past, missing us by a couple of feet at most, and cracked like a whip as it lashed thin air.

The Troglotroll climbed up me. He went about it in a terribly clumsy way, wrenching at my fur and putting his calloused feet in my face, but he managed to reach the manhole via Chemluth’s shoulders.

The Sewer Dragon was preparing to strike once more. It rolled up its tail like a licorice bootlace.

‘Quick!’ I cried. ‘Hurry up!’

The Troglotroll hauled Chemluth up. With a groan, my friend clambered through the opening.

The dragon’s tail sliced the damp air of the tunnel like a guillotine. This time it flashed past me on the left. Next time, if the creature had a system, it would aim at the centre of the tunnel.

In other words, at the place where I was standing.

It slowly rolled up its tail again.

‘Are you trying that roof trick?’ it snarled. ‘Behind my back? It wouldn’t be the first time!’

I had no idea that Sewer Dragons could speak.

Sewer Dragon, The [cont.]. Many eye-witnesses claim that Sewer Dragons are capable of articulate speech. This is impossible from the biological aspect, because they belong to the Pyrosaurian family and are dragons with short, fireproof vocal cords. There is, however, a theory that thanks to the singular electrical conditions prevailing beneath Atlantis, which may be associated with the nefarious activities of the so-called Invisibles, certain mutations have come into being.

Chemluth and the Troglotroll peered down at me through the manhole.

‘We’ve made a mistake somewhere,’ said the Troglotroll. ‘Us two are safe, but you’re still in a lot of trouble.’

‘I suppose you’re surprised I can speak,’ grunted the Sewer Dragon, ‘but I’m more surprised than anyone. I vegetated down here for centuries without saying a word, but then – crack! – one of those confounded shafts of greased lightning hit me on the head. Life has been quite different since then.’

‘You must run to the next manhole, gah!’ Chemluth whispered to me. ‘We’ll wait for you. Don’t worry, we’ll get you out!’

The dragon groaned and expelled a cloud of smoke. ‘But don’t run away with the idea that it’s made things easier for me. I couldn’t speak in the old days, but I couldn’t think either, and believe me, it’s far more agreeable not to have to brood about things.’

A sulphurous stench pervaded the tunnel. Chemluth and the Troglotroll had vanished, but I continued to stand rooted to the spot, listening to the dragon. It was showing signs of intelligence. Perhaps one could reason with it.

‘Take death, for example. I used not to have a clue when I might kick the bucket. What happy, carefree days they were! I mean, okay, so I’m a dragon with an average life expectancy of two thousand years. I’m only a thousand years old, so I’m better off than, say, a mayfly, but all the same… I used to think I was immortal, and that gives you quite another feeling, damn it all!’ The monster emitted a pathetic groan.

‘Or take pangs of conscience. I didn’t suffer from them at all in the old days. I devoured my prey and that was that. I still do today, but I feel remorseful afterwards. I wonder whether my victims had wives and children and whether they’re good for my blood pressure. All these worries are driving me mad.’ The articulate monster sighed. It was obviously in a conversational mood.

‘Then why not simply let me go?’ I suggested. ‘That’ll spare you any feelings of guilt. Besides, bear’s meat is supposed to be the worst thing for blood pressure.’

It was worth a try, I thought. What harm could it do?

‘Ah, so there you are!’ the dragon snarled viciously, and lashed out with its tail.

What a spiteful creature! It had deliberately induced me to speak so that the sound of my voice would betray where I was standing. The tip of its tail whistled straight towards me.

It was too late to turn and run, so I simply fell flat and hugged the slimy tunnel floor. The daggerlike horns scythed through the air only inches above me.

The dragon gave a disappointed snarl. ‘Hey, where are you?’

I jumped to my feet and ran off. My footsteps reechoed from the tunnel walls: splish-splash, splish-splash.

The dragon pushed off with its thighs again.

Whoosh! Twenty yards.

‘Great way of getting about, huh?’ it panted with a touch of pride. ‘That’s one of the advantages of being able to think. It would never have occurred to me in the old days.’

Whoosh! Another twenty yards.

I had almost reached the next manhole. Chemluth was hanging down into the tunnel head first, like a trapeze artist, with the Troglotroll hanging on to his legs.

‘Come on, jump, gah!’ he called. ‘We’ll haul you up!’

It was quite impossible. The Troglotroll would never manage to haul us both up at once. But in an emergency one clutches at the thinnest of straws. I jumped up and grasped Chemluth’s hands. The Troglotroll heaved and groaned.

