9

THE COURT OF SPECIAL SESSIONS

New York City’s Court of Special Sessions, replaced in 1962 by the New York City Criminal Court, was the equivalent of a Municipal Court, the venue for misdemeanor criminal cases and civil cases valued at under a certain dollar amount. Although Florence Burns would be subject to the death penalty if convicted of murder, she had not been formally charged as yet and this was not a trial, even though she was under arrest. A felony trial would be held in the Court of General Sessions, like today’s Superior Court, but the hearing to determine whether that trial would take place was held in the inferior court.

Magistrate Cornell had agreed to this hearing, in lieu of one in front of the grand jury, but because he was an acquaintance of Fred Burns, he recused himself from presiding over it. However, he did not let his friendship with Burns prevent him from denying bail for his daughter. Still, this was an enormous concession to a murder suspect.1

Florence’s future would be determined by the judge who had been recently appointed to take the place of William Travers Jerome on the court after Jerome’s recent election as district attorney: thirty-six-year-old Julius Mayer, “a stickler for the dignity of the court,” who would be described in his later career as “more a Czar than a Judge.” Lawyers who would appear before him over the course of his career would remember one of his most frequent remarks as, “Come to the point and be brief.”2

During the Burns hearing, Judge Mayer was incensed at the circus-like atmosphere that frequently attended it, with spectators coming and going at will, laughing and talking and eating, and generally acting as if they were at an entertainment—which, of course, they were, as high-profile murder cases were great sources of public enjoyment. This would cause the judge to stop the proceedings and issue an ultimatum: Sit still, be quiet, or leave. At one point, frustrated by his inability to effect any change in spectator behavior, he issued an order to his deputies that no one could come in or go out while there was a witness on the stand. This, at least, cut down on the commotion during testimony caused by curiosity-seekers who were constantly entering, looking around for fifteen or twenty minutes, then leaving.3

Although William Travers Jerome was in charge of the Burns case, he spent much of his time interviewing witnesses in an attempt to find a “smoking gun” that would link Florence to the Glen Island Hotel at the time Walter Brooks was shot.4 Consequently, much of the day-to-day testimony was handled by Assistant DA George Schurman. Of the many potential witnesses brought before Jerome, only a small percentage testified under oath at the hearing. This was for several reasons: first of all, Jerome did not want to reveal all his evidence at the hearing; second, some of the witnesses were not credible; and third, some of them seem to have refused to testify under oath, either because they were not telling the truth or because they did not want the notoriety that public testimony would bring. It is interesting to note that of all the witnesses Foster Backus procured on behalf of Florence, not one testified in court. Of course, it was not necessary, as the defense had no obligations at this hearing, but it would seem that if any of them had convincing exculpatory evidence, Backus would have insisted that it be presented.

However, many of the witnesses’ names and their testimony, albeit unsworn, leaked out to the press, which dutifully printed it. In fact, the press was so aggressive in pursuing witnesses for statements that when Walter’s former fiancée Charlotte Eaton and her sister Edith wanted to leave, a detective had them climb out a window in the courthouse, then onto a roof ledge in ankle-deep snow to inch their way to another window, which would in turn lead them to a back entrance unhampered by the pesky press.5

Always aware of the many thousands of people who would not be attending the court proceedings, reporters described everything: the behavior, dress, poses, and physical characteristics of witnesses and spectators alike. If you were a resident of New York City in 1902, you would feel that you had been in the courtroom yourself. For example, you would read that Florence’s outfit for court on February 22 consisted of a “black velvet Russian blouse with tiny silver dots, a black skirt, a belt with a gilt buckle, a big black picture hat, white ruching about her neck, black suede gloves, and a red and white enamel winged Mercury’s-foot pin in her blouse.” When she first arrived in court, she was wearing a veil and a short jacket, both of which she promptly removed.6

Florence’s various poses were also the subject of attention. She yawned a lot, which gave the impression of complete indifference, even though yawning can also be a sign of nervousness. She put her elbows on the table, rested her chin in her palms, or spread her arms on the chairbacks on either side of her—more the behavior of a restless child than that of a young woman facing the death penalty. She claimed to hate being “stared at by all the fools who crowd into the court-room,” she told a World reporter, then, pointing out two young policemen who were watching the conversation, said, “There are two fools staring at me now.”7

The most frequent attendees at murder trials in the Victorian and Gilded Ages were women, and reporters commented on their numbers, their behavior, their looks, and sometimes interjected opinions as to whether they should even be there instead of at home getting their husbands’ dinners. A Brooklyn Eagle reporter ruminated on the different types of women at the Burns hearing, which devolved over the weeks from a “typewriters’ gathering” to an “old maids’ convention” to a “soubrettes’ show.” The latter category featured “peroxided” actresses from the local theaters.8 The women arrived each morning, long before the doors opened, and offered as much as five dollars for an admission card. The admission card requirement was installed by Judge Mayer to manage the attendance, but these were free, to be issued to anyone with a valid connection to the case. And when they were gone, they were gone.9

