THE CORPORATE HISTORY PART ONE: THE FANTASTIC MR. FOX (1879-1935)

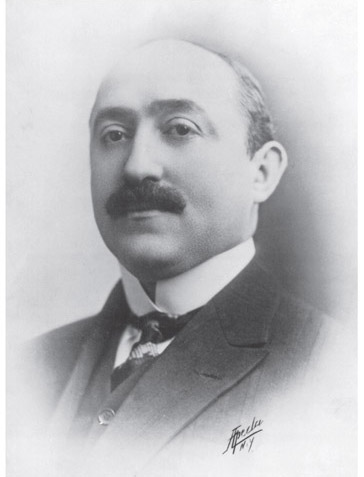

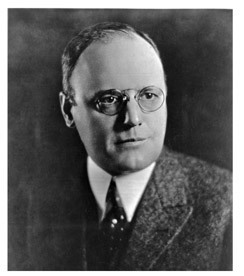

William Fox

When I entered, actively, the producing field of motion pictures I was actuated by a double motive. The so-called features that I had been selecting with all the care possible for my theatres did not fill my ideals of the highest standard possible in motion pictures. Therefore, I was fairly driven, in the interest of my patrons, and also as a secondary consideration in the belief that there was immense demand for really good pictures, into the manufacturing end of the business . . . I decided to carry out, in my motion picture–producing career, the same ideals as I had introduced at the Academy of Music. That is to say . . . that the public insistently demands photoplay features by great and world-famous authors, featuring celebrated dramatic stars . . . What concerned me . . . was to make a name that would stand for the finest in entertainment the world over.

—William Fox, founder (1915 press release)

The drive for success that transformed William Fox into the Hollywood mogul who forged the foundations for Twentieth Century Fox was evident to his father, Michael Fuchs, a Jewish émigré from Tulcheva, Hungary, and mother Anna (Fried) from an early age. In fact by the age of eleven young William, the eldest of thirteen raised in bitter poverty in the Lower East Side immigrant ghettos of New York, was the main family breadwinner.

He left the Sheriff Street public school to work twelve hours a day as a coat liner at D. Cohen & Sons, a garment center sweatshop. One day, riding to work in an ice wagon, he fell out and broke his left arm in three places. His parents did not have the money for a specialist, and the elbow never healed correctly. If William Fox the child was determined to succeed, William Fox the man, left with an infirmity for the rest of his life, was even more tenacious.

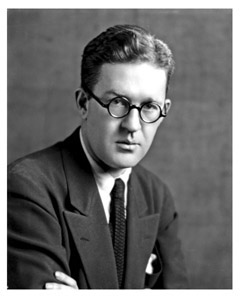

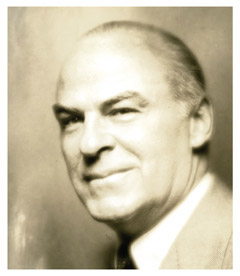

F. W. Murnau

Working his way up at G. Lippman & Sons—he was foreman at thirteen—granted him the financial security to marry Eve Leo, the daughter of a clothing manufacturer, on New Year’s Eve 1899 at twenty. They had two daughters, Caroline and Isabelle. Fox soon opened his first business, the Knickerbocker Cloth Examining and Shrinking Company, and by the time he sold out in 1904, he had earned a profit of $50,000.

