You always have to keep changing in this business—attitudes, methods, everything.

—Alan Ladd Jr., president, Twentieth Century Fox

By 1971 Twentieth Century Fox typified the Hollywood film factory of that era, painfully transitioning away from the old studio system toward a future that was uncertain. Adolph Zukor’s Paramount—once William Fox’s chief rival—was the first to be swallowed up by a corporate conglomerate, Gulf + Western, in 1966. Transamerica bought United Artists in 1967. Jack Warner sold his studio away to Kinney National Services.

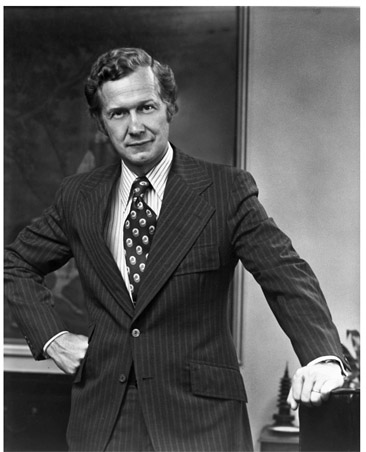

Dennis Stanfill

Like others, Fox, crippled by debt, sold off its history, including the company’s New York headquarters, the Western Avenue Studio, the Century Ranch, and studio props and costumes. Leading the company forward were Dennis Stanfill as chairman, and former Columbia executive Gordon Stulberg as president in charge of production. The titles were the same but the industry was different. Producers, directors, and stars—no longer under long-term exclusive contract—were the ones in power now, and Stulberg tried to court them into signing deals despite a spirit of retrenchment and cautious creativity.

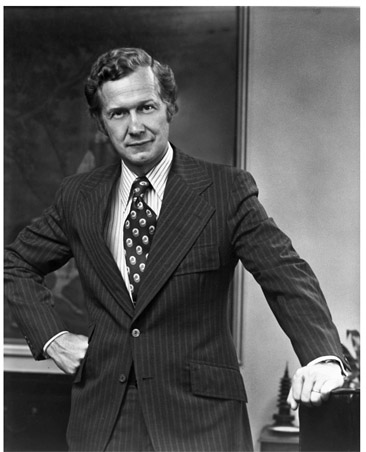

When Irwin Allen sought to dispel the fear by renewing filmmaking on a grand scale with The Poseidon Adventure, Stulberg would only pay half of it. Gathering friends, Allen got a loan and the film became the greatest moneymaking hit of 1973, earning him an industry reputation as the “Master of Disaster.” Although he discussed with Poseidon star Carol Lynley his idea to make an epic avalanche film as a follow-up, he ultimately coordinated a historic partnership with Warner Bros. to make The Towering Inferno (1974). The box office bonanza was the first time two major studios shared an expensive production, a trendsetting move that the studio would repeat in the years to come. Ironically Dennis Stanfill removed Gordon Stulberg in December of 1975 for low-key, low-performing films reflecting a budget-consciousness that he enforced. Most reflected a shattered world—like Hollywood—and celebrated the nonconformity and politics of the decade. Some of the best were from studio veterans: Paul Newman and Joanne Woodward’s The Effect of Gamma Rays on Man-In-The-Moon Marigolds (1972), Joseph Mankiewicz’s final film, Sleuth (1972), Philip D’Antoni’s The Seven Ups (1973), and Arthur P. Jacobs’s Planet of the Apes sequels. Martin Ritt produced a stunning trio of films about race relations: The Great White Hope (1970), Sounder (1972), and Conrack (1974). Among a new generation, Charles Grodin and Cybill Shepherd had memorable career boosts in Neil Simon’s The Heartbreak Kid (1972), as did James Caan in Cinderella Liberty (1973), and Timothy Bottoms in The Paper Chase (1973) and The Crazy World of Julius Vrooder (1974). The Last American Hero (1973), produced by Joe Wizan and starring Jeff Bridges, and Dirty Mary, Crazy Larry (1974) with Peter Fonda, explored the world of car racing. John Hough, who directed the latter, also made one of the decade’s best horror films, The Legend of Hell House (1973); Robert Mulligan’s The Other (1972) was another.

Gordon Stulberg

Inspired by the glam rock era the horror movie musical is a unique niche within the studio’s musical legacy. The company released its take on The Phantom of the Opera legend with Brian De Palma’s cult favorite Phantom of the Paradise (1974), and never was a Twentieth Century Fox trailer more true to its source than the one that declared: “You’ve seen all kinds of movies. But you’ve never seen anything like The Rocky Horror Picture Show…A different set of jaws!” Referring ironically to the enormous hit at Universal, produced by Richard Zanuck and David Brown, Rocky lost money even with its modest budget. It was not until it was discovered by midnight movie theatre audiences that the cult developed and net the film more than $50,000,000.

Now Dennis Stanfill looked to Alan Ladd Jr., who he promoted to vice president of production in 1975. Like Irwin Allen, Ladd did not believe Hollywood was through, and key to his success was his enthusiastic embracing of a new era of filmmaking and its filmmakers. He reawakened the company’s activity abroad by supporting Richard Lester’s all-star hit, The Three Musketeers (1974), Werner Herzog’s Nosferatu the Vampyre (1979), and Bernardo Bertolucci’s Luna (1979). He brought Mel Brooks to the lot to make Young Frankenstein (1974), launching a twenty-year collaboration with the studio. He allowed Brooks’s protégé Gene Wilder to direct comedies of his own, including Silver Streak (1976), initiating a popular screen partnership with Richard Pryor. This successful pattern—taking risks with people he trusted—earned him the presidency within a year, and the affectionate nickname of “Laddie” on the lot.

Sensing a hit franchise, he accepted a failing production from Warner Bros., entrusted it to neophyte director Richard Donner, cast studio veterans Gregory Peck and Lee Remick, and suggested that the satanic main character survive rather than be killed. The Omen (1976) was a smash hit, with the highest-grossing opening in the studio’s history: $4.3 million in three days. There were sequels (Omen II, Omen III), a television movie Omen IV: The Awakening, a failed television series, and a remake in 2006.

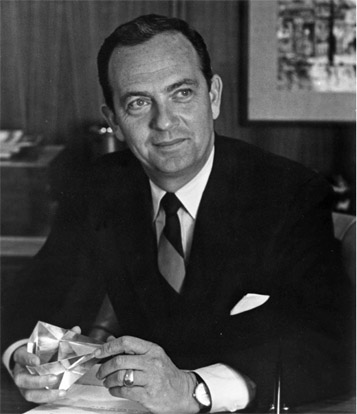

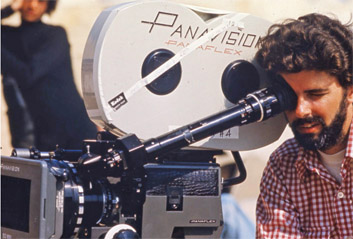

Then there was writer/director George Lucas who came to him to finance his homage to the Saturday-matinee serials of his youth when Universal—where he made American Graffiti (1973)—said no. With the studio still in a cash-strapped state, Laddie took the profits from The Omen and said yes.

Star Wars Episode IV: A New Hope was released on May 25, 1977. Not since The Robe had a single film thrust the studio—and the rest of the industry—into a new era of filmmaking, relying on special effects, improved sound, and the increasing value of merchandising and the foreign market. It even bumped the traditional summer release date from the middle of June to the end of May. The studio that had helped to pioneer wide-screen movies with stereo sound in the 1950s reintroduced it in Star Wars. Ray Dolby’s noise-reduction and stereo system received national attention when used on release prints of Star Wars, and became an industry standard.

Richard Donner

George Lucas’s THX (named after his film THX 1138, 1971) was likewise developed to create better theater sound, just as his Industrial Light and Magic (ILM) was founded in 1975 in a warehouse in Van Nuys to create better visual effects. With the success of Star Wars and its sequels, ILM was reopened in San Rafael and is, like THX, a division of Lucasfilm Ltd. Both would continue to be utilized by Twentieth Century Fox. The film also inspired another generation of Fox filmmakers.

George Lucas

“I saw Star Wars [on its] opening day at Grauman’s Chinese Theatre in Hollywood when I was fourteen,” recalled Dean Devlin. “I was ninth in line. It redefined the way I think about science fiction and fantasy. After that I knew what I wanted to do for the rest of my life!”

“I really got energized by Star Wars,” recalled James Cameron, “and in fact I quit my job as a truck driver and decided if I wanted to be a film-maker, I had better get going!”

“George Lucas’s Star Wars lifted us out of our depression in the 1970s and into an awareness and focus on space and its possible future,” noted broadcast journalist Walter Cronkite. “It stood by itself.”

Ridley Scott

By the end of 1977 the Ladd regime had reason to celebrate—not only the $150 million that George Lucas’s Star Wars reaped for Twentieth Century Fox (the final tally for Lucasfilm was $430 million worldwide by 1979), but also because of the acclaim generated for Fred Zinnemann’s Julia, and Herbert Ross’s The Turning Point. Together they garnered thirty-three Oscar nominations. Laddie had taken the studio’s feature-film division from $195 million to $301 million, and from three Oscar nominations to thirty-three. He had also saved the lot. That Alcoa lease on the studio property would have gotten prohibitively expensive had not Star Wars IV come along and allowed Dennis Stanfill to buy back the studio’s acreage and provide necessary upgrades and renovations.

The success of Star Wars IV also allowed Dennis Stanfill to further diversify the company. By now Fox owned three television stations under the subsidiary United Television Inc.: KMSP (Minneapolis), KMOL (San Antonio), and KTVX (Salt Lake City). To these he added resorts in California and Colorado, including the Pebble Beach Company and Aspen Skiing Company, as well as Coca-Cola Bottling Midwest. He formed a joint cable company with United Artists called Hollywood Home Theater, and embraced the home-video market by leasing an assortment of pre-1972 films to Magnetic Video Corp. and RCA. In 1979 he purchased Magnetic, which was reorganized into Twentieth Century Fox Video in 1982.

Laddie’s Midas touch continued. There were concerns that the story of a Southern textile mill union organizer was not box office, particularly when Jane Fonda, the star of the project, dropped out. Norma Rae (1979) provided a triumphant $11 million for the studio and a delightful new movie star named Sally Field. The tiny $2.3 million seminal coming-of-age story, Breaking Away (1979), made $10 million. Although the downward spiral of a late-1960s rock star seemed a depressing prospect, The Rose (1979) featured an impressive film debut for Bette Midler.

