2

THE BEDFORD AVENUE GANG

The generation coming of age in New York in the new century, many of them children and grandchildren of immigrants, were rebelling against what they saw as a restrictive code of behavior. Much like the baby boomers who grew up in the 1960s, the turn-of-the-century sons and daughters of the prosperous middle class, children of privilege, wanted to do things a different way from the generations before them. They had their own music (ragtime), their own clothing styles (colored vests for the boys, “rainy-day” dresses that revealed girls’ ankles, and automobile coats for both).1 They frequented forbidden dance halls; hung out at Coney Island; drank beer, gin rickeys, and martini cocktails at roadhouses; and had sex—all while still in their teens.

FLORENCE BURNS

Even by her own admission, Florence Wallace Burns was out of control from an early age. Born on Easter Sunday, April 9, 1882, to the daughter of strict German immigrants and the son of strict Scottish immigrants, Florence early on adopted the code of her peers: to do what she wanted when she wanted and with whom she wanted. Her parents were at a loss as to what to do with her.2

Frederick Burns, Florence’s father, was a successful insurance broker in Manhattan, but his real claim to fame was as an announcer of athletic events—track, field, walking contests, bicycle racing, and just about anything under the auspices of the Amateur Athletic Union. He was widely known and respected as “the silver-tongued Fred Burns” and kept a .32-caliber starter’s pistol in the home for those occasions when he was responsible for signaling the beginning of an event as well as announcing it. (Both Florence and her mother were excellent markswomen with this pistol and had even won prizes for target shooting.)3

Florence Burns (New York World, from a portrait)

Mrs. Burns was the former Henrietta Von derBosch. Her father, Wilhelm Friedrich Von derBosch, had been one of John Roebling’s chief engineers in the construction of the Brooklyn Bridge, completed in 1883 when Florence was one year old.4

Florence did not do well in school. For one thing, she was lazy. For another, she was more interested in boys than in her studies. Finally, although she was very beautiful and desirable, the many young men she dated declared her ultimately boring and a dullard when the physical attraction wore off. Consequently, although most of her friends, both male and female, attended the local high schools—primarily Erasmus and the Brooklyn Boys’ High School—Florence did not go beyond the eighth grade, although she once made a brief attempt at a business school.5

Florence’s first serious “beau” was Harold Leon “Harry” Theall, son of a wealthy Brooklyn druggist. While he was at Erasmus High School, they dated when she was sixteen and Harry was a year older, but then when he broke it off with her—coming to the same conclusion as all Flo’s boyfriends eventually did, that she was dull—she alarmed him and his family with behavior that today would qualify as stalking. There were rumors that she had threatened to kill him if he did not marry her, but these may have been only rumors. However, when an interviewer asked Harry’s father about it, he never denied it. Nevertheless, the Thealls solved the problem by sending their son to a prep school “out West” (Wisconsin!), after which Harry enrolled in the Yale Law School as a special student two years later.6

Florence chafed against what she saw as her parents’ and teachers’ old-fashioned rules and restrictions. “My mother should have been born a century ago,” she complained. Her father once got so frustrated with her that he pulled her across a room by her hair. As well as wanting their two daughters (Gladys was born in 1885) to be well-behaved, genteel girls, Mr. and Mrs. Burns were also keenly aware of the opinions of their neighbors in Flatbush. Florence had gotten kicked out of the Sheepshead Bay Race Track at Coney Island for smoking in public and may have also gotten kicked out of school. She was hanging out with what was considered a wild crowd and was the subject of unflattering gossip. One time, Fred Burns got a private detective, John Walsh, to look for his errant daughter. Walsh found her at Coney Island at a dancing pavilion and persuaded her to go to an aunt’s house in Manhattan, from which she was taken to her home in Brooklyn.7

In an effort to stop the gossip and get Florence away from the bad influence of her friends, Fred Burns took her to Montreal and enrolled her in a convent school. She was not happy there and claimed the other girls made fun of her (she did not say why), so she ran away, somehow making her way back to Brooklyn on her own. After that, she was sent to a farm in New Jersey, possibly owned by a relative, as both Burnses had family in that state. However, she horsewhipped the farmer and ran away from there too.8