Harry Casey and his Bedford Gang cohorts “dressed in the very extreme of fashion and appeared to enjoy the situation thoroughly.” Casey and “other sartorial wonders” were “all clad in most irreproachable garb.” But Casey, described as a “gilded youth,” angered observers with his bragging and bravado in court. He gave copies of his picture to the reporters and told everyone that he lived up to his nickname of “Handsome Harry,” as his good looks had been the ruin of many a young woman. Some listeners were tempted to beat him up for this, and for the unprintable language used by Casey and the other boys in discussing the women they had seduced.10

The Bedford Avenue Gang had a field day, dressed in their standard outfits and preening in court over their importance in the case. Scam artists par excellence, they had gone to a newspaper office and offered to sell them a new photo of Florence Burns for twenty-five dollars, but the sketch artist recognized it as that of a local actress known as “Pink Pajama Girl,” whose photo was selling for mere pennies. Undaunted, our lads tried again at another newspaper, this time successfully, as that sketch artist was obviously unfamiliar with “Pink Pajama Girl.”11

EXPOSING THE BEDFORD AVENUE GANG

The Bedford Avenue Gang got their comeuppance in a series of articles in which Foster Backus’s brother Erastus, a detective with the Kings County Court, revealed what he knew about their activities, and an anonymous member of the gang gave out the salacious details of orgies, thievery, and confidence games.12 (The reporter writing these articles had to clean up the language of both the informant and Det. Erastus Backus, as both were fairly profane.)

This informant claimed that the number of young women who were hanging out with the gang (“and you know what that means,” he confided, hinting at sexual activity) was five times the number of young men. They all knew Walter Brooks and Florence Burns and “there wasn’t a member of the gang who was not as well acquainted with her as was Brooks.” He recounted that a young woman in the grandstand at the Aqueduct Race Track was approached by seven gang members she knew. They took her out to one of the stables and “held a wild and shameful orgie [sic].” It was not clear whether this was voluntary on the young woman’s part. Another time, five of the gang members took a girl to a Bedford Avenue pool hall and “indulged in revels which would have put a Nero to blush.” Again, there is no indication as to whether this was a gang rape, although the informant commented that “there is an absolute absence of any moral standard among the young women.”

After the first article appeared, the Bedford Gang members were worried about this exposure and met in a saloon to discuss what should be done. “Who has been peaching?” they wondered. The decision was made that from then on, they should not admit to knowing Florence Burns at all and that they only knew Walter Brooks by sight. “And the one who opens his head again gets his roof blown off.”

Many readers were thankful to the Eagle for the exposé, which they hoped would stop the outrageous behavior and be a wake-up call to clueless parents. Backus went even further: He had a list of sixteen boys under the age of seventeen, all with criminal records, and all having respectable parents, many of them wealthy. If there were to be one more robbery or fake purchasing or other gang transgression, he would give his list to the Eagle for printing.

THE ISSUES

In order to have Florence Burns bound over for trial, the prosecution would need to prove that she intentionally killed Walter Brooks—not “beyond a reasonable doubt” that she did it, but “more likely than not” that she did so—and that the state had probable cause to proceed with a trial.

Anyone familiar with courtroom dramas on television knows the phrase “means, motive, and opportunity,” the establishment of which can result in a verdict of guilty for the prosecution. But what do these words mean in legal terms? Means is not just access to the murder weapon but the ability to use it. If it is determined that the victim was killed with a heavy sledgehammer, then it is not likely that a frail, arthritic, eighty-year-old woman would have the strength to wield it effectively, despite her having access to it. In Florence’s case, the prosecution would have to prove that she had access to the .32-caliber pistol used to kill Walter and that she knew how to use it.

Motive is the one thing that everyone, especially a jury, wants to know: “Why was this victim killed?” Yet, it is not necessary for a criminal case. An 1897 California Supreme Court case still cited today, The People v. Durrant, held that the ways of the human heart are boundless and it is not always possible to divine an individual’s motive. It would be an undue burden to require that a prosecution do so.13 Yet, prosecutors ignore motive at their peril. Notwithstanding its being legally unnecessary, motive is critical to proving guilt to a jury, even if it has to be postulated: Why would Florence kill the man she claimed she loved even more than her parents?

Opportunity is the proximity to the scene of the crime at the time of death, or (in the case of a poisoning or a hired hit) the ability to effect the chain of events that results in the victim’s death. This is where alibi comes in—to place a suspect too physically far away for travel, or seen to be in a different place, however near, at the time of the murder, or having no access to the poison used. Hence, the importance of placing Flo at or near the Glen Island Hotel between 9:00 and 11:00 P.M. on February 14.

