Nikolai was posing for a photograph with two low-ranking Turkish officers when the earthquake hit the ancient, ruined city of Ephesus. The photographer had just replaced the lens cap when they all felt the ground rise beneath them. They all lost their balance and staggered sideways, each one reaching out in an attempt to steady himself with whatever he could find. Nikolai managed to stay on his feet by leaning back against the wall of stone blocks in front of which they had been standing. The two Turkish officers ended up sprawled on the ground at his feet. While the ground continued to move in a disconcerting way he reached a hand out to each of them.

“Are you all right?” he asked in perfect French. The men grabbed his outstretched hands and managed to pull themselves upright.

“Yes, thank-you,” they replied in rather heavily accented French. Inwardly they were both cursing their stumbles – an earthquake notwithstanding – in front of someone they believed to be a well-to-do Belgian industrialist, who went by the name of André Gibaut. According to what he had told them he was in their country looking for a suitable source of certain raw materials for his factories back home. However, had the two Turks known they were being helped to their feet by a young officer in the Russian army, whose real name was actually Nikolai Alexandrovich Kostenko, they would have arrested him on the spot, taken him back to their barracks in the nearby valley, mistreated him appropriately, and then personally pulled the trigger at his execution once he had been cursorily tried before their commanding officer.

Nikolai was well aware of this possibility. As the earthquake continued, bizarrely his mind started going over the reasons why these solid, Turkish soldiers would treat him in such a way. The simplest reason was that Turkey and Russia were enemies, most recently fighting the Russo-Turkish War only eight years previously. A more complex and multi-faceted reason was that Russia had only the week before successfully taken the tiny oasis-village of Pandjeh in far-off Afghanistan, thereby almost certainly precipitating a major war with Britain, and Britain was looking to Turkey as an ally in its plans to attack Russia through the Caucasus. It was all rather tense, apparently. He had heard reports that the British newspapers were demanding that the Russians be taught a lesson they would never forget. On the other side, during one of those rare moments when he had been able to communicate safely with someone from Russia, he had learned that the papers in St. Petersburg and Moscow were insisting that their government continue pushing southwards through Afghanistan – thereby bringing the ultimate goal, India, ever closer – and warning Britain to keep well out of it.

In this intensely volatile situation Nikolai had been instructed by his superiors to enter Turkey posing as a Belgian and somehow to try and slow up Turkey’s alliance with Britain. He knew he was not alone in this task, that other Russians were present elsewhere in the country, but still he had struggled to find a way into the upper echelons of the Turkish army. By frequenting some very seedy bars and buying occasionally generous rounds of barely drinkable local wines he had managed to befriend these two low-ranking officers. But he had not yet been able to persuade them to introduce him to their commander, a man he had previously targeted as one who could be used to bring about suitable delays. Instead, they had promised to show him the ancient ruins of Ephesus and had brought him out to this grassy hillside with blocks of marble everywhere, statues lying broken in pieces on the ground or buried with only their heads peeking out from the soil, and very occasionally an intact wall. It was definitely the ruin of what must have been a very beautiful city, but it had clearly suffered the indignity of neglect as well as the occasional earthquake like the one currently reducing what still remained standing to little more than disordered piles of rubble.

Ah yes, the earthquake! Nikolai’s thoughts returned to the moment with a jolt as he became aware that the large blocks of stone making up the wall he was leaning on were beginning to separate in a way that did not bode well for the continued existence of the wall as a whole. Either it had been built into the side of the hill or the hill had at some time afterwards risen in an attempt to engulf it. Whatever the cause, having turned to face the wall, Nikolai could see small amounts of dirt falling out of the wall, as the cracks between the blocks widened.

“Quick, out of the way!” he called out, pushing the two Turks away. They skittered across the trembling flagstones and out into what they had grandly referred to as the Street of Curetes, one of the central roads of the ruins of Ephesus, but which looked like not much more than a goat track with occasional flagstones peeping through the dirt and grass. But Nikolai, turning to follow them, was suddenly struck by an enormous tremor that left him flat on his back looking up at the wall, helpless, as a large crack opened up between two blocks of stone. Incredibly quickly, the crack widened showering dirt and gravel over his feet. With a desperate scrabble he pulled his feet out of the way as a number of large stone blocks were seemingly levered out of the wall by the earthquake and landed with ear-splitting cracks on the flagstones around him.

And then it was all over. The ground stopped moving, the dust began to settle, and the two Turks had run over to see if he was injured.

“I’m fine,” he said, shrugging off their assistance. As Nikolai stood up one of the Turks went back to the photographer to see how he had fared while the other stayed with Nikolai. Out of interest, Nikolai looked back at the wall. He had been partly right: the wall had been built into the side of the hill, so where the blocks had been he could see dirt and rocks. But near the bottom of the wall, behind what would have been the second level of blocks, he noticed an opening, little more than a hole in the side of the hill.

“What’s that?” he said, pointing.

The Turk nearest at hand had also noticed the hole and together they went over to it. Nikolai looked in but his head blocked out most of the sunlight.

“Sir, do you see anything?” asked the Turk.

“No, this hole is too small,” he replied.

He worked at the edges of the hole to make it a little wider. He felt quite excited about doing this. Since Ephesus was such an ancient city perhaps he might find something valuable. Some coins, perhaps? Gold even? With a larger hole and a little more light he could now see that the hole opened into a hollowed-out space that had been hidden behind the wall. He could also see that taking up most of the space was a stone box about a foot and a half in length and a foot wide and high.

“There’s something here.”

The Turk caught the edge of excitement in Nikolai’s voice. “What is it? Can you reach it?”

“I think so.”

With great care he took hold of the box and slowly drew it out of the hole. In the clear light of day it looked very old yet was still intact. Underneath some chips and scratches Nikolai could see some rather beautiful carved decorations. The box also had a lid that was slightly cracked but not broken.

“Oh, sir!” exclaimed the Turk, with a wild look in his eyes. “Put it back: it’s an ossuary.”

The man had used a word that Nikolai was unfamiliar with. “A what?” he asked, carefully turning the box around with his hands.

“It’s an ossuary,” the Turk repeated. “It contains the bones of someone great.”

“Who?” asked Nikolai in surprise.

“I do not know,” said the Turk. “But it is extremely unlucky to meddle with the dead.”

It occurred to Nikolai that this Turk may be wanting him to put the box back just so he could return – once Nikolai had gone – and take the box for himself. However, Nikolai felt that this treasure of antiquity was his, not only by right of seniority, but mostly for the fact that it was his feet that had narrowly escaped being crushed by the blocks of stone that had been guarding this box for who knew how long. And he had pulled the box out of the hole in the first place. He was not going to lose possession so easily. Instead, he exclaimed, “Let me see inside!”

“No!” cried the Turk, wringing his hands in a decidedly believable display of either sheer terror or thwarted avarice.

Nikolai took no notice. He placed the box on the floor and tried to remove the lid. It was tightly wedged on but he felt it move slightly, then suddenly it was off. However, much to his disappointment the box did not contain bones, or articles of gold and precious stones, not even a few measly coins. Instead, it seemed full of paper. He reached in and poked the rough paper with his finger to see if there might be anything wrapped up inside.

The Turk seemed to have brightened up considerably. Whether this was from his relief at finding that the box was not after all an ossuary and that his soul was now safe from any ancient curse, or his relief that there was nothing of value inside, Nikolai did not wish to decide. However, Nikolai had taken a fancy to the box itself with its intricate carvings. So he made up his mind to take it as a souvenir of his visit to Ephesus.

“I hope you don’t mind if I keep this box,” he said, replacing the lid and then tucking the box firmly under one arm.

“Not at all, sir,” replied the Turk, magnanimously. “Since it is not an ossuary, you have nothing to fear from the dead.”

Indeed, thought Nikolai. And since it is not valuable, I have nothing to fear from the living either.

The photographer and his apparatus had apparently survived the earthquake, although he had discovered that the lens cap had come off thereby exposing to the sunlight the plate that he had taken earlier. He loaded another plate and the Turks moved in on either side of Nikolai, his arm still around the box. Once again, they looked serious and the photographer removed and then quickly replaced the lens cap.

