There is no fence nor hedge ’round time that is gone. You can go back and have what you like of it if you can remember. So I can close my eyes on my valley as it is today and it is gone, and I see it as it was when I was a boy . . .

—Introduction to How Green Was My Valley (1941), screenplay by Nunnally Johnson

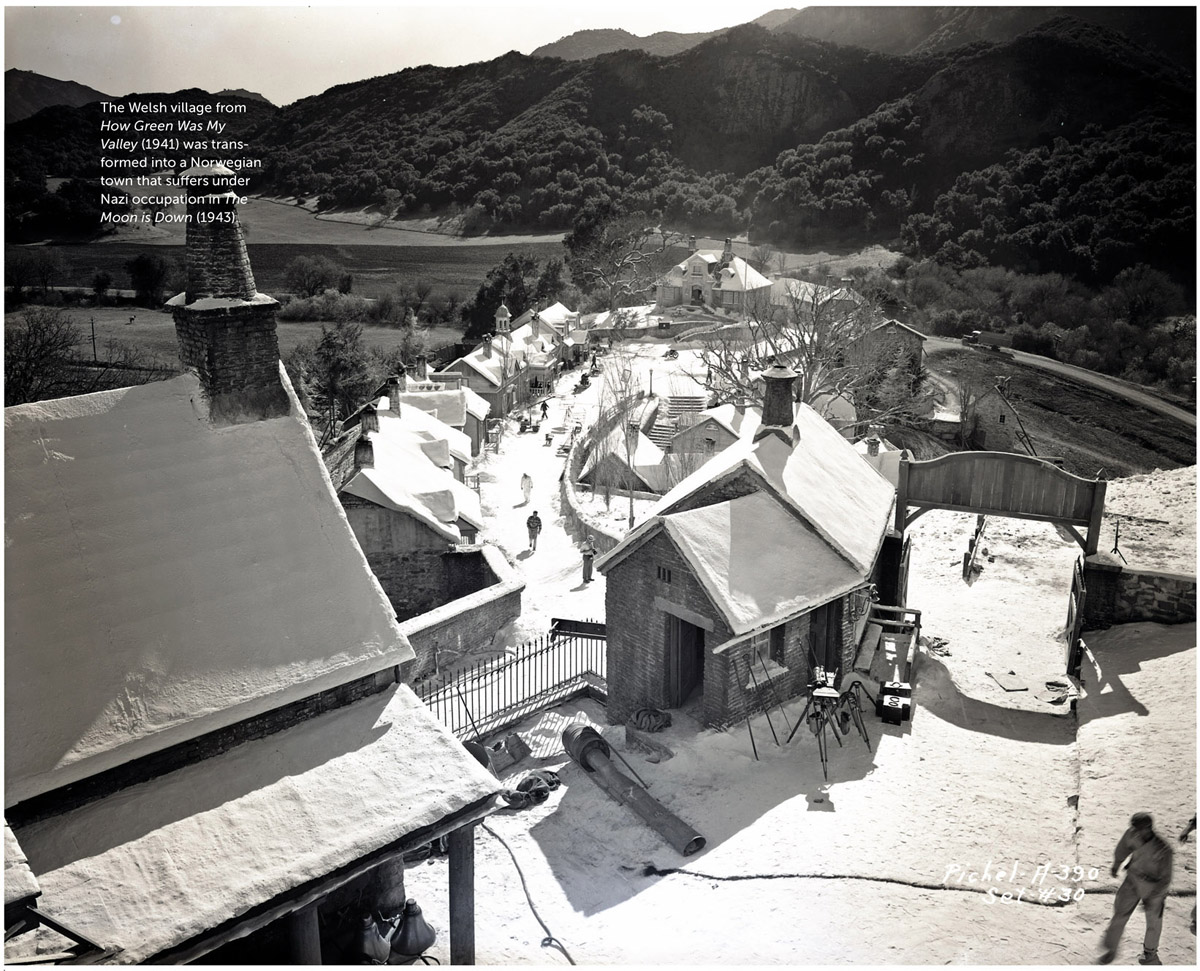

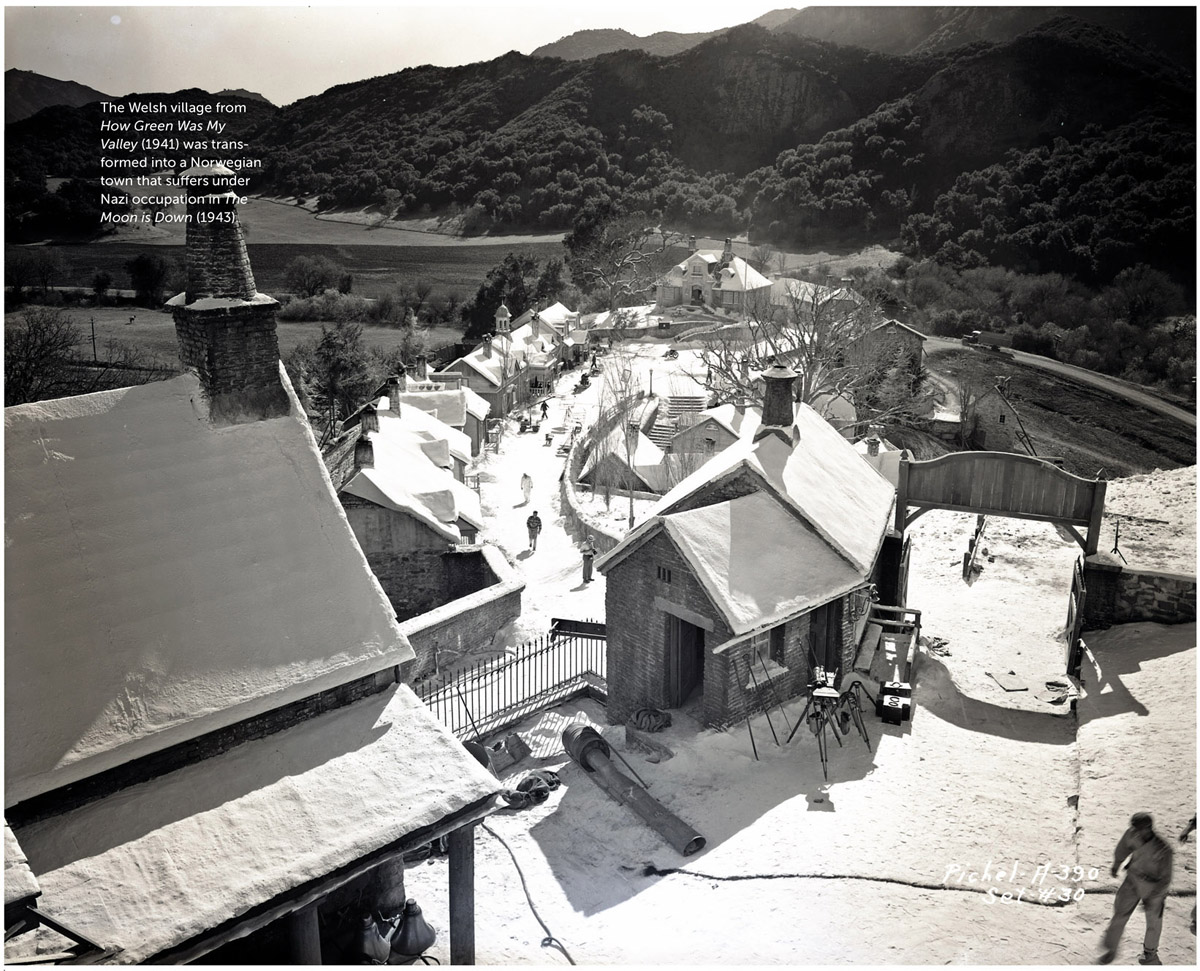

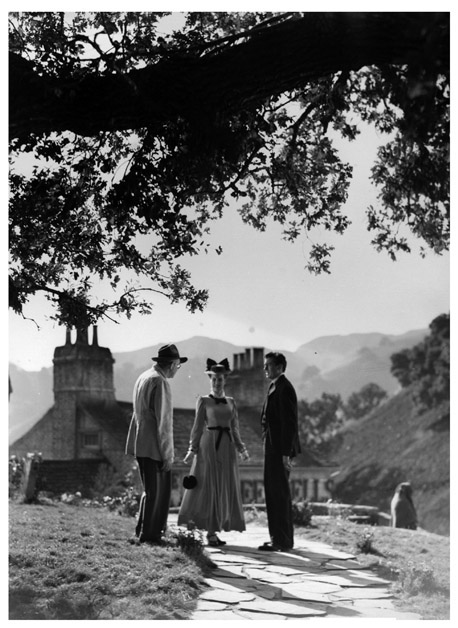

Thirty miles from the urban sprawl of Los Angeles that surrounds the Westwood studio, off Highway 101 at the Las Virgenes Road exit, are 2,403 historic acres recognizable around the world, thanks to Darryl Zanuck’s Twentieth Century Fox. At first, it was known as the “Brent’s Crag Location,” named for one of the property’s most prominent geographical features, in the early years when it was used for Chicken Wagon Family (1939), Brigham Young (1940), The Mark of Zorro (1940), and Belle Star (1941). The production of How Green Was My Valley (1941) forever immortalized these Malibu hills when Richard Day designed that impressive eighty-acre Welsh village and coal mining set.

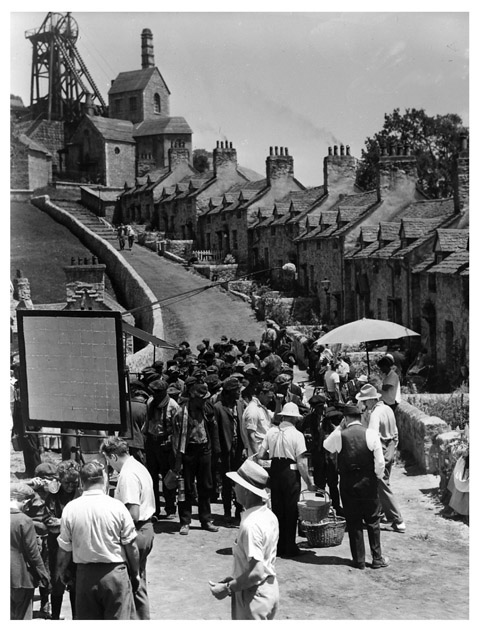

That it was made there was a unique twist of fate when World War II, and a board of directors that doubted its box office potential, nixed Darryl Zanuck’s grand plans for a Technicolor epic made on location in Wales. John Ford wanted to blacken the hillside with coal, but wartime shortages preempted that, so twenty thousand gallons of black paint had to suffice. Zanuck purchased the property, officially dubbing it the Century Ranch in 1945. The village would appear again as Norway in The Moon Is Down (1943)—another ambitious filmization of a John Steinbeck work—and then as part of the mission in remotest China for The Left Hand of God (1955).

Map of the ranch

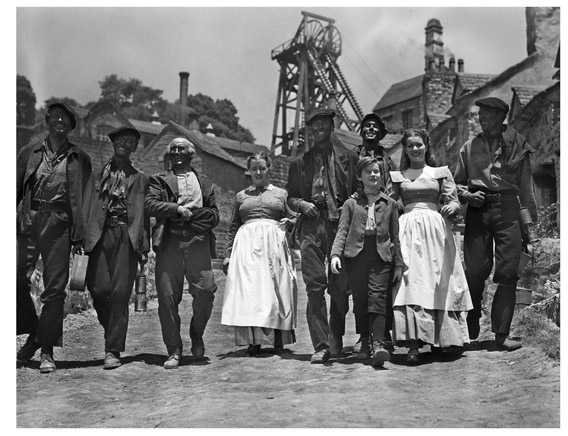

The set of the Welsh village in How Green Was My Valley (1941).

John Ford gives directions to Maureen O’Hara and Walter Pidgeon in How Green Was My Valley (1941).

Tierney would remember costar Humphrey Bogart as particularly sympathetic toward her as she began her struggle with mental illness. “I was admitted to three different hospitals—sanitariums, if you prefer—over a period of six years,” she said. “So there is hope for everybody.”

Witnessing filmmaking at the Ranch at its height in the 1950s was Richard Todd, who Zanuck considered key to the success of A Man Called Peter (1955), The Virgin Queen (1955), and D-Day the Sixth of June (1956).

“The studios were vast in comparison with their counterparts in Europe,” he recalled. “At the Fox Ranch there were wood-and-plaster fortresses, stockades, mining townships and ranch buildings used again and again in Westerns, an Indian village left over from a Tyrone Power film, a Mexican village, and what looked to me like part of a medieval English hamlet. California’s climate made it possible for these flimsy structures to remain intact for years, something that would have been impossible in Europe.”

The cast of How Green Was My Valley (1941).

Zanuck was equally impressed with the Dublin-born matinee idol’s heroic service during World War II, and asked him to play himself and re-enact his active part in D-Day, as Captain in the Parachute Regiment (the 6th Airborne) for The Longest Day (1962). Instead Todd chose to play Major John Howard who speaks to an officer of the Parachute Regiment that would have been young Captain Todd himself.

Gene Tierney and Humphrey Bogart are filmed as they stroll along the ranch which doubled for China in The Left Hand of God (1955).

That ranch or farmhouse set is the one where Cary Grant proposes to Jeanne Crain in the richly comic People Will Talk (1951), and where June Haver and Natalie Wood lived in Scudda Hoo! Scudda Hay! (1948). That film brought Marilyn Monroe out here for a sequence at Century Lake, all seven acres of it dammed up from Malibu Creek by wealthy businessmen at the turn of the twentieth century as part of Crags Country Club. Marilyn was back during her romance with Elia Kazan while he directed Viva Zapata! (1952).

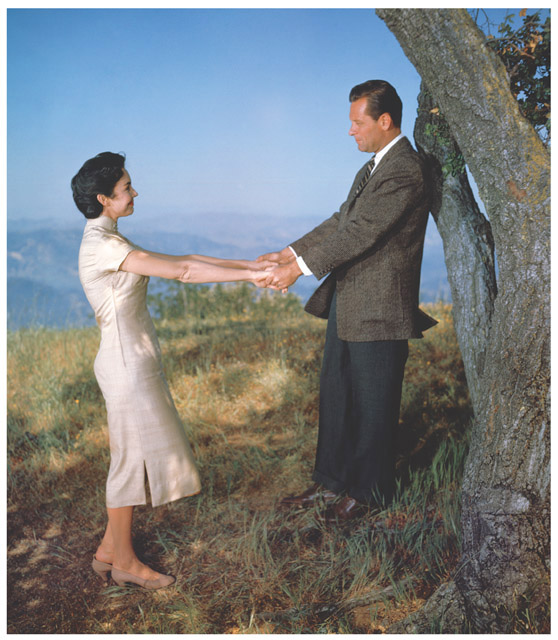

That “high and windy hill” was actually in the Santa Monica mountains, not Hong Kong even though many of the on-location shots were made there for Love is a Many-Splendored Thing (1955) starring William Holden and Jennifer Jones.

The farmhouse set became the home of the doomed Booths for Prince of Players (1955), the Amish for Violent Saturday (1955), and Elvis Presley in Love Me Tender (1956). He also made Flaming Star (1960) and Wild in the Country (1961) out here when he was arguably the most famous entertainer in the world. Not famous enough, however, to access the telephone. While making these movies he discovered to his dismay that the ranch had only one phone, and that was at the Torpin home, the caretakers of the property, who were distantly related to the Zanucks. When he showed up there, Mrs. Torpin would not let the star, with his muddy boots, into the house.

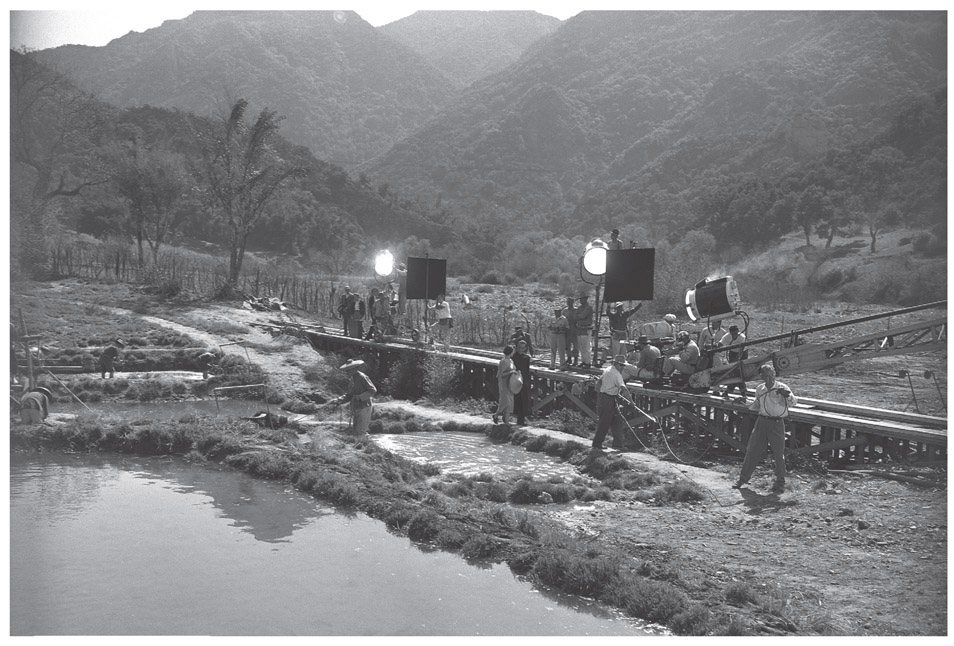

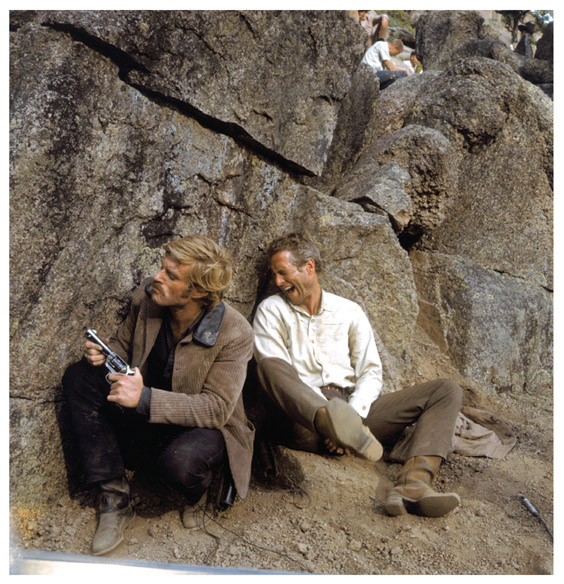

For the next fifteen years that remarkable topography of rising cliffs and canyons would substitute for China again, both for the legendary love scene “high on a windy hill” between William Holden and Jennifer Jones, for Love is a Many-Splendored Thing (1955), and as the site of the China Light mission, where seaman Steve McQueen reunites with teacher Candice Bergen in The Sand Pebbles (1966). It provided a fantastic setting for Arthur P. Jacobs’s Doctor Dolittle (1967) and Planet of the Apes (1968), and for Paul Newman and Robert Redford’s memorable jump in Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (1969).

But what brings most fans to the area is the fact that it served as Korea—due to budgetary reasons, Richard Zanuck insisted—for the film and television show based on Dr. H. Richard Hornberger’s novel, MASH: A Novel About Three Army Doctors. It was Ingo Preminger, brother of Otto, who proposed making the film that Robert Aldrich turned into a classic. The TV version, using the still-standing sets, was pitched successfully to CBS. Gene Reynolds, whose career at Fox stretched from his child-star days in In Old Chicago (1938) to directing Room 222, supervised production.

