Bava’s debut feature film is considered to be among the most stylish horror films ever made and won praise for its delicious look and cinematography. The mise-en-scène is ravishing – marrying fairy tale to surrealist irrationality – and special effects design, at times, ingenious. John Landis described Bava’s directorial skills with a crude American idiom: ‘Making chicken salad out of chicken shit’ (Landis, Operazione Paura).

Writing in 1981, Tom Milne summed up Bava’s film (noting all its release titles) as: ‘A chillingly beautiful and brutal horror film’ and ‘atmospherically the film is superb, a chiaroscuro symphony of dank crypts and swirling fog-grounds’ (1981: 235).

Producer Nello Santi initially wished to shoot in Technicolor. Sticking to his guns, Bava filmed on monochrome stock and delivered what is touted as the last great black-and-white Gothic horror picture. An American producer named Lawrence Woolner actually approached Bava in the late 1960s with the proposal to remake a colour version of Black Sunday. The project never came to pass although the director is said to have entertained the idea.

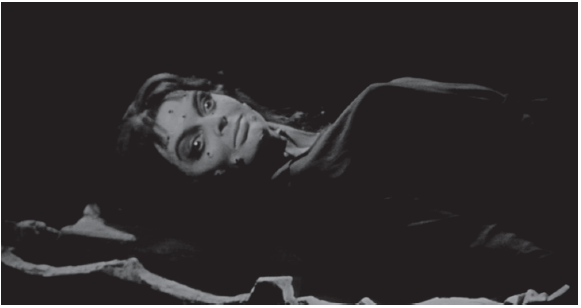

Katia’s introduction is one of the most gorgeous dolly shots in the film

The simple fact of the matter is the film would not have worked so well if shot, printed and exhibited in colour. The clever effects and use of miniatures, matte paintings, grotesque character transformations and the painted backdrops would have been laid bare. In black-and-white, these elements fused together to create a magical air. The film’s clear artifice married to the Gothic tone and fairy tale sensibility lend Black Sunday the greatest visual power. If it had mimicked the palette of Hammer, say, the magic and atmospherics would have been irrevocably lost. The black-and-white photography is utterly spellbinding, in places. Take, for example, the scene in which the Innkeeper’s daughter goes to milk the cow … how the mood can change so suddenly: the soft welcoming light of the inn fades away (along with the voices of raucous patrons getting steamed on vodka) and deep tenebrous shadows take over. Space becomes tight and the world is suddenly loaded with menace. Although Sonya is mere yards away from the inn, a creepy ambience takes control and the whole time the low angle dolly shot has focused on the young girl’s hesitant face as the space closes in around her. The framing is masterful.

Shot on 35mm, using a 1.66:1 aspect ratio, Bava storyboarded his debut feature (a move Tim Lucas noted was unusual for the time) and is credited with photographing the picture. The decision to pre-visualise the film, even if the script was in a continual state of flux, showcased how strongly Bava favoured imagery over the concerns of telling a story, let alone constructing the machinations of the plot. Ubaldo Terzano served as camera operator but it is also said he lighted the picture and the film’s look was achieved through collaboration between director and assistant. Bava stated his debut was ‘Filmed entirely with a dolly because of time and money, the photography in a horror film is 70 percent of its effectiveness; it creates all the atmosphere’ (Jones, 2005: 62). He also claimed that it would take all of seven minutes to light a shot and twelve minutes to light an entire room.

Shot on soundstages to allow the director full advantage and control of the elements, outdoor scenes were shot on location outside Rome at a castle in the village of Arsoli, which featured as the Vajda home and around Mirgorod.

Ennio De Concini, Mario Bava, Mario Serandrei (the film’s editor) and Marcello Coscia all contributed to the story. The Mask of Satan and AIP versions listed De Concini and Serandrei as ‘Screenplay By’. The editor of the film was no writer but helped Bava shape the film in post-production, so much so, that he earned recognition.

