How can you be sure the Bible you read is what God actually said? Remember that it was written thousands of years ago. How can you be sure it was copied correctly? Who is to say that large sections, even whole books, haven’t been left out or distorted by people adding their own ideas? Or is there evidence that the Bible we have today is a reliable reproduction of what God inspired his writers to write? Let’s explore these questions.1

We said in the first chapter that this God-inspired book called the Bible was written over a 1500-year span through more than 40 generations by more than 40 different authors from every walk of life—shepherds, soldiers, prophets, poets, monarchs, scholars, statesmen, masters, servants, tax collectors, fishermen, and tentmakers. Its God-breathed words were put down in a variety of places: in the wilderness, in a palace, in a dungeon, on a hillside, in a prison, in exile. It was penned on the continents of Asia, Africa, and Europe and was written in three languages: Hebrew, Aramaic, and Greek. It tells hundreds of stories, records hundreds of songs, and addresses hundreds of controversial subjects. Yet with all its variety of authors, origins, and content, it achieves a miraculous continuity of theme—God’s redemption of his children and the restoration of all things to his original design.

Because of the redemptive and relational purpose of the Bible, God cannot allow it to be lost, twisted, or distorted. As Jesus said, “I assure you, until heaven and earth disappear, even the smallest detail of God’s law will remain until its purpose is achieved” (Matthew 5:18 NLT). He will permit nothing to impede his purpose. “Heaven and earth will disappear,” Jesus said, “but my words will remain forever” (Matthew 24:35).

God is so passionate about his relationship with us that he has personally—and miraculously—provided the inspiration of his Word, supervised its transmission, and repeatedly reinforced its reliability so that all those who have open eyes and open hearts may believe it with assurance and confidence. Nations have rejected it, tyrants have tried to stamp it out, heretics have tried to distort it, societies have tried to discount and ignore it, but the evidence for the Bible’s reliability is sufficient to assure us and our children that it has remained a true reflection of reality—of who God is—and that “it is stronger and more permanent than heaven and earth” (Luke 16:17 NLT).

It’s not difficult to see the superintending work of God in the composition of the Old and New Testaments. Considering the process of writing and preserving manuscripts in ancient times, the fact we can be confident we have an accurate Bible is truly miraculous. None of the original manuscripts that God inspired authors to write—called autographa—are in existence today. What we read now are printed copies based on and translated from ancient handwritten copies of yet other copies of the original. This is because the Bible was composed and transmitted in an era before printing presses. All manuscripts had to be written by hand. Over time, the ink would fade, and the material it was written on would deteriorate. So if a document was to be preserved and passed down to the next generation, new copies would have to be made, else the document would be lost forever. Of course, these copies were made just like the originals—by hand with fading ink on deteriorating materials.

How can we be sure that the manuscripts available to us today are an accurate transmission of the originals?

But, you may rightly wonder, doesn’t the making of hand-copied reproductions open up the whole transmission process to error? How do we know that a weary copier, blurry-eyed from lack of sleep, didn’t skip a few critical words or leave out whole sections of Hosea or misquote some key verses? Or what if, during the copying of Mark’s Gospel some hundred years after he wrote it, some agenda-driven, meddling scribe added five chapters of his own or twisted around the things Jesus said or did? If the words God gave to Moses, David, Matthew, or Peter were later changed or carelessly copied, how could we be sure we are coming to know the one true God? How can we be confident that the commands we obey are a true reflection of God’s nature and character? What if it’s true, as some critics say, that the Bible is a collection of outdated writings that are riddled with inaccuracies and distortions? How can we be sure that the manuscripts available to us today are an accurate transmission of the originals?

God has not left us to wonder. He has miraculously supervised the transmission of his Word to ensure that it was relayed accurately from one generation to another.

One of the ways God ensured that his Word would be relayed accurately was by choosing, calling, and cultivating a nation of men and women who took the Book of the Law very seriously. God commanded and instilled in the Jewish people a great reverence for his Word. From their very first days as a nation, God told them,

Listen closely, Israel, to everything I say…Commit yourselves wholeheartedly to these commands I am giving you today. Repeat them again and again to your children. Talk about them when you are at home and when you are away on a journey, when you are lying down and when you are getting up again. Tie them to your hands as a reminder, and wear them on your forehead. Write them on the door-posts of your house and on your gates (Deuteronomy 6:3,6–9 NLT).