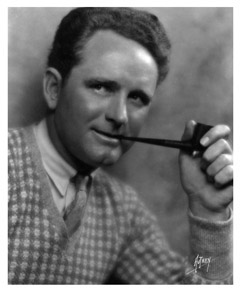

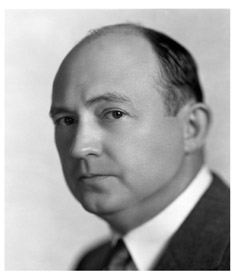

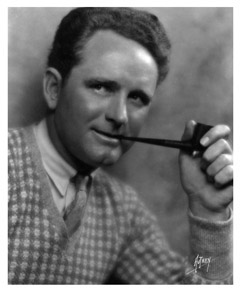

John Ford

By then show business was pulling him away from the thriving garment industry sweatshops. To earn extra income as a child Fox had performed a comedy routine in vaudeville and he’d always been intrigued by how such places were managed. An even greater allure was the magic of nickelodeons, which presented motion pictures for a nickel. Convincing two partners to join him, Fox purchased a Brooklyn nickelodeon at 200 Broadway, and then another, until they had fifteen of them. This allowed him to purchase his first large theater—the Gaiety—at 194 Grand Street, Brooklyn. He renamed it “The Comedy Theatre.” By 1908, from an office at 24 Union Square, William Fox was offering the potent combination of vaudeville and movies in Manhattan and Brooklyn, all the while distributing films to other theaters through his own Greater New York Film Rental Company. Two years later he leased the prestigious New York Academy of Music building, at 14th Street and Irving Place in Manhattan, that became the William Fox Theatre and hosted the Prince of Wales in 1921.

Frank Borzage

His menu for success was to make entertainment affordable for everyone by offering “popular prices,” and by polling his audiences to discover what it was they wanted, he made a fascinating discovery: “I sent out 10,000 cards requesting patrons to say what part of the performance they liked best,” he told a journalist in 1912. “Fifty-five percent of the answers were in favor of moving pictures . . . more than the vaudeville acts. The only explanation I can find is that motion pictures, perhaps, realize the American idea of speed and activity.”

No two words better describe William Fox’s meteoric rise in the burgeoning entertainment industry. Nothing was going to stop him—not even an American legend like Thomas Alva Edison. After inventing the technology that made movies possible, Edison and the reigning motion picture studios of the time formed the Motion Picture Patents Company, virtually monopolizing the production of movies. Their General Film Company similarly attempted to monopolize distribution. When they offered to buy Fox’s Greater New York Film Rental Company for $75,000, Fox impudently countered with $750,000. When they deprived him of access to their films, he sued under the newly enacted Sherman Antitrust Act, and won.

This pioneering fight with future moguls Adolph Zukor (Paramount) and Carl Laemmle (Universal) ended Edison’s monopoly and allowed Fox the freedom to interlock production distribution and exhibition, thereby giving birth to the Hollywood studio system.

Fox wasted no time in expanding the distribution of films from his new offices at 116 East Street, including contracting out all the films produced by the Balboa Amusement Producing Company in Long Beach, California. Then he was ready to form his own company, introducing Box Office Attractions, Inc., in 1914, headquartered at the recently purchased Éclair studio in Fort Lee, New Jersey. From there he introduced his very first movie—an orphan’s tale called Life’s Shop Window on November 19, 1914, directed by J. Gordon Edwards and starring Claire Whitney.

The Fox Film Corporation was born on February 1, 1915, absorbing Box Office Attractions, Inc. From its first headquarters in the Leavitt Building at 130 West Forty-Sixth Street, Fox oversaw films like director Raoul Walsh’s Regeneration (1915), the first feature-length gangster film. The most important men in his growing ranks were Winfield R. Sheehan and Sol M. Wurtzel. Wurtzel was his private secretary, involved in all aspects of production, and Sheehan—a power in New York journalism and politics—became general manager, building up the company’s star roster, film production, and network of domestic and European distribution.

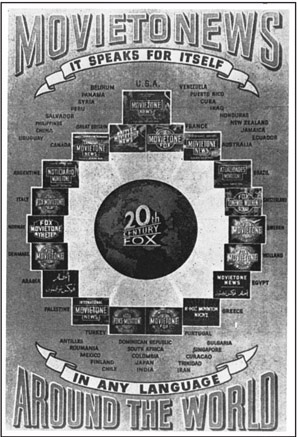

The Fox Movietonews cameramen traveled the world capturing current events on film from the 1920s through the 1960s. It was the biggest and best newsreel outfit producing more newsreel footage than any of its competitors.

Creating their first constellation of stars required pioneering methods of advertising and marketing. Theodosia Goodman was their greatest success, debuting as “Miss Theda Bara” in A Fool There Was (1915). She was the first publicity-made star and sex symbol on the American screen, popularizing the seductive—and destructive—“vamp,” making thirty-nine additional films in four years. Although Fox publicists insisted her name was created from an anagram for “Arab Death,” it was in fact the name of her maternal Swiss grandfather, Francis Bara de Coppet.

