11

THE INQUEST

Another unusual aspect of the Brooks-Burns case was the delay in holding the inquest until after the special hearing. The normal procedure at that time was for the coroner to summon a jury immediately, often from the crowd of onlookers at the crime scene, with the examination of witnesses and evidence to take place on the premises, even in the victim’s own house.

The function of the inquest was to determine the legal cause (referred to as “manner”) of death, whether by accident, homicide, suicide, or the delightfully quaint “misadventure” (i.e., through the victim’s own carelessness, often by doing something he or she should not). In the case of a verdict of homicide, the jury was to recommend either the name of the most likely suspect or conclude that it had been committed by “a person or persons unknown.” The standard, as at the preliminary hearing to determine probable cause, was the same as for civil cases: “more likely than not” or at least a 51 percent probability that the suspect named was guilty. The suspect was then bound over for trial, where the standard of proof would then rise to “beyond a reasonable doubt.”

The inquest jury, unlike that at a trial, was allowed to ask questions of the witnesses brought forth by the prosecution. There was no presentation by the defense, but Foster Backus asked for and received permission from the coroner to cross-examine the prosecution’s witnesses, which he did with a vigor that frequently had to be tamped down by the coroner.

New York City’s coroner in 1902 was Nicholas T. Brown, a fifty-two-year-old former alderman who, in campaigning for election as coroner, got himself arrested for being drunk and disorderly. As alderman, he had been accused of corruption as the henchman of the notoriously corrupt police justice Patrick Divver in Tammany Hall and, as a result, some important groups did not endorse him for coroner. Nonetheless, he was elected, and with quite a large margin. In 1918, New York City would change over from the system of coroner to that of chief medical examiner.1

The district attorney’s office was anxious to get Florence Burns back under its jurisdiction by serving a subpoena on her to appear as a witness so that the jurors could observe her demeanor for themselves. But that subpoena could not be served outside the state of New York, and, in any case, she could not be forced to testify against herself. Backus would not reveal where she was or even which state she was in, but he promised to produce her if a valid arrest warrant were to result from the inquest.2

There was a supposed sighting of Florence at the River Styx resort area of Lake Hopatcong in New Jersey, and shadows of a woman were seen through the curtains on the top floor of Oscar Von derBosch’s summer home in Cortlandt, New York, which was occupied by the family of Von derBosch’s sister during the other seasons. But nobody knew for sure where Florence was.3

Notwithstanding the absence of the “main attraction” from the coroner’s inquest, the courtroom was crowded with spectators throughout the eight days it lasted. Many of the witnesses who had testified at Judge Mayer’s hearing came to repeat their testimony, or a current version of it, except for William “Fatty” Eyre and Julia McCarthy. Eyre refused to submit himself to ridicule again, and McCarthy could not be located, having moved out of state for another job. Their testimony was read into the record.4

Ruth Dunne was there, as were Walter Brooks’s parents, the bellboy George Washington (“Yes, I could identify her among a hundred women”),5 the physicians (Dr. Weston, Dr. Johnson, and Dr. Sweeney), the streetcar conductor Arthur Wible, and Walter’s business partner Harry Cohen. Some new witnesses added spice to the proceedings, the most notable of whom were members of the Bedford Avenue Gang.

BAD BOYS

William Maxwell “Max” Finck, twenty-four, and Joseph Wilson, twenty-three, were currently serving forgery sentences in the Elmira Reformatory, now the Elmira Correctional Facility, in upstate New York. A fellow forger, George F. Jackson, was not brought down for the inquest as he had no probative testimony to offer. Max Finck belonged to a socially prominent family, but, like Theodore Burris and Harry Casey, he could not stay out of trouble. When he was seventeen, he felt he was not making enough money working as a typist for his uncle, so he ran away to become a traveling salesman. (Given his later history, he most likely stole the items he was selling.) Two weeks into his new life, Max tried to jump a freight train carrying coal near Ansonia, Pennsylvania, and missed. The train ran over his right leg and severed it above the knee. From then on, he had a wooden leg.6

In 1901, Finck and Jackson had made up fake advertising contracts, passed them off on Finck’s employer, then went to Richmond, Virginia, with the money they got for those. In Richmond, the boys presented a bad check for five dollars, and moved on to Washington, DC, where they presented another one for fifty dollars. In Brooklyn and Manhattan, they solicited ads for nonexistent college football and track programs.7

In September 1901, Max Finck and George Jackson picked up a couple of girls at the popular Brooklyn resort, Bergen Beach, and took them to a nearby dance at the Prospect Park Hotel. The four of them were drinking quite a bit and, as Jackson said later, were “ossified” to the point of not knowing, or claiming not to know, what was going on. They roused a minister from his bed and got him to marry George and one of the girls, Dolly Nicholson. Then the boys disappeared.