As they walked back to the nearby town Nikolai thought that, all in all, it had turned out to be quite an interesting day, certainly one worth writing up in his diary…

While on holidays in Nizhny Novgorod, Natasha found Nikolai’s diary when, after finishing the only book she had brought with her, she went scouring through some bookshelves looking for something else to read. She and her husband Dima – short for Dmitriy – had travelled down from St. Petersburg to spend a couple of weeks with Dima’s grandmother, in the city of Dima’s birth, an event which had occurred some thirty years previously. Natasha, a few years younger, had met Dima when he had moved to St. Petersburg to study graphic design. They were both good-looking with typical Slavic features: dark hair and fair complexions, with well-defined cheekbones.

The diary itself had looked quite interesting, being bound in leather with filigree patterns of gold on the spine but no title. She had pulled it out to see what the book was, but there had been no title anywhere on the cover either. So she opened it to the first page and was surprised to see that it was all in handwriting. Then, when she looked closer, she realised it was in French. Having studied French at both school and university, and rather intrigued, she returned to her seat in the main room of the apartment and read the first page:

Wednesday, 14th January, 1885.

I arrived in the land of the Ottomans with a minimum of attention. The ship docked early and my colleague was not there to meet me. After finalising my affairs with the First Mate and collecting my travelling bag from my cabin I strolled down the gangplank to where my large trunk was waiting for me. I was able to procure the assistance of some lively local lads to help transport my trunk to a suitable place of temporary residence in which I write these few words. I expect my colleague to arrive presently and so I shall know my itinerary shortly.

Natasha found it slow going. For a start, the handwriting was difficult to read. The writer had used long flowing cursive, and it had faded a little over time. In addition to this, the French was somewhat archaic, and there were quite a few words of which Natasha was a little unsure of their meaning. However, she kept at it and began to form a mental picture of the writer. Apparently, he was a Belgian industrialist who had travelled to Turkey for some reason that was never explicitly stated in the diary. He had moved around for a few months, mostly under the watchful eye of various Turkish officials. Natasha had just finished reading some of the writer’s thoughts on the many Turkish factories he had been given tours through when Dima returned from shopping with his grandmother, Nadezhda.

“We’re home!” called Dima from the small entryway of the apartment.

Natasha put the diary down and went and helped them with the bags as they removed their street shoes and put on some slippers. Then, as they unpacked and Nadezhda placed items away in their correct locations, she asked Nadezhda about her discovery.

“Grandmother, I found someone’s diary on your bookshelves. It’s in French. Do you know whose it is?”

Nadezhda paused, the packet of pasta in her hands forgotten for a moment.

“Yes, my child. I know it. It was written by my grandfather.”

“Really?” exclaimed Dima. “I didn’t know you had French blood in you!”

“Oh, he wasn’t French,” Nadezhda replied with a chuckle. “Nikolai Alexandrovich was as Russian as they come. He was an officer in the Russian army for many years, you know.”

“Yes, I vaguely remember you mentioning him before,” said Dima.

“But why was he writing in French?” asked Natasha, with a perplexed frown on her face.

“I seem to recall he was pretending to be Belgian at the time. After all, Turkey was not a very safe place for Russians back then, especially officers in the Russian army.”

“Oh, he was spying!” said Natasha excitedly, clapping her hands together. “How thrilling! I’m going to read some more.” She left the tiny kitchen and returned to her seat in the other room.

“Read it to me,” said Dima, following her. “I don’t know French.”

“Certainly,” she replied.

So with Nadezhda listening from the kitchen, Natasha read the next entry out loud, translating into Russian as she went.

“ ‘Friday, 24th April, 1885.

“ ‘I have befriended two young Turkish officers, Ahmed and Mustafa. They are both great connoisseurs of red wines, despite all Islamic prohibitions to the contrary. We have had many interesting discussions, whilst enjoying the subtle flavours of a worthy local vintage, concerning the politics of army life, especially the shame of being passed over for promotion. I have assured them both of their inestimable qualities and can guarantee great things for them if only they would speak to their commanding officer about doing business with a certain Belgian industrialist of their acquaintance. Perhaps as a result of too many refills of the truly excellent local vintage, I had to explain that I was referring to myself. I am hopeful that this tactic will bear fruit before too long.’ ”

Natasha turned the page, and a folded piece of thick paper fell out onto her lap.

“Oh, what’s this?” She put the diary down on the nearby table and picked up the paper. She opened it up to reveal a very old photograph of three men standing in front of a stone wall. The two men on either side of the central figure were clearly Turkish soldiers. The man in the middle was tall, elegantly dressed, with quite a long moustache. He was also carrying what looked like a stone box under one arm.

Upon hearing Natasha’s exclamation, Nadezhda had come into the room. Looking over Natasha’s shoulder, she said, “Yes, that’s my grandfather. That’s Nikolai.”

“He’s rather handsome,” said Natasha. “I can see where Dima gets his good looks from.”

“Oh, yes, he was the handsome one,” replied Nadezhda. “He came home from his army days with a bad leg that always gave him grief in the cold. But he had his pick of the girls of the town. I always thought he and Babushka made such a beautiful couple.”

Dima, a little bemused hearing his grandmother talking about her own grandparents, said, “Keep going, Natasha. I want to hear what happened next.”

“OK.

“ ‘Monday, 27th April, 1885.

“ ‘What an amazing day! I have lived through an earthquake and have made an interesting find as a result. I went on an excursion with Ahmed and Mustafa to see the ruins of Ephesus. It is the done thing, apparently. If one is in the area, they told me, it is essential that one visit the ruins. They even took a photographer along to capture the moment forever.

“ ‘We had walked up to the top of the hill and then meandered our way down a pathway that Ahmed referred to as the Street of Curetes. Personally, there was not a lot to see. However, further down the hill there are some passably intact ruins and some intriguing statuary.

“ ‘We were posing for the photograph in front of a fairly unprepossessing stone wall opposite what remains of a building Mustafa optimistically referred to as Trajan’s Temple when the earthquake struck. My companions all fell over, but I kept my feet until the wall behind me started to collapse. I bravely pushed the others out of the way and barely avoided being flattened by the blocks that fell from the wall. However, once the earthquake ceased I noticed a hole in the wall. Inside this hole I found a stone box, beautifully carved. I have kept it as a reminder of my visit to Ephesus and of my narrow escape from serious injury. From what I have seen it contains some papers – very old – with writing that I cannot read. Perhaps I will show them to someone when I get home.’ ”

“Let me see that photograph again,” asked Dima, suddenly.

Natasha handed him the photograph and Dima scrutinised it closely.

“Look,” he said, pointing, “you can see the hole in the wall, here behind this man. I wonder if that’s Ahmed or Mustafa? And that must be the stone box Nikolai’s holding.”

“Did he bring the box home, Babushka?” asked Natasha.

“I don’t know,” Nadezhda replied with a shrug. “I think there are a few bits and pieces of his at our dacha. But I never saw a stone box.”

“I’d love to have a look,” said Dima.

“So would I,” added Natasha.

They both looked at Nadezhda.

“Oh well,” she replied. “I guess we can go tomorrow. Victor will be there with his family, but we can all squeeze in. Now, put that book away and come help me make dinner. Then we can go to bed and get an early start.”

A man stood on the hill overlooking the small harbour of Patmos, gazing intently out to sea. Occasionally, he would cast a frustrated glance at the empty harbour below.

Three weeks and no ship!

If ever there was a moment that he resented his enforced stay on this tiny island off the coast of Asia[1], this was it. The vision that had been burned across his mind and that he had painstakingly translated into writing was one that the church back home so desperately needed. He knew that things were getting worse. The last report he had received had been a couple of months ago and it had told him of the martyrdom of Antipas, his beloved brother in Christos. Tears rose in his eyes as he recalled that fateful message.

And now, he had a message of his own and no ship to bear it away to Ephesus.

Wearily, he turned around to find something suitable to sit upon. Off to his left he spotted a rounded boulder. Moving over to it, he sat down and turned his attention back to the empty sea, scratching aimlessly at his thick black beard.

But the sea was no longer empty. There, on the horizon, a sail could be seen.

His weariness forgotten, the man jumped to his feet and set off down the goat path back to the town and the small empty harbour that was soon to be empty no longer.

