"What's wrong. Big Brother?" It was Yuen Biao, noticing my black expression.

"Nothing," I said.

"It's not nothing," he countered.

I sighed and filled him in.

"So you think he might be taking you away?" said Yuen Biao.

I nodded.

"I Vkish my parents would come and take me away," he said somberly.

I AM JACKIE CHAN • 65

Still one of the youngest kids at the school. And he really missed his parents; they hardly ever visited, although they showered him with presents and hugs whenever they did.

When I first realized that my life with Master wasn't going to be the easy ride I'd hoped for, I hated my dad. I resented how he'd tempted me with visits and then trapped me here for good, and I wondered how he could abandon his only son to the wolves.

I understood better as I got older. There was no way Dad could have supported me and Mom if we'd all stayed at the Peak, and he couldn't have afforded to bring us all with him to Australia. The school was what was best for me at the time.

But now—it was a puzzling, mixed-up situation. I didn't know what to think or feel anymore. I understood my father, but I resented him. I dreamed of escape, but I wanted to stay. What would I say when I saw him again? What should I expect from this unexpected reunion, and what would become of me?

All night long I turned these questions over in my head, coming no closer to finding answers. In the morning, I was given leave to prepare for my father's arrival, scrubbing myself clean and putting on my best outfit—no longer my cowboy suit, which I'd long since outgrown, but a pair of faded blue pants and a fresh white T-shirt.

Washed and groomed, I sat at the long, wooden table in the practice hall, waiting with Master for the knock that would announce my parents.

The wait was awful. I could hear Yuen Lung screaming at the other students in the background, and wished I was practicing with them rather than sitting anxiously on the hard wooden bench, afraid even to shift my posture.

There was a soft thumping on the door. Master patted me on the back and led me to the entranceway. I opened the door, and for the first time in years saw the man who'd brought me into the world.

Australia had not changed my father much. He was still the same tall, stern man of my memories, with a few more lines on his face, and a bit more color to his skin. He seemed as awkward in my presence as I was in his, and we stood there staring at one another until Master beckoned my parents in off the stoop. He and my mother stepped inside, and Mom immediately put her arm around me.

We walked to the long table and sat down, as Master signaled for tea. Father sat on one side of me, and Mom on the other, with Master at the head of the table.

"You've grown, Ah Pao," he said, his voice gruff. "Maybe you've even outgrown your name." He was right; now a skinny adolescent, I no longer deserved the baby name "Cannonball." I was more like a rifle: lean, compact, and hard.

66 • I AM JACKIE CHAN

Master looked into my face and nodded in my father's direction. His expression carried a suggestion: I hadn't seen my father for such a long time. Shouldn't I embrace him?

I swallowed and turned to Dad, folding my arms around him in an unfamiliar gesture of affection. My father responded clumsily in kind. He'd never been one for demonstrations of his feelings—the softer ones, anyway—and clearly felt uncomfortable at this display. But Master seemed pleased, and my mother positively beamed at the sight.

My father cleared his throat, as if to change the subject. The tea arrived, giving us something to do with our mouths other than talk. It was a relief.

Mom was the first of us to break the silence. "Kong-sang, how are you doing in your studies?" It was the first time she'd ever called me by my given name, and it sounded strange from her lips. Bemused, I nodded, my expression blank.

"He is doing well," said Master, saving me from having to respond. "He is not our best acrobat, or our best singer, or our best fighter—"

So much for my savior!

"—but he is sufficiently accomplished in all things, and nearly ready to advance to performance. You should be proud of your son."

Master's words were like treasure. I'd never heard him direcdy praise any of us, so hearing him tell my parents that I had been worth all of his effort brought a smile to my face. And the more I thought of it, the more I had to agree with him. All of my brothers and sisters had something in which they excelled—my brother Yuen Wah had good form, litde Yuen Biao was a tremendous acrobat, and Biggest Brother was one of the most powerful fighters. I wasn't the best at anything, but I was good enough at everything. I had no special talent—but that was a blessing in disguise. Because if I had been the best singer, then the teachers would have made me concentrate on singing. If I had been the best actor, then they might have made me specialize in acting. Instead, I got a chance to learn everything and do everything well.

My father looked at me with surprise, as if he'd never expected me to succeed.

"Oh, Kong-sang, we ar^ so very proud of you!" said my mother, squeezing me.

I was pretty proud of myself! Because the master had said something else that I'd nearly missed; he'd suggested that I was nearly ready to perform, to show off my skills in public. And that meant that my dream of the crowd, the audience cheering in the dark, was going to come true. Sometime soon. Unless . . .

Unless my parents took me away. My stomach flip-flopped, and the smile faded from my face. The dream, once so close, now gone forever.

I stared at the soft cloth slippers on my feet, suddenly wishing that the

I AM JACKIE CHAN • 67

day had never begun at all. "May I be excused?" I asked in a subdued voice. Master, deep in conversation with my parents, waved me away, and I slipped from the wooden bench to return to my brothers and sisters. They were taking a breather, their faces red with exertion. Yuen Lung was leaning against the wall, the master's cane at rest against his shoulder.

"So, Big Nose, how are Mommy and Daddy?" he said.

I ignored the sarcastic tone in his voice. "They're fine," I said.

"Are you going away, Big Brother?" piped Yuen Biao, sitting with legs outspread on the practice floor.

"Dunno," I said. "No one's said anything."

Yuen Lung laughed. "Nice knowing you. Big Nose. Don't let the door hit you on the ass when you leave."

I clenched my fists. "I ain't going anywhere." Not yet, I thought to myself.

"Yah, just admit it, you're a washout," he said. "Just like 'Big Brother' Yuen Ting."

Get angry enough, and reason and training go right out the window. Every cell in my body screamed that I couldn't pick a fight with Big Brother, that doing so would be against hundreds of years of tradition. If I so much as raised a hand in anger in his direction, any chance I had at a career in the opera was history.

Then I remembered that it was probably history anyway. So who cared?

"Listen, Yuen Lung," I said, my throat constricting in anger. "I'm not gonna let you push me into doing something stupid right now. You're still my big brother. But I swear to you, the first time I run into you outside of these walls, I'm going to kick your ass."

Yuen Lung pushed himself forward, slamming the rod hard against the wall. "You little—!" he shouted. "Ya better bring an army, shrimp, 'cause you're gonna need one."

"Don't think so," I said, with more courage than I felt.

"Yeah, I think so," said Yuen Lung, his grin suggesting he was looking forward to the opportunity. The rest of the kids gathered in a semicircle around us, horrified and eager at the same time. No one had ever committed the crime of challenging a big brother. Which is also to say, no one had ever had the guts to challenge a big brother. Until now. And so . . . the students wanted blood.

Feeling sick, I suspected they'd get it—only it was going to be mine.

"Students!" said Master, his eyes flicking suspiciously back and forth between Biggest Brother and me. We quickly dropped our hostile expressions and fell in line with the other kids. "I wish to announce a special surprise. Mr. and Mrs. Chan have brought food for a celebration feast. Today, instead of afternoon practice, we will have a going-away party!"

The assembled students screamed their approval. Even Biggest

68 • I AM JACKIE CHAN

Brother, after throwing me a final rude gesture, relaxed his scowl and cheered—food being the ultimate peacemaker at the academy.

Only I stayed quiet.

"Hey, Big Nose, send me a picture of a koala," said Yuen Kwai as he ran past me. "Or better yet—a naked native girl!"

It was all going the way I'd feared.

My opera life was over.

"Big Brother?"

Yuen Biao poked his head into the storage room, to find me sitting in my good pants on the dusty floor, my chin on my knees. I lifted a hand in greeting.

"What's wrong?"

Yuen Biao came in and sat down next to me.

"Have you ever had a dream, Litde Brother?" I said.

He cocked his head, thinking. "Sure," he said. "I dream all the time. Mosdy I have nightmares, though."

"No, I mean like something you really, really want."

Yuen Biao stared at the floor. "I really, really want to go home," he said. "Back to my parents. Like you—^you're so lucky. . . ."

"I don't feel so lucky," I said.

Little Brother looked at me in shock. "You mean, you really want to stay here? Why?"

"'Cause if I go, I won't be able to do opera. Going onstage. The lights, the audience . . . you know. Being a star."

With a strange laugh, Yuen Biao buried his face in his hands. "You think we're really going to be stars?" he said, in a voice that sounded much too c)Tiical coming from such a young mouth. "All we got to look forward to is more practice and more hurting and more screaming from Master, and maybe someday we'll get to perform, but there are dozens, maybe hundreds of kids just like us out there. And they all want to be stars, too. What makes us so special?"

I put my arm around Yuen Biao, who was sobbing gendy. "Hey, Litde Brother, don't cry," I said, trying to sound comforting. Even if I felt like joining him. "You know what makes us special? We're the best, that's what."

