Sartre maintains that ethical values are invented, not discovered. He thinks there is no God so no divine authority on the distinction between right and wrong, and it is an act of bad faith to endorse a pre-established value system such as Christianity, humanism, or Communism. Rather, each person is radically free to create their own values through action. Ethics is something that exists only within the world of things human. Indeed, in the Existentialism and Humanism Lecture (Chapter 2 above) he says there is no universe except the human universe and we can not escape human subjectivity. We can not look outside our lives to answer the question of how to live. We can only do that by freely choosing how to live.

Superficially, Sartre might appear to be a naive relativist about morality. Relativism in morality is the thesis that it makes no sense to speak of some actions as right and some wrong, only of some individual or some society holding them to be right or wrong. Relativism embodies a mistake. From the obvious and uncontroversial historical truth that value systems vary from person to person and from society to society it is invalidly concluded that these systems can not themselves be right or wrong. It is important to refute relativism because, although it is sometimes misidentified as a liberal and tolerant doctrine, it in fact precludes our condemning individuals or regimes that practice genocide, torture, arbitrary imprisonment and other atrocities. On the relativist view these practices are, so to speak, ‘right for them but wrong for us’; a putative claim that makes no sense.

Sartre’s moral philosophy opens a conceptual space between absolute God-given morality on the one hand and naive relativism on the other. He insists that values belong only to the human world, and that we are uncomfortably free to invent them, yet he provides us with strict criteria for deciding between right and wrong.

The essential concept in the establishment of this middle path is responsibility. To say that someone is responsible for what they do is to say that they do it, they could have refrained from doing it, and they are answerable to others for doing it. (This last component of ‘responsibility’ is apparent in the word’s etymology. It means ‘answerability’.) It is a consequence of Sartre’s theses that existence precedes essence in the case of humanity, and people have an ineliminable freedom, that we are responsible for what we are. We are nothing else but what we make of ourselves. It follows that everyone is wholly and solely responsible for everything they do.

Responsibility for Sartre includes another, crucial, dimension. In choosing for myself I am implicitly choosing for others. By joining a trade union, by joining the communist party, by getting married, by becoming a Christian, by fighting in the French resistance, by anything I do, I am implicitly prescribing the same course of action to the rest of humanity. To put it another way, all my actions are recommendations. By acting I set an example for all similarly placed others to follow. I am obliged at every instant to perform actions which are examples.

This implicit recommendation to others is called in moral philosophy ‘universalisability’, and finds its most sophisticated expression in Kant’s ethical works, the Groundwork of the Metaphysics of Morals (Grundlegung zur Metaphysik der Sitten, 1785) and the Critique of Practical Reason (Kritik der Praktischen Vernunft, 1788). Kant, like Sartre, tries to found an objective morality that does not rely on theological premises. In Sartre’s texts, universalisability admits of two interpretations, one causal the other logical.

On the causal interpretation we take literally Sartre’s notion of setting an example. By joining a trade union I may cause others to join a trade union, and so my responsibility is in a direct sense a responsibility for what I make others do, not just for what I do myself.

On the logical interpretation, in order to be consistent we have to accept that persons similarly placed to ourselves should do as we do. A person is only one person amongst others and it would be inconsistent to maintain that one person but not others should follow a course of action where all those people are similarly placed. There would be something incoherent about someone who freely chose to join a trade union, or who became a convert to Christianity, but disapproved of people making just those choices. Of course Sartre accepts that that may happen. One form of religious or political commitment might be suitable for one person but not another but, prima facie, if it is right for one person to do something then it is right for any similar and similarly placed person to do the same. Being just one person rather than another can not make a moral difference.

The causal and the logical interpretations are mutually consistent. For any action, say joining the French resistance, it may both be causally efficacious in encouraging others to join, and exhibit the rule that if I join then I do not judge similarly placed others to be under no obligation to join, on pain of inconsistency.

Consistency is a condition for ethics according to Sartre. Acting immorally, that is, in a way that can not be universalised, results in incoherence. Following Kant, Sartre says the act of lying implies the universal value which it denies. Not only is there no lying without truth-telling but lying can not be universalised. The implicit recommendation to everyone to lie could never be adopted. If there was no truth-telling the distinction between lies and truth would break down and there could be no lying either. Because consistency is a constraint on morality what can not be universalised is immoral. In fashioning myself I fashion humanity as a whole.