Witnessing her popularity, Fox soon cast Valeska Surratt, Virginia Pearson, and Betty Blythe to follow Bara’s lead. The company’s first athlete-turned-movie-star was former champion long-distance swimmer, Annette Kellerman, who starred in the company’s first million-dollar production, A Daughter of the Gods (1916). The enormously popular William Farnum appeared in the studio’s first adaptations of Les Miserables (1918) and Riders of the Purple Sage (1918). Farnum’s brother Dustin also starred in numerous Fox films until 1924, a year longer than his brother. Raoul Walsh’s brother George and wife Miriam Cooper were also among the company’s earliest stars.

To make his films William Fox utilized a variety of studios on the East Coast between 1915 and 1919, including nine in New Jersey, four in Manhattan, Scott’s Farm on Staten Island, and others in Brooklyn, the Bronx, and Yonkers. He established others in Miami, Florida, and Kingston, Jamaica, and leased the former Colonel William N. Selig Studios in the Los Angeles, California, suburb of Edendale, across the street from the Max Sennett Studios in 1915. While visiting his new acquisition the following year—and deeming it too small for his needs—he met and signed Selig’s Tom Mix, the first cowboy movie star, and acquired five and a half acres of land on the southwest corner of Sunset Boulevard and Western Avenue in Hollywood. He then purchased an additional eight acres across the street to start a new studio. Sol Wurtzel was promoted and dispatched to run what became known as the Western Avenue Studio in 1917.

Movietone City officially opens on October 28, 1928, with 30 buildings at a cost of more than $12 million.

In 1918 Fox and Sheehan developed the company’s first series of studio brands for their films to help develop stars, including Standard (the highest quality, often historical films), Victory (the second tier, often action films), Excel (for new talent), and Sunshine (for comedies). The following year Sheehan opened offices overseas for film distribution, talent scouting, and the realization of another Fox dream: a division for the making of Fox newsreels. They quickly became the best in the business, with cameramen sent literally around the world to supply theaters with footage of current events.

Squeezed out of the Leavitt Building, the pair supervised construction of a three-floor studio to centralize their far-flung holdings in 1919. At a cost of $2.5 million, it was the largest yet built in the world under one roof, an imposing brick building that filled a square block between Fifty-Fifth and Fifty-Sixth Streets along Tenth Avenue in Manhattan.

From the main entrance the corporate offices—including the sales, distribution, advertising, and accounting departments—were accessed on the first and second floors. The film lab was split between the two floors, along with twelve screening rooms. The grandest of these screening rooms was on the second floor with the wardrobe and art departments, set construction, dressing rooms, and the commissary. The third floor accommodated twenty silent-film companies and star dressing rooms. The building later housed both Fox News and Hearst Metrotone News. Fox also leased the old Kelly-Springfield tire factory one block south on Tenth Avenue and Fifty-Fourth Street, for more room, including space for the East Coast story department and paint and sign shop.

Edward R. Tinker

In 1920 Fox celebrated his success with the purchase of an estate at Woodmere, Long Island, where he could rule his family, too. Many of his family members were involved within the corporation. While his wife Eve helped to select scripts, supervise some of the productions, and design Fox theaters, her brothers Jack and Joe ran domestic distribution of the films and Fox Theatres, respectively, and her brother Aaron headed the film lab.

Sidney Kent

In 1923, with the Western Avenue Studio bursting at the seams, William Fox expanded his southern California land holdings by purchasing 99.34 acres of low rolling hills to the west of the small community of Beverly Hills, from the Janss family. Industry insiders mocked him for making this trek into the wilderness and giving Winfield Sheehan $2 million to transform it into Fox Hills, “the Greatest Outdoor Studio.”