That attitude toward the commands of God became such a part of the Jewish identity that a class of Jewish scholars called the Sopherim, from a Hebrew word meaning “scribes,” arose between the fifth and third centuries BC. These custodians of the Hebrew Scriptures dedicated themselves to carefully preserving the ancient manuscripts and producing new copies when necessary.

The Sopherim were eclipsed by the Talmudic scribes, who guarded, interpreted, and commented on the sacred texts from about AD 100 to 500. The Talmudic scribes were followed by the better-known Masoretic scribes (about AD 500 to 900).

The Talmudic scribes, for example, established detailed and stringent disciplines for copying a manuscript. Their rules were so rigorous that when a new copy was complete, they would give the reproduction equal authority to that of its parent because they were thoroughly convinced that they had an exact duplicate.

This was the class of people who, in the providence of God, were chosen to preserve the Old Testament text for centuries. A scribe would begin his day of transcribing by ceremonially washing his entire body. He would then garb himself in full Jewish dress before sitting at his desk. As he wrote, if he came to the Hebrew name of God, he could not begin writing the name with a quill newly dipped in ink for fear it would smear the page. Once he began writing the name of God, he could not stop or allow himself to be distracted. Even if a king was to enter the room, the scribe was obligated to continue without interruption until he finished penning the holy name of the one true God.

The Talmudic guidelines for copying manuscripts also required the following:

• The scroll must be made of the skin of a ceremonially clean animal.

• Each skin must contain a specified number of columns, equal throughout the entire book.

• The length of each column must extend no less than 48 lines or more than 60 lines.

• The column breadth must consist of exactly 30 letters.

• The space of a thread must appear between every consonant.

• The breadth of nine consonants had to be inserted between each section.

• A space of three lines had to appear between each book.

• The fifth book of Moses (Deuteronomy) had to conclude exactly with a full line.

• Nothing—not even the shortest word—could be copied from memory; everything had to be copied letter by letter.

• The scribe must count the number of times each letter of the alphabet occurred in each book and compare it to the original.2

God instilled in these scribes such a painstaking reverence for the Hebrew Scriptures to ensure the amazingly accurate transmission of the Book of the Law so you and I—and our children—would have an accurate revelation of God.

Until recently, however, we had no way of knowing just how amazing the preservation of the Old Testament had been. Before 1947, the oldest complete Hebrew manuscript dated to AD 900. But with the discovery of 223 manuscripts and many more partial manuscripts and fragments in caves on the west side of the Dead Sea, we now have Old Testament manuscripts that have been dated by paleographers to around 125 BC. These Dead Sea Scrolls, as they are called, are a thousand years older than any previously known manuscripts.3

But here’s the exciting part: Once the Dead Sea Scrolls were translated and compared with modern versions, the modern Hebrew Bible proved to be identical, word for word, in more than 95 percent of the text. (The 5 percent variation consisted mainly of spelling variations. For example, of the 166 words in Isaiah 53, only 17 letters were in question. Of those, 10 letters were a matter of spelling, and 4 were stylistic changes; the remaining 3 letters comprised the word light, which was added in verse 11.)4

In other words, the greatest manuscript discovery of all time revealed that a thousand years of copying the Old Testament had produced only excruciatingly minor variations, none of which altered the clear meaning of the text or brought the manuscript’s fundamental integrity into question.

Critics will still make their pronouncements in contradiction to the evidence. However, the overwhelming weight of evidence affirms that God has preserved his Word and accurately relayed it through the centuries—so that when you pick up an Old Testament today, you can be utterly confident that you are holding a well-preserved, fully reliable document.

As you know, the Hebrew scribes did not copy the manuscripts of the New Testament. There were several reasons. The official Jewish leadership did not endorse Christianity; the letters and histories circulated by the New Testament writers were not then thought of as official Scripture; and these documents were not written in the Hebrew language, but rather in forms of Greek and Aramaic. Thus, the same formal disciplines were not followed in the transmission of these writings from one generation to another. In the case of the New Testament, God did a new thing to ensure that the blessing of his Word would be accurately preserved for us and our children.