Universalisability provides us with a test to distinguish between the rightness and the wrongness of our actions. If an action cannot be consistently universalised then it is immoral. If the action can be consistently universalised it is not immoral. In trying to resolve a moral dilemma, we have to ask what the consequences would be of everyone adopting our action as a rule.

Realising the full burden of our responsibility to humanity provokes in us the deepest sense of dread and anxiety. This discomfort is why we plunge ourselves into bad faith. Facing our freedom requires facing our responsibility. We can hardly bear to face our responsibility so we deny our freedom.

We are free and responsible despite our refusal to accept these objective facts about us. They endure through our pretence so we are in anguish.

In this way, Sartre emerges as a moral objectivist despite his rejection of theological premises for ethics. His moral philosophy is in many ways a humanistic transformation of Christian ethics. To take one conspicuous example, instead of being responsible before God a person is responsible before humanity. Instead of God watching our every action everything happens to each person as though the whole human race was watching what they are doing. Sartre’s humanity, like Christian humanity, is a fallen humanity, but Sartre’s Fall is a secular Fall. We are not fallen from any perfect natural state; we fall short of our own possibilities of acting freely and responsibly. To admit this freedom is to become committed (engagé).

The section called ‘Freedom and Responsibility’ is taken from Being and Nothingness. The section called ‘The Good and Subjectivity’ is from Notebooks for an Ethics.

Although the considerations which are about to follow are of interest primarily to the ethicist, it may nevertheless be worthwhile after these descriptions and arguments to return to the freedom of the for-itself and to try to understand what the fact of this freedom represents for human destiny.

The essential consequence of our earlier remarks is that man being condemned to be free carries the weight of the whole world on his shoulders; he is responsible for the world and for himself as a way of being. We are taking the word “responsibility” in its ordinary sense as “consciousness (of) being the incontestable author of an event or of an object.” In this sense the responsibility of the for-itself is overwhelming since he1 is the one by whom it happens that there is a world; since he is also the one who makes himself be, then whatever may be the situation in which he finds himself, the for-itself must wholly assume this situation with its peculiar coeffecient of adversity, even though it be insupportable. He must assume the situation with the proud consciousness of being the author of it, for the very worst disadvantages or the worst threats which can endanger my person have meaning only in and through my project; and it is on the ground of the engagement which I am that they appear. It is therefore senseless to think of complaining since nothing foreign has decided what we feel, what we live, or what we are.

Furthermore this absolute responsibility is not resignation; it is simply the logical requirement of the consequences of our freedom. What happens to me happens through me, and I can neither affect myself with it nor revolt against it nor resign myself to it. Moreover everything which happens to me is mine. By this we must understand first of all that I am always equal to what happens to me qua man, for what happens to a man through other men and through himself can be only human. The most terrible situations of war, the worst tortures do not create a non-human state of things; there is no non-human situation. It is only through fear, flight, and recourse to magical types of conduct that I shall decide on the non-human, but this decision is human, and I shall carry the entire responsibility for it. But in addition the situation is mine because it is the image of my free choice of myself, and everything which it presents to me is mine in that this represents me and symbolizes me. Is it not I who decide the coefficient of adversity in things and even their unpredictability by deciding myself?

Thus there are no accidents in a life; a community event which suddenly bursts forth and involves me in it does not come from the outside. If I am mobilized in a war, this war is my war; it is in my image and I deserve it. I deserve it first because I could always get out of it by suicide or by desertion; these ultimate possibles are those which must always be present for us when there is a question of envisaging a situation. For lack of getting out of it, I have chosen it. This can be due to inertia, to cowardice in the face of public opinion, or because I prefer certain other values to the value of the refusal to join in the war (the good opinion of my relatives, the honor of my family, etc.). Anyway you look at it, it is a matter of a choice. This choice will be repeated later on again and again without a break until the end of the war. Therefore we must agree with the statement by J. Romains, “In war there are no innocent victims.”2 If therefore I have preferred war to death or to dishonor, everything takes place as if I bore the entire responsibility for this war. Of course others have declared it, and one might be tempted perhaps to consider me as a simple accomplice. But this notion of complicity has only a juridical sense, and it does not hold here. For it depended on me that for me and by me this war should not exist, and I have decided that it does exist. There was no compulsion here, for the compulsion could have got no hold on a freedom. I did not have any excuse; for as we have said repeatedly in this book, the peculiar character of human-reality is that it is without excuse. Therefore it remains for me only to lay claim to this war.