GEORGE WASHINGTON

The most critical witness for the prosecution was the Glen Island bellhop, George Washington, who had seen the woman with Walter Brooks that night. Even though Washington was a young newlywed, he was treated as a child on the stand. For example, on February 22, Backus, in a condescending tone, reminded the witness of the truthfulness of his namesake, whose birthday it was that day, and so he must be sure to tell the truth. While everyone else in the courtroom found this humorous, Washington did not. He was never addressed as Mr. Washington, but as George. He was never referred to without race descriptors: Negro, mulatto, copper-colored, “little and yellow as bright copper”; and never as a man, but as a boy. Yet, Washington was a sharp observer, and although he had a slight stutter, he was an articulate and thoughtful witness on the stand.14

Although George Washington fretted about not being able to support his wife because of the court obligations that took him away from his job, he took those obligations very seriously. He made sure that he understood each question and thought about his answer before speaking. If he were asked to identify someone in the courtroom, he stood up and pointed at the individual.15

During his testimony, Washington fell prey to a standard (and still used) trial attorney’s device of breaking down a witness’s estimate of the duration of time. The bellhop had said that, upon arrival in Room 12 and after lighting the gas for “J. Wilson and wife,” he conversed with the woman “for two or three minutes” as to any other needs she might have. At this point, she had lifted her veil, so that he got a good look at her face, and this was critical in placing Florence Burns at the scene. Judge Mayer, in what would normally be the defense attorney’s role, asked Washington to sit silently until the same amount of time passed as that in the hotel room as he looked at the woman. It turned out to be thirty seconds instead of two or three minutes—still a long time to be looking at something, although it suffers by comparison.16

However, Washington had made a critical error, subject to misinterpretation, when he spoke to responding police officers at the Glen Island Hotel on February 15. In his identification of the woman who had accompanied Walter Brooks to Room 12 the night before, he stated that she “was not a clear white woman,” which most people—especially Foster Backus—took to mean that she was not white but black. But Washington said he did not mean this, that he was talking about her complexion, not her race. As Florence Burns was very pale, Backus milked this for all it was worth to destroy Washington’s identification. The most likely answer is that, in the dim gaslight of the hotel, the woman he saw did indeed appear to have a darker complexion, as well as darker hair, than Washington at first thought. He had not seen her without her wide black picture hat until he went to the police station the following day to identify her.17

Washington stood his ground and never wavered from his identification of Florence Burns as the young woman with Walter Brooks. He even described what she was wearing that night, which matched what Harry Cohen said she had worn to the Brooks and Wells office that day. Nevertheless, this identification was undone, not just by the confusing “not a clear white woman” statement but by two separate lineup incidents at the police station that were out of his control. In the first, Washington had been told to poke his head into the room where Florence was being interrogated. His immediate recognition of her was discounted because she was the only woman there. In the second instance, Florence was put with two other women—both older, both shorter, both stouter, neither looking anything like her—and this invalid lineup also negated Washington’s picking her out as the woman he had seen.18

George Washington’s testimony was critical for the prosecution, as it put Florence Burns—or someone who looked very much like her—at the Glen Island with the victim. It is likely that if only one error had been eliminated—the “not a clear white woman” or the invalid lineups—the prosecution would have prevailed. But Judge Mayer thought the combination was enough to negate Washington’s identification testimony, and so he refused to consider it.19

JOHN EARL

The other Glen Island employee who might have put Florence at the scene was the night clerk, John Earl. He was the one who had signed in the three couples and was on duty at the time that Brooks’s companion would have left the hotel. Newspapers back then pulled no punches in their descriptions of people, so Earl was described as “not as astute as the Negro bell boy” and with a face “that does not display a sharp intellect.”20

Although Earl was all over the board with the time line, there were three items that locked him in: the victim’s 9:00 signing of the register, the 10:30 order of the lemon soda, and another couple’s signing in at 10:50. Earl claimed that the woman would have had to pass by his desk in order to leave the hotel and that he did not see her. He could not have identified her in any case, as all three women who came in at 9:00 stayed in a parlor and did not approach the desk while the men signed in.21

The woman must have left sometime between 10:35 (assuming five minutes for the lemon soda to be brought to her, the last reliable sighting being by George Washington) and 10:50 (when Earl was at the desk signing in the fourth couple). But she may have had a wider window of opportunity when it is recalled that John Earl, when it came to Glen Island Hotel activities, deliberately overlooked any untoward occurrences. Suppose he had seen a woman leave. He would not have known who she was, but in 1902, an unescorted woman leaving a hotel would have been noteworthy, and Earl would have been required to ask if she needed assistance had the Glen Island been other than a “Raines Law” hotel.