Historians evaluate the textual reliability of ancient literature according to two standards: 1) the time interval between the original and the earliest copy; and 2) how many manuscript copies are available.

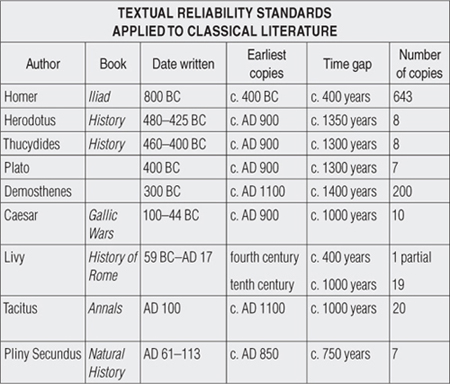

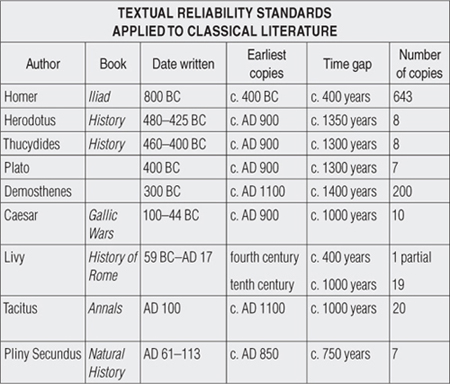

For example, virtually everything we know today about Julius Caesar’s exploits in the Gallic Wars (58 to 51 BC) is derived from ten manuscript copies of Caesar’s work The Gallic Wars. The earliest of these copies dates to a little less than a thousand years from the time the original was written. Our modern text of Livy’s History of Rome relies on 1 partial manuscript and 19 much later copies that are dated from 400 to 1000 years after the original writing (see chart below).5

By comparison, the text of Homer’s Iliad is much more reliable. It is supported by 643 manuscript copies in existence today, with a mere 400-year time gap between the date of composition and the earliest of these copies.

The textual evidence for Livy and Homer is considered more than adequate for historians to use in validating the original, but this evidence pales in comparison to what God performed in the case of the New Testament text.

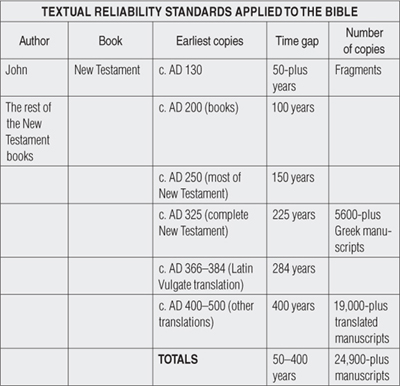

Using this accepted standard for evaluating the textual reliability of ancient writings, the New Testament stands alone. It has no equal. No other book of the ancient world can even approach its reliability. (See chart of “Textual Reliability Standards Applied to the Bible.”)6

Nearly 25,000 manuscripts or fragments of manuscripts of the New Testament repose in the libraries and universities of the world. The earliest of these discovered so far is a fragment of John’s Gospel located in the John Rylands Library of the University of Manchester, England; it has been dated to within 50 years of when the apostle John penned the original!7

Since the time the original manuscripts were written—more than 1900 years ago—many attempts have been made to refute or destroy the Bible. However, God’s Word has not only prevailed, it has also proliferated. Voltaire, the noted eighteenth-century French writer and skeptic, predicted that within a hundred years of his time Christianity would be but a footnote in history. Ironically, in 1828, 50 years after his death, the Geneva Bible Society moved into his house and began to use his printing press to produce thousands of Bibles to distribute worldwide. “People are like grass that dies away,” Peter wrote, quoting Isaiah the prophet, “but the word of the Lord will last forever” (1 Peter 1:24–25 NLT).

