12

FLORENCE’S NEW LIFE

When Florence Burns finally rejoined her family at their home in July or August 1902, the reunion was unlikely to have been a joyful one. Her parents, particularly her mother, were mortified beyond belief by the court hearing and the attendant publicity. (Mrs. Burns constantly referred to the entire incident as “our trouble.”)1 Now that they had their daughter back, they had no intention of allowing her to parade herself before the neighbors or take up her former life with the Bedford Avenue Gang and her other friends.

Florence then sulked her way through the rest of the summer and the fall, constantly resentful of being a prisoner in her own home. She refused to do any housework, but this was nothing new: she had never done any, so Gladys pitched in instead. Oh, there were the (very) occasional visits to Bergen Beach on hot days, but she was always accompanied by an adult relative. She was not allowed to venture out of the house by herself. And she described her situation, past and present, in melodramatic terms: “During the past year, I have suffered as no other woman of my age has been called upon to suffer in the memory of this generation.”2

Who was to blame for Florence’s situation? In Florence’s thinking, it was anyone but herself! She blamed her overly strict parents, who never understood her. She blamed her teachers, who hated her for doing whatever she liked because she “chafed at the imprisonment of school.” She blamed the “scoundrels” of the Bedford Avenue Gang, “a crowd of worthless young wretches, who took advantage of my innocence and ignorance with a skill that was simply devilish.” She blamed Harry Casey, who “ought to be—well, there is nothing bad enough for him on earth.” She blamed Ed Watson, who “caused all her trouble.” She blamed Walter Brooks’s friends, who interfered with their relationship when they loved each other so much.3

Despite the Burnses’ attempt—or maybe because of it—to keep Florence out of sight, and hopefully out of mind, of neighbors and the press, the rumors swarmed like blowflies to a corpse. Her lawyer, Foster Backus, had to defend her constantly: No, Florence was not engaged to a Southern boy with a big red car. No, she was not being taken riding in elegant automobiles by other young men. No, she was not cavorting with friends at Manhattan Beach. No, she was not buying expensive designer fashions. No, she was not contemplating going on the stage. Her primary focus was to put the Brooks case behind her and try to reestablish her good reputation. She would lead a quiet life from then on.4

This plan worked until Foster Backus and his wife went on a vacation to Europe. With her primary monitor in absentia, Florence took matters into her own hands and effected her escape to freedom: She eloped with a young man ten years her senior whose past was very much like those Bedford Gang “scoundrels.” His name was Charles White Wildrick.

CHARLES WHITE WILDRICK

Charles White Wildrick was born in 1872, the eldest of four sons of a Civil War hero, Brevet Brig. Gen. Abram Calvin Wildrick, and his wife, Marion White Wildrick, both from prominent and accomplished families. Brevet Brigadier (really Colonel) Wildrick, a West Point graduate, had fought valiantly at the Battle of Petersburg. Even as a very young child, Charles had a tendency to be “wild and venturesome,” according to his mother.5

Two of Charley’s brothers followed their father’s footsteps to West Point and served in the army with distinction for over thirty years, as did his third brother after graduating from Princeton (eye problems kept him from West Point). All three boys attained the rank of colonel.6 Not so Charley, however, who dabbled in military service as some kind of “cadet and embryo officer” (but not at West Point), then abandoned that in 1888 at the age of sixteen to work for the New York Central Railroad as an auditor. From then on, according to his own account (and unable to be completely verified), he lived the life of a dime novel hero, a boy’s idea of a man: a swashbuckling, dueling, lady-killing, modern-day D’Artagnan, drifting from place to place, searching for adventure, seducing women, and spending as much as $100,000 (almost $3 million today) in the process. His relatives believed that he had stolen the family jewelry.7

Somewhere in his youth, Charley was given the nickname of “Tad” and from then on, that is what he was known by.8 The origin of it is a mystery to his family even today, although there is a feeling that it might have been after Abraham Lincoln’s son, who the president thought was like a tadpole because he squirmed and also because of his large head. Tad Lincoln was also a “wild and venturesome” child. Another guess is that it stands for “The Artful Dodger,” which accurately sums up Charley’s nature and his ability to talk himself out of the trouble he got into. For example, when he was twenty, Tad and two friends were in Salt Lake City and found themselves short of cash. They began begging money from passersby, after which they purchased beer. Three policemen saw the transaction and arrested them for vagrancy. Tad’s two friends were given the choice of being jailed or getting out of town, while he himself declared that he was simply borrowing the money that he got from the “donor,” not panhandling, and that two prominent doctors in town could vouch for him. The judge decided that he was “a gentleman in hard luck” who had “fallen among bad associates,” so nothing came of the charges.9

After his time with the New York Central, Tad went to work for the Southern Pacific Railroad in the West. He claimed he had saved Collis P. Huntington, one of the Big Four of Western railroading, from a serious fall, after which Huntington got him the position of assistant customs house agent. In Tulare, California (sometimes he said it happened in New Mexico and at other times in the country of Mexico), he shot two Mexicans to prevent them from holding up his train.10