Because the Glen Island “asked no questions,” however, John Earl would not have done so. Probably there were prostitutes who frequented the hotel as well. After the murder, when he was being questioned about a solitary woman leaving the hotel, he may even have remembered that there was one, but if he admitted it, it would not reflect well on the Glen Island Hotel and could have cost him his job. He did admit that he might have turned his chair around for a better light while he read the newspaper, so that his back was to anyone leaving the hotel at that time. At any rate, Earl stuck to his story that he could not identify the woman with Walter Brooks, and this statement was undoubtedly true.

THE BRIGHTON BEACH “L”

But all was not lost in placing Florence near the Glen Island during the critical time frame. She had an admirer—nineteen-year-old Arthur Cleveland Wible,22 a conductor on the Brighton Beach division of the Kings County Elevated Railway. Florence Burns was a frequent rider on the Brighton Beach line since his hiring in May 1901, and Arthur and his fellow conductors always noticed her and the other pretty girls who rode with them. “She is the prettiest girl out there,” said one of the conductors.23 For the late-night trains, which ran only every half hour, the railway removed all but two of the cars that were necessary for the workday, so Wible easily noticed Florence on the shortened 11:15 train from the Brooklyn Bridge terminus. She was sitting three or four seats in back of the front door of the rear (second) car. He noticed her before she got on, and he nodded to her when she got off at her usual stop at Beverley Road, just a few minutes’ walk from her home. In court, when Wible took the stand, Florence gave a reaction that indicated familiarity with him and looked somewhat disconcerted.24

Thomas Smith, proprietor of a newsstand at the Brooklyn Bridge terminus, corroborated the testimony of Arthur Wible. Smith, who knew Florence by sight and by name, was just closing up his stand when she came across the bridge and got on the 11:15 train. These sightings contradicted Florence’s claim that she was home by 7:00 that Friday night.25

The Glen Island Hotel, today the site of the World Trade Center Memorial for the victims of the attack on September 11, 2001, was approximately half a mile from the Brooklyn Bridge. Even today, pedestrians can use the bridge walkway to go from Manhattan to Brooklyn, and back in Florence’s day, it was the only way to go from one side to the other unless one took a shuttle trolley or had an automobile. Eventually, the trains went all the way through, but that was still a few years away in 1902. How might Florence have crossed the bridge? The newspapers report that it would have taken her ten minutes to walk from the Glen Island to the Manhattan side of the bridge. From there, she must have taken a shuttle to the Brooklyn side, which was a mile away (and would have taken a brisk walker fifteen to eighteen minutes), as she got to the 11:15 train a little after 11:00. Flo’s parents had been to the theater in Manhattan that night and in all probability were on the 10:45 train. What an awkward encounter if they had been on the same train!

Arthur C. Wible, the young street car conductor (New York World)

Foster Backus, of course, maintained that Florence was not on the train. He produced Peter Bielman, a clerk in the Brooklyn surrogate’s office, who claimed he had been on that same 11:15 train and sitting in the car where Flo was supposed to be, and that she was not there. In fact, there was a “spoony” couple sitting in the exact seat where Wible said Florence was, and their public displays of affection were embarrassing to the other riders, so this incident stuck in his mind. These young people got off at Beverley Road. Bielman even provided Backus with the names of some of the other passengers on that train. Investigation must have discovered that Bielman was mistaken as to the day, however, as he did not testify under oath, and neither he nor those other passengers were heard from after that.26

THE TWO COUPLES AT THE GLEN ISLAND

As the hearing proceeded, the police were desperately trying to find two things: the pistol that was used to kill Walter Brooks and the two couples who signed in at the Glen Island Hotel around the same time as Brooks and his companion. Since the other two women spent time in the parlor with “J. Wilson’s wife,” the prosecution assumed they would have noticed what she was wearing. Apparently, they would rather have heard this from white women than from a black man.

Needless to say, the other two couples had no intention of exposing themselves to notoriety, as it was obvious what they were doing in that hotel, which was considered scandalous back then even if they were not cheating on spouses. They must have told other people, though, because eventually they were discovered. The women were sisters living in New Jersey, one unmarried and the other married with two children. Of the two men, one (unmarried) also lived in New Jersey and was in the brokerage business with the second man, who was married. Although no names were printed in the newspapers, there was probably enough identifying information to get these people in trouble. They were not put on the stand (one of the women said she would rather go to jail than testify, as it would ruin her), but the women were able to describe the third “wife” in the parlor, and the description matched Florence Burns.27

The pistol, however, remained elusive, although even the storm drains were being searched for it.28