The ranch became the location for Elvis Presley’s first film, Love Me Tender (1956). Debra Paget sits in the wagon with Elvis and Richard Egan is on the horse on the right.

Batman (Adam West) drives the Batboat in this scene from the Batman (1966) movie, which was filmed in the tank on the ranch.

This scene with Robert Redford, left, and Paul Newman from Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (1969) was filmed in Utah, but the long shot of the jump that followed was filmed at the ranch.

After the Westwood backlot was razed some sets were moved here, including railroad cars, and a water tank was built for filming Cleopatra’s (1963) miniatures. It became the second [Fred] Sersen Lake featuring sloped sides that allowed trucks to access the bottom for set placement. The tank held three million gallons, with a sump behind the backing capable of storing four million gallons. The pump could fill the lake in one hour and forty minutes, and it could be drained back into the sump in fifty minutes. The front of the tank was 198 feet wide. The backing faced south, toward the sun, and was 366 feet wide and 85 feet high. The top tilted away 14 degrees from the bottom to the top to better catch the sunlight. Over this a heavy canvas that could be painted was nailed to the plywood. The tank was also used for Batman (1966), and emptied to hold models and the forty-foot-high mock-up for stunt people for The Towering Inferno (1974).

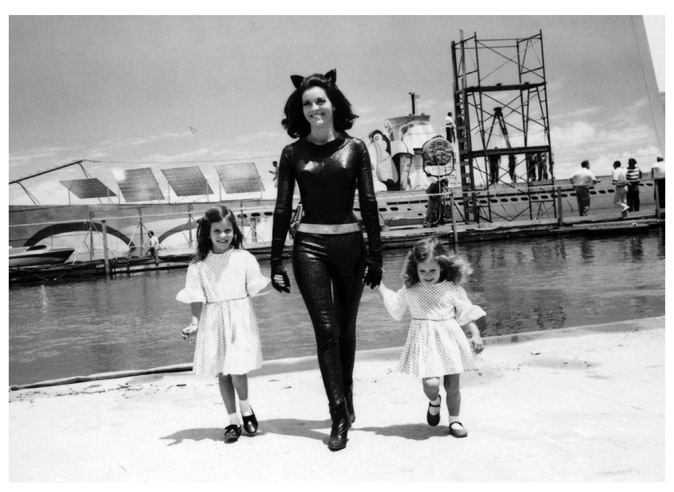

Lee Meriwether as Catwoman and her daughters in front of the tank used in Batman (1966).

The ape village for Planet of the Apes (1968) was built at the ranch.

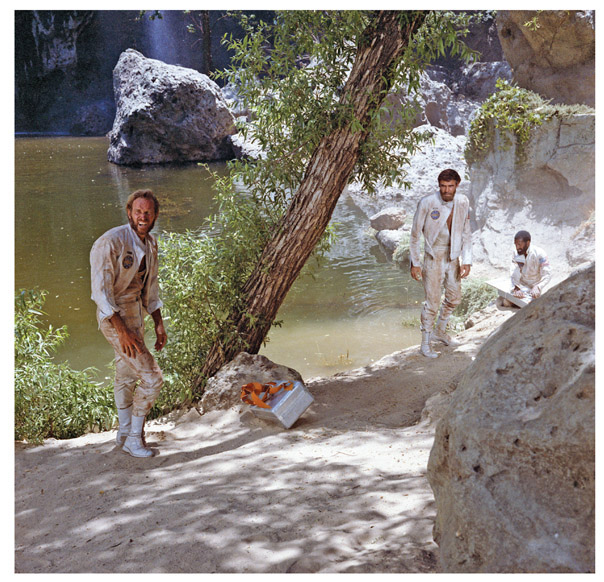

Other scenes from Planet of the Apes (1968) were also shot on the ranch including at the rock pool where the astronauts swim. (L-R) Charlton Heston, Robert Gunner, and Jeff Burton.

Things get a bit tense in the ape village built on the ranch.

Although merger plans in May of 1963 between Darryl Zanuck, Columbia president A. Schneider, and MGM chief Robert H. O’Brien, including the construction of a “Malibu Studio,” proved prohibitively expensive the company did purchase 236 acres from soon-to-be-governor Ronald Reagan in December of 1966. They paid $1.9 million for this land, adjacent to the Ranch, and signed a six-year option to buy Reagan’s remaining fifty-four acres, although the option was never exercised.

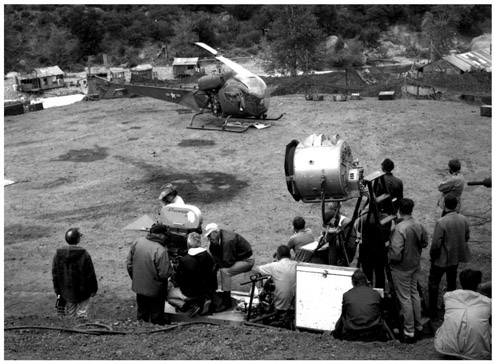

Filming the opening sequence of M*A*S*H (1970) at the ranch.

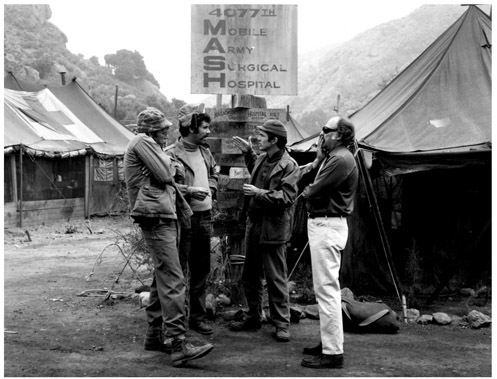

Donald Sutherland (far left) and Elliott Gould receive instructions during the filming of M*A*S*H (1970) which was shot on the ranch. Director Robert Altman is on the far right

In 1974 Twentieth Century Fox sold the property to the state for $4.8 million under a lease-back agreement in order to continue filmmaking there. Malibu Creek State Park was opened in 1976. In October of 1982 a devastating fire, believed to be arson, destroyed the M*A*S*H camp, except for one tent. Filming for the last seven episodes was subsequently adjusted. Although it remains a popular site for filming, Walter Pidgeon’s words for How Green Was My Valley (1941) are apt: “Something has gone out of this valley that may never be replaced.”

The M*A*S*H (1972-1983) TV show was also camped out here.

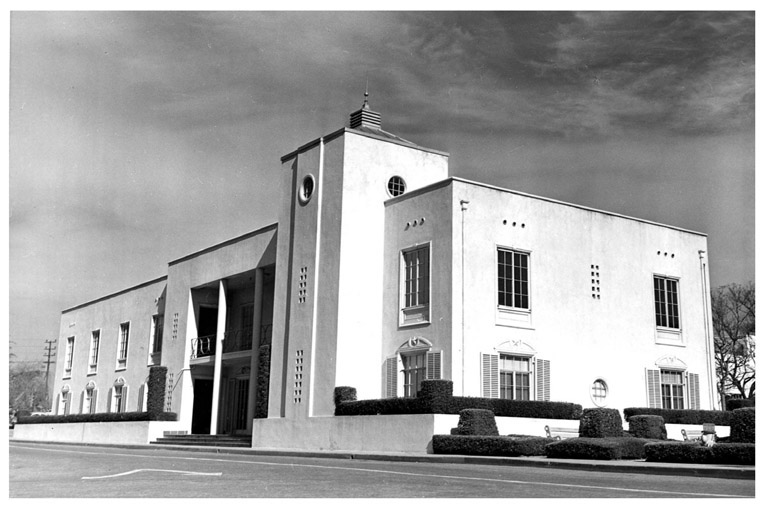

The exterior of Stage Eight, 2015.

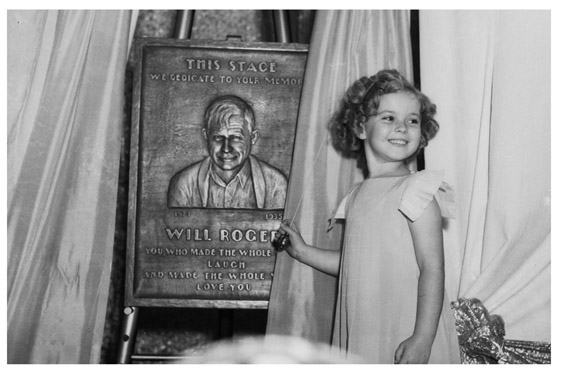

Shirley Temple unveils the plaque at the dedication of Stage Eight to Will Rogers in 1935.

The Fox Fire Department in front of the fire station that was located on the east side of Stage Eight with Olympic Boulevard just beyond, 1945.

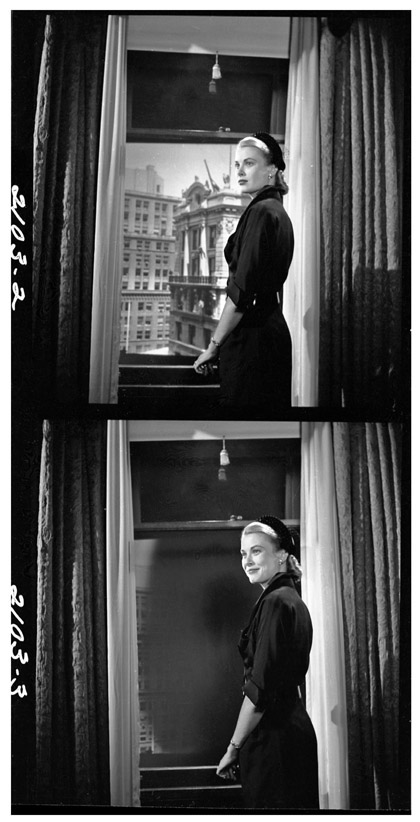

Grace Kelly loses composure when the rear projection is blocked during her first film role in Fourteen Hours (1951).

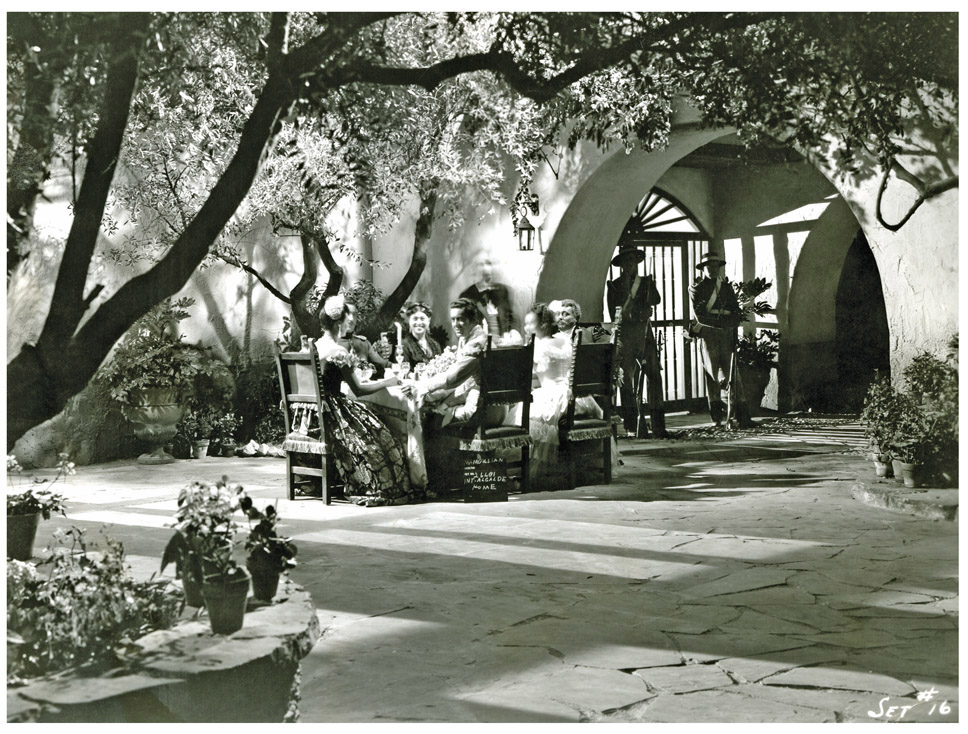

Tyrone Power evidently got distracted during rehearsal by the cameraman who took this set still of the hacienda for The Mark of Zorro (1940).

Helping to build this stage was Ed Conlon, whose father was fire chief in the station that once neighbored it. Hugh Conlon was in charge of the studio’s forty-seven volunteer firemen, shared with the Western Avenue Studio. The Conlons came here in June of 1926 when a friend sold Fox a fire truck and told them they needed someone to run the department. For two months their first home was a closed-in Tom Mix set, with plumbing installed, until the station and a permanent residence was built (Bldg. 139). Ed remembered that after building Stage Eight he worked in the mill before joining the fire department in 1938. He was made captain in 1961 when his father retired, and then chief of plant protection by Richard Zanuck in 1966. Father and son prided themselves that, until economic cutbacks, the Los Angeles Fire Department never had to lay a section of hose on the lot.

Stage Eight was dedicated to Will Rogers upon his death. Shirley Temple presided over the memorial service on November 15, 1935, and unveiled a copper plate that exists at the entrance to this day.

You made the whole world laugh and made the whole world love you. 1879–1935

Look closely and you might see Gregory Peck and Susan Hayward here in re-created Africa for The Snows of Kilimanjaro (1952).

Interesting trivia for Batman fans: The 1966 film was shot on this stage—the same one used for The Mark of Zorro (1940). The connection? In the 1986 comic reboot of Batman, as the Dark Knight Bruce Wayne’s parents go to see The Mark of Zorro the night they are killed, Wayne models his costume after Tyrone Power’s masked man.

When director Henry Hathaway chose Grace Kelly over Anne Bancroft, he made history here directing her on an office set for Fourteen Hours (1951). It was her film debut. Darryl Zanuck signed only Bancroft to a studio contract, which he regretted when Kelly became a much bigger star at MGM. Hathaway also regretted Zanuck’s decision to give the movie a happy ending. Hathaway had shot the main character (Richard Basehart) jumping to his death, but when Spyros Skouras’s daughter actually did jump from a window the day the picture was previewed, Skouras wanted the film destroyed. Six months later Darryl Zanuck added the new ending. Princess Grace of Monaco was later appointed a member of the Fox board of directors by Dennis Stanfill and served from 1976 to 1981.

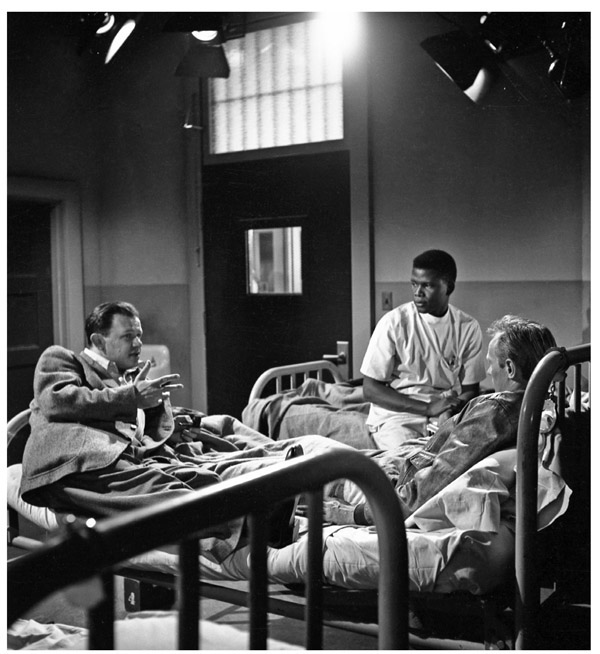

“Sidney Poitier does not make movies,” said film critic Vincent Canby, “he makes milestones.” No Way Out (1950) was the very first. Here Joseph Mankiewicz directs Poitier and Richard Widmark.

The County Hospital built here for Joseph Mankiewicz’s No Way Out (1950) is another historic set. It was the setting for Sidney Poitier’s unforgettable film debut as Dr. Luther Brooks, a black intern dealing with a racist patient (Richard Widmark). Poitier never forgot how supportive the cast, particularly Widmark, was. Joseph Mankiewicz and Darryl Zanuck produced it knowing it would not—and indeed, was not—screened below the Mason-Dixon Line. Ebony magazine praised it as one of the first honest films ever made about contemporary African-American life. That studio tradition would continue with The Great White Hope (1970), Waiting to Exhale (1995), and House M.D. (2004-12) starring the Image Award-winning Omar Epps as Dr. Eric Foreman. Forest Whitaker has had a productive studio partnership as director (Waiting to Exhale, Hope Floats), and actor (Phone Booth, The Last King of Scotland, Street Kings, Black Nativity, Taken 3).

Samuel Fuller’s Fixed Bayonets! (1951) is unique both for its single primary set, and for featuring among its “dogfaces” James Dean. When Ivan Martin complained to Darryl Zanuck that Fuller’s habit of shooting off a gun to get his stars’ attention was ruining the soundstage roof, Zanuck summoned Fuller to his “Z” Theater for a screening of the film. During a particularly tense scene Zanuck pulled out a gun and fired it. Fuller leapt for the exit, terrified—a lesson learned.

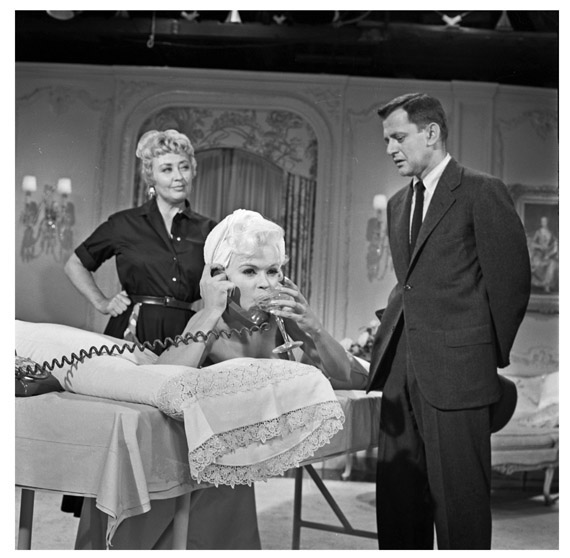

Jayne Mansfield once said: “The quality of making everyone stop in their tracks is what I work at.” She certainly did that earning lasting fame for playing, in characteristic over-the-top-yet-knowing style, roles like movie star Rita Marlowe in Will Success Spoil Rock Hunter? (1957). This is the stage where she made one of the funniest phone calls in motion picture history, using Tony Randall to make “jungle man” Bobo Branigansky (Mickey Hargitay) jealous. Mansfield and Hargitary wed in real life in January of 1958. After her tragic death she was portrayed in a TV movie by Loni Anderson, and Hargitay, by Austrian muscleman and future Fox star, Arnold Schwarzenegger.

And when Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev and his wife visited the Bal du Paradis set of Jack Cummings’s Can-Can (1960), Frank Sinatra informed them: “This is a movie about a lot of pretty girls, and the fellas that like pretty girls.”

Joan Blondell and Tony Randall learn from a master as Jayne Mansfield baits her boyfriend on the telephone in Will Success Spoil Rock Hunter? (1957).