Yuen Biao looked up and smiled, wiping his eyes.

"And I don't care what happens. If my parents drag me away, I'll jump off the plane. I'll come back here, find you, and we'll go become stars together."

"I saw some kids doing backflips in the street last time we went to the park," Yuen Biao said. "People were giving them money."

"We're better than them," I asserted. "We could get rich!"

I AM JACKIE CHAN • 69

"No more Master," he said.

"No more Biggest Brother," I responded.

"I guess this is what you'd call a dream, huh, Big Brother?" said Yuen Biao.

I laughed. "Nah, a dream is when you eat until you're sick. And that's what we're gonna do right now." Grabbing Yuen Biao's hand, I pulled him out of the storage room and down the corridor, toward the sound of clicking chopsticks and clattering dishes that signified a party under way.

THE LITTLE PRINCE

hen I went to sit at my usual place in the middle of the long wooden bench, I was led by my father to the head of the table, where I sat next to Master facing my parents. It was the first time I'd been honored this way since my "honeymoon" years before.

The table, usually bare, had been covered with a rich red cloth. The simple dishes of stir-fried vegetables and steamed fish we were used to were nowhere to be seen; you could almost hear the wooden planks groan as they supported platters of roasted duck, huge steaming tureens of tofu-and-watercress soup, pork knuckles braised in soy, and thick yellow noodles in brown sauce. Master had opened a round jug of plum wine and was drinking small cups of it in honor of my mother and my father. In a rare gesture of magnanimity, he even poured tiny amounts in glasses for the big brothers and me, and led us in a toast.

"To our special guests, Mr. and Mrs. Chan, who have so graciously provided this feast," said Master, raising his cup. We drank from our glasses, swallowing the thin brown fluid. Yuen Tai coughed as the deceptively sweet wine burned its way down his throat, and Biggest Brother broke out into hearty laughter as he slapped his choking friend on the back.

Master ignored the faux pas. "And now, we have a special announcement about our brother Yuen Lo," he said, returning to his seat as my father rose from his.

"Master Yu," he said haltingly. "Good students of the China Drama Academy, I thank you for taking care of my son."

He put his hand on my mother's shoulder.

"I have come back to Hong Kong to do something I wish I had been able to do years ago. ..."

I tensed in my seat. This was it.

"I am bringing my wife Lee-lee to Australia."

Master nodded. The students looked at one another in confusion. And I—I found myself unable to breathe. My mother!

Mom was going to leave. I would be alone, truly alone, for the first time. And as much as I'd been embarrassed at the teasing of the other boys when Mom had visited, I couldn't imagine what life would be like without her.

I thought back to my earliest memories, of Mom ironing as I played in

I AM JACKIE CHAN • 71

the washtub. Of being cradled in her arms as she waved away mosquitoes and sang me to sleep. Of her smile, and soft hands, and gentle voice. I pushed away my plate, barely hearing my father as he continued to talk.

Yuen Lung and the other elder students looked at one another. What did this have to do with the academy?

But my father wasn't finished.

"And so. Master Yu, I want to ask a special favor of you," he said. "Since neither I nor my wife will be here in Hong Kong, I would like you to consider adopting our boy as your godson."

I gave a start and looked up. So did the other students. Adoption!

Master looked at my parents and then at me. "Though he is not the best behaved of my students, I think there is potential in this boy," he said. "I will agree to adopt him."

Yuen Lung and Yuen Tai gritted their teeth. Me, the master's godson! This was too much! But there was nothing they could do. Master had made his decision.

My heart was pounding, and my head seemed filled with noise. What could this mean? I began dinner prepared to pack my bags; now, I found myself being given a position of unprecedented honor.

But one thing was certain.

I was here to stay.

We finished dinner in shocked silence. As the dishes were being cleared and the other students drifted away in groups, discussing the weird new state of events. Master took a small red box out of his pocket.

"Yuen Lo, come over here," he said, opening the box. Inside was a glittering gold necklace. I bent my head, and he fastened it around my neck. "From this day on, you are like a son to me," he said solemnly. My parents looked on with unrestrained pride.

I guess I should have been happy. After all, I would have my chance to make it on the stage, to win the applause I knew was mine. And I would do it not as a no-name player, a ragged unknown boy, but as Master's godson—the "prince" of the school. It was a position any of my big brothers would have given their left arms to receive.

But I was beginning to remember the challenge I'd thrown down to Yuen Lung, when I was certain I was on my way out If he had it in for me before, this would be the straw that would break the camel's back—^and possibly my neck.

I looked at Master. I couldn't think of a single thing to say.

"Thanks," I mumbled.

I was doomed.

EVERYTHING HAS ITS PRICE

o there was a black cloud over my head as I set off with my parents for the airport. I knew this would be the last time we'd all be together for many years, but the swift turnarounds of the past few hours had left me—usually known for having a big mouth to go along with my big nose—completely speechless. Dad must have been doing well in Australia, because instead of the bus, we took a taxicab, the three of us squeezing into the backseat.

My mom wanted to tell me how much she would miss me. I wanted to reassure her that I'd be okay, that I'd make her proud. My dad wanted to say something, anything that would seem appropriate, given the situation, but I guess he was as tongue-tied as I was.

Finally, he broke the silence. "Will you be all right alone in Hong Kong?" he asked.

I nodded again.

And then Mom, overcome with emotion, lurched forward and told the cabdriver to stop. With a jerk, he pulled the car over, turning to shout at my mother for scaring him half to death and nearly causing an accident—but she'd already thrown the door open and pushed her way outside. Neither Dad nor I had any idea what she was doing, and after a moment's hesitation, we both made a move to go after her.

Then we saw her weaving back through the crowd, in her light wool coat and cotton dress, her hands weighted down with a red plastic bag of fruit. She struggled to pull it into the cab after her, and then almost shyly presented it to me. I looked at the bag, and at my mother, and it was like a dam broke inside me. I let the bag slip to the floor of the cab and hugged her, squeezing her with all of the force of my thin young arms. I felt a soft pressure on my shoulder, and I knew it was my dad, adding his own restrained display of emotion to the tableau.

The car pulled into the airport, with the three of us still in that pose. Dad paid the driver and sent him off after retrieving Mom's baggage from the trunk. And then there was an endless wait on line, and papers exchanged and passports stamped, and then the parade down the long white corridor to the exit gate. Mom's bags were heavy; after all, they contained everything she owned. I struggled with two of them, while my fa-

lAMJACKIECHAN • 73

ther carried the others, refusing to let my mother trouble herself even with the lightest of her possessions.

"This is it, Kong-sang," my father said, as we reached the queue of strangers bound for Australia. Though some of the passengers were foreigners, many were Chinese: men, women, and even little boys and girls boarding the plane, headed for vacations or new lives in that unusual, unfamiliar place. Mom embraced me one last time, and told me that she would always be thinking of me, to take care of myself and not worry her. Dad patted my head, and then pressed some money into my hand, telling me to use it to buy admittance to the airport viewing platform, where I'd be able to watch their plane take off. He probably suspected I'd just use it to buy candy, but not this time.

I watched as the back of my father's head disappeared through the gate, and saw my mother briefly turn her face and smile, her eyes full of tears. And then I ran like hell down the corridor to make it to the viewing platform, caroming off tourists and knocking businessmen aside in my rush. The man at the turnstile looked at me like I was a dangerous lunatic; still, he took the cash I handed to him, and simply watched as I pounded my way up the spiral staircase.

I was feeling very strange. Like there was a wall of stone in my heart, blocking something significant. I didn't know why, but getting to the platform in time to see my parents' plane take off was suddenly the most important thing in the world.

Breathless and rumpled, I made it to the top of the tower just in time to see my mother and father's plane taxi down the runway. I was alone on the platform, and the thick double-paned glass cut off the sound of the engines and the screech of rubber tires. In utter silence, the plane picked up speed, lifting its nose, and pulled away from the ground, fighting against gravity.

Then, with a roar, it turned and elevated, and disappeared into the clouds.

It was only then I realized that tears were running in uncontrollable streams down my cheeks. In that screaming silver bird were the last ties I had to my blood and my memories, my innocence and my childhood. There was an entire world in that plane. A world I no longer belonged in, and that I'd never see again.

And what did I have instead?

I fingered the gold chain around my neck, lifted the heavy bag of fruit over my shoulder, and headed back down the stairs, back to the only place I could now call home and the only people in Hong Kong that I could call my family.

When I got to the school, Master squeezed my shoulders roughly and welcomed me back. Then he lifted the gold chain from around my neck.

74 • IAMJACKIECHAN

"With you running around so much, you might lose this," he said. "I will keep it in a safe place for you."

And he did. So safe that I never saw it again.

