THE POST-WAR ITALIAN FILM INDUSTRY

The rise of Italian genre cinema and its venerable golden age was assisted by financial incentives and funding awards. It was not simply a concerted effort to counter Hollywood’s cultural dominance and favour homemade product. Producers and other executives wished to expand their horizons. Lucrative contracts and opportunities do not require borders, after all, and there would be clear and welcome advantages to international co-productions and distribution deals. Rome did not earn the moniker ‘Hollywood on the Tiber’ for nothing. Foreign dough – American, French, German and Spanish – was most vital to Italy’s flourishing success during this period. American producers began buying up low-budget genre pictures to flog at home. Turning a profit wasn’t difficult. Black Sunday became a stellar success in the United States when released in 1961. ‘From 1957 to 1967 US companies spent approximately $35 million dollars a year to finance or buy the distribution rights to Italian films, or to make their own films, with Italian studios as their production base’ (Baschiera & Di Chiara, 2010: 11).

Galatea, the production outfit that financially backed Bava’s film, branched out to the American market when they sold Hercules to producer Joe Levine and subsequently earned an advance to provide a sequel. ‘From then on, even smaller producers knew that there existed American distributors who were willing to pay an advance for genre movies, and even for genres that Italian audiences did not like’ (ibid: 33).

In 1956, the chief executive officer of Titanus, Goffredo Lombardo, announced the crisis facing Italian cinema was due to a heavy dependence on making pictures for the home audience. He came up with an idea to bolster production as well as profits:

While lowbrow pictures were to be made just for Italian spectators with Italian funds, medium-sized productions should instead be made with European investors and should be aimed at the European market; eventually, Italian cinema should also attempt large productions in partnership with American studios, with the goal of reaching a global market (ibid: 32).

The boost in feature production during the 1950s was partly due to the inviting cultural/economic protection model by Christian Democrat politician, Guilo Andrelotti. A loan fund was set up which was ‘fed by taxes on foreign film dubbing, an automatic tax refunds system (about ten percent of the film’s gross) and a special norm (introduced in 1951) which forbade the export of 50 per cent of the gross made in Italy by every foreign film, thus forcing Hollywood to invest part of their income in Italian productions’ (ibid.).

ITALIAN HORROR

A major accusation that has followed Italian genre movies around for decades, like the fetid stink of a zombie from one of Fulci’s grotty horror picture shows, is that it merely existed, even thrived like a parasite, on an endlessly crass appropriation and replication of popular – and especially Hollywood – genres. Nowhere was this accusation more alive than with the Spaghetti Western. In his seminal study of the genre, Spaghetti Westerns: Cowboys and Europeans from Karl May to Sergio Leone (1981), Sir Christopher Frayling explained the whole system’s inner workings:

Between the early 1950s and mid-1960s, Italians (and later Spanish) producers working at Cinecitta Studios had made various attempts to anticipate (or exploit) the taste of the Italian urban cinemagoers, by hijacking entire film genres – the most notable being the ‘filmfumetto’ (1948–1954), the farcical comedy, often of a dialect kind (1955–1958), the ‘sword and sandal’ epic (1958–1964), the horror film (1959–1963), the World By Night or Mondo Cane genre (1962–1964), and the spy story derived from James Bond (1964–1967). Many of these Cinecittà films were made in assembly-line circumstances which resembled those of Hollywood B features, or even TV series: shooting schedules which seldom over-ran a five-six week was normal; budget averaging $200,000; the more solid sets used over and over again; only two or three takes per shot; post-synchronised sound and dialogue tracks (even in Italian versions). (1981: 68)

Italians loved movies during this fallow period. But they loved certain kinds of movies. From Milan to Naples to Brindisi way down in the boot heel south, patrons went to the pictures as a recreational pastime more than any other European nation during the post-war years.

A major reason, perhaps the major reason, for Italy’s failure to establish its own variation on the horror movie was on political grounds. Mussolini’s reign as dictator saw the industry stifled by fascist meddling. The government banned American films outright in 1938. Yet in an exceedingly perverse way the fascists established, in these years, the Istituto Nazionale LUCE, the Centro Sperimentale di Cinematografia and built world-class facilities – Cinecittà – as well as set up ‘cinema caravans’ that toured rural and remote regions of the country. The sound era also saw the establishment of post-dubbing the soundtracks, by which the authorities could easily control the information imparted; mostly importantly, the dialogue. British director Peter Strickland made an entire film centred on this industry peculiarity in 2012’s Berberian Sound Studio.