The next day, Dolly declared she had been married, but she had been so drunk she was confused as to which one was her husband. She thought it was the one with the wooden leg (Finck), but it turned out to be Jackson, who had given the name of a relative in Pennsylvania instead of his own. When reporters tracked down the families, Max’s mother was furious—her son was not married to Dolly Nicholson, despite what the girl said, and possibly some other young man was using Max’s name. When George Jackson got back to town, he claimed to know nothing of his having been married. Yet, certificate No. 5919 shows that he was!8

When Finck and Wilson were arrested, Finck agreed to turn state’s evidence against several members of the forgery ring in exchange for a suspended sentence. But the judge, who had discovered some of Max’s other antics, refused to uphold the district attorney’s deal and sent him to Elmira.9

The reason Max Finck had been brought to the inquest was to testify to an incident from February 1901 at the Palace Hotel in New York. This was before Florence had met Walter Brooks and, at the time, was dating “Handsome Ed” Watson. Florence was wearing a muff, from which she had taken a .32-caliber pistol and threatened to shoot Watson. Max Finck managed to disarm her, with difficulty, removed the bullets, and threw them away. He did not remember what the pistol looked like, only that it had a light-colored handle. Florence told him the pistol used to belong to her father. He never heard her threaten Walter Brooks.10

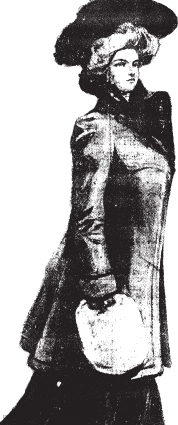

Joe Wilson was also there to testify to Florence’s possession of a pistol. Wilson had dated her after Ed Watson, and he knew she kept it in her muff because he had seen it. He asked her why she carried a pistol and she told him that she lived in a “lonely part of Flatbush and might need it for self-protection.” Like Finck, Wilson could not describe it, other than that it had a light-colored handle. He knew that Florence and her mother were both very skilled with firearms and had won prizes at shooting contests, which was corroborated by Harry Cohen. Wilson was a good friend of Walter Brooks and had known the family for about six years. When Wilson was on trial for forgery, he was defended by Mr. Brooks’s lawyer, and when Wilson and Finck were in the Tombs, Walter visited them there. Joe had met Florence at the Haymarket Dance Hall in Manhattan and told an inquiring juror that, yes, this was before he had been introduced to her: two major faux pas for that era.11

Florence Burns with muff; friends testified that she carried a pistol in it (New York World)

The Haymarket Dance Hall, at Sixth Avenue and West 30th Street, and located in the Tenderloin district, known as “Satan’s Circus,” was notorious for its bawdiness, despite its respectable outward appearance and its restriction against too-close dancing. Prostitutes frequented the Haymarket, as did shopgirls and those of the higher classes who were “slumming,” like Florence and her cohorts. Authors Greg Young and Tom Meyers call it “a veritable shopping mall for sin” with “curtained-off rooms in the balcony and upper floors.” The colorful eroticism of the Haymarket is depicted in a famous painting by John Sloan.12

As for Wilson not having been introduced to Florence before speaking to her, that was a tradition that—thanks to informal places like Coney Island—was fading out with the younger generation. For older folks like the juror who asked about it and the parents of these young people, it was proof that a girl was “fast” and had compromised her virtue by allowing a young man to speak to her without a proper introduction by a mutual acquaintance—and at the Haymarket, no less.

Another bonus for the inquest attendees was the presence of Edward Cole Watson, who had not been at the Mayer hearing. “Handsome Ed” corroborated Max Finck’s account of the Palace Hotel incident where Florence threatened him with a pistol. Neither of these boys gave the exact day in February for this, but February 15, 1901—exactly one year before the death of Walter Brooks—was the date Florence gave to Mrs. Birdsall as to when she “went wrong” with Ed Watson.13

MRS. BROOKS CHANGES HER STORY

Undoubtedly realizing that her possibly exaggerated story of Florence’s constant threats against her son was not rational in light of the Brookses’ three-week tolerance of her presence in their home, even after these threats, Mrs. Brooks now testified that they had thrown Flo out of their house after the first threat. Asked about the discrepancy with her previous testimony in front of Judge Mayer, she said she could not remember that. Since Judge Mayer based part of his decision to dismiss the case against Florence Burns on this testimony, it was obvious that Mrs. Brooks was hoping to avoid another dismissal.

