TWO

Richard of Eastwell

Eastwell, with its lakeside manor house and church, is one of Kent’s best-kept secrets. It is an ancient place – with a collection of stories to match its antiquity1 – and a haven of tranquillity far removed from the bustle of Ashford only 3½ miles distant. There has been much change over the centuries – the lake was formed only in the mid-nineteenth century, the great house on the opposite side of the park is now a hotel, and the church stands in ruins – but the trees still gaze down on the spring lambs as they have for generations and there is a sense of timelessness, of being part of a scene that could belong to almost any era. Visitors to the park now walk along part of the modern North Downs Way instead of the pathways trod by their forebears, but there are still corners that a medieval or Tudor villager would find familiar were he to return today.

Eastwell belonged in late Saxon times to a thegn called Frederic, but it became part of Bishop Odo of Bayeux’s earldom of Kent after the Conquest and was granted to Hugh (Hugo) de Montfort, a Norman knight.2 The Montforts held the manor for three generations, after which it was given to the de Criol family, and then passed by marriage to the Lords Poynings, who distinguished themselves in the Hundred Years War.3 Robert, the fourth baron, died in 1446 leaving his property to his granddaughter Eleanor, de jure suo jure Baroness Poynings, who had married Henry Percy, third Earl of Northumberland, nine years earlier. Northumberland supported the House of Lancaster in the Wars of the Roses and lost both his life and his estates at Towton, but the lands were restored to his son, another Henry, in 1470. It is this Henry, the fourth earl, who is remembered principally for his inactivity at the battle of Bosworth and who was slain by his fellow northerners while trying to collect Henry VII’s taxes in 1489.

The Percies held Eastwell manor until the sixth earl of Northumberland died childless in 1537, when it was bought by three daughters and co-heiresses of Sir Christopher Hales, a trusted royal servant who had served Henry VIII as solicitor-general, attorney-general and master of the rolls. They may have intended to live there when they could dislodge the sitting tenant Sir Thomas Moyle, another prominent lawyer; but Moyle declined to vacate while he was involved in the great business of the suppression of the monasteries and eventually bought the estate from them. The Moyles had occupied the old manor house (now ‘Lake House’) for nearly a century – Sir Walter Moyle, Sir Thomas’s grandfather, had probably leased it from the Earl of Northumberland when he moved to Kent in the 1440s – and it is instructive that, although Sir Thomas could not, apparently, afford to buy the property in 1537 (at the beginning of the Dissolution), he was able to acquire it after the greater monasteries had been ransacked a few years later. He built a new mansion about half a mile to the east-north-east of Lake House, and bequeathed it to his elder daughter, Katherine, and her husband, Sir Thomas Finch, when he died in 1560. Their son, Sir Moyle Finch, was given licence to crenellate in 1589, and the estate passed on his death to his wife, Elizabeth, who was subsequently created Viscountess Maidstone and Countess of Winchilsea in her own right.

Elizabeth, who died in 1633, was the ancestress of the ten individuals who held Eastwell and the title Earl of Winchilsea for the next 260 years. We need notice only two of them: Heneage Finch, the fifth earl, whose antiquarian interests inspired much of what follows; and George William Finch-Hatton, the tenth earl, who once fought a duel with the Duke of Wellington and whose father had employed the Italian architect Joseph Bonomi to redesign and rebuild the great house around the turn of the nineteenth century. The eleventh and last earl leased the property to Prince Alfred, Duke of Edinburgh (second son of Queen Victoria), in 1874, and it became a royal residence until the Duke and his family moved to Malta twelve years later. It was sold to Lord Gerard in 1893, and had a number of other distinguished owners and tenants, including Sir John de Fonblanqua Pennefather, baronet, who again remodelled the house in 1926. The estate was bought by the Countess Midleton four years later, and was managed by her son, Captain George Brodrick, until her death in 1977. It was then sold to Thomas Bates and Sons of Essex, whose family developed the mansion as a hotel before selling to a conglomerate, which kept the house and some land but disposed of the rest to a local farmer. The hotel business was acquired by its present owners in 1993.

