“In The Last Golden Days of the Studio System” (1960–1965)

THAT’S OUR MIRACLE PICTURE.

DARRYL ZANUCK

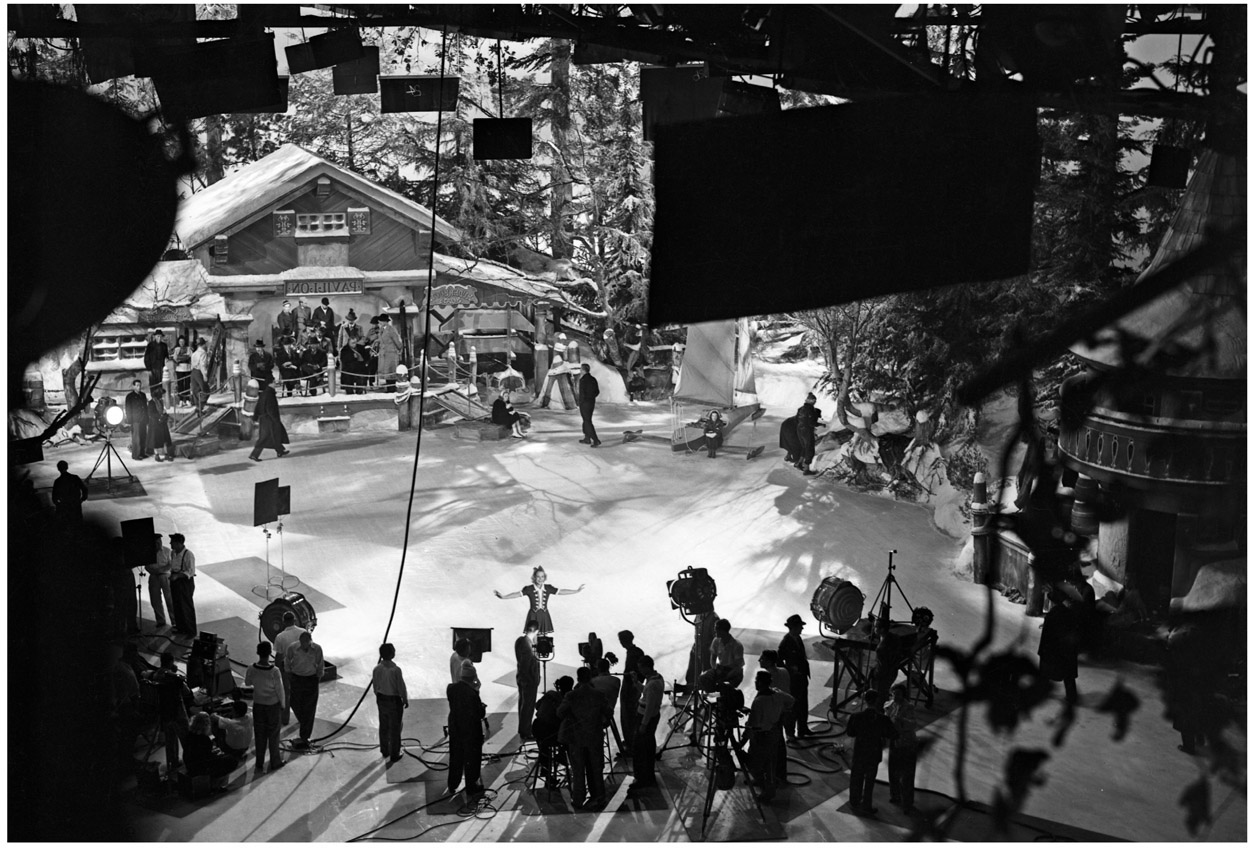

Seven months after Richard Rodgers and Oscar Hammerstein’s last Broadway musical, The Sound of Music, opened on November 16, 1959, Spyros Skouras approved the lease of screen rights for 15 years at $1.25 million, the largest amount yet spent on a literary property. He is a firm believer in bringing such stories of faith, hope, and family—in this case a true one of the von Trapp family—to the screen.

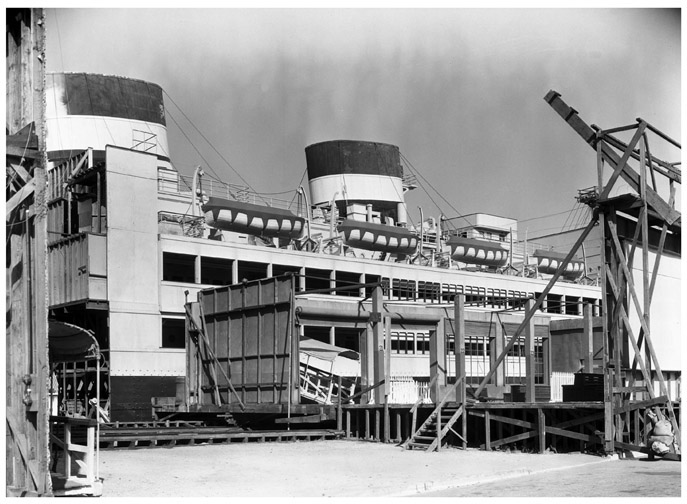

When Darryl Zanuck takes back control of the beleaguered studio and Bldg. 88 he announces on December 10, 1962, that the The Sound of Music is finally under way with his signing of Ernest Lehman to prepare the screenplay and a budget of $5.5 million. It is a brave declaration that Twentieth Century Fox is not through, and in fact capable of producing a major musical. Lehman writes the screenplay in his suite in Bldg. 80. It is completed by March 20, 1964.

Child star Angela Cartwright tests for the role of Brigitta. Fox would be her home for the next few years as one of the stars of Lost in Space (1965-68) which was filmed on the lot.

Rehearsing the choreography for “So Long, Farewell” by Dee Dee Wood (in white, back to camera) and Marc Breaux (at piano), with stand-ins for Julie Andrews and Christopher Plummer.

Rehearsing the choreography for the mountaintop portion of “Do-Re-Mi.”

When he is assigned as director and producer in October of 1963, Robert Wise joins a production team already assembled in Bldg. 78, including supervising, including supervising production designer Boris Leven; Roger Edens, who blocks out the musical numbers, including the spectacular opening sequence; and Irwin Kostal (music director) and Saul Chaplin (associate producer), attending to the music. Although Darryl Zanuck champions Doris Day for the role of Maria von Trapp, director Robert Wise and screenwriter Ernest Lehman choose Julie Andrews in November of 1963, and sign her to a two-picture deal. Christopher Plummer is cast as Captain von Trapp, Eleanor Parker as the Baroness, and Richard Haydn as Uncle Max.

The cast practices their bicycling on the lot for the “Do-Re-Me” sequence. From left to right: Angela Cartwright, Nicholas Hammond, Charmian Carr, Marc Breaux, Duane Chase, and Debbie Turner. The Century City condominiums rising in the background are at the corner of the Avenue of the Stars and Pico Boulevard.

Art director Boris Leven’s team includes assistant art director Harry Kemm, L. B. Abbott, and Emil Kosa Jr. in charge of visual effects, and set decorators Ruby Levitt and Walter M. Scott. Maurice “Zuby” Zuberano is employed by Robert Wise to create the film’s storyboards in ten weeks that can be used for reference throughout production.

On Wednesday, December 11, 1963, Julie Andrews makes her first appearance on the lot as the star of the picture when she is invited by Robert Wise and studio executives to lunch in the commissary.

On February 10, 1964, Charmian Carr (Liesl), the last of the seven von Trapp children to be cast, meets her screen siblings: Nicholas Hammond (Friedrich), Heather Menzies (Louisa), Duane Chase (Kurt), Angela Cartwright (Brigitta), Debbie Turner (Marta), and Kym Karath (Gretl) for the first time on Maria’s bedroom set on Stage Fifteen. for a regimen of photo tests and rehearsals, including dance lessons and biking around the lot in preparation for the “Do-Re-Mi” sequence.

The seven children’s voices are augmented by others on Stage One.

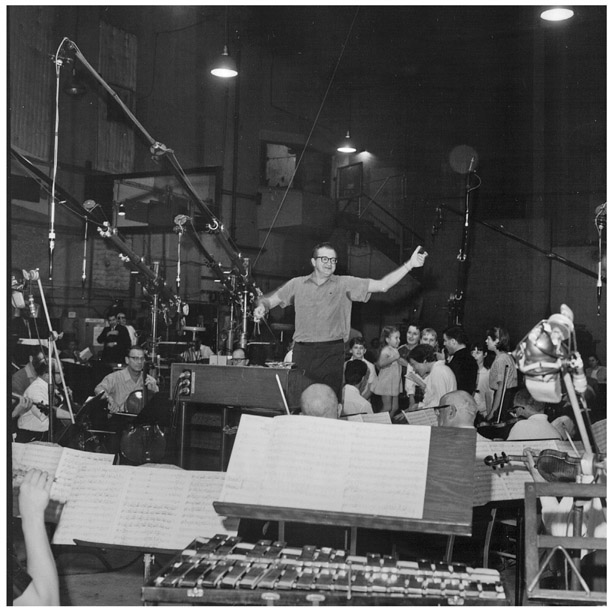

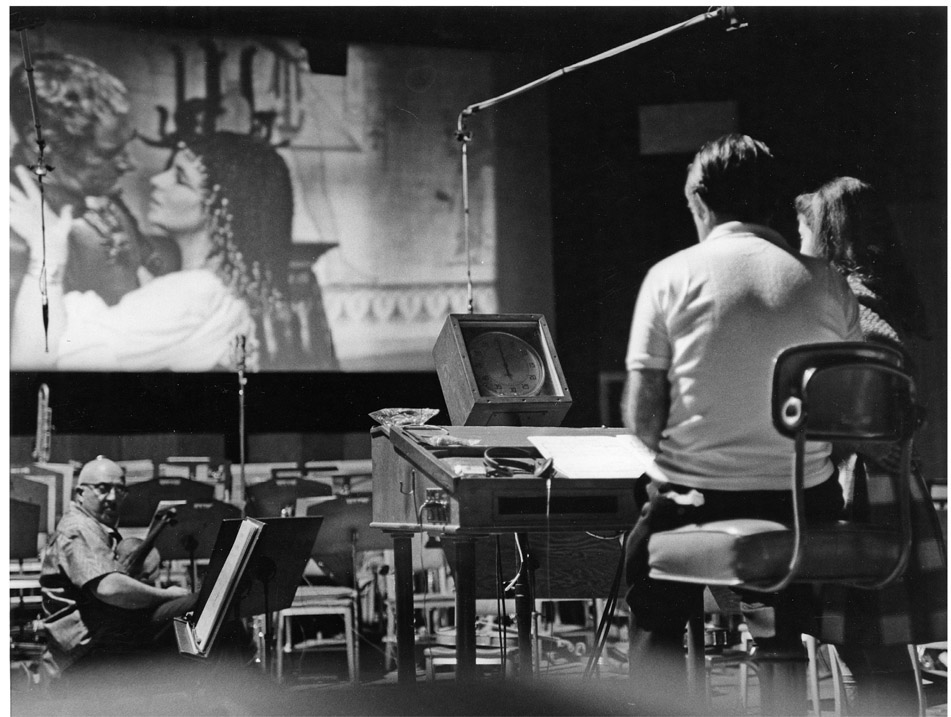

Irwin Kostal directs the scoring on Stage One.

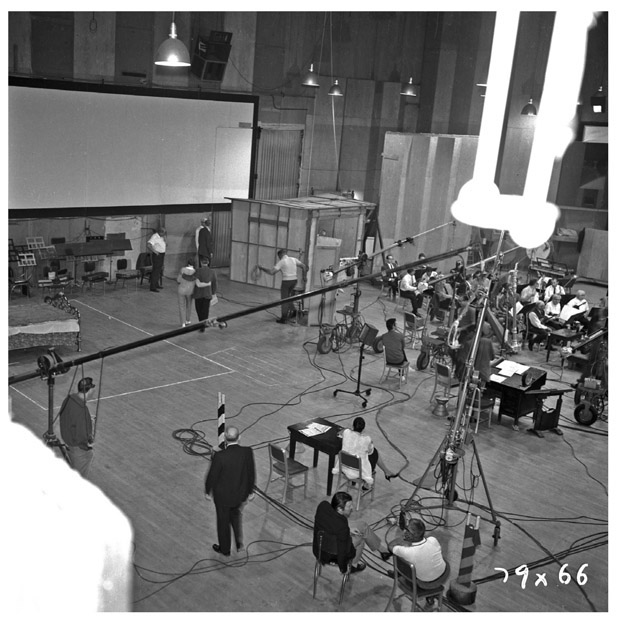

View of Stage One during music rehearsals. The large brass bed on the left was used for practicing “My Favorite Things.”

One of the costume fittings on stage. Angela Cartwright remembers “the amazing seamstresses that flitted around us shortening and adjusting each outfit like the fairy godmothers in Cinderella.”

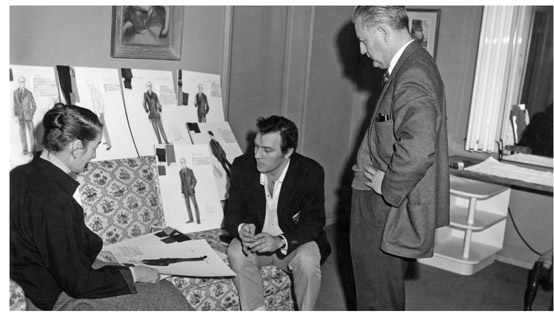

Costume designer Dorothy Jeakins, left, has a wardrobe conference with Christopher Plummer, middle, and director Robert Wise, right, in Plummer’s dressing room in Bldg. 86.

The children (except Carr and Karath) are schooled in Bldg. 80 for three hours a day by Frances Klamt, followed by shooting for no more than five hours a day.

Julie Andrews went in for hair and makeup tests in Bldg. 38, and remembers coming out with orange hair when efforts to heighten her natural blonde highlights went awry. Instead it was completely bleached blonde. Dan Truhitte (Rolfe) and Nicholas Hammond both had their hair dyed blond and had similar bad experiences. Hammond remembers what a painful process it was, while Truhitte claims his hair never grew back correctly.

Rehearsing the dining room sequence where Liesl sneaks out. Director Robert Wise is at the end of the table with his back to the camera.

Helping the actors is dialect coach Pamela Danova (training each with a mid-Atlantic accent), vocal supervisor Bobby Tucker, and choreographers Dee Dee Wood and Marc Breaux, whom Julie Andrews recommends after her happy experience with them on Mary Poppins (1964, Disney).

Even pajamas have to look perfect! Another costume test for “My Favorite Things.”

