CHAPTER TWO

Boyhood:A Fish Tale

1820–25

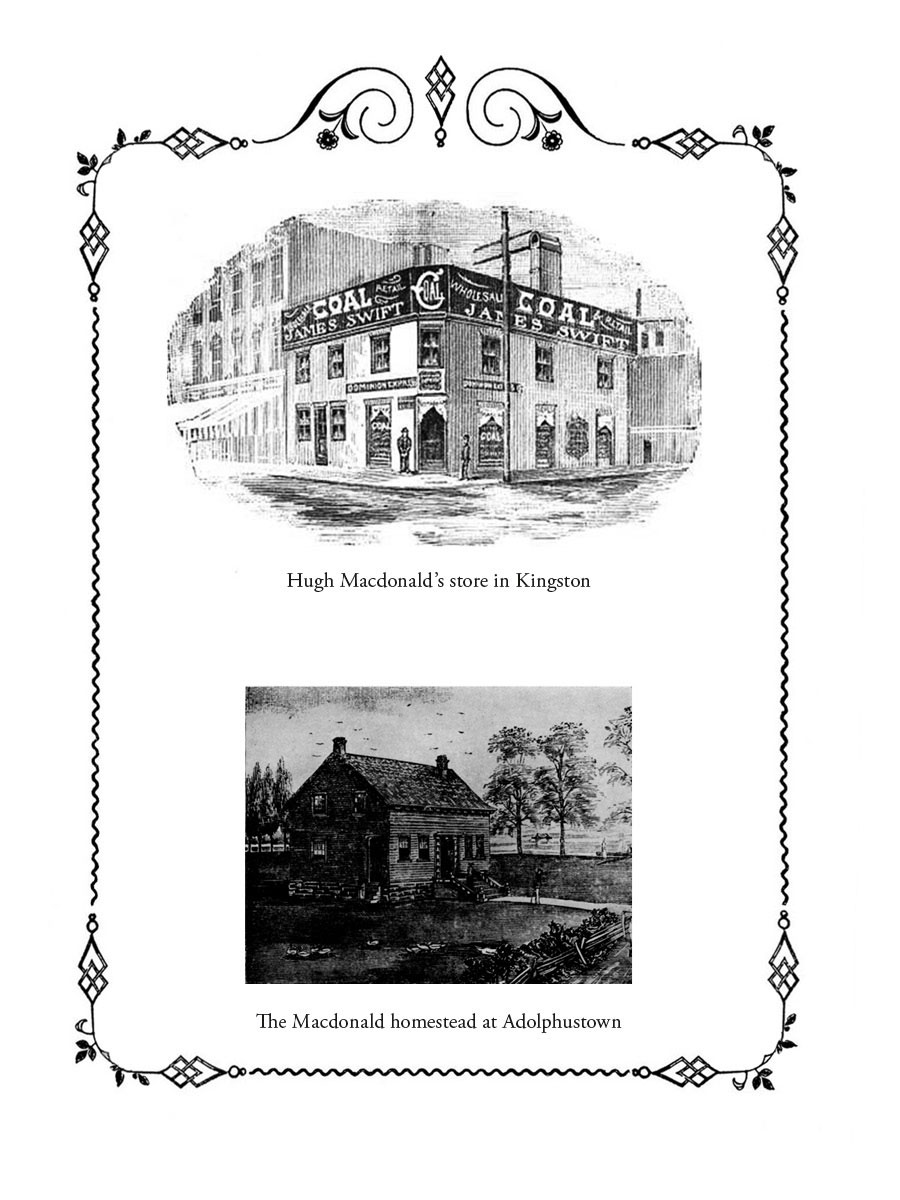

Three months after their arrival in Upper Canada, Hugh Macdonald set up a general store on King Street in Kingston, where he sold an eclectic collection of groceries, liquor, gun paraphernalia, and assorted hardware. An advertisement in the Kingston Chronicle on July 3, 1821, informed readers of new “fancy goods suitable for the season,” and went on to list commonly available stock, including “Wines, Jamaica Spirits, Brandy, Gin, Shrub and Vinegar, Powder and Shot, English Window Glass and Putty.”

Initially, the family lived above the shop and enjoyed adequate provisions from their own store. For a while, at least, their new life in Upper Canada was off to a good start.

Unfortunately, the shop failed rather quickly. Undaunted by another business fiasco, Hugh set up a new shop on Store Street (now known as Princess Street). In short order, this shop also began to flounder.

It was during this time that John A. witnessed the violent death of his younger brother James, who at five years old was brutally beaten by a drunken servant named Kennedy. The Macdonald family kept the story of James’s death a secret, and it was never talked about until many decades later when Sir John finally broke the silence. Amongst the varying accounts of what transpired, one story seems consistent. James had apparently tried to accompany his parents on an evening walk but was sent home to remain with the other children. What happened next is less clear, but it seems that the children’s caregiver, Kennedy, a secret drinker, reacted to the crying boy by either shoving him into the iron grate of a fireplace or beating him, or perhaps both. In any case, shortly after this incident James died of internal injuries. Incredibly, the family did not press charges and merely ran a short, sad obituary in the Kingston paper acknowledging the boy’s death.