I didn't see my mother for many years after that. Not until I'd reached adulthood, and by then she was older, a litde grayer and more fragile than in her prime, as I'd known her. We kept in touch, through the tapes that she and Dad continued to send, and occasionally through letters. My mother had no education and couldn't read or write. So every time she sent me a letter, I knew it wasn't in her hand. But if anything, that made it even more special to me, because to get that letter written, she'd had to spend her free time cooking or cleaning for other people, doing special favors for people who were better educated than she was. They would write her words, and they would read what I sent back, explaining the characters and describing the scenes I related. I thought of her crying as I told her of the exhausting practices and the struggles I had to gain the skills I needed to succeed. I never told her about the beatings, the discipline I received from Master and from the big brothers, but I knew she knew. And when I read her words, or listened to her voice on tape, sitting in the storage room behind the back staircase that led to Master's quarters, I'd cry too, letting tears run down my face just as I had when I saw her and Dad fly away that day at the airport.

It was always the same. "I miss you," she would say. "But you're a big boy now. Listen to Master. Be good. Make sure you keep clean, and eat well." But the heart in those words shone through, building a bridge that crossed an ocean, a bridge of shared tears.

As I grew older, and more unwilling to lose myself in my emodons, I started to set the taped messages aside, promising I'd listen to them later. The tapes gathered dust and piled up in the storage room. I never found the dme. And one day, I realized they were gone. To this day, I don't know what happened to them. There's a piece of my history with my parents that will always be missing. All my fault, and something I'll always regret.

When I arrived back at the school, I realized that I was stepping across the threshold as a different person from when I left. My master's declaration of my adoption couldn't help but change things somehow. Or would it? Maybe it was just a gesture to comfort my mother before she left. Maybe everything would go back to the way it was before. Like normal— if it could ever have been called normal.

As usual, I was wrong. It was dinnerdme when I arrived, and the long table was lined with expectant faces awaiung the evening meal. We'd eaten so much at our lunch feast that you'd think we wouldn't be hungry

I AM JACKIE CHAN • 75

again so soon, but food was so precious at the academy that we'd eat Hke goldfish, until we died of overstuffing, if we had the opportunity. There were plenty of lean times to make up for the very few chances we had to act like pigs.

All eyes were on me as I walked toward the table, headed for my customary place.

"Yuen Lo," said Master. "Where are you going?"

I stopped in midpace. "To sit down and eat, Master."

"You are now my godson," he said. "From now on, your place is here."

I walked like a zombie to the seat next to Master, as Yuen Lung shifted his weight over and made room.

"Pass Yuen Lo the fish, Yuen Lung," said Master, returning to his meal. Biggest Brother looked like he wanted to dump the dish over my head. If we'd been in a cartoon, there would have been steam shooting out of his ears. But with Master a few feet away, he didn't dare make a move to hurt me as I knew he wanted to—a kick under the table, a stray elbow jab, a chopstick in my eyeball.

This, of course, only made him angrier. It was remarkably fun to see him so frustrated, sitting there like a big fat rice cooker building up steam. As I took the head of the fish—the best part—and started to shovel food into my mouth, I decided that I could get used to this godson thing. I couldn't have gotten deeper under his skin if I'd slapped him across the face.

We were still without a new tutor, so Master declared that, following dinner, we'd have a special practice to make up for what we'd missed during the day. As I stretched in preparation for the workout, Yuen Lung went to take his position at the front of the hall. I felt his foot come down on my toes with crushing weight as he crossed before me. I stifled a yelp.

"So, shall we bow to you now. Your Highness?" he whispered at me under his breath. "Guess you're now the 'Prince.' That's my tribute. Plenty more where that came from."

Not good.

And then training began.

"Today we will focus on forms and positions," said Master. We groaned to ourselves. This was one of the most difficult aspects of Chinese opera: the striking of poses that had to be held with absolute stillness, often for minutes at a time. Sometimes, during practice, if Master thought that we were slacking off, he'd call out "Don't move!"—and, regardless of the position in which we found ourselves, we would have to freeze until he gave us the signal to continue. An unlucky student who moved a limb would instantly pay the price of Master's displeasure, as the cane came out and slapped the errant arm or leg. Stumbling out of position would demand even worse punishment: kneeling at the head of the class, pants down, as

76 • I AM JACKIE CHAN

Master deliberately and harshly applied the rod to the wretched student's backside. And, of course, the rest of us would have to maintain our frozen positions.

We stood quietly in our rows, wary of what the practice would bring.

"Yuen Lung, lead the students in basic forms," Master said, crossing his arms, his eagle eyes ready to spy the tiniest of errors.

"Okay, let's go!" yelled Biggest Brother. "On my count: one, two, three, four!" Punch, sway, turn, punch, kick . . .

"Stop!" shouted Master.

We froze in place, our legs high in the air. Master walked slowly around us, watching for signs of movement. Seconds, then minutes went by, and our brows began to sweat, knees to feel weak. Somehow, everyone managed to stay upright on one leg.

"All right!" he said, finally, "Everyone can move—except Yuen Lo."

The other students collapsed in relief, dropping their legs and panting. I gritted my teeth and remained immobile, my heart pounding and my muscles stiffening. Master stood expressionless before me, ignoring the increasingly desperate look on my face. And then he motioned Yuen Lung over.

"Bring me the teapot, Yuen Lung," he said. Biggest Brother nodded and headed for the kitchen, moving with unusual slowness. By the time he returned, I could feel my stomach beginning to buckle, and my left leg, the one on which I was balancing, was a mass of pain.

Master poured himself a cup of tea, and sipped it, relaxing as his face was framed by steam.

I wanted to scream.

"Now that you are my godson, you have to set an example for the others," he said, finishing the tea and pouring himself a second cup. "When your brothers and sisters train, you will train twice as hard. Everything they learn, you will learn twice as well. You will make me proud, because that is what I expect from my own children."

He then leaned over and carefully balanced the cup of tea on my leg.

"If you spill any tea, you vrill be punished," said Master. "And godson—^when you are punished, you will receive twice as many blows."

Standing to the side with the other students, Yuen Lung suddenly looked like it had turned into the happiest day of his life.

The teacup fell, splashing hot liquid as it shattered.

Master looked at me, shaking his head in disappointment, and making a familiar gesture with his stick.

At least kneeling on the floor gave me a chance to rest my legs.

Things only got worse from there. During handstand practice, Yuen Kwai was caught taking a covert rest, and was hit twice with Master's stick—once for each leg that was leaning against the wall.

IAMJACKIECHAN • 77

Then Master came over to me as I displayed my perfectly erect upside-down form . . . and hit me four times.

"Since you are my godson, his failure is your failure, and his punishment is your punishment," said Master, "h is up to you to set a better example."

Yuen Lung couldn't help but let out a sudden guffaw at my plight, and Master came over and gave him a quick slap with the rod.

And then /got two more slaps.

"Do you see, Yuen Lo?" said Master. "From now on, every time there is punishment, you will be punished . . . only twice as much. I am trying to teach you the merits of responsibility. You must share your brothers' and sisters'joys, and also share their pain. Now, everyone, take a rest."

I knew better by this time than to think that Master's words applied to me. Legs straight, I thought to myself. Arms steady. No wobbling. Legs straight, arms steady . . .

UP IN SMOKE

fter the most excruciating practice of my life finally came to an end, I was completely aware of the fact that my princehood was going to make me miserable. At this rate, would I even survive to graduation? For the first time, I thought seriously about gathering my things and quietly slipping away into the night, as Yuen Ting, the first Biggest Brother, had done years ago. Yuen Biao's suggestion of becoming a street acrobat didn't sound like a bad idea.

I slumped down against the wall of practice hall, exhausted. After the workout, Master had left the school to go meet friends, giving us a rare evening to ourselves. It was hours yet until lights out, so I headed for the storage room to catch some quick shut-eye.

Dazed and stumbling, I almost didn't recognize the rough hand that grabbed my shoulder as I made my way down the corridor.

"What is it?" I mumbled, listlessly turning around. It was Yuen Lung. Oh no, my clouded brain thought. Not now.

But Biggest Brother didn't look like he wanted to fight. Not this time, anyway.

"It's Yuen Biao," he said. "He's sick. You'd better come over."

Out in the courtyard, a crowd of students were crouched around Litde Brother, who had his hands clenched tighdy to his stomach.

"What's wrong, Yuen Biao?" I said, shaking the sleep out of my head.

"My stomach hurts," he said tearfully.

"Ah, you probably just ate too much," said Yuen Tai. "I saw you cramming cookies in your face at lunch."

Yuen Lung gave Second Biggest Brother a punch on the shoulder. "Shut up, moron," he said. "Master and Madame won't be back until late. If the kid croaks, we're gonna be neck deep in crap."