But in addition the war is mine because by the sole fact that it arises in a situation which I cause to be and that I can discover it there only by engaging myself for or against it, I can no longer distinguish at present the choice which I make of myself from the choice which I make of the war. To live this war is to choose myself through it and to choose it through my choice of myself. There can be no question of considering it as “four years of vacation” or as a “reprieve,” as a “recess,” the essential part of my responsibilities being elsewhere in my married, family, or professional life. In this war which I have chosen I choose myself from day to day, and I make it mine by making myself. If it is going to be four empty years, then it is I who bear the responsibility for this.

Finally, as we pointed out earlier, each person is an absolute choice of self from the standpoint of a world of knowledges and of techniques which this choice both assumes and illumines; each person is an absolute upsurge at an absolute date and is perfectly unthinkable at another date. It is therefore a waste of time to ask what I should have been if this war had not broken out, for I have chosen myself as one of the possible meanings of the epoch which imperceptibly led to war. I am not distinct from this same epoch; I could not be transported to another epoch without contradiction. Thus I am this war which restricts and limits and makes comprehensible the period which preceded it. In this sense we may define more precisely the responsibility of the for-itself if to the earlier quoted statement, “There are no innocent victims,” we add the words, “We have the war we deserve.” Thus, totally free, undistinguishable from the period for which I have chosen to be the meaning, as profoundly responsible for the war as if I had myself declared it, unable to live without integrating it in my situation, engaging myself in it wholly and stamping it with my seal, I must be without remorse or regrets as I am without excuse; for from the instant of my upsurge into being, I carry the weight of the world by myself alone without anything or any person being able to lighten it.

Yet this responsibility is of a very particular type. Someone will say, “I did not ask to be born.” This is a naive way of throwing greater emphasis on our facticity. I am responsible for everything, in fact, except for my very responsibility, for I am not the foundation of my being. Therefore everything takes place as if I were compelled to be responsible. I am abandoned in the world, not in the sense that I might remain abandoned and passive in a hostile universe like a board floating on the water, but rather in the sense that I find myself suddenly alone and without help, engaged in a world for which I bear the whole responsibility without being able, whatever I do, to tear myself away from this responsibility for an instant. For I am responsible for my very desire of fleeing responsibilities. To make myself passive in the world, to refuse to act upon things and upon Others is still to choose myself, and suicide is one mode among others of being-in-the-world. Yet I find an absolute responsibility for the fact that my facticity (here the fact of my birth) is directly inapprehensible and even inconceivable, for this fact of my birth never appears as a brute fact but always across a projective reconstruction of my for-itself. I am ashamed of being born or I am astonished at it or I rejoice over it, or in attempting to get rid of my life I affirm that I live and I assume this life as bad. Thus in a certain sense I choose being born. This choice itself is integrally affected with facticity since I am not able not to choose, but this facticity in turn will appear only in so far as I surpass it toward my ends. Thus facticity is everywhere but inapprehensible; I never encounter anything except my responsibility. That is why I can not ask, “Why was I born?” or curse the day of my birth or declare that I did not ask to be born, for these various attitudes toward my birth—i.e., toward the fact that I realize a presence in the world—are absolutely nothing else but ways of assuming this birth in full responsibility and of making it mine. Here again I encounter only myself and my projects so that finally my abandonment—i.e., my facticity—consists simply in the fact that I am condemned to be wholly responsible for myself. I am the being which is in such a way that in its being its being is in question. And this “is” of my being is as present and inapprehensible.

Under these conditions since every event in the world can be revealed to me only as an opportunity (an opportunity made use of, lacked, neglected, etc.), or better yet since everything which happens to us can be considered as a chance (i.e., can appear to us only as a way of realizing this being which is in question in our being) and since others as transcendences-transcended are themselves only opportunities and chances, the responsibility of the for-itself extends to the entire world as a peopled-world. It is precisely thus that the for-itself apprehends itself in anguish; that is, as a being which is neither the foundation of its own being nor of the Other’s being nor of the in-itselfs which form the world, but a being which is compelled to decide the meaning of being-within it and everywhere outside of it. The one who realizes in anguish his condition as being thrown into a responsibility which extends to his very abandonment has no longer either remorse or regret or excuse; he is no longer anything but a freedom which perfectly reveals itself and whose being resides in this very revelation. But as we pointed out at the beginning of this work, most of the time we flee anguish in bad faith.