THE MEDICAL TESTIMONY

The three physicians who testified could agree on only one point: Walter Brooks was killed by the bullet in his head. Otherwise, they disagreed as to whether Brooks could have moved after being shot or had been paralyzed by the shot. Dr. Philip Johnson, who assisted at the autopsy, held that the victim had been paralyzed, while Dr. John Sweeney said he was not. Moreover, Sweeney had tickled the bottom of Brooks’s foot and claimed that he got a response, which would negate paralysis. There was also some confusion as to whether Brooks had changed his position over the course of the night, which would supposedly have been impossible if he had been paralyzed.29

Foster Backus grabbed onto Sweeney’s theory and hinted that Brooks had been shot between the doctor’s first and second visits—which would mess up the time line for Florence’s involvement, even if she had been in the room with him. But as this would posit yet another woman wishing Brooks harm, who managed to sneak into the room after the first hypothetical woman had left, it strained credulity and so was not vigorously pursued.

Dr. John Vincent Sweeney, the on-call physician for the Glen Island Hotel, was born in New York City in 1858, the son of Irish-born immigrants. He graduated from the New York Homeopathic Medical College and his practice consisted primarily of obstetrics. Dr. Sweeney held some crackpot theories, among them a belief that when a community is not engaged in war for an entire generation, warlike tendencies become inert in unborn babies, which will then be awakened when war is actual or threatened… if their mothers are patriotic! “Virility begets virility,” he wrote. Sweeney himself never married.30

On his first day on the stand, Dr. Sweeney presented the time line of his three visits and denied having seen a comb in Room 12. But on the next day, he said that he had seen a comb and some hairpins in the room—just an ordinary comb, five inches long and made of celluloid, but missing some teeth. On cross-examination, he said he did not remember having been asked about it before and that possibly he had not understood the question. He was sure he could recognize the comb if he saw it again. After this, Foster Backus injected some humor into the proceedings by requesting that Assistant DA George Schurman produce the comb and hairpins because “combs and hairpins have been disappearing from my family at a great rate, and perhaps I’ll be able to trace them to room 12 in the hotel.” Everybody got a kick out of this, even Florence, who was usually stoically impassive in court.31

Schurman showed Dr. Sweeney the comb Thomas Brooks found in Room 12, but he did not recognize it. The one he saw in the hotel was lighter in color, had more teeth broken off in the middle, and was more perfect at the ends.32

The most puzzling medical testimony was that of the coroner, Albert T. Weston, who had performed the autopsy. The muzzle of the gun had been placed right against the victim’s skull at a point two inches behind the top of the right ear. From there, the bullet had progressed to a point that was over the left eye. This, of course, was not disputable. However, Weston was convinced that Walter Brooks had committed suicide! It was not physically impossible, of course, but it was such an awkward position that it’s hard to imagine that anyone seriously bent on killing himself would have attempted it.33

Furthermore, if Brooks had killed himself, where was the gun? Backus claimed that a hotel employee took it to prevent the other guests from being upset at the commission of a suicide, but the hotel countered with the argument that a suicide would be less upsetting to patrons than a murder. (In fact, there had been several suicides at the Glen Island over the years.)34 The most puzzling aspect of this is how Dr. Weston could have come to this conclusion. If he had a connection to Foster Backus or the Burns family, it was not revealed.35

Besides not having the temperament to commit suicide, Walter Brooks had made plans. He had arranged to meet with Harry Cohen that same night; he had promised Ruth Dunne that once he was free of Florence Burns, he would make another date with her; and not long before his death, he had ordered a new suit to be made for Easter (March 30, 1902) so that he could be in the Easter Parade.36

During the autopsy testimony, Florence fanned herself and yawned, giving the impression that she was completely uninterested in it.

MR. AND MRS. THOMAS W. BROOKS

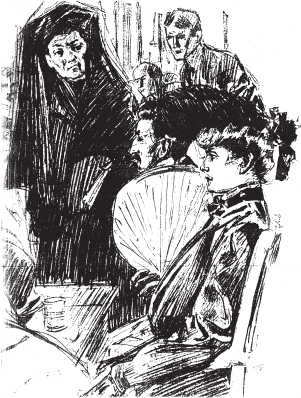

The most dramatic testimony was that of Walter’s parents, Thomas and Mary Brooks. That day, many “fashionably dressed women” came to court. In general, over the course of this hearing, women outnumbered men by approximately ten to one, but on this particular day, so many showed up that “there was no room for a man in court.” Instead of the young “belles,” however, this day’s audience was “like an old maids’ convention,” with row after row of older women garbed in funereal black, much to the disappointment of the young Brooklyn Eagle reporter.37

Another visitor was the famous artist Charles Dana Gibson, creator of the Gibson Girl, who had come to observe Florence Burns, possibly with an eye to sketching her. If he ever did so, it has not surfaced.38