Yuen Tai gulped. "Uh, maybe should we give them a call."

Biggest Brother rolled his eyes. "Yeah, anyone know where they are? Besides, /ain't gonna be the one to interrupt Master on his night out."

I helped Yuen Biao sit up. "What's good for a stomachache?" I asked.

The other students muttered to one another.

"Ice cream?" said Yuen Kwai. Yuen Lung slapped him in the head.

Then Yuen Wah spoke up. He was a thin kid whose mastery of martial arts form had us all in awe. When we did "freeze" practice, he'd still be as

IAMJACKIECHAN • 79

motionless as a statue long after the rest of us collapsed. He could stand on his hands indefinitely. In fact, once when Master told us to take a break, he kept on going, head to the ground, until someone realized that he'd actually fallen asleep upside down.

It was all almost inhuman, and it lent a kind of supernatural air of authority to his words. He didn't speak a lot, but when he did, we listened. Even Biggest Brother. "I heard that smoking cigarettes was a good way to cure an upset stomach," he said. Other kids quickly chimed in that they'd heard that, too.

The problem was that the only cigarettes to be found anywhere at the academy were owned by Master and Madame. And so, to save Yuen Biao's life, someone would have to sneak into their room and steal some smokes!

A discussion began as to who would be the best candidate for the job. Yuen Lung and Yuen Tai refused, on the grounds that such a matter was best handled by juniors. The younger students responded that it was the duty of the elders to take care of them, so they shouldn't be doing it, either.

Meanwhile, Yuen Biao moaned.

"I got it," said Yuen Lung, finally. "Prince Big Nose'll do it."

"What?" I sputtered. "Why me?"

"He's your best friend," said Biggest Brother. "Besides, figure it this way: if anyone else is caught doing it, you're gonna get punished too, right? So why get two people screwed when you can take the heat on your own?"

I had to admit, the logic was inescapable. After some more halfhearted attempts to pass the buck, I threw up my hands and went back inside.

Master and Madame's quarters were in the same building as the school, down the corridor from our complex. My heart was pounding as I crept down the hallway. Opening the door, I went into their bedroom and saw several packs of smokes scattered on Madame's bedside table. One of them was open and half full. I grabbed it like a lifeline, pulled out a few cigarettes, and headed back toward the corridor.

Then I had a revelation: when they got back, Madame would surely realize that cigarettes were missing, and the jig would be up. But what if I took an entire pack? She'd probably just think she'd dropped it on the floor. She probably wouldn't even notice it was gone at all. Feeling clever, I put the pilfered cigarettes back and slid one of the plastic-wrapped packs off the tabletop into my palm. Holding it concealed in my hand, I tiptoed back out of the room, feeling stupid; it's not like there was anyone to witness my crime, so why was I sneaking around like—like a thief?

Even so, I walked down the hall looking over my shoulder, as if at any moment Master was going to jump out of the shadows and whip me silly. When I finally made it downstairs and out to the courtyard, I felt like a

80 • I AM JACKIE CHAN

conquering hero. I'd gone into the lion's den and smuggled smokes out from under his nose.

Well, not really. But I'd certainly done something that even big-shot Biggest Brother was too chicken to do.

"Damn, he did it," said Yuen Lung, seeing me walk forward, the pack held high above my head like a trophy. "Didn't think you had it in you, Big Nose."

It was backhanded praise, but from Biggest Brother it was like honey from a rock. He took the pack from my hand and pulled off the plastic wrapper, tossing it to the ground. Soon, all of us were sitting in a circle in the courtyard puffing on cigarettes, Yuen Biao's troubles mostly forgotten in our eagerness to try out this new vice.

"How's your belly, baby?" said Yuen Lung to Yuen Biao, his lit cigarette dangling from his lower lip. He was the only one of us who managed to make it look kind of cool. As for the rest of us, one of the younger sisters accidentally burned herself and threw her cigarette away, screaming. Yuen Kwai was rolling on the ground coughing and hacking. Yuen Tai couldn't keep his lit, and setded for holding it in the corner of his mouth, hoping that the other big brothers didn't notice he was faking.

To me, the whole experience was like inhaling car exhaust, but I wasn't going to be the only one to say so. Meanwhile, Biggest Sister, comforting the girl who got burned, told me that smoking was a filthy habit.

"Ah, we shouldn't be wasting good smokes on girls anyway," I responded, disgusted that she didn't appreciate the glory of my victory. She picked up Litde Sister and stalked off to put some soy sauce on the injury. They were soon followed by Yuen Biao, whose face had slowly turned green as he sucked on his smoke. It wasn't long before he bolted from our circle and ran indoors, headed for the kitchen sink.

He came back a few minutes later, wiping his mouth on his sleeve. "I think I feel better," he said. We broke down in laughter, and he puffed out his cheeks, pouting. "Stop it, guys, I told you I was sick!"

We were all feeling a little queasy by this time, so after declaring that the cigarettes were the smoothest ones we'd ever tasted (not to mention the only ones), we crumpled up the empty pack and carefully picked up stray butts and other evidence of the big smoke-out. "Ahh, nothing like a good smoke before bed," said Yuen Tai.

Yuen Kwai and I looked at each other. "Whatever you say. Big Brother," said Yuen Kwai, stifling a chuckle.

"Lights out in ten minutes," shouted Biggest Brother. And we prepared to setde in for the night.

It was 3 A.M. when we were woken by a pounding on the door to the pracuce hall.

I AM JACKIE CHAN • 81

"Dammit, Big Nose, we're screwed" muttered Yuen Lung, kicking his blanket away. "I thought you said he wasn't gonna figure out we took 'em."

I was in a state of panic. How did Master know? Did we leave something incriminating lying around in the courtyard? My earlier paranoia seemed justified. It was like magic. Master had eyes everywhere.

The door opened and Master walked in, his face blank. "Stand up and form a line, hands out, palms up," he said. We quickly arranged ourselves in order of seniority, Yuen Lung at the head and the littlest brother at the end. Using the tip of his rattan cane. Master flipped over each of our blankets in turn, searching for the missing cigarettes—not knowing, maybe, that all of them had long since been smoked.

He then turned back to us and studied the line, examining our faces, each in turn. There was a half-empty pack of cigarettes in his hand.

"I thought you said you put the loose ones back," whispered Yuen Kwai out of the corner of his mouth, as Master turned his attention to the htdest kids.

"I did!" I whispered back. Didn't I?

Master gazed at the head of the line. "Some of Madame's cigarettes have been stolen," he barked. "There is a thief here. Who is it?"

No one spoke.

Master went to Yuen Lung and looked at him full in the face, tapping his cane against one palm.

And then Yuen Lung, in an act of nicotine-fueled courage, asked Master a question. "Master, how do you know they were stolen? Is it possible they just got lost?"

Master shook the half-full pack and thrust them into Yuen Lung's face. "This is not the way Madame keeps her cigarettes," he said, his voice icy.

I looked out of the corner of my eye at Master's hand and flinched. Several sticks jutted out of the pack. But instead of the familiar tan filters of Madame's fancy American cigarettes, white stubs showed. In my rush to leave the scene of the crime, I'd put the cigarettes back in the pack upside down.

"Now, I will repeat myself. Since you seem so interested in how I take care of my property, perhaps you know what happened to it. Yuen Lung, who stole my cigarettes?"

"I don't know," he responded. Master quickly struck him three times with the cane.

He then went to Yuen Tai, who answered the same. He, too, received three blows.

Next in line was Biggest Sister, who looked furious at being included in this disaster. She was usually the sweetest of girls, always protecting the younger kids and taking care of us when we'd suffered particularly hard beatings. Not this time.

82 • I AM JACKIE CHAN

Master turned to her assuming she, like the others, was not going to talk. But as he lifted his stick, she pulled her hands away. "I know who did it, Master," she said. "It was Yuen Lo." Her finger pointed direcdy at me, halfway down the line. Master's gaze followed the accusing digit, and his brow creased in fury.

Girls! I thought to myself, clenching my fists. Can't trust them worth a damn.

Master walked slowly over to me and grabbed me by the shirt. The others watched as he pulled me across the hall and over to the long wooden dinner table.

"Yuen Lo, which hand did you steal with?" he asked.

I thought quickly. If I was going to lose a hand, it might as well be one I don't use as often. "The . . . the left, Master," I responded.

"Put your left hand on the table," he said.

I complied, trying not to shake. Master raised the cane and hit me hard, five times. Because the back of my hand was against the hard wooden surface of the table, each blow felt like a hammer, bruising my knuckles while simultaneously raising thick red welts on my palm. Somehow, I managed not to scream, or even wince.

WTien the beating was over, I released my breath and rubbed my throbbing hand. I wouldn't even be able to make a fist for days. But I'd gotten off easy. Five blows wasn't even twice what Yuen Lung and Yuen Tai had received.