When General Wildrick died in 1894, just after he retired from his thirty-seven-year career with the army, Tad inherited quite a bit of money (possibly the $100,000 he bragged of having gone through in a six-year period), after which he went to Bard’s Ranch on Bear River in Wyoming to work as a cowboy. This does not seem to have kept his attention for long because he soon ended up managing a hotel owned by a woman in Laramie. When the woman’s brother got wind of an affair between Tad and his sister, he challenged him to a duel. They were both such poor shots, however, that neither got hurt. On his way to Laramie, he had stopped off at the Republican Convention in Cheyenne and fought an eighteen-round boxing match with another cowboy.11

In 1896, now twenty-four, Tad went to Chicago, where he was hired as a buyer for Montgomery Ward. His manager there considered him a very smooth talker and a stylish dresser, but a young man who felt he was too good to have to do any work. Tad was about to be fired after eight months on the job, but he quit first. In 1898, still in Chicago, he signed onto a volunteer regiment preparing to fight in the Spanish-American War, but the regiment was never activated, so he went back to New York.12

That same year, 1898, Tad met the rich, beautiful, and cultured Jennie Armstrong of Louisville, Kentucky, who was visiting in Detroit, where she was also planning to buy some racehorses. When Jennie went away with him, her parents were furious and cut her off, but she and Tad eventually quarreled, and they parted on bad terms. (In 1900, desperate for money, Tad asked a friend to cash a sixty-five-dollar check for him, signed by J. F. Armstrong, his former girlfriend. The signature was forged and the check bounced, so Tad’s friend had to cover those funds with the bank.)13

Then Wildrick went to Marion, Ohio, where he connected with the young social set and was all the rage with the girls—much to the dismay of the boys. Tad Wildrick was the stereotype of the tall, dark, broad-shouldered, handsome man, who also had the power of seductive charm, which he used to his advantage, making every woman feel as if she were the most important one in the world.14

Soon after his sojourn in Marion, Tad met a married woman named Mary Cockley in Philadelphia. In June, she left her husband of five years and ran away to New York City to live at the Winthrop Hotel with Tad. Cockley followed them there, but Mary refused to go with him, so he filed for divorce and named Tad as a co-respondent. Soon after that, Tad “threw her over,” according to Cockley.15

Late in 1900, Tad Wildrick met twenty-seven-year-old Mabel Strong, the daughter of a wealthy man in Cleveland. Mabel’s mother had died in 1883, and her father remarried. There may have been some tension between Mabel and her sister on the one hand, and their father and his new wife on the other, as the girls lived with their paternal grandmother for several years. They also had inherited money from their grandfather, with Mabel’s share variously reported as $10,000, $13,000, $15,000, $40,000, and $80,000.16

Mabel was infatuated with Tad Wildrick to the point of folly. In January or February 1901, she “eloped” with him to New York City, where he convinced her that they had an oral contract of marriage because they recited vows in front of witnesses, although there was no clergyman or other official. They got a thirty-dollar-a-day suite of rooms at the Hotel Girard, registered as Mr. and Mrs. Gordon Sterling, and, by all accounts, proceeded to see how much money they could go through in the course of a day. Soon any money they had between them was gone. While they were assiduous about paying for the suite in the early days of their stay there, that eventually stopped, probably in March.

Either before they left for New York, or soon after they got there, Mabel contracted consumption (tuberculosis), but she was under the impression that it was in one lung only and curable. However, it became evident that she was getting worse and needed medicine, so their money was now diverted to paying for that. When Mabel began to realize that she might very well die, she went to a lawyer to have him draw up papers transferring all her assets to Tad and giving him power of attorney, but the lawyer—possibly suspecting some undue influence on Tad’s part—refused to do it. Earlier, Tad had bragged to friends that Mabel had given him $8,000 of her money, but she later said she had not. At the time she recanted, however, she was trying to save him from prison, so he was more likely telling the truth here.

In April, the Girard’s manager was getting impatient with not getting paid for the expensive suite. Tad did what he normally did in such situations: he gave him a phony check signed by a fictitious person, supposedly his brother, for $375. Then, without checking out, and also leaving some of their clothing behind, Tad and Mabel relocated to the Hotel Normandie, where she had stayed many times over the years and was well known. It was there that Tad was arrested on April 25, after his check to the Girard was discovered to be bogus. A guest at the Normandie, who knew Mabel’s father, told the hotel to give the young woman whatever care she needed and to put it on his bill.

When it was clear that Mabel was getting worse and would not survive for long, the Normandie contacted Clayton Strong in Cleveland to tell him his daughter was ill with consumption. He scoffed at this and said she was faking it, as she was “very resourceful” and only pretending to be sick in order to cover for Wildrick and get him out of trouble with her playacting. No, the Normandie personnel insisted, she really is dying of consumption and hasn’t long to live. Alarmed, Strong left for New York.

As weak and emaciated as she was, Mabel Strong got into a carriage with a nurse and went to the courthouse to see Tad: “I am Mrs. Wildrick. I want to see my husband before I die. Let me go to him, I implore you.” The magistrate agreed to let her go up to the second tier of cells, where Tad was being kept, but she had such difficulty navigating the stairs that she fainted on the way. Tad was brought down to her instead and allowed to hold her. The scene, as reported, was a melodramatic one, with Tad’s the only dry eyes in the house. Even the magistrate was touched. Mabel sobbed, “I know I am dying, Tad, but I could not die without seeing you again. I am come to tell you goodby, darling Tad.” Then she addressed the magistrate: “Have mercy, judge, on my husband. If my life is spared for another day, I will see, I swear to you, that every cent of this money will be paid.” She promised to bring the money on Monday, April 29, hoping to get it from her father. She was unaware that out of their affection for their friend at Fort Wadsworth, the late Col. Abram Wildrick, several army officers had paid off the debts left by his son.