The church, dedicated to St Mary, was begun about 1380 and built in the Decorated and Perpendicular styles. Charles Igglesden tells us that it boasted six bells (one ancient and five presented by the tenth Earl of Winchilsea in 1842), and that the great west window had been made from ‘a collection of ancient glass, gathered from many places of note’ by the Earl’s father. Some of the fragments had been placed upside down, making them heraldically inaccurate, but among the royal coats of arms were two of Queen Elizabeth’s, one dated 1570. Edward IV’s ‘sun in splendour’ and Henry VII’s ‘crown in a thorn bush’ were also represented, and there were parts of shields of the Poynings family together with coats of arms that John Kemp (who came from nearby Wye) would have borne when he was Bishop of London (1421–5) and Archbishop of Canterbury (1452–4). Three helmets that had belonged to members of the Finch family hung on the walls, and particularly noteworthy were the ‘beautifully carved chancel screen and the pew poppy-heads’. ‘Every panel in the former is delicately worked to a design different from the others,’ wrote Igglesden, ‘while none of the numerous poppy-heads are alike.’4 The pew occupied by the Finch-Hatton family was decorated with a rebus displaying a small bird (Finch), with a hat and a tun (or cask) beneath.

St Mary’s was kept in good repair until the Second World War, although what happened then is a little uncertain. Alison Weir says that it was damaged by a V2, a long-range rocket used by the Germans, but Philip Dormer blames local British troops, whose ‘blasting, during training operations, caused plaster to fall and doors to burst open through pressure waves’.5 The real culprit may have been the chalk blocks which had been used to construct much of the interior, and which weakened as they absorbed water from the nearby lake. Early in February 1951 a workman repairing the road near the church during a gale heard a loud rumbling noise, and saw the roof collapse into the rest of the structure. Rebuilding was not an option – the parish was small and there were several churches of greater architectural interest in the immediate vicinity – and only the tower, the west wall and a small chapel in the south-western corner were left standing when the nave and chancel were dismantled in 1958. The site was cleared of rubbish with the help of parishioners and other friends of the building (see Appendix 2), and has been under the care of the ‘Friends of Friendless Churches’ since 1980. They and English Heritage have helped to preserve much of what we see today.

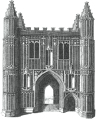

The collapse of the roof inevitably damaged parts of the interior, but some of the more valuable contents were fortunately unharmed. The bells were sold in 1952 (for around £450, according to Philip Dormer), the ancient glass was sent to King’s College, Cambridge, and other places, and the monuments, after spending some years in a purpose-built brick shelter, found a home in the Victoria and Albert Museum in 1968. These included the ornate tomb chest of Sir Thomas Moyle and his wife, Katherine, the reclining figure of Emily Georgina, second wife of the tenth earl, known as the ‘White Lady’,6 and the effigies of Sir Moyle Finch and Elizabeth, Countess of Winchilsea, finely carved in Carrara marble. Sir Moyle’s eyes are closed, but those of his wife are open, suggesting that the work was at least begun in her lifetime. It once boasted eight columns of black marble supporting an ornate canopy, but these were removed as long ago as 1756.

Lake House, which has withstood the ravages of time rather better than St Mary’s, has been described as being of ‘exceptional interest’. It is a typical small manor house measuring 45ft by 26ft 6in, built in the Norman style by John de Criol about the year 1300. Hasted’s History of Kent (1799) refers to it as the ‘court lodge’, indicating that this was where the Leet Court, which dealt with estate matters, was held before the lord or his steward. Its flint rubble walls, 2½ft thick, are pierced by four Early English windows (now blocked), and retain some of the original stone quoins. Lack of adequate foundations caused the roof to push the walls outwards, and this explains why parts of the structure had to be reinforced with massive brick buttresses and perhaps why the roof had to be rebuilt in the seventeenth century. Inside, the first-floor Norman hall and ground-level undercroft have been partitioned and ‘improved’ by the addition of fireplaces and chimneys. The latter were clearly in place by the Jacobean period, since the remaining older roof timbers are blackened by smoke from the open hearth (probably a ‘pedestal’ hearth built up 7ft from ground level so as to be flush with the hall floor), which once heated the building. Stout and enduring, it was at one time empty and semi-derelict, but is now happily a home once again.7