However, she did reveal something interesting that had not come up before, which was the supposed statement made by a physician called in to attend to Florence when she was sick: that the young woman was faking illness and should be sent away from their home immediately. Given that Mrs. Brooks had already been caught in a lie, had never brought this up before, and a doctor had already diagnosed Flo’s illness as real, this was highly suspect. It was also hearsay, which would not have been allowed in a trial. If it were true, why didn’t the Brookses get a written statement from the doctor who said this, or even bring him to the inquest hearing?14

When Thomas Brooks was on the stand, a juror asked him about the Brookses’ invitation to Florence to stay in their home, their tending to her illness, and their allowing her to stay for three weeks. In a subtle allusion to the application of the Unwritten Law, the juror wanted to know if it was because they felt that Florence “had a moral claim on them.” Mr. Brooks denied any such claim. But the fact that he was questioned so closely in both hearings regarding the nature of Flo’s illness indicates that there was always that suspicion of a pregnancy, which would have been a very large moral claim indeed.15

As she sat in the courtroom with her husband day after day, Mrs. Brooks frequently burst out crying or shouted disapproval. One time, she stood up and insisted that Walter had been drugged with chloral when he was drinking with friends at Bader’s and that they never found him until the next morning. There is no doubt that Mrs. Brooks believed (or chose to believe) this outrageous story, but what was really odd is that Walter’s second partner—Thomas C. “T. C.” Wells—proclaimed from his courtroom seat that he remembered that very time as well.16 It’s not likely that Brooks was drugged because what would have been the point, other than maybe as a bad practical joke? Was he left all night at Bader’s? Maybe T. C. Wells did not want this distraught mother to doubt the goodness of her son, who had stayed overnight at the roadhouse and needed an excuse for not going home.

THE TIMING EXPERIMENT

The detectives from the various police stations repeated their observations and Florence’s incriminating statements, hoping that this time these statements would be allowed into evidence. There was a new aspect in the testimony of a detective who had done timing experiments to test Flo’s claims. It took him nineteen minutes to get from the Glen Island Hotel to the Brooklyn Bridge at a “leisurely pace.” “Leisurely,” indeed: it was only half a mile, and Florence’s pace would have been brisk to distance herself from the hotel and get to the streetcar on time. His next experiment was more to the point: it took him forty-one minutes to get from the Brooks and Wells office at 17 Jay Street in Manhattan to the Beverley streetcar station in Brooklyn (about a two-minute walk from her home). Florence claimed she had left the office at 6:30, although others said it was more like 6:45 when she left with Walter. With either time, however, she would not have made it to her home by 7:00, which is the time she said she arrived there.17

THE REST

Except for the addition of a young man who claimed he had seen Florence’s combs in his mother’s boardinghouse (but could not conclusively connect them with the one found in the hotel),18 the other witnesses were all carried over from the preliminary hearing.

The “fair and pretty” Ruth Dunne recounted her last days with Walter Brooks and mightily disappointed the spectators by not being allowed to read the letters she identified as having been exchanged between them. Ruth was there every day, having been hired by one of the “yellow” papers, probably the World or the Herald, to report on the inquest. Walter’s partner Harry Cohen said that Florence had a muff with her when she visited their office on February 14, important testimony after what Max Finck and Joe Wilson said about Florence keeping a pistol there.19

THE VERDICT

In his charge to the jury, which was heavily prosecution-oriented, Coroner Brown emphasized the testimony of conductor Arthur Wible and the detectives’ report of Mrs. Burns that indicated she and her husband already knew about the shooting. Throughout this charge, the jury acted bored and inattentive. The reason for this, as a juror later gleefully confided to a reporter, was that they had already made up their minds.20

The verdict of “murder by a person or persons unknown” took exactly fifty minutes and “no single juror had favored a verdict placing the responsibility of Brooks’ death on Miss Burns.”21 With such unanimity, it is not hard to imagine the jurors all taking out cigars or pipes or cigarettes to enjoy a smoke and give the illusion of an actual deliberation. The fifty minutes occurred over a lunch hour, so maybe they also had something to eat.

It’s not hard to read beneath the reasoning (not wanting to put the responsibility for Walter’s death onto Florence) and see the workings of the Unwritten Law—not that she didn’t do it, but that they did not want to hold her responsible.