No other book in history has been so widely distributed in so many languages. Distribution of the Bible reaches into the billions of copies! According to the United Bible Society’s 2008 report, in that year alone, member organizations distributed 28.4 million complete Bibles and just under 300 million selections from the Bible.8 They also report that the Bible or portions of the Bible have been translated into more than 2400 languages. And amazingly, these languages represent the primary vehicles of communication for well over 90 percent of the world’s population!9

We can be confident that the text of both the Old and New Testaments has been handed down over the centuries with precision and accuracy. In other words, we can be assured that what was written down initially is what we have today. But a more basic question arises. Were the words from God recorded exactly as he intended? When these inspired writers were recording historical events, were they chronologically close to those events so that we can have confidence in the accuracy of what they wrote?

God could have spoken through anyone, from anywhere, to write his words about Christ. But to give us additional confidence in the truth, he worked through eyewitnesses.

Many ancient writings adhere only loosely to the facts of the events they report. Some highly regarded authors of the ancient world, for example, report events that took place many years before they were born and in countries they had never visited. While their accounts may be largely factual, historians admit that greater credibility must be granted to writers who are both geographically and chronologically close to the events they report.

With that in mind, look at the loving care God took when he inspired the writing of the New Testament. The overwhelming weight of scholarship confirms that the accounts of Jesus’ life, the history of the early church, and the letters that form the bulk of the New Testament were all written by men who were either eyewitnesses to the events they recorded or contemporaries of eyewitnesses. God selected Matthew, Mark, and John to write three of the four Gospels. These were men who could say such things as, “This report is from an eyewitness giving an accurate account” (John 19:35). He spoke through Luke the physician to record the third Gospel and the book of Acts. Luke, a meticulous and careful writer, used as “source material the reports circulating among us from the early disciples and other eyewitnesses of what God [did] in fulfillment of his promises” (Luke 1:2 NLT).

God could have spoken through anyone, from anywhere, to write his words about Christ. But to give us additional confidence in the truth, he worked through eyewitnesses such as John, who said, “We are telling you about what we ourselves have actually seen and heard” (1 John 1:3 NLT). He worked through Peter, who declared, “We did not follow cunningly devised fables when we made known to you the power and coming of our Lord Jesus Christ, but were eyewitnesses of His majesty” (2 Peter 1:16 NKJV). And whom did he choose as his most prolific writer? The apostle Paul, whose dramatic conversion from persecutor of Christians to planter of churches made him perhaps the most credible witness of all!

But God didn’t stop there. Those through whom he transmitted his inspired Word were also apostles. These men could rely on their own eyewitness experiences, and they could appeal to the firsthand knowledge of their contemporaries, even their most rabid opponents (see Acts 2:32; 3:15; 13:31; 1 Corinthians 15:3–8). They not only said, “Look, we saw this,” or “We heard that,” but they were also so confident in what they wrote as to say, in effect, “Check it out,” “Ask around,” and “You know it as well as I do!” Such challenges demonstrate a supreme confidence that the “God-breathed” Word was recorded exactly as God spoke it (2 Timothy 3:16 NIV).

Such careful inspiration and supervision of the Bible underlines God’s purpose—that not a single piece of this revelation about himself or the human condition be left to chance or recorded incorrectly. Ample evidence exists to suggest that he was very selective in the people he chose to record his words—they were people who for the most part had firsthand knowledge of key events and who were credible channels to record and convey exactly those truths he wanted us to know.*

God did not stop working after he had brought about the development of the massive textual evidence for the reliability of his Word. He has since worked to reinforce the evidence through external means.

A routine criterion in examining the reliability of an historical document is whether other historical material confirms or denies the internal testimony of the document itself. Historians ask, “What sources, apart from the literature under examination, substantiate its accuracy and reliability?”

In the case of the New Testament, for example, it is so extensively quoted in the ancient manuscripts of nonbiblical authors that all 27 books, from Matthew through Revelation, could be reconstructed virtually word for word, except for 11 verses.

The writings of early Christians like Eusebius (AD 339) in his Ecclesiastical History (III.39) and Irenaeus (AD 180) in his Against Heresies (Book III) reinforce the text of the apostle John’s writings. Clement of Rome (AD 95), Ignatius (AD 70–110), Polycarp (AD 70–156), and Titian (AD 170) offer external confirmation of other New Testament accounts. Non-Christian historians such as the first-century Roman historian Tacitus (AD 55–117) and the Jewish historian Josephus (AD 37–100) confirm the substance of many scriptural accounts. These and other outside sources substantiate the accuracy of the biblical record like that of no other book in history.10†

These extrabiblical references, however, are not the only external evidences that support the Bible’s reliability. The very stones cry out that God’s Word is true. Over and over again through the centuries, the reliability of the Bible has been regularly and consistently supported by archaeology. Consider the following evidences recently published in The Apologetics Study Bible for Students, of which I (Sean) was the general editor.

