Chapter 2

How Pain Works

in Your Brain

and Nervous System

Fans of the musical My Fair Lady will remember that, when Professor Henry Higgins was trying to teach articulation to Eliza, he had her repeat the phrase, “The rain in Spain lies mainly in the plain.” Years ago, when I was first confronting the mysteries of pain, one of my mentors summarized the issue with a memorable paraphrase of that saying: “The gain in pain lies mainly in the brain.”

My mentor’s words have stuck with me because he was right. The answers to the riddle of pain are found in the brain and how it functions with regard to the body and mind. One of the immediate objectives of this book is to provide you with a greater understanding of what happens in the mind, brain, and nervous system and body in chronic pain. This knowledge will empower you and help you to better understand the confusing array of signs and symptoms that you are suffering through.

THE PAIN NETWORK IN THE BRAIN

With some eighty-six billion neurons and countless interactions between them, the human brain is far and away the most complex piece of bio-machinery on Earth. How it works is mostly a mystery, but our scientific understanding of it has increased rapidly in the last few decades because of breakthroughs in brain imaging. We can see what parts of the brain “light up” during various states of mind. The areas that are active when you feel pain are working together in what we call the pain network.

One of the most miraculous things about our brain is the way that numerous parts interact in concert with each other. In pain, for example, each area processes a different aspect of pain—such as its intensity or location—but all this information comes together to form a single experience, a unified perception. In that respect it is like a symphony orchestra. I could describe an orchestra by breaking it down to different sections: strings, horns, woodwinds, percussion—and of course the conductor. I could elaborate by describing the sounds and functions of specific instruments within those sections: oboe, viola, harp, tympani, or flute. The magic of symphonic music is the unified sound that emerges from the multitude of instruments, and the thousands of interactions between them. The whole is more than the sum of its parts.

We can understand our brain in the same way. The formation of our experience can only be understood in the context of these miraculous networks within the brain. The function of the pain network will give us a basis for understanding and treating chronic pain.

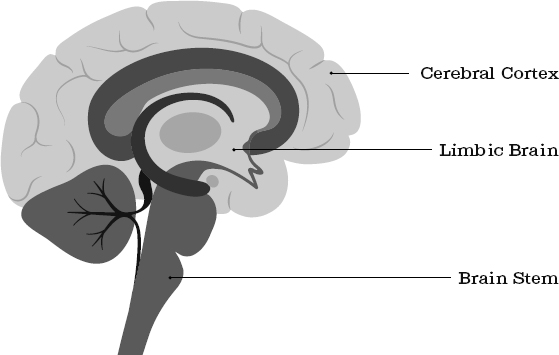

For our purposes, the brain can be divided into three main parts: brainstem, limbic system, and neocortex. The interplay of these three regions forms the neurological context of chronic pain. Their interactions also explain a lot about human behavior in general.

Brain Stem

The brain stem regulates the most fundamental life systems of the body. It controls the heartbeat, breathing, reflexes and whether one is awake or sleepy, hungry, or sated. It is the conduit for relaying both motor and sensory nerve signals from the brain to the body, and from the body back to the brain.

Limbic System

The limbic system plays a central role in forming our experience of chronic pain. The limbic system is not a separate brain structure, but rather a collection of structures that include the amygdala, hypothalamus, hippocampus, and insula. In concert they inspect and evaluate incoming sensory signals, including pain signals. The sensory information is compared to past memories and assigned an emotional value. The entire bundle of sensory and emotional information is then forwarded to other parts of the brain.

The intensity of the emotions attached to pain signals determines how disruptive the pain can be. As I mentioned earlier, the International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) defines pain as, “An unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with…actual or potential tissue damage.” The reason that pain is defined as combining sensory and emotional factors is largely due to the anatomy and physiology of structures found in the limbic system.

Through its connection to the autonomic nervous system, the limbic system affects our hormonal system, our digestion, and our perception of pain. When the limbic system perceives a threat, it seizes control of the brain stem and its autonomic functions. In a situation evaluated as dangerous, an intense fear reaction could set off a defense mechanism such as the fight-flight-or-freeze response. In a truly dangerous situation, this survival response may save our lives. But when this alarm system goes off when there is no real danger, it can contribute to chronic pain. In this and other ways, the limbic system affects how we experience pain in terms of its intensity, intrusiveness, and level of distress.

The limbic system merits special attention when it comes to understanding the experience of chronic pain. Its profound influence on the autonomic nervous system and its effects on sensory information, emotional information, and memory make it a power to be reckoned with. We will address how to address an overactive limbic system later in the book, in a section called “Limbic Retraining” (see Chapter 22 in section V).

Neocortex (Cerebral Cortex)

The neocortex is the big wrinkly covering you see when you look at a picture of a brain. The term cortex is from a Latin word meaning bark, the outermost layer. In addition to being the most prominent visible feature of the brain, it is also the most highly evolved part. It is the seat of cognition, consciousness, and language—the place where we think, imagine, and plan.