Mrs. Brooks had stayed home for the verdict they must have known was coming. Her husband was quite upset about it: “This verdict is, indeed, a blow to me.” At the opposite side of the spectrum was Florence’s attorney, Foster Backus, who had surely earned every penny of the $6,000 her uncle paid him. With obvious relief that the three-month ordeal was over, he was “completely overcome and sobbing like a child.”22

Now having failed twice in his attempt to try Florence Burns for the murder of Walter Brooks, District Attorney Jerome decided to hold off on going to the grand jury. But he and everyone else knew that the Brooks-Burns case was over. The Burnses could now return to their home, free of subpoena servers. And Florence could attempt to get back her life and her reputation.

HERE’S WHAT MIGHT HAVE HAPPENED

Florence Burns was desperate. Somehow, she needed to convince Walter Brooks to marry her so she could redeem herself in the eyes of her parents. She had always had sexual power over him, and she was banking on that if she could only get him to see her. She made up a story about moving to Detroit the next day and waited for him to show up at his office. With the Detroit story, however, Walter—rather than fearful of losing her—could see light at the end of the tunnel of their relationship and agreed to go out with her “one more time.” He even generously offered to give her $60 for her trip. It is remotely possible that Florence presented the Detroit trip as a trip to an abortionist, as she did not seem to have any connections in that city. This would also explain the money Walter gave her “for expenses.”

They left the office around 6:45 or 7:00 and went to dinner, probably at Walter’s favorite place, the Cosmopolitan on Chambers Street. Florence suggested that they find a Raines Law hotel where they would not be questioned about luggage and have one final “fling.” Walter was feeling expansive because, after that, he would be free.

Florence must have thought that sex could persuade Walter to change his mind and agree to marry her. When she could not get him to budge, she might have been so filled with rage that she decided she would get even by shooting him. She waited until he was asleep (or maybe chloral was used, as Dr. Sweeney said he had smelled it), put the pistol right up against his head to minimize the sound and to make sure of a direct hit, and pulled the trigger. When she called for the lemon soda, she had no doubt already shot him and probably assumed he was dead. Then she got into her clothes, blew out the gaslight on the radiator without turning off the gas, and left.

The mystery here is why, if Florence were angry at Walter for not changing his mind, she did not confront him with the pistol so she could get some satisfaction by letting him know why he was going to die. Instead, she opted for drugging him and shooting him as he lay unconscious. Perhaps part of the answer lies in the cases of Nancy Bachus and Francine Hughes, who were a good deal smaller and weaker than their husbands. Walter was over six feet tall with an athletic build and would have put up noisy resistance, and Florence would have had to stifle the sound of the pistol to prevent attracting attention so she could slip out quietly.

Was John Earl at his desk when Florence walked by? If so, was he busy checking in the couple at 10:50 and unable to pay attention? Or was his back turned to her so he had better light for reading his newspaper? Or did he notice her and say nothing because of the Glen Island Hotel’s policy of employees keeping their mouths shut?

Florence would have wanted to dispose of the pistol as soon as possible in case the shooting was discovered and someone came running after her. We know she didn’t keep it because her first question was whether they had found it. Throwing it into the East River would have been her best option, and maybe she could have accomplished this before getting on the trolley that took her to the Brooklyn side of the bridge.

When Florence got home, her parents were already there, having arrived about a half hour earlier from their theater date in Manhattan. It was at this point that she told them whatever story she had concocted, probably the murder-suicide one. Fred ran out, either then or early the next morning, to enlist his friend Foster Backus, who agreed to take on the case if Florence were arrested. Before leaving for his office the next morning, Fred Burns enjoined his family to say nothing to anyone who might ask about the shooting of Walter Brooks.

The most damaging evidence against Florence Burns was that she had been with Walter Brooks earlier that night; she knew exactly how much money he had after he paid for dinner and the two-dollar hotel room; she had obviously told her parents he had been shot; and despite a three-month high-profile case covered by every newspaper in the country, not one person came forward to give her a solid alibi. Not even her own family could do so.

WAS THERE A BABY?

Nothing that is known of this case goes toward proving that Florence Burns was not pregnant when she killed Walter Brooks, and there is much to indicate that she was. However, without an actual baby or a statement from her or someone with access to the truth, it cannot be definitively proved. Here are seven indicators that make it more likely than not that she was:

1. Florence was sexually active: We know this not only from the extant rumors about all the Bedford Gang boys, not just Walter Brooks, being intimate with her but from her own statement to Mrs. Birdsall that she “went wrong” with Ed Watson in 1901.