Mabel fainted one more time and Tad was allowed to carry her to the waiting cab before returning to his cell. Tad was reportedly unmoved by this scene and insisted that she had no claim on him, that they were not married as she had said they were. “She was awfully stuck on me, poor girl,” was his comment, accompanied by a smirk. Needless to say, he did not come off well in the eyes of the press and the public for this callous attitude toward a girl who had given him everything, even getting out of her sickbed to plead his case.

In Tad’s slight defense for such callousness, there might be a somewhat benign interpretation of his lack of concern for Mabel’s condition. It may have been, on her part, a performance designed to elicit the very response that it got from the magistrate. There is no doubt that the girl was ill, but she and Tad may not have realized it was as bad as it soon became, despite her claims of being on the brink of death. She herself thought she only had consumption in one lung and believed it was curable. Some of the drama may have been the result of exaggeration, such as the two fainting spells, which was a quite common response of women in that time period to extreme emotional duress—like that of Mrs. Brooks on the witness stand. Mabel’s own father believed her capable of pretending to be ill, and Tad might have assumed she was putting on a show to help him out.

There was a great deal of sympathy for Mabel Strong, and both the magistrate and the trial judge were inclined to be lenient with Tad because of that and also because of his father’s reputation. But three communications doomed that inclination: a letter from a US Army colonel, who denounced Tad as a scoundrel; a letter from Tad’s former friend telling about the sixty-five-dollar forged check from 1900; and a telegram from the cuckolded Willard A. Cockley, who urged full prosecution of this “rascally hotel beat.” This, then, was obviously not Tad’s first brush with the law, the unfortunate result of an honest but misguided effort to procure medicine for his dying fiancée; rather, it was part of a pattern of behavior. On May 4, he received a six-month sentence to the penitentiary at Blackwell’s Island. He would never see Mabel Strong again.

When Clayton Strong arrived in New York to get his daughter, he was overcome with remorse for having disbelieved her illness. His statement to the press hints at past difficulties: “Whatever follies my daughter has done in the past, whatever sins she has committed, I have fully forgiven her. I only remember that she is my little girl, that she is in great trouble, that she is dying. I have not a single word of reproach for her, only a great yearning. But I would gladly kill the man. A more despicable wretch never drew breath. He is absolutely without a shred of honor. … He is in for the penitentiary, but I wish he was to sit in the electrical chair.” Strong hoped to take his daughter home to Cleveland, “where she was so happy as a girl.” But she grew weaker and was taken from the Hotel Normandie to St. Luke’s Hospital, too ill to be moved to Cleveland.

Mabel Strong proved to be strong indeed. While her doctors were predicting that she had but a few days to live back in late April, she lasted until July 14, 1901, dying on her sister’s birthday. “Tell Tad I loved him,” she commissioned her father, who was at her deathbed. These were her last words. When newspapers recounted the story and praised her loyalty, they also showered Tad with such epithets as “worthless,” “scapegrace,” and “hotel beat.” Clayton Strong took his daughter’s body back to Ohio, where she was buried in a family plot in Fredericktown, next to her mother.

Is it any wonder, then, that the press was deliriously joyful at the news of a marriage—an elopement, no less—between Charles White Wildrick and Florence Burns? Two sensational histories in one package!

THE COURTSHIP OF FLORENCE BURNS

Tad Wildrick would have finished up his six-month sentence around November 4, 1901. Supposedly, he soon made the acquaintance of Florence Burns and asked her to marry him, but at that time, she was heavily involved with Walter Brooks and had no eyes for anyone else. In another month, the relationship would deteriorate, but in November, she probably believed she would marry Walter. Although the newspapers claimed that Tad was a member of the Bedford Avenue Gang, this is unlikely. For one thing, he was about ten years older than most of the members of that group, and, for another, he was not one to join such an organization and submit to a leader and a set of rules. Tad Wildrick followed nobody’s directives but his own. In all the publicity given to this gang during the Brooks-Burns case, not once was Tad Wildrick’s name ever mentioned, despite the constant references to other members.

It’s obvious that the paths of Tad and Flo crossed at some point, but it is unclear whether it was before or after the Brooks murder. They both stuck by the probably fictional story that they had been friends for a long time and that he had loved her for many years, but when would he have had the time between his multi-state adventures and his prison sentence? Florence claimed that during her “imprisonment” in her Brooklyn home, she sought his advice as to how to gain her freedom, that maybe he could find her a job that would get her out of the house.17 However, she had exploded in anger at Walter for this same suggestion, declaring that she would never “ruin herself by working,” so there most likely was no discussion of job-seeking at their meetings. At that time, Wildrick may have been living in Brooklyn and, once Foster Backus left for Europe, Florence was probably taking advantage of his absence by either boldly leaving her home or sneaking out of it to meet Tad.