Oh, thank-you, Lord, for bringing this ship, he prayed as he jogged down the path. I know that Your timing is perfect, even if I have felt this delay so keenly. Please, go with this message and quickly bring back Loukas, the one on whose shoulders so much will be borne. I pray that you will be strengthening him for the task even now. You know he will need it…

“Hey, Dima, look at this!”

The train had just pulled out of the main station in Nizhny Novgorod. Dima, Natasha and Nadezhda were on their way to the family’s dacha, a couple of stations away from the edge of the city. Natasha had been reading Nikolai’s diary but now she leant over to Dima, holding the book out for him to examine.

“Look,” she said. “Nikolai has reverted to Russian now.”

Sure enough, the entry that Natasha was pointing to was in Russian so that even Dima would have been able to read it.

“I wonder why?” he said.

“He explains it in the text,” Natasha replied. “Listen.

“ ‘Thursday, 25th June, 1885.

“ ‘I finally managed to get across the Turkish border into Russian-controlled territory, and have made it as far as Baku. Oh, it feels good to be able to speak (and write!) in Russian again, and not have to pretend to be that boorish Belgian industrialist. If I never have to speak French again, it will be too soon!

“ ‘My mission was reasonably successful. I may not have single-handedly prevented Turkey from joining Britain in a war against Mother Russia. But I feel that as a result of a few small incidents such a thing may be less likely in the foreseeable future. Be that as it may, as soon as I made contact with a superior officer, I was re-assigned to Bokhara and must immediately set sail across the Caspian Sea. I have been issued passage on the Prince Bariatinski – an aging paddle-steamer that has seen better days – and from there take the Transcaspian Railway as far as its continuing construction allows. All of this will be something to see, I have been told. Apparently, the only way to make a civilised crossing of the many deserts of Central Asia is by train. One certainly avoids a lot of messing about with camels and having to carry your own body weight in water.’ ”

Dima laughed. “I think I would have liked Nikolai.”

“Yes,” replied Nadezhda with a smile, “I think you would have.”

“I wonder what he meant by ‘a few small incidents’?” pondered Natasha.

“Best not to dig too deeply, my dear,” replied Nadezhda, the smile fading quickly. “It was a different world back then. People in military service often had to perform certain activities which we might be horrified by.”

“Like desecrating a significant archaeological site without even blinking?” exclaimed Dima.

“That wasn’t quite what I had in mind,” said Nadezhda, “but it’s a good example of the times. In some ways, it’s surprising there is anything at all left to see of these ancient ruined cities.”

“Which stop is it again, Babushka?” asked Dima, looking out the window of the train at a station, trying to catch a glimpse of a sign as they accelerated away.

“Ours is the next one. We should probably get ready to get off since the train will not stay motionless for very long.”

Indeed, when the train pulled into their station shortly afterwards there was barely time for the three of them to open the doors and step down onto the platform with their bags before the train blew its whistle and took off.

Uncle Victor was waiting for them. There was no telephone at the dacha – in fact, while they did have electricity, there was no running water and they cooked on a wood stove – but he had happened to ring from the bar in town the night before requesting that his mother, Nadezhda, bring a few items from her kitchen when she next made the trip out. She had told him of their plans to come the next day and so here he was to meet them. Uncle Victor was a big bear of a man, with huge arms stuffed full of hard muscle from years working in a timber yard. He gave Natasha and Dima each a spine-cracking hug that would have made a chiropractor cringe in horror, before grabbing their bags, one in each hand, and leading the way off the platform. Dima followed, carrying Nadezhda’s bag, with the others close behind.

They had to walk to their dacha. It was located approximately three kilometres from the station, so one did not want to make the journey too many times a day. There were a few shops – and the bar, of course – near the station, so they made a few necessary purchases and then began their walk. The dirt track took off straight as an arrow through a forested area that was riddled with dachas. On either side of the track, smaller, windier tracks took off through the forest leading to the rickety shacks and carefully cultivated vegetable gardens neatly surrounded by wooden fences, which made up each family’s dacha. Everywhere, Dima saw old friends of his family who had been working these plots of land for decades. Many stopped what they were doing to wave at Dima and Natasha who they had not seen for quite a few years. Dima knew that he would have to stop in when he next walked past and say a proper greeting to many of them.

Eventually, the main track dwindled down to the size of the side tracks and then it suddenly turned to the left. And there, on the right of the path stood their dacha. It was quite large with an upstairs consisting of a few bedrooms simply crammed with beds and chairs that fold out into beds. Downstairs, there were another couple of bedrooms, a living area, and a kitchen. There was an outhouse located at a suitably discrete distance from the main house and a wash room not too far away. There were also a number of ramshackle sheds in which Dima and Natasha were hoping to locate any remaining items of Nikolai’s.

It was quite late, despite the fact that it was still quite light outside. For these were the White Nights, that time of the year when the sun barely dips below the horizon resulting in nearly 24 hours of daylight for a few weeks. Uncle Victor’s wife Aunt Olga had cooked up a batch of borscht, so they all sat down to big bowlfuls of the soup – garnished with a little sour cream and dill – accompanied by chunks of bread. After the walk from the station it was quite satisfying, despite the incessant noise generated by Uncle Victor and Aunt Olga’s three young children as they fought over the remaining chunks of bread.

Dima and Natasha had been allocated a room upstairs so after the meal they excused themselves and went up to get their bed ready.

“I guess we can’t look for anything now, can we?” asked Dima, wistfully.

“No,” replied Natasha. “It will be better to start in the morning. We wouldn’t want to disturb anyone by making any noise.”

“True. Nikolai’s stuff, if it is still here, must be well and truly buried under more recent deposits.”

“Do you want to hear some more from the diary?”

“Sure.”

They changed into their night clothes, then climbed into bed. Natasha opened the diary to the next entry.

“ ‘Tuesday, 30th June, 1885.

“ ‘The Prince Bariatinski actually managed to get to Krasnovodsk, despite the best efforts of the captain and crew to sink her in the middle of the Caspian Sea. Granted the weather was foul, but that isn’t really an excuse for nearly capsizing a paddle-steamer, something I would have thought should be rather difficult to achieve in any circumstance. I am rather grateful that my trunk escaped any significant damage, especially since it contains my charming stone box. Anyway, we are here now and I am waiting to embark upon the Central Asian express!’ ”

“Excellent!” exclaimed Dima. “He still has the box!”

“Had,” replied Natasha. “At the time of writing, he still had the box. Whether he managed to get it back to Russia is another story. You do realise where he was heading, don’t you?”

“Well, of course. The Transcaspian Railway provided a backbone for all of Russia’s activities in the Central Asian region, most especially the carrying of troops from one point to another with amazing speed, putting down native rebellions here, extending their territory southwards there. In some ways I’m surprised we never did attempt an invasion on the British in India.”

“Yes, I don’t need the lecture, but I’m glad you know he was taking the stone box into what was essentially a war-zone.”

“Is that the end of the entry?” asked Dima.

“Yes,” replied Natasha. “That’s all for that day.”

“Perhaps,” said Dima with a yawn, “that should be all for our day, too. Good-night.”

“Good-night, Dima.”

As Natasha placed the diary down on the floor Dima reached over to turn off the reading light. Switching it off made little discernible difference to the ambient light in the room even with some curtains drawn across the windows. With a groan, Dima pulled the light blanket over his head in an attempt to block out the light.

It must have worked, for when he woke up and glanced at his watch Dima discovered that it was just past 7 o’clock the next morning. Natasha must have already got up so he got out of bed, quickly got dressed and headed downstairs for breakfast.

He found Natasha stirring some kasha on the wood stove. The porridge looked to be ready so he gave Natasha a good morning kiss then helped by getting out some bowls.

“Wanting an early start, were you?” asked Dima.

“Early?” laughed Natasha. “You’re the last one to get up! Aunt Olga has taken the children into town for groceries. Uncle Victor’s out in the garden working.”

Somewhat chastened, Dima ate his kasha quickly.

“Actually, I did want to get up early,” said Natasha. “I wanted to start looking for the box. I’ve gone over most of the house, already.”

“Find anything?” asked Dima, chasing the remaining dollop of kasha around his bowl with his spoon.