One would expect a country such as Italy, the land that posited the bloody spectacle of Christians being thrown to lions and/or gladiators in the coliseums of its vast empire counted as a thoroughly entertaining afternoon out, that gave us bloody Renaissance paintings and the eternal degradation and phantasmal terror in the Inferno and Purgatory of Dante Alighieri’s The Divine Comedy (written between 1308–1321), to have been a prime candidate to pioneer horror cinema all on their own. Violence is Italian art, as Lucio Fulci quipped.

THE MONSTER OF FRANKENSTEIN

Prior to the Italian Gothic boom, which lasted from roughly 1960 to 1965, only the lost silent Frankenstein adaptation sticks out from the crowd. In 1921 Eugenio Testa directed – a whole year before F.W. Murnau delivered his unofficial Dracula (Noserfatu: A Symphony of Horror) – Il Mostro di Frankenstein (The Monster of Frankenstein) from a script by Giovanni Drovetti. This, however, was not the first Frankenstein adaptation to grace the silver screen. There were two silent features produced in 1910 and 1915, one an Edison production and then Life without a Soul, directed by Joseph W. Smiley, respectively. Both of these are American productions. Il Mostro di Frankenstein was a German-backed effort made in Italy by Testa (1892–1957), an actor and director.

Needless to say, it doesn’t get any more Gothic than Mary Shelley’s acclaimed novel inspired by a nightmare experienced during her stay at the Villa Diodati in June 1816 – an infamous summer that has entered into literary lore. Il Mostro di Frankenstein starred Linda Albertini, Luciano Albertini (credited as Baron Frankenstein), and Umberto Guarracino took the role of ‘The Monster’. Guarracino was a strongman type in several Peplums.

The film posed serious problems for the Italian censors and forced the makers to cut the picture so drastically that the release length was a mere thirty-nine minutes. Il Mostro di Frankenstein was reduced to the status of a featurette.

As a further point to the sensitivities stoked in general by screen adaptations of Frankenstein, James Whale’s version (1931)suffered at the hands of the censors a decade later when the newly established ‘Production Code’ was in force. The re-release of Frankenstein, prior to The Bride of Frankenstein (1935), excised the line: ‘Now I know what it feels like to be God!’

The intensity and amount of scene removal from Testa’s film by the censors suggested the material was simply deemed too strong for the audience to stomach. The Catholic sensibility could not take such an affront to their teachings and way of life by some entertainment venture. As with a vast majority of movies produced during the early years, Il Mostro di Frankenstein is today considered a lost film. A production still is extant along with a couple of posters. One piece of promotional material advertised a screening at the Selection Georges Petit, 37, Rue de Trovise, Paris. The other announced the film, advertised in 1926 (so still around five years after release), playing with a Hal Roach directed two-reeler starring Harold Lloyd. What on earth to make of that double bill? After that, Il Mostro vanished into the murky abyss of history. It is worth noting that at the bottom of the 1926 promotional poster there is an advertisement for a peplum titled Galaor contra Galaor, made in 1924, and a film attributed to Eugenio Bava.

A MAJOR STEP FORWARD: I VAMPIRI

The theatrical release of I vampiri (known internationally as The Devil’s Commandment and Lust of the Vampire) on 5th April 1957 gave subsequent Italian Gothic a foundation on which to build its place in history. Shot in the autumn of 1956 it preempted Hammer’s foray into Gothic by a year even though the story is not set in the 19th century and neither is it exclusively Gothic in tone. Yet Freda and Bava might as well have declared on the studio floor at Titanus, St. Peter-like, ‘Upon this film, we shall build Italianate horror’. ‘With I vampiri/The Devil’s Commandment the Italian gothic horror film emerged fully formed and apparently out of nowhere’ (Hughes, 2011: 155).