At some point, the idea of marriage came up, and there is no doubt that Florence would have grabbed at any chance to get out from under her parents’ stifling repression. She depicted herself and Tad as two lost souls in that they were scorned and misunderstood by the world—“the playthings of fate,” she called them. Tad professed to take on the cause of proving her innocent of the murder of Walter Brooks. He would be her knight in shining armor. “I will devote my whole life to clearing this sweet girl’s life of the cloud of this infamous accusation,” he declared.18

The marriage was supposedly a sudden “Why don’t we get married?” impulse, but it was probably planned in advance. In fact, Florence had quarreled with her parents shortly before that—maybe deliberately—and stormed out of the house, never to return. A week later, reporters sought the Burnses’ reaction to the marriage, but they knew nothing about it. Fred Burns was shocked to hear it and refused to comment: “I have nothing to say. I will stick to my policy of saying nothing, the same policy I have always maintained concerning my daughter.”19

Shortly before 9:30 P.M. on Wednesday, November 26, 1902—the day before Thanksgiving—Tad and Flo showed up at the Thirty-Fourth Street Reformed Church in Manhattan, where the regular weekly meeting was just breaking up. They told the minister, Rev. John H. Elliott, that they wished to be married. Elliott thought it odd as the hour was late and they had brought no witnesses, but the prospective groom answered his questions “in a straightforward, manly way,” so he summoned two parishioners to serve as witnesses. The couple signed their names as Charles White Wildrick and Florence Wallace Burns. Elliott did not recognize either name, but one of the witnesses, twenty-three-year-old Edythe Mariani, thought she did: “Wouldn’t it be funny if the bride was the Florence Burns of the Brooks case?”20

When Mariani and the other witness, James Cromie, discovered the truth a day or so later, they were angered and upset at having unwittingly played a role in the marriage. Mrs. Mariani was outraged: “My daughter is horrified at this publicity. She does not know Florence Burns, and was a witness to the marriage lately at the request of Dr. Elliott.” It was the first of many indications that, although Florence was dismissed as a murder suspect by a judge and the coroner, and to thunderous approval in the two courtrooms, most people believed she had killed Walter Brooks.

Reverend Elliott said that he never connected the bride with the woman accused of murder, and he supposed his fellow ministers would criticize him for it. But, he argued, if he had not married them, someone else would have. Nonetheless, he capitalized on his brief fame by giving an address at a conference on supporting a bill to punish adultery. He was known as the minister “who recently married Florence Burns to Charles W. Wildrick.”21

Editorials around the country weighed in on the probable success of the Burns-Wildrick marriage. Typical of these was one from Montana: “Will they live ‘happily ever after’? They may. But it’s a 50 to 1 shot that they don’t.”22

FLO’S FOLLIES

Before he left for Europe, Foster Backus addressed the issue that most intrigued the public: What will Florence Burns do now? Would she go on the stage? Backus had assured everyone that pursuant to a family consultation (likely without input from Florence herself), it had been decided that Florence would not go on the stage but instead live a more subdued life. She should not attempt to “coin her notoriety into money.” “As to Florence’s future, she has now seen the error of her ways, and is a changed girl. She never was a really bad girl, but she liked gay life. It appealed to her. She is dignified and reserved. The examinations in this case have enlightened her as to the kind of men she has been going with. They have revealed to her what she would have become if she had continued to live the way she had been living.”23

Quite possibly, Backus’s speech was intended to send a message to his client, who did not seem to be so inclined to “live a more subdued life.” But the Brooklyn Daily Eagle urged Backus to press home this point to Florence—that although most people in the community were on her side during her hearings, its “moral sense … will rise in protest against any attempt to make capital for her out of the tragic publication of her shame. This is a time for plain talk.”24 In other words, we may have been on her side because of the circumstances (the Unwritten Law), but that doesn’t mean we will support her flaunting herself on the stage through notoriety acquired by the death of that young man.

Foster Backus and the community at large reckoned without the independent and headstrong nature of Florence’s character. No sooner was Backus off to Europe than she arranged her liberation by eloping with Tad Wildrick and, two weeks later, signing a vaudeville contract with Irving Pinover, a dramatic actor and former reporter with William Randolph Hearst’s “yellow” newspaper, the New York Journal. A skilled agent, Pinover had successfully managed the comedy team of Weber and Fields, famous for its slapstick and satire, which included a sketch done in the German dialect.25

The plan was for Florence to begin her vaudeville career with a tour of twenty weeks, to begin in New Jersey or New York, then to the Midwest cities, but instead it was decided that she should start in her hometown of Brooklyn. Her performance was to stay completely away from the Brooks case and would consist of songs, little sketches, and maybe some solo dancing. It was an interesting omission in that theatergoers would expect someone involved in a high-profile murder case to sate their curiosity by discussing it. Someone smarter than Florence—Tad? Her agent?—must have reminded her that there was no statute of limitations on murder and, guilty or innocent, she could say something onstage that would trigger an arrest. Since there had been no trial, double jeopardy did not apply.

Florence was to get $1,500 even though nobody knew if she could act or sing. How did the community react to this news? On the joke page for Friday, December 12, 1902, the Eagle included a jibe at Florence in the guise of a conversation between two women:

No. 1: So, Florence Burns is going on the stage again, eh?