Also attending the hearing was the eccentric, way-ahead-of-her-time Dr. Mary Edwards Walker, sixty-nine, who had been awarded the Medal of Honor (the only woman and one of only a handful of civilians ever to receive it) for her bravery in the Civil War as a doctor and as a prisoner of war. A staunch feminist and suffragist, Dr. Walker usually wore men’s clothing because women’s clothing was too restrictive and because the long skirts and dresses picked up and spread disease. She was correct on both counts. At the Burns hearing, Dr. Walker had a tendency to voice her approval or disapproval, sometimes even clapping her hands, and was invariably scolded by Judge Mayer, which stifled her not at all.39

As for Florence, she just kept on fanning, even when Mrs. Brooks stopped on her way to the stand and stared at her “with hatred and disgust.” This meeting was exactly what the many women in court that day had come to see, and they were not disappointed. It was a thirty-second stare down and caused Florence to blush.40

Walter’s mother’s emotional testimony consisted primarily of her many encounters with Florence during her three-week stay with them when Florence constantly threatened to kill Walter. As Mrs. Brooks recounted it, it seemed to happen every time they met, every single day.41

When Mrs. Brooks had been on the stand for approximately half an hour, she was shown the watch found in the hotel room and identified it as her son’s. Holding Walter’s watch, which she tenderly kissed and held close to her face, caused such emotion in her that she collapsed from a seizure-like fit and had to be carried out of the courtroom by four attendants—right past Florence’s end of the defense table. Mrs. Brooks’s garments even brushed her slightly. Yet Flo kept on fanning and gave no reaction whatsoever, not even looking at the unconscious woman.

Mrs. Brooks was able to continue her testimony forty-five minutes later, when she gave the time line for Florence’s involvement with the Brooks family and identified the comb her husband found in the hotel room as one she had seen in Florence’s room. On cross-examination, Backus pulled a trick on her and removed the evidence tag from the comb, then asked her to identify it. She said she could not, that it did not resemble the combs she knew that Florence used, and she had never seen this particular comb. This, of course, was like the “one-man lineup,” in that the identification tag tipped her off to the comb found in the hotel room where her son had been shot. But she couldn’t really identify it.

Mrs. Brooks was also confused by Backus’s constant changing of combs, then removing them from her sight and asking her to identify the comb she had just held, without looking at it. At one point, pressed to answer whether she had ever seen a particular comb, she said, “I am getting dazed and tired out.” Backus thought she was shamming to avoid answering and asked that the incident be noted in the record.

Backus had a dilemma in cross-examining Mary Brooks. She was a grieving mother who received much sympathy for the loss of her son, so if he came on too strong in his questioning, he would be viewed as a heartless monster and, by extension, Florence would as well. Yet, he had an obligation to defend his client, and he knew there were some holes in this witness’s testimony. Although there was no jury to consider at the moment, a potential jury pool was following the hearing every day in the newspapers. So, instead of attacking her, he let her own answers illustrate the essential contradiction in her testimony—that despite the many threats Florence Burns uttered, nobody but Mrs. Brooks ever heard them, and the Brookses allowed her to continue to live in their home for three weeks:

FOSTER BACKUS: Did Florence ever make any threat she would shoot your son before she was sick in your house?

MARY BROOKS: Yes, sir.

FB: When?

MB: About the third time I saw her.

FB: How many times and in how many conversations did Florence Burns tell you she would kill Walter?

MB: The last week she was in my house she told me on Monday, Tuesday, and Thursday.

FB: She told you before that also?

FB: Did she tell you every time she saw you?

MB: No, sir.

FB: Did she tell you pretty nearly every time she saw you?

MB: No, not as often as that.

FB: Did she ever tell you that in the presence of anybody else?

MB: No, sir.

FB: She and Walter kept going together after she had told you that, didn’t they?

MB: Yes, sir.

Asked if anyone else was present when Florence told her about trying to get her father’s pistol, Mary Brooks admitted that there was not:

FB: What did you say to her [about getting her father’s revolver]?

MB: I didn’t say a word.

FB: Did she stay there and talk to you after that?

MB: Yes.

FB: Now how many times that week did she tell you she’d kill Walter?

MB: Every day that she was in my home that week. She ended every conversation by saying: “I will kill Walter unless he marries me.”