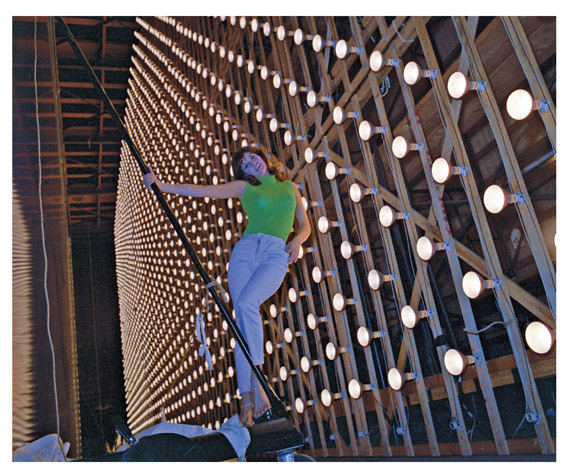

Raquel Welch hangs on to a wall of lights during the filming of Fantastic Voyage (1966).

Soviet Premier Nikita Krushchev and his wife watch a scene from Can-Can (1960) with Frank Sinatra and Juliet Prowse.

“Oh, what a day that was,” recalled costar Shirley MacLaine. “When I learned I was to be hostess of the whole event, I went over to UCLA to learn the language so I could welcome him properly. I must have been unclear about it, because when he got off the plane I greeted him in Czarist Russian!

“Those costumes were Irene Sharaff originals, and she insisted that they be the original fabric. My velvet costume weighed seventy-five pounds so that it would swirl and be effective. When we made the film we shot little sections, but in front of Khrushchev we had to do the whole dance, and I thought I was going to have a heart attack. During filming I was also witness to Frank falling in love with Juliet Prowse on the afternoon he sang to her, ‘It’s The Wrong Face.’ ”

The idol of Sinatra’s youth, Bing Crosby, made Say One for Me (1959)—the interior of the church—and High Time (1960)—his fraternity dorm room—here. The popularity of High Time’s “The Second Time Around” led to a Debbie Reynolds/Steve Forrest vehicle called The Second Time Around (1962), also made on this stage. All in the family: Crosby’s son Gary was under contract and appeared in Mardi Gras (1958) and Holiday for Lovers (1959), also shot here. Watch for Gavin MacLeod as a member of the faculty in High Time. He re-appeared on the lot as the captain of The Love Boat (1977–86).

Raquel Welch recalled the science-fiction classic Fantastic Voyage (1966), directed by Richard Fleischer, as eight months of hanging from wires on this stage. Tom Mankiewicz dubbed the five women Welch employed for public relations, wardrobe, hair, and makeup “the Raquettes.”

Now welcome to the world of the camp classic Valley of the Dolls (1967). Like Peyton Place it was based on a notorious novel, and the star was the hit television show’s Barbara Parkins, who lobbied for the part by going directly to Richard Zanuck’s office. Twenty-year-old Patty Duke was playing a part inspired by Judy Garland’s career. To complete the triumvirate of women facing show business, Sharon Tate earned the role initially earmarked for Raquel Welch, as the doomed Jennifer. The character was allegedly based on the tragic career of Fox’s own Carole Landis. Three years later Tate would be murdered by the Mansons at the age of twenty-six. Thirty years after she had made her feature film debut on the lot, Garland was signed for the role of veteran entertainer Helen Lawson. Parkins remembers working with her here in Lawson’s dressing room set until insecurity, medication, and depression over the script caused her to be replaced after only a few days by that old Fox pro, Susan Hayward.

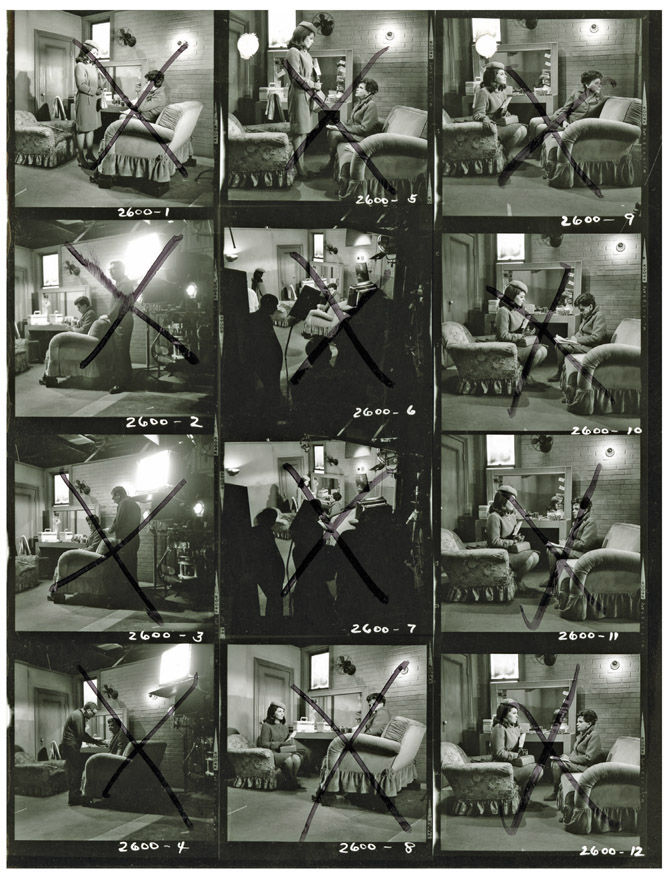

Judy Garland and Barbara Parkins in a cut scene from Valley of the Dolls (1967).

Blake (John Forsythe) and Krystle (Linda Evans) Carrington’s mansion interior set was built here for Dynasty (1981–89).

Judy Garland in her film debut, Pigskin Parade (1936).

Bruce Willis in front of the mural on Stage Eight celebrating the successful Die Hard franchise

To commemorate the twenty-fifth anniversary of the Die Hard franchise, and to promote the release of A Good Day to Die Hard (2013), a mural depicting Bruce Willis in a scene from the first film was painted on the east side of the building.

Stars’ Dressing Rooms, view from northwest corner soon after construction.

View from southwest corner.

View of east façade.

With the demand for more room for Fox’s female stars, this Regency Revival building, by Beverly Hills designer Douglas Honnold, replaced the Café de Paris’s formal garden. It was the first built under Darryl Zanuck’s expansion plans under the direction of engineer J. A. Barlow. Male stars eventually moved in upstairs and throughout the building, in its fourteen suites lettered “A” through “N.”

The building still features decorative gold stars above each window, memorializing Darryl Zanuck’s brilliant constellation of talent who once lived within. Alice Faye was the first to receive “M,” the largest dressing room in the southeast corner of the building, on the ground floor. While dating Tony Martin, Faye asked neighbor Jane Withers to come over if she knocked on her wall—the signal that Martin’s amorous advances were going too far. Betty Grable, Joan Crawford, and Marilyn Monroe later occupied that suite.

When Henry King turned down Don Ameche in favor of Tyrone Power for Lloyd’s of London (1937), he launched Power’s legendary career that included such fringe benefits as the equally spacious “E” suite, directly above on the second floor. Power was introduced to his first wife, actress Annabella, in the hallway here by a wardrobe woman before they began Suez (1938). Like other big stars on the lot, Power had his own secretary, stand-in, and wardrobe designer. Zanuck was indulgent and, rare for the mogul, a friend to this star. After Will Rogers was killed he seldom allowed his top talent to fly, but Ty did, flying over the studio late at night with Howard Hughes, and then buying a plane from Hughes to fly elsewhere. When Power playfully carved “DZ” instead of a “Z” in a take for The Mark of Zorro (1940), Zanuck got back at him by turning off the heater in the administration building’s swimming pool, which he allowed Power to use.

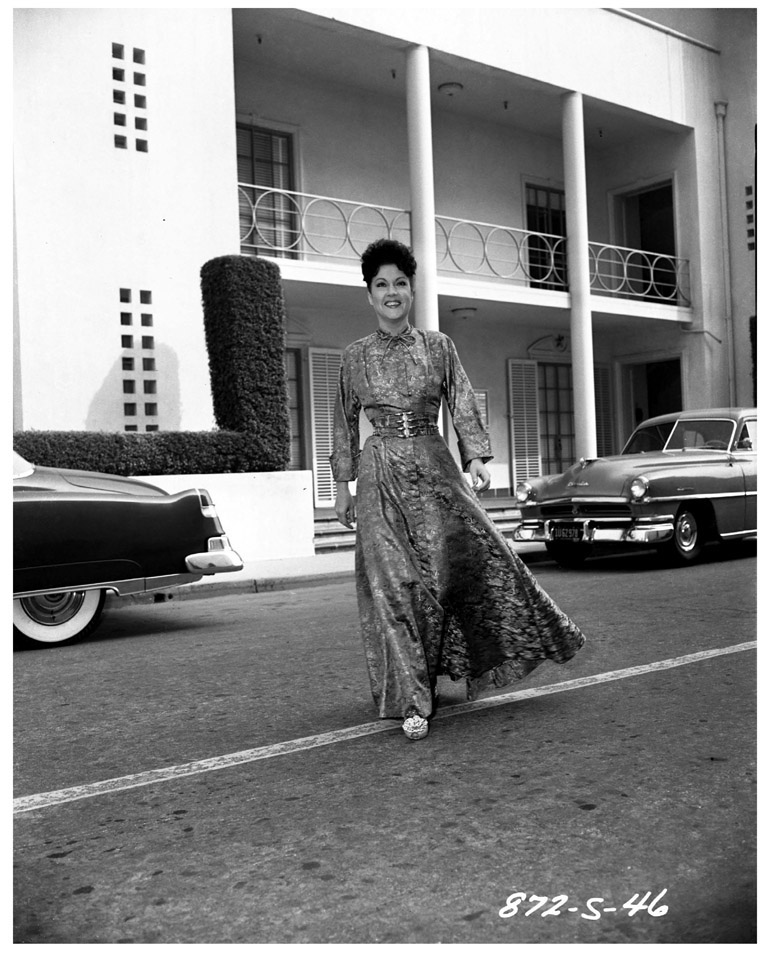

Like Withers, Ethel Merman and Cesar Romero had a lot of fun on this lot. For example, there was the time Harry Brand tried to cook up a romance between them during filming of her Fox debut Happy Landing (1938).

“He wasn’t free with a buck, to put it mildly,” she said. “So every time an item about us appeared, I’d order a beautiful floral arrangement for myself, have his card attached and charge it to his account. Upon its arrival, I’d thank him profusely and he’d sputter, ‘I never ordered that.’ On one occasion a hearse drew up to collect the body. Guess who was behind all this?”

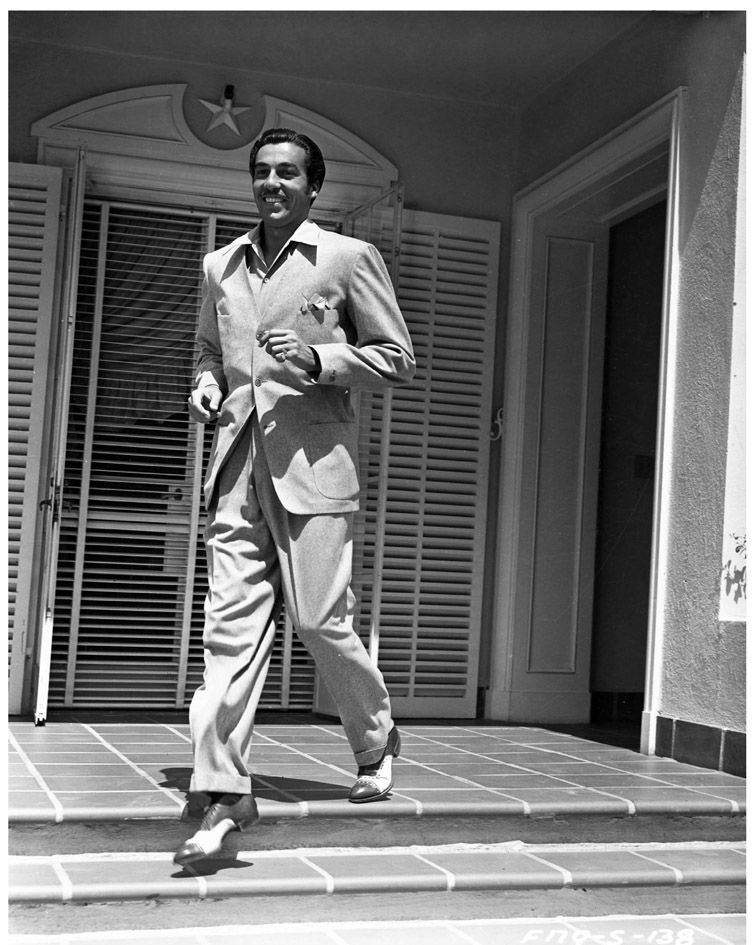

No one enjoyed his Latin Lover image more than the suave Romero. It showed and audiences loved him for it in more than forty Fox films. No doubt William Dozier’s most inspired casting decision for his Batman TV series was casting Romero as the Joker.

In the 1940s Gene Tierney proudly led what she dubbed “The Fox Girls”—including best friend Cobina Wright Jr. and Linda Darnell, who brought her pet rooster that showed up in Chad Hanna (1940). Among Roddy McDowall’s “chums” was Henry Fonda. Their contests to see who could hold their breath longer were recorded on Fonda’s dressing room wall. Another handsome face around here was George Montgomery, who can be seen around the lot with “B” favorite Mary Beth Hughes in The Cowboy and the Blonde (1941). His wife Dinah Shore later hosted the popular Fox TV show, Dinah! (1974– 80). Dana Andrews recalled having his apartment next to Alice Faye’s and enjoyed spending more time there. Dana’s younger brother Steve Forrest debuted in his Crash Dive (1943), and later starred in the Spelling/Goldberg hit S.W.A.T. (1975–76) on the lot. Jennifer Jones preferred arrangements of lemons rather than flowers in her dressing room. “I’m easy keep,” low-maintenance Anne Baxter told the matron who was running this building when she moved in. As persevering as Betty Grable despite unsuccessful bit parts as Frank McCown—try and find him in Something for the Boys (1944), Sunday Dinner for a Soldier (1944), The Bullfighters (1945), and Nob Hill (1945)—Rory Calhoun earned a spot in these hallowed halls playing characters audiences enjoyed rooting for like Jack Stark in I’d Climb The Highest Mountain (1951). He dated Jeanne Crain, but she preferred to marry former actor Paul Brinkman. In the 1950s Clifton Webb inherited Tyrone Power’s dressing room and was enthroned there as the studio’s social lion. “He was very social and very dear in his way,” recalled Myrna Loy. “It just had to be his way.”

Terry Moore arrived on the lot with fellow Columbia contract player Marilyn Monroe and was established here in 1952 with an apartment on the first floor on the north end. Of the others she remembered seeing in the building—Robert Wagner, Don Murray, Jeffrey Hunter, Jeanne Crain, and Jean Peters—she only had trouble with Peters (“We were all so competitive!”), who was dating Howard Hughes at the same time she was. She married Hughes in 1949, but Hughes publicly married Peters a few years later.

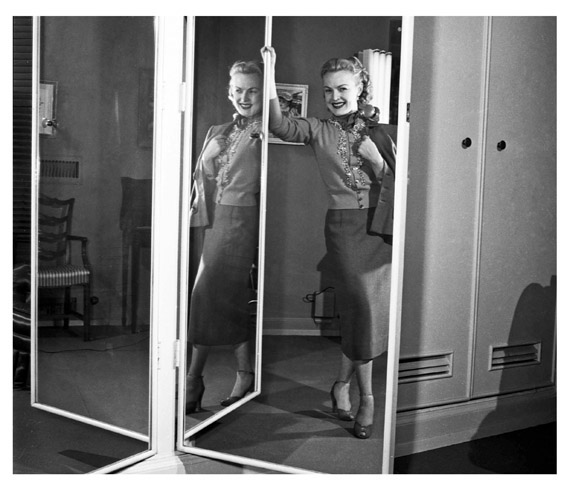

Buddy Adler gave his new contract players Don Murray and Hope Lange a week off in April of 1956 to get married during production of Bus Stop (1956). Because his fame preceded hers they shared a dressing room here with his name on it. “It’s useful having a husband who rates a lay-out like this,” Lange (known as “Hopie” on the lot) said. “I’d just as soon go on using Don’s dressing room. Everyone expects me to anyway.”

The formal garden that existed on the site prior to construction, 1934. The Colonial Home and Chateau Tokay can be seen across Olympic Boulevard.

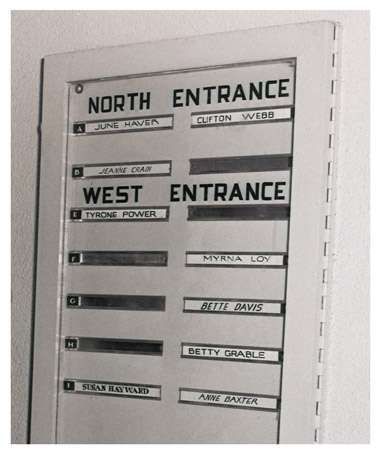

Directory showing who occupied the suites on October 31, 1951.

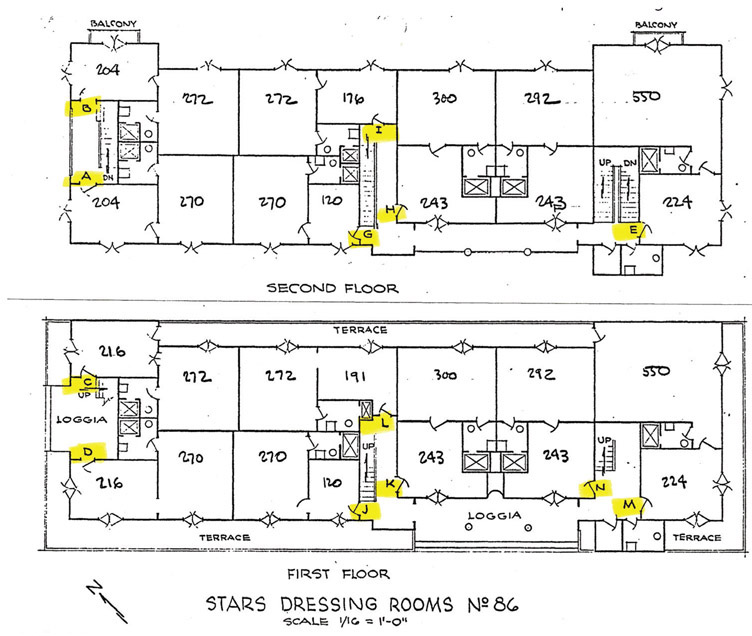

Floorplan showing the layout of the original dressing room suites. The letters by the doors indicate the suite names and the numbers indicate the square footage.