Harley Clarke

As part of an industry trend, Fox was slowly phasing out moviemaking on the East Coast. Such prestigious efforts as Emmett Flynn’s East Lynne (1925) and Raoul Walsh’s World War I epic, What Price Glory (1926), were now coming out of California. Glory made stars of Edmund Lowe and Victor McLaglen, who reprised their roles in films like The Cock-Eyed World (1929), Women of All Nations (1931), and Hot Pepper (1933).

By 1926 Fox had Sheehan as senior studio executive, with Sol Wurtzel second in command of eleven production teams. His demand that they upgrade the quality of their directors and stars ushered in the studio’s first golden age of filmmaking. There were three star directors: Frank Borzage, F. W. Murnau, and John Ford. After directing half a dozen films for the studio, Borzage, known as Hollywood’s great romanticist, made 7th Heaven (1927), which became a major success, launching the careers of wholesome Charles Farrell and Janet Gaynor, the most popular romantic team of the silent and early sound era.

F. W. Murnau’s Sunrise: A Song of Two Humans (1928) is regarded as the greatest silent film ever made. Remarkably, Janet Gaynor starred in this milestone, as well, opposite George O’Brien. Sunrise earned rave critical reviews, but was not a hit at the box office. Winfield Sheehan’s interference to correct this “fault” in Murnau’s subsequent films, 4 Devils (1929 and City Girl (1929), caused the director to leave the studio—but not before profoundly affecting the way Fox films were made.

Among Murnau’s greatest admirers was John Ford. Combining Borzage’s sentiment with Murnau’s art, Ford’s silent-film work presages his great work to come. From his first effort, Just Pals (1920), starring Buck Jones, came a distinguished line of films about worthy but often unassuming or misunderstood men, including Doctor Bull (1933), Judge Priest (1934), Steamboat Round the Bend (1935), The Prisoner of Shark Island (1936), and Young Mr. Lincoln (1939). From the epic The Iron Horse (1925) came Drums Along the Mohawk (1939) and My Darling Clementine (1946). From family dramas like Four Sons (1928) came Pilgrimage (1933), The Grapes of Wrath (1940), and How Green Was My Valley (1941).

William Fox leapt ahead of competing studios that were unsure about “talking pictures” by forming the Fox-Case Corporation with inventor Theodore Case, to perfect sound on film. His was the only Hollywood studio maintaining its own research facilities for such a purpose. The result, patented as Movietone, became the industry standard.

He kept his newsreel at the forefront, too, by adding sound to them first beginning in the spring of 1927. By the fall of 1928, $10 million had been spent to transform Fox Hills into Movietone City, the first studio built solely for sound pictures in Southern California. On October 28, Winnie Sheehan presided at the official opening, and Fox was present via a special wire hookup to New York.

Movietone City was so named because the plant—the majority of which was built between 1928 and 1932—was indeed laid out like one. There was a “factory” area comprised of unique and grand Assyrian/Mesopotamian-looking soundstages and Spanish Colonial Revival offices, and there was a quiet “residential” area made up of service buildings and bungalows in Period Revival and other styles for directors, actors, and writers.

By the end of the year the new studio had released John Ford’s Four Sons (1928), Frank Borzage’s Street Angel (1928), and Raoul Walsh’s The Red Dance (1928), all box office winners. The company was now second only to Loews Incorporated, parent company of Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer.

For its fifteenth anniversary the company introduced a milestone motion picture featuring dazzling new technology, and scored the coup of signing the most beloved man in America to a contract. With its unique state-of-the-art newsreel field equipment, only Fox could have made In Old Arizona (1929), the first all-talking feature made outdoors. Its star, Warner Baxter, earned an Academy Award and a long career at the studio.

The technological leap was introducing 70mm film as “Fox Grandeur” with the Fox Movietone Follies of 1929, in fifty-fifty partnership with financier Harley Clarke, president of General Theaters Equipment. And it was Winnie Sheehan who proudly signed Will Rogers to a studio contract. Rogers made his debut at the studio in his first “talkie” (he dubbed them “noisies”), They Had to See Paris (1929). His films continued to be welcome box-office hits. Commenting on Hollywood in that era, he reported: “Everybody that can’t sing has a double that can, and everybody that can’t talk is going right on and proving it. Everyone is so busy enunciating that they pay no attention to what they are saying.”