Marni Nixon, who dubbed other actresses for years, is finally cast onscreen as a singing nun. To strengthen the sound of the seven actors portraying the von Trapp children, four additional voices are used during the recordings on Stage One, including Charmian’s little sister Darleen. Margery MacKay, wife of the rehearsal pianist, performs the singing on the soundtrack for Peggy Wood (Mother Abbess). The scoring is supervised by Saul Chaplin and Irwin Kostal, and Kostal conducts the studio orchestra here the first week of November. Whether Christopher Plummer’s voice was going to be used on the soundtrack is debated.

The filming of “My Favorite Things.” Choreographer Marc Breaux stands at the foot of the bed.

Charmian Carr is wetted down for her entrance into Maria’s (Julie Andrews) bedroom set. An amused director, Robert Wise, stands behind her.

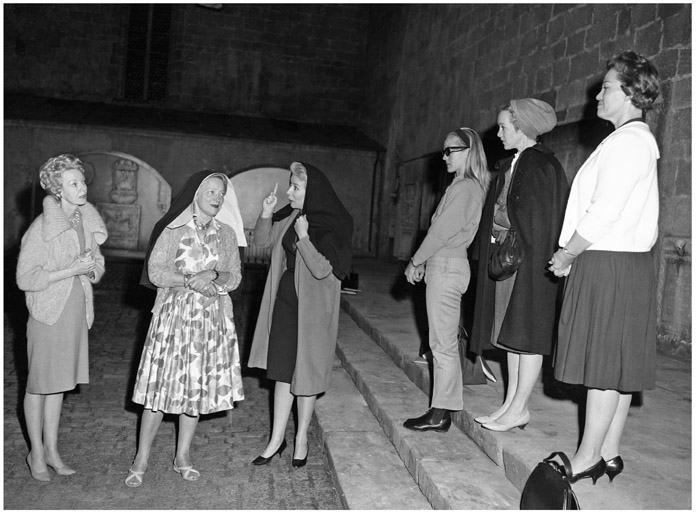

The nuns rehearse with Julie Andrews’ stand-in on the Nonnburg Abbey set..

The nuns, in their street clothes, trying to figure out how to solve a problem like Maria.

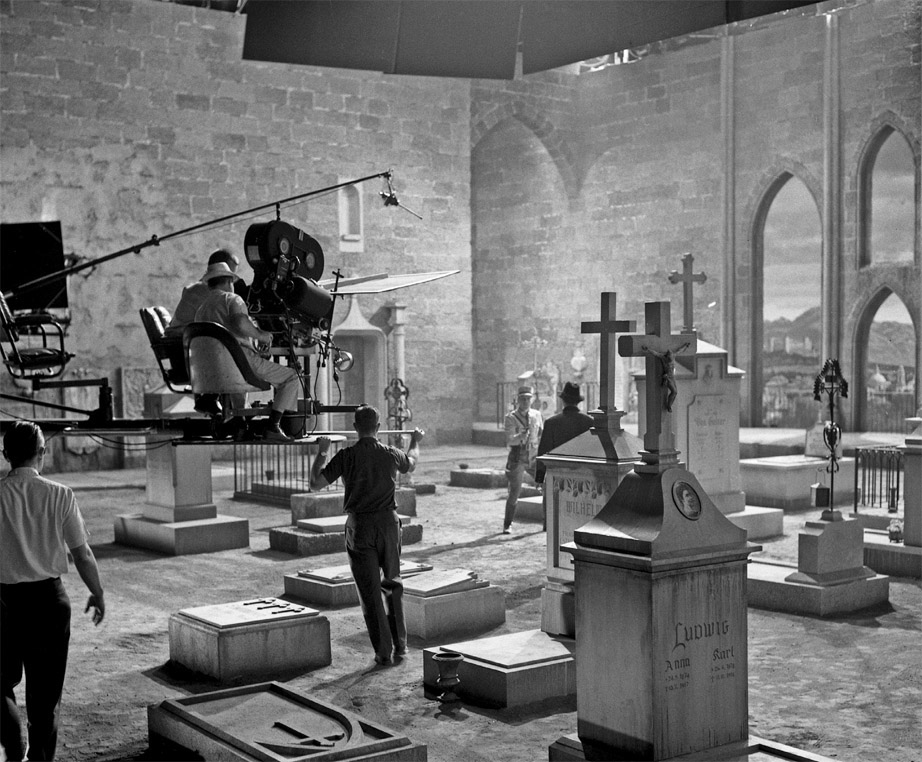

The extraordinary graveyard set of Nonnburg Abbey during the final confrontation between Captain von Trapp and Rolfe.

The blueprints for the von Trapp villa interior set built on Stage Fifteen.

Principal photography is green-lit in Bldg. 88 for Thursday, March 26, 1964. Richard Zanuck wires Robert Wise:

“Dear Bobby: Today we launch Sound of Music, which is the most important picture on our production schedule . . . I couldn’t have more confidence in the team of technicians and actors that we have assembled on Stage Fifteen for this picture, but my greatest satisfaction is that you are at the helm, and I am secure in knowing that we will have a great and monumental achievement.”

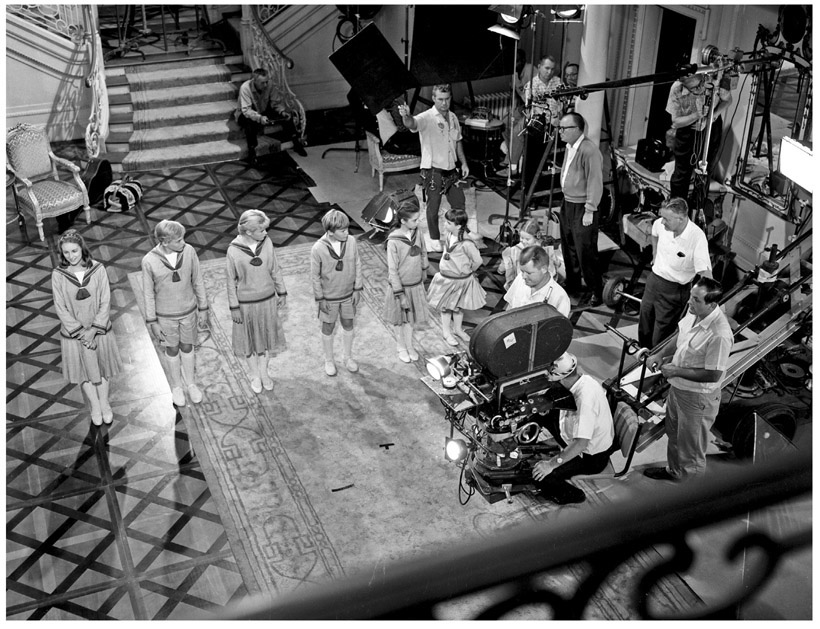

The von Trapp children prepare to introduce themselves to Fraulein Maria on Stage Fifteen.

Taking a lunch break. (From L-R) Duane Chase, Nicholas Hammond, Heather Menzies, Angela Cartwright, and Debbie Turner.

Principal photography begins at 10:36 a.m. on March 26, with Julie Andrews, Charmian Carr, and Norma Varden (Frau Schmidt) assembled here. The first scene shot was between Andrews and Varden. Then Carr made her film debut in the scene in which she climbs up to Maria’s room in a rainstorm. “My Favorite Things” is shot the following day, marking the acting debut of many of the children.

The wardrobe is designed by studio veteran Dorothy Jeakins. This is her favorite picture.

Since the Mother Abbess of the actual Nonnberg Abbey had refused to let the film company shoot inside, its exterior courtyard and interior room off the cloister are are recreated on Stage Sixteen. Filming begins in the Abbey cloister on April 2 with the nuns walking to chapel, chanting “Dixit Dominus.” Then “Maria” is filmed April 3–8, and the sequence where Julie Andrews and the nuns prepare for Maria’s wedding, on April 9.

Filming in the Abbey entrance room, Maria’s room, and outside hallway is done on April 9 on Stage Five, and in the graveyard set on Five on April 13–17.

Richard Zanuck writes Robert Wise on April 9, 1964:

“Dear Bobby: I can’t tell you how absolutely thrilled I’ve been by the footage you have been getting. As you know, we have four pictures shooting on the lot, and I run approximately forty minutes of dailies each day. Please don’t tell the other producers or directors, but I can hardly wait each day to get to your film, which I always run at the end. Each day it makes me more happy.”

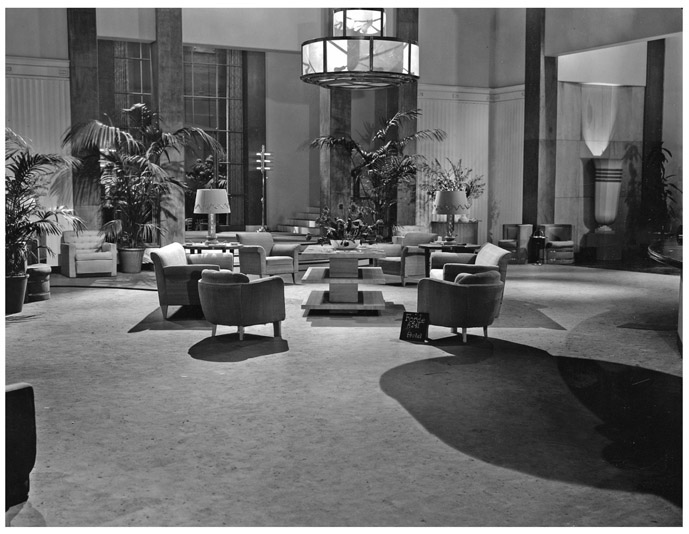

The von Trapp entry hall on Stage Fifteen.

Cast and crew depart for a planned six and a half weeks in Salzburg, Austria, for location filming that summer. Due to various problems—particularly the rainy weather—it takes eleven weeks. Meanwhile, Saul Chaplin and script supervisor Betty Levin fall in love and marry four years later. The real Maria von Trapp gets into the act, appearing in the background while Julie Andrews sings “I Have Confidence.” The sequence required thirty-seven takes, prompting her to declare: “Mr. Wise, I have just abandoned a lifelong ambition to work in the movies.”

Blueprints of elevations of the entry hall.

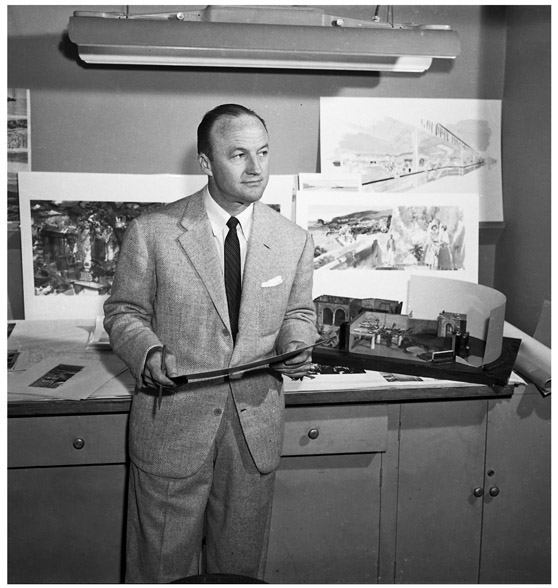

Art director Boris Leven stands in front of one of the most famous sets he ever designed in his long career in Hollywood.

Richard Haydn, as Max, stands in front of the gilt wall paneling during the party scene.

Blueprint of elevation of paneling in ballroom.

The ballroom and terrace of the von Trapp home set were on Stage Fifteen.

There is always a lot of standing around and waiting on a movie set!

Light check on the elegant Eleanor Parker as the Baroness.

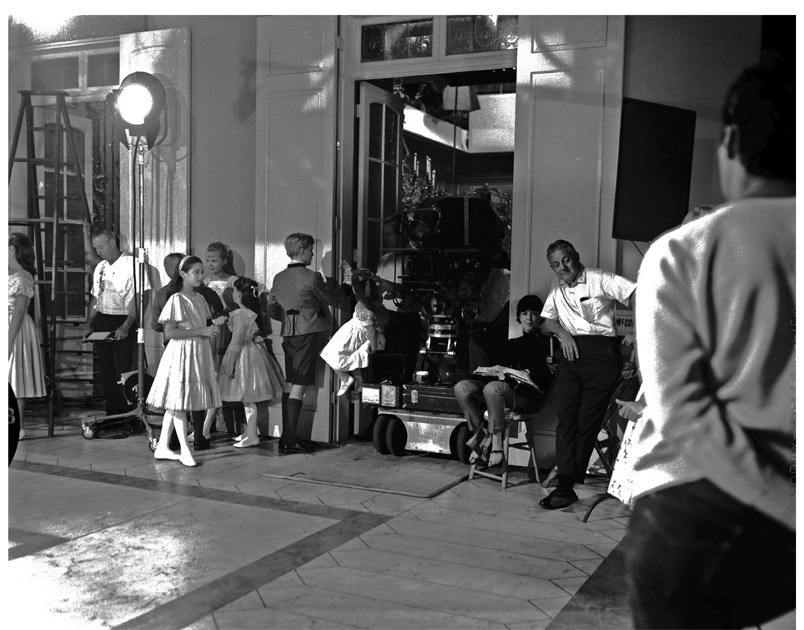

Filming on the lot begins again on Stage Fifteen on July 6, with the von Trapp family in the dining room of the new von Trapp villa sets, including the foyer and grand staircase set, and the ballroom, courtyard, terrace, dining room, and parlor. The party, “So Long, Farewell,” and “Laendler” musical sequences are filmed from July 15–24. On July 27 Eleanor Parker and Christopher Plummer have their final scene in the terrace set. On July 30 work begins on “The Lonely Goatherd” puppet show. After work here with the cast, the real puppeteers Bil and Cora Baird go to work on Stage Three with a second unit.

“So Long, Farewell” is performed on Stage Fifteen.

On August 6–7 the children sing “The Sound of Music” to their father, and the intimate family version of “Edelweiss” is performed in the parlor. On August 10 the last piece of the emotional sequence in which the von Trapp children sing “The Sound of Music” for their father is filmed, marking the last day the children all work together. They receive their own wrap party with cider-filled champagne glasses. The children are reunited on the lot on March 10, 1965, to dress for the Los Angeles premiere in their party clothes from the movie.

Angela Cartwright remained on the lot to make Lost in Space (1966–68), and later appeared in Room 222 (1969–74). Heather Menzies returned to guest star in S.W.A.T. (1975–76), starring Robert Urich. They dated for a year before Urich took her to a nearby restaurant and proposed. They were married until Urich’s death from cancer in 2002.

Look for the von Trapp grand hall in Do Not Disturb (1964), What a Way to Go! (1964), Way . . . Way Out (1966), Caprice (1967), The St. Valentine’s Day Massacre (1967), and Valley of the Dolls (1968).

