ONE

‘Mum,’ said Fitzherbert. ‘Why do I look different from all the other goslings on the farm?’

He did, there was no denying it. He was larger than the rest, his feet were bigger, and his neck was longer.

‘You are different,’ said his mother.

‘Because I’m an only child, d’ you mean?’

The other geese all had five or six goslings apiece, but Fitzherbert alone had hatched from his mother’s clutch of eggs.

‘An only child in more ways than one,’ she said. ‘I doubt if there’s another bird like you in the whole wide world. All these other youngsters will grow up to be ordinary common or garden geese, but not you, Fitzherbert my boy.’

‘But I’m a goose like you, Mum, aren’t I?’ said Fitzherbert.

‘No,’ said his mother, ‘you are not.’

She lowered her voice.

‘You,’ she said softly, ‘are a swoose.’

Fitzherbert coiled his long neck backwards into the shape of an S.

‘A what?’ he cried.

‘Sssssssh!’ hissed his mother, and she waddled off to a distant corner of the farmyard, away from all the other geese.

Fitzherbert hurried after her.

‘What did you say I was?’ he asked.

His mother looked around to make sure they were out of earshot of the rest of the flock, and then she said, ‘Now listen carefully. What I am about to tell you must be a secret between you and me, always. D’you understand?’

‘Yes, Mum,’ said Fitzherbert.

‘You are old enough now to be told,’ said his mother, ‘why you are unlike all the other goslings on the farm. They are the children of a number of geese, but all of them have the same father.’

‘The old grey gander, you mean?’

‘Yes.’

‘But isn’t he my father too?’

‘No.’

‘Then who is?’

‘Your father,’ said Fitzherbert’s mum, and a dreamy look came over her face as she spoke, ‘is neither old nor grey. Your father is young and strong and as white as the driven snow. Never shall I forget the day we met!’

‘Where was that, Mum?’

‘It was by the river. I had gone down by myself for a swim, when suddenly he appeared, high in the sky above. Oh, the music of his great wings! It was love at first flight! Then he landed on the surface in a shower of spray and swam towards me.’

‘But I don’t get it, Mum,’ said Fitzherbert. ‘What was he? Another sort of goose?’

‘No,’ said his mother. ‘He was a swan.’

‘What’s that?’

‘A swan is the most beautiful of all birds, and your father was the most beautiful of all swans.’

‘What was his name?’

‘He didn’t say. He was a mute swan.’

Fitzherbert thought about all this for a while.

Then he said, ‘So I might be the only swoose in the world?’

‘Yes.’

‘There aren’t any other swooses?’

‘Sweese.’

‘Eh?’

‘When there’s more than one goose, you say geese. So more than one swoose would be sweese.’

‘But there isn’t more than one. Just me. You just said so, didn’t you?’

As mothers do, Fitzherbert’s mum became fed up with his constant questions.

‘Oh, run away and play,’ she said.