“Nothing so far,” she said. “But I’m expecting that if it’s here at all it will be in one of the sheds. Your grandmother said there was quite a lot of old junk in those sheds.”

“I was thinking about that last diary entry. I think we should probably look for Nikolai’s trunk.”

“Why? Because the box was in it when he was crossing the Caspian Sea? That doesn’t mean he left it there for good.”

“No, but it’s a distinct possibility. Anyway,” said Dima, getting up suddenly and giving his bowl a quick rinse using some water from the bucket next to the stove, “let’s get out there and have a look!”

Natasha followed him out of the kitchen and along the short passageway to the back door. Outside, it was already quite warm and very sunny. They greeted Uncle Victor who was digging in the garden, preparing to plant some radishes judging from the seed packets off to one side. The biggest shed was near the outhouse. Dima opened the door and stepped inside.

It was rather gloomy. There was dust everywhere, covering most of the tools lying on a long bench that took up one of the walls. You could quite easily deduce Uncle Victor’s most recent hobby simply by looking at which tools were mostly dust-free. Currently, it appeared that he was going through a wood-carving phase; all the chisels were clean.

Along the back wall various generations of Dima’s family had placed boxes of stuff they no longer had room for in their city apartments. As Dima and Natasha started looking in boxes they unearthed many strange and interesting objects. Dima found a box that contained some of his childhood toys. Forgetting about the search for Nikolai’s stone box for a few moments he idly flicked through the toys, remembering events from his past, many happy, a few that were sad.

Dima’s reverie was broken when Natasha exclaimed, “Hey, look at this!”

Thinking she had found the box, Dima dropped his childhood memories and rushed over to where Natasha was kneeling, peering into a large cardboard box.

“What is it?” he asked, somewhat breathlessly.

He looked into the box and was at first disappointed to see what looked like a few very old x-rays made of thick plastic. However, on closer inspection he could see what looked like concentric circles – or was it one long spiral? – etched into the surface of the x-rays.

“Do you know what these are?” asked Natasha, eagerly.

“Not really,” replied Dima.

“I think these could be illegally-distributed pop music records. During the sixties, the latest music was recorded off short-wave radio and then somehow transferred onto this thick x-ray plastic. Then you play them on a record player. If the KGB found you with one of these they would arrest you, since western pop music was considered highly subversive. This could be an old Beatles LP or something.”

“Goodness me! I wonder who the radical was in my family? It couldn’t have been my father. I don’t think he ever spoke about liking the Beatles. Perhaps Uncle Victor would know.”

Dima took the x-ray out to Uncle Victor while Natasha continued searching through the boxes. He came back shortly afterwards with a surprised expression on his face.

“Apparently they were my father’s after all. And, yes, they are the Beatles. Uncle Victor doesn’t think they would still play but he remembers sitting with my father while he played them to his friends. These must be worth a small fortune!”

He put them carefully to one side and continued searching.

Lunchtime came and went without them finding anything else of note, let alone the stone box of Nikolai’s diary. After lunch they moved to the other shed and quickly discovered that the roof of this shed had been much less waterproof than the other one. There were a number of wooden boxes full of papers that had been wet, then frozen, then thawed, then dried every year for some decades. Dima pulled out paper bricks more suitable for use as building material than for reading.

They were about to break for an afternoon coffee when Dima pushed aside the lid of a wooden crate to reveal a large box made of dark wood. It looked old and worn as if it had seen much of the world. If this was not Nikolai’s trunk then it was some other member of the family’s trunk from about the same period and certainly worth a look inside.

“This must be it,” said Dima.

Natasha had been taking a short breather, sitting on a pile of books. She quickly got up and came over to Dima.

“It certainly looks promising.”

Together, they pulled the trunk out into the middle of the cleared area of floor. The trunk was locked with an ancient and heavily rusted padlock. Dima ran to the other shed and returned with one of Uncle Victor’s chisels and a hammer. With a nervous look at Natasha, Dima took the chisel, positioned it over the arch of the padlock, and then gave it a heavy blow with the hammer. The padlock practically disintegrated before them.

“Careful!” exclaimed Natasha.

“It’s all right,” said Dima, placing the hammer and chisel on the ground. “Help me with the lid.”

The lid must have seized many years previously. Even with Natasha’s help it would not budge. Eventually, Dima took the hammer and chisel again and carefully used them to pry apart the lid from the rest of the trunk. When the lid came open with a nasty creak the contents of the trunk were finally on display.

Dima was pleased to see that everything in the trunk looked to be in surprisingly good condition. There were articles of clothing that were not the least bit affected by insects; there were books that could be opened; there were papers that were dry and readable; there were a couple of knives that still looked sharp enough to cut through sizable logs with little physical exertion. And there at the bottom of the trunk, underneath an old army coat, was a stone box looking exactly like the one in the photograph of Nikolai taken at Ephesus.

“There it is,” whispered Natasha in awe.

“We found it,” said Dima, solemnly.

“Let’s take it inside.”

“OK.”

Dima picked the stone box up, carefully lifting it out of the trunk. Then he went outside and made his way over to the house followed closely by Natasha. They quickly went up to their room, shut the door, and Dima placed the stone box carefully on their bed. He looked up at Natasha and gave her a nervous grin.

“Here goes.”

Slowly, he removed the lid of the box. Immediately they could see that the box was not empty; there was something made of paper, or possibly something wrapped in paper, taking up almost the entire box. He put the lid down carefully on the bed beside him. Then he gently prodded the paper. It was quite coarse in construction, a light orange in colour. It showed no immediate signs of disintegrating. Nevertheless, Dima did not want to pick it up yet.

“What is it?” Natasha asked.

“I’m not sure,” he replied.

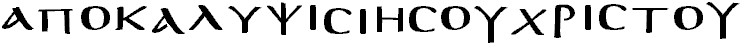

He bent a little closer. Actually, upon closer inspection it looked to be a roll of paper with the leading edge visible on top. He gently lifted up the edge by the right corner and saw that there were letters on the underside. Greek letters.

“Natasha, can you turn on the reading light?”

She got up switched on the lamp, positioning it so that the light fell onto the inside of the box. Dima looked again at the first line of letters that were visible. They were all hand-written capital letters and there were no spaces:

“Can you read it?” Natasha asked.

“Well, I’m not sure where the word breaks are, if there are any, that is.”

“Try reading it aloud.”

“OK.”

Dima paused.

“I’m guessing the first letter is an ‘A’,” he said, uncertainly. “Then the next three are just like Cyrillic, so the message starts, ‘A-PO-KA’…”

He paused again.

“I’m not sure about the next one,” he continued, eventually. “It could be an ‘L’. I mean, it’s fairly similar to a Cyrillic ‘L’. Then comes a ‘U’, just like the Cyrillic.”

Again, Dima paused. The next symbol had him stumped. It was nothing like a letter from either the Cyrillic or the English alphabets.

“What’s wrong?” asked Natasha.

“I’m stuck,” Dima replied. “I don’t know this next one.”

“Well, what have you got so far?”

“ ‘APOKALU’,” he stated, and suddenly he had it. “I know! The next one is a PSI. I remember it coming up in a Physics formula back in high school. So that makes it ‘APOKALUPS’.”

Natasha’s eyes widened.

“Apocalypse?” she asked, wonderingly.

“Maybe,” replied Dima.

“What’s next?”

“Well, the next letters are ‘ISI’ assuming that they are all like the Cyrillic. Then the next one could be an ‘N’ if it’s like the Cyrillic, or ‘H’ if it’s like the English, but I don’t know which is right.”

“Try them out,” suggested Natasha.

“OK,” replied Dima. “ ‘APOKALUPS ISIN’? Maybe. ‘APOKALUPS ISIH’? Not very easy to say. So let’s stick with ‘N’. Then comes ‘S’, ‘O’, ‘U’, ‘CH’…” (Dima pronounced this sound as it appears in the German name ‘Bach’ or in the Scottish word ‘loch’) “…‘R’, ‘I’, ‘S’, ‘T’, ‘O’ and ‘U’ – all just like the Cyrillic.”

“Can you see any more?” asked Natasha.

“No, not without opening the roll up further.”

“So what does is say?”

“ ‘APOKALUPS ISIN SOUCHRISTOU’.”

“The last part sounds like ‘Christ’,” said Natasha.

