TWO

As Fitzherbert swam hastily away from his pursuers, he spread his wings and beat them madly on the water in an effort to increase his speed. Harder and harder he flapped, and then he felt his body lift a little so that now, instead of swimming, he was slapping his broad webs on the surface in a kind of clumsy run.

Suddenly he was airborne, and the swans, satisfied that they had seen off the stranger, did not trouble to follow.

It wasn’t much of a flight, that first effort. For perhaps a quarter of a mile, Fitzherbert laboured along only a few yards above the water, and then, tired out by his efforts, flopped back down into the river. He looked anxiously around, but to his great relief, there was no sign of the swans. Nasty, bad-tempered creatures, he said to himself. I wasn’t doing them any harm. Why, my dad might have been one of that lot. I don’t know that I want to meet him after all.

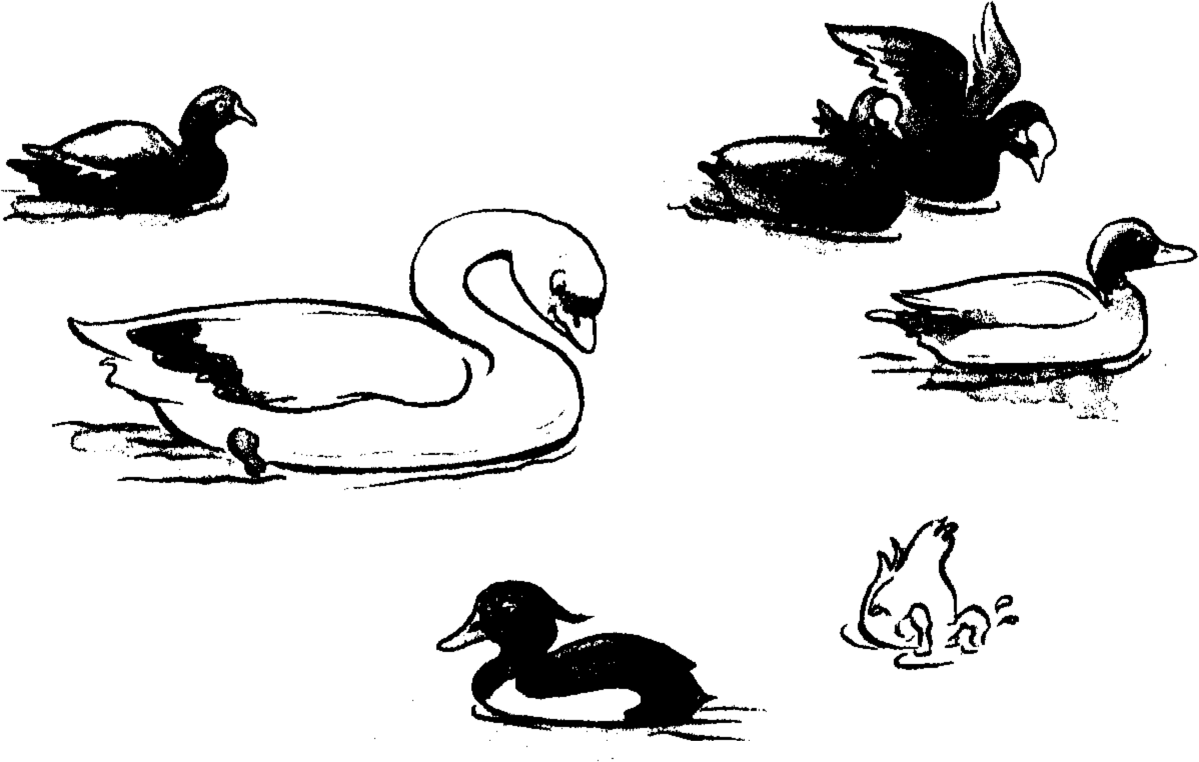

He swam on, looking about him with interest. He could see other birds on the water – different sorts of duck, and moorhen, and coot – and there was a sudden brilliant flash of colour as a kingfisher darted across. There were people on the river too, in rowing boats and punts, and one very long thin craft shot by with eight large young men pulling at their oars, while a ninth much smaller man steered and shouted at them through a kind of tube held to his mouth.