The shooting and editing process is vitally important to understanding how Bava ultimately crafted his picture after shooting. It reveals what could be described as an experimental approach and method which recognised his artistic manner even if the end result was far from perfect. He allowed himself the freedom to alter and rearrange entire scenes and plot chronology. It didn’t always work out as scene placement can feel very odd, including the brief moment when Katia appears ever-so-shady in her intent and dialogue – professing that a young girl’s eyewitness account of seeing a resurrected Javuto driving a phantom carriage is poppycock. The girl recognises the portrait in the Vajda castle. ‘It’s only the imagination of a child. Why this man has been buried for over two centuries. Please stop all this will you or I’ll go mad.’

It is an unusual and off-key scene. It has been suggested by Tim Lucas that Bava intended Katia and Asa – at some point in the story previously – to have switched places and this sudden plea for calm and common sense is really a distraction to throw Gorobec and others off the scent. There’s something about her smile at the end of the scene, as Constantine asks the good doctor to stay the night at the castle (before the scene cuts away to an exterior locale: a chapel turned mortuary). The line, ‘Yes, please do, we’d all feel so much safer’ rings most odd. Clearly, any idea of a switcheroo was abandoned but the jarring scene remained in the final cut. It should be pointed out that Katia is wearing her crucifix under the blouse, which Asa would not be able to stand for a second. So maybe she really is appealing for everybody to be rational in the face of the supernatural? Yet her sudden forthrightness contrasts too much against what we can call her melancholic disposition that is suspicious. Imagine Gorobec all of a sudden gaining a semblance of personality beyond his perfunctory role as the hero? (It would be noticeable.) Katia’s stance is a last ditch attempt at common sense and reasoning because if it’s all true – as indeed it is – then she will potentially suffer a fate worse than death. She is the archetypal Gothic female figure.

Lamberto Bava, the director’s son and also a film-maker, once explained how his father worked in shaping his movies during their actual production or later in the editing room. Improvisation and changes occurred all the time, but it looks very much like he altered quite a lot. Tim Lucas recounted Lamberto Bava’s anecdote of how his dad worked in the audio commentary track for Black Sunday: ‘My father was never satisfied by his stories and he continued to revise them, even after shooting had begun, changing as much as 50 to 60 percent of the script.’ This comment, explaining how his father’s worked was backed up by leading lady Steele. ‘I never saw a script for Black Sunday. We were given pages day to day. We had hardly any idea what was going down. We had no idea of the end or the beginning either. I’m sure that Bava knew. Maybe he didn’t’ (Lucas, 2007: 297).

TECHNIQUE: CLOSE-UPS AND CRASH ZOOMS

The close-up is one of cinema’s most unique and powerful tools. A close-up can provide an intense intimacy and detail, and often in horror movies, a sudden electric shock. If Renée Jeanne Falconetti’s tears-stained face represented goodness and sacrifice in Dreyer’s The Passion of Joan of Arc (1928), Steele’s role of Asa is the flipside of that – the great sinner whose allure is positively wicked and documented often in close-up. Both Dreyer and Bava fetishised the close-up in their films.

As well as providing shots of Asa’s mesmerising fatal beauty, the close-up is deployed to ramp up moments of violence and terror that break away suddenly from the Gothic elegance and replaced with a more modern and daring representation of violence against the flesh. The scene in which Asa and Constantine rush into their father’s room to find him stone dead in medium long shot whips a full 180 degrees into a close-up of Prince Vajda’s mauled dead face. The suddenness of the camera movement and change of spatial perspective – a real feat of lightning quickness from the camera operator on a customised 35mm camera modified by Eugenio Bava – is one of the film’s most frantic and surprising moments. So well applied was the close-up, in particular, that both AIP and the BBFC had grave reservations and issues. It made scenes simply too gory. Prince Vajda’s immolation in the fireplace was cut heavily by AIP and Kruvajan’s death removed entirely.

Kim Newman, in his autobiographical essay on video nasties, ‘Journal of the Plague Years’, commented very succinctly on why Italian horror films are so damn effective. ‘Italian films are staged slowly and with ritual care’ and he goes onto say, ‘It is perhaps these meticulous, grand-standing displays of bodily abuse that so upset’ (1996: 141).