‘I’ll never do it!’ he moaned. Our combined weight was slowly pulling him downwards. ‘You’re too heavy!’

I knew that already. All that puzzled me was why he didn’t simply let go. He could easily have escaped from the danger zone by letting go of Chemluth.

Whoosh! Another twenty yards.

The Sewer Dragon’s rear end was right beneath me. The horny plates on its armoured back were arranged in layers, like a flight of steps.

A flight of steps! How practical! I had only to walk up the dragon’s back and into the manhole! The Troglotroll pulled Chemluth up, and before the monster knew what was happening I had climbed through the hole.

‘Now run for it!’ cried the Troglotroll. ‘We’re aren’t safe yet!’

We set off. This tunnel was much narrower than the one below. Chemluth and the Troglotroll had no trouble negotiating it, but I had to run at a crouch with my head down. Behind us, the Sewer Dragon poked its head through the hole.

‘Don’t go!’ it panted. ‘We could have a nice little chat.’ It drew a deep breath.

‘Watch out,’ shouted the Troglotroll, ‘or it’ll barbecue us!’

We sprinted as fast as we could. The dragon made a gurgling noise, then spat out a jet of flame that turned the water on the tunnel walls to hissing steam. By the time it reached us, however, we were too far away: it was just a blast of very hot air. We ran into a side tunnel at the Troglotroll’s heels.

‘We’ll be safe here,’ he gasped.

We rested for a moment, leaning against the wall to catch our breath.

I couldn’t believe it: the Troglotroll had saved my life. At least, he had played an active part in my rescue and risked his own life in the process.

‘You really have turned over a new leaf,’ I said. ‘I’d never have believed it of you.’

The Troglotroll giggled. ‘I told you so, remember?’

‘What?’

‘Never trust a Troglotroll.’

In the Underworld

After about an hour’s descent into the underworld the architecture of the tunnel underwent a dramatic transformation. We entered a rectangular passage whose walls looked like shimmering metal but kept changing colour. But the genuinely alarming feature was that I’d never seen such colours before.

‘Stupid colours,’ observed the Troglotroll. ‘They’re enough to make one really nervous, ak-ak!’

The lighting now came, not from blue jellyfish, but from yellow globes that roamed the roof freely and emitted a cold, unearthly glow. Each of our footsteps was multiplied a dozen times by the echo. Long cables of many different colours ran along the walls, crackling with electricity. Located in the middle of the passage every hundred yards or so were contraptions of green glass that seemed to be muttering to themselves in some unintelligible language.

‘Those are the transistors,’ said the Troglotroll, as if that explained everything. ‘Don’t touch, please! Very electrical.’

Then the tunnel gave way to long shafts of solid, polished wood covered all over with artistically carved ornamentation and runic characters. The walls were no longer damp and the temperature had fallen to a pleasant level. It was like walking through a well-tended, well-heated museum.

When we entered one of the wooden shafts, living light seemed to accumulate around us, forming a pale bubble that accompanied our little party until we were taken over by another bubble in the next shaft. The light emitted a high-pitched, hostile humming sound that hurt my ears.

Next, we descended a curving walkway without steps, a steel spiral that wound down into the earth for about a mile. The peculiar thing about this walkway was that we didn’t have to walk on it. It conveyed us into the depths of its own accord.

Set in the walls were some big stained-glass windows like those in Atlantis’s immense cathedrals, except that their far more abstract designs resembled alien stellar systems. Pulsating behind these windows was white light.

The spiral walkway ended in front of a massive door of shiny black pyrite (or some similar mineral). Fifty feet high, it was adorned with strange-looking silver inlays.

‘Here we are,’ said the Troglotroll.

We reach our destination

He inserted his forefinger in a small, inconspicuous hole beside the door, which opened as silently as a theatre curtain going up. We stepped through the aperture into a huge hall perhaps ten times the size of the Megathon and containing what looked to me like umpteen thousands of Atlantean life forms. Venetian Midgets, Waterkins, Bluddums, Norselanders, dwarfs, gnomes, Yetis – all were milling around like the crowds on Ilstatna Boulevard during business hours, and none of them took any notice of us.

Less apprehensive now, Chemluth and I followed the Troglotroll as he swiftly threaded his way through the bustling throng. Looming over the hall were a number of gigantic machines unlike anything known to me in the field of mechanical engineering (about which, after my comprehensive education at the Nocturnal Academy, there was nothing I didn’t know).