Thomas Brooks, who had picked up the comb in the hotel room, had never seen, or at least had not paid attention to, any combs that Florence Burns had worn, nor had he seen any in their home. He thought the comb in the hotel room might have been a clue, so he took it and gave it to a policeman, who later came to the Brooks home. When he described getting to the hotel, where his son lay dying, he broke down briefly before he could continue. While spectators were moved by Mrs. Brooks’s emotional collapse, they were far more affected by her husband’s sobbing when he recounted the scene.42

THE “FAT BABY” FROM BAYONNE

If you were living in the Victorian or Gilded Ages and were unlucky enough to find yourself part of a high-profile murder case, you would hope to be entirely free of any physical flaws or personality quirks because these would be described in the newspapers as part of the entertainment for their readership. This is what happened to nineteen-year-old William Armit Eyre of Bayonne, New Jersey, “a very fat young man,” standing six-feet-two and weighing approximately 250 pounds, which makes him obese according to today’s body mass index scale. After testifying, he was known to all as “Fatty” Eyre, and then as “that fat baby” in a scathing summation by Foster Backus.43

Eyre claimed that he, Walter Brooks, and Florence Burns had gone to the theater in September 1901. He was already acquainted with Brooks, but it was his first meeting with Florence. In the streetcar on their way to Weber & Fields’ Music Hall to see the play Hodge Podge, Walter and Flo quarreled constantly. Unwisely, Walter interrupted the quarrel to point out a pretty girl to Eyre: “Billy, she’s a beauty!” Eyre replied, “Yes, she’s a peach.” Florence’s response was to look at Brooks angrily, “as if she was going to eat him up right there in the car,” and told him, “If you say that again, I’ll crack your nut.” In the play, an actress told her boyfriend she would kill him if he ever left her, and Florence told Walter she would do the same.

Eyre’s connection to Walter Brooks was through the grocery business. “What kind of goods?” Backus asked him. “Everything from sauerkraut up,” Eyre told him, an answer that, for some reason, caused much laughter in the audience.44

“Fatty” Eyre supposedly told acquaintances over in Bayonne, New Jersey, that he had fabricated the whole story—that he had not been on the streetcar with Walter and Flo. Rather, that it was Walter who told him that Flo had threatened to kill him. When challenged about the discrepancy, Eyre insisted that he had heard her say this herself and that he never told anyone otherwise.45

However, there was a better than even chance that he had lied about some or all of this. He also claimed to have gone to Lehigh University and played left guard on their varsity football team in 1899 and 1900. Like Theodore Burris’s false claim about having attended Cornell and playing football there, Eyre neither attended Lehigh nor played on its football team.46

Eyre had a money stunt that he pulled in bars, whereby he would drink a glass of whiskey, then offer to eat the glass for five dollars. Invariably, someone would take him up on it, whereupon Eyre would break the glass, then chew it up and swallow it. A surgeon who took out Eyre’s appendix noticed there were shards of glass in his intestines, along with a quantity of pus. Although Eyre denied that he swallowed glass on purpose (“How I ever swallowed it, I don’t know, nor do I have any idea”), his friends verified the whiskey-glass story, and a witness at the operation said that Eyre had notified the surgeon in advance that there would be glass in his intestines.47

So, “Fatty” Eyre was quite capable of lying and may have done so in the Brooks-Burns hearing, possibly—as do so many in high-profile cases—to gain a measure of fame by inserting himself into the story. In his defense, however, his quote of Florence on the streetcar sounds very much like her, so if he was not in her presence, Brooks probably told him this.

THAT COMB AGAIN

Today, with all the advances in forensic DNA technology, we would need only a strand of hair from a comb or a brush used by a victim or a suspect. Unfortunately for the prosecution in the Brooks-Burns case, unless there were some distinguishing characteristics in Florence’s combs that could tie her to the one found in Room 12 at the Glen Island, none of the comb testimony was probative. And it was all so tenuous. Thomas Brooks had picked it up from the dresser next to the bed, thereby tainting this evidence, from today’s standpoint. It could be argued that he had taken one of Florence’s combs left behind at his home and claimed he found it in Room 12, but he was oblivious to what kinds of combs Florence had and saw none when she was living in his home for three weeks. Mary Brooks claimed to have identified the Room 12 comb as one belonging to Florence, but it became very obvious that she wished it to be so rather than knew it to be so. Dr. Sweeney at first said he did not notice any combs in Room 12, then later said he had, but that it didn’t look like the one placed in evidence.

In 1902, women’s combs were so ubiquitous and common as to be indistinguishable unless they were made of very expensive material or had unusual designs. But the everyday combs worn by most middle-class women were plain celluloid ones, the same material that made up men’s detachable collars and cuffs. Unless the Room 12 comb could be definitively tied to Florence, all the testimony in the world about her combs would be useless.