Master stopped me before I could turn and walk away. "Yuen Lo, which hand did you smoke with?" he said.

I closed my eyes and whispered, "My right." Swallowing, I put my other hand down on the table and took another five blows on that palm.

Master turned and left the hall. The first day of my princehood was over.

Biggest Sister turned out to be right after all.

Smoking really was bad for your health.

THE CHOSEN ONES

guess I deserved what I got. I forgave Biggest Sister later, when she helped me tie strips of cloth soaked in ice water around my hands. But it was a long time before Master let any of us forget the crime. It seemed like he'd figured out that we'd all shared in the ill-gotten gain of my thievery, and so he ran us ragged, extending our practices by hours, pushing us to the very limit of our endurance.

And then, finally, a few months later, he made an announcement over dinner that served partly to explain why he was driving us so hard.

"Students, I have trained you for many years, and your skills have become nearly acceptable," he said. The words were as close to words of praise as Master could come. "But you are not training in order to please me," he said.

We looked at one another in silence. That was news to us.

"No, you are working for a much greater goal, and a much more demanding group of critics," he continued. "The audience! Because when you make a mistake before me, you may suffer punishment, but when you make an error before them, you damage your reputation, and the reputation of the school and its master. This is not something that will heal as easily as a bruise. And that is why you have been working so hard these past few weeks. Because when you step on the stage, even for the first time, you must be perfect. And that time is coming soon."

The dream. Applause, the cheering of the crowd, fame and glory. It was about to come true!

Master told us the date of our first public performance, which would take place at the theater at Lai Yuen Amusement Park—familiar ground. He explained that each of us would play important roles during the show—some of us behind the scenes, working the curtains and shifting props, others assisting with makeup and costumes, and still others in the chorus that would play crowd scenes and fill the ranks during battles.

But a select few—the best and most skilled of us—^would be placed in positions of special honor. They would be the school's stars, performing each opera's heartbreakingly difficult leading roles.

These chosen ones would stand at that grand altar of communion between player and audience: center stage. For the brief space of an opera

84 • I AM JACKIE CHAN

turn, they would command the attention of a mob of rapt worshipers, becoming princes and emperors and heroes—and gods. Upon hearing Master's words, each of us knew in our hearts that this, and only this, was what we wanted, that any other place in the repertory would be second-best, and thus, nothing at all.

We practiced with extra determination that evening, knowing that Master would be announcing his selections in the morning. Each of us tried to catch his eye, although it was unlikely that a single night's work would alter an opinion formed after years of observation. Afterward, we prepared for bed, cursing ourselves for mistakes we remembered from months gone by, or congratulating ourselves for recollected moments when we'd brought a tiny smile to our master's face.

"Lights out!" shouted Yuen Lung on schedule, and we setded into our blankets. But none of us could sleep.

"Hey, Big Nose," whispered Yuen Kwai. "Who do you think got it?"

I knew what my guesses were: Biggest Brother, of course, because he was the school's best fighter, and because he was Biggest Brother. Yuen Tai would probably be selected as well. Yuen Wah, certainly. But I didn't want to say anything for fear of being overheard. Clustered together as we were for warmth, a private conversation was impossible. "I dunno," I said.

"I bet you got it," he said. "You're the prince, right? How could he not pick you?"

I thought for a moment. Was Yuen Kwai right? I was Master's godson. But ever since the cigarette incident, he'd barely spoken to me and treated me with no particular favor. "He'll probably not pick me just to spite me," I said.

I felt a sudden sharp pain in my ankle as something heavy hit me. It was Yuen Lung's foot. "Hell!" he said. "How many times do I have to tell you to shut up when other people are trying to sleep?"

"Sorry, Big Brother."

"Sorry, Big Brother."

We pulled our blankets over our heads and tried to doze off. It took a very long time.

The morning sun seemed especially bright the next day, filling the practice hall with light. We stood in our rows, hands at our sides, listening to Master with undivided attention.

"I will now announce the students who have been selected for our performance troupe, which will be known as the Seven Litde Fortunes," he said.

So there would be seven lucky students. Seven chances to be a star.

"Each of you, as you are called, please come to the front of the room. Yuen Lung!" he said, looking at Biggest Brother. Yuen Lung stepped forward, swaggering like there'd never been any doubt.

I AM JACKIE CHAN • 85

"Yuen Tai!" Again, no surprise.

"Yuen Wah! Yuen Wu!" Our school's reigning king of martial arts stances joined Yuen Lung in line, followed by another older boy who was one of the academy's best singers.

"Yuen Kwai!" Yuen Kwai gave a jump and looked up. Grinning like an idiot, he walked up to join the line. Just two more, I thought. Two more shots.

"Yuen Biao!" As disciplined as we were trying to act, the sound of Yuen Biao's name triggered an involuntary buzz of whispering. Little Brother was one of the youngest of our student body; for him to be selected as one of the stars of the school was outrageous. But, we had to admit, he was a natural acrobat, capable of twisting his small body into positions we could only dream of, as comfortable in the air or upside down as we were upright and on our feet.

There was just one position left, and dozens of qualified candidates. I was sure I'd lost. I was destined for a future of lurking in the wings, or carrying spears. I was going to be a nobody. And all of my father's ambitions for me to become a great man, all of my spodight dreams, were for nothing.

"Quiet!" shouted Master, silencing the muttering. "There is still one more member of our troupe to be named." And we all leaned forward, our mouths slightly open, anticipating the call.

"Yuen Lo, step forward."

My mouth dropped open. Me! He'd picked me!

I bolted from my position and ran forward. Out of sheer ecstasy, I did a forward handspring on my way to the front of the room. Master looked surprised at my impromptu stunt, but smiled benignly.

The seven of us stood proudly by Master, our backs straight, our faces fixed in wide smiles.

"Fortunes, bow to your brothers and sisters," said Master. We bent at the waist and dipped our bodies low. "Students, welcome the Seven Little Fortunes of the China Drama Academy."

And, as disappointed as they were, our siblings broke out into cheers. They were proud of us. They were happy for us.

It was our first moment of applause, but certainly not our last.

SMALL FORTUNES

n the small world in which we traveled, we Fortunes were stars. Not only were we the academy's elite, acknowledged by all as the best and the brightest, but we also bore the responsibility of keeping the school alive, because it was our performances that generated the academy's only revenue. And so, being selected for the troupe was an unquestionable honor, a status that carried no negative stigma—unlike being the master's godson and the prince of the school.

Over the years, the ranks of the Seven Litde Fortunes constandy changed. Students came and students left, and Master filled the absences according to his whims. Soon after we were chosen, Master quickly selected seven students as alternates, who would fill in for our roles when we were sick or when we formed a traveling company. (Unspoken, but understood, was the fact that if any of us well and truly screwed up, there were always seven eager bodies right behind us, waiting for their own turn in the spotlight.)

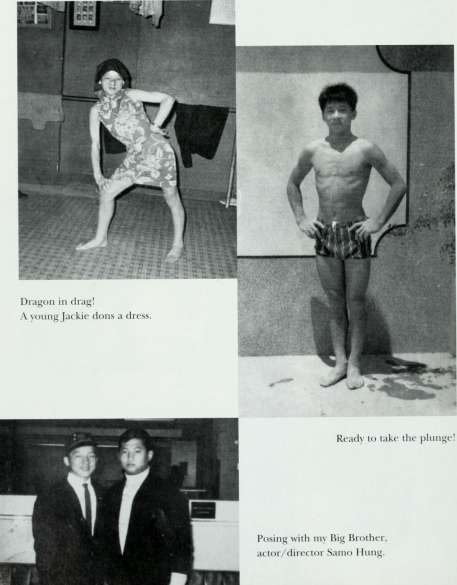

Upon our being named to the Fortunes, a new phase in our training began. All of our practice and working out was just the raw material of our art—a basic foundation. We had learned very little about opera itself and had never been given parts to play or roles to inhabit. But even as we sweated out our exercises. Master and the other instructors had been observing us carefully, noting subtleties in style and form, evaluating our body types, and imagining the result that puberty might have on our voices. A husky student like Yuen Lung was destined to portray kings and warriors, like the great General Kwan Kung. My moderate build and agile reflexes made me a natural for roles like Sun Wu Kong, the Monkey King. And a thin, delicate boy like Yuen Biao might be doomed to play female roles, which historically had always been filled by men. Times had changed; though there were still many more boys than girls at the academy, the days when women were considered a curse and banned from the stage were gone, and Master had accepted progress with relatively good grace. However, boys still had to be girls when necessary, since the Fortunes were chosen for our talents rather than our gender. With his bulk. Biggest Brother would have made a ridiculous—or rather, terrifying—girl, so

I AM JACKIE CHAN • 87

he dodged the bullet. And my voice, though considered one of the better ones at the school, was luckily of the wrong range for female songs. We mercilessly teased Yuen Biao and others who were stuck with feminine parts, telling them how pretty and sexy they were until they cried or threw fists.