Often confined by her parents to her bedroom, Florence told a friend that she could not bear it anymore and had attempted to end her life by blowing out the pilot light on the gas fixtures.9

By the age of seventeen, Florence was heavily involved with the Bedford Avenue Gang, sometimes referred to as the Bedford Avenue Hounds, running with them nearly every day and most nights.10 If the boys did not come calling for her on a given night, she was just wild with restlessness and anxiety. From then on, the Bedford Gang was her new family, the place where she felt most comfortable, living the kind of life she had always wanted, unfettered by the tired old ethics of the Victorian-era middle class. It was a new century, and it called for a new set of standards.11

THE BEDFORD AVENUE GANG

Although the neighborhood of Bedford and Stuyvesant Avenues would achieve infamy much later in the century for its racial violence, it was an entirely different kind of gang that preyed on people in the early 1900s. The neighborhood at that time was comprised of gorgeously ornate row houses and stand-alones owned by upper-middle-class professionals and business owners, predominantly German and Irish immigrants who had been successful in the New World. To their great dismay, the marauding gang was made up of their own sons, with their daughters following the gang as adoring and complicit groupies.

The Bedford Avenue Gang’s main goal was to get money from unsuspecting citizens, primarily shopkeepers. It did not matter that most of these young men had plenty of spending money from their parents. It was more for the thrill of the con, as well as to finance their love of fine and fancy clothing.

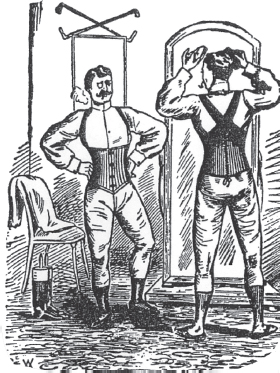

Gang members were identifiable by their “uniforms” and hairstyles: their hair was parted very low on the left side; they wore diamonds and corsets(!), brightly colored (usually red, while the still-too-young gang aspirants adopted pink) vests, and long spike-tailed overcoats that resembled those worn by a circus ringmaster. Most of them carried canes as thick as baseball bats, which could also be used as cudgels. Theodore Burris, Walter Brooks’s best friend, walked about with an intimidating Great Dane to go with his Great Cane.

One of their favorite scams was for one of them to go into a haberdashery, pass himself off as the son of a prominent customer, and, using a forged order, commission a suit or an overcoat to be delivered to the customer’s address. Then, when the item was being delivered, the young man would waylay the delivery boy and take possession of the garment. Walter Brooks, the shooting victim, was one of the gang members who had done this at least once.

Another favorite trick was to represent themselves as advertising men for newspapers, magazines, and programs to be sold at sporting events, then approach businesses to procure ads for these publications, some of which were nonexistent, and take the payment for them. Needless to say, neither the ad appeared nor the money delivered to the publication.

Several members of the Bedford Gang would invite a “sucker” to have dinner with them at a fancy restaurant, order expensive food and drinks, then quietly slip away one by one on various pretexts until only the hapless mark was left to pay the bill. When Walter Brooks and his friends pulled this scam on an unsuspecting young man at Brooklyn’s prestigious Hotel St. George, the maître d’ luckily was able to identify most of the gang members. He called their fathers and told them that, if the bill were not paid, he would have their sons arrested. The bill got paid.

From an ad for men’s corsets, 1893 (University of Virginia Historical Collections at the Claude Moore Health Sciences Library)

Another version of this scam, pulled twice on the same ice cream shop in the summer of 1901, was for the gang to go in and order ice cream, eat it on the premises, then drift out as one of them approached the counter to pay. Naturally, the clerk assumed that this young man was paying for the group he had been with, but he paid only for his own ice cream, claiming no responsibility for his friends. When the store manager later came across some of these scoundrels on a street corner, he gave them a few black eyes.