Laddie’s second important contribution to the studio’s science-fiction canon was approving Alien (1979) and its two key elements: Sigourney Weaver for the lead instead of the traditional male hero, and the unique vision of director Ridley Scott, who had likewise been inspired by Star Wars and stepped in after Richard Donner had turned it down. The new Fox franchise made Weaver a Fox star and brought James Cameron and David Fincher into the fold as directors of its sequels.

When Laddie began negotiations with Dennis Stanfill for a larger share of Fox’s profits, with his three-year contract ending in December 1979, the differences between the men came to a head. Stanfill wanted to continue to keep a tight rein on studio spending—too tight for Laddie, who departed in July.

In August Stanfill promoted vice president of European production Sandy Lieberson to president in charge of studio production, and Ashley Boone, whose seven years in sales and marketing included the promotion of Star Wars IV, to head distribution. That fall he made Alan Hirschfield, who had recently guided Columbia through its own troubled times in the 1970s, their boss as vice chairman of the board and chief operating officer.

Hirschfield brought with him his team in production (Daniel Melnick and protégée Sherry Lansing), marketing and distribution (Norman Levy), and television (Harris Katleman). Inevitably Sandy Lieberson and Ashley Boone departed. Hirschfield moved Norm Levy into distribution, and asked Daniel Melnick to head production. Wanting instead to make films independently at the studio, he suggested Sherry Lansing. She had recently developed The China Syndrome (1979), a Zanuck-like exploration of a controversial issue that broke Columbia’s opening-day box-office record, and the Oscar-rich Kramer vs. Kramer (1979) with Stanley R. Jaffe. The schoolteacher-turned-model-turned-actress-turned-studio-executive was now the first woman to head a major Hollywood studio. Variety issued the headline: “20th Century Gets a First Lady.”

Excitement rose in Century City with the release of the team’s first success, All That Jazz (1979). Bob Fosse’s outrageous autobiographical musical made money as one of the most honored films of the year. This enthusiasm carried into the new decade with the release of the last of Laddie’s productions, including Nine to Five (1980), and the distribution of Star Wars V: The Empire Strikes Back (1980).

Alan Hirschfield

While Sherry Lansing developed her own slate of films, Norman Levy sought “pickups” from independent filmmakers, forging successful distribution deals with Melvin Simon Productions (My Bodyguard, 1980; The Stunt Man, 1980), Albert S. Ruddy (Cannonball Run, 1981), and ABC Motion Pictures (Silkwood, 1983; Prizzi’s Honor, 1985). Profits and prestige were lost, however, when Norm Levy turned down Sherry Lansing’s request to distribute Chariots of Fire (1981). Growing antagonism led to fear of takeover when Herb Siegel’s Chris-Craft Industries, Inc., began to buy Fox stock in an effort to acquire those television stations.

Sherry Lansing strikes a pose on New York Street.

Allied with them was one of the most powerful oil and real estate billionaires in the country. Marvin Harold Davis from Denver, Colorado, wanted to make a “fun” investment in Twentieth Century Fox, with Aetna Insurance and Casualty Company and commodities broker Marc Rich as partners. He assured Stanfill and the board of directors that he was not a looter and would be hands-off with studio management.

Joe Wizan

Aware that they were vulnerable to a more-hostile takeover—and certainly, with no better offers in sight—the formal merger agreement was presented to stockholders on June 8, 1981. With the $722 million purchase the studio was folded into the Davis family’s TCF Holdings. Chris-Craft got what it wanted, too: a key position on the board of directors of Fox’s United Television stations.

Almost immediately Stanfill had reason to regret the sale, as Davis’s true intentions were revealed. To pay back his debt Davis sold off a large portion of that protective layer that Stan-fill had recently built up for the company. Then he showed interest in the studio’s valuable real estate. He wanted to sell it and redevelop it, with 2,200 condominiums and offices including the Fox Plaza Tower. In negotiations for a partnership with CBS—who would distribute Fox movies on cable TV and home video—he reasoned that production could resume at the forty-acre CBS Television City property.

This was not the act of an absentee landlord, and the hostilities led to Stanfill’s resignation on June 29, 1981. Although it reached the point where blueprints of the redevelopment were drawn up,, Marvin Davis decided that, due to the weak real estate market, the studio would remain in Century City for at least five years. In the meantime, he found that he enjoyed the status of Hollywood mogul, and promoted Alan Hirschfield to chairman and chief executive officer. He was not pleased with Sherry Lansing’s 1981–1982 offerings that posted a loss. For Christmas there were two hits: Modern Problems (1981) starring Chevy Chase, and Stanley R. Jaffe’s antiwar Taps (1981), featuring up-and-comers Tom Cruise and Sean Penn. The rest were ambitious but too often missed the mark. A lack of support—leaving her unable to make or protect movies she wanted to produce—was short-circuiting Lansing’s success.

Harris Katleman was more successful in revitalizing the television division by bringing Glen A. Larson to the studio to create The Fall Guy (1981–86), transforming Nine to Five into a popular series, and reintroducing Mr. Belvedere (Christopher Hewett instead of Clifton Webb) to audiences from 1985 to 1990.

Before he left, Laddie brought Richard Zanuck and David Brown back to the lot in 1979. At Universal they had re-teamed Paul Newman and Robert Redford in the Academy Award–winning hit, The Sting (1973), and they had launched Steven Spielberg’s career with Jaws (1975). Now they made The Verdict, directed by Sidney Lumet and starring Paul Newman, as the studio’s prestige Christmas release of 1982. That the producers—as well as Daniel Mel-nick and Sherry Lansing—left the lot by the end of that year exposed the management troubles within Davis’s regime. Melnick and Lansing and Stanley R. Jaffe made deals at Barry Diller’s Paramount, where Melnick had a hit with Footloose (1984), and Jaffe-Lansing Productions produced the monster hit, Fatal Attraction (1988).

As Hirschfield brought producer Joe Wizan back to Fox to replace Lansing in December of 1982, the last of her films were released, including Martin Scorcese’s King of Comedy (1983) and more Neil Simon with Herbert Ross’s Max Dugan Returns (1983). Norman Levy distributed Star Wars VI: Return of the Jedi (1983); Frank Yablans’s The Star Chamber (1983), beginning Michael Douglas’s career at the studio; the surprise hit, Mr. Mom (1983),with first-time producer Lauren Shuler; and Melvin Simon’s $100 million hit, Porky’s (1983). Fox Classics brought such films from abroad as Eating Raoul (1982), Betrayal (1983), the sleeper hit The Man from Snowy River (1982), and the Academy Award–winning To Begin Again (1982). The Gods Must Be Crazy, made in Botswana, became a distribution sensation in America in 1984.

Besides Joe Wizan’s success with Bachelor Party (1984) that brought Tom Hanks to Fox, and Revenge of the Nerds (1984), the studio finally had a major hit of its own with Romancing the Stone (1984). Sherry Lansing, who had green-lit the film in late 1982, had supported the career of its producer, Michael Douglas, since their days together at Columbia. Douglas in turn had faith in the script he had purchased in true Hollywood fashion from a Malibu waitress, and a director named Robert Zemeckis, who had only two minor movies to his credit.

Rupert Murdoch.

Barry Diller.

When Paul Newman turned down the leading role, Douglas stepped in front of the camera, too, with costar Kathleen Turner, chosen by Joe Wizan. The film earned $80 million, launching Zemeckis’s career, and the sequel, Jewel of the Nile (1985), earned $100 million.

But for hits like that, Marvin Davis suffered the embarrassment of Two of a Kind (1983) and Rhinestone (1984). He replaced Wizan in August of 1984 with Lawrence Gordon who produced the hit 48 Hours (1982) at Paramount. Hirschfield was out as well. Having made back his personal investment in Fox, and with partner Marc Rich mired in the largest tax-evasion case in US history, Davis was no longer finding it “fun” to run a Hollywood studio—especially after he had hired Barry Diller away from Paramount as the new chairman and chief executive officer in October of 1984. Almost immediately the relationship went bad, as Diller discovered the studio was sinking in $89 million worth of debt.

“The status of the company was not as promised,” said Diller. “I had to struggle financially just to keep it going. Aside from its financial status, the worst discovery was [that] there was very little of a real company with any kind of thoughtful rationale and any kind of integration working for it. Wisely or unwisely, Mr. Davis did not want to invest further in the company. That’s what brought Rupert Murdoch into the situation. I wanted him to come in very badly and worked to make it happen.”

Like William Fox, the Australian-born newspaper mogul Rupert Murdoch was an empire-builder. Ready to move into electronic media, he had already tried to purchase Warner Bros. Instead, he purchased 50 percent of TCF Holdings, for $250 million in March of 1985. Six months later, he paid an additional $325 million to complete his purchase from Marvin Davis. With his News Corporation (the third largest in the world), Murdoch had the capital to spend on Fox: $1.55 billion went to acquire the Metromedia group of six major-market independent television stations in 1985 that attracted other satellites, to realize his and Diller’s dream of a fourth American network. With founding members Jamie Kellner (president), David Johnson (advertising), Scott Sassa (publicity), and Garth Ancier (head of programming) they made television history on October 9, 1986 with the live debut of The Late Show Starring Joan Rivers (1986-87).

The Fox Broadcasting Company (stylized as FOX by consultant Chiat Day) successfully challenged the three major networks with the same kind of edgy, even controversial, entertainment and bold business practices that had built Murdoch’s newspaper business. There was Married…with Children (1987-97), The Tracey Ullman Show (1987-90) and from it The Simpsons (1989–), 21 Jump Street (1987-91), America’s Most Wanted (1988–), and COPS (1989–). Counterprogramming measures like adding weekend prime-time line-ups then swiping eight affiliates and the NFL from CBS prompted the Los Angeles Times to remark: “Like him or loathe him, Rupert Murdoch is the last of the great media swashbucklers, a throwback to the pirates, cutthroats and visionaries who used to run the business before it was engulfed and devoured by giant risk-averse corporate behemoths.”

“We had a very tentative start,” recalled Murdoch, “but without Barry Diller and his application and his genius—he’s a magnificent negotiator and a salesman—I don’t think we’d have FOX today.”

FOX or the Fox studio either. To save the studio, Diller instituted a 15 percent pay cut across-the-board, slashed department budgets, and laid off three hundred of its fifteen hundred employees.

“Barry was right. We were fat. We had too much overhead,” said Harris Katleman, who credited Diller with allowing him to bring Steven Bochco to Fox: “I would have spent six months justifying it, and I would have lost Bochco in the meantime.” Bochco became a long-term resident of the lot, in Irwin Allen’s old quarters, producing L.A. Law (1986–94), Hooperman (1987–89), and NYPD Blue (1993–2005).