The Good has to be done. This signifies that it is the end of an act, without a doubt. But also that it does not exist apart from the act that does it. A Platonic Good that would exist in and by itself makes no sense. One would like to say that it is beyond Being, in fact it would be a Being and, as such, in the first place it would leave us completely indifferent, we would slide by it without knowing what to make of it; for another thing it would be contradictory as an aberrant synthesis of being and ought-to-be. And in parallel to the Christian Good, which has over the former the superiority of emanating from a subjectivity, if it does perhaps escape contradiction, it would still not be able to move us, for God does not do the Good: he is it. Otherwise would we have to refuse to attribute perfection to the divine essence?

What we can take from the examination of this idea that “the Good has to be done” is that the agent of Good is not the Good. Nor is he Evil, which will lead us back in an indirect way to posing the problem of the being of the Good. He is poor over against the Good, he is its disgraced creator, for his act does not turn back on him to qualify him. No doubt, if he does it often, it will be said that he is good or just. But “good” does not mean: one who possesses the Good, but: one who does it. Just does not mean: who possesses justice, but: who renders it. So the original relation of man to the Good is the same type as transcendence, that is, the Good presents itself as what has to be posited as an objective reality through the effort of a subjectivity. The Good is necessarily that toward which we transcend ourselves, it is the noema of that particular noesis that is an act. The relation between acting subjectivity and the Good is as tight as the intentional relation that links consciousness to its object, or the one that binds man to the world in being-in-the-world.

The Good cannot be conceived apart from an acting subjectivity, and yet it is beyond this subjectivity. Subjective in that it must always emanate from a subjectivity and never impose itself on this subjectivity from the outside, it is objective in that it is, in its universal essence, strictly independent of this subjectivity. And, reciprocally, any act whatsoever originally presupposes a choice of the Good. Every act, in effect, presupposes a separation and a withdrawal of the agent in relation to the real and an evaluating appraisal of what is in the name of what should be. So man has to be considered as the being through which the Good comes into the world. Not inasmuch as consciousness can be contemplative but inasmuch as the human reality is a project.

This explains why many people are tempted to confuse the Good with what takes the most effort. An ethics of effort would be absurd. In what way would effort be a sign of the Good? It would cost me more in effort to strangle my son than to live with him on good terms. Is this why I should strangle him? And if between equally certain paths that both lead to virtue I choose the more difficult, have I not confused means and ends? For what is important is to act, not to act with difficulty. And if I consider effort as a kind of ascetic exercise, I am yielding first to a naturalistic ethics of exercise, of the gymnastics of the soul. I have the thinglike [choisiste] idea of profiting from an acquisition, like the gymnast who does fifteen repetitions today so as to be able to do twenty the day after tomorrow. But in ethics there is neither trampoline nor acquisition. Everything is always new. Hero today, coward tomorrow if he is not careful. It is just that, if effort has this price in the eyes of so many (aside from an old Christian aroma of mortification), it is because in forcing myself I experience my act to a greater degree in its relation to the Good. The less I make an effort, the more the Good toward which I strive seems to me given, to exist in the manner of a thing. The more I make an effort, the more this Good that oscillates and fades and bumps along from obstacle to obstacle is something I feel myself to be making. It is in effort that the relation of subjectivity to the Good gets uncovered for me. By escaping destruction, I sense that the Good runs the risk of being destroyed along with me; each time one of my attempts miscarries, I sense that the Good is not done, that it is called into question. Effort reveals the essential fragility of the Good and the primordial importance of subjectivity.

Thus it matters little whether the Good is. What is necessary is that it be through us. Not that there is here some turning back of subjectivity on itself or that it wants to participate in the Good it posits. Reflective reversals take place after the fact and manifest nothing other than a kind of flight, a preference for oneself. Rather, simply, subjectivity finds its meaning outside of itself in this Good that never is and that it perpetually realizes. It chooses itself in choosing the Good and it cannot be that in choosing itself it does not choose the Good that defines it. For it is always through the transcendent that I define myself.