“ ‘APOKALUPS ISINSOU CHRISTOU’,” repeated Dima.

They sat there quietly for a few moments. “Are you sure about that ‘N’?” asked Natasha, finally.

“Not really,” replied Dima.

“Because,” continued Natasha, “if you said ‘I-AY-SOU’, then you would have something that sounds very much like ‘Jesus Christ’.”[2]

“And then the whole thing would be ‘APOKALUPSIS I-AYSOU CHRISTOU…’ ” said Dima, excitedly.

“And that sounds a lot like ‘apocalypse Jesus Christ’,” said Natasha.

“It does,” said Dima, with a slight shake of his head as if he did not quite believe it. “I didn’t know Jesus Christ wrote an apocalypse.”

“What about the book of Revelation?”

“Well, that’s possible,” replied Dima, uncertainly. “But if you’re right, that would make this what looks to be a very old copy of Revelation.”

“Oy!” exclaimed Natasha, using a Russian exclamation similar to the English ‘Oh!’ but usually said with much more feeling.

“Yes,” agreed Dima, “oy!”

A young man stood near the prow of a small cargo ship as it forged its way through the choppy waves of the Aegean Sea. The wind tousled his dark hair, forcing it over his eyes, apparently trying to prevent him from staring at the coastline of a small island in the distance.

“Is that it?” he asked one of the deckhands who happened to be passing at that moment fiddling with a rope.

“Aye, that’s Patmos.”

Loukas smiled to himself. He had been travelling now for just short of a week and he was pleased to be nearing the end of the voyage. In fact, he was excited, but not because he was sick of the constant rolling of the sea that made it difficult to walk around and keep down the meagre provisions that comprised a sailor’s diet. He was excited because he would very soon be in the presence of Ioanneis once again.

Ioanneis! Just the name was enough to send shivers of anticipation down Loukas’ spine. The man had been one of the many Christian refugees fleeing from the horrific Jewish War that had left Jerusalem in ruins. He had quickly become a leader in the church of Ephesus. After all, he had been converted by one of the very Apostles themselves! He always used to say that the gospel written down by Markos was his favourite: it reminded him of the forthright and colourful way that Petros spoke. That’s right, he actually knew Petros! At least, before Petros went to the church in Rome, soon after to be beheaded by the emperor… Neron. Loukas could barely bring himself even to think that beastly name.

Ten years ago Ioanneis had baptised Loukas into the Way. But then just last year Ioanneis had fallen foul of the local authorities. Apparently, some of the residents of Ephesus had objected to comments he had made about eating food that had been first offered to the goddess Artemis. Ioanneis had been teaching in the church that Christians should not eat such meat for it had been associated with demons. Some of the followers of Artemis had heard about this and had become enraged. They had laid in wait for him one dark night as he had come out of the Agora, followed him as he headed to his house, and then jumped him. That probably would have been the end of it had not a Roman patrol been within earshot. They had heard his cries for help and come running. However, applying the principle of mob rule they immediately arrested Ioanneis. After all, following the logic of the situation, if a mob wanted him dead then he must have done something wrong.[3]

Ioanneis then appeared before the public tribunal and had promptly been found guilty of treason against the State. This new charge had been necessary since treason against Artemis was not in itself something the authorities could punish. Of course, everyone knew he was not guilty of treason against the State, even the members of the tribunal themselves, and this was reflected in his sentence. People found guilty of treason were usually beheaded if they were a Roman citizen; if they were not a Roman citizen they were crucified. Since Ioanneis was a Roman citizen from a well-respected and, more importantly, wealthy family instead of losing his head he lost his freedom: he was sent into exile to the penal colony on the island of Patmos.

This had happened over a year ago. Since that time word had come from Ioanneis occasionally. Essentially, when a ship that had recently travelled from Patmos came into the harbour of Ephesus someone from the church would ask the sailors about him. Usually, one would have a verbal message or occasionally even a written letter. Similarly, the churches of Asia had sent letters back, informing him of recent events such as who the authorities had imprisoned and how the church was coping with this and other forms of persecution. In this manner he had continued to have a leadership role in the church even from a distance.

Then, a week ago, the church had received a brief and rather enigmatic letter:

From Ioanneis a servant of God on Patmos for the sake of the word of God,

To the church in Ephesus.

Grace to you and peace from our God and Father and from the Lord Iēsus[4].

I have something important to say to you and to all the churches of Asia. Send Loukas son of Theseus and I will prepare him for what is to come. Be encouraged! The Lord knows you and your deeds.

The brothers here with me send their greetings.

Everyone had been quite excited to hear what he had to say, although they had wondered why he had not just said it right then and there in the letter. And the line ‘The Lord knows you and your deeds’ had given some of the more mature members of the congregation pause for thought for it could be taken either positively or negatively.

So the church had prayed for Loukas and within a few days he was on a ship bound for Patmos. They had hugged the coast until they had reached Miletus where they had stayed for a couple of days, and then they had headed westward – island-hopping so as not to get lost – until Patmos came into view. Now, he watched the island get bigger and bigger as they sailed closer, but it was not until they rounded the peninsular and the small harbour of Patmos lay before them that he uttered a brief prayer of thanks for his safe arrival.

There was no one waiting for him when the deck hands leapt over the side to tie the boat to the small, wooden dock. This was not surprising since Ioanneis would have had no way of knowing when he was arriving. However, he had no idea where to go. He picked up the small cloth bag that contained his few travelling possessions and clambered onto the dock himself.

The island of Patmos was a penal colony. But it was not one enormous prison. Certainly, there was a prison camp on the island where criminals were sent deportio ad insulam, that is deported by the Emperor himself and confined to a prison where they would serve out a life sentence of hard labour. But there were also people here relegatio in insulam, that is, those who had been relegated by the provincial governor to the island but who then had considerable freedom of movement within the island context. They could earn a living and even own property. As a result a small town had sprung up to service the Roman garrison and those who had been forced to make Patmos their home for the rest of their lives. Despite its relative isolation, there had been a few entrepreneurial types willing to move to Patmos in order to make a living providing goods and services to the often wealthy men and women who had fallen foul of the Roman government for whatever reason.

From the messages and letters the church in Ephesus had received from Ioanneis, he had apparently adapted quickly to his new setting. He had immediately started speaking to his fellow ‘relegatees’ about Iēsus and had quickly made a few converts. Their regular meeting together had formed the seed of a growing church. Before long they were visiting the more serious criminals in the prison and had even made some converts amongst the Roman soldiers doing their tour of duty maintaining order in the small colony.

Loukas made his way from the dock into the township. It was late in the day and there were only few people about. The light was draining quickly from the sky and darkening clouds to the north promised stormy weather in the near future. In need of directions, Loukas caught the attention of a man sitting near a grain store mending some clothing in the fading light.

“Excuse me, sir, I’m looking for Ioanneis of Ephesus.”

“Ah, yes, I know the man. A relegatio, yes?”

“That’s right. Do you know where I might find him?”

“Certainly. Follow this road up the hill until you come to the statue of our lord and god Emperor Domitianus. Turn left and when you come to the gymnasium the house you are seeking will be on the right.”

“Thank-you.”

Loukas took his leave and followed the man’s directions. As he passed the statue of Domitianus he shuddered slightly, refusing to make the required sign of obeisance, but no one was present to see this tiny act of treason. He quickly located the gymnasium and was pleased to see light emanating from the house next to it. He knocked at the door.

It was opened by a large, broad-shouldered man with a full, black beard. His friendly eyes were surrounded by laugh-lines that crinkled when he smiled. He was smiling now.

“Loukas, son of Theseus, come in, come in!” he boomed.

“Ioanneis. It’s good to see you again.”

Ioanneis grabbed him around the shoulders with one arm, and, taking Loukas’ bag with his other hand, ushered him into the house. Inside, there were five or six men and women sitting on the floor. There were a few lamps burning and a large scroll lay open on the floor.

“Loukas, you come near the end of our meeting. We have been reading from the prophet Isaiah.” He indicated a place for Loukas to sit, then sat himself. “Daria, please continue.”

A woman wearing a brightly coloured shawl over her head was sitting closest to the scroll. Hesitantly, she began to read.