Money—as well as a badly needed dose of nostalgic pride—was also provided with the release of Cocoon (1985). It was the brainchild of Lili Fini, whom Richard Zanuck married in 1977 after five years of marriage to Linda Harrison. The science-fiction fantasy was the couple’s first project as producers, with David Brown. But it took Barry Diller to get it green-lit, directed by Ron Howard, and starring a cluster of Fox legends, including Don Ameche, Hume Cronyn, and Jessica Tandy. Tyrone Power’s son even made an appearance. The media was inspired to sum up Ameche’s Academy Award– winning comeback this way: “Don Ameche: A Class Act—Again!”

James L. Brooks

For a year and a half Lawrence Gordon produced films like Jumpin’ Jack Flash (1986) with Whoopi Goldberg and Lucas (1986), bringing Charlie Sheen and Winona Ryder into the Fox fold before resigning due to illness. Embassy Communications chairman Alan Horn replaced him, but resigned after eight months, citing Diller’s micromanagement. The joke around the lot was that working for Diller was akin to extinguishing a fire on the Alaska oil pipeline. If you were too close, you burned to death; if you moved too far away, you froze.

John Davis

Diller promoted twenty-eight-year-old Scott Rudin—executive vice president under Gordon—to head production and hired his former ABC boss, Leonard Goldberg, as the new president and chief operating officer. Goldberg’s projects—Wall Street (1987), The Princess Bride (1987), Black Widow (1987), and James L. Brooks’s Broadcast News (1987)—had the confident sheen and social conscience that had been missing from the studio for years. Brooks, who had developed Room 222 (1969– 72) for the studio and then branched out to make movies at Paramount, was drawn back to the lot as much by his respect for Larry Gordon as for Barry Diller. Both soon had reason to be grateful for his return, with The Tracey Ullman Show (1987–90) and The Simpsons (1989–), and the founding of Gracie Films on the lot that would result in Big (1988), Say Anything (1989), War of the Roses (1989), and The Simpsons Movie (2007).

James Cameron

“I was there when Fox was a minute and a half from going under,” Brooks said. “But Barry Diller brought it off. It was sheer force of will.”

With Sylvester Stallone rampaging through Hollywood with box-office success in the 1980s as a former Green Beret named Rambo, Lawrence Gordon and Joel Silver saw to it that Arnold Schwarzenegger held his own at Fox with Commando (1985) and then Predator (1987). The latter brought director John McTiernan and producer John Davis (son of Marvin Davis) into the fold, initiated another franchise (including a merger with the Alien films), and is unique in Hollywood history for featuring two future California governors.

What a summer the assembled team had in 1988: Big in June, helmed by Scott Rudin and James L. Brooks, Die Hard in July, with the action-movie team of Lawrence Gordon, Joel Silver, and John McTiernan, and the distribution of Young Guns in August (with its inordinate amount of actors with famous fathers), produced by James G. Robertson and Joe Roth. Big forever catapulted Tom Hanks into the first rank of movie stardom as a comic and dramatic actor. Die Hard made Bruce Willis a movie star and initiated another franchise. The year did not end badly, either, with the winter release of Mike Nichols’s Working Girl (1988).

In 1989 Murdoch split Twentieth Century Fox Film Corporation into two separate entities known as Twentieth Century Fox and Twentieth Television, and hired Peter Chernin, the former head of production at Lorimar, to replace Garth Ancier. Chernin expanded FOX from two nights of programming a week to seven making it the number one network among the coveted eighteen-to-forty-nine-year-old audience and second in profitability to ABC beginning in the 1991–1992 TV season.

That summer James Cameron’s The Abyss (1989) was expected to continue the studio’s blockbuster winning streak. The filmmaker boldly announced: “If I can’t do what 2001: A Space Odyssey did for science-fiction films in space in the underwater arena, then I don’t want to make the movie.” Although the film set the ambitious pattern for Cameron’s later work at Fox—outdoing himself with special effects—and receiving critical acclaim (Peter Travers in Rolling Stone dubbed it “the greatest underwater adventure ever filmed”), editorial problems plagued the final result. The film was Fox’s biggest earner that year at $50 million, but it cost $60 million. The 40 percent box-office drop from the previous year cost Leonard Goldberg his job. Inspired by the success of Young Guns, Barry Diller hired Joe Roth to replace him, effective August 1, with the mandate to triple the studio’s output of feature films.

Joe Roth assembled a new team—Harvard-trained lawyer Strauss Zelnick as president and chief operating officer and Tom Jacobson as head of production - that created two instant classics for the 1990 holiday season. Home Alone (1990) was rescued from turnaround at Warner Bros. launching the career of Chris Columbus as the premier director of family films in Hollywood, and another Fox child star Macauley Culkin. It was Roth who recognized the promotional possibilities of Culkin’s iconic face shot (“the face that launched a thousand posters,” as Columbus referred to it). Roth also brought Tim Burton to the lot who cast Johnny Depp, who got his career start in FOX’s 21 Jump Street, Winona Ryder, and Fox veteran Vincent Price in Edward Scissorhands (1990).

With the turn of a new decade, Twentieth Century Fox’s home in Century City was once again in question. For necessary growth and access to the latest filmmaking technologies, Barry Diller had two options: build a new studio in Burbank, Santa Clarita, or Valencia, or undergo a $200 million redevelopment plan entailing an expansion of lot facilities from 1.1 million square feet to 1.9 million square feet. He chose the latter, which included plans for a new television broadcast facility, a new executive building, and studio postproduction upgrades.

Chase Carey

Diller then shocked the industry on February 24, 1992, when he announced his resignation. Having made television history and reinvigorating Fox’s film division, he wanted more of the company than Rupert Murdoch was willing to give. Just as suddenly Murdoch was no longer a distant figure on the Century City lot for a rearrangement of the Fox executive team. Fox’s film and TV operations were now the fastest-growing part of his forty-year-old, $8 billion global empire, yet the studio was still only turning out fifteen pictures a year, and Joe Roth’s box office clout, after more hits like Die Hard 2 (1990) and Sleeping with the Enemy (1991) and The Last of the Mohicans (1992), was slipping with the release of For the Boys (1991), Shining Through (1992), Hoffa (1992), and Toys (1992).

Chase Carey, a former Columbia executive who had been with Fox since 1988, became Murdoch’s right-hand man as chief operating officer of News Corp. Peter Chernin was put in charge of feature and television production as chairman, and Sandy Grushow was promoted into his old position. Under Grushow FOX became a full seven-nights-a-week network in 1993 enjoying success with In Living Color (1990–94), Beverly Hills 90210 (1990–2000), Picket Fences (1992–96), Melrose Place (1992-99) and Party of Five (1994-2000) and aggressively acquired sports programming. The Fox Children’s Network, launched in 1990, merged with Saban Entertainment to became Fox Kids Worldwide in 1995, based on the success of The Mighty Morphin Power Rangers (1993-96) and X-Men (1992-1997), and then the Fox Family Channel in 1997 with its acquisition of International Family Entertainment. It was sold to The Walt Disney Company in 2001.

Elizabeth Gabler

At the studio Chernin brought in Bill Mechanic as the new president of Twentieth Century Fox in September of 1994, hoping Mechanic’s skill at running home video and the international distribution of films at The Walt Disney Company could cushion them from bad theatrical film seasons as well. Meanwhile, vice president of production Elizabeth Gabler had an answer to the box-office doldrums. She had championed Anne Fine’s Madame Doubtfire until she and producer Roger Birnbaum found the right team in Chris Columbus and actor Robin Williams. It was a six-year process that produced that extraordinary hit Mrs. Doubtfire (1993).

Jim Gianopulos

Tom Rothman

Bill Mechanic hired James Gianopulos, formerly a senior executive at Carolco Pictures and Paramount Pictures, to expand overseas profits. He was so successful at it he was made president of the division—taking Twentieth Century Fox International from $298 million in annual revenue in 1993 to $1 billion by 2004.

Chernin’s studio restructure, unveiled in 1994, introduced new studio brands: Fox Searchlight Pictures, Fox Family, and Fox 2000, to ideally double production to thirty pictures a year. Tom Roth-man was brought on board in July of 1994 to head Searchlight Pictures. It was hoped that he could create the same kind of sophisticated, art-house films he had produced at Samuel Goldwyn. Ed Burns’s The Brothers McMullen (1995) was the first release, but it was first-time director Peter Cattaneo’s The Full Monty (1997), the highest-grossing film made in the UK, which launched it in a big way.

Chris Meledandri’s Fox Family Films was expected to cash in on the resurgence of interest in animated films in the 1990s, thanks to The Walt Disney Studio. Fox had periodically dabbled in animated feature releases, such as Richard Horner and Lester Osterman’s Raggedy Ann and Andy (1977); Ralph Bakshi’s Wizards (1977) and Fire and Ice (1983); Wayne Young and Peter Faiman’s FernGully: The Last Rainforest (1992); David Kirschner and Jerry Mills’s Once Upon a Forest (1993); and Maurice Hunt’s Pagemaster (1994). Now, Bill Mechanic invested $100 million to convert a 60,000-square-foot building in Phoenix, Arizona, into Fox Animation Studios Inc., and hired veteran animators Don Bluth and Gary Goldman to run it with a planned slate of one full-length feature film every eighteen months. The magical Anastasia (1997) was the first. Laura Ziskin, who had produced Pretty Woman (1990) for Touchstone Pictures, was chosen to head Fox 2000. Besides producing films ranging from Volcano (1997) to Inventing the Abbotts (1997), she also brought Richard Zanuck back to the lot with a three-year production deal. He re-imagined his own classic with Tim Burton’s Planet of the Apes (2000). It was Tom Rothman who introduced the two men, igniting a famed partnership that proved fruitful elsewhere, with Charlie and the Chocolate Factory (2005, Warner Bros.), Alice in Wonderland (2010, Walt Disney Pictures), and Dark Shadows (2012, Warner Bros.). Besides the new studio brands, The FX Channel (FOX “Extended”), The Fox Movie Channel, and Fox Sports also launched in 1994. Fox News began airing in 1996. Two years later Rupert Murdoch, to make FOX a full-fledged network, purchased the New World Communications television chain becoming the largest television station owner in the United States.

“Building Fox Sports from the ground up was something which will always live with me,” recalled David Hill, “but more particularly all the incredible men and women in front of, and behind the cameras who made Rupert’s dream become a reality. But, my proudest moment was running FOX in the late ‘90s. Working with Peter Roth, Mike Darnell, and a group of fearless television warriors, we took it to #2 behind NBC by 1999.”