Gang members passed bad checks, forged others, cheated at cards, stole cars for joyriding, started fights, and shoplifted. Theodore Burris, Walter Brooks’s aforementioned best friend, could well serve as the role model for the Bedford Avenue Gang.12 He was a one-man crime wave. Tall and muscular at just over six feet, Burris did not hesitate to take on either policemen or civilians. He once punched a physician he saw on the street, a perfect stranger to him, because he didn’t like his looks: the man was small and had a turned-up nose. The only son of a millionaire stockbroker, Ted seemed to have gone somewhat berserk after he graduated from high school in about 1898 and went on a ten-year crime spree. A veritable Peter Pan, he refused to do any kind of honest labor. Instead, he used his generous allowance—much of it provided by his adoring mother over the wishes of his fed-up father—to frequent racetracks and nightclubs and to indulge in affairs with married women. His father was so disgusted and so frustrated that he had Ted arrested for vagrancy, a charge young Burris smoothly talked his way out of, as he did every other charge against him.

Burris stole money, rings, cars, and once even a prize French bulldog worth $1,000. He impersonated other society men and passed bad checks using their names. He hit a hotel detective over the head with a blackjack, or maybe his “cane,” then robbed him. When a police officer arrested him for larceny, Ted assaulted him and hurt him quite badly. It took five other officers to subdue him, whereupon he boasted that he had been a tackle on the Cornell football team before leaving college in his freshman year, which is why he could fight so well. But it was just another one of his made-up stories: neither Cornell nor Harvard, which another newspaper reported as the school he had briefly gone to, had ever enrolled him.13

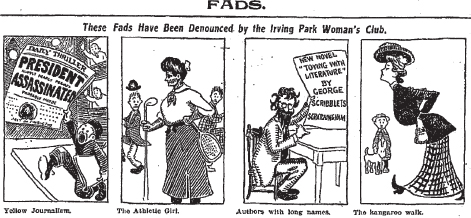

The adjectives most frequently used to describe Theodore Burris were “urbane,” “jaunty,” and “imperturbable.” He had a sort of ebullient “kangaroo walk,” a fad practiced mostly by young women, which required thrusting the upper body forward with the head held high and proceeding forward in a “hoppy, springing stride and swinging arms.”14 This arrogant insouciance so enraged one judge that he yelled at Ted to “walk straight,” a command the latter completely ignored. He was constantly defended and bailed out by his sisters, his mother, his brother-in-law, his friends, and even some of his victims, who refused to press charges. The prominence of his family made prosecutors reluctant to charge him and judges reluctant to sentence him. In short, Theodore Burris was the very epitome of what his fellow Bedford Gang members aspired to be.

Yet, despite Burris’s recklessness, he confessed that he made a conscious decision to stay away from Florence Burns because he knew she would cause him trouble.

Probably the most egregious activity of the Bedford Avenue Gang was “ruining” as many young women as possible, either through seduction, date rape after putting chloral hydrate in drinks, or gang rape, then bragging about their exploits. In many instances, the girls themselves were willing accomplices because these boys belonged to prominent, wealthy families. Gang members took the girls to Coney Island or met them in so-called “houses of assignation,” which they rented in Brooklyn. Harry Casey had his own yacht, which the gang used for sexual purposes. Neither the boys nor the girls had learned a lesson from the death of Jennie Bosschieter in nearby Paterson, New Jersey.15

Cartoon showing the “kangaroo walk” fad (Chicago Tribune, reprinted in www.newspapers.com and used with permission from www.Ancestry.com)

THE MURDER OF JENNIE BOSSCHIETER

Seventeen-year-old Jennie Bosschieter, a millworker’s daughter, enjoyed dating and hanging out with the sons of Paterson’s upper-class families. An immigrant from the Netherlands and a member of the laboring class, Jennie was very aware of the advantage to herself and her family that such a marriage would bring. She flirted with the young men, as did the other mill girls, and accepted their invitations to join them at restaurants and saloons. Although not a gang in the sense of the Bedford Avenue Hounds, four of Paterson’s scions—Andy Campbell, Billy Death (pronounced “Deeth”), George Kerr, and Walter McAlister—spent a lot of time together in these establishments and targeted the mill girls as their prey.