Some consisted of dark crystals, others of rusty iron, and still others seemed to be made of polished wood with huge copper nails driven into it. From inside them came a muttering, whispering sound like that made by the smaller machines in the tunnels. The impression they made on me was one of great and reassuring beauty.

In the middle of the hall, rotating continuously, half of an immense cogwheel of high-grade steel projected through a slit in the floor. Darting around beneath the roof were harmless streaks of greased lightning of the kind we’d often seen on sultry nights in Atlantis.

Someone stuck a finger in my ear.

I spun round. It was Fredda.

Fredda giggled, looking thoroughly bashful. She was not only taller but – if such a term may be applied to an Alpine Imp – prettier. Her hair no longer stood on end; it hung down in a smoothly-combed curtain and had acquired a silky sheen. She was holding her memo pad in her hand.

Although I was suitably flabbergasted, I managed to introduce her to Chemluth. Fredda giggled even more nervously. As for Chemluth, he looked as if he had been smitten by greased lightning.

‘Gah,’ he grunted, looking mesmerized. ‘Lots of hair.’

Fredda handed me one of her memo slips, the way she used to at the Nocturnal Academy.

Hello, Bluebear, I’ve been expecting you – I’ve made the necessary arrangements. They told me you were coming.

‘How long have you been here?’ I asked. ‘What is this place, anyway?’

Fredda handed me another slip of paper.

I reached Atlantis from the Nocturnal Academy by a fairly direct route. The labyrinth presented no problem. I simply got out through one of the holes in the mountain and then climbed down it. I’m an Alpine Imp, after all.

‘But how did you get to Atlantis?’

I took the route through Southern Zamonia, which cut across the Demerara Desert for part of the way. I was making for the Impic Alps, actually, but then I sighted the Humongous Range. That was a challenge I couldn’t resist, being a mountaineer. Beyond it lay Atlantis, but I found that big-city life didn’t suit me. That’s why I went underground. And, well, here I am.

I noticed that some of the levers on one of the big machines were moving although no one was operating them. Small tools were floating through the air as if suspended on invisible wires.

Fredda handed me another slip of paper.

Those are the Invisibles. They really are invisible, you know. They came from another planet many thousands of years ago.

What could I say to that? So as not to seem too unsophisticated, I behaved as if it would take more than that to impress me.

‘But how did you find me? How did you know I was in Atlantis?’

I knew it from the very first day. It was one of the Invisibles who rescued you and your friend from the Kackertratts. He talked about it down here – said you were a bear with blue fur. That’s how I knew you were in the city.

But later on you could hardly be missed. Bluebear the King of Lies, the master congladiator! You were in all the newspapers – you were the talk of Atlantis! I even knew what you had for breakfast every day. We got our first-hand information from the Wolpertinger who escorted you part of the way. Rumo’s one of us. We have a lot of allies on the surface.

I blushed. The bombastic interviews I’d given must have sounded pretty ludicrous to someone who knew me personally. I hastily changed the subject.

‘So the rumours about the Invisibles are true. But what do they want? What exactly goes on here?’

We’re about to leave on a long journey. The longest journey ever undertaken in the biggest spaceship that ever existed.

What journey? What spaceship? And who was ‘we’? I wasn’t planning to go on any journey.

We’re taking off for the Planet of the Invisibles, and the spaceship is Atlantis itself! The Invisibles have been at work on it for thousands of years. It’ll soon be time to leave.

Just a minute! Leave me out of it! I didn’t intend to join any invisible beings on a flight to their native planet. My own planet was good enough for me, and I said as much to Fredda.

But human beings are taking over more and more of the earth. They now control nearly all the continents, leaving no room for life forms that differ from themselves. Dwarfs, gnomes, goblins, elves – they all have to live in hiding. Zamonia is the only exception – it still gives such creatures houseroom. But sooner or later Zamonia will sink into the sea, the Invisibles worked that out thousands of years ago. On their planet there’ll be plenty of room for all of us. For you as well.

The sinking business was no problem from my point of view. Being a sea-going bear, I could happily survive afloat. Human beings presented no problem either. I’d got on perfectly well with them in Tornado City.

‘I’ll need a bit of time to think it over. You don’t just go rushing into a thing like that.’

There’s no time left. I told you: we’re leaving any minute. The whole of Atlantis will soon be lifting off into space. If you don’t want to come with us you’ll have to run for it at once. You’d better make for the harbour and get aboard a ship, it’s your only chance. Personally, though, I’d advise you to come with us.