One day in 1542 or 1543, an elderly but plainly still active man arrived in Eastwell and made his way to Lake House. He had come, he said, because he had heard that Sir Thomas Moyle was looking for skilled bricklayers to help build his new mansion, and he was willing to offer him his services. Sir Thomas’s overseer thought him well spoken if somewhat taciturn, and engaged him after making the usual enquiries about his experience and recent employment. The newcomer, who gave his name as Richard, seemed to prefer his own company to that of the other, generally younger, workmen, but it was how he spent his leisure time that gave rise to comment and brought him to Sir Thomas’s attention when he strolled over from the old house to monitor progress. This was an age in which literacy was still confined to the upper classes, yet Richard could read Latin and enjoyed nothing better that to sit apart with a book when he had the opportunity. The implication was clearly that he and his family had once been more than bricklayers, and Sir Thomas was intrigued to discover how and why a gentleman (as he supposed) had turned to ‘trade’ to earn his keep.

We owe this report, what happened next and the ‘solution’ to the mystery to a letter written by Dr Thomas Brett, a non-juring clergyman who lived at Spring Grove, near Wye, to his friend William Warren, President of Trinity Hall, Cambridge, on 1 September 1733. Brett had resigned his livings of Betteshanger and Ruckinge on George I’s accession because his conscience would not allow him to take the oaths imposed by the government, but he remained on good terms with the Finch family and sometimes called on them at Eastwell Park. The good doctor recalled how, some thirteen years earlier (that is, about Michaelmas 1720), the then Earl of Winchilsea had told him of a tradition concerning Richard which had been handed down in his family and which his lordship apparently had no reason to question. ‘When Sir Thomas Moyle built that house (that is Eastwell Place),’ wrote Brett paraphrasing Winchilsea,

Monument to Sir Thomas and Lady Moyle, drawn in 1628.

he observed his chief bricklayer, whenever he left off work, retired with a book. Sir Thomas had a curiosity to know, what book the man read; but it was some time before he could discover it: he still putting the book up if any one came toward him. However, at last, Sir Thomas surprized him, & snatched the book from him; & looking into it, found it to be Latin. Hereupon he examined him, & finding he pretty well understood that language, he enquired, how he came by his learning? Hereupon the man told him, as he had been a good master to him, he would venture to trust him with a secret that he had never before revealed to any one. He then informed him.

That he was boarded with a Latin schoolmaster, without knowing who his parents were, ’till he was fifteen or sixteen years old; only a gentleman (who took occasion to acquaint him he was no relation to him) came once a quarter, & paid for his board, and took care to see that he wanted nothing. And one day, this gentleman took him & carried him to a fine, great house, where he passed through several stately rooms, in one of which he left him, bidding him stay there.

Then a man finely drest, with a star and garter, came to him; asked him some questions; talked kindly to him; & gave him some money. Then the ’forementioned gentleman returned, and conducted him back to his school.

Some time after the same gentleman came to him again, with a horse & proper accoutrements, & told him, he must make a journey with him into the country. They went into Leicestershire, & came to Bosworth Field; & he was carried to K. Richard III. tent. The King embraced him, & told him he was his son. But, child, says he, tomorrow I must fight for my crown. And, assure your self, if I lose that, I will lose my life too: but I hope to preserve both. Do you stand in such a place (directing him to a particular place) where you may see the battle, out of danger. And, when I have gained the victory, come to me; I will then own you to be mine, & take care of you. But, if I should be so unfortunate to lose the battel, then shift as well as you can, & take care to let nobody know that I am your father; for no mercy will be shewed to any one so [nearly] related to me. Then the king gave him a purse of gold, & dismissed him.

He followed the king’s directions. And, when he saw the battel was lost & the king killed, he hasted to London; sold his horse, & fine cloaths; &, the better to conceal himself from all suspicion of being son to a king, & that he might have means to live by his honest labour, he put himself apprentice to a bricklayer. But, having a competent skill in the Latin tongue, he was unwilling to lose it; and having an inclination also to reading, & no delight in the conversation of those he was obliged to work with, he generally spent all the time he had to spare in reading by himself.