The truth was, though, that the chance to play any starring role— even in woman's clothing—was a thrill that exceeded anything we'd experienced to date. But there were other fringe benefits to being a Fortune. On days when we had pleased Master with a particularly outstanding rehearsal, he would take us out for a meal of dim sum. For those of you who don't know Chinese food, dim sum, which means "a little bit of heart," is a wonderful way of eating. Instead of ordering food from menus, you sit at your table watching as silver carts roll by, loaded with small dishes, dumplings, cakes, sweet buns, and bowls of mixed delicacies. If you see something you like you simply point, and it's placed on your table—no mess, no fuss, no waiting. It's a glutton's paradise: immediate gratification of your appetite, without even having to move from your seat. The food comes to you, you pick it, you eat it. It's that simple.

And compared to the bland stuff served at the academy, anything different was as good as a feast. Of course, anything we did with Master, even dim sum, had its own set of disciplines and rituals. The first time Master treated us, we sat enthralled at the sight of the rolling food, eager to grab anything that came within range. But when Yuen Kwai reached out his hand to point to a tasty-looking dish of dumplings, Master drew his chopsticks like a sword and rapped him lightly on the knuckles. "I will order for you," he said.

Yuen Kwai winced and sat back, subdued.

Master waved a waiter over and told him to bring seven bowls of roast pork over rice. The waiter nodded and glided off to the kitchen. Meanwhile, Master began selecting his own meal from the splendid array of dim sum specialties that paraded by us, a look-but-don't-touch vision.

We knew better than to complain, and roast pork with rice was better than nothing at all—a lot better, because as far as I'm concerned, Chinese roast pork is one of the great culinary treasures of the world. Marinated in barbecue sauce and five special spices and roasted in long strips, it comes out of the oven moist and flavorful, with a deliciously sweet red glaze. We never got it at the academy, where meat was as rare as a day without practice.

So when we got our heaping bowls of steamed rice, crisscrossed wdth slices of pork, lightly crisp on the edges and so tender inside, our mouths watered. We took our chopsticks and lightly set the pieces

88 • I AM JACKIE CHAN

of pork aside, preferring to eat the rice, rich as it was with inherited flavor, before consuming the dehcacy. Then, a sHce at a time, we ate the pork, savoring each chew as if it were the most precious of gourmet foods.

As usual, there was never enough. And through the remainder of lunch, we were expected to sit quietly, drinking tea and watching Master eat his fill. My belly was outraged that I had stopped putting food into it, and I stared glumly at my empty bowl, wishing for a miracle. Then I realized that a miracle wasn't necessary: after all, I was in a restaurant. And even if Master wouldn't let me order any of the treats that continued to circle us so temptingly, he couldn't possibly object to my getting another bowl of rice. At the school, the prepared dishes were gone by the time they reached the littlest of our brothers and sisters, but rice was the one thing that never stopped flowing. It wasn't uncommon for us to make a meal out of just steamed white rice and soy sauce.

And so I did something that seemed very normal at the time. I raised my hand and signaled a waiter, pointing to my empty rice bowl. The other students looked at me like I was crazy, but Master said nothing as the waiter came and padded a large, fluffy scoop of rice into my bowl. I mixed the rice up carefully, to soak up any last bits of roast pork gravy, and ate it quickly and happily. Yuen Lung and the others looked on with envy, but none of them had the guts to ask for their bowls to be filled, too. As a result, I was the only one to go home to the academy with my hunger satisfied and my stomach full.

"You litde pig," said Yuen Lung, as we prepared for afternoon practice. "I can't believe you ate two bowls."

"Ah, you just wish you'd had the balls to ask for seconds yourself," I said.

"Screw off," Biggest Brother said, throwing a punch in my direction. I weaved past him, laughing. Things could have gotten uglier, but Master had arrived at the practice hall, and we hastily separated, running to our assigned positions.

The workout that day was grueling. Master ran us through every routine in our repertoire, throwing in sudden "freezes" or calling for us to practice at double time, then triple time. There were no breaks, and every group of moves we completed led immediately to a new and more difficult set of commands. Finally, Master waved his cane, signaling the end of the workout.

"Damn, that was crazy," said Yuen Kwai, breathing heavily. Yuen Biao slumped to the floor cross-legged, too tired even to talk. I, meanwhile, had built up a raging appetite, despite my double portion at lunch. Dinner awaited; there was no time for rest or idle conversation.

"^^^^^^^B ''^ ** f^

^

^,^ #

1^

-U^'

,mK

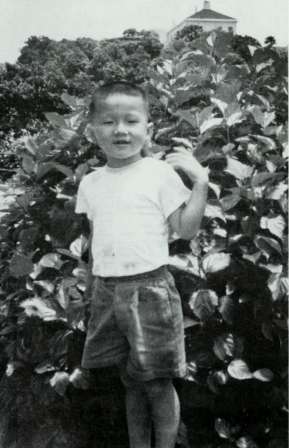

GROWING UP ON THE GROUNDS OF THE FRENCH AMBASSADOR'S MANSION ON VICTORIA PEAK.

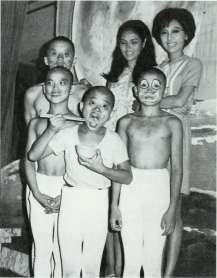

I'm fourth from the right, posing with the rest of the Seven Little Fortunes.

I'm in the second row, far left,

with three other members of

the Seven Little Forttmes:

(from left) Yuen Biao, Ytien

Mun, and Ytien Bo, and two

vmidentified female fans.

Here I am (second row, center) smiling for the camera during my Chinese opera school days.

With four of my fellow bald-headed (Chinese opera school classmates: (from left) Me, Yuen Wah, Yuen Mini, \uen Tai, and \nen Mo.

<VJk

44^

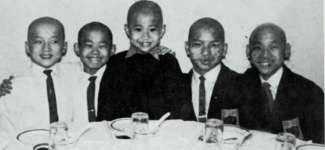

Posing witli my Big Brother, actor/directt)r Samo Hung.

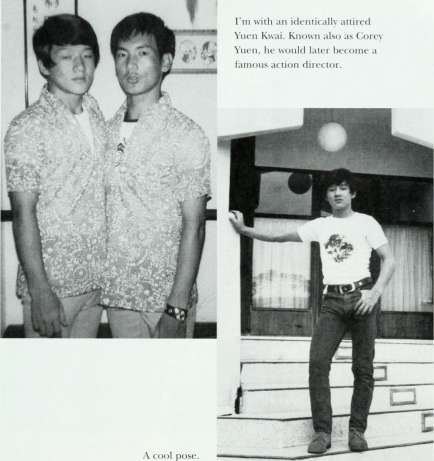

Till with an identically attired Yuen Kwai. Known also as Corey Yuen, he would later become a famf)iis action director.

A cool pose.

Theater owner and philanthropist Sir Tang Siu Kin presenting to me a momento after Fearless Hye?ui broke all-time box office records in Hong Kong.

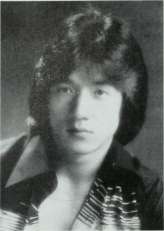

Here'^ an early "glamour" magazine shot of me. I look like 1 should be disco dancing instead of kung fu fighting.

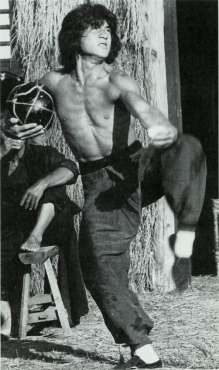

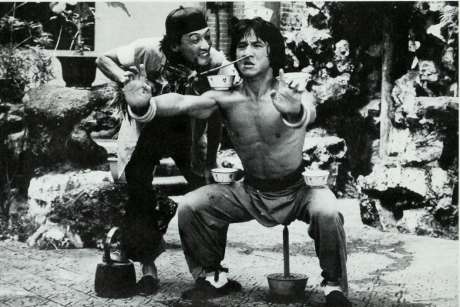

Some of my favorite scenes from one of my first big hits:

Drunken MasUr.

t^-:'

With The Young Master, my first film for Golden Hanest, I took the things we'd

worked on in Siiake in Eagle's Shadow and Drunken Master to their limit.

After that, it was dme for something new: a jotirney to the West. . . .