There can be no arguing that the stylised violence in Black Sunday can nasty. Writer Kier-La Janisse pointed out: ‘Bava’s movies were not known for their kind treatment of women as much as the fetishisation of violence directed at them’ (Jannise, 2012: 112). This is totally true: the close-up erotises and fetishes Barbara Steele’s face in relation to pain and suffering as well as in other scenes, where her deathly beauty enchants.

The Mask of Satan, pounded onto Asa’s face by a muscle-ripped lug with a massive hammer, is a startling moment (even if AIP chose a quick fade to black at the moment of impact which removed the sight of bloody tears streaming down the mask’s cheeks, a gruesomely poetic touch). The choice of shot, camera angle and sound design combined to potent effect to produce a wince, as we imagine the thick spikes smashing through bone and soft tissue. Of course, it was hardly the first moment horror movies had ever produced such a violent or repulsive image, but had anybody dared open their film in such a spectacularly gruesome fashion? Imagine, if you will, the scene in Hammer’s Dracula, where upon Van Helsing smashes the stake into Lucy’s chest as she lays in her coffin, opening the film rather than occurring towards the end of the second act!

In a video interview included on the Arrow Video Blu-ray release of Black Sunday, recorded in Italian, Steele was still impressed by that scene’s impact and her part in one of the most sadistic sequences in horror cinema history. ‘The first five minutes of Black Sunday were incredibly powerful, you know. I’m burned, denounced, there were big men, these executioners all dressed in black, who put on me this mask with these … what are they called … these big thorns in my face. It was an extremely powerful scene in terms of atmosphere … all this before the opening credits.’

In Black Sunday – though more in La maschera del demonio and The Mask of Satan cut – when spikes hit human flesh blood will spurt wildly all over the place. When a red hot brand marks human flesh, it will bubble and sizzle and leave a lasting mark. Even if softened by editing and discreet fade-to-blacks by AIP, the violence still packs a punch by the sheer insidiousness of how it is presented (photographically, the choice of shots, etc.). AIP deemed certain images and shots permissible (Katia finding Ivan hanging from a noose). Others, not so much.

During the opening sequence, one of the most amusingly grim flourishes Black Sunday proffered is the mask held up by the executioner as he walks towards the camera (thus the viewer). The spikes loom ever large. They get closer and closer until the camera – thanks to some nifty editing – looks as if it passes through the eye of the mask and out the other side. For a brief moment, Bava has forced a pseudo-subjective viewpoint onto the spectator. Suddenly our somewhat distant voyeurism is interrupted and takes on an unwanted, more direct, claustrophobic and suffocating gaze.

The crash zoom technique and Italian genre cinema in general go hand in glove. Bava, especially, employed it a lot throughout his career – to the point where it approached that hoary old critical accusation ‘self-parody’. Yet in Black Sunday, the crash zoom served to heighten the sense of fear and formed a metaphysical symbolism. Like the close-ups, the in-camera effect allowed Bava to express the supernatural and dark magic abilities of Asa and Javuto as they entered or prowled on the edge of a scene. As the camera’s focus ‘crashes’ into an object the detail becomes larger. So if it’s a menacing figure, such as the villains in the movie, the dread is increased. Several instances of the zoom effect are used in relation to Asa’s awakening, too: often fixed and slowly creeping towards her tomb. When the priest and Gorobec open the coffin in the cemetery, Kruvajan’s sleeping face looks unlike the avuncular chap we are first introduced to in the opening scenes. His degradation is complete and the crash zoom is used to register Gorobec’s saddened spirit, revulsion and disbelief at the fate of his old friend. When the children find the corpse of Boris by the river’s edge, Bava again used the crash zoom to heighten the horror and tension, the man’s face caked in mud and blood.

The scene in which Javuto attempts an attack on Prince Vajda strings together a sequence of crash zoom shots in bravura and frenzied succession – some moving forward and some in reverse – so that reaction shots work as a form of dual between the powers of Good and Evil. The mightiest comes as Prince Vajda repels Javuto by brandishing the crucifix. Demon be gone!