No. 2: Again? Has she ever been on the stage before?

No. 1: Well, she played an important part in a considerable farce a few months ago, I believe.26

Most people believed she had killed Walter Brooks, and most did not mind that she got away with it—probably a majority even believed he deserved it—but making money off it, whether she was going to talk about it or not, was crossing a line. However, for her agent and for the proprietors of the houses she was booked in, the only success was not in the quality of her performance but in how many paying customers would line up to see her. When Florence and her new husband showed up to watch a play at a local theater, the audience was much more interested in them than they were in what was happening on the stage. Now, added to the titillation of a sensational murder case was the romantic derring-do history of Tad Wildrick. This fascination would carry over to Florence’s own stage appearances.27

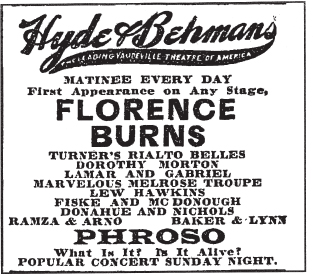

It’s a good thing it did, too, as her debut at the very popular Hyde & Behman’s theater was a disaster. The managers had no idea what she was going to do or whether she could sing or recite a monologue. She had not rehearsed at all either. Hyde & Behman’s, however, was not in the least concerned about this because they knew she would be a big draw. In fact, even though it was universally discussed and decided that this vaudeville career was a bad move on Florence’s part, most of those who criticized her still showed up to see her.28

By this time, with the vaudeville contract on top of Flo’s elopement with a man who had only the year before been released from prison, in addition to her autobiographical article written for Hearst’s Journal criticizing her parents, the Burnses had washed their hands of her and cut her off from the family.

On the day of Florence’s inauspicious debut, Foster Backus was on his way home from Europe, ignorant as to how far his former client had regressed since he last saw her, and there was much speculation as to how he would react to it.29 History, however, is blessedly silent as to this.

The vaudeville ad promoting Florence Burns’s Brooklyn appearances (Brooklyn Daily Eagle, reprinted in www.newspapers.com and used with permission from www.Ancestry.com)

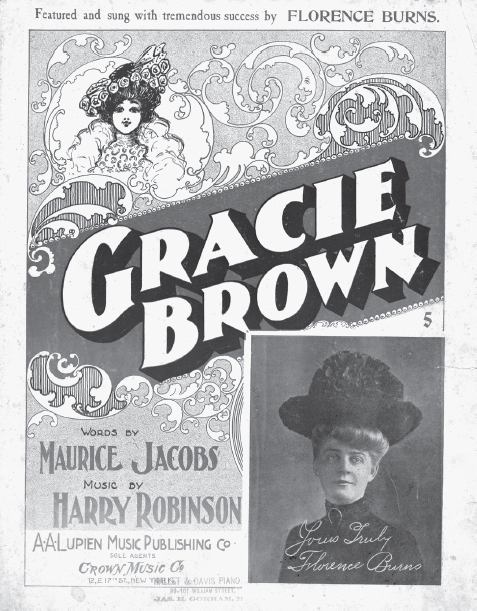

The debut consisted of two performances, one in the afternoon and one in the evening. Tad hung about in the wings to give her encouragement. The crowd, consisting mostly of women, applauded madly before Florence had even opened her mouth. For the afternoon session, she began with an imitation of that kangaroo walk that was the current craze and then was to sing a current popular song called “Gracie Brown (A Sly Naughty Girl)” by Maurice Jacobs (lyrics) and Harry Robinson (music). It was a somewhat suggestive song insinuating that Gracie was a flirt who took money from the boys, then left town:

1st verse:

Gracie Brown was a maid with a sly naughty wink was Gracie Brown.

She wore a straw hat and a dress that was pink did Gracie Brown.

She lived in a village where boys there were few

But the boys that were there had hearts that were true

And now they all sigh with a tear in their eye for Gracie Brown

Chorus:

Gracie Brown, she is out of town

She’s the kind of girl that is hard to find is Gracie Brown.

We’re all blue and we sigh for you.

If you change your name we will know you the same as Gracie Brown

2nd verse:

Reuben Glue came to town and his whiskers were pink, met Gracie Brown.

She’s a nice little girlie I think is Gracie Brown

He is waiting for Gracie, she said she’d be back

‘Cause Gracie was honest, he gave her his cash

But he’ll see her no more, Gracie’s gone to the shore,

Sweet Gracie Brown. (Repeat chorus)30

Florence’s performance was “a dismal and pitiable failure.” Her voice was so weak that she could not be heard at all, not even in the first row. She tried three times to get this song right, but she kept forgetting the words. She had not practiced and didn’t even have a copy with her on the stage, and then she had to start over. Finally, the band leader handed her a copy, but she wadded it up without looking at it and left the stage. The stage manager mercifully brought the curtain down and not even the audience’s raucous calls for Florence to come back and finish could change her mind.31