Filming “The Lonely Goatherd.”

Shooting resumes on Stage Eight on August 11–13 for Julie Andrews and Christopher Plummer on a “green” set, re-creating the von Trapps’ garden and gazebo, shot at an estate in Salzburg called Schloss Leopoldskron, for the “Something Good” musical sequence. Robert Wise resorts to shooting them in silhouette when the couple cannot stop laughing over a noisy arc lamp.

The “Sixteen Going on Seventeen” musical sequence is filmed on Stage Eight on August 14–19. Cast and crew hold their breath when Charmian Carr goes crashing through a plate-glass wall of the gazebo during the dance because the wardrobe department failed to put rubber skids on the soles of her new shoes. She completes the sequence with a bandaged ankle. It is the last major scene filmed for the movie.

A publicity event on the steps of the Commissary to show off the marionettes created by Bill Baird (seen at far right). In true publicity style, the audience was contrived and consisted of the kids’ parents and Fox publicists!

When Liesl (Charmian Carr) ran out to the garden to meet Rolfe (Dan Truhitte) she had a long way to go—from Austria to Stage Eight where the “Sixteen Going on Seventeen” sequence was filmed.

Julie Andrews completes the “I Have Confidence” sequence filmed on location on a bus in front of a process screen on Stage Six on August 13. Principal photography ends, with more process work with Richard Haydn, Eleanor Parker, and Christopher Plummer in the Captain’s car, through September 1.

Liesl (Charmian Carr) meets up with Rolfe (Dan Truhitte) on Stage Eight for “Sixteen Going On Seventeen.”

Automated Dialogue Replacement (ADR) takes place here in the basement of Bldg. 226 from August 25 to September 8, when post-sync dubbing begins. “You always hope to use the original track,” said Wise, “but if there are interferences, you go back into the studio and you take a section, and you run it and run it, and then you redo the dialogue. It’s very time-consuming, and you have to be careful about the sync.” Christopher Plummer is allowed to sing his songs over two days after production-long efforts with voice coach Bobby Tucker. Everyone agrees his singing needs to be replaced, and Bill Lee is hired on October 1, 1964.

William Reynolds edits the film in Bldg. 32. The first major musical number to be completed is the “Do-Re-Mi” sequence that thrills cast and crew when they see it for the first time at a screening on the lot in August. The “rough cut” up to the “Do-Re-Mi” sequence is screened on September 18 for Richard Rodgers and his wife. The final rough cut of the picture is ready by October 2, 1964. Final edits take place on January 21, 1965. The final “answer print” from Technicolor and soundtrack is approved for release on February 5, 1965, at two hours and fifty-six minutes.

Filming “Sixteen Going on Seventeen.”

Christopher Plummer takes a break from a photo shoot outside of the Portrait Studio. The windows of the Commissary are seen on the left. The brick planter box still surrounds this tree in 2016.

One of the photos from the shoot.

On August 25–26, 1964, Julie Andrews, Christopher Plummer, Eleanor Parker, and the children had their formal portraits taken in Bldg. 58.

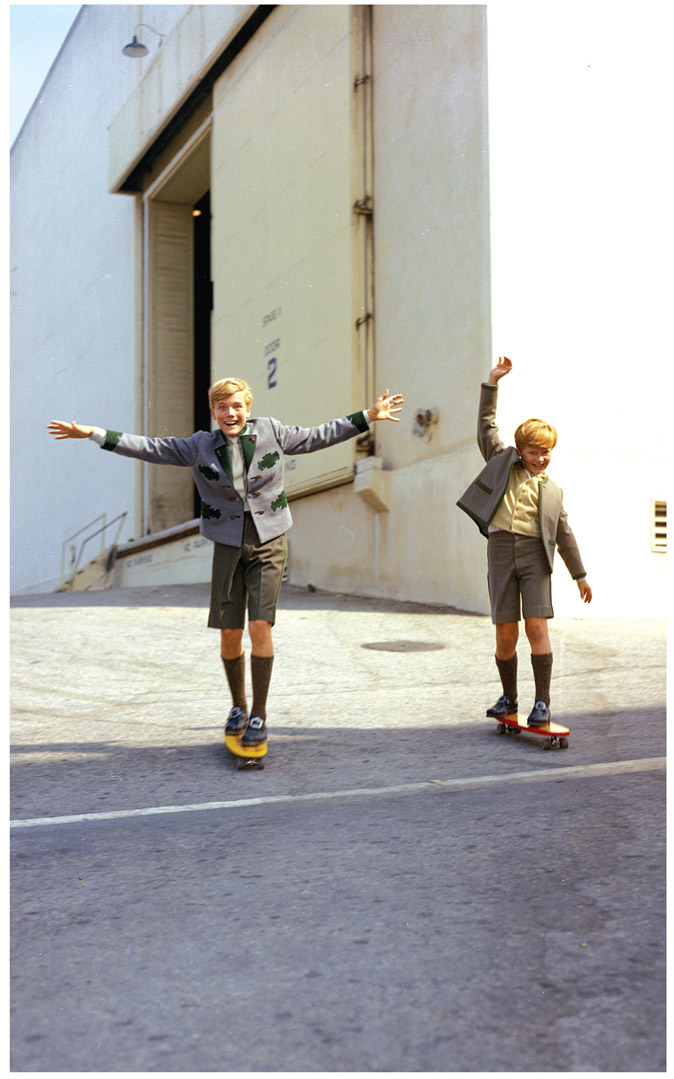

Nicholas Hammond, left, and Duane Chase, right, try skate-boarding in front of Stage Eleven.

The entry hall remained on Stage Fifteen for many years, and was used again in films like Do Not Disturb (1965) as a Paris hotel lobby.

As a Russian Embassy in Way...Way Out (1966).

As Sir Jason’s mansion in Caprice (1967).

As Al Capone’s home in The St. Valentine’s Day Massacre (1967).

As the main hall in the opening sequence of What a Way to Go! (1964).

As a fancy restaurant in Valley of the Dolls (1967).

Saul Chaplin and Irwin Kostal view the completed cut on October 5, 1964, and then prepare and supervise the scoring on Stage One. For two weeks—beginning October 16—Irwin Kostal arranges and orchestrates the background score. On November 2 scoring sessions begin. Veteran Buddy Cole passes away the day after completing his performance of the organ pieces for the score. Music editor Robert Mayer cuts and mixes the recordings. Murray Spivack is in charge of finalizing the six-track stereo magnetic master soundtrack, including sound effects. Chaplin supervised the creation of the soundtrack album. Released March 20, 1965, it reached Gold Record status and remains on the best-selling charts for 233 weeks. Combined with the sales and popularity of the original 1959 Broadway cast album, The Sound of Music remains the most popular musical score of all time.

In charge of the film’s publicity in Bldg. 88 is Mike Kaplan, who readies the advertising campaign for The Sound of Music beginning in February 1964, coming up with “The Happiest Sound in All the World” as its slogan. From its inception, the film is planned as one of the studio’s “road show” productions, treated like the opening of a major Broadway show. He also spearheads a campaign to win Academy Award recognition. The studio was free to release the film after the Broadway show ended its run after 1,443 performances, on June 15, 1963. The final print is readied for two previews in mid-January 1965.

The Sound of Music, at a final cost of $8.2 million, premiered on March 2, 1965, in New York, and then in 131 American theaters and 261 theaters overseas, becoming a now-legendary smash hit. Domestic rentals for 1965 neared the $115 million level, a new record for the company.

Three years later the Zanucks proudly declare that the studio is debt-free from the dark days of Cleopatra (1963). Ultimately the film runs for nearly five years in its first run—a record still never equaled. Its enormous profits encourage a third expansion of the Westwood lot in the southwest corner and along the eastern boundary of the studio east of Avenues B and C, including four new soundstages in 1965, two more in 1966, and the building of a number of sets, including a new $250,000 Western Street for Stagecoach, and Dolly Street for Hello, Dolly! (1969). The movie continues to inspire. After numerous theatrical reissues, Fox got $21.5 million in July of 1978 for a phenomenal twenty-two-year run for the film on NBC. It has since been released, and never out of print, in all the various home video formats. Critic Charles Champlin wrote: “The Sound of Music works because we still, more often than not, ask the movies to give shape to our dreams rather than our nightmares, to spell out our wishes and fancies instead of our fears, and The Sound of Music says with a towering clarity that there is still innocence in the world, that love conquers all and right will prevail.”

Kym Karath celebrates her sixth birthday in the schoolroom in Building 80 with the other cast members. Their teacher, Frances Klamt, and publicist Mike Kaplan also attend.

Besides the five Academy Awards and five nominations bestowed upon The Sound of Music in 1966, The Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences saluted the film’s fiftieth anniversary at their 2015 Oscar show. Of the film’s legacy Agathe, the eldest daughter of the von Trapp family, wrote in her 2004 memoir:

“The creators of The Sound of Music were true to the spirit of our family’s story. After meeting so many people over the years who told me how they had derived such great enjoyment and inspiration from the musical and the movie…is it not easy to see the hand of God in all this?”

Alice Faye exits the Portrait Studio in 1945.

BLDG. 58: THE PORTRAIT STUDIO (1929)

First in operation at the Western Avenue lot, the portrait studio was transferred here, where it remained until 1971. Almost every major star in Hollywood sat for portrait sittings here, since for most of the twentieth century the motion picture industry relied on print media for advertising its films. Glamour portraits, candids, and amusing novelty, holiday-themed art were standard fare. Actors and actresses on contract at Fox received special attention, with a portrait file (called a “Star-head”) dedicated solely to them.

Linda Darnell, with golden tresses for her role in Forever Amber (1947), get ready for a photo shoot with Gene Kornman (at right with glasses).

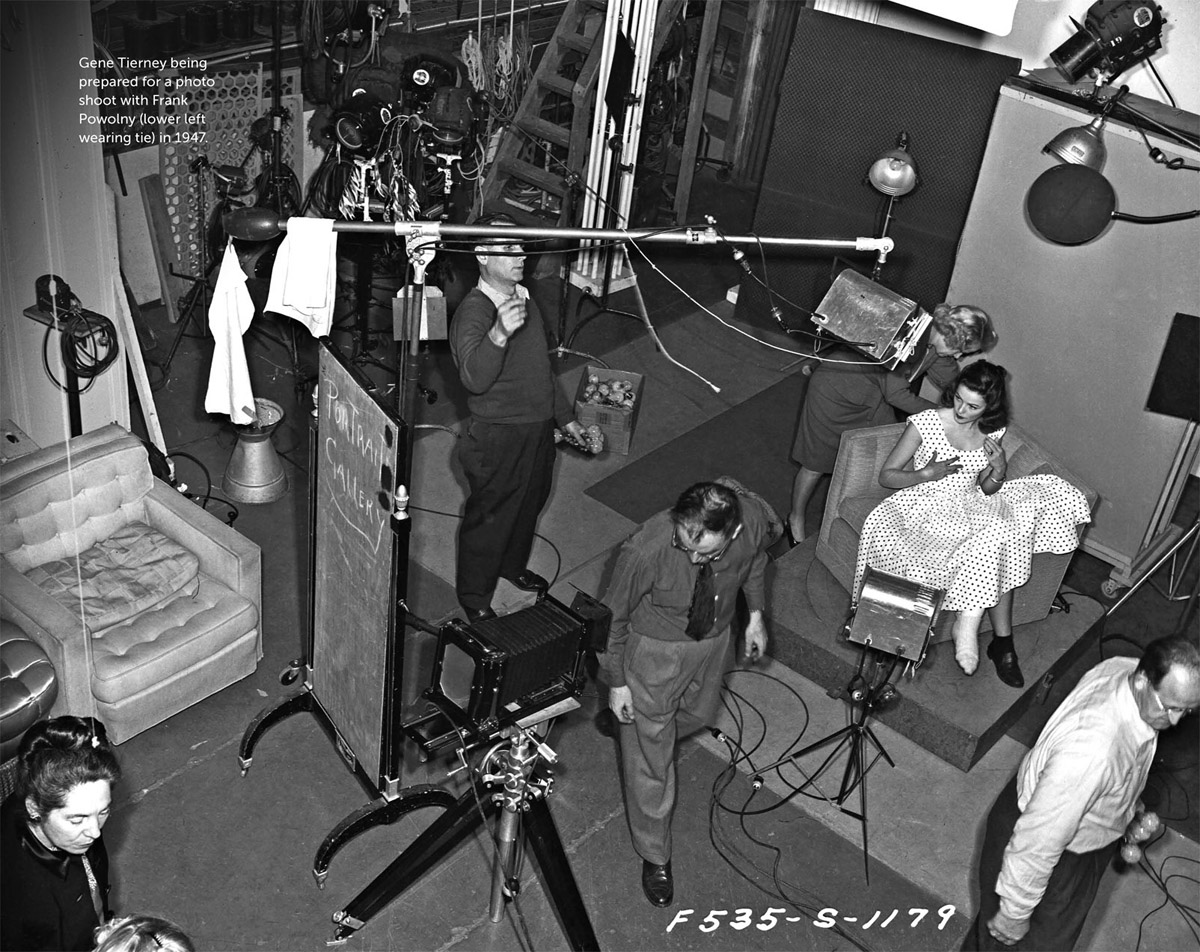

Take Gene Tierney, for example: When she arrived on the lot she was introduced to publicist Peggy McNaught, who, in short order, had photographers like Gene Kornman and Frank Powolny taking pictures of her everywhere, both on and off the lot, while promoting her for fashion layouts in magazines and newspapers. Each photo would then be marked with her own studio publicity number to keep track of the voluminous photography. Tierney’s Starhead file would ultimately reach 1,550 photographs—and that did not include any stills from her films.

Jeanne Crain strikes a glamorous pose in 1944.