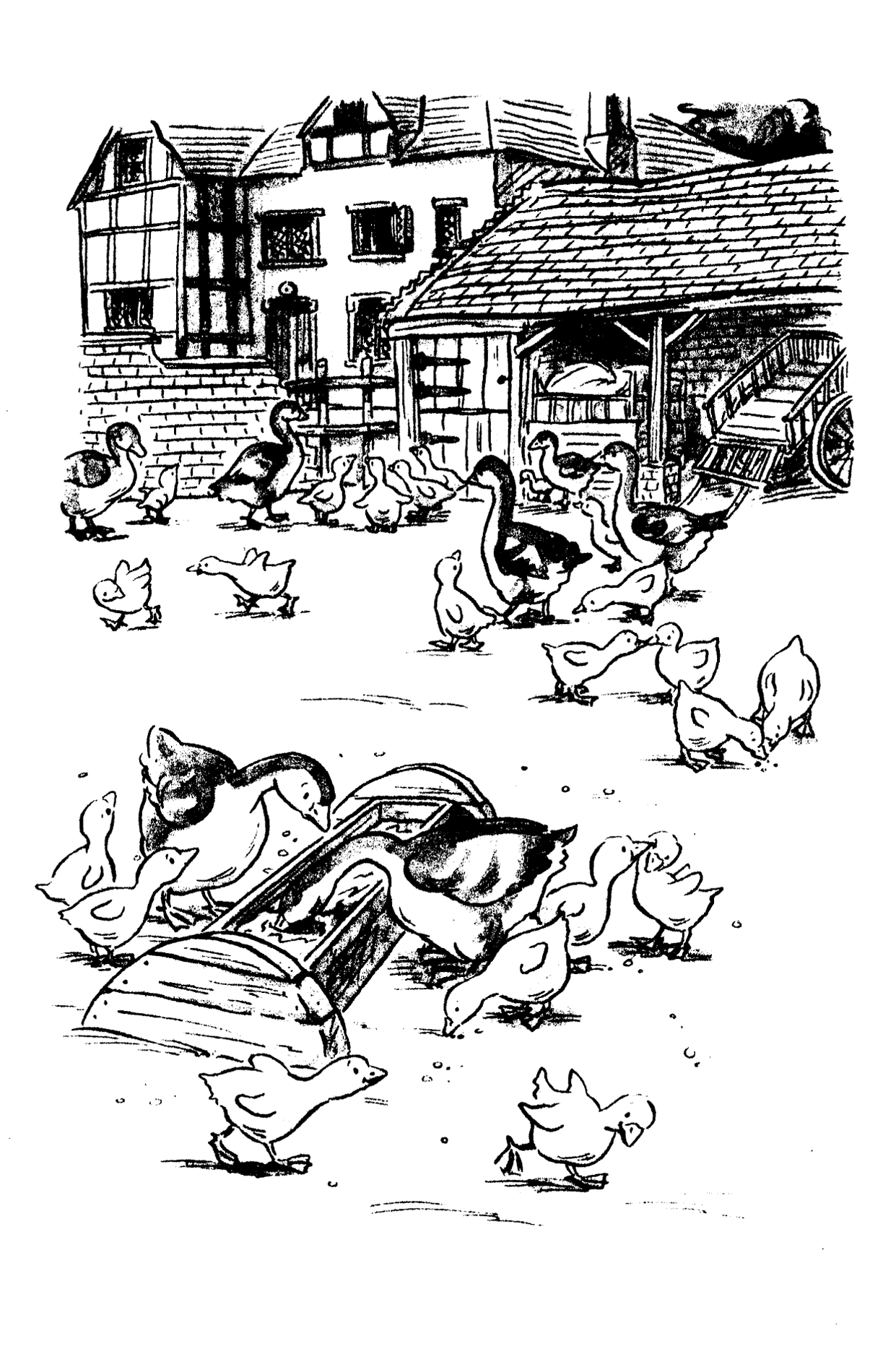

But playing with the other goslings wasn’t a lot of fun for Fitzherbert. Already they had noticed that he was different. They poked fun at him, calling him Bigfeet or Snakyneck, and they wouldn’t let him join in their games.

Time passed, and Fitzherbert began to grow his adult feathers. Often, as he thought of his father swooping down from the sky on whistling wings, he flapped his own and wished that he too could fly. Farmyard geese like his mother and the rest couldn’t, he knew – they were too heavy-bodied to get off the ground. But swans could. How about a swoose? And the more he thought about his father, the more he wanted to meet him. So one day he decided to go down to the river by himself. He would say nothing to his mother about it, but just set off when she wasn’t looking.

He had never before been out of the farmyard, and he was not at all sure what the river looked like, let alone where it was, but luck was on his side. He walked across a couple of fields and there it was, in front of him!

Fitzherbert looked at the wide stretch of water, winking and gleaming in the sunlight and chuckling to itself as it flowed along. Never in his life had he swum upon anything but the duckpond at the farm, but this – this is the place for swimming, he thought, and he waddled down the bank and pushed off.

He paddled about in midstream, looking up at the sky, hoping that a snow-white shape would come gliding down to greet him.

Instead he suddenly turned to see a whole armada of snow-white shapes sailing silently downstream towards him. There must have been at least twenty swans, all making for this stranger who dared to swim upon their river. Their wings were curved in excitement, and the look in their black eyes was far from friendly.

Oh, thought Fitzherbert, as the fleet of swans approached, all now grunting and hissing angrily, oh dear, I really must fly!