Mario and his father Eugenio were indisputably maestros when it came to visual effects. Bava Jr. used food stuffs – rice, jelly and poached eggs – to make the blood chill. The film is packed with in-camera practical effects, glass matte paintings, miniatures, split screen, clever shot transitions and dissolves, shadow play to suggest off-camera action. To simulate travel and movement, as Kruvajan and Gorobec travel in their carriage, Bava had crew members hold branches and walk them by the window. It’s these simple solutions as well as more technically complex designs which so impress film-makers and fans. Bava (and his father) knew their craft inside out.

The chief inspiration for the film’s transformation scenes, which suggested life force being drained away, in both I vampiri and Black Sunday, can be seen in the 1925 version of Ben-Hur (dir: Fred Niblo) and Rouben Mamoulian’s Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1932).

Red grease pencil, invisible on the black and white film stock, and then lit with a red light that concealed the make-up. As the transformation began, the red light was slowly replaced by a green light, giving the appearance of sudden ageing as the makeup gradually becomes visible. Bava enhanced the effect by fitting the actress with a wig made of artificial filaments that photographed white when exposed to direct light. (Lucas, Black Sunday audio commentary)

Asa’s life force is drained from her body as the flames rise

BEHOLD THE MASK OF SATAN!

Eugenio Bava worked on his son’s picture seemingly without ever setting foot on the set. He not only helped customise cameras for the shoot, he sculpted and cast the iconic mask (one was made in bronze) inspired by Gogol’s reference to an ‘iron face’ in Viy, as well as other – cheaper – versions of the mask. The finished result appeared suitably medieval but very much unlike the description used by the Ukrainian writer. He also fashioned the ‘dead skin masks’ of Asa, Kruvajan and Javuto from latex foam.

The Mask of Satan plays a vital function regarding the film’s mythology. Masks have been linked directly throughout history with supernatural beliefs, to ward off evil spirits. Is the Mask of Satan a form of death mask too? It is not lifelike, of course, but does it not show the monstrous form under the skin?

‘The true face, the face of Satan,’ Kruvajan tells young Gorobec.

The very first appearance of the mask occurs in long shot as the executioner moves towards Asa with the intention of branding her with the ‘S’ brand of Satan. We see the mask closer, in side profile, half obscured by shadowy darkness. The cutting and choice of shots is teasing. The giant nose, too, looks very much like an axe embedded straight down the centre of the face. Even these glimpses offer a ghoulish portent.

The Mask of Satan designed by Eugenio Bava

The mask performs several important narrative tasks. The rictus grin, prongs that could well be vampire fangs as well as tusks, bushy eyebrows, flared nostrils and streamlined nose – it runs from an apex at the top of the mask’s head straight down the centre of the face to the mouth – make it look carnivalesque and treading a fine line between the comic and the insidious. He should be feared but also mocked as the weaker authority to God. The mask is the essential comic-grotesque depiction of Satan. The designer of the mask, within the world of Black Sunday, focused on the bestial and the facial structure brings to mind the goat-like Pan.

Griabe orders his minions: ‘Cover her face with the Mask of Satan.’ We then cut to another medium shot of a mask lying at the foot of a tree. This is our first real look at the thing, and in much better light. ‘Nail it down!’ commands the Inquisitor.

The mask, as well as functioning as a cruel and unusual torture device, also plays a deeply misogynistic role. Prince Vajda has not only ordered his sister to ‘death by immolation’ – which doesn’t make much sense if she’s going to reside in hell anyway and is already, as a vampire, technically dead – but he wants to destroy and deny the woman her own face and substitute it with the mask.

Beyond its use as an instrument of torture and wrecker of beauty, the mask is a supernatural talisman imbued with abilities to ward off evil. Asa, having failed to be burned at the stake due to a thunderstorm and rain lashing down at the exact moment of her death – ‘I beheld Satan as lightning fall from heaven’ (Luke, 10: 18) – is placed in the family crypt. They design the tomb with a sheet of glass so that she can symbolically see the mask’s reflection for all eternity. Also, as Kruvajan explains to Gorobec: ‘They feared that the witch might try to rise again and placed a cross visible to her to stop that happening.’