Thus, when someone accuses us of favoring whims, they are following the prejudice that would have it that man is initially fully armed, fully ready, and that thus he chooses his Good afterwards, which would leave him a freedom of indifference faced with contrary possibilities. But if man qualifies himself by his choice, caprice no longer has a meaning for, insofar as it is produced by an already constituted personality that is “in the world,” it gets inserted within an already existing choice of oneself and the Good. It is an instantaneous attention to the instant. But for there to be attention to the instant, there must be a duration that temporalizes itself, that is, an original choice of the Good and of myself in the face of the Good.

This is what allows us to comprehend that so many people devoted to the Good of a cause do not willingly accept that this Good should be realized apart from them and byways that they have not thought of. I will go so far as to sacrifice myself entirely so that the person I love finds happiness, but I do not wish that it come to him by chance and, so to speak, apart from me.

In truth, there is incertitude about subjectivity. What is certain is that the Good must be done by some human reality. But is it a question of my individual reality, of that of my party, or of that of concrete humanity? In truth, the Good being universal, if I could melt into the human totality as into an indissoluable synthesis, the ideal would be that the Good was the result of the doing of this totality. But, on the one hand, this concrete humanity is in reality a detotalized totality, that is, it will never exist as a synthesis—it is stopped along the way. With the result that the very ideal of a humanity doing the Good is impossible. But, what is more, the quality of universality of the Good necessarily implies the positing of the Other. If the Other and I were to melt into a single human reality, humanity conscious of being a unique and individual historical adventure could no longer posit the Good except as the object of its own will. Or to rediscover the universal structure of the Good, it will have to postulate other human realities, on the Moon or on the planet Mars and therefore, once again, Another person.

Note that the universal structure of the Good is necessary as that which gives it its transcendence and its objectivity. To posit the Good in doing it is to posit Others as having to do it. We cannot escape this. Thus, to conclude, it is concrete subjectivity (the isolated subject or the group, the party) that has to do the Good in the face of others, for others, and in demanding from the diversity of others that they do it too. The notion of Good demands the plurality of consciousnesses and even the plurality of commitments.

If indeed, without going so far as to presuppose the synthetic totalization of consciousnesses and the end of History, we simply imagine a unanimous accord occurring about the nature of the Good to be done and furthermore an identity of actions, the Good preserves its universality, but it loses its reality of “having-to-be-done,” for it has at present, for each concrete subjectivity, an outside. It is always for me what I have to do, but it is also what everyone else does. Which is to say that it appears as natural and as supernatural at the same time. This is, in one sense, the ambiguous reality of what are called customs. So the Good is necessarily the quest of concrete subjectivities existing in the world amidst other hostile or merely diversely oriented subjectivities. Not only is it my ideal, it is also my ideal that it become the ideal of others. Its universality is not de facto, it is de jure like its other characteristics.

It follows

1st, that no man wants the Good for the sake of the Good;

2nd, no man wants to do the Good so as to profit from it egoistically (amour-propre).

In both cases it is wrong to assume that man is initially fully made and that afterward he enters into a centripetal or centrifugal relation with the Good. Instead, since it is from this relation (which is the original choice) that both man and the Good are born, we can set aside both hypotheses. The interested man of the ethics of interest, for example, chooses, due to motivating factors that have to do with existential psychoanalysis, both to be interested and that the Good be his interest. He defines himself by this interest in the very moment that he defines the world and ethics by this interest. For me, he will never be an interested man, but rather a man who chooses to be interested. And we shall truly know what this interest is when we have made explicit the metaphysical reasons one might have for reducing the human condition to interest. At the level of his choice, the interested man is disinterested; that is, he does not explain himself in terms of an interest.

Analyze (existential psychoanalysis):

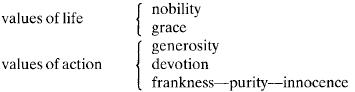

Study a few types of value:

From this it also necessarily follows that the person is inseparable from the Good he has chosen. The person is the agent of this Good. Take this Good away from him, he is nothing at all, just as if you were to take the world away from consciousness, it would no longer be consciousness of anything, therefore no longer consciousness at all. But the person does not cling to his Good to preserve himself. Instead it is in projecting himself toward his Good that he makes and preserves himself. Thus the person is the bridge between being and the ought-to-be. But as such, he is necessarily unjustifiable. This is why he chooses to hypostasize the essential characteristics of his Good in order to give this Good an ontological priority over himself. Then, existing as the servant of this a priori Good, man exists by right. He is in some way raised up by the Good to serve it. We see this clearly in religion—for God has raised up man to reflect his glory.