I vampiri is inarguably the bedrock, the grandfather, the instigator of Italian horror cinema. It was never heralded as such until many years later, and flopped when sent out to the picture houses of Italy. Neither is there much in the way of gore, eroticism or romance. Compare it to Hammer Films’ output a year or so later and I vampiri is positively chaste. It has been written Freda’s original concept would have been more gruesome than the finished product, which was revised extensively by Bava, who worked at the behest of his paymasters, as well as basically saving the entire film from disaster. The major stumbling block for any more films in the immediate aftermath of I vampiri’s Italian release – that worked against any prospective foray into the genre – was the salient fact that movies of this type that derived from the studios of Rome were not taken at all seriously by filmgoers, who thought the whole notion of ‘Italian horror’ quite off-putting. It was a cultural thing; a matter of indifference and sense of cultural inferiority. Freda, in a reminiscence included in the Arrow Video Blu-ray release booklet of Black Sunday, recalled:

The first horror film I did was I vampiri in 1957. The film did not go down too well, it was perhaps a little ahead of its time for audience tastes, but above all the people who followed that genre of cinema only did so if the film was American. I was there at San Remo for the premiere. As people filled into the cinema, they stopped to look at the photographs and the names. When they arrived at mine, they exclaimed: ‘My God, it’s an Italian film then!’ Then they left. (2013: 28)

When it came to making Caltiki – the Immortal Monster, in 1959, Freda decided upon a cunning ruse. He would change the names of actors and the production crew in order to fool the audience into thinking they were watching a foreign movie.

HOW I VAMPIRI CAME INTO BEING

Riccardo Freda (1909–1999), an Egyptian-born Italian national, had been involved in the film industry since 1937. The story goes that he made a bet with two producers that he could shoot a picture in twelve days. Freda had met Bava on the set of Spartaco in 1953 (US title: Sins of Rome). They clicked over a mutual passion for the arts. One day, Mario invited his new buddy Riccardo back home to look at Eugenio’s wax sculptures and they hit it off. A couple of years later, Bava found employment on an adaptation of the tragic story of Beatrice Cenci, a film directed by Freda, helping out with optical effects. Somewhere along the line, the pair dreamt up the idea to make a horror movie. Freda would direct, of course, and Bava would shoot the picture – his pal’s ability to work fast was apparently part of Freda’s sales pitch. Ermanno Donati and Luigi Carpentieri, the producers, liked the scenario Freda had described to them (the idea was expanded upon by Piero Regno and J.V. Rhemo) and approached Goffredo Lombardo of Titanus. The project was given the go-ahead. British film critic and broadcaster Alan Jones noted that Mussolini’s banning of horror titles in previous years produced a potential opportunity in the market: ‘The fact that these famous classics were finally shown on Italian shores during the early 1950s might actually have been the impetus for Freda and Bava to consider delving into the much-maligned fantasy field in the first place’ (2013: 22).

I vampiri, much like Black Sunday four years later, differed from the traditional vampire picture. Vampirism, here, was depicted from a cod scientific angle and related to the theme of ageless beauty, eternal life and the sheer narcissistic anxiety of losing one’s looks. Stacey Abbot highlighted the film’s modernism in her online article for Kinoeye (2002): ‘In particular, I vampiri modernises the vampire legend by presenting vampirism as a product of the modern world rather than an opposition to it long before the presence of a vampire within a contemporary setting became the standard.’

The plot is delivered in the mystery-thriller style with interruptions of Gothic atmosphere. An intrepid and mightily determined reporter, Pierre Mantin (Dario Michaelis), is set on exposing the dastardly Giselle du Grandan (Gianna Maria Canale), who keeps her youthful looks intact via a serum whose main component is the blood of virgins (from girls who are captured and disposed of once they’ve been drained of their vital life source).

The crimes of Giselle du Grandan in I vampiri were based upon the legend of Elizabeth Bathory who, in 1610 (only twenty years before the initial events of Black Sunday), was arrested on suspicion not only of witchcraft, but the murder of hundreds of young maidens of the court and village peasants. Of course she did not soil her own well-manicured hands and murder anybody herself – she had willing lackeys to do the dirty work for her. Countess Dracula (as Hammer would one day call Bathory) believed, under guidance from a local witch, that bathing in blood would stop the ageing process. It didn’t. She ended up imprisoned in a castle for the rest of her natural life. Those who aided the crazed aristo were not so fortunate.