One night in October 1900, they persuaded Jennie Bosschieter to join them for drinks and slipped some chloral hydrate into her absinthe, using more of the drug than usual. They hailed a cab and carried the unconscious teenager out a side door, then instructed the cab driver to take them to a remote location. There, they all took turns raping her. Back in the cab, they could not rouse her, so they had the driver take them to a doctor’s house. The doctor informed them that the girl was dead, whereupon they got back in the cab and dumped the body by the side of the road. The cab driver turned them in and directed police to the doctor as well. The quartet had the typical mindset of the upper classes that servants and laborers were deaf, dumb, and blind.

What killed Jennie Bosschieter was an overdose of chloral hydrate. The citizens of Paterson were divided as to whether these sons of upstanding, prominent families should go to prison, and the victim was painted in the media and in local gossip as “a girl no better than she should be” in the parlance of the day. All four were found guilty after one of them ultimately confessed the whole thing, and all served fifteen years. The judge was sorry he could not have imposed the death sentence on them even though the jury had recommended mercy, but he made it plain that he thought they deserved it.

CONEY ISLAND AND BADER’S ROAD HOUSE

Eighteen-year-old Florence Burns willingly succumbed to seduction in February 1901 by a twenty-five-year-old divorced man, Edward Cole Watson Jr. Watson was known as “the handsomest man in Brooklyn,” a title Florence said he would rather have than president of the United States. He was a gang member whose own father had testified against him in the 1899 divorce hearing because he knew that “Handsome Ed” had cheated on his wife of two years. Word of Florence’s fall from grace got out to her parents, and, horrified by both their daughter’s behavior and the resultant neighborhood gossip, they threw her out of the house. For a while, that was fine with Florence.16

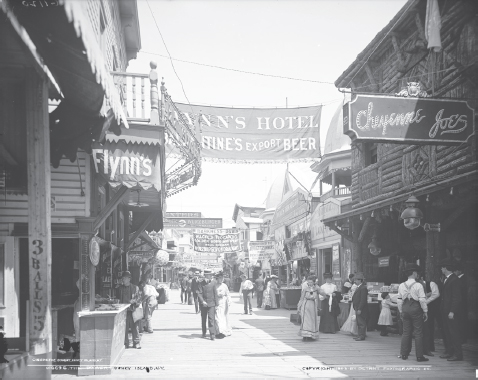

For Florence and the Bedford Avenue Gang, their base of operations was Coney Island and, by extension, nearby Bader’s Road House. Although Coney Island had been in existence for many years, it was not until its rebirth in 1895 that it was able to overcome its bad reputation as a dangerous and criminal place with the establishment of a series of family-friendly amusement parks. Moreover, the growing number of affordable transportation options brought a diverse crowd of patrons from the other boroughs besides Brooklyn. In 1895, a nickel trolley carried them to the gates, and an express train from the Brooklyn Bridge could get there in a little over a half hour. For all classes and all ages, Coney Island was eminently accessible and affordable for a quick trip after a hard workday or a more extended visit on a weekend.

Coney Island was attractive because it invited its patrons to relax the strict standards of interaction, courtship, decorum, and clothing. Strangers mingled with each other on the beaches in “bathing costumes” and struck up conversations without having been introduced. For young men and women especially, Coney Island was a place to escape adult supervision, and its rides provided opportunities for close physical contact with each other. Just to join the exuberant crowds on the promenades and boardwalks was a powerful attraction even for those who had no money to spend. Florence Burns’s friends commented that it was a rare day when she was not seen on the boardwalk in the summer of 1901. And when she and her friends were not at Coney Island, they were at Bader’s Road House.17

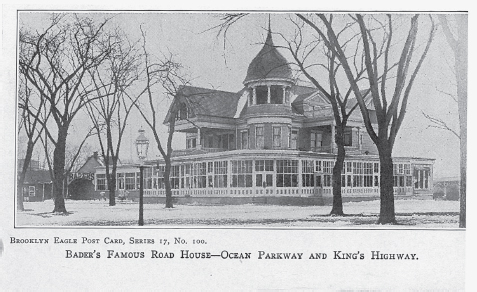

The proprietor of Bader’s Road House was George D. Bader, born in Germany in 1855. Bader had positioned his hotel/bar/restaurant in an extremely advantageous location: on Ocean Parkway at the juncture of the Coney Island concourse, near a railroad station. The boulevard was a popular one with cyclists, horsemen, and carriages, and Bader made sure to accommodate them with racks for bicycles and sheds for horses. The elegantly appealing hotel could house fifty guests, and often did, but it also did a booming business in serving Coney Island day visitors stopping by for a meal or a drink.