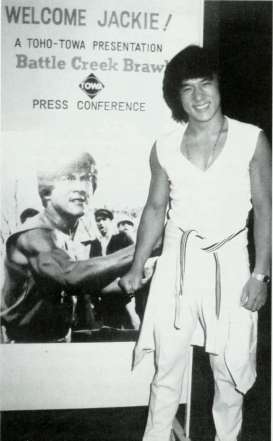

WELCOME JACKIE/

A TOHO-TOWA PRESENTATION

Battle Creek Brawl

PRESS CONFERENCE

My first two attempts at making it in America were disasters. I may be smiling in this photo—taken at a publicity event for Battle Creek Brawl —but I was screaming on the inside.

Years later. The Protector,

my second tiy at the big time

Stateside, was no better. It

did give me inspiration for

my greatest action successes,

though— Police Story and

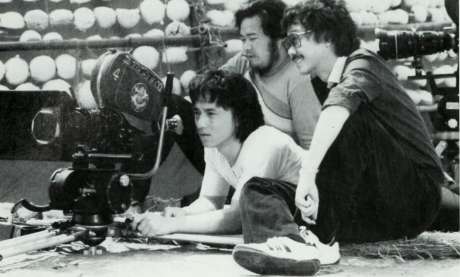

Checking out a shot—the "Bun P\'raniid Fight" seqtience—on the set of Dragon Lord with WiUie.

f

h

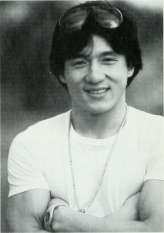

Ready for success! This plioto

was taken around the time of my

first attempt to break into the

American movie market.

n

i

Another shot from Dragon Lord.

IAMJACKIECHAN • 89

Then Master tapped me briskly on the shoulder with his rod. "Yuen Lo, you continue practicing," he said. "After all, you ate more at lunch, and so now you should be stronger than the others. Everyone else, join me at the dinner table."

I gasped. The other Fortunes smacked me on the back as they passed. "Food's gonna taste great after all that sweating," shouted Yuen Tai.

"More for the rest of us," said Yuen Kwai.

They were heardess.

"Yuen Lo, I would like to see some high kicks. Begin," said Master as he took his seat at the head of the table.

And then he turned to the cook, who was laying plates of food down and arranging chopsticks, and said, "Please make sure there is plenty of rice."

Heartless!

If there's one thing you can say about Master's brand of discipline, it's that at least you were rarely tempted to make the same mistake twice. But it wasn't as easy to learn from example. If it was difficult enough for me to resist temptation when so much food was around, for Yuen Biao, the dim sum outings were like extended torture. He would watch the carts pass with the eyes of a drowning man catching sight of land, or a dying desert survivor spotting an oasis. In particular he was tormented by the trays of pastries and other sweets, so close and yet so far.

One day it all became too much: as a cart loaded with sponge cake passed, he involuntarily yelled out an order. The waiter placed the cake on the table and moved on, as all of us, even Master, looked at Yuen Biao in shock. Realizing the enormity of what he had done, he burst into uncontrollable tears and wouldn't stop even when we returned to the academy, despite the fact that the cake sat at the table uneaten. For a change. Master didn't even have the heart to punish him.

As Yuen Biao sniffled, sitting by himself in the corner, Yuen Kwai shrugged without sympathy. "He should have at least eaten the cake," he said. I punched him in the shoulder and went to comfort Little Brother.

But as I mentioned before, the best thing about being part of the Fortunes was simply getting the opportunity to perform—to revel in the joy of the spotiight and drink in the appreciation of the audience.

Because my voice was fairly good, after a few performances in which I took supporting roles, I soon began training for my first lead part: a star turn in an opera performed only on special occasions, such as weddings or birthdays. It was a showcase role, and one that I learned with relish.

90 • I AMJACKIECHAN

since when I performed it, all of the other stars in the troupe were forced to act as my subordinates. Even Biggest Brother and Yuen Tai were just soldiers in my army, while Yuen Wah played the squire who held my horse.

Because this opera was performed so rarely, it was a while before I had the chance to do it live. When the day finally came. Master told me that I shouldn't feel nervous, that I was very well prepared for my debut, and that the audience was sure to be appreciative. I didn't need him to tell me that. My entire body was charged with excitement; the lines blazed in my head like letters of fire, and my voice sounded strong and loud as I warmed up backstage. I was so deep in character that I took to gesturing importantly at my servants, demanding my robes and my headpiece and admonishing Yuen Kwai for not finishing his makeup earlier. Yuen Lung, adjusting his armor, looked like he was considering clobbering me with his spear, but the backstage of an opera is crowded and busy, and the curtain was about to rise. There wasn't time or room to beat me properly; that would have to wait until after the show.

And then Master stage-whispered the order to be silent. My big turn, my premiere as the king of the theater, was about to begin. Holding the hem of my robe to my hip, I marched out of the wings, my other arm before me in a martial stance, and walked out before the lights.

I sang, and the audience roared. I ordered my armies to charge, and all the big sisters and brothers rolled from the wings in response, obeying without question. When I shouted "Halt!" they stood in formation, shouting "Yes, sir!" in unison. And when I reviewed my troops, they bowed down before me, me, the king of the theater. Whatever I did, people clapped and cheered. I was a hit!

And then I looked offstage, and saw Master standing stiffly in the wings, his cane in hand, an expression of mute disapproval on his face.

What did I do wrongl I thought to myself. Suddenly, I didn't want to leave the stage—not just because I was enjoying myself so much, but because I knew that Master had found fault with me, and as soon as the curtain went down, I would pay for whatever error I'd made. But I couldn't delay the inevitable, and after I'd sung my last note, and the armies at my command rode off into the sunset, the curtain came down.

The king of the theater was gone. Long live the once and future king, my master.

"Come here, Yuen Lo," he said, his voice icy.

"You're gonna get it now. Big Nose," said Yuen Lung, poking me with the butt of his spear as he passed. I winced and walked over to Master.

"Hands out, palms up," he said. And then he hit me, five sharp blows.

"Master, what did I do wrong?" I said plaintively, reviewing my performance in my mind.

I AM JACKIE CHAN • 91

"Nothing," he said. "You were very good. But I want you always to remember this: no matter how well you perform, you must never become too proud. There are others on the stage with you, and you are as dependent on their abilities as you are on your own."

And with that, he left me standing, still in costume, to direct the breakdown of the set and the storage of our props.

MY UNLUCKY STARS

esides the occasions on which we were hired to perform off-site, usually in odd locations and with makeshift stages, we put on most of our shows at the stage where we'd had our first taste of the opera, the theater at Lai Yuen Amusement Park. After a few months of performing, we had gained enough of a following that we would occasionally be recognized in public—pointed to on the street, or even approached by fans. This would always put Master in a terrific mood, and didn't hurt our egos either, though after the incident after my debut, all of us were careful not to show our pride too much.

But it is Chinese tradition that every period of good fortune is always followed by an equal and opposite stretch of bad. Our months of seemingly effordess perfection lulled us into a false sense of confidence. Chinese opera is so complex that there are literally thousands of things that can go wrong. Well, several months into our show business careers, it seemed like all of them began going wrong at once.

I remember when the bad luck started. I'm not the most superstitious guy in the world, but I have to say, I began to believe in spirits—and their temperamental natures—after our miserable run began.

And of course, it all turned out to be my fault.

One of the chores we did at the school was the tending of the ancestor shrine. The shrine, which contained tablets and statues dedicated to relatives of Master Yu, as well as opera performers long past, was in a position of honor at the far end of the practice hall. Before each performance, Master would have us bow and shake incense before the shrine, appealing to the ancestral ghosts to look favorably upon our efforts and to give us luck and skill and easily impressed audiences.

Taking care of the shrine was an honorable duty, but a painstaking one. There were dozens of small icons to dust, and old incense to dispose of, and offerings to place in properly respectful position. Everything had to be arranged just so, or there would literally be hell to pay. Because I'd been adopted by Master, he soon decided that it should be my special responsibility to care for the shrine; as he reminded me, these were my ancestors too, even more so than the rest of my brothers and sisters.

I knew I should have felt fortunate, but the truth was, I thought that the entire job was a pain in the ass. The tablets and statues and incense

I AM JACKIE CHAN • 93

pots were sacred items, and it was essential that they be treated with appropriate reverence. But after sitting for a week or so in the practice hall, they were inevitably covered with dust, and to clean them properly meant getting on your knees, leaning down, and brushing them off gendy with a feather duster.

As the rest of the students were ordered to go clean up the courtyard— it was a nice sunny day, so outdoor duty was almost a pleasure—I was left on my own in the hall, duster in hand, and facing a task that would take hours to complete.

I sighed, and evaluated the job at hand. My attitude toward the objects in the shrine was a practical one. Sure, they were sacred and everything, but they were also dirty, and they needed to be made clean. There was a quicker way of getting this done, and I wouldn't have to break my back or bruise my knees to do it, either.