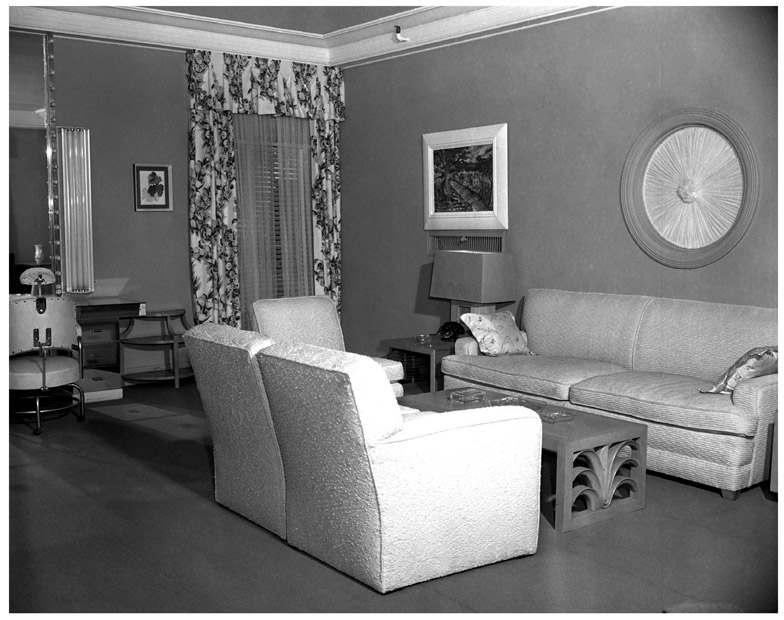

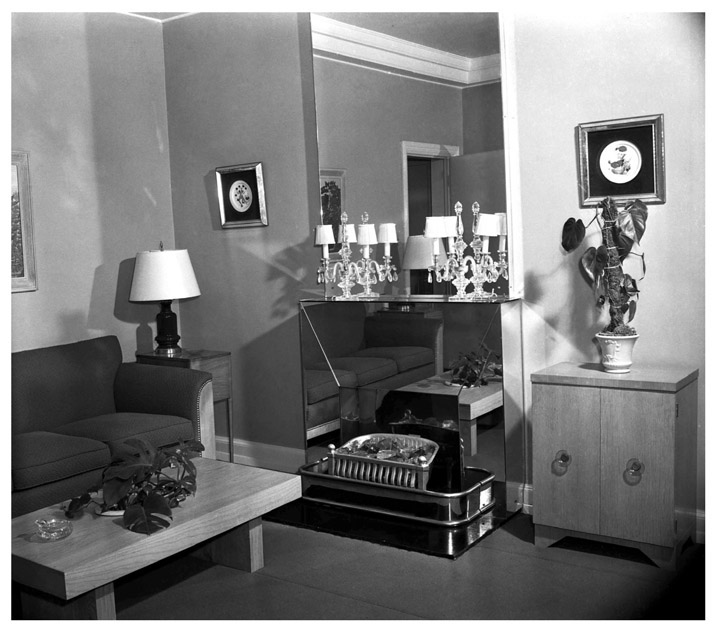

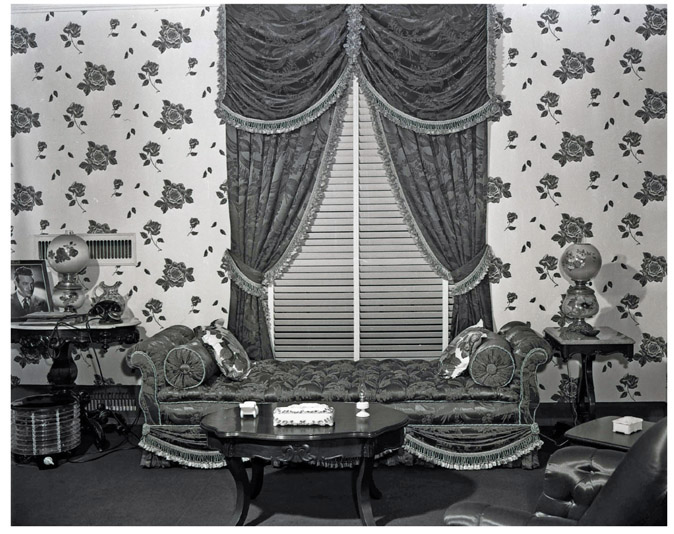

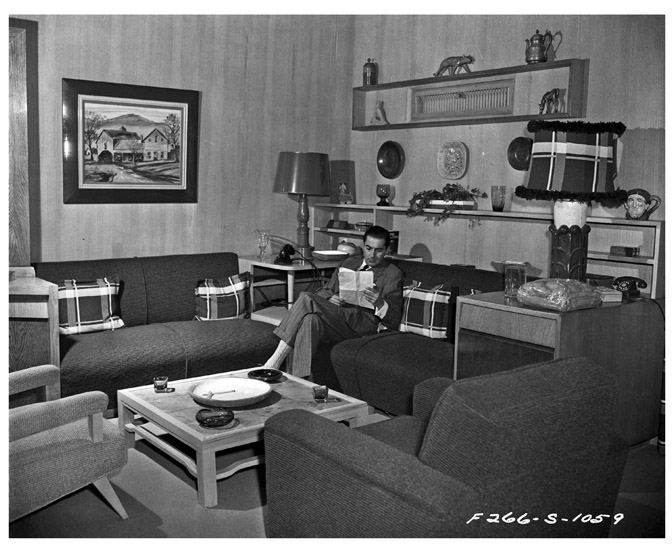

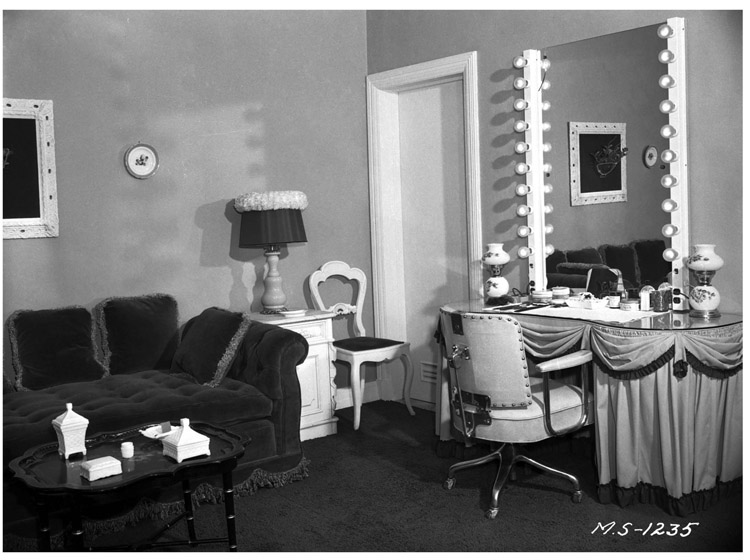

The huge dressing room “M” as decorated for Joan Crawford in mid-century modern. It remained much the same when it was Marilyn Monroe’s in the 1950s.

The sitting room of dressing room “M” as decorated for Joan Crawford in 1947.

The porthole on the east wall of dressing room “M” was removed when the main room was split into two offices. This is how the exterior appeared in 2015.

Dark beauty Dana Wynter (“I pronounce it Donna because that sounds more feminine”) made her American film debut in The View from Pompey’s Head (1955), a quintessential Zanuck 1950s movie mixing soap opera and social conscience in a literary strain.

Russ Tamblyn recalled having a dressing room across from Robert Mitchum while he made Peyton Place (1957). In the early mornings, after visiting the makeup department and waiting for shooting to start, he would find Mitchum here with triple-shot vodkas with orange juice for breakfast. Once, refusing to answer the telephone, Mitchum threw it out the window. “[Mitchum’s] air of casualness or, rather, his lack of pomposity is put down as a lack of seriousness, but when I say he’s a fine actor, I mean an actor of the caliber of Oliver, Burton, and Brando,” said John Huston.

Alice Faye in the huge dressing room “M”, 1939.

Susan Hayward did some of her best work on this lot, and despite the tough, even manipulative, parts she played that earned her the title “Wayward Hayward,” employees recall her with great affection. “The wardrobe girls, the makeup men, the crew—they all seemed to like her very much,” recalled Fox publicist Sonia Wolfson. “I never heard any of them say an unkind thing about her.”

A chauffeur waits for Loretta Young outside Building 86, 1937.

Betty Grable shows her patriotism with this shirt displaying all of the emblems of the armed forces as she stands in the loggia on the first floor, circa 1945. The black mark indicates that the studio thought that her shirt should be a bit longer.

By the time the former Queen of the Lot had returned to make The Marriage-Go-Round (1960), the building’s glamour was fading with the end of the stars-under-contract system. Pat Boone, one of the last to sign a seven-year contract during this period, remembers his apartment as the one closest to the commissary, where the food was.

Betty Grable touches up her makeup in her elegant dressing room, 1946.

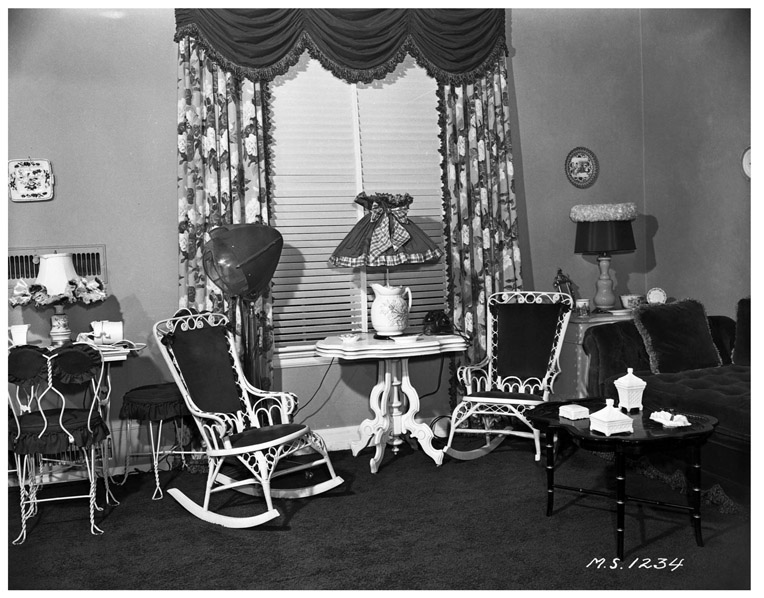

Betty Grable’s dressing room decorated in an ornate Victorian style. Note the picture of husband Harry James on the table at left, 1947.

Maureen O’Hara’s dressing room decorated in an 18th century English style, 1947.

Television stars soon replaced movie stars in the dressing rooms, until they became offices in the mid-1970s. The building was redesigned to its current look for Lawrence Gordon’s production company—including enclosing the porches and staircases with steel and glass—in 1986. Chris Columbus’s production company, 1492 Productions and Knickerbocker Films Production (Fight Club, 1999), have been housed here. Currently the In-Theatre Marketing group resides within. Of course, it has appeared in numerous movies (Mardi Gras, 1958), and television shows (Peyton Place).

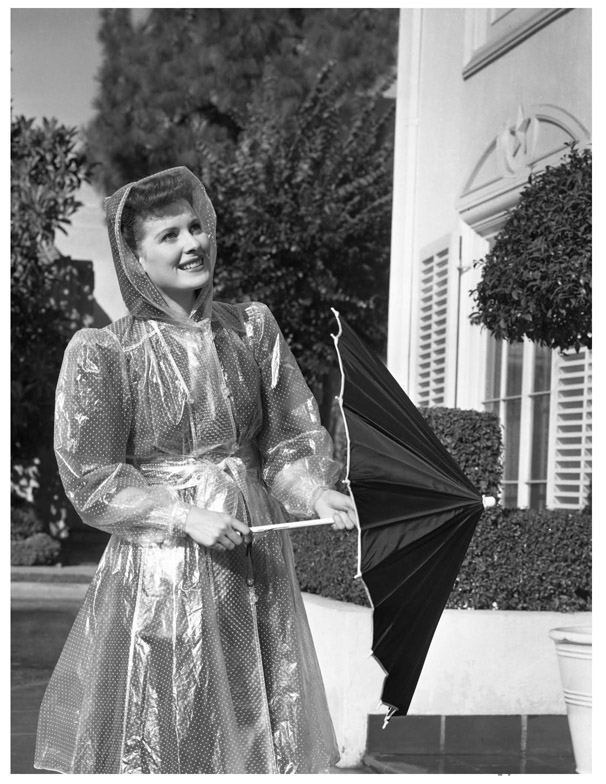

Maureen O’Hara, standing at the north end of Building 86, apparently doesn’t believe that it never rains in southern California, 1941.

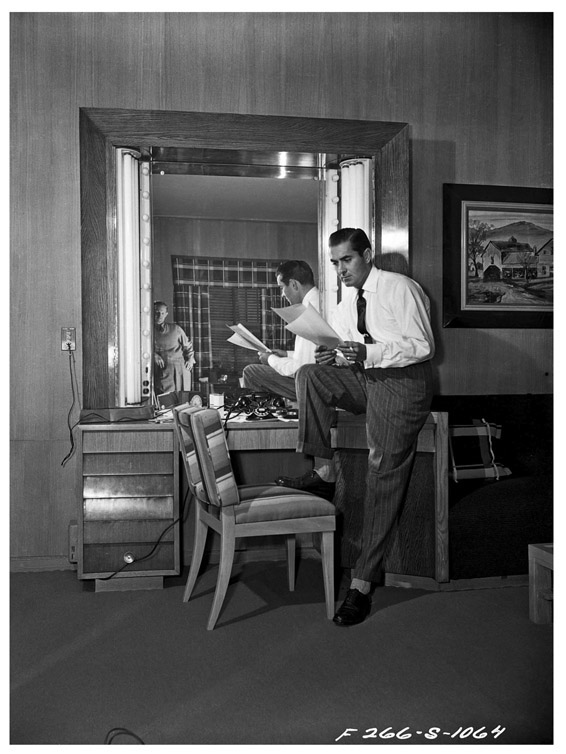

Tyrone Power at his vanity in dressing room “E” on the second floor, 1948.

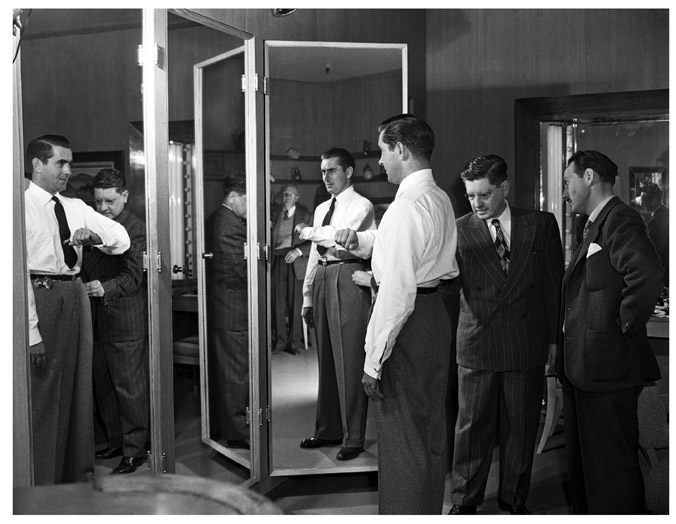

Tyrone Power gets properly fitted in his large dressing room.

Tyrone Power does some reading in his dressing room.

Ethel Merman in front of Building 86 during the filming of Call Me Madam (1953).

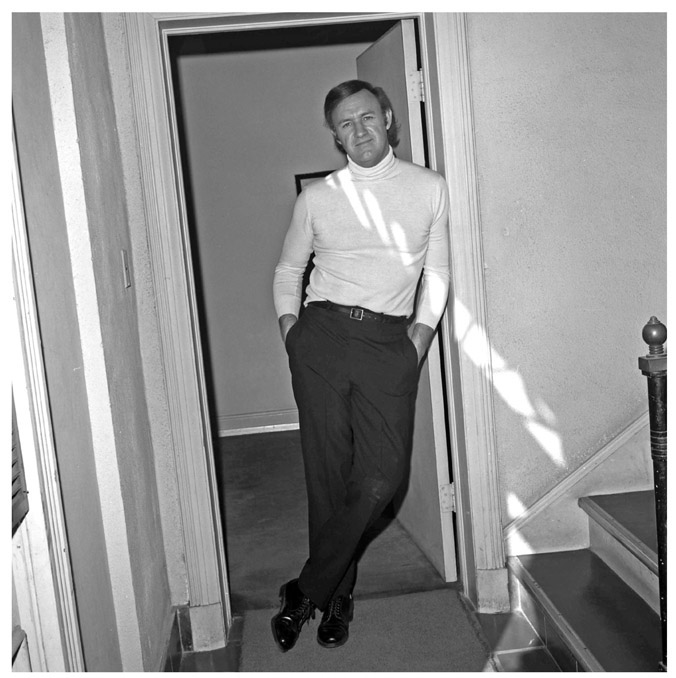

Cesar Romero in a hurry, circa 1939.

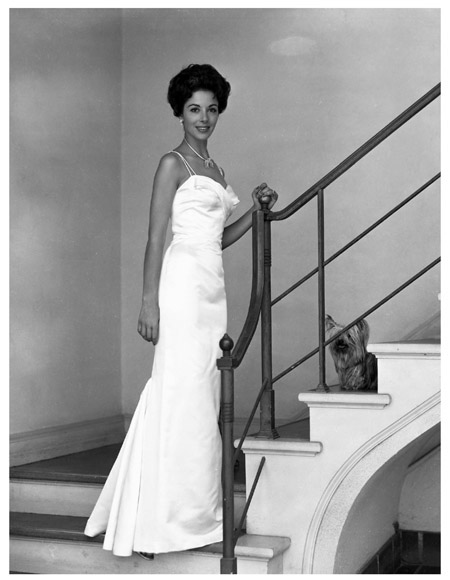

Gene Tierney is all dressed up for rainy weather, 1942.

Gene Tierney’s room decorated in a Gay Nineties theme, 1947.

Gene Tierney’s vanity.

Linda Darnell, seen in the reflection, in her modern dressing room, circa 1947.

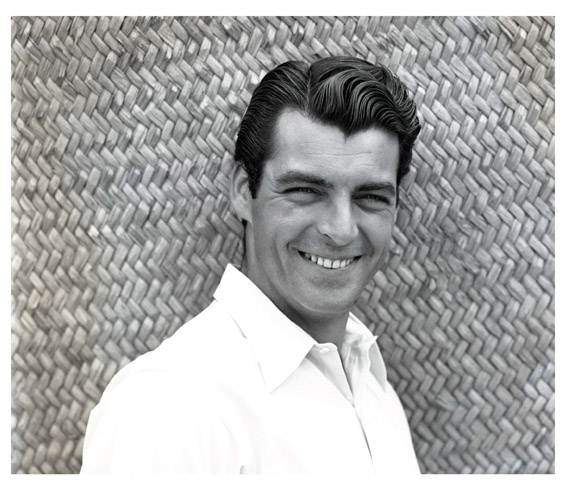

George Montgomery, 1942.

Jennifer Jones stands in the first floor loggia, 1943.

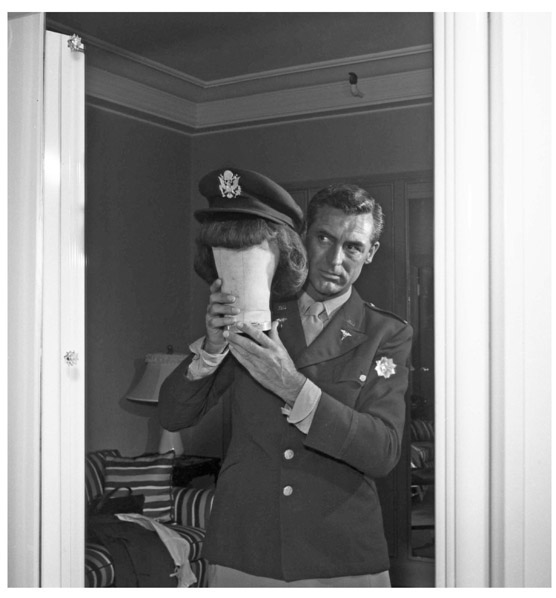

Cary Grant checks out the wig he will wear in I Was a Male War Bride (1949).