I had to make up my mind in double-quick time. I explained the situation to Chemluth, but he scarcely heard me and couldn’t take his eyes off Fredda, who was giggling, shuffling her feet, and tearing her memo slips into tiny little pieces.

‘Who is she, gah, a goddess? Such a lot of hair,’ he purred dreamily into his moustache. ‘I must be feverish, I’m feeling hot and cold at the same time …’

‘Pull yourself together,’ I told him. ‘We must make up our minds. Fredda wants us to go with her to an alien planet.’

‘An alien planet? With Fredda? Good idea, gah! Variety is the spice of life. Let’s do it! We’ll make out all right – I’ll sing, you dance. All that lovely hair!’ He treated Fredda to one of his fiery looks. He certainly couldn’t be accused of indecision or lack of daring.

I devoted the little time I had for reflection to scanning the hall. It was a scene of such great activity that no one took any notice of me. Waterkins were busy screwing up strange gadgets, Yetis appeared to be conversing with thin air (Invisibles, presumably), tools flew hither and thither, lightning flashed… To tell the truth, this was hardly the kind of crew I cared to voyage through space with.

I belonged at sea. How could I be sure the Invisibles’ planet had any seas at all?

‘Oh yes, there are seas on our planet,’ said a voice behind me.

The Invisible

I turned round. There was no one to be seen, just a small screwdriver rotating in thin air. The Invisibles took some getting used to. Were they mind-readers too?

‘Yes, we are,’ said the strange voice. It sounded like a small trumpet endowed with the power of speech. ‘Yes, we do have seas, but they consist of electricity. Everything’s electric there. I’m not sure it would suit you.’

‘Not from the sound of it, but I’m open to persuasion. What else is different on your planet?’

‘Everything, actually,’ tooted the voice. ‘We won’t try to talk you into it. All we know is, life on earth isn’t getting any easier for creatures like you. The decision is yours.’

‘Your seas consist of electricity, you say?’

‘Yes indeed. Everything’s electric. Excuse me, time is short. I have to adjust the transistors.’ The screwdriver floated off.

I decide to stay

I didn’t have to think for long. I was determined to remain on earth.

‘How do I get to the harbour?’

Fredda wasn’t sentimentally inclined, thank goodness.

It’s out of the question, I’m afraid. No one who knows the way will take you there now, it’s too late for that, and you’ll never find the way by yourself.

‘I’ll take you there,’ said the Troglotroll. ‘I still owe you one. I left you in the lurch twice but I’ve only saved your life once. Once more, and we’ll be quits, ak-ak-ak. It’s my chance to balance the books.’

Where Chemluth and Fredda were concerned, my farewells were mercifully brief for want of time.

‘We’ll send you a postcard when we get to the other planet, gah?’ said Chemluth.

He winked at me and took Fredda’s hand. They waved to me and the Troglotroll as we made our way across the great hall to the exit.

We sprinted through the sewers, vaulting over pools of viscous liquid. The harbour was already within range of our noses. It smelt of salt water and rotting fish, engine oil and freedom. Anyone else would probably have choked on the mixture, but I breathed it in like fresh mountain air.

‘We’re near the outer harbour now,’ said the Troglotroll. ‘That’s where the smaller ships drop anchor. It’s easier to get a berth on them than on the big ones. We’ll stow away if necessary.’

‘We? I thought you were going back to Atlantis.’

‘I’d sooner come with you, if you’ve no objection. I don’t know if the Invisibles are to be trusted. You can’t look them in the eye, ak-ak-ak!’

It wouldn’t be easy to sign on with the Troglotroll in tow, but I could hardly turn him down after all he’d done for me.

‘There’s a tunnel up ahead. It leads to Hulk Basin, where decommissioned vessels rot away. Once past there, we’ll be in the outer harbour.’

We climbed out of a manhole. Darkness had fallen by now, and towering over us was a massive black wall I at first mistook for a starless night sky. Then I was fiercely assailed by a familiar smell of rusty iron and hot engine oil.

‘Come!’ said a voice in my head – one I hadn’t heard for a very long time. ‘Come aboard the Moloch!’

The Troglotroll looked at me and shrugged. ‘I couldn’t help it,’ he said. ‘I’m a Troglotroll.’

Several big black hands seized me from behind and pulled a sack over my head. Then they tied up the sack and carried me off.

My life in Atlantis had been brought to a swift, surprising, and inauspicious end.