Sir Thomas said, you are now old, and almost past your labour; I will give you the running of my kitchen as long as you live. He answered, Sir, you have a numerous family; I have been used to live retired; give me leave to build a house of one room for myself in such a field, & there, with your good leave, I will live & die: and, if you have any work I can do for you, I shall be ready to serve you. Sir Thomas granted his request, he built his house, and there continued to his death.8

Sir Thomas seems to have accepted the story, although whether he believed it or merely humoured the old man is uncertain. Richard could have sensed an opportunity to turn Moyle’s interest to his own advantage and made the tale up on the spur of the moment, but his reward, a peaceful and secure retirement, owed more to his good service than his account of his life’s history. No drawing or word-picture of the mansion they both worked to build has come down to us, but it presumably continued the fashion of constructing fortified manor houses of red brick begun in the previous century. The decoration of the walls and towers with patterns worked in contrasting blue brick (as, for example, at St John’s College, Cambridge, and at the bishop’s palace at Ely) was a skilled task that would be appropriately rewarded, and, if Richard was the master or chief bricklayer (as Brett suggests he was), his status and remuneration would have matched that of the master mason (who doubled as the architect) and the master carpenter.9 He was certainly experienced enough to occupy this position, and, although we imagined him coming to Eastwell to offer his services, it is also possible that he had been ‘head-hunted’ because his abilities were well known in the area. A master-craftsman then, whose skills commanded the respect of his colleagues, even if they thought him aloof and a little strange.

The Earl of Winchilsea was also the source for a second, slightly different, version of the story, which appeared in an anonymous work entitled The Parallel: or a Collection of Extraordinary Cases Relating to Concealed Births and Disputed Successions published in 1744. This says that in 1469 Richard, Duke of Gloucester, ‘had an amour, or for aught I know contracted a private marriage with some lady of quality . . . and towards the latter end of the same year this lady brought him a son’. The boy Richard spent the first seven years of his life being cared for by a nurse (whom he assumed was his mother) in a country village, and it was only after this that his education was entrusted to a Latin schoolmaster who resided in or near Lutterworth in Leicestershire. He developed a particular liking for the works of Horace, and was engrossed in reading one of them when Sir Thomas Moyle surprised him at Eastwell over half a century later. The rest is very similar to Dr Brett’s story, although Brett describes the matter in rather fewer words.

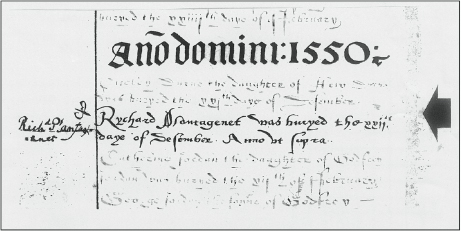

What, then, are we to make of this ‘Richard of Eastwell’ and what some would consider his rather improbable biography? The one certainty is that a man who, by the end of his life, was known as Richard Plantagenet lived for a time in the village and died there on 22 December 1550. His death is recorded in the parish register, and, although it is a copy of the original entry (made, probably, by Josias Nichols, the then rector, on 9 October 1598), there is no reason to think it a forgery. R.H. D’Elboux has commented that ‘the entries of 1538–1598 are a transcript . . . and may well have been in Latin; if so one may hazard that Plantagenet was a pedantic translation of Broom, and with the conjecture dismiss the romantic offspring of the White Boar’. But there is no evidence that the surviving register has been translated from the Latin, and the suggestion must be regarded as somewhat perverse. Similarly, it has been claimed that a mark next to the entry indicates that Richard was known to be of noble or royal blood; but this story was started in 1767 by Philip Parsons, the then rector of Eastwell, and the truth of the matter is apparently that one of the Finches placed marks against some names that were of interest to him with the intention of copying them out.10 The story depends on the tradition handed down in the Moyle and Finch families; but the fifth Earl of Winchilsea could have heard it from the third earl (d. 1689), whose grandmother, Elizabeth, had known Sir Thomas Moyle’s widow, and it would be remarkable if it was entirely without foundation. Such stories always gain and lose in the telling; but perhaps we can accept the basic premiss that Richard had not always been a humble bricklayer, and that he had a ‘past’ he preferred to conceal.

Highlighted copy of the entry in the Eastwell parish register, AD 1550. ‘Rychard Plantagenet was buryed the xxij’s daye of Desember. Anno ut supra’, with a mark in the left margin said to signify that the deceased was of noble birth.