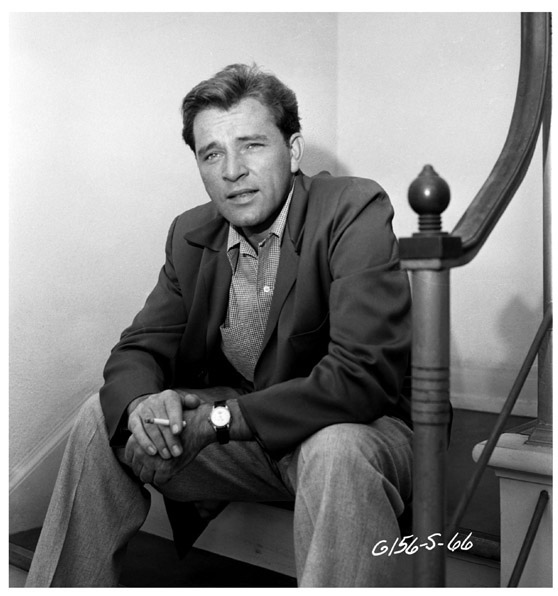

Richard Burton sits on the north stairs of Building 86, 1954.

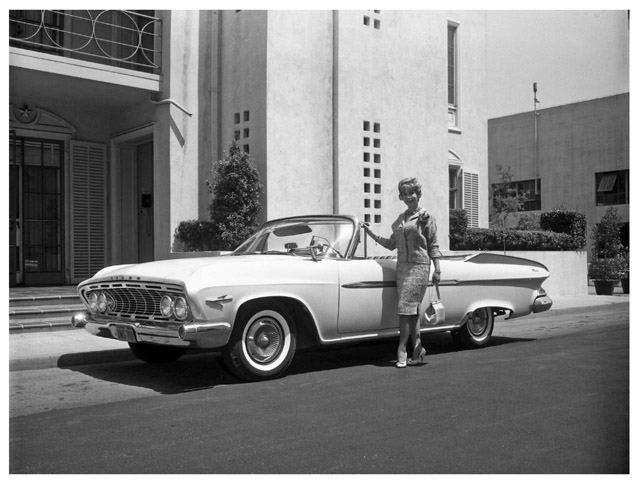

Lauren Bacall poses in front of one of the concept cars created by Ford for Woman’s World (1954) at the north end of Building 86.

June Haver in her dressing room, 1952.

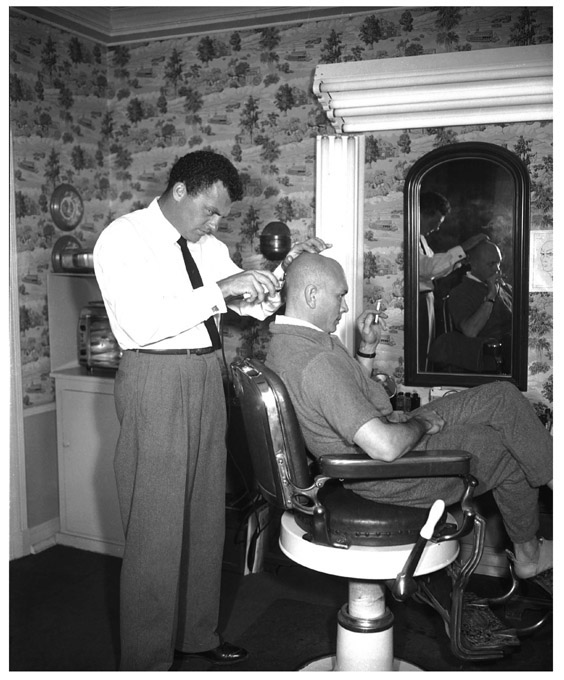

Yul Brynner gets his head shaved for his role in The King and I (1956) in his Early American dressing room.

This is how the dressing room appeared a decade earlier when Douglas Fairbanks, Jr. was there for That Lady In Ermine (1948).

Rory Calhoun, 1951.

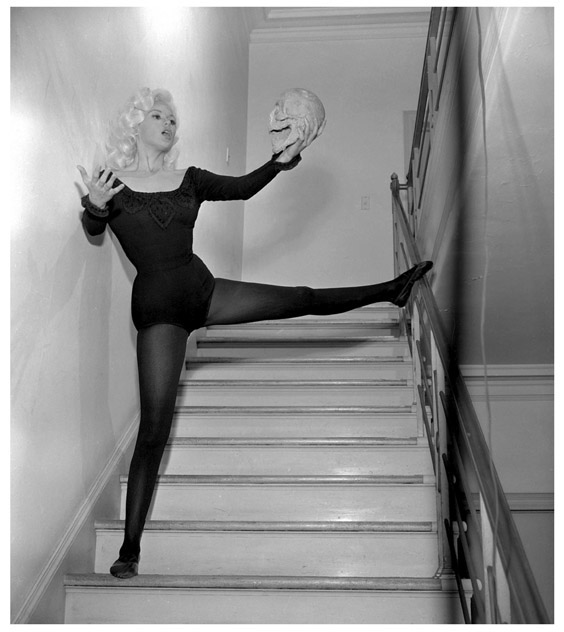

Jayne Mansfield (performing Hamlet???) on the central staircase, circa 1957.

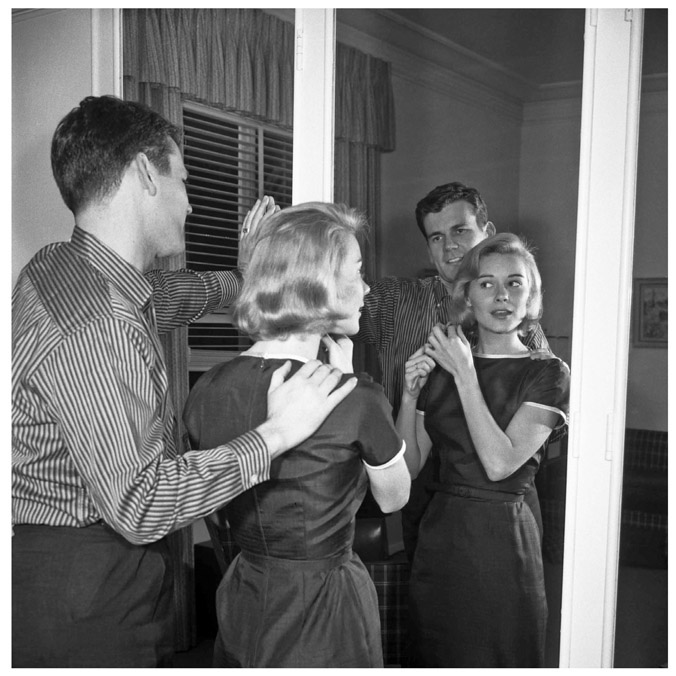

Don Murray and wife Hope Lange in their dressing room, 1958.

Elegant Dana Wynter on the north staircase, 1958.

Barbara Eden strikes a fashionable pose outside Building 86, early 1960s.

For decades, the most beautiful women at Fox sat at this dressing table getting ready for their closeups including Alice Faye, Betty Grable, and Marilyn Monroe. This is how dressing room “M” appeared in the mid-1960s.

Gene Hackman, in costume for The Poseidon Adventure (1972), stands in the doorway of dressing room “C.”

The bell installed on the east side of Building 86 came from the church that stood on Tombstone Street on the backlot.

View of the west façade, 2007.

Fox Plaza Tower

Announced in April of 1984, the Fox Plaza Tower was planned as a new world headquarters for the company. The brainchild of Marvin Davis, the Tower and the adjacent Galaxy Way parking structure and what is now the Intercontinental Hotel were built by the Miller-Klutznick-Davis-Gray Company, replacing Rehearsal Hall #2, Bldg. 84 (the old coffee shop that had become wardrobe storage), the transportation, grip, and electrical storage departments.

Fortunately that is as far as Davis’s plan—to raze the rest of the lot for residential and commercial use—got. On the six-acre site, chosen because of its natural elevation over Olympic Boulevard, architect Scott Johnson of Pereira Associates created the thirty-four-story, 711,000-square-foot tower of coral red granite and blue-tinted glass, with an underground parking garage featuring walls of fluted precast concrete panels as its base. Davis leased the twenty-ninth floor as his headquarters.

Even before it was finished production designer Jackson DeGovia put it in the movies in Die Hard (1988). It also appears in Lethal Weapon 2 (1989, Warner Bros.), Motorama (1991, Columbia), Airheads (1994), Speed (1994), Tommy Boy (1995, Paramount), and Fight Club (1999). The top floor of the building was leased by the Ronald Reagan Presidential Foundation. Reagan occupied office space here after leaving the White House in January of 1989, until his death in 2001. The building is currently owned by the Irvine Company. Fox rents about half of the floors for departments, including legal, human resources, and home entertainment.

The Commissary and Studio Store, 2007

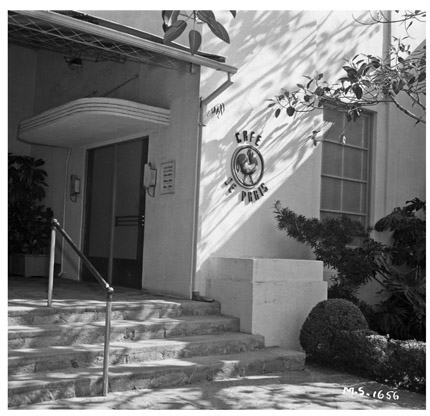

“We ate out of box lunches in the wilds of Westwood,” an unnamed studio vet remarked of the lot’s earliest days. “When the Café de Paris opened—well, it was a far cry from the old Munchers on Western Avenue!”

Indeed it was. Inspired by the cafes found in the Bois de Boulogne in Paris—but looking more Mediterranean with its tile roof—it took its name from the famed Cafés de Paris near the casino in Monte Carlo and the famous nightclub in London’s West End. To prove that Fox was just as chic, “perambulators” (silver-domed food-service trolleys) were purchased. It was not open to the public, and even employees had to get a special pass. Built during the summer of 1929, the Café was dedicated on September 12 in a ceremony with Will Rogers and actress Fifi D’Orsay as part of their premiere activities for They Had to See Paris (1929). Rogers became a regular here, eating hearty meals at a favorite corner table with Coca-Cola, which he dubbed “the champagne of America.” Spencer Tracy, who dined with him, recalled that those fortunate enough to do so never paid the check. “Rogers was first to the café,” reported Douglas Churchill in the New York Times, “and in the parade that paused at his table were some of the great and near-great of the world.”

The Café de Paris as it appeared in the early 1930s. The Sound Building is on the left.

Fifi D’Orsay and Will Rogers, stars of They Had to See Paris (1929) dedicated the Café de Paris as part of the premiere activities for the film.

The bell from Westphalia.

Interior of the commissary before the mural was painted, looking southwest, circa 1929.

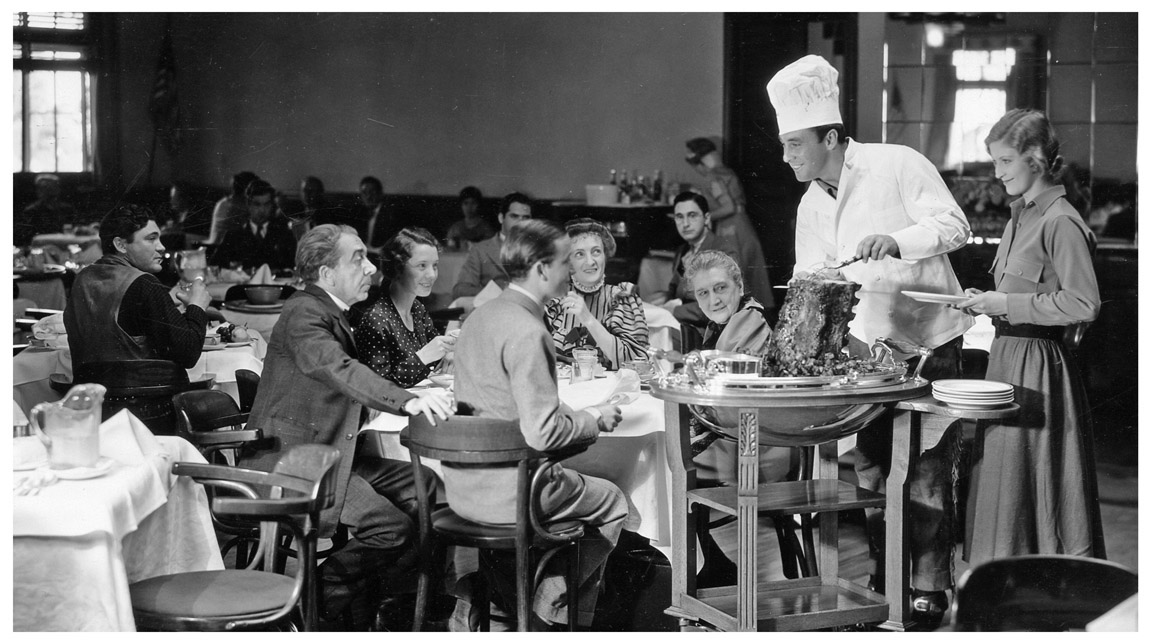

Original 1933 caption: “ ‘ Will you have it rare, sir?’ asks George O’Brien, Fox Films Western star as he prepares to serve a roast of beef to the British players in Cavalcade at the studio café. Those at the table are Herbert Mundin, Merle Tottenham, Frank Lawton, Una O’Connor, and Tempe Piggott, while Janet Chandler is George’s decorative assistant.” The studio was very proud to have perambulators for food service just like Simpson’s in London and Ciro’s in Paris.

The entrance to the Studio Store was the original main entrance, a porch known as the “Sun Room” that had windows with removable glass panels to allow terrace dining for 150 guests. Later, the front doors were locked, and the Sun Room became a semiprivate dining room called the Silver Room, used for cocktail parties, press announcements, executive luncheons, and other special functions, like Shirley Temple’s birthday parties. The room was completely enclosed in the 1950s, and in the early 1960s it was outfitted with projection equipment so that it could double as a screening room. The Studio Store, selling officially licensed Fox merchandise, opened there in November of 1986.

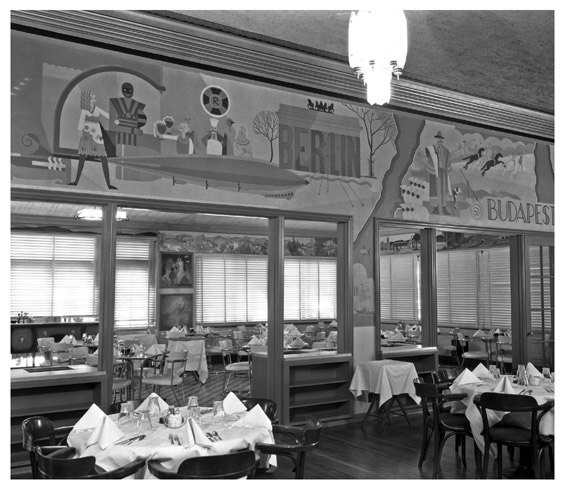

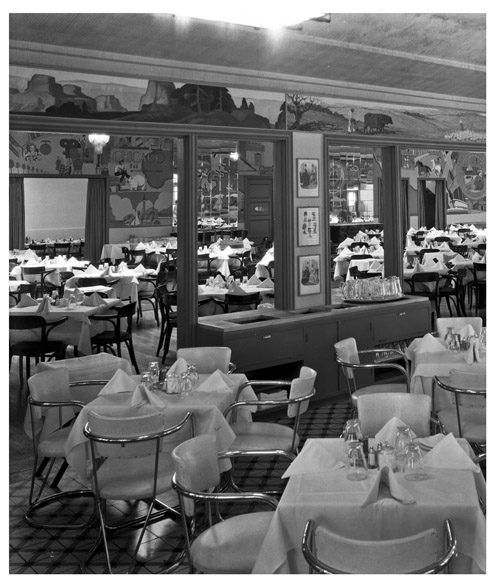

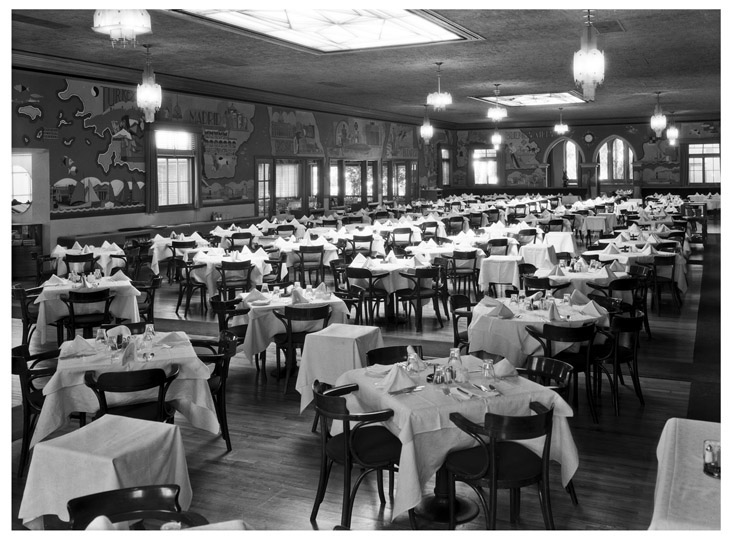

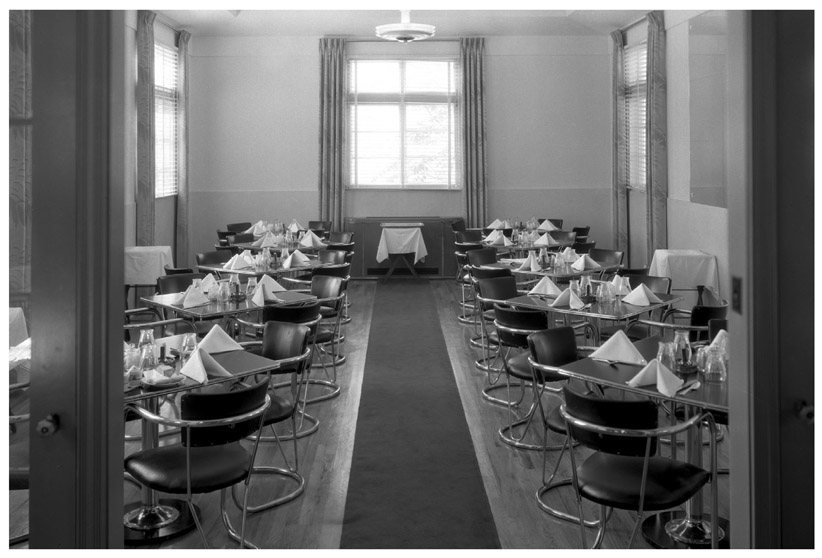

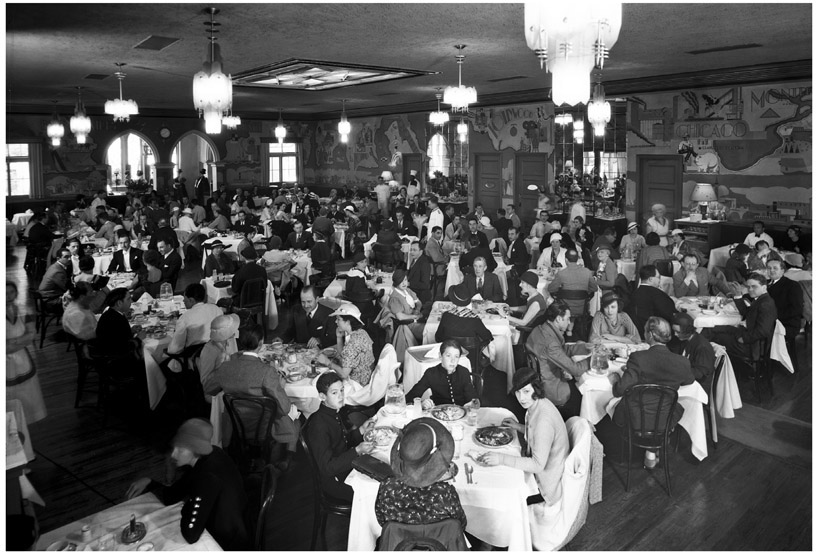

When it opened in 1929 the main dining room seated three hundred, and was about the size of the sit-down service area of 2015. In fact, the wall separating the cafeteria and the sit-down dining room is approximately where the original south wall stood. The floors were wood with carpet runners to soften the sound of foot traffic. The ceiling had a large rectangular skylight and alternating, delicate glass pendant light fixtures. Square and round tables covered in white linen and dark bent-wood chairs filled the room.