Cavalcade (1933) became Fox’s first Best Picture winner due to the contributions of (left to right) stars Clive Brook and Diana Wynyard, producer Winfield Sheehan, and director Frank Lloyd.

Back in 1925 William Fox had formed the Fox Theatres Corporation to strengthen his company’s exhibition arm and to compete with Adolph Zukor’s Paramount, which led the industry with the greatest number of theaters. By 1929 Fox had surpassed Zukor, with a network of over 1,500 theaters including the prestigious Fox Metropolitan Playhouses Inc. circuit, encompassing the four largest boroughs of New York; the Roxy circuit, including the Roxy Theatre—the largest in the world—in Manhattan; the Wesco theaters in California; Fox Midwesco in Illinois and Wisconsin; the New England Poli theater chain; and interests in Gaumont–British Picture Corporation Ltd. in England.

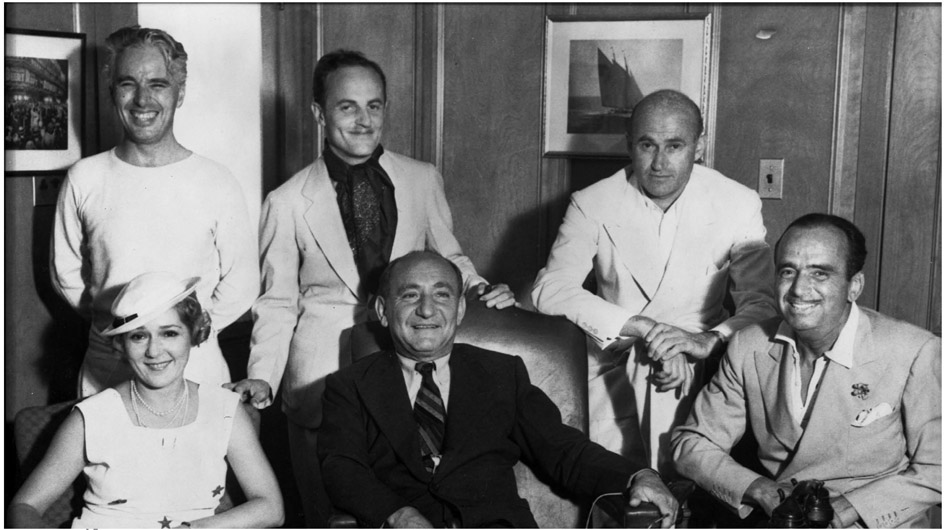

The fledgling Twentieth Century Pictures got a big boost by teaming up with the luminaries at United Artists in 1933. Back Row (left to right): Charlie Chaplin, Darryl Zanuck, Samuel Goldwyn. Front row: Mary Pickford, Joseph Schenck, Douglas Fairbanks.

As the largest movie theater owner in New York, Fox turned offices in the Roxy into his world headquarters. By the spring of 1929 he owned the controlling share of prestigious Loews Incorporated, with its own theater chain and MGM. Estimated at a value of $300 million, the fiftyone-year-old mogul’s empire was at its height. In his biography of Fox, Upton Sinclair reeled at his success and grand-scale ambition, noting that he “planned to get all the moving picture theatres in the United States under his control sooner or later . . . I think also that he planned to have the making of moving pictures entirely in his own hands.”

Then fate, for once, took a dramatic turn against William Fox. As MGM mogul Louis B. Mayer sought to break the Loews deal by appealing to President Hoover and his antitrust division of the Justice Department, Fox was involved in a serious automobile accident on July 17, 1929. He was headed to a golf match at the Lakeview Country Club on Long Island, in an effort to strengthen his ties with Loews New York man Nick Schenck, when his chauffeur got lost and was hit by another car that sent them careening into a ditch on Old Westbury Road. The chauffeur was killed, and it took Fox three months to recover from his injuries. Five days after his return to his office, the stock market crash struck another lethal blow to his company. When bankers demanded payment for the money he’d borrowed to build his empire, Fox was unable to comply.