Until the late eighteenth century, the pursuit of biblical artifacts in the Near East was the work of amateur treasure hunters whose methods included grave-robbing. The discovery of the Rosetta Stone in Egypt by Napoleon’s army in 1799 changed everything. Biblical archaeology gradually became the domain of respected archaeologists. The discovery of ancient ruins all across the Near East has shed new light on peoples and events mentioned in Scripture. We can now better understand the customs and lifestyles that are foreign to the modern mind.

Archaeology has also established the historicity of the people and events described in the Bible, yielding over 25,000 finds that relate either directly or indirectly to Scripture. Moreover, the historical existence of some 30 individuals named in the New Testament, and nearly 60 in the Old Testament, has been confirmed through archaeological and historical research. Only a small fraction of possible biblical sites have been excavated in the Holy Land, and even regarding existing excavations, much more could be published. Nonetheless, the archaeological data we now possess, such as the examples that follow, clearly indicates that the Bible is historically reliable and is not the product of myth, superstition, or embellishment (John 3:12; 2 Peter 1:16; 1 John 1:1–2).

Ancient Corinth. Archaeological research conducted in Corinth from 1928 to 1947 startled researchers with two objects relating to Paul’s epistles to the Corinthian and Roman churches. A Latin inscription dating to about AD 50 carved into an ancient sidewalk identifies Paul’s co-laborer “Erastus” as the city treasurer (Romans 16:23). The inscription says Erastus laid a portion of sidewalk at his own expense in appreciation for being elected as treasurer. Moreover, a stone platform used to hold public lectures, official business, and trials, and to render judgments, was unearthed in 1935. It was identified as the bema seat. Bema is the same Greek word Paul used to describe the “judgment” seat of Christ (2 Corinthians 5:10) at which all Christians must appear for their rewards (1 Corinthians 3:10–17).

The Arch of Titus. When Jesus talked with his disciples on the Mount of Olives about the buildings of the temple, he said, “Do you see all these things? Truly I tell you, not one stone here will be left on another; every one will be thrown down!” (Matthew 24:2). The accuracy of Jesus’ prophecy is demonstrated by the Arch of Titus, which was constructed as a victory memorial for Emperor Titus (AD 79–81) by his younger brother Emperor Domitian (AD 81–96). Located in Rome between the ancient Forum and the Coliseum, the marble arch depicts the transportation of spoils (the menorah and sacred trumpets) from the ransacked Jerusalem temple.

In addition to this important evidence, excavations in the area of the lower street along the southwest corner of the Jerusalem Temple Mount in the 1970s revealed large stones that had been toppled from the heights by the Romans in their military campaign of AD 70. Today, none of the original building structures remain standing on the temple mount. The depictions and inscription on the Arch of Titus, as well as the rubble found at the Temple Mount in Jerusalem, provide historical verification for the fulfillment of Jesus’ prediction that the Jewish temple would be utterly destroyed.

The Babylonian Chronicles are a series of tablets with cuneiform writing that describes important events transpiring between the eighth and third centuries BC. One particular chronicle covers the period between 605–594 BC, recording the military exploits of Babylonian King Nebuchadnezzar II (605–562 BC) and his invasion of Jerusalem (2 Kings 23). It recounts how in 605 BC Nebuchadnezzar was crowned king after the death of his father, Nabopolassar. The Chronicles say that by 599 BC Nebuchadnezzar’s army advanced to Syria, continued westward to Judah, and arrived there in March 597 BC. Once there the king invaded Jerusalem, took captive King Jehoiakim (609–597 BC), and crowned his replacement King Zedekiah (597–586 BC; 2 Kings 24:10–20).