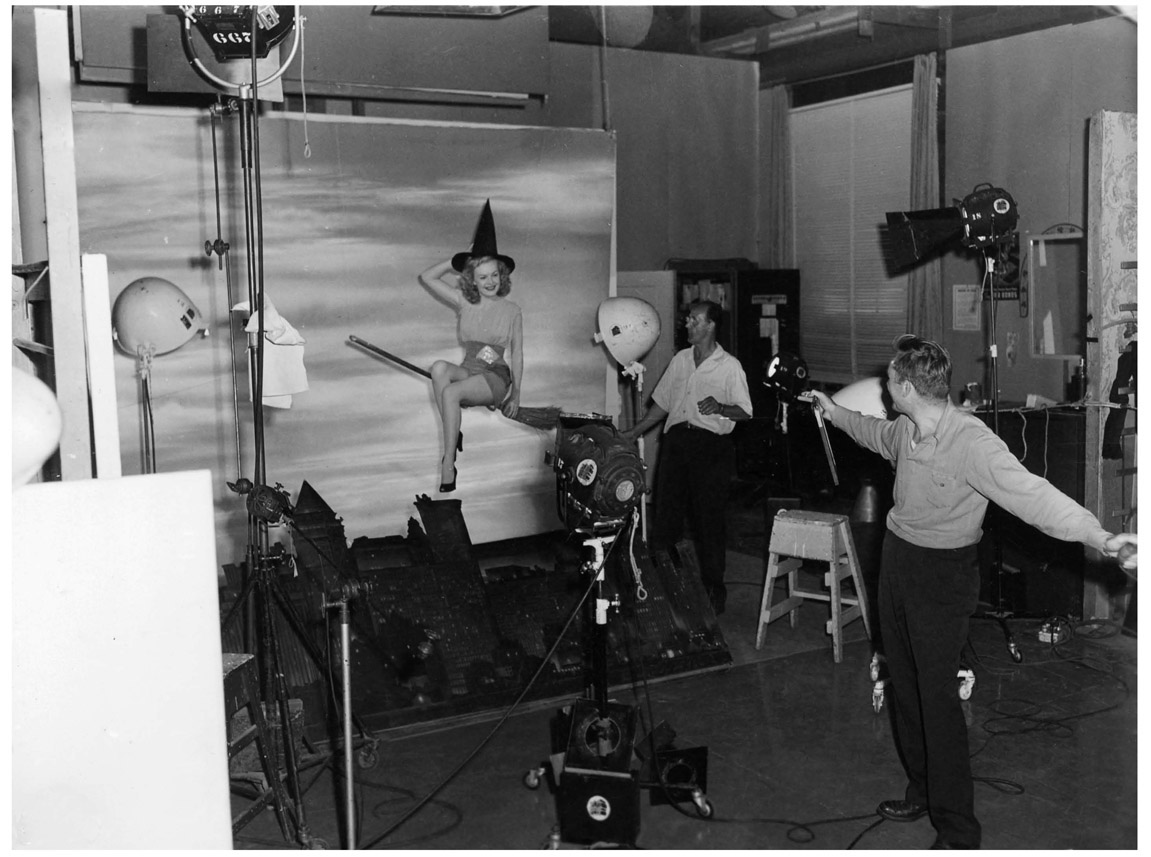

June Haver steadies herself for some campy Halloween photos, 1944.

Kornman, one of the leading still photographers in Hollywood, spent most of his career at Fox. He once estimated that he had taken over half a million photographs in the first twenty years of his career. Among his favorites was Shirley Temple, who came to Fox about the same time he did. She was primarily photographed (well over 7,500 portraits!) by Anthony Ugrin. Of course, the most famous photograph to originate from this lot, and this studio, was Betty Grable’s pinup shot, taken here in early 1943.

“We were making a picture called Sweet Rosie O’Grady at the time,” Grable recalled, “and in one scene an artist was to draw me for a cover on Police Gazette. He wanted the measurements and the figure just right, so I climbed into the tight bathing suit and posed for a bunch of pictures. Frank, as usual, wasn’t quite satisfied. Then he got the idea for the pose with me looking back over my shoulder. It never was really intended for publication, but when the boys in the publicity department saw it they had a few thousand prints made. Thanks to the servicemen overseas it turned out to be a pinup sensation, and it did a lot for me. But back of the picture was Mr. Powolny and his camera genius.”

At least ten million copies of the photo are estimated to have been distributed during World War II, and it remains the most reproduced movie still in history.

Powolny, who came to work at Fox in 1923, became a still photographer while working on John Ford’s The Three Bad Men (1926), and then moved into the portrait gallery due to the insistence of much-impressed Loretta Young. In 1956, after the Labor Day holiday weekend, Powolny received Elvis Presley here for his first photo session for the movies, and was impressed enough to note: “If I’m any judge, he’ll stay up there as long as Sinatra and Crosby have done.”

Joan Crawford poses in Henry Fonda’s arms for Daisy Kenyona (1947).

Instead of a staffed portrait studio, photographers are now hired on a per-picture contract basis. This building currently houses special effects and dry-cleaning services for employees. Look for the exterior and doorway to the portrait studio in Holiday for Lovers (1959) and Shock Treatment (1964).

This was apparently a tiresome photo session for Maureen O’Hara, Clifton Webb, and Robert Young, stars of Sitting Pretty (1948).

This is the earliest known print of the Betty Grable pin-up, the stamp on the back indicates that it was approved by the MPAA on February 17, 1943. Note the garter belt that has been retouched on Betty’s left leg. The photo was taken on a whim by Frank Powolny as part of a photo shoot to create props for Sweet Rosie O’Grady (1943).

Some of the photos from the photo shoot that produced the famous pin-up and the resulting illustrated props for the film.

Frank Powolny poses with an altered version of his most famous photograph at this retirement party in the Portrait Studio, 1966.

Sophia Loren made her English-speaking film debut in Boy on a Dolphin (1957) as a treasure-hunting sea diver. This photo got a lot of attention, and became one of the most popular pin-ups of the 1950s.

Similarly, Raquel Welch’s career got a huge boost after she appeared as Loana in this scrap leather bikini in One Million Years B.C. (1966).

Terry Moore’s infamous ermine swimsuit ensemble designed by Edith Head.

Just a few of the many thousands of faces that were photographed in the Portrait Studio: (top row, L-R) Myrna Loy, Marguerite Churchill, Una Merkel. Neil Hamilton and Elissa Landi, taken for The Woman in Room 13 (1932). (bottom row) Tyrone Power and Loretta Young, taken for Love is News (1937). Basil Rathbone, taken for The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes (1939), and Cesar Romero.

(Top row, L-R) Lena Horne, taken for Stormy Weather (1943), Laird Cregar, taken for Heaven Can Wait (1943), Anne Baxter, (bottom row) Dana Andrews, Carmen Miranda, taken for Week-End in Havana (1941),Bette Davis, taken for All About Eve (1950), and James Mason.

(Top row, L-R) Marilyn Monroe, Deborah Kerr, taken for The King and I (1956), Gregory Peck, taken for The Man in the Gray Flannel Suit (1956), (bottom row) Suzanne Pleshette, taken for Fate is the Hunter (1964), Diane Baker, Jeffrey Hunter, and Elvis Presley, taken for Flaming Star (1960).

Themed holiday photography was standard fare for decades. Here are a few examples from kitschy to lovely. (Top row, L-R) Natalie Wood, Janet Gaynor, John Wayne, Joan ollins,(bottom row) Shirley Jones, cast of The Sound of Music.

(Top row, L-R) Jayne Mansfield, Ann-Margret, Shirley Temple, Rita Moreno, (bottom row) Doris Day, Mitzi Gaynor, Debra Paget

BLDG. 58: MEN’S WARDROBE (1929)

Building 58 with the Commissary lawn in front. Building 59 is at the right. The rising staircase is part of the Galaxy Way parking structure

Rossano Brazzi gets measured for a suit for his role in South Pacific (1958).

“Does this hat go with this suit and shoes?” Men’s Wardrobe was a one-stop-shop for all sartorial needs. Note the rows of police and military badges on the wall, 1949.

Boots, boots, and more boots in Bldg. 58, 1950.

Marine, Army, Navy—you name it Fox had a uniform for it, 1949.

Interior of Bldg. 58 when it was the Men’s Wardrobe Department, 1936. When the building was converted to office space, the mezzanine was extended to create a full second floor, and the large windows on the left were replaced by smaller ones.

One challenging aspect of the wardrobe department is ensuring that the correct medals, badges, and insignias of anyone in uniform—from hotel bellhops to army generals—are correct.

Building 59 in 2007.

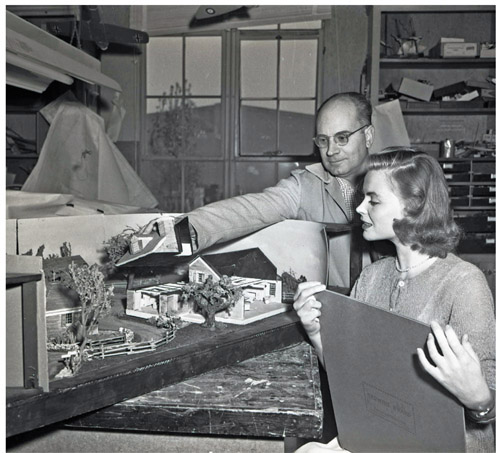

Original 1932 caption: “Alfred San-tell, himself, accompanied Marian Nixon to the large wardrobe at Movietone City where they spent all afternoon selecting the simple costumes Marian will wear in her forthcoming sound version of Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm (1932).

Building 59 circa 1937.

BLDG. 59: WOMEN’S WARDROBE (1929)

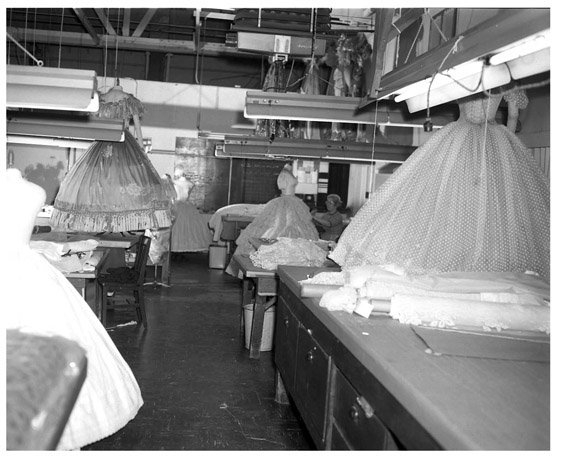

This was another of the departments during the years of the studio system that was part of the assembly line, and an assembly line in and of itself. There were salons where costume designers’ work was discussed, the back room constantly abuzz with sewing machines where the costumes were made, fitting rooms where the stars were dressed, and storage where costumes were carefully cataloged for reuse.

From the beginning Movietone City had the best under Rita Kaufman, including Earl Luick, Herschel McCoy, Rene Hubert, and Lewis Royer Hastings (“Royer”). The talented Sophie Wachner could create costumes from the most mundane, such as Irish peasants for Song O’ My Heart (1930), to the fantastic, for Just Imagine (1930).

CharlesLeMaire goes over sketches and fabric in his office, circa 1946.

After the merger Royer became head of the wardrobe department, and Gwen Wakeling, from Twentieth Century Pictures, was the studio’s head costume designer until 1942. Travis Banton succeeded as head of the department in 1940. Charles LeMaire, a veteran of the Broadway shows of Florenz Ziegfeld and George White, as well as the circus of John Ringling North, first showed up here at White’s request to design the costumes for George White’s Scandals (1934).

William Travilla stands with the mannequins for Sharon Tate, Judy Garland, Barbara Parkins, and Patty Duke for whom he created the wardrobe for Valley of the Dolls (1967).

Royer displays one of the studio’s creations for One in a Million (1936) in his office that also served as a fitting room. When facing the building on the outside, the windows in the picture are on the right of the main entrance.

Betty Grable tries out a new costume for Tin Pan Alley (1940) while costume designer Travis Banton sees how it compares to his original sketch.

LeMaire took over the department in 1943 upon his discharge from the army, agreeing to handle the additional work of designing for some of the studio’s pictures each year. He began with Billy Rose’s Diamond Horseshoe (1945), when producer Bill Perlberg heard he had worked with Rose. During his dazzling tenure he had Yvonne Wood and Helen Rose to design the trademark looks of Carmen Miranda; Bonnie Cashin, whose remarkable work began with Laura (1944); and Rene Hubert, for Forever Amber (1947), all of which showcased the department at its height.

Gene Tierney’s husband, designer Oleg Cassini, made a name for himself here (The Razor’s Edge, 1946, and The Ghost and Mrs. Muir, 1947), appearing as himself in Where the Sidewalk Ends (1950). In the 1950s—after Gregory Peck startled everyone by collapsing with a coronary during fittings for David and Bathsheba (1951)—LeMaire hired Edith Head to do All About Eve (1950). The notorious ermine bikini that got the Korean War’s number-one pinup Terry Moore sent home amid a blaze of publicity was also Head’s.

Rene Hubert discusses the costumes for Music in the Air (1934) with star Gloria Swanson who is wearing one of his creations for the film

Dorothy Jeakins, who designed costumes for everything from Niagara (1953) and Titanic (1953) to South Pacific (1958) and Young Frankenstein (1974), had a particular gift for making rich-looking wardrobe out of inexpensive materials.

Although LeMaire’s studio contract ended in March of 1959, he stayed on until the early 1960s, freelancing three features annually. A key campaigner to have the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences recognize costume designers, his department won the first time they were nominated for All About Eve (1950). Another win for Love Is a Many-Splendored Thing (1955) created his greatest worldwide fashion stir: the Chinese-style sheath dress. His last work here was for David O. Selznick’s Tender Is the Night (1961).

Jayne Mansfield gets fitted for The Girl Can’t Help It (1956).

Each movie star would have a mannequin with her measurements: at the far right is Gene Tierney’s, followed by Vera Ellen’s, and the sixth one down belonged to Lynn Bari, 1946.

What an extraordinary curtain call this department had in those wild 1960s as the studio system drew to a close. Credit Edith Head for What a Way to Go! (1964) and Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (1969), Ray Aghayan for the Flint films (1966-67), Caprice (1967), and Doctor Dolittle (1967), and Irene Sharaff for Cleopatra (1963) and Hello, Dolly! (1969). Not surprisingly Cleopatra set a new record, with 26,000 costumes utilized. Vittorio Nino Novarese designed for the men, and Renie Conley designed for the other actresses and extras.

The work-room on the south side of the building, circa 1936.

Each rack contains costumes pulled for separate productions.

The workroom circa 1965.

“I used to disappear into the wardrobe department,” recalled Darryl Zanuck’s daughter, Darrylin. “When I got home, I’d draw clothes designs and show them to my father. He’d write on them ‘great’ or ‘it stinks.’ ”

Darrylin later operated a dress shop in the Acapulco Hilton, where she designed the clothes sold and the fabrics they were made of, and ran a wholesale business.

Gwen Wakeling racked up an impressive resume working on over 85 films for Fox in the 1930s and 1940s including The Grapes of Wrath (1940) and How Green Was My Valley (1941). She was also responsible for dressing Shirley Temple for many of her films. Here she is seen going over some sketches in the Women’s Wardrobe building.

The wardrobe department closed in October of 1977, and its glittering collection merged with Western Costume. The department reopened in the late 1980s and now resides on the fifth floor of Bldg. 99. This building currently houses Twentieth Century Fox’s feature-film production offices. Head of production Emma Watts and her creative team are located in Bldg. 88. Meanwhile, a vestige of the building’s glamorous past remains: Running along the east exterior wall you can still see the opening where wardrobe could be distributed.