Tom Jacobson ensured that the company’s traditional “monument” held its own with an impressive digital facelift, featuring a sweeping new panoramic view of the logo against the Hollywood sky specially timed for the release of James Cameron’s True Lies (1994). He had Jorge Saralegui as a new vice president of production—the first that had risen on the lot from script reader—responsible for Mark Gordon and writer Graham Yost’s action-thriller hit, Speed (1994). Contributing to its success was cinematographer-turned-director Jan de Bont—who had excelled in shooting action sequences for The Jewel of the Nile (1985), Die Hard (1988), and Shining Through (1992)—and new Fox star Sandra Bullock. She appeared in the sequel and a project closer to her heart, Hope Floats (1998).

Chris Meledandri

Peter Rice standing on Avenue of the Palms

When Jacobson announced plans to depart the studio to create his own independent production company in September of 1995, Peter Chernin replaced him with Tom Rothman. Rothman’s executive vice president Peter Rice and Saralegui approved more Gordon-Yost pictures (Broken Arrow, 1996; Hard Rain, 1998), and were responsible for bringing in talent like Baz Luhrmann (William Shakespeare’s Romeo + Juliet, 1996; Moulin Rouge, 2001), Danny Boyle (A Life Less Ordinary, 1997), and Bryan Singer (X-Men).

Dean Devlin and Roland Emmerich’s gloriously old-fashioned summer blockbuster Independence Day (1996) contributed mightily to the rising reputation and morale of Bill Mechanic’s Twentieth Century Fox. His team negotiated a record $1 billion film-financing package with Citicorp, and rebuilt the international, home video, music, and finance departments. It earned him the title of chairman and chief executive of Fox Filmed Entertainment. Chernin was promoted to president and chief operating officer of News Corp.

“After knocks, Fox rocks,” proclaimed John Brodie in Variety.

Sandy Grushow’s FOX then unleashed hits like David E. Kelley’s The Practice (1997–2004) and Ally McBeal (1997–2002). A third-generation writer for television, Joss Whedon transformed his 1992 feature film Buffy the Vampire Slayer into a television series phenomenon, produced by Twentieth Century Fox Television for the WB Network as a mid-season replacement in 1997. By 1999 Twentieth Century Fox Television was the leading supplier of primetime programming with a record thirty prime-time series. Of its kids and sports programming, “they are ten steps ahead of everyone,” observed Merrill Lynch media analyst Jessica Reif-Cohen. Inspired by the success of The Simpsons, FOX’s “Animation Domination,” included Mike Judge’s King of the Hill (1997–2009), Seth MacFarlane’s Family Guy (1999–2002, 2004–), and Loren Bouchard and Jim Dauterive’s Bob’s Burgers (2011–).

Forty-eight years after Darryl Zanuck had produced Kangaroo (1952), the first major American feature film made in Australia, Fox Studios Sydney opened there on May 2, 1998, as part of Rupert Murdoch’s plan to increase production on an international scale. The reasons were simple: Films were cheaper to make outside America, and now had to appeal to a worldwide audience. In the 1960s, the United States had accounted for approximately 65 percent of the world movie box office. Now that had dropped to 41 percent. Kim Williams was hired as chief executive of the studio, with Murdoch’s son Lachlan in charge of the company’s Australian operations.

James Cameron’s epic, Academy Award– winning Titanic (1997) certainly appealed to that international audience, contributing to the company’s top-grossing summer to date. The film required the construction of the Fox Studios Baja near the Mexican resort community of Rosarito Beach. It covered forty acres and featured the world’s largest water tank to date (holding 17 million gallons) for the 775-foot-long, 100-foot-tall, near-full-size, starboard-side re-creation of the Titanic. As costs escalated—and Cameron’s budget reports ballooned from $120 million to $200 million—the industry began to wonder if the studio had embarked on another Cleopatra (1963) debacle. Only by partnering with Paramount (who released the picture domestically in theaters and home video) did this Titanic arrive safely after 160 days of production at its premiere in Tokyo, on December 15, 1997. The film opened at number one, and remained there for a record-breaking fifteen weeks, finding success overseas in fifty-six countries.

Leonardo DiCaprio and Kate Winslet as Jack and Rose in the Best Picture winner Titanic (1997).

Other hits that summer included Chris Carter’s The X-Files: Fight the Future (1998), a big-screen adaptation of his TV phenomenon, family treats like Mirelle Soria and Tracey Trench’s Ever After (1998), starring Drew Barrymore, and John Davis’s Dr. Dolittle (1998), starring Eddie Murphy. Peter and Bobby Farrelly’s There’s Something About Mary (1998) surpassed the $100 million mark as the third-highest-grossing film of the year, and launched Cameron Diaz as a Fox star.

Aerial view of the Fox Baja Studios where the massive ship for Titanic (1997) was built.

Thanks to the negotiations of Peter Chernin and Domestic Film Group’s Tom Sherak, Fox was in the enviable position of releasing Hollywood’s most-talked-about summer film the following year. After sixteen years George Lucas was ready to release the first of three Star Wars prequels: Episode I: The Phantom Menace (1999). To promote the prequels Lucas had restored and revised his original trilogy, which Fox was happy to redistribute (they had by now made $1.8 billion on the three films. A further record-breaking 22 million copies were sold on home video. A further benefit to the studio were Natalie Portman and Ewan McGregor, stars of the prequels, who became Fox stars.

Shawn Levy

David Fincher

Meanwhile, Lindsay Law, who replaced Tom Rothman at Fox Searchlight, distributed Julie Taymor’s Titus (1999), Rothman’s team offered Mike Judge’s Office Space (1999), and Laura Ziskin finished off her career at the studio with Terrence Malick’s first film in twenty years, The Thin Red Line (1998), David Fincher’s Fight Club (1999), and a nod to the past, Anna and the King (1999). The question arose: Would Twentieth Century Fox change its name to reflect a new millennium? Years earlier Richard Zanuck had proposed that they do. The current administration said no..

“The Twentieth Century Fox logo stands for something,” explained Tom Sherak. “When that logo goes on the screen, people know it as something. It has a history to it, and that history is very important as to why we are a major studio.”

Darren Aronofsky

For that new millenium Peter Chernin oversaw the creation of a new production team: Tom Roth-man, as the newly created president of the Twentieth Century Fox Film Group, overseeing the films of the studio and Elizabeth Gabler’s Fox 2000, Hutch Parker, the new president of production, and Peter Rice running Fox Searchlight. Together they forged new partnerships with Regency Enterprises (including the Academy Award–winning 12 Years A Slave), Dune Entertainment/Color Force (The X-Files: I Want to Believe, Marley and Me, The Diary of a Wimpy Kid), DreamWorks (Cast Away, Minority Report, Road to Perdition), and TSG Entertainment (The Maze Runner franchise), while maintaining others with George Lucas (Star Wars II: Attack of the Clones, Star Wars III: Revenge of the Sith), Ridley Scott (Kingdom of Heaven, Prometheus, The Counselor, The Martian), James Cameron (Avatar), and Shawn Levy (Night at the Museum).

Inspired by the success of the Warner Bros./DC Comics’ Superman and Batman films, a collaboration with Marvel yielded two new franchises: X-Men (2000–14) and Fantastic Four (2005–15). Helping to make the X-Men films so successful was co-producer Richard Donner, twenty-four years after he launched the Omen series, and more importantly his wife Lauren Shuler Donner. All of these partnerships created a new array of Fox stars, including Colin Farrell, Ashley Judd, Hugh Jackman, Ben Stiller, and Michael Fassbender.

After a near-merger with MGM seventy years before, and decades of various partnership discussions, Fox signed an agreement in November of 2000 to take over foreign distribution of that studio’s films. The following year they added the international distribution of their home video releases.

Elizabeth Gabler’s Fox 2000 produced thoughtful thrillers like Joel Schumacher’s Phone Booth (2003), a smash hit biography of Johnny Cash, Walk the Line (2005), and the company’s two biggest hits of 2008 (Alvin and the Chipmunks and Marley and Me). Yet it remains unique for its celebration of books including The Devil Wears Prada (2006), Ramona and Beezus (2010), The Chronicles of Narnia: The Voyage of the Dawn Treader (2010), Water for Elephants (2011), The Book Thief (2013), The Monuments Men (2014), The Fault in Our Stars (2014), The Longest Ride (2015), Paper Towns (2015), Bridge of Spies (2015) as well as the Percy Jackson franchise. Gabler’s tenaciousness—it took seven years to make Robert Zemeckis’s Cast Away (2000), and ten for Ang Lee’s Life of Pi (2012)—paid off.

Nancy Utley

Under Peter Rice—with a team including Nancy Utley and Steve Gilula that would take over in 2009—the Fox Searchlight tradition of unfiltered, very personal slices of everyday life continued. There was Gurinder Chadha’s inspirational 2003 hit, Bend It Like Beckham, Zach Braff’s Garden State (2004), and Alexander Payne’s acclaimed Sideways (2004) and The Descendants (2011). Jared Hess’s Napoleon Dynamite (2005) was the studio’s biggest grosser of the year, at $45 million.

Steve Gilula

Jason Reitman entrusted first-time screen-writer Diablo Cody with Juno (2006), and the film earned her an Oscar and the film, a gross of $230 million worldwide. Michael Arndt’s Little Miss Sunshine (2007) produced another Oscar for screenplay and two new stars in Steve Carell and Abigail Breslin. Besides Adrienne Shelly’s Waitress (2007) and Marc Webb’s (500) Days of Summer (2009), director Darren Aronofsky inspired career-defining performances from Mickey Rourke as The Wrestler (2008) and Natalie Portman as The Black Swan (2010).