The four lobes of the cerebral cortex are responsible for three main functions:

1.Sensation

2.Motor activity

3.Association

The sensory areas of the cerebral cortex receive information from the body about touch-related sensations like pain and temperature. The motor areas are involved in initiating movement in the body. This is the source of our voluntary control over moving our arms and legs and other body parts. The association areas integrate information from multiple brain regions to form unified perceptions, rather than a random pile of sensory data. For example, the visual association cortex will take the basic aspects of a visual image—such as color, shape, and size—and put them all together to create a perception of an object that is composed of those diverse elements. Instead of seeing patches of blue and different angles from the right eye and left eye, all that information is integrated so that you see, for example, a book on a table six feet away.

At the front of the cerebral cortex, right behind your forehead, is an area called the prefrontal cortex or PFC. The PFC can help to inhibit, delay, or correct dysfunctional or impulsive reactions. It is the part of the brain that can remind you to count to ten, so you don’t lose your temper and react to something out of anger. It reminds you to take a deep breath when a strong feeling of fear overtakes you. It is the place that reminds you, when you are startled by the sound of a civil defense siren, that it’s just the monthly test of the system and not a warning of severe weather or some other emergency. In this way the “wise moderator” can assign a less threatening meaning to an event and downregulate emotional reactions.

Key Areas in the Pain Network

The components of the pain network function within and across the three main parts of the brain. Let’s turn up the detail on our microscope and take a look at some of the individual areas along the pain network to see how they contribute to our feeling of pain.

Thalamus: The Sensory Relay Center

The thalamus is the relay station of the brain. Almost all sensory information flows from the spinal cord up through the thalamus. The thalamus distributes these signals to all other parts of the brain. For example, signals go to the amygdala in the limbic system to assign emotional significance to them and to judge whether they pose a threat. The signals are also sent to sensory areas of the cerebral cortex to identify the signal in terms of sensation, pain, or temperature.

Amygdala: The Security Guard

The amygdala is the part of the brain responsible for watching out for threats. It automatically evaluates the sense data it receives from the thalamus, and attaches an emotional significance to them. It also affects memories of emotionally charged events. When the amygdala scans sensory signals that indicate danger, it can activate the autonomic nervous system.

Imagine the amygdala as a security guard whose job it is to keep an eye on a group of monitors from security cameras throughout a big building. He is constantly checking to see if anything is wrong. If a problem shows up on a monitor, such as a burglar breaking in, he will set off the alarms. The alarm triggers the fight-flight-or-freeze reaction through the autonomic nervous system.

But what if somebody plays a trick on our security guard and brings in an actor made up to look like a burglar? This security guard is easily fooled and will sound the alarm just the same.

Likewise, our amygdala sometimes signals alarm in situations that are not necessarily dangerous. People who struggle with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) suffer with this. For example, consider a soldier who has fought in combat, experiencing the horrors of war and witnessing violent injury and death. Years later, he is back home, walking down the street. He hears a car’s engine backfire, and he immediately dives for cover. His amygdala is signaling a threat where there isn’t one.

The amygdala doesn’t know the difference between an actual event and the image or memory of an event, and will create the same physiological response. It is very important to understand how this internal error affects your experience of chronic pain.

Hippocampus: Remember This

The hippocampus encodes incoming sensory information for storage in longer-term memory. It also integrates this information, combining sensations, sights, sounds, smells, and tastes. When you think about your son or daughter, the memory you retrieve of them is mixed in with various sensory data—how they look, perhaps the smell of the shampoo or cologne they use, as well as various emotions that you feel toward them. It all comes together in one package.

The hippocampus also determines which pieces of sensory information are important and worth remembering. Memories with strong emotional reactions tend to stand out. For example, you probably don’t remember what you had for lunch two weeks ago, but you likely remember where you were on September 11, 2001. This phenomenon is also true for the memory of painful sensations.

The problem for chronic pain sufferers is that the proper function of the hippocampus can be hampered by stress. That’s because it has a high concentration of receptor sites for stress hormones, such as cortisol, and other similar neurohormones. When it is under stress, the hippocampus can distort both the encoding and recall of memories. Memories of pain in a particular part of the body can be experienced and recalled differently, depending on how much the amygdala and hippocampus identify it as stressful.

Insula: Where Is My Body in Space?

The insula integrates the sensory and emotional aspects of pain perception with its sense of the body in space and control of motor movements. The combined result is our feeling of suffering as part of the pain experience. I have seen how this plays out many times, where a pain sensation will change a person’s behavior. Let’s say someone who is suffering from abdominal pain has plans to see a friend. But then they get a slight twinge of pain in their gut, so they cancel the date.

Anterior Cingulate Cortex:

Just How Bad Is this Pain?

The anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) evaluates pain sensations with a focus on the pain’s emotional aspects. Emotional responses cause the ACC to become more highly activated, which makes the pain feel worse. Research has shown that the ACC becomes more highly activated in patients with chronic pain, increasing the effect of the production of pain.

Emotion plays such a strong role in the ACC because it is highly interconnected with the amygdala and hypothalamus. This makes it a player in the regulation of emotional experience and assigning emotions to various sensations. It also increases verbal expression about the difficulty and struggle associated with a painful episode. This is why someone with chronic pain can be overwhelmed with feelings of panic, frustration, or despair after feeling a twinge of pain.