Robert Koldewey discovered more supporting evidence for these events in Babylonian ration records (595 BC), which document the food rations given to Jehoiakim and his royal family while in captivity (2 Kings 24:8–16). Additionally, hastily inscribed shards known as the Lachish Letters record Israelites’ desperate pleas in the hours immediately before Babylonian forces overwhelmed Israel’s military outposts some 25 miles outside Jerusalem. These strong archaeological evidences support the biblical record describing Jerusalem’s final days under siege by Nebuchadnezzar.

In addition to Balaam, nearly 60 other Old Testament figures have been either historically or archaeologically identified.

The Balaam inscription. The story of Balaam and his talking donkey (Numbers 22:22–40) was derided by critical scholars for many decades. Even the existence of Balaam was doubted. This view began to change in 1967, when archaeologists collected a crumbled plaster Aramaic text in the rubble of an ancient building in Deir ’Alla (Jordan). The text contains 50 lines written in faded red and black ink. The inscription reads, “Warnings from the Book of Balaam the son of Beor. He was a seer of the gods” (Numbers 22:5; Joshua 24:9). Though the building in which the text was found dates back to only the eighth century BC (during the reign of King Uzziah; see Isaiah 6:1), the condition of the plaster and ink of the text itself indicates that it is most likely much older, dating to the time of the biblical Balaam.

In addition to Balaam, nearly 60 other Old Testament figures have been either historically or archaeologically identified. These include kings David (1 Samuel 16:13), Jehu (2 Kings 9:2), Omri (1 Kings 16:22), Uzziah (Isaiah 6:1), Jotham (2 Kings 15:7), Hezekiah (Isaiah 37:1), Jehoiachin (2 Chronicles 36:8), Shalmaneser V (2 Kings 17:3), Tiglath-Pileser III (1 Chronicles 5:6), Sargon II (Isaiah 20:1), Sennacherib (Isaiah 36:1), Nebuchadnezzar (Daniel 2:1), Belshazzar (Daniel 5:1), Cyrus (Isaiah 45:1), and others.

The Ebla Tablets. Discovered by Italian archaeologist Paolo Matthiae in 1976 at Tell Mardikh in Aleppo (Syria), the Ebla Tablets represent a royal archive of over 16,000 clay tablets. Dating from 2400 BC, the records give us a glimpse into the lifestyle, vocabulary, commerce, geography, and religion of the peoples who lived near Canaan (later called Israel) in the time immediately before Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob. Translations of several tablets by Giovanni Pettinato in his Archives of Ebla: An Empire Inscribed in Clay support the existence of biblical cities such as Sodom (Genesis 19:1), Zeboiim (Genesis 14:2,8), Admah (Genesis 10:19), Hazor (1 Kings 9:15), Megiddo (1 Chronicles 7:29), Canaan (Genesis 48:4), and Jerusalem (Jeremiah 1:15).

Further, the tablets include personal names like those of biblical persons, such as Nahor (Genesis 11:22–25), Israel (Genesis 32:28), Eber (Genesis 10:21–25), Michael (Numbers 13:13), and Ishmael (Genesis 16:11). Regarding vocabulary, the tablets contain certain words similar to those used in the Bible, such as tehom, which in Genesis 1:2 is translated as “the deep.” In addition to these correspondences, the tablets provide information related to Hebrew literary style and religion, helping us to understand the civilizations in the region that became known as Israel.11

Repeatedly throughout the previous two centuries, the astounding accuracy of God’s Word has been confirmed externally. This is a very different case from that of the Book of Mormon, for example, for which there is no external support, despite much research and exploration. The external evidence for the Bible is an extremely rare phenomenon, and it makes the Bible unique compared to other religious writings of the world.

The evidence for the reliability of the Old and New Testaments is not only convincing and compelling, it is also a clear and praiseworthy indication of how God lovingly supervised its transmission. He wants you to be confident that when you discover him and his ways within the pages of his Word you are discovering the real “God who is passionate about his relationship with you” (Exodus 34:14 NLT).

* A comprehensive treatment of the internal evidence test is covered in chapters 3, 4, and 21 of Josh McDowell, The New Evidence That Demands a Verdict, rev. ed.(Nashville, TN: Thomas Nelson, 1999).

† For more information on the confirmation of the Bible’s reliability in extrabiblical sources, see chapters 3 and 4 of The New Evidence That Demands a Verdict.