Paulhan speaks of the illusion of totality that makes us believe in the presence of the armadillo when we see the armadillo.4 But this illusion of totality is not just a fact of knowing something. We find it in every domain. Everything we experience, we experience as though it were our whole life and this is why across our experiences we grasp a meaning of the human condition. This sad street, with its large barracklike buildings, which I am walking along, extends out of sight for me, it is my life, it is life. And my solitude at Bordeaux was solitude, the forlornness of man.

Difficulty: there are two orders. The man in hell and the saved man. Once we allow that freedom is built up on the ground of the passions, this difficulty no longer exists: there is natural man with his determinism, and freedom appears when he escapes the infernal circle. But if you are not a Stoic, if you think that man is free even in hell, how then can you explain that there is a hell?

To put it another way, why does man almost always first choose hell, inauthenticity? Why is salvation the fruit of a new beginning neutralizing the first one? Let us consider this. What we are here calling inauthenticity is in fact the initial project or original choice man makes of himself in choosing his Good. His project is inauthentic when man’s project is to rejoin an In-itself-for-itself and to identify it with himself; in short, to be God and his own foundation, and when at the same time he posits the Good as preestablished. This project is first in the sense that it is the very structure of my existence. I exist as a choice. But as this choice is precisely the positing of a transcendent, it takes place on the unreflective plane. I cannot appear at first on the reflective plane since reflection presupposes the appearance of the reflected upon, that is, of an Erlebnis that is given always as having been there before and on the unreflective plane. Thus I am free and responsible for my project with the reservation that it is precisely as having been there first.

In fact, it is not a question of a restriction on freedom since, in reality, it is just the form in which it is freedom that is the object of this reservation. Being unreflective, this freedom does not posit itself as freedom. It posits its object (the act, the end of the act) and it is haunted by its value. At this level it realizes itself therefore as a choice of being. And it is in its very existence that it is such. Nor is it a question of a determinism or of an obligation, but rather that freedom realizes itself in the first place on the unreflective plane. And there is no sense in asking if it might first realize itself on the reflective plane since this by definition implies the unreflective. It would be equally useless to speak of a constraint on the mind of a mathematician because he, being able to conceive of a circle or a square, cannot conceive of a square circle. It is not a question of a limit which freedom trips over, but rather, in freely making itself, it does so unreflectively, and as it is a nihilating escape from being toward the In-itself-for-itself and a perpetual nihilation, it cannot do anything unless it posits the In-itself-for-itself as the Good existing as selbständig.

Whence the real problem: “can one escape from hell?” cannot be posed on any other level than the reflective level. But since reflection emanates from an already constituted freedom, there is already a question of salvation, depending on whether reflection will take up for its own account the initial project of freedom or not take it up, whether it will be a purifying reflection refusing to “go along with” this project. It is obvious that we are here in the presence of a free choice among alternatives of the type that classical psychology has habituated us to consider. “ Mitmachen oder nicht mitmachen” [to take or not to take part]. Except the two terms here do not exist before the decision. And as they take their source from the nonthetic consciousness that freedom has of itself, it is clear that accessory reflection is just the prolongation of the bad faith found nonthetically within the primitive project, whereas pure reflection is a break with this projection and the constitution of a freedom that takes itself as its end. This is why, although it would be much more advantageous to live on the plane of freedom that takes itself for its end, most people have a difficulty.…

1 I am shifting to the personal pronoun here since Sartre is describing the for-itself in concrete personal terms rather than as a metaphysical entity. Strictly speaking, of course, this is his position throughout, and the French “il” is indifferently “he” or “it.” Tr.

2 J. Romains:Les hommes debonnevolonté; “Prélude à Verdun.”

3 Sartre left for his second trip to the United States on 12 December 1945 (The Writings of Jean-Paul Sartre, p. 13). He traveled across the Atlantic by Liberty ship, a voyage that took eighteen days; hence this document, the second part of which is dated 17 December, must have been written during that voyage.

4 Jean Paulhan, Entretien sur des faits Divers (Paris: Gallimard, 1945), pp. 24–25.