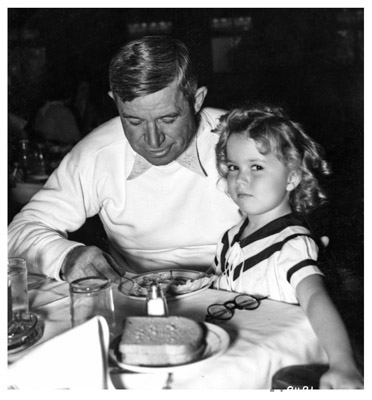

Will Rogers and Shirley Temple, two of the biggest stars at Fox, in the Café de Paris circa 1934.

There were two private dining rooms. The one on the east side became known as the Shirley Temple Room, although it was never exclusively hers. In the mid-1930s, etchings of scenes from Henry King’s film Marie Galante (1935) by French artist Edouard Chimot hung on it walls. Today ten portraits of Shirley Temple hang there. The second private dining room had a beamed ceiling and a fireplace. It disappeared during the 1936 renovation.

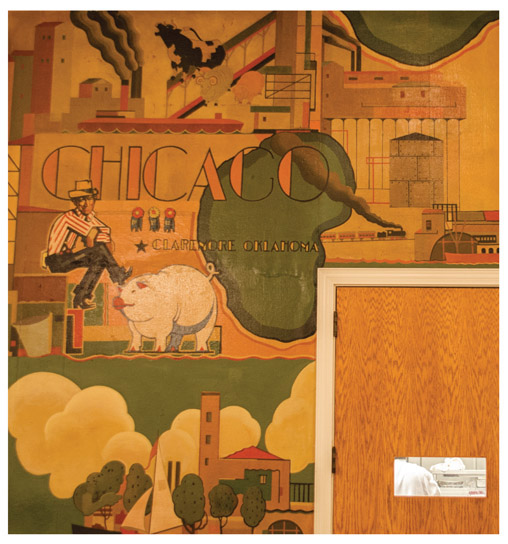

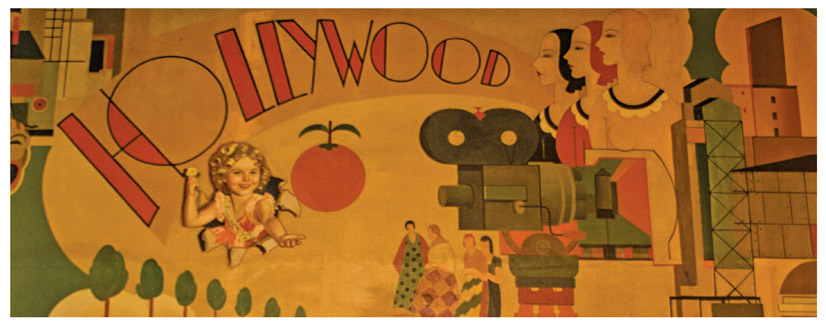

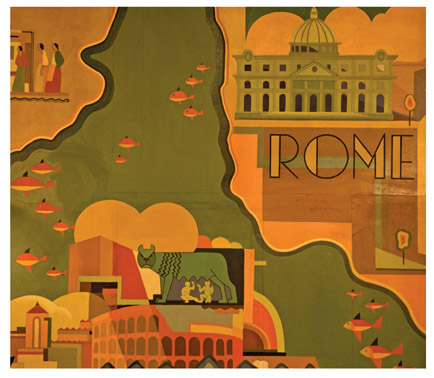

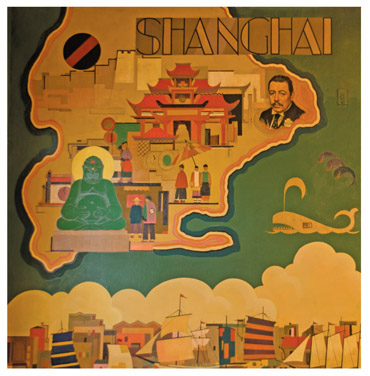

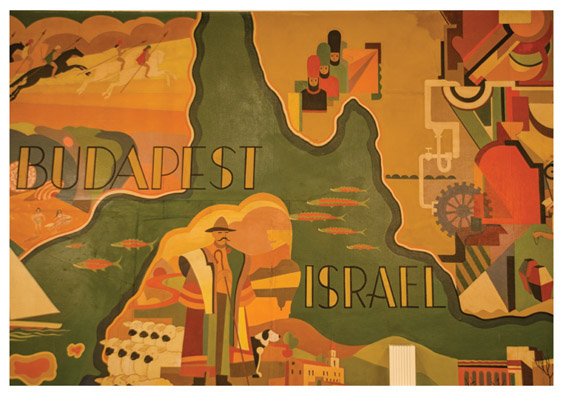

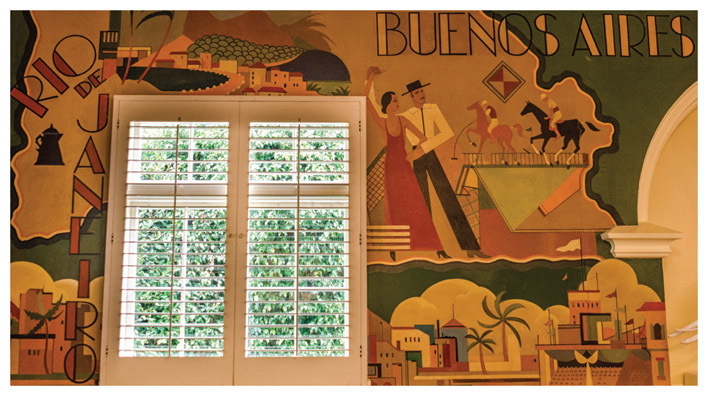

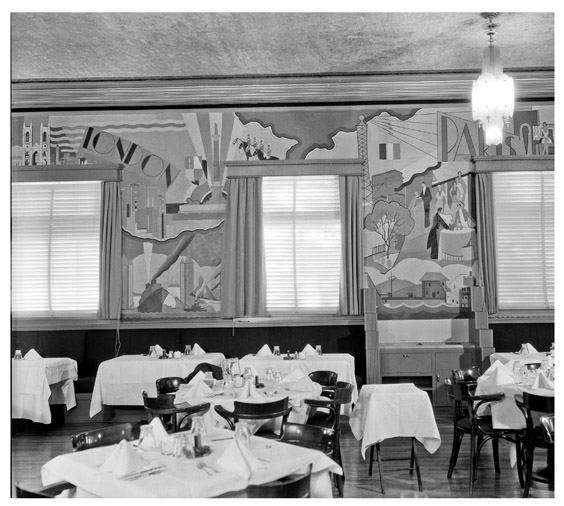

The white walls of the main dining room remained unadorned until 1932, when Winfield Sheehan commissioned esteemed Southern California painter Haldane Douglas to paint a mural. Conceived as a tour of the world stopping at all of the studio’s major film distribution capitals, it was originally 2,160 feet in length, took four months to paint, and was completed by the end of December. When the mural was restored in 2013, it was discovered that a light brown wash had been applied to it at some point to tone down the colors.

Douglas added several lighthearted items that Sheehan later ordered removed, including a sign pointing “To Reno” in the Hollywood section (not important enough of a city), gangsters in Chicago, and a battleship in London (the French consultant felt that this left France undefended). Originally there were only two celebrity portraits: Janet Gaynor surfing in Hawaii, and Will Rogers with “Blue Boy” the pig from State Fair (1933), in his hometown of Claremore, Oklahoma. When other stars complained, a policy was set that portraits could be added after ten successive box-office hits. Warner Baxter made it, and then Shirley Temple, Warner Oland, Alice Faye, and Darryl Zanuck, who is not surprisingly largest of all.

The mural was enlarged during the 1936 expansion, presumably by Douglas, who was then an art director and color consultant for Fox’s foray into Technicolor. There have been minor alterations over the years due to political changes (Palestine became Israel), and the repositioning of walls in the 1976 renovation. Some of the additions do not exactly fit the original theme—no one seems to know why the state seal of New Hampshire was inserted—but overall the changes over the years have been tastefully done to keep the tone and feel of the original.

H. Keith Weeks ran the Café until 1934, when Nick Janios became the Café’s general manager and maître d’. This lot legend held restaurant jobs as busboy, waiter, captain, maître d’, and catering manager at such Broadway landmarks as Churchill’s and Healy’s before being invited to Hollywood in 1927 to manage the world-famous Brown Derby restaurant on Wilshire Boulevard, and then open three more Derbies. He took credit for inventing the Cobb Salad named for the late Derby proprietor, Bob Cobb. Under his management the Café became, according to Fortune magazine, “the most luxurious studio restaurant in Hollywood.”

Looking into the Silver Room, 1938.

Shirley Temple makes her social debut as hostess at her sixth birthday party in 1934 in the Silver Room. This was the first birthday party given to her at Fox and they just kept getting bigger and bigger. In later years, her parties would be held in the main dining room to accommodate the guests.

Original 1935 caption: “A FARMER’S BIRTHDAY PARTY—The members of The Farmer Takes a Wife company at Fox Film studio give Henry Fonda, new leading man, a birthday party. Left to right, Victor Fleming, director; Henry Fonda, Janet Gaynor, and G. S. Yorke, director of publicity. The party was held at the studio café [in the Silver Room]. The table was decorated in rural style, the menu quite similar to old-fashioned farm proportions, and the favors were packets of garden seeds.”

Looking out of the Silver Room, 1938.

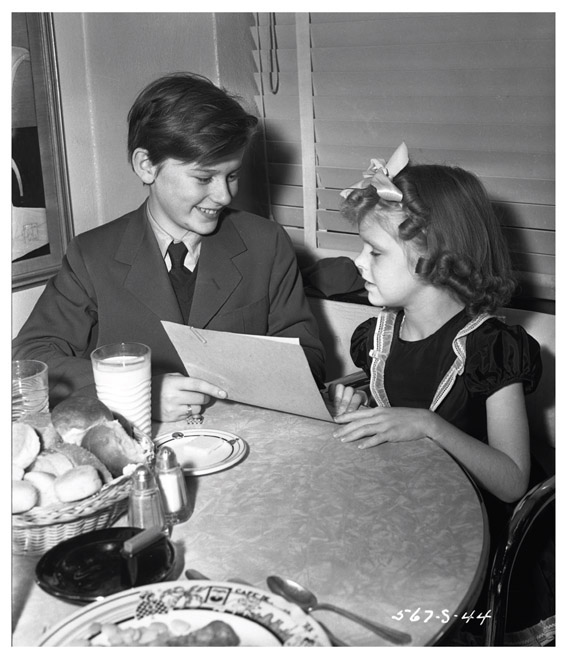

Roddy McDowall and his sister Virginia in the Silver Room, 1942.

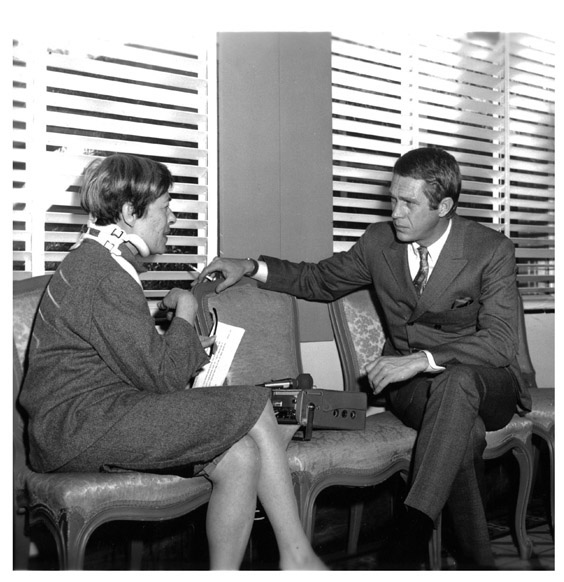

Steve McQueen is interviewed for The Sand Pebbles (1966) in the Silver Room when it was decorated as the Peyton Place Inn for the TV show.

Orson Welles, in costume as Rochester from Jane Eyre (1944) greets visitors at a luncheon.

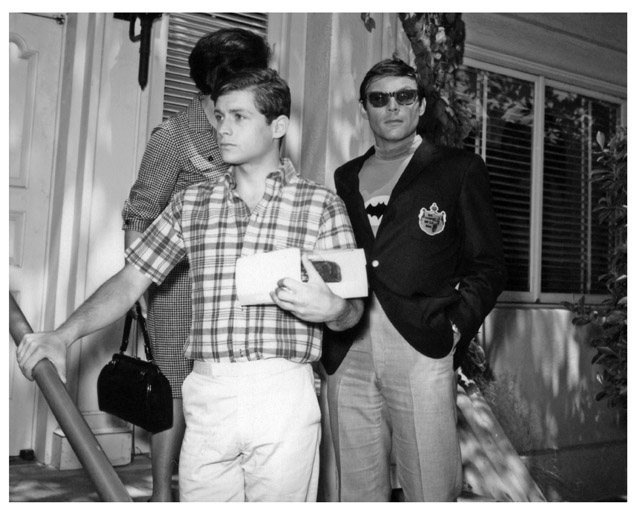

Burt Ward and Adam West, stars of the original Batman (1966) TV show, exit the Silver Room.

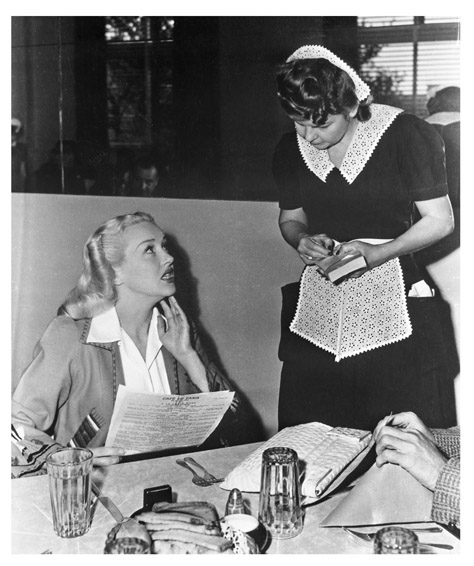

With up to four thousand employees during the studio’s peak years (1935–49), the commissary served six hundred to twelve hundred of them every day. Staff included a kitchen crew of forty-one, sixteen busboys, two cashiers, three hostesses, thirty-two waitresses, and pastry cook Alfred Ulrich. Ulrich remembered that creamed chicken and peas on toast became a house specialty because it got little Shirley Temple to eat her peas; Tyrone Power loved ox joints; and Betty Grable knew her way around a French menu, inquiring about the “oefs [sic] plat au jambon: ‘What’s the idea of putting ham and eggs on the French menu?’” Music editor Len Engel recalled that each department had its own table.

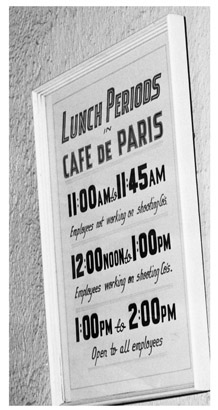

During the lot expansion of 1936, Darryl Zanuck also expanded the Café with a two-story addition at the south end, increasing the footprint of the building by about a third, and allowing for five hundred diners at a time. The main entrance was moved to its current location in the middle of the building. The entrance door, however, was on the right wall at the top of the stairs, where the door now leads to the Commissary Grill. The wood-and-glass doors that lead to the main dining room were installed much later. Inside there was a large cashier counter that sold a wide variety of cigars, cigarettes—smoking was permitted in the dining room until 1993—and candy. A large guest-book was also maintained there that diners were asked to sign. This is where hostess Juanita Brown greeted guests for decades. Behind the counter was a coat and hat rack, currently an opening to the casual seating section.

Two new private dining rooms were also added. What is now the casual dining area with big-screen TVs was originally the “Gold Room,” reserved for directors, producers, and top talent. The north wall was enclosed and accessed by French doors in the east wall (now gone). The Gold Room’s position made the south end of the Café the most sought-after place to be seated. Howard Hughes occasionally dined in the Gold Room, where he could watch for new conquests among the young actresses.

The second private dining room was built for Darryl Zanuck on the east side of the main dining room, directly across from the Gold Room. There was also a private patio surrounded by foliage. Both are still there and used by top executives. This private dining room was updated in the 1990s with sleek, modern, dark-wood paneling and a mural depicting the career of Rupert Murdoch. The second-story addition contained men’s and women’s restrooms and a private, three-room apartment for Nick Janios. This was rumored to be a secret rendezvous for Nick’s friends for many years. It currently serves as the administrative offices of the commissary.

“Ah, the commissary!” recalled Audrey Dalton. “An actor’s day is not only on the set, but in those days you were still ‘on’ at lunchtime. When lunch was called on the set, your makeup man, and they were always men then, warned you about touching your face and disturbing your makeup, but the hairdresser, perhaps because she was a woman, knew the importance of lunch in the commissary, possibly to your career. After all, the producers and directors also ate there and every actor was on show. In preparation an actress’s hair would be beautifully wrapped in mulleen, a very soft, silky, white netting fabric, creating a very flattering turban to hold your hair in place. So you sallied forth to the commissary, makeup perfect, hair covered with the beautiful wrapping, and still in costume. Now the hostess in charge of the dining room seated you according to her private grading of your importance, whether she recognized you, or who accompanied you, and your appearance. And it was always done in the most gracious way. Service was very good, as nearly everyone there was working on set.”

In the 1940s the white linen disappeared in favor of service on the bare wood tables edged with an aluminum trim. The original light fixtures were removed circa late 1946 in favor of “modern” fluorescent lights.

In front of the Café Richard Zanuck peddled the Saturday Evening Post at age nine for ten cents. It was his first job at the studio. When he showed his father the $85 he had earned that first day, Darryl questioned how he had managed it. He admitted he had accepted tips—a practice his father stopped. Undeterred, Richard employed his classmates from Pacific Palisades Grammar School to help him. By the time he was in the sixth grade he was reading scripts so that his father could get “a youngster’s opinion.” During his college years, Richard took jobs at the studio every summer working on the labor gang, constructing sets, working in the cutting room, and reading scripts in the story department. There he met his future partner, David Brown. Richard also wrote press releases in the Fox publicity department under the supervision of Harry Brand. He continued to work his way up from advertising in New York to his father’s assistant in Paris.

Over the years the Café was visited by US presidents Franklin Delano Roosevelt, Harry Truman, John F. Kennedy, Richard Nixon, and Gerald R. Ford. The Shah of Iran and his queen; Prince Philip of Greece; Haile Selassie, Lion of Judah; Prince Charles of Great Britain; President Sukarno of Indonesia; the King and Queen of Greece; and King Saud of Arabia have also visited.