Italian Gothic is born in I vampiri

On Day 10 of the allotted 12-day production, Freda walked out. It was said to have been a tense set with the director’s attitude described as ‘imperious’ by Bava (Lucas, 2007:157). The cameraman and special effects magician stepped up to the plate and reworked the picture working against varying factors such as actor availability and budgetary constraints. Tim Lucas detailed the changes in a DVD commentary for Black Sunday:

Bava’s input was especially significant, as it was he who decided to raise the supporting character of the journalist to the lead, dispense with a Frankenstein sub-plot about a dismembered criminal reassembled and brought back to life, and flesh out the film with stock footage, montages of newspaper presses and audaciously sustained long-takes.

It would be pushing it to declare I vampiri as a neglected masterpiece, but it is a hugely underrated work and very cleverly sets out what a horror film with a modern edge and sensibility could achieve. The unusual angles, shadow play, the dolly shots, deep-focus photography and trick effects would all be found again in Black Sunday, although with much more ambition. I vampiri’s aesthetic is an amuse-bouche compared to the full visual feast served by the latter.

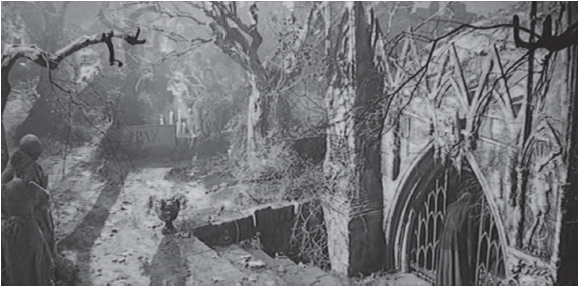

The narrative, quite importantly, does not take place in Italy but Paris, France. The perfume of glamour associated with the City of Lights ramped up the thematic subtext. Paris is the global fashion capital and one of the most quixotic cities in the world. Giselle du Grandan, the wicked vampire at the centre of the storm could reside nowhere else on earth but among the high society of Paris, the classy boulevards and famous fashion houses. Her chateau, however, is more like a Gothic castle than a typically posh Parisian residence. Bava shot all the Parisian street scenes in the courtyard of Scalera Film Studios.

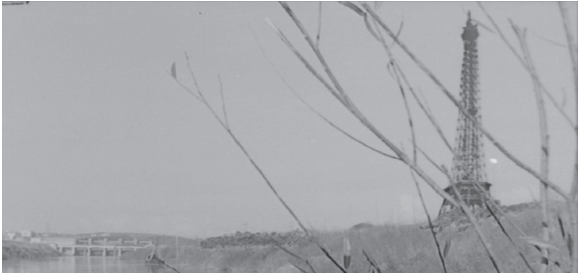

I vampiri showcased Bava’s inventiveness from the very beginning via a matte painting/shot of a distant but still giant Eiffel Tower, with the foreground given over to wasteland and a river. Given the semi-rural look, there’s no way this is a convincing portrayal of 1950s Paris in relation to the tower’s position. The graphical quality serves as an idiosyncratic interpretation of the city with a cultural landmark plonked down somewhere it could never conceivably viewed from.

A glass matte shot of the Eiffel Tower overlooking a semi-bucolic landscape in I vampiri.

The same occurs later, in another matte shot, where we see the Notre Dame cathedral on the skyline. The picture postcard opening credits sequence, set to Roman Vlad’s romantic, doom-laden score, helped in the establishment of a (creaky) foreignness that worked rather like the dreamy and weird paintings of Henri Rosseau (1844–1910). Presumably Bava and Freda hoped audiences wouldn’t recognise or care about the phoney use of locations. Yet I can’t help but think of the French artist in relation to Bava, here. Whether some wild jungle with a pouncing tiger (Rosseau) or the brooding, fog-smothered painted landscapes of Moldavia (Bava) or an Italian semi-industrial landscape something kindred and uncanny in the exotic visions of both artists.