I headed for the kitchen and got a damp rag, and then carefully removed all of the icons from the shrine and stacked them in a pile on the floor. WTiistling while I worked, I gave each statue a good scrubbing down, spit-shining them to a polished gleam. And then I heard footsteps behind me. It was our new tutor, arriving early at the school to discuss our progress with Master.

"What are you doing?" he shrieked, seeing me sitting cross-legged on the floor, wiping an ancestral tablet like it was an old pot or pan. "Put those down at once!"

I nearly dropped the tablet, then set it down next to me and scrambled to my feet. "I didn't mean it!" I said, looking wildly around for signs of spiritual disapproval. For some reason, the shock in his voice had triggered a flood of guilt in my conscience. "I'm sorry! I'm sorry!"

The teacher began lecturing me on the need for respect, while looking nervously out of one eye at the scattered statues and tablets. I dropped to my knees and began putting the icons back in place.

"Teacher, please don't tell Master," I said to the tutor in a frightened voice. It was bad enough to have heaven and hell angry at me; I didn't want the powers of Earth on my back, too.

The tutor agreed, wanting to get away from the shrine as soon as possible. Once the icons were back in place, I made a deep and heartfelt bow to the shrine. Accept my apologies and forgive me for treating you with such disrespect, I pleaded silendy. And please don't let Master find out, or I could be joining you up there a lot sooner than you'd like.

Teacher made good on his word and didn't tell Master, but the ways of the spirit world are mysterious and subtie; the ancestors found other means of expressing their displeasure.

Ironically, in our next performance, I was assigned to play one of a set

94 • I AM JACKIE CHAN

of five ghosts—a small but crowd-pleasing supporting role. Makeup alone wasn't enough to express properly the ghastliness of the undead, so each of us had to wear a wooden mask that completely covered our faces. The problem was, the masks were really made for adult performers, not young prodigies like us. They fit loosely on our heads, no matter how tighdy we tried to Ue them, and the tiny eyeholes were set a litde too widely apart for us to see properly. When the performance was already under way, and our cue was about to come, I was still fiddling with my mask, trying to get it to stay in place.

"Sheesh, Big Nose, what's your problem? Stop screwing with your face and get over here!" said Yuen Lung, standing with the other four ghosts at the entrance to the stage. The music that signaled our supernatural arrival began, and I scrambled to my place in line, willing the mask to hold.

No such luck. As we walked out into the lights, our arms extended, I realized that the mask was slipping dov^Ti—completely blocking my vision. I couldn't adjust the mask while onstage, so I whispered a brief prayer to whatever stage gods there might be that I'd be able to perform the scene blind. And for the first few steps in our routine, everything seemed to be going okay, until a move in which all of us ghosts were supposed to turn around and jump forward in unison.

The leap seemed to take longer than expected, and I nearly fell over as my feet hit the ground. I heard muffled gasps around me, and I realized in horror that I'd jumped entirely off the stage, almost into the laps of the front row of the audience.

Adjusting my mask with one hand, I quickly scrambled back up, hoping against hope that Master had not noticed.

On our way offstage, the other ghosts refused even to look in my direction, and even after the performance they wouldn't talk to me. I understood the reasons: not only had I messed up a perfectiy good scene, but I'd broken our string of performances without errors. I'd snapped the good-luck chain. No one wanted to get too close to me, because my aura of misfortune might rub off, infecting the entire troupe. Even Yuen Biao seemed scared to get too close to me, though he whispered a word or two of sympathy from several arms' lengths away.

Besides, standing between me and Master's eventual explosion of rage was probably unhealthy. Each night, after our performance. Master would tell us to sit on the edge of the stage as he discussed the evening's show with any of his friends who had attended. This was a nerve-racking time for us, since any offlianded mention of a flaw in the program would result in Master pushing back his chair, ordering the sinner into his presence, and instandy delivering retribution with his cane, with the number and severity of the strokes proportional to the degree of the crime.

Falling off the stage was about as big a mistake as one could make, so I sat alone on the end of the line of students, my heart in my throat, wait-

I AM JACKIE CHAN • 95

ing for the moment when Master would throw back his chair and call out my name.

Surprisingly, it never came. Master's friends had nothing but compliments to offer about our show, and so, after bidding them farewell. Master contentedly told us to line up and march back to the bus station.

No one would sit next to me on the bus, so I was left to puzzle out what had happened on my own. I'd never escaped punishment for a mistake before. It seemed like a stroke of good luck, but I knew better. A feeling of dread came over me as we took the long ride home.

Something awful was about to hit. And I was right there, at ground zero.

By the time we set off for the amusement park the next afternoon, I was a mass of anxiety. Would the bus drive off the road, or explode? Maybe I'd be struck down by a falling set, or take a mistimed leap onto someone's outstretched spear. There seemed to be a shadow over everything I did. The spirits were toying with me now, but their ultimate revenge was sure to come sometime soon.

Well, that day's opera featured me in only a very small role—a one-line cameo, in which I would enter, shout a command to the troops, and then exit grandly offstage. Maybe I'd dodge the bullet again.

Once I got backstage, just to make sure that my performance would be perfect, I prepared everything in advance. There would be no mistakes tonight, if I could possibly help it.

My part was small, but my costume was complex: an ancient and splendid set of robes, embroidered with dragons. Once I'd put them on, they were difficult to take off. So, a good hour before the show began, I went and relieved myself, and began the arduous process of getting into character. I carefully shook out the robes, counted the pieces, and checked for stains and funny smells. I stretched myself out and examined my ears and teeth. And I painted my face carefully, making sure there were no stray streaks or unusual splotches.

Satisfied that everything was in order, I got into my robes and headdress. The only thing I didn't put on was the elaborate beard that completed the costume, because it was so hot and itchy.

Finally ready, I sat stiffly in a chair, waiting for the show to begin. Just one line. What could go wrong?

And then there was a tap on my shoulder. I shook my head, realizing that I'd fallen asleep. I hadn't gotten to bed until late the night before, worrying about the state of my soul. The heat and pressing weight of the heavy robes must have put me out like a light. I looked up, and saw Yuen Tai, fully dressed for his entrance, his eyes wide with panic in his painted face. "The curtain is open, dammit!" he whispered through gritted teeth. "Get out there!"

I struggled upright and calmed my nerves, and then strode regally

96 • I AM JACKIE CHAN

onto the stage. "Go!" I shouted in a deep, warlike voice. "Kill them!" And I spun on my heel to make my exit, stroking my beard for effect.

My beard? There was nothing there! I'd forgotten the beard backstage!

Sweating profusely beneath my robes, I lifted the hem and husded off into the wings.

This time I'll be pounded for sure, I thought. It was almost a relief.

But once again, after the performance. Master failed to pull me out of line.

Worse luck yet! I'd escaped two beatings in a row. It was clear that disaster was looming, somewhere right around the corner.

"Students, today we will premiere a new opera: one that you have practiced often, but never had a chance to perform in public," said Master, his voice booming through the practice hall. "Yuen Lo—"

I froze at the sound of my name.

"—this will be your chance to impress us all!" he finished, smiling in my direction.

Oh no! We were going to be performing an opera about the God of Justice, the judge whose wisdom was so great that his decisions were sought out by god, devil, and man alike.

It was a wonderful opera.

And it starred me.

Justice was indeed at hand, and there was no doubt in my mind that the spirits had been waiting for this moment of maximum irony to strike.

Well, I resolved, I'd show them! Just because they were dead didn't mean they could push me around. I'd somehow manage to escape their vengeance, even if it killed me.

All the way over to the theater, I recited my lines to myself and reviewed the preparations I'd have to make. The outfit worn by the God of Justice was even more complicated than the one I'd had to put on the day before. In addition to the heavy robes and thick face paint, the costume included four pennants attached to my back on stiff rods. These pennants made it almost impossible to sit down once the costume was put on. It was a blessing in disguise; there'd be no sleeping on the job this time.

As I struggled into my outfit, Yuen Lung grabbed me and swung me around. "Listen, asshole," he growled. "You'd better not screw up tonight. I don't know how you got to be so lucky, the last two days. But if you make another mistake, I won't wait for Master to give you your medicine. I'll doctor your ass myself."

I couldn't deal with his threats at that moment, and so I impatiendy waved him away with one hand as I applied makeup to myself. When I was finished with my paint and my costume, I put my hands on my hips and looked at myself in the full-length backstage mirror. I looked fear-

I AM JACKIE CHAN • 97

some, my pennants streaming behind me, my face perfectly painted, and my thick black beard lending my face an appropriately impressive demeanor. The final touch was my tablet of office, a carved slab of wood carried in one hand that indicated my status as a high-level scholar.

I was convinced. Tonight would be perfect; I would avoid my fate after all. And with that, I carefully removed my beard and placed it back in the properties box, setting the tablet down near the stage entrance, where I wouldn't misplace it.