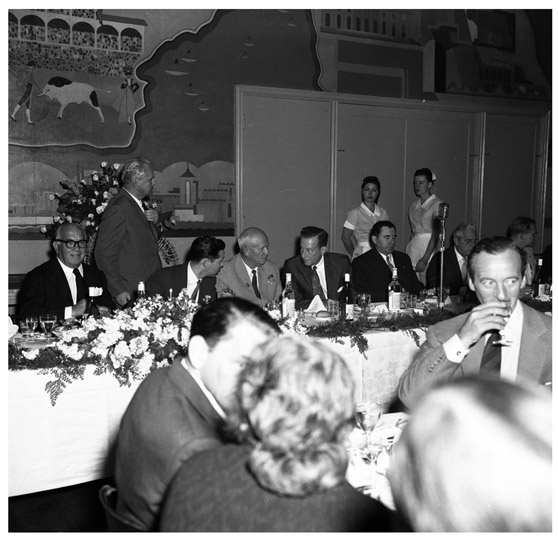

To date, however, the starriest event that ever took place here occurred on September 19, 1959, when Nikita Khrushchev—denied admittance to Disneyland—was honored with a luncheon at the Café. Four hundred and five VIPs attended, including Frank Sinatra, Bob Hope (Mrs. Khrushchev sat between them), and even the reclusive Marilyn Monroe. “You didn’t [typically] see Jennifer Jones or Marilyn Monroe around the commissary,” recalled David Brown.

The Studio Store in 2015 (left) and in 2016 (right).

It all came to an abrupt end when the commissary was shut down as the studio ran into financial troubles in the early 1960s.

Richard Zanuck recalled that the remaining employees ate in the electricians’ shed. No one was happier than his father when the Café reopened—but not to everyone. Kim Hunter recalled that the actors made up for Planet of the Apes (1968) were offered free lunches at their makeup table if they stayed away. Jacqueline Bisset (in her first starring role) dined here in The Sweet Ride (1968) as an actress having lunch with a studio executive (Warren Stevens) and her lover, Michael Sarrazin (in “reel” and real life). She and Raquel Welch were the last major stars nurtured under the Zanuck regime.

View of the dining room looking northwest, 2015.

View of the dining room looking northwest, 1938.

Details of the fabulous mural by Haldane Douglas. Look for Will Rogers in Oklahoma, Shirley Temple in Hollywood, Warner Oland (as Charlie Chan) in Shanghai, Janet Gaynor in Honolulu, and Warner Baxter (as the Cisco Kid) in Madrid.

From serving intimate meals to VIPs to supplying lunch to a cast of thousands for the “When the Parade Passes By” musical number for Hello, Dolly! (1969)—12,000 sandwiches, 6,000 apples and pieces of cake, for ten hours—they could handle anything. The commissary also has a long-held tradition of offering special dishes named for its stars, proving you had “arrived.” There was the Henry King cocktail (half tomato juice, half clam juice) that competed with the commissary’s signature cocktail (half tomato juice, half sauerkraut juice), and two Tyrone Power salads (one, with cottage cheese and fresh fruit, and the other, similar to a Caesar, but without the garlic croutons, helpful for lovemaking scenes).

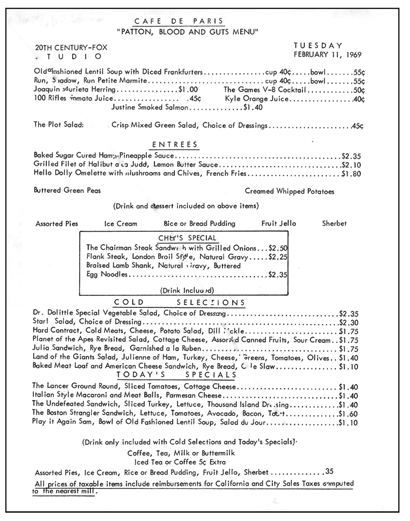

The tradition of meals named after current productions goes back at least as far as 1929, when “Sunnyside Up” Eggs were featured at Munchers. Other examples include the Valley of the Dolls Salad, the Flim-Flam Man Hamburger, A Guide to the Married Man Casserole, the Two for the Road Fruit Salad, the Boston Strangler Sandwich, the Butch Cassidy Grilled Filet of Halibut, the Hello, Dolly! Omelet, the M*A*S*H Bowl of Clam Chowder, and the Escape from the Planet of the Apes Roast Turkey Dinner. The Blood and Guts Minute Steak fortunately changed to the Patton Minute Steak when that film’s title changed. Another dud was Batman Ground Round.

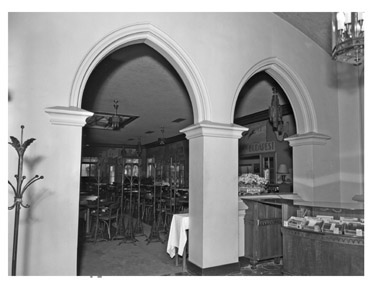

It was the end of an era when, again because of the studio’s troubles, the Café de Paris closed with Nick Janios’s retirement on February 5, 1971. There was even a plan to dismantle and auction the Douglas mural. Fortunately the mural was still there when the Café reopened, but as a cost-cutting measure food was served cafeteria-style by an outside catering service. Decorative arches from the set of Hello, Dolly! (1969) were added to guide patrons through the line.

Employees expressed dismay over the death of the old traditions. Burt Reynolds observed, “They wouldn’t dare name dishes after stars anymore either because they disappear so quickly.” Ed Hutson, who brought his mother [silent film star Eileen Sedgwick], Mrs. Merv Griffin, and Sybil Brand [wife of head of publicity Harry Brand] recalled that those veritable “ladies who lunch” were not pleased to have to stand in line and carry trays to their table when just a few years previously they had been given impeccable table service.

Fox’s vice president Bernie Barron remembers that these complaints brought about a complete refurbishment in 1976, which included both sit-down and cafeteria service. The outdoor deck on the south side was built, and the walls of the Gold Room were reconfigured and lined with mirrors to offer a casual dining room for the cafeteria line. Decorative planters were placed to delineate it from the formal sit-down dining area in the main room. Air-conditioning was installed for the first time, and 1970s fluorescent lights replaced the ones from the 1940s. Some large square banquettes with potted palms in the center were installed. The original 1929 chairs were stripped and stained in natural wood tones. Soon daily patronage numbers jumped from 250 back to 1,100. Beer and wine was also made available at lunch for the first time; previously, alcohol was only served on special occasions. However, even more exciting than the availability of booze (if the coverage in the employee newsletter is any indication) was the addition of frozen yogurt to the menu.

In the summer of 1984 the dining room was redecorated with new tables, chairs, carpeting, and dinnerware featuring the new Twentieth Century Fox logo. In 1986 another redecoration returned the dining room to its former Art Deco splendor. The fluorescent lights were removed and, although the original lighting fixtures could not be located, some vintage chandeliers were installed that were very much in line with the original decor. New kelly-green carpet and modern bentwood chairs with matching green upholstery were added as well.

More of the original portraits on the café mural that have since been painted over. From top left: Eddie Cantor, Arline Judge, Rochelle Hudson, Frances Drake, Don Ameche, Alice Faye, Jean Hersholt, Sonja Henie; second row: Tyrone Power, Simone Simon, Tony Martin, Claire Trevor, Loretta Young, Gloria Stuart, Michael Whalen; third row: June Lang and Victor McLaglen, 1938.

The cafeteria as it looked in 2015.

The Café de Paris during construction. The new addition expanded the main dining room by a third.

Looking into the exclusive Gold Room that was created during the addition. A tour of the United States was added to the expanded mural, 1938.

The south end of the dining room, 1938. The mural on this wall appears to be part of the original 1932 mural since it fits in geographically with the world tour theme and was kept on the south wall after the expansion of the east and west walls.

A new entrance was created with the new addition in 1936 and remained like this until the 1970s. You would enter through the door on the right (with bars) and exit through the one on the left.

Closeup of the sign as it appeared on October 31, 1951. Crowds were segregated by whether or not they were working on “shooting companies.”

The cigarette counter, 1938.

Warner Baxter pays his bill to cashier Helen Walker, 1936.

Matchbooks.

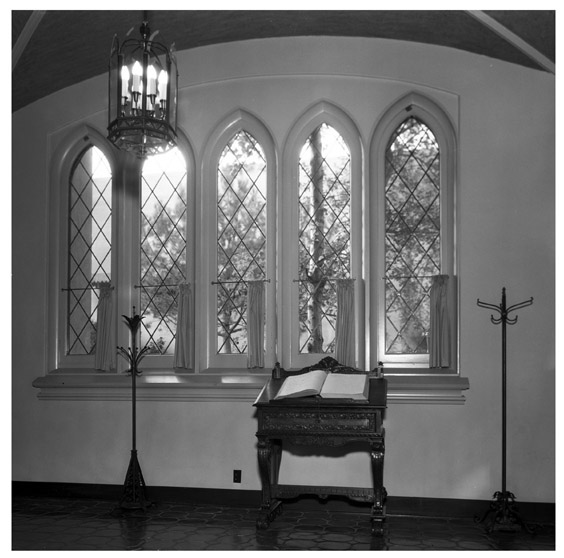

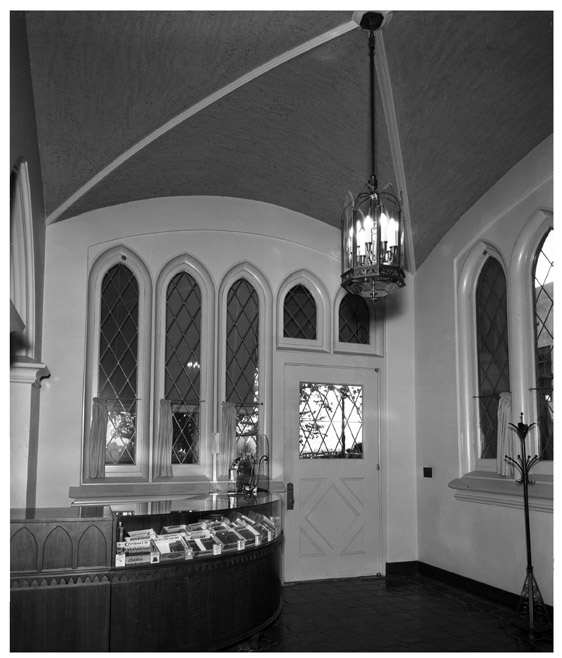

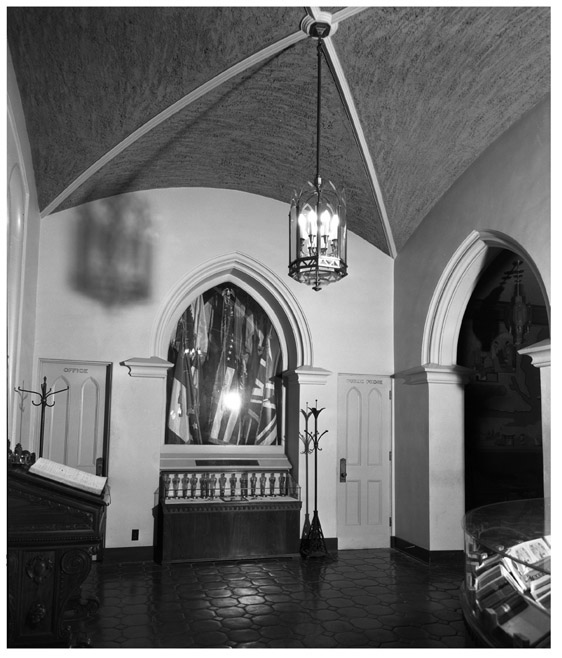

As part of the mid-1980s renovations, the north foyer that existed beyond the double Gothic arches was demolished to make way for the Fox Plaza parking garage. The small chapel-like vestibule, with a vaulted ceiling and elaborate stained-glass windows, had been added in the early 1930s to provide an additional entrance and cashier counter for the Café, as well as access to Nick Janios’s office and a telephone booth located just off the foyer.

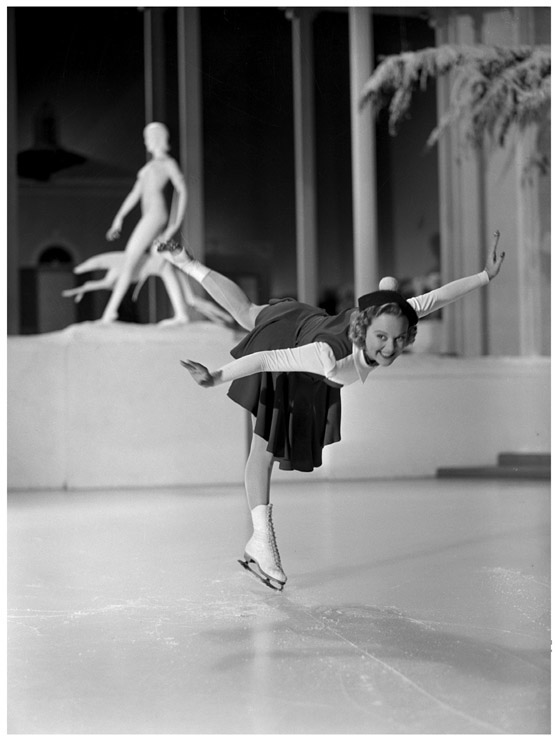

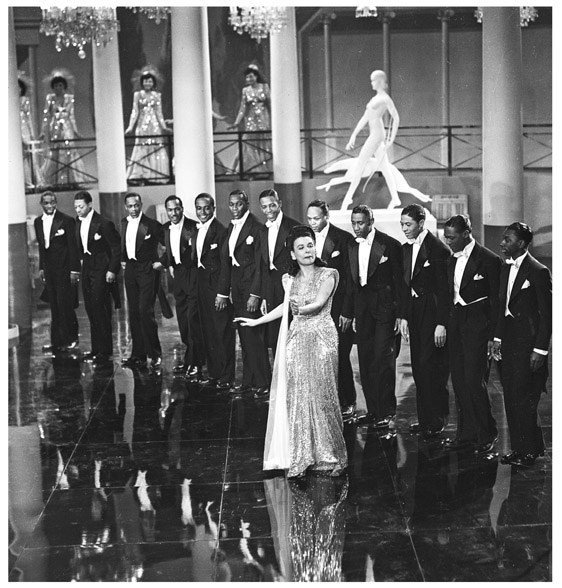

It was here that the Studio Store had its beginnings in 1976. It later moved to a trailer south of Bldg. 86 from 1984–86 before moving to its present location. The two open arches were filled in to become a solid wall. The sleek Diana, the Huntress, a statue from the prop collection that graced numerous films (Sing Baby, Sing (1936), Everything Happens at Night (1939), Second Fiddle (1939), The Gang’s All Here (1943), Stormy Weather (1943), Quiet Please, Murder (1943), and The Dark Corner (1946)), and then the dining room, was duplicated so there would be one for each alcove.

Although it is impossible to guess just how many actors were cast in roles because they were seen in the commissary, Samuel Fuller remembered choosing Jean Peters for Pickup on South Street (1953) while dining with Jeanne Crain, and Tom Mankiewicz wanted Lionel Stander for Hart to Hart (1979–84) when he saw him waiting for a table.

As with the rest of the company, Barry Diller was responsible for improvements here. In May of 1988 the studio took back management of the commissary from ARA Services, and its personnel were once again Fox employees. In 1990 he approved an enhanced menu with a category for “junk food”—including a foot-long Lasorda Dog (Fox owned the Los Angeles Dodgers from 1997–2004, and Tommy Lasorda was their manager) and the Fluffer Nutter, a peanut-butter-and-marshmallow concoction—as well as more health-conscious fare with a calorie count.

The commissary was in need of another makeover by 2013. Structural upgrades and repairs were executed, including replacing a portion of the floor that had warped due to the encroaching roots of trees against the foundation. When the floor-boards were torn up, the roots “looked like something out of Alien,” noted one observer. The interior was redecorated in a new color scheme of deep browns—espresso and chocolate—with new checkered carpet and, most notably, new wood dining chairs with an urbane retro flair. This is only the fourth set of chairs to grace the dining room in its history. Restoration of the mural included installing additional lighting to highlight it. The work was completed by the beginning of 2014.

The northwest corner is now the exclusive one where executives like Rupert Murdoch or Jim Gianopulos sit when they don’t require the confines of a private dining room. The friendly staff and the studio’s Oscars and Emmys still greet you at the door. Beside the commissary, in place of the original small formal garden, is a lawn used for large film-crew seating and studio events, as well as filming. For example, it was used as the White House Rose Garden in 1600 Penn (2012), and Enlisted (2014) used it for “military drills.”

The cast of Berkeley Square (1933) dining in what is now the Shirley Temple Room.

In the early days a giant bronze bell, reputed to have tolled the outbreak of the revolution in Russia in 1917, before the studio acquired it, was placed beside the entrance. Today another bell that once hung in the steeple of the church on Tombstone Street sits across the street. Of course, Avenue D did not originally dead-end here; it used to continue to the north through the studio gate to cross the studio bridge (west of the modern Avenue of the Stars bridge), designed by Joseph Urban and dedicated by Shirley Temple in 1938, to access the back-lot. The bridge originally spanned a deep ravine until the late 1930s, when Olympic Boulevard was connected here to Santa Monica Boulevard.

The south end of the Shirley Temple Room, 1935. The etchings on the walls were made by Edouard Chimot as character concept art for the film Marie Galante (1934). They remained on the walls until at least the 1970s.

The Shirley Temple Room, 2015.

This quaint private dining room disappeared during the 1936 expansion.

Looking into the Gold Room, circa 1938.

Looking into the Gold Room, 2015.

Tyrone Power and Loretta Young are offered a menu by Nick Janios, 1939.

Dorothy McGuire and Cesar Romero, 1943.

Betty Grable gives her order, perhaps off the French menu.

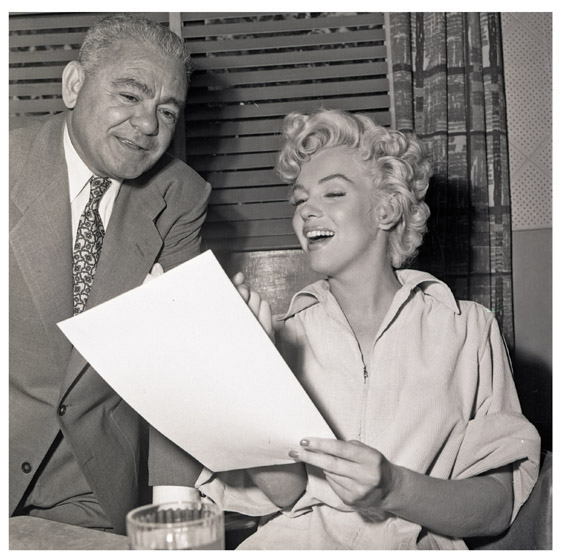

Nick Janios looks over the menu with Marilyn Monroe, 1954.

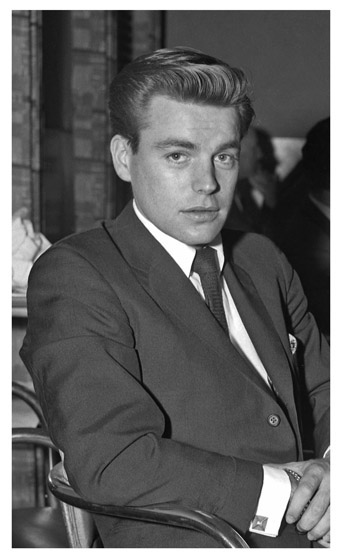

Robert Wagner, 1959.