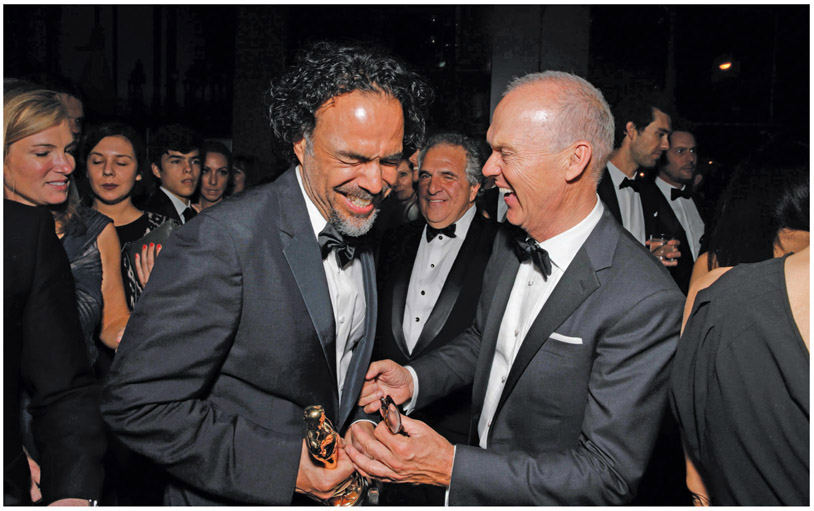

Terrence Malick was back to provide The Tree of Life (2013). Wes Anderson provided Fantastic Mr. Fox (2009) and The Grand Budapest Hotel (2014). John Madden provided The Best Exotic Marigold Hotel (2011) and a sequel in 2015. John Crowley’s Brooklyn (2015) and Davis Guggenheim’s He Named Me Malala (2015) upheld the Zanuck storytelling traditions. There were even two multi-Oscar Best Picture Academy Award winners: Danny Boyle’s Slumdog Millionaire (2008) and Alejandro Iñárritu’s Birdman (2014).

The cast and crew of Slumdog Millionaire (2009) celebrate on Oscar night.

When the disappointing box-office returns of Fox Animation Studios’ second feature, Titan A.E. (2000), forced the closure of the six-year-old animation studio in Phoenix, Arizona, Fox Animation president Chris Meledandri oversaw the transformation of Blue Sky Studios from special effects (Alien Resurrection, 1997; Fight Club, 1999; Titan A.E., 2000) to an animated-feature division that produced the Ice Age franchise, Robots (2005), Dr. Seuss’s Horton Hears a Who (2008), Rio (2011), Epic (2013), Rio 2 (2014), and The Peanuts Movie (2015).

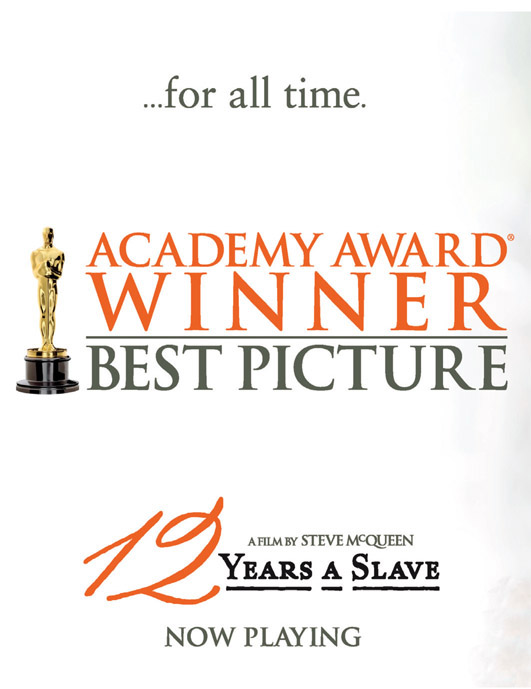

12 Years a Slave (2013) also won the Academy Award for Best Picture.

Hutch Parker

In 2000 Sandy Grushow, now heading FOX and Twentieth Century Fox Television, positioned Gail Berman to run FOX. The former head of Sandollar Productions, and founding president of Regency Television, took the network to the number one spot for the first time. Although FOX hit the target as the highest rated among eighteen to thirty-four-year-olds for the first time in 1998, Berman captured the even greater 18-49 demographic beginning in 2004 with one of the networks “reality” shows that were redefining the television game show. It was Rupert Murdoch’s daughter Elisabeth who had urged the creation of an American version of Simon Fuller’s popular British hit, Pop Idol (2001). It became American Idol (2002–16).

Gail Berman’s counterparts at Twentieth Century Fox Television, which continued as the leading supplier of primetime programming in the industry, were Dana Walden and Gary Newman. Their shows were: Judging Amy (1999–2005), Stark Raving Mad (1999–2000), 24 (2001–10), Firefly (2002), Arrested Development (2003–13), How I Met Your Mother (2005–14), Burn Notice (2007–13), Dollhouse (2009– 10) and Modern Family (2009–).

Hutch Parker topped a record-breaking 2003 (with hits like X2: X-Men United, Cheaper by the Dozen, Master and Commander: The Far Side of the World) with Roland Emmerich’s The Day After Tomorrow, and Dodgeball: A True Underdog Story in 2004. Helping him by bringing his Predator and Dr. Dolittle franchises into the twenty-first century was John Davis, who produced I, Robot (2004) and Garfield (2004). There was also a a new family classic, Because of Winn-Dixie (2005). By 2006 Fox brought in over $5.8 billion—nearly twice what it had earned at the beginning of the new century. That year was a particularly good one, with Night at the Museum, The Last King of Scotland, Borat, and Notes on a Scandal. In 2008 a new division was launched: Fox International Productions, to develop relationships with overseas filmmakers in key markets, including India and Russia.

On June 30, 2009, Peter Chernin resigned and created his own Fox-based company, Chernin Entertainment, to release films and TV shows, and The Chernin Group to continue his media strategies that had brought Fox into the digital age. Chase Carey, who had served as co-chief operating officer with Chernin from 1996 until 2002, returned to the lot as his successor. The media noted that among Murdoch’s subsequent promotions—Tom Rothman and Jim Gianopulos, as co-chairmen of Fox Filmed Entertainment, running television now as well, and Nancy Utley and Steve Gilula, as chief operating officers of Fox Searchlight—Peter Rice was emerging as his protégé as chairman and CEO of the Fox Networks Group. Murdoch also split his empire into two publicly traded businesses to separate the valuable Fox entities from the less-successful newspaper division, now plagued with scandal. The allegations of phone hacking and police bribery had shut down the British News of the World in 2011. Thereafter, News Corp. would incorporate all of the print, digital and information services in the United States while Twenty-First Century Fox incorporated all the filmed entertainment, television, cable and satellite assets.

Emma Watts

The final shakeup occurred at the end of the year when, amid a slate of films including John Madden’s The Best Exotic Marigold Hotel (2012), Ridley Scott’s Prometheus (2012), Sacha Gervasi’s Hitchcock (2012), and Benh Zeitlin’s Beasts of the Southern Wild (2012), Tom Rothman stepped down.

The director (Alejandro G. Inarritu) and star (Michael Keaton) of the Oscar-winning Birdman (or The Unexpected Virtue of Ignorance) (2014). Jim Gianopulos is seen between them.

The FX Channel came into its own under Peter Liguori, earning acclaim and notereity for pushing the creative envelope with its edgy programming even further than FOX. Its shows included It’s Always Sunny in Philadelphia (2005–), Damages (2007–12), Justified (2010–15), and American Horror Story (2011–).

Liguori took Gail Berman’s place at FOX in 2005 when she departed to run Paramount. In the tradition of Sherry Lansing, Berman was the first woman to run a television and motion picture studio. In 2014 FOX was combined with Twentieth Century Fox Television into the Fox Television Group headed by Dana Walden and Gary Newman because of their continued success with shows like How I Met Your Mother (2005–14), Glee (2009–15), Modern Family (2009–), White Collar (2009–14), New Girl (2011–), Homeland (2011–), Sleepy Hollow (2013–), and Empire (2015–). That same year Gail Berman was back launching The Jackal Group in partnership with the Fox Networks Group to produce television shows and feature films.

In November of 2014 Rupert Murdoch got Jim Gianopulos a new creative partner in DreamWorks former CEO, Stacey Snider. By then, determined as ever to grow his empire against the threat of new digital superpowers like Google, Comcast, and Time Warner Cable, he made news trying unsuccessfully to purchase Time Warner. Meanwhile, head of production Emma Watts engineered a resurgence of Twentieth Century Fox pictures—overshadowed by the success of Searchlight and Fox 2000—with the release of David Finscher’s Gone Girl (2014), and by repackaging the X-Men, Night at the Museum, and Planet of the Apes franchises. The Apes films were produced by Peter Chernin, who also gave her another Ridley Scott spectacle, Exodus: Gods and Kings (2014). It all helped make Twentieth Century Fox the numberone studio in Hollywood once again, with a record $5.5 billion in global ticket sales, breaking the record previously held by Paramount Pictures in 2011. That was a proud feat for a company going into its hundredth year. Interestingly, it began(Life’s Shop Window, 1914) and ended (Joy, 2015) its millennia producing stories about survivors.

In March of 2014 Rupert Murdoch promoted his sons. Lachlan took charge of both divisions of News Corp. as non-executive co-chairman with his father.

Younger son James was named co-chief operating officer with Chase Carey.

Stacey Snider.

The Fox Network Center.

After its birth at the Fox/Metromedia Square, the old KTTV studio at 5746 Sunset Boulevard in Hollywood, the FOX network moved—along with KTTV, KCOP and Fox Sports—to the Fox Television Center at 1999 South Bundy Drive in West Los Angeles in 1996. FOX and Fox Sports then moved into this building specially designed for them with two sound stages for live broadcasts. It was Rupert Murdoch’s second wife Anna who commissioned a California artist to create the hard-to-miss, thirty-six-foot-tall, ten-panel, tin and wood mural of his right index finger in the lobby.

For most of the twentieth century this was the site of the major parking lot “B”for the studio. Then it became the temporary site for a crafts building in the 1970s, before this building was built in 2006. Besides housing offices for Fox 21 and the studio gym, The Simpsons-themed Moe’s Café on the first floor—the smallest and most casual of the three studio eateries—is the only one to offer all three meals at the urging of Fox News and Fox Sports personnel, who work late into the night. The large patio hosts lot-wide events, including launches for new TV shows, health fairs, Food Truck Friday, and a barbecue once a week during the summer months.

Moe’s neon sign.

The large plaza in front of Bldg 103.

Dining room at Moe’s.

Moe greets you as you enter.

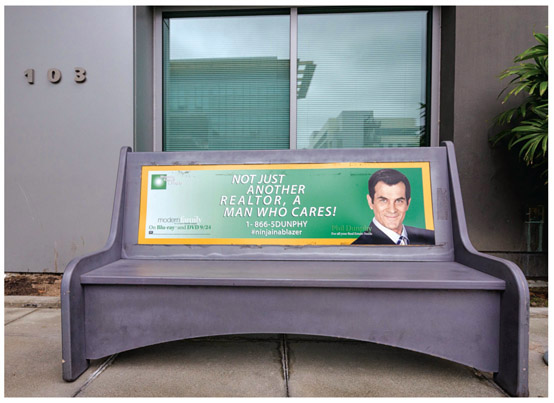

A bench commemorating Modern Family (2009–).