Whether due to L. B. Mayer’s efforts or not, on November 27, 1929, the US attorney general filed an antitrust suit, and William Fox’s situation worsened. A few days later, on December 3, he got a loan by forming a five-year trusteeship co-administered by Halsey, Stuart, & Co. and John Otterson of the American Telephone and Telegraph Company (AT&T), with whom he had partnered for the development of sound motion pictures. He put his controlling shares in Fox Film and Fox Theaters up for collateral.

Finding the partnership unsupportive, Fox sought refinancing elsewhere. The resulting litigation upheld the original trust that wanted him out and the company in receivership. Even Winfield Sheehan aligned himself against him. There was no one to help him from defaulting on his interest payments, and on April 1, 1930, he finally admitted defeat. He sold his controlling shares for $15 million to Harley L. Clarke and General Theaters Equipment, Inc., on April 6, and could only serve as a director and chairman of an advisory board to help put it back on a sound financial basis. This he accomplished in five years. The Loews merger collapsed after less than a year, and Fox Grandeur proved to be a short-lived luxury exhibitors could not afford during the Depression.

Management of Fox Film passed to Harley Clarke, and box-office profits plummeted from the $9.5 million of William Fox’s last year in 1930, to a loss of more than $4 million in 1931. Edward R. Tinker, board chairman of Chase National, replaced Clarke in November. By 1932, when the Depression had dragged most of the Hollywood studios down into the red, Fox was at the bottom. Tinker brought in Paramount sales chief Sidney R. Kent to take his job when he retired. Kent in turn hired his brother-in-law, Paramount’s head of production, Jesse L. Lasky. A further boost came when Charles Skouras, along with younger brothers Spyros and George, stepped in to restore the Fox West Coast theater chain as the National Theaters Corporation when it toppled into bankruptcy in February of 1933.

William Fox’s Hollywood studios remained a problem. All the creative excitement he had generated by developing a team of quality studio technicians and stars in the 1920s faded. His strong leadership skills were also missed. Hit hard by the stock market crash and the stress of running a studio for a rudderless company, Winfield Sheehan became seriously ill in 1930. His famed energetic management abilities never returned. Sol Wurtzel fared no better amid the company’s wretched state.

Their decentralized producer system failed partly because Sheehan did not get along with the new ones, including Jesse Lasky and Broadway imports Buddy DeSylva and George White. Lasky’s quality films added class when the company needed it, but when they were successful, it was abroad, not at home. Disastrously, the lots began to depopulate.

Raoul Walsh left after making one of Laurence Olivier’s earliest Hollywood films (The Yellow Ticket, 1931). Frank Borzage turned down the opportunity to direct Sheehan’s next big project, Cavalcade, to move to Paramount and direct A Farewell to Arms (1932).

Those who chose to stay included Frank Lloyd, who took up Cavalcade. It was Edward Tinker’s wife who purchased the screen rights to Noel Coward’s enormously successful play and songs. Winfield Sheehan broadened its scope and box office by bringing the story up to the present day, offering a hopeful ending to a country shattered by the Depression. Released in 1933—a milestone year for the company, with The Power and the Glory, Berkeley Square, and State Fair, the first Fox film to open at Radio City Music Hall—Cavalcade earned the company its first Best Picture Academy Award.

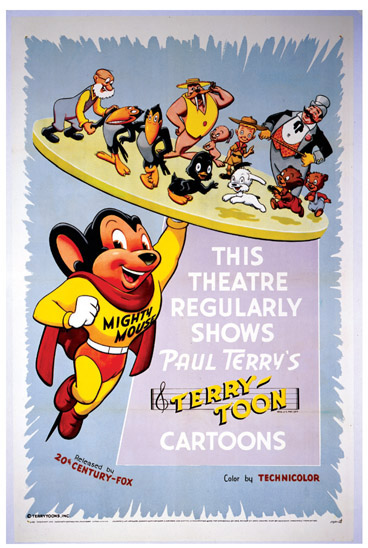

The enormous success of the Disney movies made every studio interested in animation. Fox got in the game by distributing Terrytoons.