FEMALE HORROR ICONS

Female horror icons were few and far between before Barbara Steele’s portrayal of Princess Asa. There were plenty of damsel-in-distress roles (Fay Wray in King Kong, 1933), but the closest we get, arguably, is Elsa Lanchester’s Bride in The Bride of Frankenstein. Regarding the latter, yes, the movie title is exclusively devoted to her and the tagline boasted ‘The monster demands a mate!’, and Graham Greene’s 1935 review for The Spectator commented on her ‘strange electric beauty’ (1935: 6), but the character’s actual screen-time is nothing more than a few minutes leading to the film’s explosive and symbolic climax (a phallic-shaped tower is obliterated). With her deliciously camp Nefititi hairdo, balletic movement and svelte patchwork body, the Bride is instantly recognisable but rather jilted by expectation and actually more the bridesmaid to her own film rather than the true focal point, which was still that lumbering and now horny oaf, played by Karloff.

The Island of Lost Souls’ Lota the Panther Lady could be another candidate but, again, the film is just not as widely known outside cult cinema confines. Gloria Holden in Dracula’s Daughter (1936), with her Sapphic longings, is a possibility, but who can truly remember the character … or the film? Could we edge a bet on The Wicked Witch of the West in The Wizard of Oz (1939)? Maybe, but it’s not a horror film (despite the BBFC’s ‘A’ for ‘Adults Only’ rating given upon release in 1939). And whilst Hammer’s Valerie Gaunt, in the 1958 Dracula, showed us the first depiction of a female vampire flashing her pearly white gnashers, the character – although a deeply erotic figure – is nameless and killed off so swiftly as to make hardly any impression at all. None – bar Lanchester – could seriously stake a claim until Steele came along.

ASA

How do you solve a problem like Asa? The answer is: tie the girl to a wooden rack, scar her back with the Brand of Satan, follow that bit of sadism by making her wear the Mask of Satan and then set the body on fire so she may be purified of Lucifer’s evil influence by God’s righteous fiery element. If only it were that simple…

Asa is a cinematic depiction of a figure often found in Gothic literature and art history known as the Fatal Woman. As Mario Praz stated in The Romantic Agony, with an annoyed air of stating the obvious: ‘There have always existed Fatal Women both in mythology and literature, since mythology and literature are reflections of various aspects of real life’ (1933: 189).

When Kruvajan is taken to meet Asa in the crypt, her speech, a sales pitch if you will, attempts to convince the doctor there is beauty in death. ‘You will die but I can bring you pleasures mortals cannot know.’ Not that he has much of a choice. Yet he succumbs, almost willingly.

Fatal beauty: the deathly, voluptuous menace of Asa the witch’

Death and Beauty were ‘looked upon as sisters by the Romantics’ and ‘became fused as a two-faced herm, filled with corruption and melancholy and fatal in its beauty – a beauty which, the more bitter the taste, the more abundant the enjoyment’ (ibid: 30).

Percy Bysshe Shelley’s poetic recounting of seeing a painting of the famed Gorgon in the Uffizi Gallery, Florence, has been described by art historian Praz as a ‘near manifesto’ for the Romantic concept of Fatal Beauty and of the femme fatale which so fascinated the artists, poets and writers of the time. Asa might well be ‘La Belle Dame sans merci’ who ‘hath thee in thrall’ of John Keats’ famed poem.

Praz, too, felt that no other art movement in history had so explored the complexities of Beauty and Death as the Romantics. Shelley would describe the effect of the painting as the ‘tempestuous loveliness of terror’ and ‘Its horror and its beauty are divine.’ The former could well be assigned as the perfect description of horror cinema’s allure and effect. And although Asa is never depicted with wriggling asps in place of locks of hair (Lamberto Bava’s ‘remake’ of La maschera del demonio did make such a reference), she still makes a fine spiritual twisted sister of the Medusa. They are cut from the same cloth. Poor Kruvajan was doomed the moment he entered the crypt!