2. Flo’s parents: The Burnses’ extreme reaction to their daughter’s relations with Walter Brooks—to the point of throwing her out of the house and refusing readmittance unless she married Walter—indicates there was a pregnancy. Fred Burns said that Mr. Brooks was a “criminal” and should be in jail for objecting to the marriage. He told Walter that if he did not marry Florence, he (Fred) would go to hell. Since the Burnses did not exhibit this same reaction to Florence’s relationship with Ed Watson, even though they also kicked her out of the house for that, there must have been more at stake.

3. Flo’s admissions to Mabel Cooper: In September 1901, Florence confided to her friend Mabel Cooper, as well as Mabel’s mother, that she was “in serious trouble” and that Walter Brooks was to blame. If she could not “regain her health,” she told them, she would take her revenge on Brooks. (Readers of a certain age will be familiar with the term in trouble with regard to an unwed young woman.)

4. Walter’s parents: The Brookses clearly did not like Florence Burns, and they particularly objected to their son marrying her. Yet, they consented to her extended stay in their home during her illness, whatever the cause, paid for a physician to attend her, and allowed this to go on for three weeks, despite Florence’s threats against their son. This seems unreasonable indeed unless they felt she had a “moral claim” on them because of a pregnancy for which their son was responsible.

5. The timing of Florence’s desperation: Florence seems to have stepped up her demands that Walter marry her. When he asked her where and how they would live, as he had no money, her response was, “But we must get married.” (Again, readers will recognize “they had to get married” as a code phrase used in past eras when there was a pregnancy involved.) And when did Florence’s desperation intensify? Right around the time when a pregnancy would be noticeable, in the fourth or fifth month.

6. Florence’s special treatment in the Tombs: Pregnant prisoners were given special exercise privileges, and these were extended to Florence. Unfortunately, by the time this became known, the Tombs Angel—who would have asked for it on Flo’s behalf—had died in the Park Avenue Hotel fire and could not be asked about it. The Tombs administration did not deny it, only stated that Florence was not given any privileges not extended to others. The rumors persisted in the press. “She is about to become a mother”23 was about the most straightforward assertion, but there were strong hints throughout. (It should be noted here that the word pregnant was rarely used in print at that time, even into the midcentury.) Foster Backus denied this and said that he was willing to leave Florence in jail for any length of time so they could see there was no baby,24 but it was an empty promise, and he made sure to remove her from sight as soon as the Mayer hearing was completed.

7. Florence’s extended absence: If there were a baby on the way—and we use Florence’s statement to Mabel Cooper in September as a benchmark—it would have been born in May or June 1902. Florence won her discharge on March 22 and the inquest hearing—with District Attorney Jerome’s decision not to proceed further—ended on May 19. Soon after that, Mr. and Mrs. Burns and their daughter Gladys moved back to their home. But Florence was not with them. Nor did she rejoin them until mid-July. This time span would allow for the birth of a baby in June and Florence’s recovery from that. Although today’s new mothers are up almost immediately after giving birth, this is a recent phenomenon. Up until the late twentieth century, mothers and their newborns stayed in the hospital for a week after the birth, followed by the mother’s bedrest at home for another week. In the middle of April, there was a brief comment by Foster Backus that, despite the rumors from an unknown source, Florence was not seriously ill.25 This was an odd report and the subject of her ostensible illness was never referred to again. Alone of all newspapers, the Columbia, South Carolina, State proclaimed that Florence had gone to Charleston to “make her future home.”26 There are several pronounced references to the physical intimacy between Florence and Walter, possibly insinuating that Florence was leaving to have a baby there. However, in her own article written for the Herald in November, she mentioned only the small towns of New York and New Jersey. But it gives her an excuse to have delayed her return to Brooklyn, so she may have made up the story about moving to Charleston.

So, there are many hints that Florence was indeed pregnant, and if she was, it makes a lot of her behavior, as well as that of Walter and the two sets of parents, more understandable. But what might have happened to the baby? It definitely did not go back home with Florence, so someone must have taken it. The most logical adoptive family would have been one related to Florence to avoid the possibility of the baby’s existence leaking out to the public. Yet, a search in the 1910 census of the known Burns/Von derBosch relatives did not reveal the presence of a child of the right age: seven or eight years old.

Florence Burns never addressed this issue, at least in a way that was made public. In the 1910 census, there is a question for married and widowed women to indicate how many children they have borne, and how many of those are still alive. At that time, Florence was married, so she would have been asked this question, but in the circumstances she found herself at the time, she was probably avoiding the census taker. Those circumstances will be the subject of the next chapters.