“ ‘Behold, I will create new heavens and a new earth. The former things will not be remembered, nor will they come to mind. But be glad and rejoice forever in what I will create, for I will create Jerusalem to be a delight and its people a joy. I will rejoice over Jerusalem and take delight in my people; the sound of weeping and of crying will be heard in it no more.’[5]”

She stopped, and after a brief silence Ioanneis spoke softly.

“This is how the story ends, my friends. Through all the pain and suffering that you have already experienced and all that is yet to come remember this: it will be forgotten entirely when we are living in the joy of God’s New Jerusalem.”

The others nodded their heads in agreement as if this was not the first time they had heard Ioanneis say something like this. For Loukas, it was good to sit once again at the feet of someone he had looked up to for so long.

But it was over all too soon. When Ioanneis had finished speaking the others stood up and quickly left leaving Loukas and Ioanneis alone. There was a silence as Ioanneis looked at Loukas carefully, sizing him up for the task ahead.

“How is your family?” he asked, eventually.

“They are well,” Loukas replied.

“And how is Iounia?”

Loukas blushed, suddenly.

“My fiancée? How did you know about her? We were only betrothed a couple of months ago.”

“Oh, I have my sources,” laughed Ioanneis good-naturedly.

“Of course!” exclaimed Loukas. “You receive letters.”

“That’s right, and you haven’t answered my question.”

“Well, she was fine when I left,” he replied, although she had cried a little, as had he. Just thinking about her now had him blinking more rapidly. Ioanneis must have noticed for he changed the subject.

“Are you hungry?” asked Ioanneis. “Was the voyage difficult?”

“Yes I am, and no it wasn’t,” replied Loukas. “From Miletus we made good time, and I wasn’t sick… much.”

Ioanneis laughed. “Well then, let me get you something to eat. I’m afraid what I have will not compare to the usual fare back home in Ephesus. We get by with less here.”

“That’s fine. I’ll be back there before long…” Loukas trailed off.

“… And I’ll still be here,” finished Ioanneis, smiling. “That’s fine. I don’t mind suffering for the sake of Iēsus who suffered much worse on my behalf. And who knows? I may not be here forever. The new proconsul may grant a pardon to those of us imprisoned by the previous one…”

He prepared a small meal of bread, cheese and dried fruits. When the food was ready Loukas and Ioanneis lay down on couches and ate.

“Speaking of departures: when will the ship you came on leave?” asked Ioanneis, through a mouthful of bread.

“They intend to leave in two days. They have some goods to unload tomorrow. Then, they’ll head back to Miletus.”

“Then we’ll speak to them tomorrow. You must return with them. It is necessary for you to begin what I have called you here to do as soon as possible.”

Loukas swallowed hurriedly in order to speak. “And what is that? All this time travelling I have been wondering what it was you wanted me for.”

“Simply this,” replied Ioanneis. He moved to the other side of the room, bent down, and lifted a large, bulky scroll from its resting place on a scroll-holder.

Dima and Natasha whiled away the train trip from Nizhny Novgorod to Moscow alternately talking about the stone box with its mysterious contents and reading Nikolai’s on-going exploits from the diary. He had had a very interesting time, apparently, crossing Russian-controlled Central Asia on the Transcaspian railway. At Geok-Tepe he had seen the ruined Turcoman fortress, its mud walls pock-marked with shell holes yet dominated by a huge breach. Only four years before, General Mikhail Skobelev’s engineers had tunnelled under the wall and with two tonnes of explosives had blasted their way through, closely followed by the Russian infantry, thereby bringing about the complete desolation of the defenders. Nikolai had heard all about the victory, but it was quite another thing to see the ruins with his own eyes.

Merv, by comparison, had been occupied by the Russian army without a shot being fired only a year before Nikolai arrived there, through some secretive and rather unscrupulous diplomacy. There, in the city that had formerly been known throughout Central Asia as the Queen of the World, Nikolai had witnessed the once proud Turcoman people living under the oppressive yoke of the Russians.

From Merv the railway was only being used to ferry building materials up the line towards Bokhara, since the Russians were still in the process of laying tracks and constructing an enormous wooden bridge across the River Oxus. Nikolai managed to catch a lift on one of these goods trains and had devoted a number of pages in his diary to describing the river, once he had arrived there, and the bridge that was slowly taking shape before his eyes.

At that point, however, Nikolai had run out of pages and the diary ended.

“It’s a good thing we found his trunk and the stone box,” Natasha had commented, “or else we would never have known if he managed to get it back to Russia.”

With no further distractions Dima was left to muse about the stone box and the scroll contained within. How old was this scroll? How had it ended up in Ephesus? As a fairly typical Russian growing up under atheistic communism Dima had learned nothing about the Bible. However, he and Natasha had recently got involved with a small church that met one Metro stop away from their apartment building. The congregation had been mostly comprised of younger people and they played contemporary-sounding worship music that he and Natasha had enjoyed. And they had started hearing about the Bible. Someone usually preached every week and they had both found it fascinating to discover that the Bible was still very relevant to life in the twenty-first century. He had bought a copy – something that would have been impossible only a decade and a half before – and had been reading it ever since. He had loved the Gospels but had struggled through Paul’s letters. However, it had been the book of Revelation that had puzzled him the most. It was disconcertingly easy to read but utterly impenetrable as far as what it meant. He did not remember hearing any sermons on the book so he really was in the dark about how one was supposed to approach it. The stone box resting at the bottom of his backpack safely stowed between his feet was therefore an exciting challenge. He wanted to understand Revelation and what better way than by being involved in the study of an ancient manuscript of the book.

If that was what it really was. He was basing the identification of the scroll on three words and the fact that they reminded him of the start of Revelation. He could well be wrong.

Once they arrived in Moscow all thoughts of the stone box and its scroll were forgotten in the mayhem of getting themselves and their luggage from Kursky Station, the station they had arrived at, to Leningradsky Station, the station from which trains departed Moscow to go to St. Petersburg. This meant catching the Moscow Metro, and Dima, not having lived in Moscow at all, needed to concentrate a little. However, they only had to go one station anti-clockwise around the Brown Circle Line, from Kurskaya to Komsomolskaya Metro Station, which was the one closest to Leningradsky Station. He was eternally grateful that they did not have to change lines at any stage!

It was only when they were sitting in the McDonalds adjacent to Leningradsky Station, eating a well-deserved hamburger and fries, that he allowed himself to relax and think about what they had found on his family’s dacha.

“What do you know about the book of Revelation?” Dima asked Natasha, as she was dipping a fry into some unidentifiable sauce.

“Not a lot,” she replied, hesitantly. “There’s a lot of death and disasters, some grotesque monsters, and a happy ending – at least, for Christians.”

“Yes, that seems to be a good description. But I just remember pages and pages of graphic details. I mean, for a book with no pictures it is very visual.”

“Well, you are a graphic designer. It makes sense that that is how you would approach it.”

“True,” said Dima, with a frown. “But do those details have any meaning?”

“I don’t know.”

“I really want to find out.”

They were silent for a few minutes. Finally, Natasha spoke.

“You know, Dima, I think God really wanted us to find the scroll.”

“Really, why?”

“I don’t know.” Natasha stopped to consider the question. “Maybe the time has come for the book to be fulfilled,” she continued hesitantly. “It’s all about the end times, isn’t it?”

“Yes, I guess so.”

“Well then, start looking for death and disasters, grotesque monsters and a happy ending.”

They laughed. Dima happened to glance at his watch and realised their train would be departing soon. So they finished their meal quickly, collected their bags that had been safely stored under the table, and headed off to the station.

Once on the platform, they presented their tickets and passports to the guard waiting outside their carriage and he nodded, ripped off his portion of the ticket, and returned their passports. Once on the train, they made their way along the corridor of the carriage until they reached their coupé, the small room consisting of four beds and a small fold-away table beneath the window. It was still quite light outside, but it was already late evening – their train was an overnight sleeper – so they drew the curtains and waited to see who would occupy the remaining two beds. A woman stewardess came by with their blankets and pillows, so they paid her the small extra fee, and prepared their beds. They had been fortunate to get the two lower beds, so they sat facing one another, each reading a magazine they had purchased in the station.