View of Bldg. 89 in the 1930s when it was the Prop Building. The north end of the building has been covered by the Hello, Dolly! (1969) set since 1968.

“They got so used to seeing me around Fox that they counted me in the annual inventory of props.”

- Tyrone Power, star of 40 Fox films

This building’s name is something of a misnomer, as founder William Fox had nothing to do with it. He made two known visits to the lot: once, in 1923, to purchase the property, and another in 1936 as part of a West Coast visit. He walked around that time and was recognized by no one.

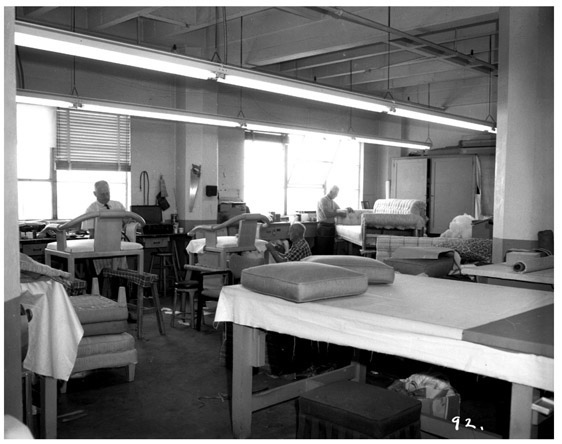

By 1981 the building just needed a name, and in July of that year it officially got one in an employee contest. Howard Van Amstel (corporate supervisor of purchasing) and Roy Mazza (accounting clerk for feature-film production) both turned in the name suggestion on the same day. The building’s three stories—100,000 square feet, plus basement—were in fact designed by Thomas K. Little to hold enormous amounts of weight for his property department, as well as the upholstering and furniture-making plant.

The old docks where props would be loaded onto trucks and the massive freight elevator were still extant in 2015.

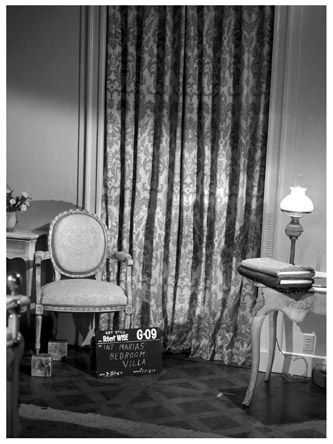

Darryl Zanuck chose his desk from this collection, an imposing one built to resemble George Washington’s. Among rugs worth $75,000 and Gobelin tapestries could be found bed headboards you can trace back decades, from the twin oval ones from Shirley Temple’s Stowaway (1936) that became Sharon Tate’s deathbed in Valley of the Dolls (1967) to Loretta Young’s fancy one in Café Metropole (1937) that became James Garner and Polly Bergen’s in the honeymoon suite for Move Over, Darling (1963).

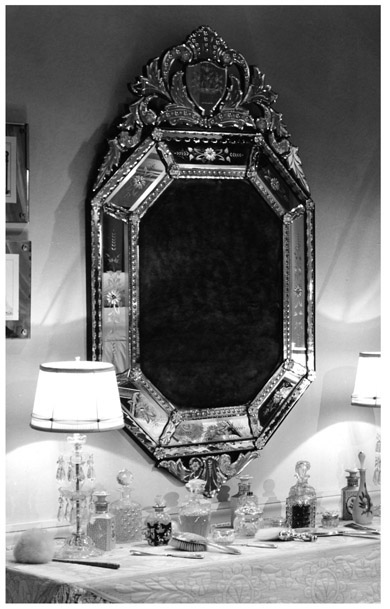

This lovely gilt mirror, as seen here in Laura (1944), hung around for years. It later decorated the office of the Charles Townsend detective agency in Charlie’s Angels (1976-81).

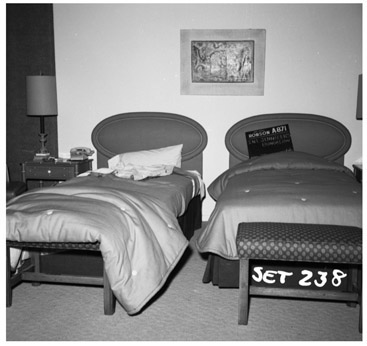

These twin headboards had a long life as well: they were used by Shirley Temple’s character in Stowaway (1936) and thirty years later were used in the death scene of Sharon Tate’s character in Valley of the Dolls (1967).

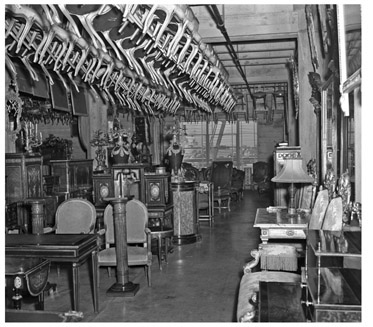

Interior of Bldg. 89 with its massive octagonal columns to support the weight of the props, 1939.

Even Gene Tierney’s portrait from Laura (1944), stored here, was used again in On the Riviera (1951) and Woman’s World (1954). Over a million items were cataloged for The Egyptian (1954), and many were sold to Paramount for Cecil B. DeMille’s The Ten Commandments (1956). The USS San Pablo gunboat used in The Sand Pebbles (1966)—constructed in Hong Kong under the direction of Boris Leven—was the studio’s largest prop built to date. Actually defined as a hand prop, it was built flat-bottomed like a raft, with a motor to navigate the rivers of Taiwan.

Part of the Victorian furniture collection, 1939.

18th and 19th century European antiques.

The assistant propmaster for The Sand Pebbles was Dennis Parrish, who recalled that Frank Brown ran the prop department then, and Walter Scott ran set dressing. Parrish, who was the first propmaster to get screen credit at Fox for The Flim-Flam Man (1967), also worked on Hello, Dolly! (1969), and literally rounded up an army for Patton (1970). He recalled that the studio was at such a low point when he worked on his favorite Fox project, The Vanishing Point (1971), that it was the only film shooting on the lot. Once again, as during the days of Cleopatra, the commissary was closed and only a coffee wagon in front of the administration building offered refreshments.

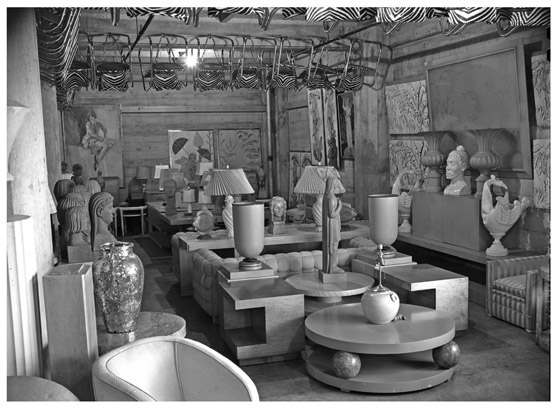

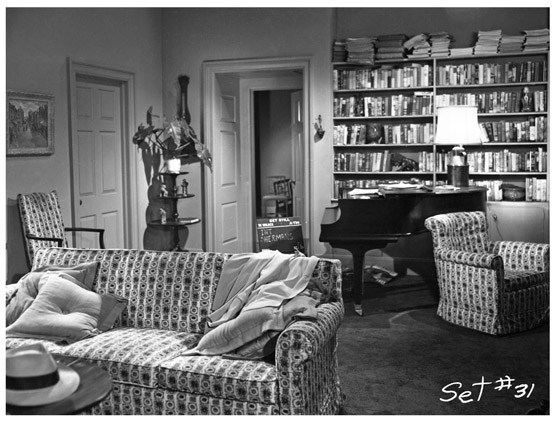

Part of the 1930s modern furniture collection. Look for the modern zebra chairs in the movie nightclubs of the 1930s and 1940s.

More of the Fox prop department. Furniture from every era and every style was collected to fit the needs of Fox productions.

Part of the extensive collection of French antiques that were acquired in Europe.

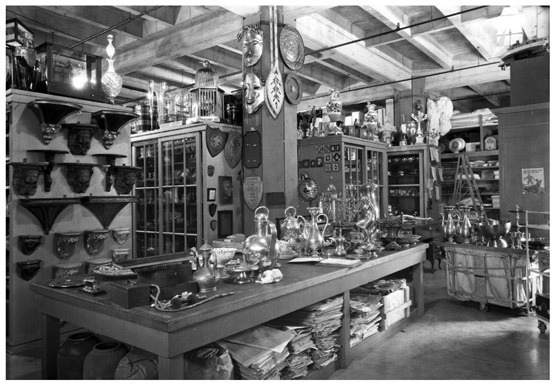

The hand prop department.

Telephones and other electronic equipment. Note the FBC prop microphone— a prophetic prop in that this was decades before Fox created the real Fox Broadcasting Company.

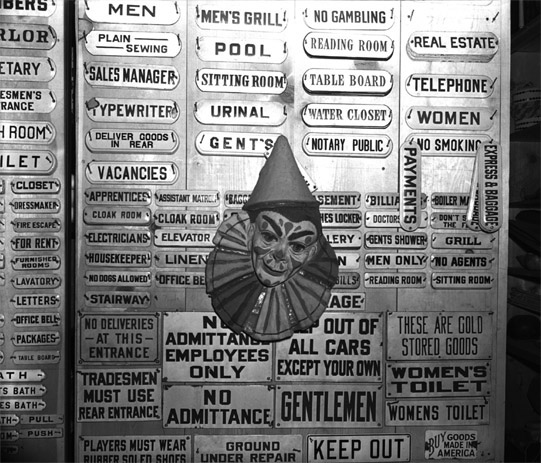

Signs are always important props.