Although newspaper reports said she was not nervous, only unprepared, it was obvious that Florence was a victim of stage fright. Anyone who has ever dreaded speaking in public has known that breathless feeling where the lungs don’t seem to fill up completely and that powerlessness to project the voice. A few times, when Florence forgot the words to the song, she looked at Tad in the wings and laughed—again, a sign of self-conscious nervousness and not, as many felt, her failure to take the performance seriously.32

For the evening show, Behman did not want to risk a repeat of the afternoon debacle and arranged for a group of nine female singers—Turner’s Rialto Belles, fresh from a tour in Pennsylvania—to come onstage with Florence and be sort of a warm-up/backup act. The ensemble was billed as “Turner’s Rialto Belles and Florence Burns,” although, strictly speaking, Florence did not belong to this group. The Belles, managed by Frank Turner, had a singing and dancing routine consisting of three presentations, after which Florence was to join them on the stage. But Behman sent her out after the second act, which threw the Belles off, as they had not been prepared for this interruption.33

For this performance, Florence was decked out in a “very becoming dove-colored gown, trimmed with immense turquoise bead flowers, mingled with silver flowers. The gown was cut very low and at the shoulders were trimmings of black chiffon.” She accessorized her outfit with black gloves and a black hat.34

Florence came out, “swinging her arms and moving her body like a village belle trying to be real graceful,” but something about this entrance—was it viewed as arrogant? seductive?—was completely off-putting for the audience. They gave her the silent treatment: no clapping, no shouting, no sound at all. She started “Gracie Brown” but still did not know the words, or else they were frightened right out of her head. As she stopped and started several times with the same four words, the orchestra frantically tried to keep up. By this time, the audience took pity on her and there was a smattering of applause to encourage her to get through it, but she could not. Nor could she be heard any more than at the afternoon performance, with her thin, reedy voice. The reviews were merciless: “It was like some five-year-old child giving an exhibition of its prodigious skill.” “The only thing she had going for her was beauty.” “Very ungraceful in her movements.”35

Florence left the stage before the song was finished, singing as she left and with the same sauntering gait she had used for her entrance. There was very little applause, which lasted for mere seconds. The stage manager tried to coax her back onto the stage to finish up, but she would only go back for a curtain call.36

After a second disastrous performance, Behman decided there might not be any more singing if it did not improve, but only sketches and maybe some dancing. Reporters were astonished to hear that the theater would continue her contract for the week, but the manager was more practical: The theater was turning hundreds of customers away because everyone wanted to get a look at the infamous Florence Burns.37 Nobody was interested in the other performers—the full house was for Florence alone, as if she were a freak in a circus sideshow. Why would it matter that her performances were flops? Even a lukewarm Keith-Albee Manager’s Review of Flo’s debut would not have discouraged anyone from attending:

Turner’s Rialto Belles and Florence Burns: The Rialto belles consist of eight women and a leader who render three songs with figure dancing and light effects. The act was a good deal of a disappointment and failed to carry. The introduction of Miss Burns at the close of their set proved to be an unprecedented drawing card, filling the house at each performance with the high class audiences, who watched and listened to her short act with engrossed attention. Miss Burn’s [sic] appearance was remarkably prepossessing. Used full stage; time 17 minutes.38

Hyde & Behman now had a potential lawsuit on its hands from the Turner’s Rialto Belles, who had their sets interrupted without warning. Their manager claimed a breach of contract for that and for what he saw as Florence’s “stealing their applause” in coming onto the stage between their second and third acts. (“Stifling their applause” would be more accurate, as the audience had shown its disapproval of her flaunting entrance with a crushing silence.) Frank Turner threatened to quit if changes were not made, but they were not. Behman’s reaction to Turner’s threat was to get the Newsboy Quintet for Flo and tell Turner he could take his Belles elsewhere. The Newsboy Quintet was an enormously successful act created for Hyde & Behman’s in 1896, consisting of five teenage boys dressed as “newsies” in torn, ragged clothes who sold newspapers and sang popular songs. As boys grew too old for the part, they were replaced by others, much like Menudo, a similar band of the 1970s and 1980s.39

Frank Turner had one more card to play: he consulted the notorious law firm of Howe & Hummel, the most colorful, creative, and corrupt lawyers in New York City—and the most successful. From 1869 to 1907 (when Hummel was convicted of suborning perjury and sentenced to a year in prison; Howe had died in 1902), they represented gangsters, madams, murderers, thieves, and the vaudeville/theater community. The very tall, very corpulent William Howe generally handled the criminal aspect, while the short, small, dapper Abe Hummel was a master at taking care of theatrical cases. Howe had represented, among many other famous defendants, Martin Thorn for the murder and dismemberment of Willie Guldensuppe, Carlyle Harris for the poisoning of his wife, and George Appo, the boy pickpocket. Abe Hummel’s most notable client was probably Evelyn Nesbit, the “Gibson Girl,” after her husband, Harry Thaw, killed the architect Stanford White in an “Unwritten Law” case that was prosecuted by William Travers Jerome.40

Although Howe & Hummel were not above lying and cheating to win their cases, Abe Hummel did have some sound advice for Frank Turner: he was to have his girls ready, willing, and able to perform every night of their obligation so that Behman could not claim they had breached their contract by not appearing. Hummel suggested that Turner might also have a suit because of the damage to his professional reputation. Behman’s response was to laugh at this and put a false spin on it. The Belles weren’t really all that good, he claimed, so he had Florence go out on the stage to help them out!41