One objection, anticipated by the author of The Parallel, is that Richard of Gloucester acknowledged two other illegitimate children, John (‘of Pomfret’) and Katherine, both born before he married Anne Neville in or after 1472. Contemporary society regarded such children as the inevitable consequence of human frailty ‘from whiche healthe of bodye, in greate prosperitye and fortune, wythoute a specyall grace hardelye refrayneth’,11 as Thomas More has it; and since Gloucester was never, so far as we know, taken to task for having sired John and Katherine, it is difficult to explain why he should be so coy about ‘Richard’. The writer suggests that this was because the year of his birth, 1469–70, was a time of great trouble for the Yorkists – Edward IV was held prisoner by Warwick the Kingmaker for some weeks and then subsequently driven into exile along with his younger brother – but if Gloucester concealed his infant son to protect him in the short term he could still have owned him after Edward recovered his kingdom in 1471. He allegedly thought little about him after Edward, his legitimate son, was born in 1475 or 1476; and it was only Edward’s death eight or nine years later that, the author suggests, caused Gloucester (who had now become King Richard III) to have young Richard brought to him for their first interview. Queen Anne’s death in March 1485 removed the last remaining obstacle to his revealing his affair with the boy’s mother, and only the verdict of Bosworth prevented Richard ‘Plantagenet’ from being publicly acknowledged as the King’s son.

It almost goes without saying that, if Queen Anne knew of the existence of John and Katherine, she would not have been particularly scandalised by the revelation that her husband had a third such child, and the secrecy that surrounded ‘Richard’ cannot be explained in these terms. It is also most unlikely that a boy who was placed in the care of a schoolmaster when he was 7 would still be living with the same schoolmaster (and, presumably, still learning his lessons) when he was 15 or 16. Children were typically sent away from home when they were 7 or 8 (to develop self-reliance and to make useful contacts rather than to prevent their parents from becoming too fond of them in case they died early), but maturity came quickly and they entered the adult world in their early teens. Not all of them could, or would, wish to emulate Henry Percy (Hotspur), who was commanding troops when he was only 12; but Richard of Gloucester’s own formal tutelage had ended at this age, and John of Pomfret, young Richard’s half-brother, cannot have been much older when his father named him Captain of Calais in September 1483.12 Richard had also reached an age when he could perform useful service, and would almost certainly have been trained for whatever role Gloucester had in mind for him long before he reached 15 or 16. The implication is that he had not yet embarked on such training and was therefore several years younger than he claimed to be.

So far so good, but could a youth who was perhaps only 11 or 12 have made his own way to London and decided to apprentice himself to a bricklayer? It seems remarkable that, having been brought to his father at Bosworth, he should have been left entirely alone in the world thereafter, and one wonders what became of the unnamed gentleman who had escorted him and paid his board. He could have been killed in the battle, of course, but it is perhaps more likely that he was only one of several of the late King’s followers charged with the task of escorting Richard from the area before any harm could come to him. We may assume that their instructions were to take him to a place of safety before shifting for themselves (whether by soliciting pardons or fomenting conspiracies against the new government), and that they would have entrusted his longer-term future to someone who enjoyed their confidence and who could receive a young stranger without arousing suspicion. Richard may not have told Sir Thomas Moyle everything, of course, and perhaps said he had gone to London (where he would have been almost as anonymous as a modern Londoner), to avoid explaining where, and with whom, he had been living for many of the intervening years.

Dr Warren, the recipient of Brett’s letter, gave it with the latter’s permission to Francis Peck, the antiquary, who published it in the second volume of his Desiderata Curiosa in 1779. Peck also refers to ‘another account’ of Richard’s story that had come to his notice, and gives in the first person what he says are ‘the most material differences’ between this and Brett’s narrative. Unfortunately some of his interpolations – for example, that the man who wore the star and garter ‘felt my limbs and joints’ and that Sir Thomas Moyle was able to inspect Richard’s book while he was asleep – do not add much to what we know already, and all of them must be treated with caution. The statement that ‘I was brought up at my nurse’s house (whom I took for my mother) ’till I was seven years old . . . then a gentleman, whom I did not know, took me from thence, and carried me to a private school in Leicestershire’ has probably been borrowed from the Parallel, and there is no reason to suppose the anonymous author had real evidence to support his assertion that King Richard chose not to reveal his identity (and did not tell the boy that he was his father) at their second meeting before Bosworth.

He [the King] asked me, whether we heard any news at our school? I said, the news was, that the Earl of Richmond was landed, & marched against K. Richard. He said, he was on the king’s side, & a friend to Richard … & said, if K. Richard gets the better in the contest, you may then come to court, & you shall be provided for. But if he is worsted or killed, take this money, and go to London, & provide for yourself as well as you can.