Following James’s horrifying death and the failures of Hugh Macdonald’s Kingston ventures, the family decided to relocate to Hay Bay, on the Bay of Quinte, west of Kingston. By 1824, Hugh opened a shop in Hay Bay and was the local agent for the Kingston Chronicle. The family settled into their home on the banks of Lake Ontario, and the three children walked together on the daily six-mile round trip between home and school.

During the Hay Bay era, the young John A. was out one summer day, exploring the local waterfront when he ran into a man fishing from the shore. Nine-year-old John walked up, thrust out his hand, and introduced himself to the fisherman, admiring his catch and telling the man his life story. They talked for a while until the fisherman cast his line again. Just as soon as the man had turned his back on the boy and returned his attention to his work, John A. grabbed the biggest of his fish — a large black bass — and ran for home. The fisherman shouted out after him to no avail.

Years later, in 1837, when John A. was speaking at a political gathering in the Adolphustown Town Hall, Mr. Guy Casey was waiting for his opportunity. When his moment came, he rose and told the story of a young boy named John A. Macdonald who once stole his fish and ran for home. Mr. Casey then demanded that John A. publicly acknowledge his crime. The crowd turned expectantly to John A., who bowed his head solemnly and said,

Mr. Chairman and yeoman of Adolphustown, what my old neighbour has told you about the theft of his beautiful fish is absolutely true. I can recall as though it were but yesterday how frightened I was at that unearthly yell of our good friend, which almost caused me to drop the fish so as to make better speed, but I managed to hold onto it when I saw he was not chasing me. I was clean out of breath when I burst into the house and fell headlong with it on the floor, and gasped for breath as I told my father where I found it, and that there were lots more like it where this came from. I humbly beg your pardon, Guy, and my only regret is that I can’t steal another one like it here tonight and have it for breakfast in the morning. Mother said it was the best black bass she ever cooked.3

Not surprisingly, John A.’s flattery, honesty, and charm appeased Guy Casey and won over the crowd. This great fish tale, one of John A.’s early public speeches, brought the house down.

THE IMPORTANCE OF FISH AND GAME

Any inexpensive source of food was sought after, and fish and game were no exception. The early settlers initially learned to hunt and fish from the First Nations. For thousands of years, the aboriginal people had fished using spears, nets, hooks, traps and longlines and hunted with snare traps, spears, and later, with bows and arrows. They treated the animals and fish with respect and took only what they needed. Almost nothing went to waste.

The abundance of fish and game was a boon to new settlers whose principal protein source would otherwise have been salted pork — a dish that quickly grew monotonous to the palate. They began to hunt deer, moose, rabbit, hare, goose, duck, wild pigeon, wild turkey, quail, ptarmigan, partridge, and bear. Raccoon, beaver, porcupine, and even black squirrel were also sought after. As the settlers moved further west to the prairies, they depended on venison, elk, moose, bighorn sheep, lynx, rabbit, gopher, prairie hen, goose, and most importantly of all, buffalo, until the extermination of the herds, beginning in 1875. The settlers brought with them guns and ammunition, and what they didn’t hunt for themselves, they traded with the First Nations, offering in exchange flour and salted pork.

Fishing was equally important. Beginning when the first Europeans reached the east coast of North America and found the waters teeming with fish, shellfish, and seals, a new industry was born. There are stories of fish being so plentiful that one only needed to dip a net in the water in order to have food for dinner. It was not unusual for families to lay up six or eight barrels of fish to last through the winter, although ice fishing was common for those in close enough proximity to a frozen lake. Fishing was not just an industry but also a practical and productive pastime. Cod, halibut, haddock, mackerel, pollock, sardines, herring, lobsters, mussels, and oysters came from the sea coasts. Inland, the lakes and rivers supplied pike, pickerel, muskellunge, eels, whitefish, largemouth bass, mullet, lake herring, sturgeon, burbot, carp, shad, and wall-eye. Smaller fish like salmon, trout, perch, sunfish, and small mouth bass were also prevalent. Whitefish, which were abundant in Upper Canada lakes, were a universal favourite, prized for their rich, fine flavour.

The Black bass that John A. stole from Guy Casey was likely a largemouth bass, reported to grow to up to a metre (or just over three feet) in length, though it would be rare to find one of that size now.

This recipe for a baked and stuffed black bass is from The Canadian Home Cookbook, 1877. It doesn’t specify the weight of fish required, but given the amount of stuffing produced with “eight good sized onions,” a very large fish is needed. Alternately, cut the amount of stuffing in half. Whole salmon also works well as a substitute for the bass.