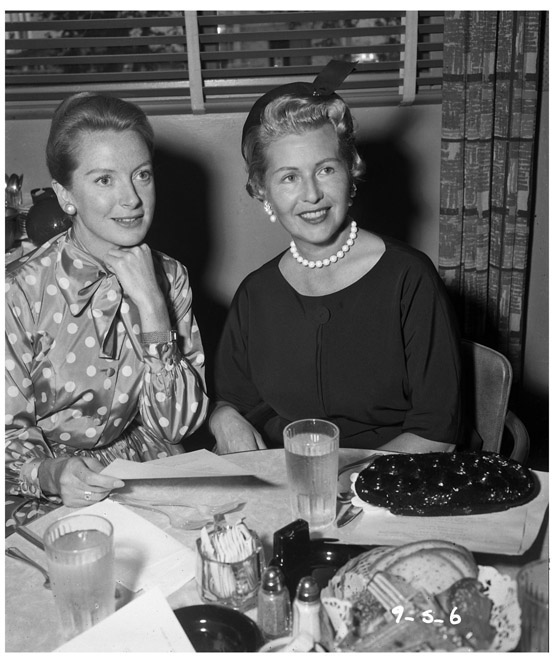

Deborah Kerr and columnist Sheilah Graham, 1959.

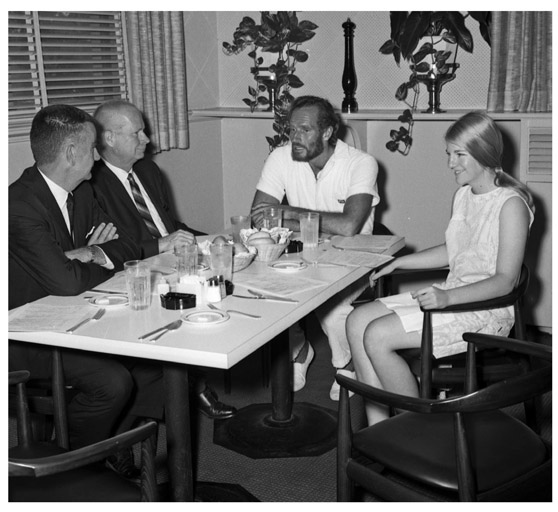

Charlton Heston, center, talks to members of the Associated Press about Planet of the Apes (1968).

View of the main dining room circa 1945.

View of the main dining room, 2015.

Alice Faye dines with Buck, the star of Call of the Wild (1935).

Carmen Miranda and friends.

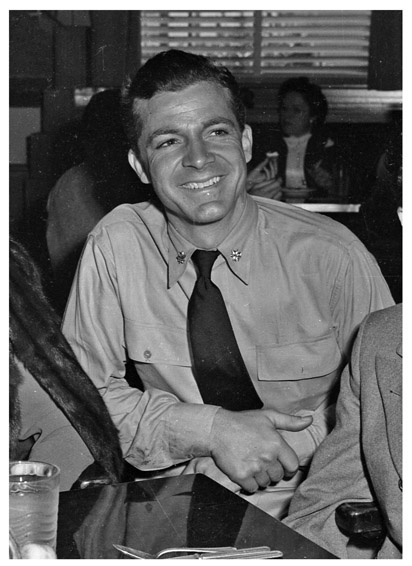

Dana Andrews.

Shirley Temple.

Gene Tierney and Linda Darnell, in costume for Brigham Young (1940).

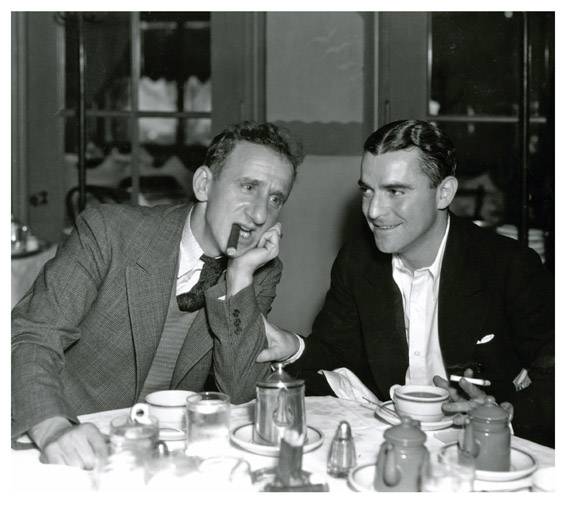

Jimmy Durante and George White.

John Sutton (left), in costume for My Gal Sal (1942), and Rita Hayworth lunch with a guest.

Richard Greene, left, and Wendy Barrie in costume for The Hound of the Baskervilles (1939).

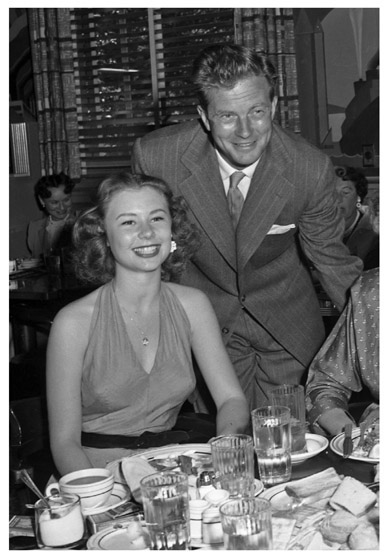

June Haver and Dan Dailey celebrating Dan’s birthday.

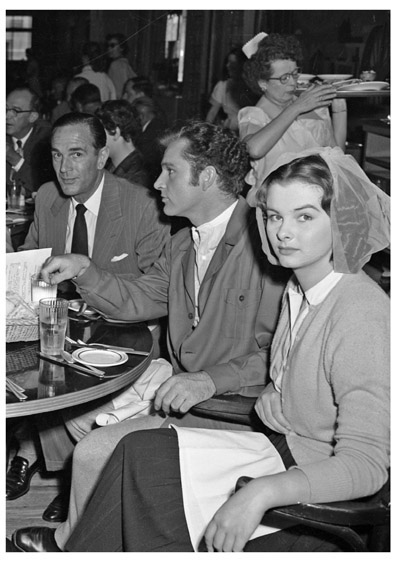

Maureen O’Hara (left) and Dick Haymes dine with a guest.

Richard Burton (center) and Audrey Dalton with hairdo for My Cousin Rachel (1952).

Mitzi Gaynor and William Lundigan.

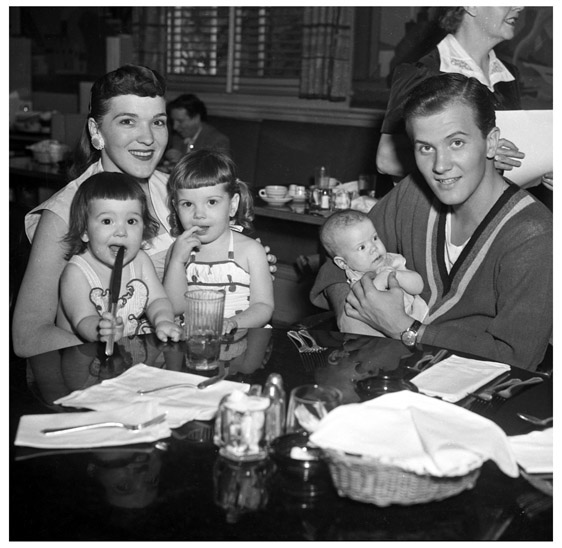

The Pat and Shirley Boone family. Pat is holding future pop singer Debby.

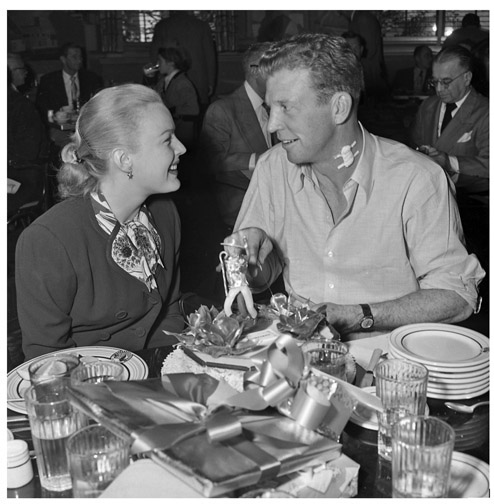

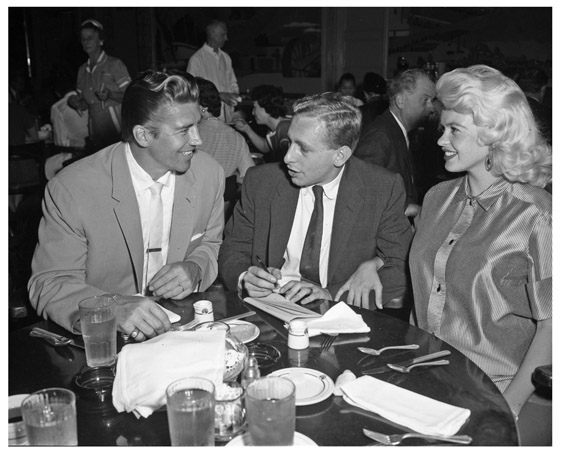

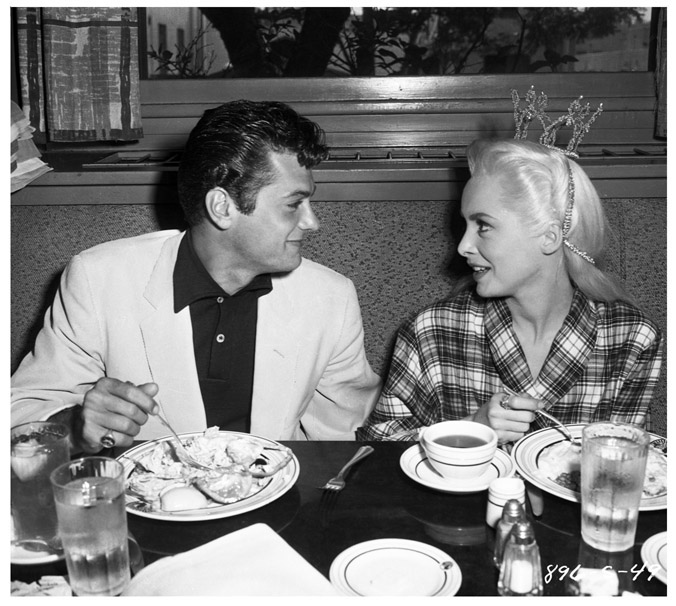

Mickey Hargitay (left) and Jayne Mansfield dine with a guest.

Tony Curtis and Janet Leigh in costume for Prince Valiant (1954).

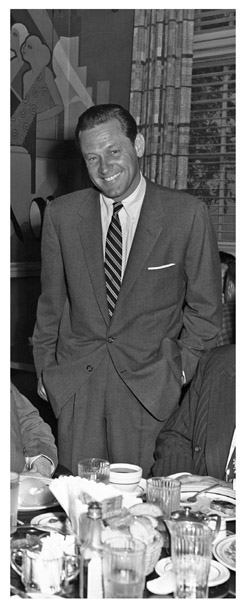

William Holden.

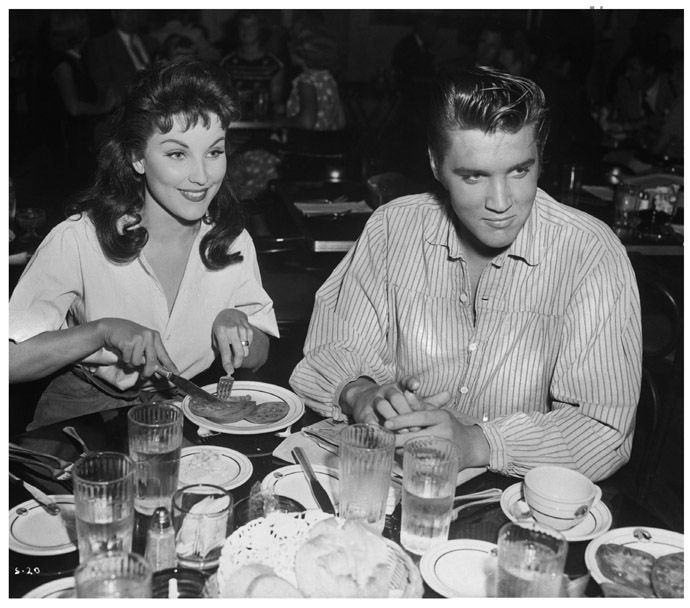

Debra Paget and Elvis Presley, in costume for Love Me Tender (1956).

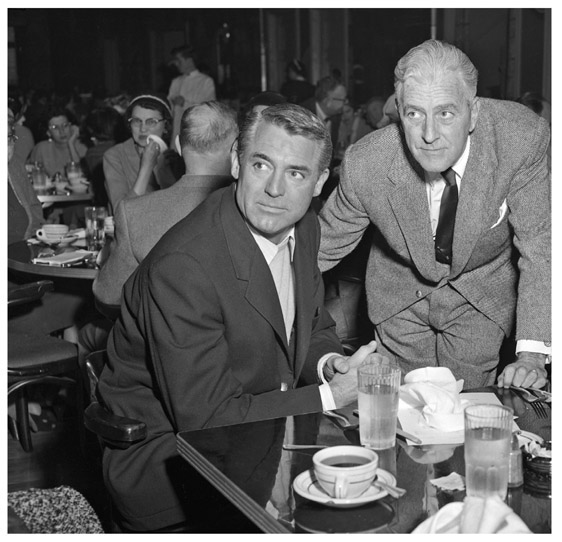

Cary Grant and Buddy Adler.

Shirley Jones surrounded by cast members from The Enemy Below (1957).

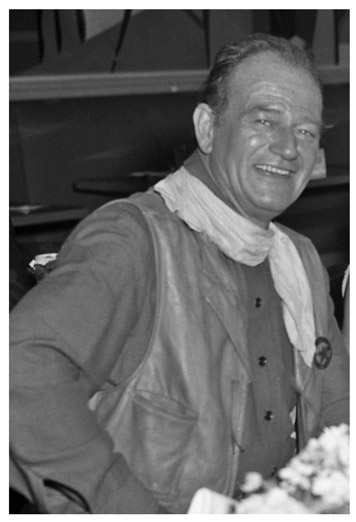

John Wayne in costume for The Comancheros (1961).

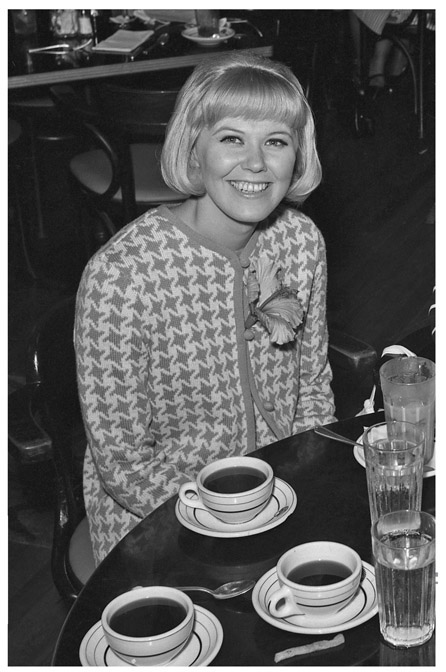

Doris Day.

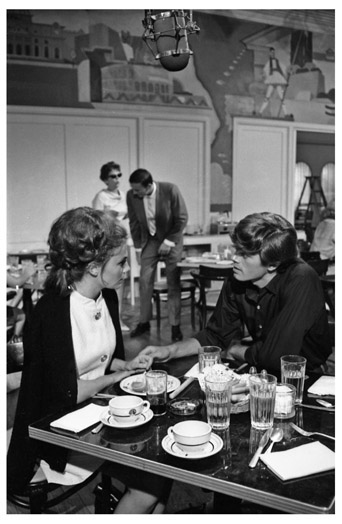

Mia Farrow and Barbara Rush.

View looking southwest circa 1962.

Soviet premier Nikita Krushchev was given the ultimate Hollywood welcome during his visit that culminated with a luncheon at the Café hosted by Spyros Skouras. Frank Sinatra and David Niven are in the foreground.

Jacqueline Bisset and Michael Sarrazin in a scene from The Sweet Ride (1968), one of only a few times the Commissary has appeared in a movie.

View looking southwest, 2015.

The menu, February 11, 1969.

The redecorated dining room, 1976.

One of these art deco pendants was found on the lot and several replicas were made to use in the main dining room to replace the fluorescent lighting that had been used for decades. This 1986 redecoration helped bring back the 1920s look to the room.

The Commissary Grill as it appeared in 2015.

This sleek statue of Diana, Roman goddess of the hunt, dating from the 1930s and a prop in several films, was put on display in the commissary in the 1970s. When the north foyer was razed and the portals filled, a twin was made to fill the opening. She originally had a bow but it has disappeared.

Diana appeared in the background of a couple of Sonja Henie’s films, including Second Fiddle (1939).

Diana is featured in this scene from Stormy Weather (1943), when Lena Horne performed “I Can’t Give You Anything But Love.”

Looking into the main dining room, this entrance was closed off when the north foyer was torn down in the 1980s.

For years, visitors were asked to sign the guestbook at the entrance, 1930s.

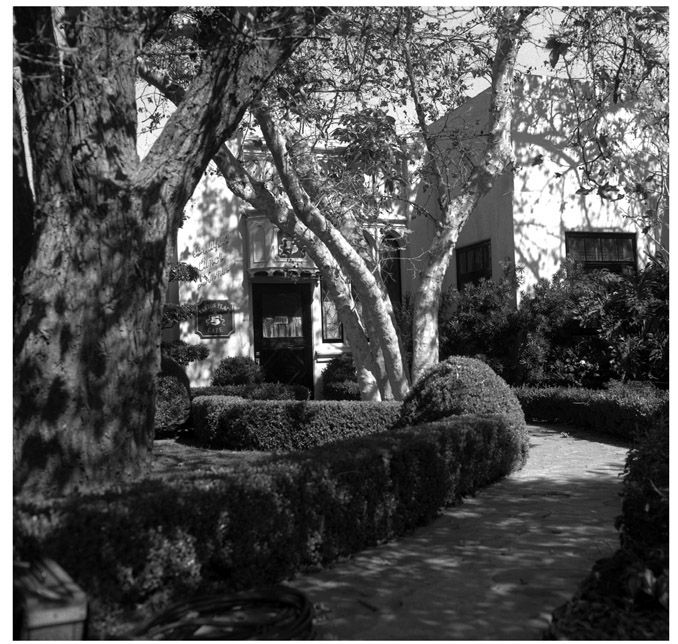

Exterior entrance to the north foyer. This served as the main entrance to the Café in the early-to-mid 1930s and was torn down to make way for the Fox Plaza parking structure. This picture is from the 1960s.

North foyer looking west. This became the main entrance for a few years in the 1930s.

The studio’s Oscars have always been—and still are—housed in the commissary. This was where the Studio Store first opened in the 1970s.

The studio’s Emmy collection, also on display as you enter, faces the Oscars, 2015.

The studio’s Best Picture Oscars proudly on display as you enter, 2015.

This executive dining room was remodeled in the late 1990s to include a mural depicting Rupert Murdoch’s career, and became known as the Rupert Murdoch dining room, 2015.

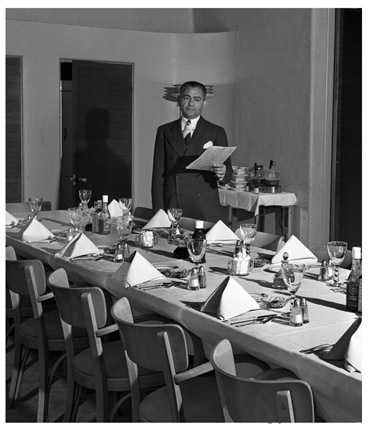

Photo of the Murdoch dining room, circa 1945, with Nick Janios standing ready to serve.

The dining room, 2015. The doors lead into the studio store.