Richard did not know how to reach London, but in this version of the story was told first to make his way to Leicester, where, he says:

I saw a dead body brought to town upon an horse. And, upon looking stedfastly upon it, I found it to be my father. I then went forward to town [London]. And (my genius leading me to architecture) as I was looking on a fine house which was building there, one of the workmen employed me about something, &, finding me very handy, took me to his house, & taught me the trade, which now occupies me.13

It would appear that he had by now put two and two together and realised that he was the King’s son, but the whole scenario lacks conviction. He would surely not have risked mingling with the Tudor army in Leicester when he had been urged to escape as quickly as possible, and there is the same (improbable) assumption that his future was left to chance rather than entrusted to one or more of his father’s adherents. No writer explains why, if he found himself alone and friendless, he did not simply travel the few miles to Lutterworth and the safety of his old school and teacher, or why he did not take both himself and his new wealth to the court of his ‘aunt’, Duchess Margaret, in Burgundy. We are informed that his father gave him ten pieces of gold ‘viz. crown-gold, which was the current money then, and worth ten shillings apiece’ at their first meeting in the great house, and the large sum of 1,200 such pieces before Bosworth. This (£600) would not have disgraced the annual income of a minor baron, but there is no mention of where Richard kept it, or how much he spent before he began to earn his keep.

Richard’s name has been associated with a number of buildings and structures that stand, or used to stand, in the park at Eastwell, and the Earl of Winchilsea told Dr Brett that he remembered seeing a small dwelling called Plantagenet’s Cottage in his youth. It had been demolished by his father, the third earl (much to his disgust, apparently, since he told Brett that ‘I would as soon have pulled down this house’ (the new manor); but he did not doubt that it was the one-roomed lodge that the old man had built with Sir Thomas Moyle’s permission and that it confirmed at least this part of his story. A house in the park is still known as Plantagenet’s Cottage, and had a castellated pseudo-Gothic façade when Charles Igglesden noticed it in the course of preparing the third volume of his A Saunter through Kent with Pen and Pencil, published in 1901. Igglesden says that it is

no doubt very ancient, for its walls, which are of burnt earth and ballast, are about eighteen inches thick. The windows are of the shape peculiar to all the cottages on the estate, and the front door inside the massive porch is of oak between two and three inches thick, coffer-panelled and studded with largeheaded nails. The porch is very remarkable, being built of solid brickwork and carried up high above the roof. In the summer time it is covered with Virginia creeper, but with the falling leaf a dummy window is visible. There is an almost square cellar beneath one of the rooms, and this is credited with having been the hiding place of Plantagenet in times of necessity.14

The property has been remodelled since Igglesden’s time, and looks very different today.

The cottage may stand on the site of Richard’s original construction, but Igglesden also mentions a curious building known as Little Jack’s House, which he says used to stand near the reservoir.

The house now called ‘Plantagenet’s Cottage’. Pen and ink drawing on a postcard by Saxon Barton (founder, Richard III Society).

It was a brick building of two rooms, one on top of the other. Each contained a fireplace, but nothing is known for what purpose it was used beyond the statement that it was utilised for the isolation of a horse suffering from glanders. Until it became too ruinous for use buck beans were stored in it. There is a local tradition that the Plantagenet outcast hid there, but no conclusive evidence can be gleaned.15

The idea that Richard felt threatened during his time at Eastwell and sometimes had occasion to conceal himself is probably no more that later, largely idle, speculation, and the same may be true of two other features associated with him, what is still called ‘Plantagenet’s well’ and his supposed monument, which stands in the ruins of the church. The well lies ‘within a stone’s throw’ of the cottage, says Igglesden, ‘near the gas works on the Boughton road’.

It is between twenty and thirty feet deep and for a long time was a receptacle for all kinds of rubbish. It was an object of interest until about six years ago [i.e. the mid-1890s] when it was filled up with building refuse and thereby closed. A railing now cuts off that part of the park, but two fine trees standing close together mark the historic spot.16

The well is now bricked round for safety, but it is still possible to visit the much-damaged tomb and to visualise it as Igglesden saw it at about the turn of the nineteenth century.