However, for all its initial radical set-up – a movie about a witch who is dominant, sexy, deadly, and in complete control of male characters and events right up to the finale – when things come a cropper, Black Sunday is not a stake in the ground for female empowerment and neither is it forward-thinking enough to let her win. Bava’s depiction of the female characters is strictly within the classical confines of art history traditions (Romantic and Gothic) and imbued with the rather dull Catholic and conservative representation of the women in that hoary old ‘Saint and Whore’ dualism. Asa and Katia can be read, too, as Stoker’s Lucy Westenra before and after she’s turned into a vampire. Katia is the sweet, pure and unthreatening male ideal of woman – completely and utterly spellbinding in her attractiveness and manners – and Asa is the other side of the coin. ‘The sweetness was turned to adamantine, heartless cruelty, the purity of voluptuous wantonness’ (Stoker, 1897: 175).

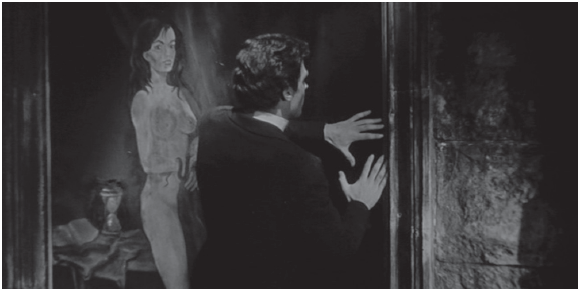

Two portraits, seen in the film, offer this two-sided depiction of Asa. In the main hall of the Vajda castle, we see her as a young lady of the court and in a secret chamber discovered by Gorobec and Constantine, she is depicted naked and surrounded by satanic objects.

We know next to nothing about Asa. The film begins at the moment of her execution. Given the Moldavian setting and that the character is most definitely wise to the ways of witchcraft, perhaps she attended Scholomance, the legendary private school of the dark arts hidden away somewhere in the mountains of Transylvania?

Asa’s punishment might have also been for the transgressing against patriarchal dominance. Did she turn away from her duties and responsibilities as a young lady of the court and grow sexually ‘deviant’ and against God? Yet the symbolic two fingers up to her father and the other Father is hardly transgressive when seeking an alternate father figure, in Satan. ‘He may promise freedom but he is the figure of bondage’ (Nugent, 1983: 10).

Bondage, funnily enough, is the operative word. The very first shot of comely Asa is downright kinky. She is trussed up in ropes, her slender milk-white back revealed by a torn gown with her exquisite legs showing off a fine figure. Let us admire her fine form like that of an ancient statue in a museum or an adult magazine for ‘niche’ tastes. The effect is the same, either/or. In not showing her face immediately, the camera forces attention directly on the glimpses of flesh and the shape of the body in torn rags. See how the light bathes her right calf and slender shoulder in a soft glow, her abundant black hair flows down the back and slender arms held high. She is ‘on show’. The camera closes in and she is revealed as a gorgeous young woman who looks simultaneously in pain and more than a bit pissed off with how things have gone down. The hooded brethren around Asa and the burly executioners – whose faces are obscured fully by hoods – are figures of male power and they look on unmoved.

PORTRAITS OF A LADY OCCULTIST

As mentioned, there are two portraits of Asa seen in the film. Both are unusual, but represent in visual form the tradition of women as either saints or whores. The first portrait we see hangs in the dining hall of the Vajda castle.

Asa stands in side profile. The background is given to a landscape of rolling hills. She wears a long gown, her arms are folded and the expression on the face, while typically demure, is uneasy. She looks like a bored aristocrat. The likeness to Steele is very apparent, too, and more so than the second painting.

Asa’s portrait hangs in the Vajda castle living room

The other portrait of Asa is seen in the third act. It is a much rougher piece of work with Asa looking almost feral, and she is stark naked. She holds in her hands a crystal ball and an asp and is surrounded by great big leather-bound books and parchments. It is a very unusual portrait of a lady but also establishes her attitude to the conventions of social standing as well highlighting her demonic beliefs. The brazenness of this image is remarkable and it offers extra clues regarding Asa’s life and religious practice.