Costume designer Bonnie Cashin displays the sketches she created for Unfaithfully Yours (1948) in one of the fitting rooms turned workroom on the north side of the building. The quote above the mirror reads “He who spits against the wind, Spits in his own face . . .”

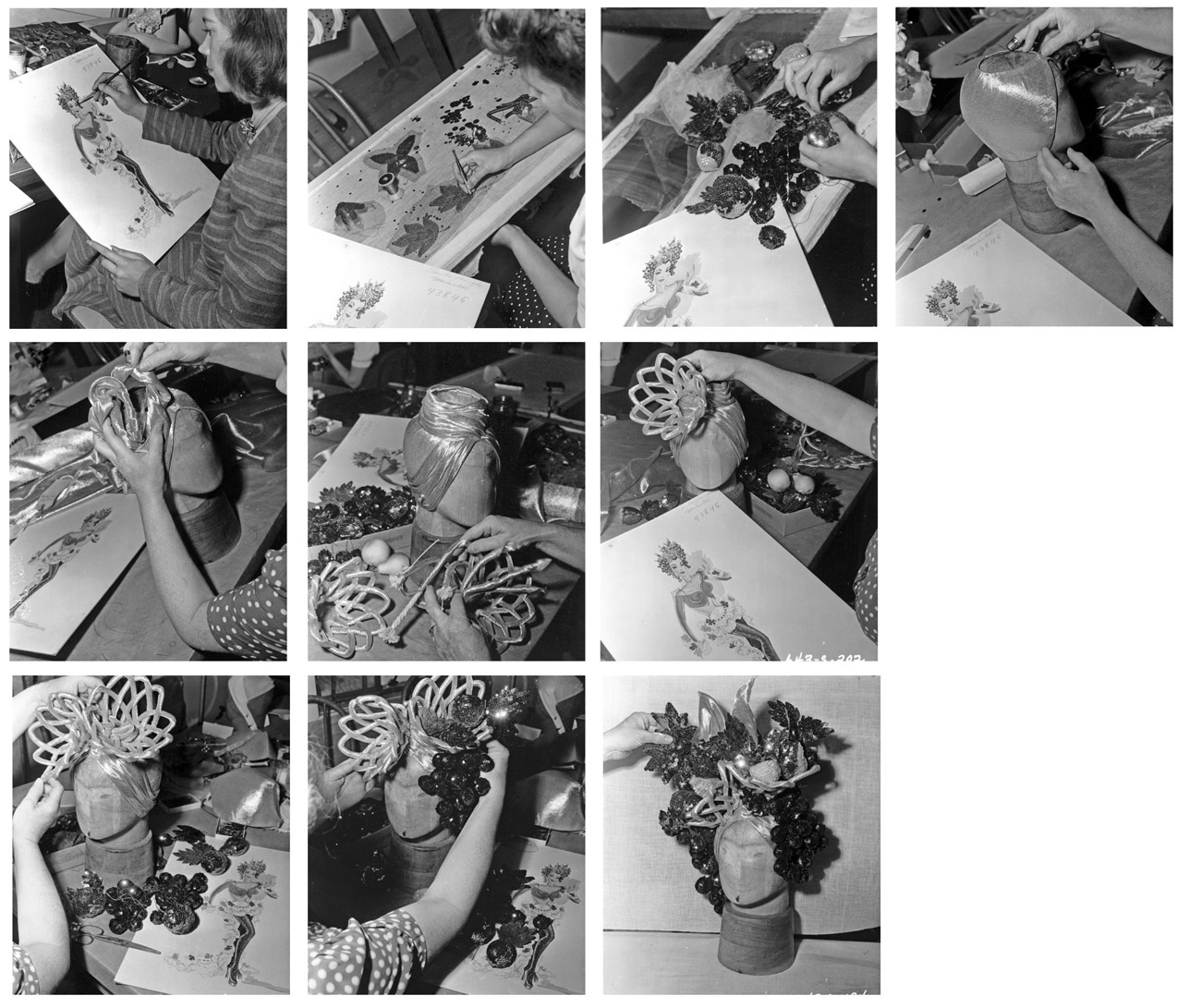

The Women’s Wardrobe department shows you how to make a Carmen Miranda hat!

And the resulting hat worn by Carmen Miranda on the set of Something for the Boys (1944).

Beau Bridges, Michelle Pfeiffer, and Jeff Bridges in The Fabulous Baker Boys (1989).

The entrance to Stage Twenty-two.

STAGE TWENTY-TWO (1966)

The prolific Bridges family has all appeared in Fox films and television shows. Beau Bridges, who starred in Norma Rae (1979) and Max Payne (2008), began making The Goodwin Games here in 2013. Beau’s father’s Lloyd appeared in A Walk in the Sun (1946), The Loner (1965–66), and the Hot Shots! films (1991-1993). Beau and younger brother Jeff appeared together in The Fabulous Baker Boys (1989). Jeff also composed some of the music for Fox’s John and Mary (1969), starring Dustin Hoffman and Mia Farrow.

STAGE TWENTY-ONE (1966)

Peyton Place for the 1990s? Certainly David E. Kelley’s Rome, Wisconsin, re-created on stages such as this one for the surreal Picket Fences (1992–96), was, in the creator’s words, “about community, family, the workplace, and the town integrated into this community.” Tom Skerritt (Alien), Kathy Baker (Edward Scissorhands), and South Pacific’s (1958) own Ray Walston were among its inhabitants.

Painted on its south wall, the stage has a mural depicting the light-saber battle between Darth Vader and Luke Skywalker from Star Wars V: The Empire Strikes Back (1980), completed in the spring of 1996. The film’s director Irvin Kirshner once said of film-making: “You guess at everything. You guess the script will be good, and that the actors you chose will be right. You guess that you’ll have enough money to finish the picture, and after every scene you guess that this will be the scene that will work. It’s a helluva way to spend millions of dollars!”

The mural of the climactic lightsaber duel between Luke Sky-walker and Darth Vader for Star Wars Episode V: The Empire Strikes Back (1980) adorns the south exterior wall of Stage Twenty One. All six Star Wars films distributed by Fox were not made here, but various places overseas, including the Fox Studios Sydney.

STAGE TWENTY (1966)

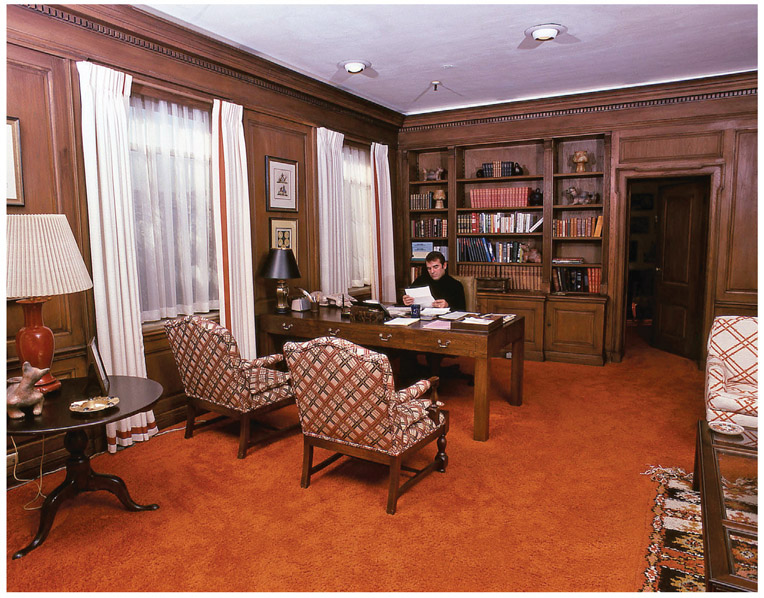

Who would have thought that when Rex Harrison was let go in disgrace in the 1940s, he would return in such triumph in the 1960s. It was impossible to ignore talent like his, as evidenced here on the set of Doctor Dolittle’s (1967) elegant study, where he performed “Reluctant Vegetarian” and “Talk to the Animals.” Although the film’s fans continue to consider it, in the words of one of its most memorable performers, Anthony Newley, “altogether marvelous,” Harrison found the film more difficult than Cleopatra (1963). The bad weather in England, and, later, in the Caribbean, proved to be a secondary problem to working with so many animals that—in the case of a chimp, Pomeranian puppy, and duck—bit him. There was also the goat that ate Fleischer’s script, and the parrot who yelled “Cut!” at inopportune moments.

A star on the rise when Joel Schumacher made Dying Young (1991) here, Julia Roberts got her start at Fox in Aaron Spelling’s Satisfaction (1988). That same year she appeared in studio’s sleeper hit, Sleeping with the Enemy (1991), and remains a major star at the company’s century mark. Most recently she returned to work in Tarsem Singh Dhandwar’s Mirror Mirror (2012, Relativity Media).

This is the set on Stage Twenty for Dr. Dolittle (1967) with Rex Harrison amongst the animals. That is the back of Anthony Newley’s head.

Julia Roberts had one of her best early roles in Dying Young (1991). Some of the interior shots were made on this stage. This photo from the opening scene was filmed on New York Street when it doubled for Oakland, California.

The east side of the Camera Building. Among the department’s breakthroughs was a camera that did not have to be immobilized inside a booth when sound motion pictures were introduced.

BLDG. 31: THE CAMERA BUILDING (1936)/BLDGS. 16-19 (1928)

As part of Darryl Zanuck’s expansion of the lot, Building 31 was built to house the camera department on the first floor, the script department on the second floor, and the studio switchboard on the third floor. Adjoining it were earlier facilities for the studio generator (publicized as big enough for a city of fifty thousand) and camera repair and maintenance. As of 2015, one of these original Westinghouse generators is still providing the power to Stage Nine. For years the studio offered a shoeshine and repair service at the east end of Bldg. 19 that made regular rounds.

“According to Dad, the most important man on the lot, the one you wanted on your side, was not Darryl Zanuck but Henry the Bootblack,” recalled Tom Mankiewicz. “He shined the shoes of every executive on a daily basis. They were constantly on the phone and talked freely in front of him while he worked. As a result, he knew everything that was going on at Fox: whose contract was being dropped, what project was going to get a green light or be canceled, and who was currently in or out of favor.”

Northeast entrance sign, circa late 1940s.

Loading dock for cameras on the west side of the building, 1940s.

Workers from the script department exit the southeast entrance.

It became “Joe’s [Quattrochi] Shoppe” for the same service in 1982. The shoeshine service and barbershop exist still today in the basement of Bldg. 88. Bldg. 31 is the one that had “Think 20th” painted on the south side during the Richard Zanuck era, and was the first building restored under the studio’s lot-wide preservation program, beginning in the spring of 1994. In 1998 the walk-way from this building to the commissary was refurbished and landscaped at a cost that caused employees to dub it “the million-dollar walkway.”

Avenue D as it appeared before the installation of “the Million Dollar Walkway” transforming it from a car thoroughfare to a pedestrian walkway, circa 1962.

Studio head Richard Zanuck stands in front of Bldg 31 hoping everyone will “Think 20th” the studio’s marketing campaign in the mid-1960s.

STAGE NINE (1928)

The oldest stage on the Fox lot, it once contained one of the most famous sets and key props in Fox history: Gene Tierney’s elegant apartment and portrait for Laura (1944). In June of 1943 Otto Preminger convinced the studio to purchase Vera Caspary’s popular novel, chose Rouben Mamoulian as director and his wife Azadia to paint the title character’s portrait for this set, and cast Jennifer Jones as star. Jones turned him down because mentor David O. Selznick did not like the project, and Mamoulian and Azadia were fired when he saw their initial efforts. Preminger ended up taking a photo of Tierney by Frank Powolny and having it enlarged and lightly brushed with paint to create the effect he wanted.

John Hodiak was considered for the role of the detective who falls for Laura, until Dana Andrews convinced Virginia Zanuck that he was right for the role on the aircraft carrier set on the backlot while he was filming Wing and a Prayer (1944). Although Laird Cregar was considered for the acid-tongued critic, Waldo Lydecker, who becomes fatally obsessed with Laura while transforming her into a sophisticate, Broadway musical-comedy star Clifton Webb was cast instead. Preminger wanted to use Duke Ellington’s “Sophisticated Lady” as the theme song, but Alfred Newman had other ideas, providing David Raksin to write the music.

“We were a mixture of second choices—me, Clifton, Dana, the song, the portrait,” recalled Gene Tierney. “Otto held us together, pushed and lifted what might have been a good movie into one that became something special.”

The east exterior wall has a mural depicting William Wellman directing The Ox-Bow Incident (1943).

Set still from Laura (1944) showing her elegant apartment as it appeared with the original portrait.

Tierney was back for The Razor’s Edge (1946) and a justly famous romantic scene with Tyrone Power on a sweeping staircase here, reputedly involving eighty-one technicians. Costar Anne Baxter attributed their sizzling onscreen chemistry to an off-screen romance, but Tierney was actually involved in a short-lived romance with a naval hero named John F. Kennedy, whom she had met when he toured the lot and her farmhouse set for Dragonwyck, on Stage Five.

It can safely be said that Celeste Holm earned her Academy Award for Gentleman’s Agreement (1948) on this stage. It contained the set of her character’s apartment for the key sequences toward the end of the film with Gregory Peck. She was certainly under pressure to do her best, because Darryl Zanuck—knowing her only as musical-comedy star Ado Annie, in Rodgers & Hammerstein’s Oklahoma!—doubted she was up to the part. So he tested her by having her perform these most important scenes first. It had been a rough first year for the star, who remembered having the unfortunate timing of coming to Fox after another Broadway star, Tallulah Bankhead, arrived, and caused plenty of trouble. Of course she passed the mogul’s test, and went on to enhance a number of Fox films, as much for her warm sense of humor as that impressive dramatic talent.

The world-famous Laura (1944) portrait that appeared in the film. Detective Mark McPherson (Dana Andrews), fatigued during his investigation, takes a rest in Laura’s apartment.

Here, Richard Todd as Scottish minister Peter Marshall delivered those stirring sermons in the recreated interiors of the Church of the Presidents in Washington, D.C. For the rest of his life Todd was proud to note that A Man Called Peter (1955), his Fox debut, surpassed the three most expensive Fox productions of the year: Untamed, The Tall Men, and The Racers at the box office. It is a reminder for us of Fox’s unique legacy for releasing many of the most inspiring pictures about faith and hope from The Song of Bernadette (1943), and those extraordinary companion pieces The Keys of the Kingdom (1944) and The Inn of the Sixth Happiness (1958), to I’d Climb the Highest Mountain (1951), The Robe (1953), Francis of Assisi (1961), The Gospel Road (1973), and Son of God (2014).