Somebody with tongue planted firmly in cheek wrote a letter to the editor with a suggestion of a very melodramatic sketch for Florence and her husband to perform, with several fat women planted in the audience to sob on occasion. Fat women are best, the author wrote, because their voices are “more strident” than those of thin women, and thin people, in general, are less sympathetic than fat ones.42

At Newburgh, New York, just fifty miles up the Hudson River from New York City, Florence was billed as “the most persecuted and most beautiful young woman in America.” But approximately five hundred people waited outside her hotel and jeered her when she came out to get a cab to the theater.43

Florence’s eventual debut in Manhattan, after appearances throughout New York State and New England, was in February 1903, at Proctor’s Twenty-Third Street Theater, one of several Proctor’s theaters in New York City and Newark, New Jersey. There, she was “The Persecuted American Girl” and still singing “Gracie Brown,” presumably with some improvement. Among the acts appearing at Proctor’s with her was a standard sampling of vaudeville acts of the time: a Japanese troupe of magicians and illusionists; trick bicycle riders; a blackface monologue, probably by a white man, but then also a “colored singing comedian.” Including Florence’s, there were to be a total of nearly thirty acts—a lot of entertainment for a Gilded Age audience!44

Vaudeville at the turn of the twentieth century was enjoying a surge in popularity, although it had been around since after the Civil War. But with an increase in both public and private transportation options available, as well as the establishment of the amusement parks at Coney Island and elsewhere, Gilded Age audiences were enamored of variety shows. There were also the dime museums (cheap variety shows for the working class, a level below vaudeville) and the circus with its sideshows.45

The staples of vaudeville and other variety acts were the minstrel shows with white men in blackface, magic tricks and optical illusions, short skits, dancing and singing, and—always—actors and actresses with strong ethnic accents, which audiences found hilarious because of the influx of immigrants into the cities. It was an occasion for nonethnic viewers to laugh at the foibles of the newcomers, with the most common accents being Irish, German, Italian, and Yiddish.46

Yet another factor driving the proliferation of variety shows was the increase of factories and shops in the cities, which had the effect of luring young men and women from the farms. In their leisure hours, they went in search of entertainment not available in rural areas. In an ironic coincidence, one of these young women who exchanged farm life for the factory was named Grace (but not Gracie) Brown. Her murder in 1906 by a boyfriend who refused to marry her when she got pregnant would form the basis of Theodore Dreiser’s An American Tragedy. And, in a further irony, if Grace had killed Chester for not salvaging her honor with marriage, she would have been acquitted under the Unwritten Law. Chester, having no such defense, was executed in 1908.47

By the summer of 1903, Florence was appearing at beach venues: Rob’s Casino Theater at North Beach in Brooklyn and Morrison’s Casino at Rockaway Beach on Long Island. She had never joined the Actors’ National Protective Union, which caused a problem for her at Rob’s Casino when the other actors, actresses, and musicians refused to work with her. Consequently, she was dismissed.48

However, at Morrison’s at Rockaway Beach, Florence was the star attraction—so much so that a nearby rival theater was losing business, until the proprietor had a brainstorm. He had a large poster printed up saying, “FLORENCE BURNS” and, on top of that, in very tiny letters, “Pauline Brown will give an imitation of.” Florence, accompanied by Tad, went to the local police court to get a restraining order against the rival establishment, but the magistrate informed her that it was a civil matter, not criminal, and she would need to get an injunction against the proprietor, as well as Pauline Brown, from the proper court.49

In the fall, the proprietor of Morrison’s got the bright idea of featuring Florence with the temperance scold, the hatchet-wielding Carrie Nation, famous for attacking saloons with her weapon. The juxtaposition of the fifty-seven-year-old morally upright matron and the twenty-one-year-old morally challenged Florence Burns Wildrick was too tempting for him to resist. The wonder is that Mrs. Nation actually agreed to it! She saw it as an opportunity to lecture against alcohol and tobacco, but she was unprepared for the two-pronged shock that was in store for her.50

In the “green room” while she was waiting to go onstage, Mrs. Nation encountered another performer, the perennially popular vaudeville singer/actress Lottie Gilson, on the downside of her career at the age of forty-one. Nation, never passing up an opportunity to preach, told Gilson that she should never marry a man who smoked cigarettes (no mention was made of pipes or cigars, so possibly they were not on the Carrie Nation Hit List of Forbidden Indulgences). “If I do,” the younger woman responded, “he will buy his own. He won’t get any of mine.” Nation was so shocked that Lottie Gilson was a smoker—and admitted to it without shame—that she shrieked, “Let me out of here!” and remained outside on the theater grounds until the time of her appearance with Florence.

When Carrie Nation saw Florence’s low-cut dress, she experienced another shock and refused to go on with her dressed like that until someone put a shawl on Florence to cover up the offending area. “You’re a faker,” Florence said. “Maybe I am,” Nation responded, “but I’m no woman to appear with such a woman with no more clothes on than one of the park statues.” She took out her Bible and waved it at Florence as if warding off evil, gave her scheduled lecture, and collected fifty dollars for it. In the end, like Florence Burns and Lottie Gilson, Carrie Nation was herself an entertainer.