Suddenly, there was a knock on the door of their coupe. Looking through the window, Dima could see two policemen standing there. He opened the door and one of the policemen stepped into the coupé.

“Baggage check,” the man said, brusquely.

Dima, suddenly very conscious of the stone box in his backpack stowed carefully up next to his pillow, began to feel a little anxious.

“Is that really necessary?” he asked.

The policeman, not appearing to be the least perturbed by Dima’s question, replied, “Yes, yes, just routine. You just need to open all your bags, we’ll have a quick look, and we’ll be on our way.”

Natasha had by this time put down her magazine. Dima could see her looking at his backpack with a worried expression on her face. The policeman must have noticed it, too, for he also looked over at the backpack.

Dima thought quickly. Standing up, he pulled out some money from a front pocket of his jeans, and placed it into the palm of his hand. Then, he reached out as if to shake the policeman’s hand.

“Look,” he said, pleasantly. “Of course you can look in our bags.”

The policeman saw the hand outstretched and shook it warmly. The money changed owners.

“Oh,” he replied, “that won’t be necessary. I’m sure your bags are fine.”

With that, he turned and quickly left the coupe. Dima, still standing, shut the door behind him. They were silent for a few minutes.

“Well done,” said Natasha eventually.

“Thanks,” he replied, a little shakily.

A few minutes later, the other two occupants of their coupé arrived: two businessmen who obviously made the journey between Moscow and St. Petersburg frequently, since they greeted Dima and Natasha, set up their beds, and by the time the train pulled out of the station they were already asleep.

It had been a fairly long day so Dima and Natasha also settled down for the night. After saying good-night to one another Dima lay back on his bed and looked at the bottom of the bunk above him. He had his backpack up near his head so that no one would be able to grab it while he was sleeping, but it still took him a while to relax enough to fall asleep. Natasha, lulled by the rocking of the train as it plunged through the gloomy Russian countryside, went to sleep quite quickly.

Dima woke first, as the train slowed in its approach to Moskovsky Station in St. Petersburg. He gently roused Natasha and they quickly packed up their things and tried to straighten their hair. The businessmen, too, had awoken and were preparing to disembark.

Moving ever more slowly, the train gradually eased into the platform and came to a gentle stop. Collecting their bags, including the now precious backpack, Dima and Natasha followed the businessmen out of the coupé and into the carriage corridor where the other passengers were now lining up waiting to leave the carriage. Eventually, they made it onto the platform and then they followed the steady stream of people walking in the direction of the station’s exit gates.

“Do you want to take the Metro home?” asked Natasha, wearily.

Dima considered it for only a second.

“No, not really,” he replied. “Let’s get a taxi.”

Outside in the square, they found a taxi driver, negotiated a suitable price, then walked over to his taxi. After putting their bags in the boot – Dima kept the backpack with him – they got in and the taxi driver started off. At one point, the taxi driver took an unexpected detour, but explained it was because they were setting up for a Paul McCartney concert to be held in Palace Square next to the Hermitage that evening. Dima looked at Natasha, thinking of the musical x-rays they had unearthed back at the dacha, but at the same time they both shook their heads. They had something far more interesting to think about now. They had managed to get the scroll safely to St. Petersburg. The question was what to do with it now.

The next morning Ioanneis woke Loukas early as the roosters were crowing in the dawn. After a quick breakfast of bread and honey they headed off to the dock to speak to the captain of the ship Loukas had arrived in. There had been a storm overnight but it had blown itself out leaving the pathways muddy and leaf-strewn. They did not speak as they walked passed the statue of Domitianus and then down the hill to the harbour. They found the captain overseeing the unloading of the cargo under the watchful eye of a Roman patrol and confirmed with him that Loukas would depart with them the next day. Then they turned around and headed back to Ioanneis’ house.

“So, what’s the scroll?” asked Loukas finally.

After showing Loukas the scroll last night Ioanneis had immediately replaced it on the stand saying that there was not enough time to discuss it then and there. They had then prepared Loukas’ bedding and retired for the evening.

“Ah yes, the scroll,” replied Ioanneis. He was silent for quite some time. Then, after drawing near to the statue of Domitianus at the top of the hill, Ioanneis stopped to look at it.

“When you look at this statue what do you see?” Ioanneis asked, suddenly.

Loukas thought for a moment then had a quick look around to see if anyone was close enough to overhear their conversation. There was no one nearby. The town was very small and most of the activity was clustered around the dock at the bottom of the hill where there were a few shops lining a tiny Agora. In the area around Ioanneis and Loukas there were a few private houses and some civic buildings such as the gymnasium to the left and baths to the right. But it was far from a bustling metropolis.

“I see a mere mortal deluded into thinking he is somehow divine,” replied Loukas quietly but with some heat.

Ioanneis smiled. “You are right to be cautious in saying such things. If anyone had overheard you would probably be very fortunate indeed to end up here on Patmos with me for good. However, you have spoken truly. Domitianus’ delusions of divinity are bad enough but he has been abusing his position of power by forcing others into believing those delusions too. I don’t think I need to remind you of our friends who have been persecuted for not going to the Temple of the Emperors. But it’s only going to get worse…”

They continued on in silence until they came to Ioanneis’ house and went inside. Once again Ioanneis went over to the scroll and picked it up.

“Loukas, this is for the churches of Asia. I want you to take this scroll and read it in Ephesus. Stay there only long enough for it to be copied, then go to Smyrna, Pergamum, Thyatira, Sardis, Philadelphia and Laodicea. In every place stay only long enough to read the scroll and for a copy to be made. When you have been to the seven churches return to Ephesus and encourage the church through what is to come.”

“Why?” asked Loukas. “What is coming?”

Solemnly, he handed the scroll to Loukas. “Tribulation,” he replied, sadly. “But then vindication will follow as surely as the dawn follows night.”

Loukas looked at the scroll with a puzzled look on his face. “So what’s in the scroll.”

Ioanneis seemed unwilling to answer the question directly. “I know that many of the young people back in Ephesus used to call me ‘the Seer’ behind my back,” he said. Loukas smiled guiltily, for he had certainly done so. “However, it’s true: God has given me the gift of prophecy which I have used in the churches over many years. Well, a few months ago I had a vision. This scroll is my attempt at putting the indescribable into words. What I heard I have reproduced faithfully; what I saw I have tried as best I could to give my impressions of the experience.”

Loukas was suddenly eager to read the scroll. He unrolled the beginning and read aloud, “ ‘The revelation of Iēsus Christos, which God gave him to show his servants what must soon take place…’ ”

Ioanneis interrupted kindly. “That’s enough for now. You can read it on the way home.”

“So, this is an apocalypse?”

“Well, it’s not like those that have been circulating recently. After all, I’ve signed it. I haven’t hid behind some important figure out of the Scriptures, trying to borrow their authority for what I’ve written. No, my authority comes directly from Iēsus Christos the Lamb of God!”

Ioanneis had got a little worked up thinking about pseudonymity and took a few moments to calm down before continuing. “No, this is a prophecy not an apocalypse. But it is somewhat like them in that there’s a lot of mysterious language and only some of it is explained. You’ll soon work out why. But you should have no difficulty working it all out. Just keep your Scriptures handy!”

Loukas rolled up the scroll. Ioanneis passed him a cloth cover and he placed this over the scroll before putting it in his bag.

“Do you know whom you were named after?” asked Ioanneis.

“Yes,” replied Loukas. “He who wrote one of the Gospels.”

“Well, you will be my evangelist sharing the good news to the churches of Asia. But I’m afraid this good news will be bitter in the stomach…”

When Dima woke up the next morning he was disconcerted to find Natasha, already awake, staring at him.

“Finally!” she exclaimed. “I’ve been awake for ages just waiting for you.”

Dima sat up and groaned as he rubbed his eyes. “What time is it?” he said, looking at the sunlight streaming in around the sides of the curtains.

“Seven,” Natasha replied. “Don’t look at the light; it’s been like that for hours.”

Dima groaned again. He had lived in St. Petersburg for over ten years now but he had never been thrilled about the White Nights.

“So,” he asked finally once he was in control of his thought processes, “what got you up so early?”

“You have to ask?” she responded.

They both looked over to the desk in the corner of their tiny bedroom where the stone box stood.