The lab where an experiment goes awry in the sci-fi classic The Fly (1958). Helene DeLambre (Patricia Owens) is about to find out what really happened to her husband Andre (Al Hedison).

Anne Dettrey (Celeste Holm) consoles Philip Green (Gregory Peck) in Gentleman’s Agreement (1947).

Two sci-fi films shot here include The Fly, (1958) with its iconic lab set, and Jerry Lewis’s Way . . . Way Out (1966), set in faraway 1994, in which he plays a space weatherman married to Connie Stevens.

The stage here was transformed by Walter Scott and interior designer Ted Graber into a royal garden party for noted film buff, Queen Elizabeth II, on February 27, 1983, with five hundred celebrities, business leaders, and government officials in attendance.

A record was set in American television history the very next day, when 106 million people tuned in to watch the two-and-a-half-hour series finale to M*A*S*H, made here. It was ironic that the studio’s most popular attraction at the time was shot on one of its least-desirable stages, since no one at the time had expected it to be such a hit. Not only was it one of the oldest sets, but it was also not invested with the same quality materials as the others. Cast and crew remember the stage as hot in summer, cold in winter, and infested with fleas and mice. With the end of the series’ eleven-year run, the studio donated two boxcar loads of memorabilia to the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C.

The cast of the hit TV show M*A*S*H (1972-83).

All in the Family: the television show Bones, shot here, stars Emily Deschanel, daughter of cinema-tographer Caleb Deschanel (Hope Floats, 1998; Anna and the King, 1999; Abraham Lincoln: Vampire Hunter, 2012) and sister of Emily—Zooey Deschanel (FOX’s New Girl, 2011–, [500] Days of Summer, 2009).

A mural of the making of The Ox-Bow Incident (1943) is painted on the east side of the stage, as viewed from over the shoulder of director William Wellman.

The TV cast of M*A*S*H on the historic last day of filming.

The April 1983 issue of the company’s newsletter Focus on Fox covering the royal visit of Queen Elizabeth and Prince Philip. The party was hosted by Nancy Reagan.

Tom Mix.

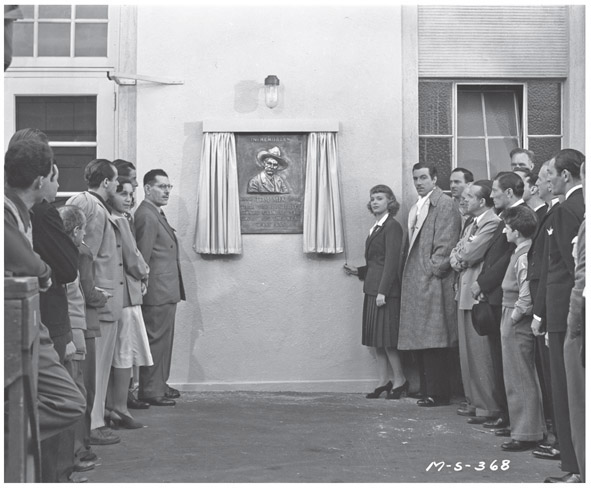

The dedication of the Tom Mix Barn with producer Sol Wurtzel on the left of the plaque and Pauline Moore and Cesar Romero on the right.

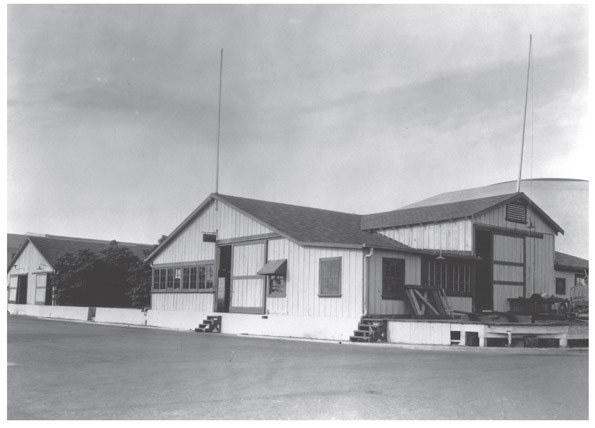

The exterior of the Barn circa 1929.

BLDG. 41: TOM MIX BARN (1920s)

Tom Mix housed Tony the Wonder Horse here, a sorrel he purchased in 1917 and rode throughout his career. His heyday was over when he departed the lot in 1928 to make films elsewhere, before retiring in 1934. When Mix was killed in an automobile crash in 1940, a plaque was dedicated to him here:

Tom Mix

1880–1940

Thru You Posterity Shall Glimpse the Glory of the West that Was.

Until Bldg. 89 was built, the property department was housed here, and then the mechanical effects and arsenal department, founded in 1923 by Louis J. Witte, moved in from the Western Avenue Studio’s west lot. A graduate from the University in Washington in engineering and a former employee of the DuPont Chemical Company, Witte was in charge of movie explosions, fires, fogs and smokes, sound effects, and the operation of practically every kind of gimmick imaginable for thirty years. The arsenal’s collection of weapons, ranging from pistols and rifles to crossbows and machine guns (valued at $135,000 in 1950) was considered one of the largest in the country.

Shortly after Pearl Harbor was bombed Witte received a call from Fort MacArthur, then Los Angeles’s main military base, requesting the loan of studio guns. By nightfall Witte and a studio crew had gathered fifteen Vickers, Thompson, Lewis, and Browning guns and four thousand rounds of ammunition. For a surprisingly long period of time this arsenal was the principal armament defending the city’s main airport.

The studio’s armory was located here for many years.

The building shows up as a train station in the first episode of Peyton Place and in Hush . . . Hush, Sweet Charlotte (1964), utilizing the corbels of the one that had been torn down, from Midwestern Street. Note that the studio street behind the building is named “Peyton Place Street.” By then office services was housed within. More recently, the Barn housed the production offices for David Friendly Productions, Shawn Levy’s 21 Laps Entertainment, and Fox Digital Studios.

Betty Grable poses with some of the armaments for Footlight Serenade (1942).

For many years the Sound Effects department was also located in the Barn.

The exterior of the Barn in 2007.

Bldg. 42 as it appeared in the 1930s as an Irish cottage with a thatched roof.

The original occupant of Bldg. 42, Irish tenor John McCormack, stands at right beside Charles Farrell.

Bldg. 42 as it appeared in 2007.

BLDG. 42: THE JANET GAYNOR BUNGALOW (1929)/BLDG. 44: THE WILL ROGERS BUNGALOW (1929)

California, it’s a great old state. We furnish the amusement to the world. Sometimes consciously. Sometimes unconsciously. Sometimes by our films. Sometimes by our politicians.

—Will Rogers

Among the monuments built and institutions named for that great American, Will Rogers, Bldg. 44, custom-built for the star, is entirely unique. It once faced the now-vanished formally landscaped Tennessee Park with its two World War I field guns at opposite corners. By the time he occupied it, the Oklahoma-born, part-Cherokee high school dropout had risen from Wild West trick roper and Ziegfeld Follies star to become the most popular draw in every form of media—newspaper, radio, and motion pictures—as a folksy humorist and a beloved humanitarian.

Appearing in films since 1918, Rogers signed his first contract with Fox on March 22, 1929, and then another in January 1935, making twenty films and becoming the highest-paid actor in Hollywood. Rogers’s daily routine included waking in time to ride his horse from his ranch in the Santa Monica hills to the beach to watch the sunrise, return for breakfast, and then arrive on the lot earlier than anyone else for his latest film. After riding home for lunch or dining at the Café de Paris, Rogers would use the bungalow to type his articles, which he then read to the delight of the cast and crew of his pictures.

Charles Farrell and Janet Gaynor, Hollywood’s most popular movie couple in the late 1920s and early 1930s.

Others recall that he used his car more often than the bungalow, parked near whatever stage or backlot set he was working on. Jane Withers, who worked with him in Doubting Thomas (1935), looked forward to his phone call during her tutoring session. “Is it time for recess?” he would ask. She would put on her roller skates and skate over to his bungalow, where she knew he kept the key over the door. There he taught her to play chess.

Upon his death John Ford, who directed three of his best films, hosted a memorial. During Rogers’s funeral at Forest Lawn, as fifty thousand mourners passed by the closed coffin, every studio in Hollywood stopped production. That evening the Hollywood Bowl was filled for another tribute. In movie theaters across the country two minutes of silence were observed.

“A smile has disappeared from the lips of America,” said John McCormack, “and her eyes are now suffused with tears. He was a man, take this for all in all, we shall not look upon his like again.”

McCormack’s neighboring bungalow (Bldg. 42) resembled the thatched-roof Irish cottages of his Fox film debut, Song O’ My Heart (1930), complete with shamrocks in the garden. When McCormack departed the lot, it was given to Janet Gaynor. She added a piano—when “talkies” came along and she began making musicals—and rose bushes along the fence. Winfield Sheehan made sure fresh flowers were delivered to her every day.

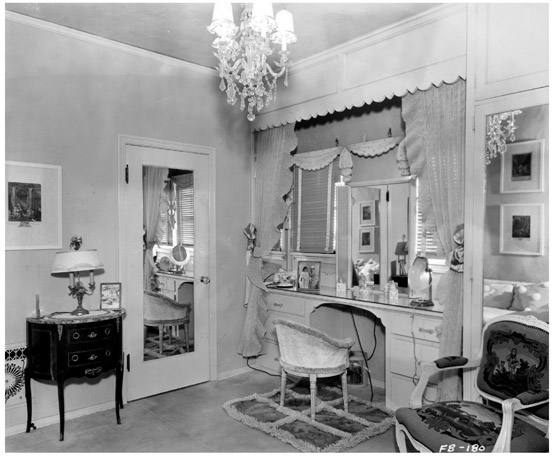

The sitting room of Bldg. 42 looking east, as decorated for Janet Gaynor.

“Janet Gaynor was a gracious and lovely lady,” recalled costar Ginger Rogers, “and Charlie Farrell was the handsome boyfriend every young girl coveted. I was surprised they weren’t in love with each other. I got the feeling they might have had a thing for each other at one time, though now they were just friends.”

“Janet and I were always receiving wedding anniversary presents in the mail care of the studio,” said Farrell. “The fans didn’t know what date our anniversary fell on, which is logical since we were never married.”

This cozy fire-place nook was original to Bldg. 42, and is still extant.

When Gaynor departed in the fall of 1936, the studio loaned the bungalow out to visiting stars. Warner Baxter was known to use the Rogers bungalow and cook his famous chili con carne, to the delight of coworkers. Myrna Loy remembered staying in the Gaynor bungalow while she made The Rains Came (1939). Steve McQueen got to use it while making The Sand Pebbles (1966).

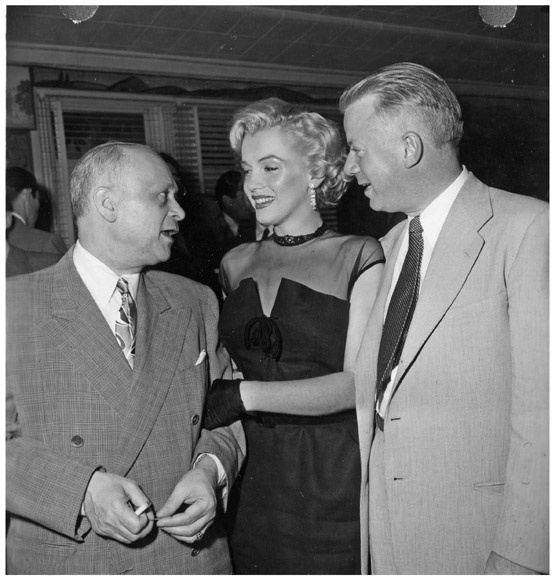

Joseph Mankiewicz occupied Will Rogers’s bungalow during his studio tenure. In 1960 the bungalows were joined for the offices of Jerry Wald Productions. After his misadventures with The Girl in Pink Tights (1955)—a project Marilyn Monroe refused to make—and Carousel (1956)—that he refused to make—Frank Sinatra finally made a movie on the lot and settled the lawsuit against him for Carousel by starring in Can-Can (1960). He used this bungalow while appearing in Von Ryan’s Express (1965), Tony Rome (1967), The Detective (1968), and Lady in Cement (1968).

Janet Gaynor’s dressing room.

Roderick Thorp, author of The Detective, wrote a sequel titled Nothing Lasts Forever in 1979, partially inspired by seeing The Towering Inferno (1974). Producer Lawrence Gordon saw no more than the cover of the book, with its fiery building and a helicopter, and impulsively purchased it and adapted it into Die Hard (1988). Interestingly, its star Bruce Willis had once passed Sinatra as an extra in The First Deadly Sin (Filmways, 1980).

Janet Gaynor poses by the north window in the front room of her bungalow.

Front room in the Janet Gaynor bungalow.

The bungalow later served Aaron Spelling and Leonard Goldberg during their reign as the best television producers in Hollywood, utilizing eight of the studio’s soundstages for their shows.

Although there are decorative bushes sculpted in various shapes throughout the lot, the one here of Bart Simpson—not to mention the Homer Simpson statue of his hand holding a doughnut—identifies the current residents. On the Rogers side is James L. Brooks. In the Gaynor side are The Simpsons writers. A worthy successor to the pioneering Paul Terry, Matt Groening’s self-proclaimed “celebration of the American family at its wildest” is the longest-running prime-time comedy series (animated or otherwise) in US television history. The show and movie have fun with its Fox connections, containing such town shops as The French Confection and Valley of the Dolls toy store, and guest appearances by Fox veterans Pat Boone, Donald Sutherland, Elizabeth Taylor, Susan Sarandon, Mark Hamill, Ben Stiller, Arnold Schwarzenegger, Anne Hathaway, and Rupert Murdoch. Groening’s Futurama (presented by “30th Century Fox”) likewise contains numerous spoofs on the studio’s product over the years.

View looking east of the bungalow as it appeared in 2015. It’s not hard to tell which production company now inhabits the space with a topiary of Bart at left and the standee of Homer’s hand reaching for a donut. The Tom Mix Barn can be seen behind Bart.

Will Rogers on the lot writing his famous newspaper column in his car.

Photo presumably submitted (and rejected—as the torn corner indicates) to Will Rogers with the publicist’s comments at the bottom.

Will Rogers’ bungalow dressing room at the time he occupied it. The exterior was specially designed in a desert style with a garden of rare cacti, century plants, mesquite and grease-wood. The stone on the exterior is the same that was used on his home in what is now the Will Rogers State Park.

Interior of Will Rogers’ bungalow looking north.

Interior of Will Rogers’ bungalow looking south. The large fireplace was still extant in 2015.