Carrie Nation had to know who Florence Burns was and probably had some inkling as to her vaudeville act. Quite possibly, she realized that appearing on the same stage with her would provoke the very kind of confrontation that resulted, and she would have yet another opportunity for a “teachable moment” that would find its way into the press. Otherwise, it would have been more in keeping with Nation’s straitlaced persona to have given lectures, not on vaudeville, which was solely for somewhat low-brow entertainment, but in more high-brow venues such as formal lecture halls or Chautauquas.

So it went, until December 1906, when the conflict between the desires of Flo and Tad came to a head.

THE BREAKUP

At the beginning of January 1907, Florence left Tad Wildrick and moved back in with her forgiving parents, now living on Putnam Avenue in Brooklyn. He was back to his old habits of sleeping with other women, in particular one whom Flo seriously thought of suing for alienation of affections. Tad begged her to divorce him, which his adultery gave her the right to do under the divorce laws. But he could not file on his own because he had no statutory grounds, which at that time in New York State were adultery, cruel and inhumane treatment, imprisonment for three or more years after the marriage, and continuous abandonment for one or more years. Flo had committed none of these offenses—not yet, anyway.51

If Tad Wildrick really had someone he wanted to marry at that time, he would have done well to force Florence’s hand by not giving her any money. Instead, he chose to send her a payment each week with no legal obligation to do so. When he stopped the payments a year and a half later, Flo suddenly had the motivation to file for divorce, which she did in April 1908, on the grounds of infidelity (although she did not name anyone as co-respondent). She asked for twenty-five dollars a week for alimony and $200 for attorney’s fees.52

WHAT SHE SAID

In her filing papers, Florence claimed that, apart from Tad’s adultery with many women, he hit her, neglected her, and spent large amounts of money on these other women, while she suffered from a lack of funds. She claimed she was a “physical wreck” and needed medical attention because of having to deal with Tad’s “immoral behavior,” which she had finally had enough of. She had no money for whatever medicine she needed, although Tad could easily support her, as he was living “very comfortably and luxuriously.”53 Here, she seems to hint at having contracted a venereal disease.

WHAT HE SAID

Tad actually had a bigger list of complaints against Flo than she had against him. While some of them may have been exaggerated or created out of whole cloth, the very tenor of the first one set out in his countersuit smacks of Flo’s vindictive nature. Tad worked for an advertising company, where Flo frequently sent postcards accusing him of things such as being a “morphine fiend” and other “scurrilous statements” that the company’s clerks and Tad’s employers could read, since the postcards were put in a common area. Contrary to Flo’s assertion of his living richly, Tad insisted that he earned only fourteen dollars a week. He had tried his best with her and even sent her to Liberty, a resort town in the Catskills, for four weeks in 1907.54

Tad accused Flo of frequently being with “disreputable company,” although he did not give any specific examples of this, and of being addicted to gambling and staying at gambling resorts. Flo was earning good money on her own, he asserted, even more than his own fourteen dollars a week, with her “fancy exhibitions of roller skating” at a Manhattan rink.

Tad claimed to have taken good care of Flo. We know that he accompanied her to her vaudeville appearances and was generally a support system for her there. But, he asserted, her harassment of him at his office was causing him “mental anguish.” He denied ever having used morphine in his life.

Florence’s monetary demands were scaled down quite a bit by the judge: from twenty-five dollars to five dollars per week for alimony pending the divorce trial and from two hundred dollars to fifty dollars for attorney’s fees.55

Florence must have been chafing at having to live with her parents and was looking forward to having some funds to find her own room somewhere. At some point in 1909, she moved out of her parents’ Brooklyn home and began a succession of Manhattan habitations. Unmoored from any settling influence—her parents or her husband or her vaudeville career, now mostly defunct as the novelty of Florence Burns had by then worn off—Florence was adrift and on her own. She began a downward slide that primarily consisted of heavy drinking, then petty scams to support her habit, then soliciting money from men, which led to exchanging sex for money and drinks: prostitution in spirit if not in a more formal arrangement.56

Gladys Burns, who had also been living at home at age twenty-four, suddenly eloped to New Jersey to marry twenty-four-year-old Harry West Mettais in Hoboken on November 9, 1909. Once again, the Burns parents were caught off guard at the marriage of a daughter.57

Mrs. Burns, despite all the heartache caused by her older daughter, was sending Florence weekly money by registered mail, usually three or four dollars, but sometimes more if she had it. Florence discovered, to her dismay, that the Unwritten Law did not help her so much outside of court. When some of her landladies saw the return address on Flo’s mother’s envelopes as “Burns” and addressed to Florence Wildrick, they put two and two together and realized she was “that” Florence Burns. Consequently, she was evicted from a couple of boardinghouses, and from then on, her mother had to put her maiden name (Von derBosch) in the return address.58

Florence’s life spiraled further downhill. She became adept at getting men to buy her drinks, supplies, or just give her money, blaming the troubles in her past for her current situation. Nothing that happened to her was ever her fault, and she seemed to be immune to any self-examination as to why her life was out of control.

Then Florence met two men who would change the arc of her life in a significant way: Charles W. Hurlburt and Edward H. Brooks.