Although Bader’s Road House was strategically located and would have been successful in any event, George Bader’s larger personality and his eye for promotion were probably what put him over the top. Bader’s was a stopping point along the way for bicycle tours and also for a contest as to which would be the first sleigh to arrive at each roadhouse in winter. The prize was a magnum of champagne.

George Bader greeted his guests with hearty enthusiasm and often insisted on their ordering a dish he wanted them to try. Few could resist him. One time, a wealthy thirty-eight-year-old customer arrived in his automobile “runabout” (an early version of the roadster) with his twenty-four-year-old fiancée. They had been engaged for some time and the fiancée must have been wondering when a date would be set. George Bader took care of that for her. He asked, “Why not get married here and now?” Then he got in the customer’s runabout, dragged a minister out of a nearby formal dinner to perform the ceremony, whisked him back to the dinner afterward, and sent the newlyweds on their way to Niagara Falls for their honeymoon. The bride had just enough time to send her family a telegram announcing the marriage.18

Bader’s was not the only hangout for the Bedford Avenue Gang and their groupies—among them Harry Casey, Samuel Maddox (the son of a judge and himself a law student), Bud Kennahan, Joe Wilson, Florence Burns, George Williams, Ed Watson, Mabel Cooper, Ruth Dunne, William “Max” Finck, Grace von Brocklin, Theodore Burris, George Jackson, and Walter Brooks—but it was probably their favorite. There does not seem to have been any kind of age restriction on alcohol, as these seventeen- and eighteen-year-olds were able to order beer, wine, gin rickeys and fizzes, martini cocktails, and whatever else they wanted. Florence’s alcohol of choice was always gin, with an occasional beer on a hot day.

Harry Casey, wearing the fancy “swallowtail” coat preferred by the Bedford Gang (New York World)

Florence had moved on from “Handsome Ed” Watson to Joe Wilson, and, by August 1901, her current beau was Bedford Gang leader Harry Casey, the charming nineteen-year-old ne’er-do-well son of a millionaire Irish immigrant named Richard Casey. Harry Casey, like his friend Theodore Burris, had charisma in abundance and used it to his advantage. The Caseys had a summer home in the Catskills, where Harry entertained many of his city friends and charmed the locals with his comedy routines and exaggerated accounts of derring-do. He was also well on his way to being an alcoholic.19

Like the father of Theodore Burris, Mr. Casey was fed up with his son’s lifestyle. Harry liked fine clothes and charged his frequent purchases to his father’s account, causing the elder Casey to publish a notice in the newspaper that he would no longer be responsible for his son’s debts.20

Before there was such a crime as joyriding, Harry stole cars for a wild ride, then would leave them in the approximate vicinity from where he had taken them. Despite being arrested, he served no time, as the owners had suffered no permanent loss of their vehicles and did not wish to press charges against the son of the well-known and well-to-do president of the Whiskey Trust.21

Early one morning, after a night of revelry, Harry Casey and several of his male friends were whooping it up in the Bedford area. Harry had a pistol and drunkenly shot out some street lights. While wrestling with a friend for possession of the gun, he pulled the trigger and shot the other man in the hand. Harry was charged with felonious assault, but the wound was not serious and the friend refused to prosecute.22

By the summer of 1901, Harry was getting tired of Florence and looking for a way to end the relationship without a lot of hysterics on her part, which she was prone to when she did not get her way. He found his opportunity one day at Bader’s when he introduced her to fellow gang member Walter Brooks.