The second room in Will Rogers’ bungalow.

The spacious three room bungalow most likely built for Buddy DeSylva.

BLDG. 49: BUNGALOW 7 (1929)

This three-room bungalow was probably built for Buddy G. DeSylva, the prolific Broadway composer who joined up with Lew Brown and Ray Henderson in 1925 to form a songwriting and music publishing team, and then broke away in 1929 to produce films under contract to Fox for eight years. Years later Henry Ephron produced a Fox musical based on DeSylva’s life called The Best Things in Life Are Free (1956).

In later years writer/producer Chris Carter had his office here. He developed two projects for Twentieth Century Fox Television, The X-Files (1993– 2002) and Millenium. The X-Files, which inspired two feature films and a brief reboot in 2016.

Building 69 in the 1930s.

BLDG. 69: THE SHIRLEY TEMPLE BUNGALOW (1930)

There is no country in the world, both civilized and uncivilized, where at some time or another her pictures have not been shown. In the Orient she is called ‘Scharey,’ in Central Europe it is ‘Schirley,’ but throughout the English-speaking world, ‘Shirley Temple’ stands as a universal symbol of childhood. No child in history has been so well known or universally beloved.

—Hollywood trade paper Cavalcade, 1939

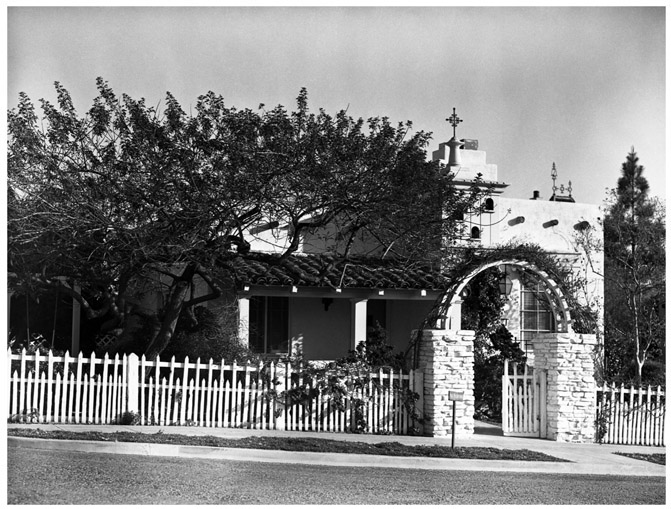

This cottage was built—painted blue and white—with a white picket fence for the arrival of European songbird Lilian Harvey in 1933. Her film My Lips Betray (1933) is notable for an early feature-film appearance by Walt Disney’s Mickey Mouse. The following year Disney provided Janet Gaynor’s nightmare sequence for Frank Lloyd’s Servants’ Entrance (1934).

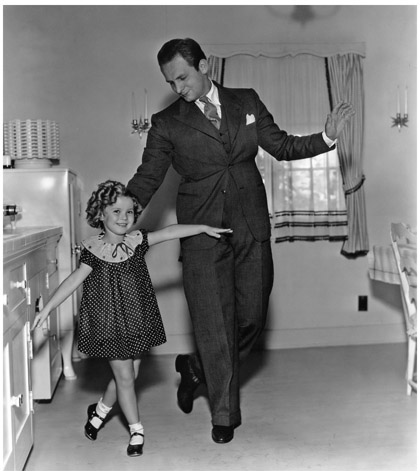

Shirley enjoyed this gift from frequent co-star Bill Robinson.

When Harvey walked off the set of George White Scandals (1934), costar Rudy Vallee launched a new star by replacing her with protégée Alice Faye. Glamorous Gloria Swanson inherited Lilian’s bungalow, “La Maison des Rêves” (House of Dreams), when she made Music in the Air (1934).

That December Gertrude Temple drove to the studio for an audition for her five-year-old daughter, who remembered that they were refused entry. Gertrude explained that Fox songwriter Jay Gorney (composer of the Depression-era classic, “Brother, Can You Spare a Dime?”) had seen one of little Shirley’s Frolics of Youth films, and had invited them to the studio to meet producer Lew Brown about a role in Stand Up and Cheer!.

Actress Lilian Harvey stands in front of the bungalow. Part of the Berkeley Square set can be seen in the distance.

Glamour portrait of Gloria Swanson taken during the filming of Music in the Air (1934) when she inhabited the bungalow.

Shirley Temple on the swing in the front yard of the bungalow. The Tom Mix Barn, Bldg. 54 Dressing Rooms A, and the back of Stages Three and Four can be seen behind her.

They were eventually granted access to the lot, and Shirley Temple’s subsequent success earned her this bungalow. From 1935 to 1938, she was the world’s most popular movie star, receiving an all-time record of 60,000 fan letters monthly. There were 384 Shirley Temple fan clubs nationwide, with 3,800,000 members. At her seventh birthday party twenty thousand fans in Bali met to pray for her. She rivaled President Franklin Roosevelt and Edward VIII as the world’s most photographed person at the time. The exceptionally popular doll fashioned in her image by the Ideal Novelty and Toy Company in 1934 (the most popular to date) saved them from bankruptcy. Meanwhile, Shirley worked six days a week on the lot for three hours a day, took her meals here, and then was tutored an additional three hours. She often made four films a year, requiring six or seven weeks each. Frances Klamt came to the studio as her private tutor in 1936. Fluent in several languages, Klamt served as the studio translator, and in 1939 became dean of education, teaching all of the lot’s children in the Old Writers’ Building for decades.

Original 1930s caption: “Shirley Temple, imitating her favorite comedian Harold Lloyd, reads to her pet Chihuahua in her bungalow.”

Shirley studying at her desk in the bedroom of her bungalow.

Shirley’s bedroom in the bungalow.

As a goodwill ambassador herself, Shirley received President Roosevelt (twice), the Chilean Navy’s chief of staff, the Australian prime minister, the son of Benito Mussolini, Prince Purachatra Jayakara of Siam, Amelia Earhart, Albert Einstein, H. G. Wells, and General John J. Pershing. In 1937 pilots of the first nonstop flight from Russia to the United States landed near the studio in order to meet Temple. Buddy DeSylva introduced her to Bill Robinson and his wife Fannie here before production on The Little Colonel (1935) commenced. One gift from “Uncle Billy” was a pint-sized, red-leather-seat racing car that she could gleefully buzz around the lot in, “once getting the knack of turning corners, pumping the clutch, and ignoring the brake!” Such antics and the unmuffled engine noise eventually relegated the car to her own driveway.

The living room of Shirley’s bungalow.

Shirley’s dressing table in the bedroom of her bungalow.

Despite the famous names that dwelled here after her departure, including John Barrymore, Ginger Rogers, George Cukor, Peggy Ann Garner, and Orson Welles, and its use as the studio dentists’ office and dispensary in 1955 (run by the physician brother of murdered mobster, Bugsy Siegel), until it moved into the craft services building, the bungalow remains unique because of Shirley Temple Black.

In 1934—a career high-water mark, with nine phenomenally popular features completed—Temple received a special miniature Academy Award statuette. Presenter Irwin S. Cobb said, “When Santa Claus brought you down Creation’s chimney, he brought the loveliest Christmas present that has ever been given to the world.”

Shirley got a small-scale piano in her bungalow.

The bungalow came equipped with a full kitchen. Here she is practicing with her dance coach Jack Donohue.

Shirley at her kitchen table in the bungalow with Nick Janios who is checking on whether she likes the food the Commissary is providing.

Child star Peggy Ann Garner inherits the bungalow in 1944.

Peggy Ann Garner enters the gate of the bungalow. The Janet Gaynor bungalow can be seen behind her.

Building 69 in 2015.

This building also served as the studio’s hospital until it moved to Building 99 in 1997. This is how it appeared in circa 1967.

Building 80 as it appeared in 2015.

BLDG. 80: OLD WRITERS’ BUILDING (1932)

When Sidney Kent and Will Rogers dedicated this building on December 9, 1932, with a cornerstone that still reads: “To the motion picture writers, the supreme storytellers of the 20th Century,” it represented the importance of screenwriting with the advent of sound motion pictures. The thirty writers that could be housed within rose to further prominence—in fact, to a level of respect achieved at no other Hollywood studio—upon the arrival of Darryl Zanuck. By 1941, fifty-three writers were under contract to him. He set a tough standard—scripts were expected to be completed within ten weeks, and weekly reports were issued to check on their progress—but he allowed them more responsibility, and preferred to develop producers from within their ranks.

“The Old Writers’ Building is something of a misnomer,” recalled Elia Kazan, “an old building where Fox housed young writers whose tenure was of uncertain duration.”

Dudley Nichols.

Indeed, the three-room writers’ bungalows with bathrooms that originally nearly encircled the building were preferred to the offices within its forty rooms. Look for the now-vanished ones to the east torn down in 1975 (where Bldg. 310 is) in The Lieutenant Wore Skirts (1956).

Wherever they were housed, many of Hollywood’s greatest have worked for Fox over the years, including Zanuck’s “Big Three”: Philip Dunne, a twenty-five-year veteran first hired in the spring of 1930 as a reader, who later wrote speeches for Adlai Stevenson and John F. Kennedy; Nunnally Johnson, known on the lot as “Robert Benchley with a Georgia accent,” who quipped that he wrote scripts for CinemaScope by putting the paper in the typewriter sideways; and Lamar Trotti, who came to Fox in 1934 when his boss Colonel Jason Joy became head of the story department, and excelled in producing Americana for the next twenty years.

Philip Dunne sits in a pensive mood in his office.

Nunnally Johnson appears to be having “writer’s block” in his office.

Other Fox writers included F. Scott Fitzgerald, whose difficulties during his Hollywood period are dramatized in Beloved Infidel (1959); Aldous Huxley, who adapted Jane Eyre (1944); Dudley Nichols, who weathered the Sheehan and Zanuck eras by sheer talent, a non-exclusive contract, and the support of John Ford (fifteen screenplays); Fritz Lang (Man Hunt, 1941); Jean Renoir (Swamp Water, 1941); and Elia Kazan (Pinky, 1949).

The lot’s feel-good writer, Valentine Davies, got the idea for his Academy Award–winning Miracle on 34th Street (1947) while he was in the army during World War II and went into Macy’s to buy a present for his wife. When Somerset Maugham refused to write a sequel to The Razor’s Edge (1946), the property lay dormant until the screen rights were signed over to Columbia for their 1984 remake as a trade for those of Romancing the Stone. Zanuck also consulted with—and produced the works of—John Steinbeck, and produced more films from eating, drinking, and storytelling companion Ernest Hemingway than any other studio.

Lamar Trotti.

The south side of the Old Writers’ Building. The large windows on the left of the first floor is where the studio’s school was housed.

Frances Klamt in her classroom with photos of her famous students on the wall, mid-1960s.

The schoolroom in 1945 with (L-R) unidentified girl, June Haver, Peggy Ann Garner, Barbara Lawrence, Roddy McDowall, and Barbara Whiting.

When Lamar Trotti died unexpectedly while writing There’s No Business Like Show Business (1954), Broadway imports Henry and Phoebe Ephron took over. Henry wrote and produced Carousel (1956) and Desk Set (1957), and hoped to make a movie about Elvis and manager Colonel Parker (with Orson Welles as Parker), but Spyros Skouras nixed it. Their Broadway-turned-film-hit Take Her, She’s Mine (1963) was based on letters their daughter Nora wrote from college.

W. Somerset Maugham holding his novel The Razor’s Edge that was turned into a Fox classic.

Nora Ephron—writer (Silkwood, 1983; This is My Life, 1992) and director (Sleepless in Seattle, Tristar Pictures, 1993)—never forgot attending the studio screening of An Affair to Remember in 1957. When her music editor Nick Meyers sought out and made a copy of the original recording of the score for Sleepless, she found Newman’s original far superior to a modern recording when they tried to replicate it.

The quill pen finial that was recently restored to the top of the building.

Truman Capote contributed to The Innocents (1961), the definitive screen adaptation of Henry James’s The Turn of the Screw. Husband-and-wife team Renee Taylor and Joseph Bologna uniquely developed an autobiographical screenplay (Made For Each Other, 1971) and starred in it. Loyal to Ring Lardner Jr. for his work at Fox (Laura, Forever Amber, The Forbidden Street), Darryl Zanuck boldly signed him to a new picture after the writer testified before the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC). He was ordered to fire him and complied. Zanuck was more successful in protecting directors like Lewis Milestone and Jules Dassin—who he sent overseas and was rewarded with the classic Night and the City (1950). Lardner was invited back to write the Oscar-winning script for M*A*S*H (1970).

“It was a real privilege to work at Fox in that [Zanuck] period,” said Francis Ford Coppola. “I remember going to the [commissary] and seeing Ryan O’Neal and Mia Farrow, who were working on Peyton Place. It was a big traumatic moment when, allegedly in a huff, she cut off all her hair—and there she was in the lunchroom with no hair. And on my way back to my office to work on Patton, I’d pass the set for the television series Voyage to the Bottom of the Sea, and I’d go sit all by myself in the submarine. All of a sudden I’d stand up and say, ‘Dive! Dive! Dive!’ Patton had any number of stylized touches that made the screenplay unpopular ten years before and very popular years later. I believe to this day that if I hadn’t won the Oscar for Patton I would have been fired off The Godfather.”

John Steinbeck prepares to introduce the collection of filmed short stories of O. Henry’s Full House. (1952). Director Henry Hathaway is at the left.

Lonne Elder III was the first African American to win an Oscar for the screenplay for Sounder (1972). Among Neil Simon’s works at Fox I Ought to Be in Pictures (1982) provides a memorable snapshot of Hollywood, and even a brief glimpse of the lot (with Ann-Margret as a hairdresser!) in the early 1980s.

Henry and Phoebe Ephron.

The original sign above the building’s entrance.

The stock film library, one of the studio’s oldest departments, is still in operation here. Established to supply stock footage for studio productions, its now-extensive library has been open to outside filmmakers since 1953. The script vault in the basement, the “steno pool” of twenty-five women, the fan mail department, and the studio schoolroom on the first floor on the southwest side of the building are gone. Frances Klamt’s schoolroom had two rows of wooden desks with the names of the famous children who studied there carved into them. She dedicated one wall to autographed photographs of all her famous pupils. Angela Cartwright recalled that minors only went to school here when they were not working on the set. In either case, twenty minutes of study were required before they could be pulled out of class for moviemaking.

“Imagine studying and then being called to the makeup department,” said Linda Darnell. “Next I will shoot a scene and then, with a few minutes to spare, rush back to class to split an infinitive. I would be kissing Tyrone Power and the school teacher would come and tell me it was time for my history lesson. I never before or since have been so embarrassed.”