Against the north wall, within the communion rails, is an ancient monument of Bethersden marble, which, tradition says, denotes the burial place of Sir Richard Plantagenet. The fact that the tomb originally had two brasses and a supplicatory prayer such as ‘Jesu, Mercy’, or ‘Mary, Help’, repeated four times on scrolls at the corners, leads archaeologists of the present day to confidently declare that the tomb is not that of Plantagenet, while additional doubt is cast on the tradition by the surmise that Sir Thomas Moyle, who held high State offices, including that of Speaker in the House of Commons, would not risk incurring Royal displeasure by erecting such a monument to the son of a king whose identity he had helped to hide.17

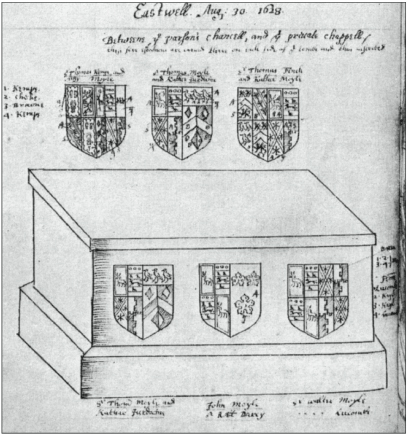

This view is confirmed by R.H. D’Elboux, who saw the tomb in, or shortly before, 1946 and described it as follows.

Half under a recessed arch in the north wall of the chancel is an altar tomb of Bethersden marble, the slab of which, though very worn, still retains traces of the indents for brasses. It measures 23 by 53 inches, and has a projection from the wall of 10¼ inches, with a chamfer edge of 2¼ inches on three sides, once containing a brass inscription an inch wide. The sides of the tomb are plain surfaced.

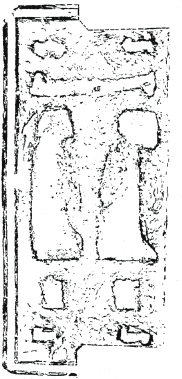

Sketch of ‘Richard Plantagenet’s tomb’, c. 1946, showing traces of indents for brasses (from Archaeologia Cantiana, 59 (1946)).

On the slab there have been four brass scrolls, one at each corner, and then one long lateral one immediately above the figures. The sinister figure was certainly that of a female of c. 1480–90, with the late type of butterfly headdress and probably wearing a mantle; the dexter is the most worn of the indents, and at first glance seems also to represent a female, but is more likely a male with long hair in civilian or judicial garb. The sinister longitudinal edge of this figure’s indent is completely obliterated. Both figures faced to the dexter, towards the altar. Below the dexter figure was a group of sons, seemingly two, and below the female a larger group of daughters.18

The figures cannot be identified with certainty but most probably represent Sir Walter Moyle, his wife Margaret, daughter and co-heiress of John Luccomb of Stevenstone, Devon, and their children. Moyle was a lawyer who was regularly summoned to Parliament and who served Edward IV as a member of various commissions and inquiries relating principally to the southern and western counties. He acted as judge of the Common bench at Queen Elizabeth Woodville’s coronation on 26 May 1465 and was then knighted, but his age (he was born in 1405) may have allowed him to avoid direct, personal involvement in the Wars of the Roses. He died in or about 1480, having fathered two sons, John (Sir Thomas’s father) and Richard, and possibly three daughters which would agree with the numbers apparently represented on the grave slab. He is certainly a more likely candidate than Richard Plantagenet, who, as far as we know, was unmarried and childless, and who did not arrive in Eastwell until more than sixty years after Sir Walter’s death.19

Exposure to the elements continues to erode what remains of the structure, which is now further threatened by several sturdy young saplings growing near to its base. Ivy and moss have all but obscured any remaining traces of the indents, and even the modern plaque bearing the legend ‘Reputed to be the Tomb of Richard Plantagenet 22 December 1550’ is barely legible. The tradition did not, presumably, exist in the early eighteenth century, or the Earl of Winchilsea and Dr Brett would surely have mentioned it. Indeed, Brett actually remarks that ‘we cannot say whether he was buried in the church or churchyard; nor is there now any other memorial of him, except the tradition in the family, & some little marks of the place where his house stood’.20 It was probably first said to have been Richard’s grave in the later eighteenth century, ‘though always, by writers of discrimination, with a reservation that the monument seemed of earlier date’.21

This then, is all we know of Richard of Eastwell. What of his ‘contemporary’, Prince Richard of York?