‘In! Out! In! Out!’ he called, and the blades dipped and rose as one.

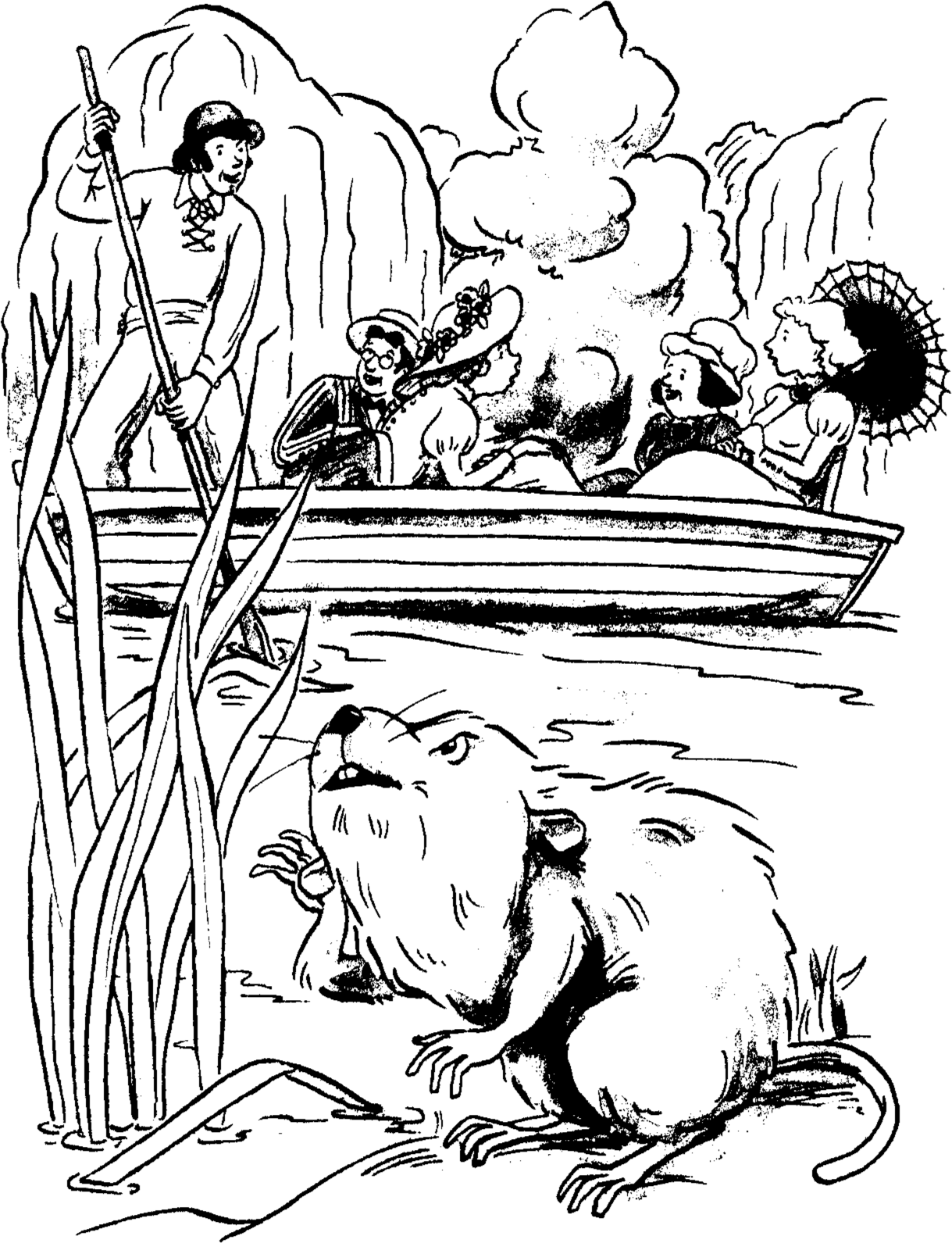

Fitzherbert drifted dreamily with the current, enjoying the sunlit scene, when suddenly a sharp voice cried, ‘Avast there, you landlubber, or you’ll run us down!’