“I always felt guilty when the crew sat around waiting and I hadn’t finished my three hours of schooling,” said Natalie Wood. “I always remember running to the set when I was called.”

“I finished high school here,” recalled Fabian. “I was there when all the contract players were let go in 1964 except for Stuart Whitman, Carol Lynley, and myself. The [studio] system crumbled, and the roles you needed to build a career just weren’t there.”

The building has since housed production offices for film (director Richard Fleischer) and television (writer/producer David E. Kelley). Kelley lived the Hollywood dream. More interested in screenwriting than in being a lawyer, he came to Fox at the invitation of Steven Bochco, who was looking for writers who knew about law for L.A. Law (1986–94). Rising through the ranks, he helped Bochco develop Doogie Howser, M.D. (1989–93), starring Neil Patrick Harris, before leaving the show to create Picket Fences (1992–96). He enjoyed success with Chicago Hope (1994–2000), The Practice (1997–2004), Ally McBeal (1997–2002), Boston Public (2000–04), Boston Legal (2004–08), and The Crazy Ones (2013). He even married a movie star, Michelle Pfeiffer.

Although the words over the front archway (“A play ought to be an image of human nature for the delight and instruction of mankind”) are long gone the original finial on the top of the building (a quill pen in an inkwell) was re-created by the studio’s metal shop and restored there recently.

BLDG. 79: JESSE L. LASKY BUILDING (1932)

After being ousted from Paramount during the Great Depression, Lasky, one of Hollywood’s true pioneers, set up offices here in 1932 as an independent producer. He made fifteen films for the studio over three years, with a fifty-fifty split of profits. He had his own projection room that was torn down when the large satellites were installed next door. Today the building is used for postproduction.

Filming the musical Redheads on Parade (1935) produced by Jesse L. Lasky.

The exterior of the Jesse L. Lasky Building in 2015.

Director Dorothy Arzner and screenwriter Sonya Levien (left), confer with Jesse L. Lasky about The Captive Bride that went unproduced. Levien wrote the screenplay for Cavalcade (1933) and State Fair (1933).

The massive canvas room.

Grip equipment.

South entrance of Grip Department.

BLDG. 310: GRIP DEPARTMENT/PRODUCTION OFFICES (2007):

One of the newest buildings on the lot, the first floor contains the current offices of the grip department and storage for all of the grip and lighting equipment, including a huge canvas-cutting room. The upper three floors house offices of various production companies, thereby removing many of the trailers that used to clog the lot. Look for the old grip and canvas department building—in its original location, in the northeast corner of the lot—in the Jeanne Crain/Jean Peters film Vicki (1953) as the repair shop.

Mel Brooks attributes his making of History of the World: Part I (1981) to a studio grip who asked him what his next picture was going to be. Brooks answered that it would be his biggest yet . . . called “History of the World!”

Northeast corner of Building 310.

Entrance to Stage Sixteen.

STAGE SIXTEEN (1937)

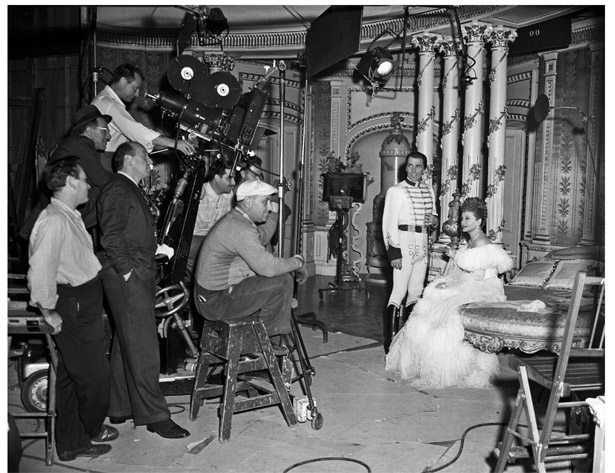

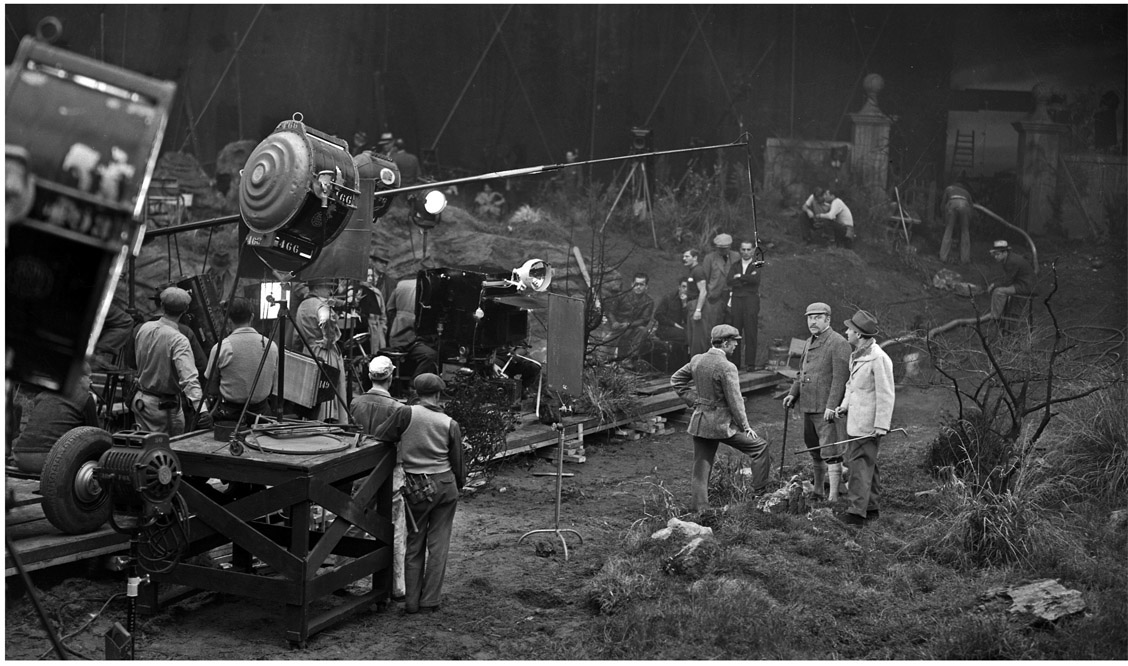

Darryl Zanuck permitted John Ford, a member of the Naval Reserve since 1934, to use his sound-stages to train filmmakers for World War II reconnaissance, training, and combat films for the Office of Strategic Services. Of course, escapist fare continued to flourish, including Ernst Lubitsch’s A Royal Scandal (1945). The elaborate private quarters of Russia’s Catherine the Great, played by Tallulah Bankhead, were built here.

“Grandfather [Frank Lloyd Wright] visited me on the set,” costar Anne Baxter recalled, “and watched Tallulah Bankhead working. He said quite loudly, ‘Not bad for an old dame,’ and Tallulah, who was uneasy about her age, visibly bristled. The next take required her to lightly tap me, but she responded with an uppercut that sent me reeling. Then she smiled sweetly and retired to her dressing room.”

William Eythe, standing next to Tallulah Bankhead, receives direction from Otto Preminger (hand in pocket by camera) during the filming of A Royal Scandal (1945).

Recovering from a heart attack, director Lubitsch asked Otto Preminger to finish the film. Preminger had special reason to be kind to Tallulah. She had enlisted the aid of her father (the Speaker of the House of Representatives) and uncle (a senator) to get his family, fleeing the Nazis, out of Europe.

The climactic courtroom scene in Peyton Place (1957), filmed here, reflects star Lana Turner’s own family tragedy when, less than five months after the film’s release, her fourteen-year-old daughter Cheryl stabbed Turner’s abusive lover Johnny Stompanato to death. That courtroom drama resulted in Cheryl’s acquittal and a 32 percent jump in ticket sales. Turner always had difficulty watching the film after that, since she is wearing jewelry Stompanato gave her.

Director Martin Ritt directs James Earl Jones in The Great White Hope (1970). Interiors for the film were shot on Stage Sixteen though it appears that this picture was taken during rehearsals on Stage Five or Six.

James Earl Jones knew all about prizefighting when he made The Great White Hope (1970) here because of his prizefighter-turned-actor father Despite the Tony he earned on Broadway and the acclaim for this film his most famous work for Fox was yet to come, as the voice of Darth Vader in the Star Wars films.

After making his debut at the studio in the Fox 2000 romantic comedy One Fine Day (1996), which used this stage, George Clooney was featured in a cameo in Terrence Malick’s The Thin Red Line (1998), and received praise for his performances in Fox Searchlight’s The Descendants (2011) and Fox 2000’s The Monuments Men (2014).

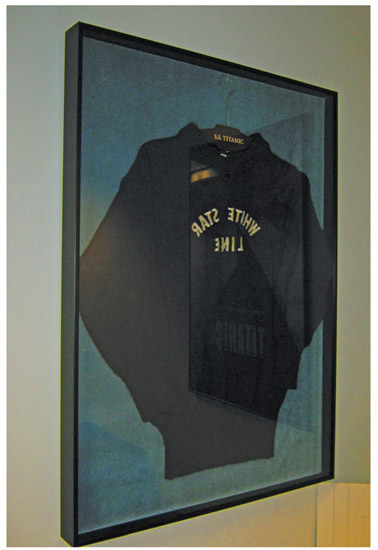

The studio added a permanent 500,000-gallon water tank for the flooded-kitchen set for the first sequences shot underwater here for Alien Resurrection (1997). It was the first Alien movie shot on the lot, at Sigourney Weaver’s request. The tank was later used for reshoots for Titanic (1997), a tragic story the studio perpetuated like no other. Besides its role in Cavalcade (1933), the 1953 Titanic, and in a 1966 episode of Irwin Allen’s Time Tunnel, there is The Poseidon Adventure (1972), inspired by the disaster, and references to it in The Rocky Horror Picture Show (1975) and Author! Author! (1982).

The set tank built for Alien Resurrection (1997) on Stage Sixteen. More horror: by 2015 FX’s American Horror Story (2011 -) was being produced on the lot, and the extraordinary Art Deco Hotel Cortez lobby and mezzanine set was built here for Season Five.

For many, Brad Pitt’s performance in Fight Club (1999) is his best. The interior scenes of Edward Norton / Brad Pitt’s home were shot here. Rising to stardom from television shows like Fox’s own 21 Jump Street, Brad Pitt married Jennifer Aniston, who sparkled in She’s the One (1996), Picture Perfect (1997), The Object of My Affection (1998), The Good Girl (2002), and Marley and Me (2008). Although he liked the script enough to send it to director Doug Liman, Pitt was initially not interested in starring in Regency’s stylish spy-vs.-spy action film, Mr. and Mrs. Smith (2005). He changed his mind and ultimately fell in love with costar Angelina Jolie here on the lot, and on this stage. He also appeared in Terrence Malick’s Tree of Life (2011), and made possible, as coproducer, Steve McQueen’s Oscar-winning 12 Years a Slave (2013).

Edward Norton and Brad Pitt in Fight Club (1998).

The spaceship Serenity in Joss Whedon’s cult hit Firefly (2002) was built on two stages, to accommodate its two levels. With a CGI-generated exterior, the cargo area and sleeping quarters were here. The cockpit, galley, and engine were on Stage Fifteen. Star Nathan Fillion never forgot his first day on this stage: “The big cargo bay door was open, and I walked up into the cargo bay up this ramp. Someone [called out] ‘Captain on deck!’ And everybody turned and stopped and did, like, a little mock salute. A couple of people applauded. And I thought, ‘Oh, my God. I just got on a spaceship.’ The moment was not lost on me. Every kid wants it.”

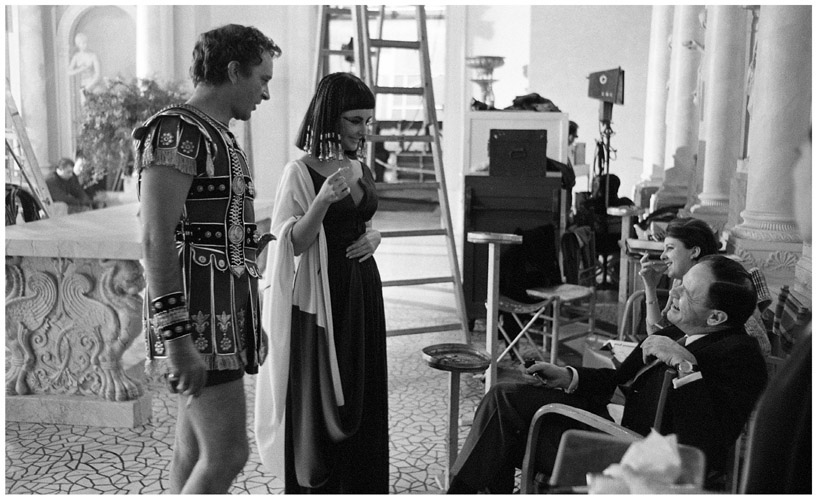

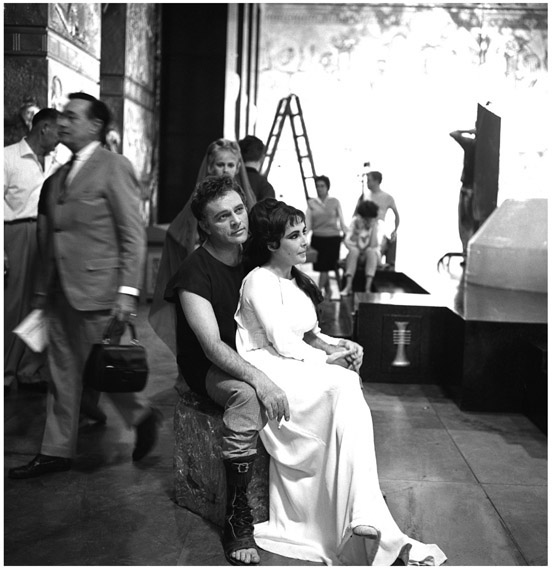

Twentieth Century Fox’s Jane Eyre (1944) featured an eleven-year-old World War II evacuee from England named Elizabeth Taylor. By 1958, when the studio wanted her again, she had rocketed to international fame. “She knocks Khrushchev off the front page!” observed Richard Burton. Spyros Skouras, Buddy Adler, and independent producer Walter Wanger were preparing a film they hoped would be a major cinematic event. They wanted a big important cast, and the best artisans for an epic to rival such recent blockbusters as Paramount’s The Ten Commandments (1956) and MGM’s Ben-Hur (1959). They wanted Alex North to compose a score that would be a masterpiece of the art form.

“We got what we wanted,” admitted David Brown. All this, and the most notorious production history the company has ever known, and the only film to close down the lot.

CLEOPATRA TIMELINE