Sheehan also picked up distribution of Earle W. Hammons’s Educational Pictures that year, which included Paul Terry’s pioneering Terrytoons. When Educational Pictures folded in 1938, Fox continued to release Terrytoons until 1968. In all, Paul Terry would produce more than 1,100 cartoons featuring such popular characters as Mighty Mouse and Heckle and Jeckle from a converted Knights of Columbus hall in New Rochelle, New York.

Although Sidney Kent had great hopes for Fritz Lang’s Liliom when it premiered in Paris in April of 1934, it remains only a sparkling remnant of his dream for Fox studios in France, Britain, and Germany, headed by producer (and brother-in-law) Robert T. Kane.

Fortunately there was that amazing five-year-old who auditioned at Movietone City that winter. She made her studio debut in Carolina (1934) with Janet Gaynor, followed by the star-making Stand Up and Cheer! (1934) and Baby Take a Bow (1934). Coached by her mother to “Sparkle!,” her ebullience and good cheer charmed everyone on the lot, and then the world. The legendary career of Shirley Temple had begun.

The timing was not lost on Winfield Sheehan. Not only did he desperately need more stars, but he needed ones that were appropriate for a new Hollywood. The Motion Picture Producers and Distributors of America (MPPA), formed in 1922, had tightened their regulation of the Motion Picture Production Code because of public outcry over the increasingly tasteless material issuing from Hollywood. Family films and child stars were in.

In this, Sheehan was also fortunate to gain another extraordinary tot named Jane Withers, who rocketed to fame playing Temple’s nemesis with delightful relish in Sol Wurtzel’s Bright Eyes (1934). Temple’s now-iconic rendition of “On the Good Ship Lollipop” sold four hundred thousand copies of sheet music and hit number three on the charts.

All this was not enough to stave off threats of foreclosure from the studio’s creditors. While he looked for a new production executive, Sidney Kent held merger discussions with MGM and Warner Bros.

Meanwhile, at the United Artists studio, Nicholas Schenck’s brother Joseph and a thirty-two-year-old producer named Darryl F. Zanuck were releasing a steady line of quality hit films under the banner of Twentieth Century Pictures. After a mere seven months, the company was among the most profitable in Hollywood. Both men had stellar reputations. Joseph had risen to chairman of the board of United Artists, and Zanuck had been head of production at Warner Bros., encouraging the studio’s pioneering efforts with sound and establishing its rich tradition for gangster films, musicals, and social-conscience pictures.

Schenck and Zanuck had received a $100,000 check of support from MGM’s Louis B. Mayer, with the proviso that Mayer’s son-in-law, William E. Goetz, became Zanuck’s executive assistant. The tie with Hollywood’s greatest studio gave the fledgling company the enviable boost of access to their stars. It was another assistant named Samuel Engel who came up with the name “Twentieth Century Pictures, Inc.” Landscape painter and matte artist Emil Kosa Jr. devised the logo, and Alfred Newman composed the fanfare.

Intrigued, Sidney Kent met with Joseph Schenck for lunch at the Grill of the Plaza Hotel in Manhattan in the spring of 1935. He offered to purchase Twentieth Century Pictures. When Schenck declined, Kent agreed to a merger. The deal was closed on May 23, and signed on May 28. Kent wanted to call the company Fox-Twentieth Century. Schenck wanted to call it the Twentieth Century Fox Film Corporation, and so it was officially named, on July 19.

Fighting the merger with a lawsuit to no avail were William and Eve Fox, who contended that Fox stockholders were being shortchanged. Weakened by a stroke, Fox died at Doctors Hospital in New York on May 8, 1952, having never returned to the industry. His funeral was held at Temple Emanu-El, on Fifth Avenue.

The trade ad placed in Variety that week by Twentieth Century Fox read in part: “His daring, initiative, and courage enabled him to make a significant contribution to the growth and development of the motion picture industry. From the beginnings of his career he engaged in the production of films of magnitude and scope, and blazed a trail for the industry in providing box-office attractions of wide popular appeal. He was truly a pioneer in foreseeing the present status of the screen as a medium of popular entertainment.”