That did not prevent the prosecution from trying yet again, this time with the young chambermaid in Mrs. Hitchcock’s boardinghouse, where Florence had lived for a month. Julia McCarthy, always described as “a mulatto” or “a Negress,” had found a comb underneath the dresser in the room occupied by Florence Burns. She put it on the dresser, where it stayed for three days, so she got a good look at it during that time, and she also remembered it because it was so dilapidated, “a horrible sort of comb to be in a lady’s room.” McCarthy was adamant that it was the same comb as the one placed into evidence, and she could not be shaken by Backus’s cross-examination, drawing great praise from the Brooklyn Eagle reporter for her firm and straightforward testimony. While Julia McCarthy was on the stand, Florence Burns was noticeably nervous and seemed to be embarrassed, turning red and biting her lip.48

THE DETECTIVES

The three detectives involved with the arrest and questioning of Florence Burns—Colby, Riordan, and Parker—repeated what she had said to them at her home and at the police station on February 15. Her admissions were damning and amounted to a confession, so Backus fought hard to keep them out. Detective Sergeant Parker, “a fat fellow with a mustache—a typical policeman,” got so tangled up in his cross-examination that the audience roared with laughter until Judge Mayer threatened to empty the courtroom.49

Backus focused on Parker’s refusal to allow Fred Burns to see his daughter and also on whether Florence had been advised of her right to keep silent:

BACKUS: Did you see Mr. Burns … [at] the Church street station?

PARKER: Yes, as I was coming out of the captain’s room where she was, and I met him at the door. He said he wanted to go in and see his daughter. I told him that it was impossible then and asked him why he wanted to see her. He said he wanted to tell her not to say anything. I told him she had already been told that.

BACKUS: Now, had you heard any one tell her not to say anything?

PARKER: No.

BACKUS: Then why did you tell him that?

PARKER: You misconstrued my words. I said she had been told she was entitled to her rights.

[It was in here that Parker got confused and made “ridiculous statements,” not transcribed in the newspapers, to the great amusement of the spectators.]

BACKUS: Why did you tell Mr. Burns he couldn’t see his daughter?

PARKER: Why, because she was charged with a felony and no one could see her until she was turned over.

BACKUS: Turned over to whom, for God’s sake?

PARKER: I don’t know.50

After the testimony of the three detectives, Judge Mayer made it clear that he did not trust their evidence and had grave doubts about its admissibility because Florence had not properly been apprised of her rights before she was questioned in her home or at the station. Colby and Parker were in plain clothes and did not inform her that they were detectives. Nor was she told why she was being arrested—just that it was a felony, not that it was a murder. She had not been taken directly to a magistrate before she was questioned. Moreover, he leaned toward Backus’s assertion of Florence’s having been given the “third degree,” although she had not been threatened and had been questioned for, at the most, only two hours, while many of the witnesses were routinely questioned for three. Mayer asked the attorneys to come back the next day prepared to argue these points as he was inclined to throw out Florence’s statements. If he were to do so, the prosecution would have virtually nothing that would allow them to go ahead with a trial, although the district attorney would still be free to get there by way of a grand jury indictment, and there was still an inquest hearing in the offing. It must have looked very bleak to Assistant District Attorney Schurman at the end of court that day.51

RUTH DUNNE

Like Florence Burns, seventeen-year-old Ruth Maria Dunne was pretty, blonde, and in a constant battle with her parents, Thomas and Bridget, both of whom were born in New York to Irish immigrants. Ruth, born in 1884, was the oldest of four children (a fifth had died before 1900) and three years younger than Walter Brooks.52 When her parents were not around, she told reporters that she was engaged to Walter, but when they were on the scene, she said she saw him only a couple of times. Her mother was convinced, or claimed she was, that Ruth barely knew him and was definitely not engaged to him. (Did Ruth think her parents did not read the newspapers?)53

Ruth probably exaggerated her relationship to Walter as they had been dating for only a month, so were probably not engaged. And Walter, already averse to such a commitment, would not have been likely to take it on when he was still somewhat tied to Florence—especially if there might have been a baby involved. But under oath, Ruth testified to having been with him nearly every day for the week before he died. And he was supposed to meet her the night of February 14 but broke it off so he could give Florence a “blowout” to send her off to Detroit and be rid of her at last. If these somewhat checkable assertions were true, then they were definitely spending a lot of time together.

Ruth preened and chatted with reporters and was dramatically hysterical during some of the testimony to the sarcastic amusement of Florence Burns, who recognized it for what it was. But when Ruth got on the stand, she was so timid and nervous that she could barely be heard in the courtroom.54

Ruth’s testimony was very precise as to time and place, so it was probably true, but none of it tied Florence Burns to the Glen Island Hotel, although her presence in Walter’s life could provide further motive on Florence’s part. Ruth had never heard Florence threaten Walter and had only heard of her temper tantrums from Walter himself. It’s not even clear that she and Florence were more than marginally acquainted. Still, they practiced the same lifestyle: staying out all night, going to cheap theaters, and hanging out at Coney Island and Bader’s with boys of the Bedford Gang.

Although the prosecution claimed that it had much stronger evidence that it did not want to bring out for the defense to see, it had a hollow ring—like that of Foster Backus’s mythical alibi claims. And, if Judge Mayer did not allow Florence’s admissions into evidence, the district attorney did not have much of a case at all.