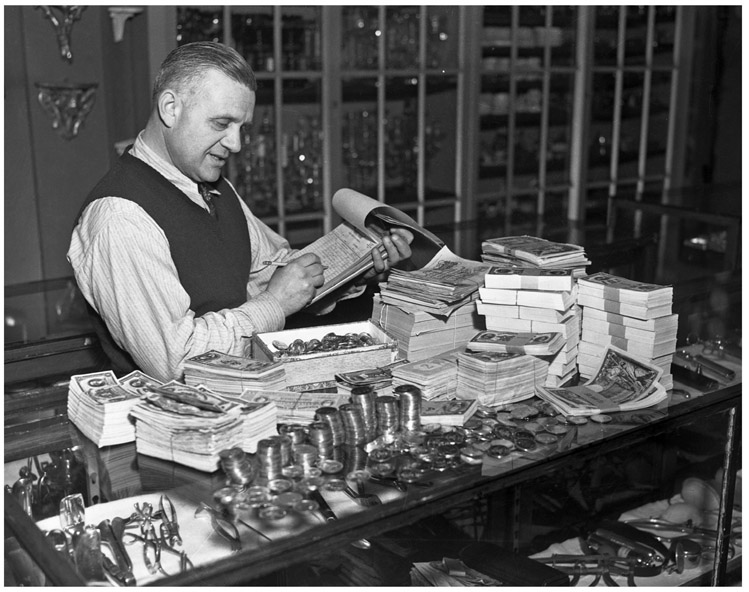

In the days before credit cards, it was necessary to have legitimate foreign currency on hand for movies with international locales, 1938.

The cash-strapped studio auctioned off most of its props—valued at $3.5 million—at Sotheby, Parke-Bernet in 1971. Jane Withers, who had enjoyed playing in the prop house as a child, once spotting a big carved bear and promising to bring him home, bought and stored and therefore rescued much of the memorabilia.

The first Fox auction took place on February 25-28, 1971.

The second Fox auction took place on November 14-21, 1971.

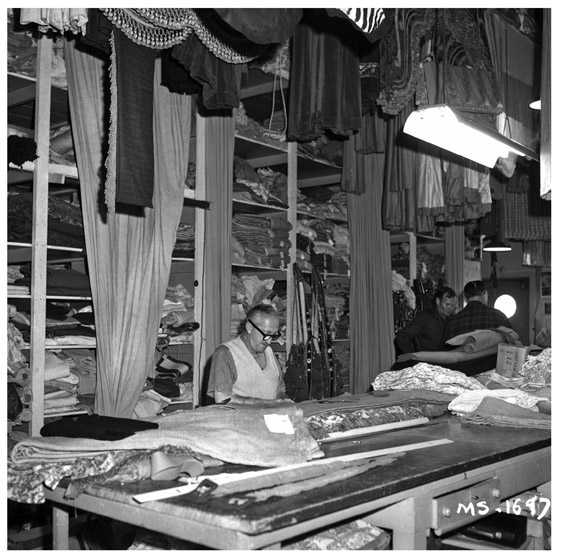

The Drapery Department is still located in the south end of Bldg. 89 where it has been since the 1930s. Here it is as it appeared in the 1960s.

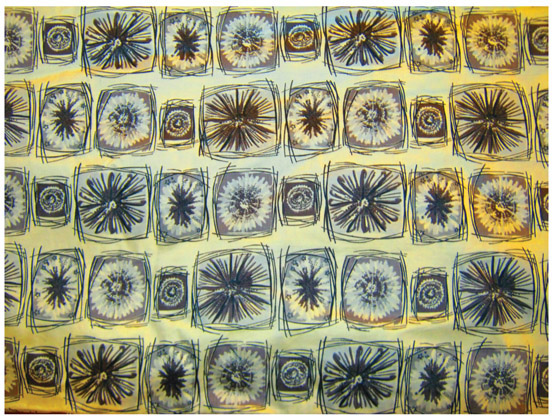

Although the property department continued to operate for another ten years, much of the space here was renovated into offices. The only vestige of the building’s original use are the cement pylons visible inside, built to hold the weight of the props, as well as the huge freight elevator and loading dock. Look for that elevator in Thank You, Mr. Moto (1937). Although the drapery department is still located at the south end of the building, providing custom work for new productions, it got out of the rental business in 2006 and sold off its inventory of draperies, upholstery, and bed linens. Remainders of original fabric used for the couch in The Seven Year Itch (1955) and an original set of curtains from The Sound of Music (1965) are now safely housed in the wardrobe vaults.

Upholstering (and frequent re-upholstering) has always been a major function of the Drapery Department.

Maria’s curtains in The Sound of Music, one of the most famous sets of curtains in movie history, originated here in the Drapery Department.

Fox still has a set of those curtains.

Fox also still has such items as the fabric used for the couch in The Seven Year Itch (1955).

The couch used in The Seven Year Itch (1955), now depicted on Stage Ten, was upholstered here.

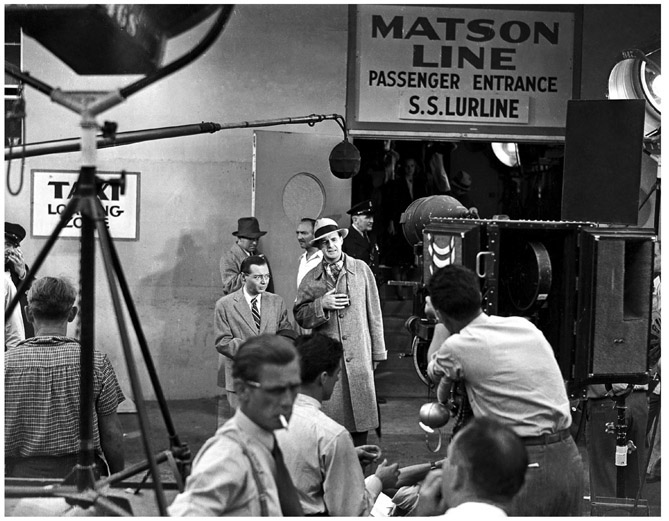

Peter Lorre (no hat) stands on the west side of Bldg. 89 by the truck docks for his scene in Mr. Moto Takes a Vacation (1939).

Three quarters of a century later, Seeley Booth (David Boreanaz), left, stands in the same spot as Peter Lorre in the Bones episode “The Friend in Need.”

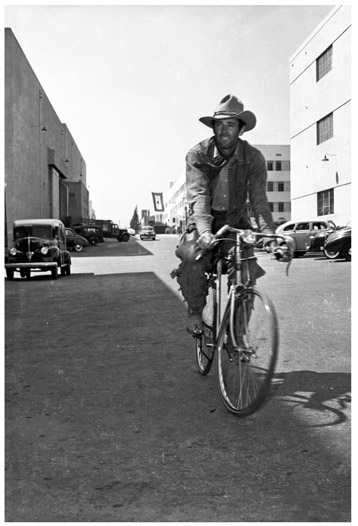

Henry Fonda takes a bicycle ride down Avenue D with Bldg. 89 on the right and Stage Fourteen on the left during the filming of The Ox-Bow Incident (1943).

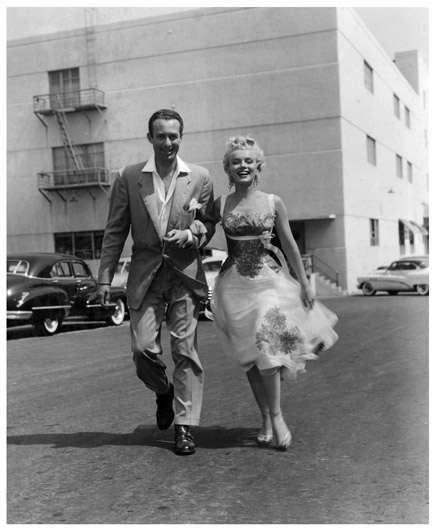

Marilyn Monroe and a friend take a stroll north of Bldg. 89, 1954.

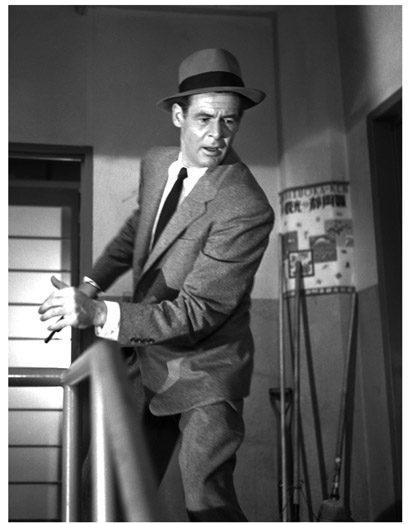

When Robert Ryan ran to the top of a department store roof in Tokyo in House of Bamboo (1954) he was actually running up the stairs of Bldg. 89. One of the buildings signature octagonal columns can be seen on the right.

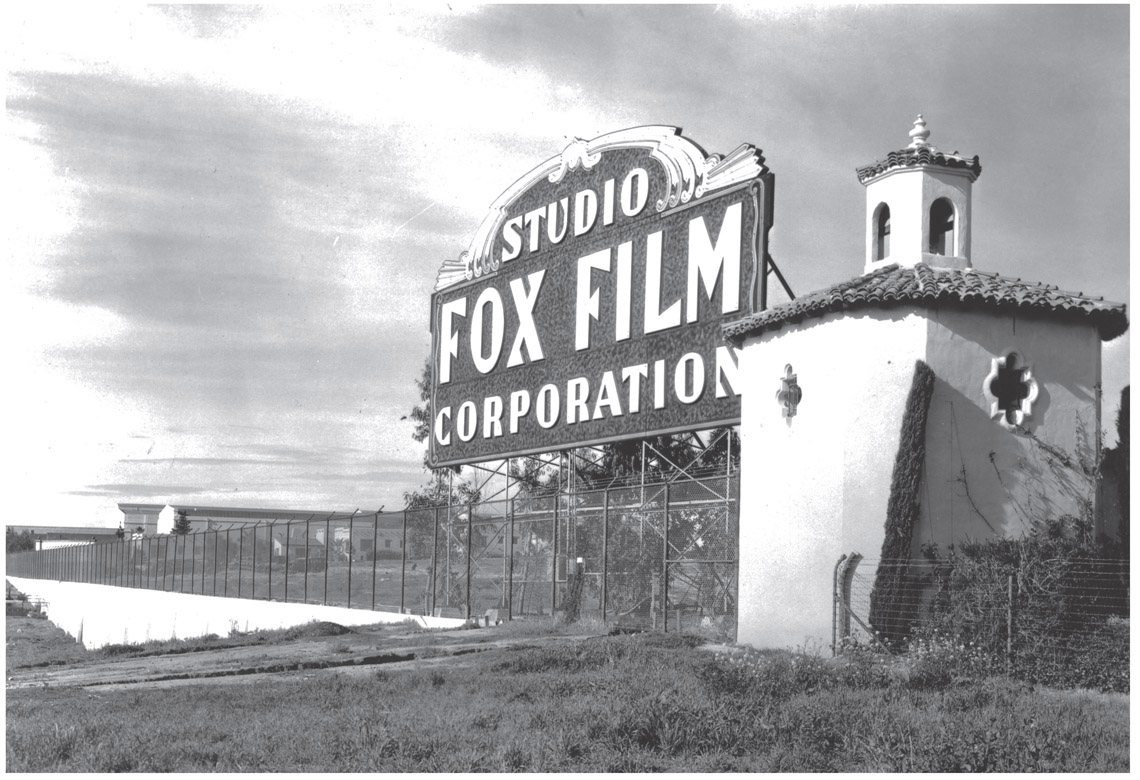

The large neon sign on the southwest corner of the lot on Pico Boulevard near Fox Hills Drive, which was the original access road to the studio’s main entrances on Orton and Tennessee Avenues. The star bungalows (including Will Rogers’ with the chimney) can be seen in the mid-distance with Stages Three, Four and Five rising behind. This is now the site of the Pico West parking structure.