Startled, the swoose looked down to meet the angry gaze of a small water vole.

‘Oh, sorry!’ said Fitzherbert. ‘I’m afraid I wasn’t looking where I was going.’

The vole did not answer, but swam to the bank. Fitzherbert followed.

‘I suppose you couldn’t tell me?’ he said.

The vole turned at the mouth of his burrow.

‘Tell you what?’ he said.

‘Where I’m going?’

The vole stared beadily at the swoose.

‘Are you feather-brained?’ he said.

‘No, I’m Fitzherbert.’

The water vole shook his blunt head as though to clear it.

‘Tell us something,’ he said. ‘You come sailing along without any regard for the rule of the river, and then you go and talk a load of rubbish. Anyways, I never in my life set eyes on a bird like you before. What are you?’

‘I’m a . . .’ began Fitzherbert, and then he thought, oh no, I promised Mum I wouldn’t tell.

‘I can’t really say,’ he replied.

‘You don’t know what you are,’ said the vole. ‘You don’t know where you’re going. Next thing, you’ll be telling me you don’t know what river this is.’

‘No. I don’t.’

‘Then you don’t know the name of that town you can see, down at the end of the reach?’

‘No.’

‘Nor the castle on the hill above it?’

‘No.’

‘Nor who lives in that castle?’

‘No,’ said Fitzherbert. ‘I’ve never been outside our farmyard before. But I’d be very grateful if you’d tell me.’

‘You’re lucky, young fellow,’ said the vole. ‘You’ve come to the right chap. Now, if you’d asked a moorhen, or worse, a duck, you’d have been wasting your breath. But there isn’t much that I don’t know about this here stretch of the Thames.’

‘The what?’

‘The Thames. That’s the name of this river. Most famous river in all England, I’d say. And that town yonder is Windsor, and that’s Windsor Castle above it. Now then, surely you know who lives there?’

‘No.’

‘Why, the Queen, of course.’

‘Oh,’ said Fitzherbert. ‘What’s a queen?’ he said.

The water vole sighed deeply.

‘You’re a bright one,’ he said. ‘She’s only the most important person in the land, that’s all.’

At this point a pair of swans appeared in midstream.

Fitzherbert backed into a clump of reeds and kept his head down.

‘Now d’you see those swans?’ said the vole. ‘They belong to the Queen, they do, like every other swan in the country. Royal birds, swans are.’

Oh, thought Fitzherbert, I wonder if sweese are? I bet she’s never seen one.

‘This queen,’ he said. ‘What’s she called?’

‘Victoria. She’s been Queen for donkey’s years, she has.’

‘Donkey’s ears?’ said Fitzherbert.

‘Why, ’tis ages ago she lost her husband.’

‘Couldn’t she find him again?’

The water vole sighed and continued.

‘And ever since she’s shut herself up in that castle. Always dressed in black, she is. The Widow of Windsor, they call her.’

‘How do you know all these things?’ asked Fitzherbert.

‘I keep my ears open,’ said the water vole. ‘Windsor folk come out boating on the river and I listen to all the latest gossip.’

‘She doesn’t sound very happy, this queen,’ said Fitzherbert.

‘She isn’t. Grumpy old thing, from all accounts.’

‘Perhaps she needs cheering up.’

‘Easier said than done. Anybody tries making a joke, she says, “We are not amused”,’ said the vole, and with that he vanished into his burrow.

A moment later he stuck his head out again.

‘She might be amused at you,’ he said. ‘Why don’t you pay her a visit?’

Why don’t I? thought the swoose.

‘I will,’ he said, ‘and I’ll come back and tell you all about it.’

Then it occurred to him that there were probably a great many water voles living beside the Thames.

‘So can you tell me your name, please?’ he said.

‘Alph,’ said the vole, and he disappeared once more.