“No, not really,” Dima replied. “But what do we do with it now?”

“I’ve been thinking about that,” said Natasha eagerly. “We should show it to Zhenya.” Yevgeny, or Zhenya for short, was the pastor of their small church. “He may know someone who could help,” she continued. “Someone at the Christian University, perhaps.”

“That’s a good idea. And it is Sunday, after all.”

They had a leisurely breakfast, for their church met in the afternoon. When Natasha went out to do the shopping, Dima got out their Bible – he had neglected to take it with them to Nizhny Novgorod – and started reading the book of Revelation. He enjoyed the first chapter with its description of Jesus. The letters to the Seven Churches in chapters two and three was reasonably clear, apart from some baffling references to the Nicolaitans, Balaam and Jezebel. But things went downhill from there. The more he read the more puzzled his expression became. What on earth is this book trying to say? he thought. I hope Zhenya knows what’s going on here.

When Natasha returned he had got as far as the ‘666’ at the end of chapter 13, so he stopped reading and helped her unpack the groceries.

“It’s a mess!” he said angrily, carelessly waving a carton of eggs.

“Oh, are they broken?” asked Natasha, thinking that she had neglected to check the eggs in the shop.

“No, I’m talking about Revelation,” replied Dima, sliding the eggs into their place in the refrigerator. “I’ve been trying to read it all morning, but it’s just a complete mess.”

“Well, wait until we talk to Zhenya. He’s studied the Bible at University; he’ll know something.”

“I hope so.”

After the groceries were packed away Dima made some tea for Natasha and some coffee for himself. Then they sat at the small table in their tiny kitchen and ate some chocolates.

“Do we take it to church?” asked Natasha after a while.

“I’ve been thinking about that,” replied Dima. “I’m guessing the less we move it the better. Why don’t we invite Zhenya and Marina around after church?” Marina was Yevgeny’s wife, responsible for running the children’s programme that ran at the same time as the church service. Natasha would help her out occasionally.

“Sure.”

Once they had finished their drinks they got ready to leave. Dima locked their front door carefully and then they walked down the three flights of stairs to the ground floor of their apartment building. As he opened the security door at the front of the building he saw a bus coming down the street towards them.

“Quick,” he said to Natasha, “here it comes.”

The bus had already pulled in to the stop as they hurried across the road, but a babushka was slowly getting off, so they had time enough to jump in the back doors before they closed and the bus pulled away from the curb. There were plenty of seats at that time of day, as well as it being a Sunday, so they were able to sit together.

Dima was preoccupied with Revelation, especially that last chapter he had just read. He had heard of the expression ‘the mark of the beast’, but he had not realised there were in fact two beasts, one that came out of the sea and one that came out of the earth. Then there was the dragon in the previous chapter; but at least whoever wrote the book had provided a key for that one: the dragon was Satan, the one who had appeared as a serpent in the Garden of Eden and deceived Adam and Eve into eating from the tree of the knowledge of good and evil. It looked as though the dragon had called up the beast from the sea, so what did that make it? Instinctively, he knew that identifying the beast would help work out what the book as a whole meant.

Suddenly, Dima realised Natasha had been speaking to him. He looked up and saw that they had reached their stop. They got out in front of Vasileostrovskaya Metro station, conveniently located opposite a McDonalds restaurant. They crossed the road and lined up at the outside order window – the pedestrian equivalent of ‘drive-through’ – and bought lunch. Then, it was not a long walk to the building where their church met, eating their lunch as they went.

There were a few people already there, and some of their friends came up and welcomed them back from their holiday. Yevgeny was there but was busy talking with the worship team up the front. Dima had thought it would be better to wait until after the service anyway.

They enjoyed the service, and as usual Yevgeny’s message was worth listening to. But both Dima and Natasha had their minds on the stone box sitting in the corner of their bedroom with its mysterious scroll. So as soon as the service was over, they went straight up to the front.

“Welcome home!” exclaimed Yevgeny when he saw them approaching. He was a tall man, mid-thirties, with strong, piercing eyes.

“Thanks,” replied Dima. “We had a good time.”

“Actually we wanted to speak to you about something that happened on the trip,” said Natasha eagerly. “We found something that belonged to Dima’s great-great-grandfather; something he found in Ephesus.”

“What did he find?” asked Yevgeny. “A coin?”

“No,” replied Dima. “Look, we would like you and Marina to come over to our place for dinner and we’ll show you what we found. I’d rather not spoil it by just simply telling you about it.”

Yevgeny looked intrigued. “Let me check with Marina.”

Marina, his wife, was not far away. She was a little younger than Yevgeny with pale skin and long dark hair. After briefly conversing with her Yevgeny was back.

“OK,” he replied. “If you can wait half an hour or so, we’ll come over with you, if that’s alright.”

Forty minutes later the four of them made their way to the nearest bus stop. While they waited for a bus, Dima and Natasha spoke about their holiday, without mentioning Ephesus again. The bus, once it arrived, was more crowded than earlier; they were able to find seats for Marina and Natasha but they were not together, so further conversation was impossible.

Then, once they got off the bus right outside Dima and Natasha’s apartment building, Dima asked Yevgeny cryptically, “So, do you know much about the book of Revelation?”

“Well, I studied it a little at university, but why do you ask?”

“Just wondering,” replied Dima as he opened the security door using a three number code.

They were silent as they climbed the three flights of stairs. Dima unlocked their front door and then they were inside the apartment. Everyone took off their shoes, located appropriate slippers from the rack near the door, and followed Dima through the living room into the bedroom.

“My great-great-grandfather wrote a diary,” Dima began solemnly. “Natasha found it on a book shelf when she was looking for something to read. Apparently, when he was visiting Ephesus with some Turks there was a small earthquake. Part of a wall collapsed close to where he was standing revealing a hole behind it. And in the hole he found this.” With an air of ceremony, Dima indicated the stone box.

“Is there anything in it?” asked Yevgeny as he stepped forward to take a closer look.

“Yes,” replied Natasha. “A couple of things, as far as we can make out. Maybe more.”

Dima lifted the lid off.

“It looks like a scroll,” said Yevgeny.

“It is,” said Dima. “We’ve only looked at the very start of it but I think it’s a copy of the book of Revelation.”

With great care Yevgeny examined the scroll, his lips moving as he slowly read the Greek words to himself.

“You could well be right,” he said after a while. “It certainly starts like Revelation.” He reluctantly let the scroll go and stepped back from the box, speaking quickly. “But this is huge! This scroll looks extremely old. You do realise that Revelation was written to Ephesus and some of the churches nearby? This could be one of their earliest copies. It could even be the original. No, that would be impossible. I don’t think there are any manuscripts of the New Testament that go back that far. No, this must be an early copy, but I wonder how early? You have to take this to the Christian University. Let them roll it out properly; translate it.” Turning to Dima he asked, “How did your great-great-grandfather get it out of Turkey?”

Dima was laughing at Yevgeny’s lengthy outburst. “Well, we haven’t finished reading his diary. He was quite a character, apparently, and thought that only cowards took the most direct way home.”

“When can we take it to the University?”

“Well, I’m back at work this week, but I might be able to negotiate an early afternoon, maybe Thursday or Friday.”

“That will do nicely. I’ll work out the day and we’ll meet here. We can take it over together.”

“I’m coming, too,” said Natasha. “Marina?”

“Yes,” Marina replied, “I’ll come and keep you company.”

“Well, then,” exclaimed Yevgeny excitedly, “that’s settled!”

The ship sailed shortly after daybreak. There was a favourable wind that would have them in Miletus by nightfall so the captain wanted to get away as soon as possible. But first the Roman guards had to satisfy themselves that only those permitted to leave Patmos were on board.

Once they were under way the weather was delightful but Loukas saw none of it. He found himself a sheltered corner with enough light to read and immersed himself in the vision that Ioanneis had recorded. He began reading with great pleasure and was immediately entranced by the vision of one like a son of man – Loukas recognised the reference to the prophet Daniel – but described as if he were the Ancient of Days.[6] He knew that Ioanneis was referring to Iēsus but making it very clear that he is also God. He could feel the awe that Ioanneis had felt in seeing the one who holds the power over death and the grave and he was himself awe-struck. He could not wait to read this out to the churches back in Asia.