The lovely Spanish Colonial wall was more restrained than the one on Santa Monica Boulevard because this was not built as an official entrance. The water tower on the right belonged to the Hillcrest Country Club.

Detail of the Pico Boulevard wall.

The guard at the gate checked my drive-on [pass], and then he asked, “Have you been on the lot before?” I introduced myself properly; I said I was the former president of the studio. Seriously, whenever I drive on the lot, I can’t help thinking about the great times I had here. We had a lot of fun, which was important.

—Richard Zanuck, 2005

When the studio opened as Movietone City, there was a Spanish Colonial stucco wall here with a decorative tower less elaborate than the one on Santa Monica Boulevard. The wall stretched along Pico Boulevard, just like its counterpart on the north side of the studio. There was a large electric neon sign on the west end of the wall advertising “Fox Hills Studio” that was removed after the merger.

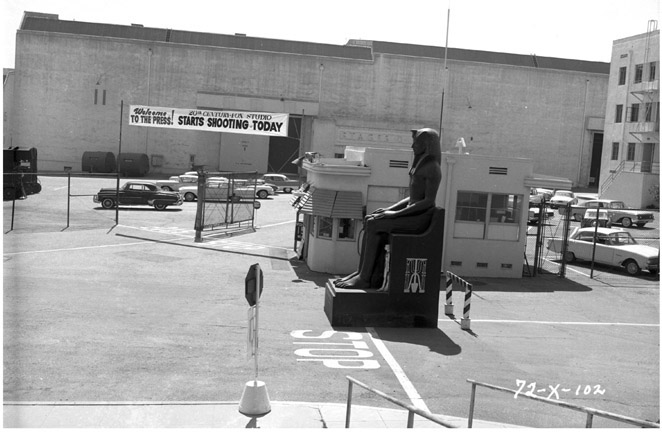

In April of 1936 Joseph Schenck authorized the purchase of 0.79 acre to create a new main entrance to the studio, moving the administrative headquarters from the west side of the lot to the east side with the construction of Bldg. 88. Gate 8 at 10201 Pico Boulevard has been the main entrance ever since. Guard shacks were created: one on the south end of Bldg. 88, and one on the north end. The Pico time office (for employees to punch their cards) was on the north end. The north gate was for employees, while the south gate was for visitors. “Twentieth Century Fox Film Corporation” signage was installed on the east side of Bldg. 89, while the “Twentieth Century Fox” neon sign resembling the famous logo was installed on the roof.

“How far you drove your car into a movie studio was a matter of considerable importance and something that was closely watched by those you worked with,” recalled child star Dick Moore. “At Fox, the main parking area was inside the front gate, tended by guards. To reach the studio, you had to pass through a second gate. If you could drive past the second guard right onto the lot, you knew your option was going to get picked up, or that they liked you at the studio.”

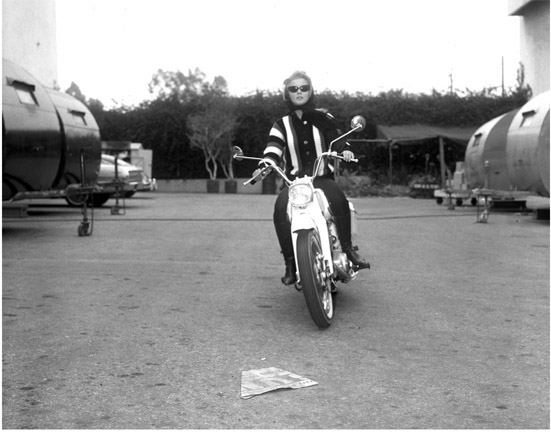

While many movie stars showed up here looking the part—Betty Grable and Marilyn Monroe in red and black Cadillacs respectively—Ann-Margret preferred her motorcycle, and producer Saul David remembered Raquel Welch arriving her first day in a Volkswagen that barely made it.

“Elvis loved going to the studio,” recalled friend Jerry Schilling. “We all loved going to the studio. These poor kids from Memphis who a lot of times did not have enough money to get into a movie theater were now being driven onto the lot in limousines. It was exciting!”

Other than the addition of a large billboard just east of Bldg. 89 that had appeared by the 1960s, Gate 8 remained unchanged until the construction of the Hello, Dolly! set in 1968. The south guardhouse was removed, and once filming was completed, a new, smaller guardhouse was installed. The north guardhouse and Pico time office remained in place, though disguised during filming. Check out the pilot episode of The Fall Guy (1981–86) for a great look at the entrance, still dominated by the Hello, Dolly! (1969) set.

By the early 1970s, the neon sign on Bldg. 89 had been removed. Stage Fourteen got “Twentieth Century Fox Film Corporation” inscribed on its south end, along with a new 1970s “glass dome” logo. That logo was replaced in 1984 with a new one. Toward the end of the decade Gate Eight got a facelift to complement the new Bldg. 100. More of the Dolly street made way for a new guardhouse; a massive, beveled, seventeen-foot-high billboard completed in June 1996, filling the gap between Bldg. 89 and Stage Fourteen, and designed to feature current productions; and a long, low 210-foot cascading fountain along Pico, and four new drive-through portals opened in 1999. The billboard was completed in time to advertise the July 4 release of Independence Day (1996). Since then it has alternated between films and TV shows.

Of course, there are many stories from guards about gatecrashers. Irving “Gibby” Gibbs remembers some who offered money; the would-be actress who insisted that she was late on the set of Greenwich Village (1943) that had already finished shooting; and an ambitious stripper who wanted to work there, since Gypsy Rose Lee did, and even started to perform to prove her point. Ed Conlon recalled a strange fellow who prowled the perimeter of the studio, issuing death threats in a vain attempt to play the lead in The Boston Strangler (1968).

After the successful merger of Fox and Twentieth Century Pictures, the financially robust studio launched a major expansion project that turned the south end of the main lot, previously used for sets, into a site for permanent structures. The plans included a new administration building built on the opposite side of the lot from the original one (Bldg. 1) near Pico Boulevard and, hence, it was decided to make an official entrance here as well. Down came the Spanish wall to make room for Stages 14, 15, and 16 and the new Prop Building (Bldg. 89) with its signage and a new neon sign bearing the new company name.

Closeup of the neon sign on Bldg. 89.

And at night.

The Pico Gate had a long approach with two entrances—one at the south end of Bldg. 88 and one at the north end. Here actor John Payne arrives at the north guardhouse, 1944.

The guardhouse at the south end of Bldg. 88 as it appeared in circa 1962. The north guardhouse is just out of the picture on the right.

View of the south guardhouse and Stages 10 and 11 behind. This view has not been seen since 1968 when the Hello, Dolly! (1969) street was built in front of these stages. The large statue of Rameses greeted visitors to promote Cleopatra (1963).

Ann-Margret, in between Bldg. 89 and Stage 14, gets ready to exit the Pico Gate on her motorcycle during the filming of The Pleasure Seekers (1964). The parked “honey wagons” were used as trailers for movie stars on set for decades.

The north guardhouse (left) and the Pico Time Office (right) where employees clocked in and out.

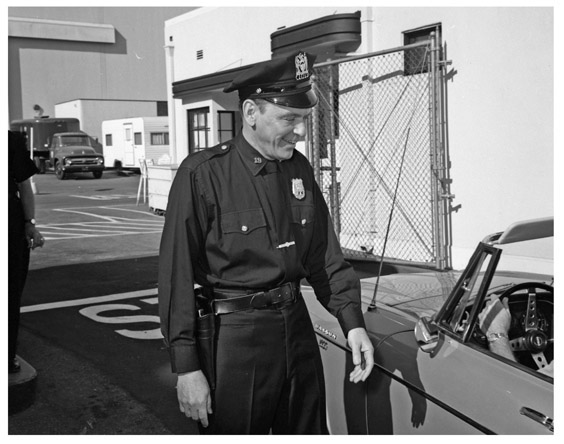

Frank Sinatra gets some real life experience in law enforcement while filming The Detective (1968). The Pico Time Office is at right, the north guardhouse at left, and Stage 21 is behind.

During the Los Angeles riots in 1992, Rupert Murdoch coolly lunched in the commissary with TV agents despite threats to the studio and vandalism to this gate. At five the next morning, Murdoch showed up at Fox’s KTTV-TV studios with coffee and bagels for the beleaguered news crews.

The neon sign on Bldg. 89 was altered to advertise Hello, Dolly! (1969) (glimpses of the set can be seen).

When one of the decades-old ficus trees lining Pico Boulevard dropped a branch into the street one morning in 2013, the decision was made to replace them with palms. With the south ends of Stages Fourteen, Fifteen, and Sixteen now visible, the studio resurrected the practice of advertising upcoming films and televisions shows on them in late December. Another significant change was the installation of the “Fox Studios” signage above the drive-in entrance. Although “Fox Studios” was chosen to reflect all the current divisions of the company, it certainly acts as a throwback to the days before the Twentieth Century Fox merger, and a reminder of the founder who started it all.

A new logo and a new pylon on Pico Boulevard.

Down with the old and up with the new Fox logo in 1984.

The Pico entrance advertising Aliens (1986). The large fountain is a remnant of the Hello, Dolly! (1969) set while the new Fox Plaza tower rises in the distance.

A new beveled billboard was installed between Bldg. 89 and Stage 14 to advertise the summer block-buster Independence Day (1996).

Large ficus trees had grown for decades along the north side of Pico Boulevard matching those on the south side of the street. In 2013 a large branch fell off one of the massive trees into the road but luckily no one was harmed. This prompted the studio to replace the decaying trees with palm trees. With new visibility, the studio revived the century-old tradition of advertising movies on the sides of soundstages.

Gene Tierney takes a call during the filming of China Girl (1942). This “phone call on set” shot was standard publicity fare for years—almost every movie star had a similar shot taken at one point or another while working at Fox. This one stands out because it actually appears to be a candid.