The secret portrait discovered by Gorobec leads to the Vajda crypt

KATIA

If a fairy tale has a wicked witch then there must be a princess. The theme of demonic possession is strong in Black Sunday. It might have been ignored somewhat because everybody is still debating whether the villains are vampires or not. Asa wishes to take over the mind and body of Katia and to effectively transfer her soul and personality into the poor girl. Bava’s decision to present Asa and Katia as visually indistinguishable – even their hairdos look the same – makes the theme of demonic possession richer, more irrational and nightmarish. Asa is already within Katia – her face is the face of Katia – and has informed her entire haunted life and understanding of the world. Taking over the body is the icing on the cake. Given the explicitly supernatural context of the plot, Katia’s looks are not the result of a fine aristocratic lineage.

Constantine reminds his sister how the painting of Asa has been ‘enthralled by that strange old painting’ since childhood. Katia replies: ‘It holds danger for me … something alive about it; something mysterious about the eyes. That’s it! They’re vultures’ eyes, somehow.’ Is it not particularly horrid to give this portrait such a prominent place in the Vajda house given its effect on poor Katia?

There is, too, another character in Black Sunday referred to as Princess Macha, who was ‘mysteriously murdered’, Prince Vajda claims, and is the same age as Katia. She, too, looked exactly like Asa. Prince Vajda quite rightly fears for his daughter’s life. Katia is not the sweet and demure princess of tradition. She is essentially as tragic a figure as Asa, a woman living under the strict rule of a patriarchal society. She might well agree with Asa that it sucks being a lady of court in such a restrictive world. She is seen as a precious jewel by Prince Vajda, the father, and a potential love interest and wife material by Gorobec. Can’t she be her own woman? Black Sunday cheated Katia of a scene in which she reflects on her life and fate. Gorobec notices Asa walking in the garden near the fountain. In The Mask of Satan we get a whole exchange between the pair which is absent from Black Sunday – as if the shot of Katia glumly staring into the fountain was enough when it really comes across as abrupt and unfocused. The scene starts with a panning shot from the trees to Asa standing by the fountain as Nicolosi’s refrain – what can be called ‘Katia’s theme’ – plays out. ‘What is my life? It is sadness and grief; something that destroys itself day by day and no one can rebuild it,’ she tells Gorobec.

WHO IS JAVUTO?

Who is Javuto exactly? In AIP’s version of the film, he is described by Griabe as Asa’s ‘serf’ before adding ‘who you forced to do your bidding!’ We might well say he’s a first-class doofus besotted with Asa and like Edward G. Robinson’s Chris Cross in Scarlet Street (1945). Many a foolish man in the movies/history/literature was ruined by loving somebody unobtainable. (Asa is the archetypal femme fatale, don’t forget.) She is therefore directly responsible for his death and we can feel pity for him. The dialogue is seemingly straightforward enough regarding the character, but something isn’t quite right…

Javuto is dressed like a nobleman rather than some scuzzy peasant helper. The portrait in the Vajda castle, too, hangs pride of place next to the fireplace. His clothes bear a dragon emblem thus heavily suggesting he is a member of the Vajda family. Were the pair ‘kissing cousins’ or even more closely related? Is Javuto really Asa’s brother and were the pair involved in a dangerous incestuous liaison that, once found out, along with all their interests in Satanism, vampires, whatever, condemned them to premature deaths at the hands of the Inquisition, conveniently led by their brother, Griabe? The original Italian credit for the character revealed just that: ‘Prince Ygor Javutich – fratello della stregia’, meaning, ‘brother of the witch’. (In Croatia, vampires were known as ‘pijavica’ and incest given as a cause of the transformation.) Given the secretive nature of their passion, is Javuto also responsible for that rather saucy, if unflattering, portrait of Asa?

WITCH OR VAMPIRE?

It has been noted since the film’s release that Black Sunday appeared very much to confuse the terms ‘witch’ and ‘vampire’. In fact, Black Sunday is entirely within the ever-changing and malleable vampire figure and the witch and keeps within the bounds of the concept laid out by Gogol’s short story. The terms ‘vampire’ and ‘witch’ are linked throughout mythology and folklore: whether it’s an etymological root or folkloric narratives that cross pollinated them. They are creatures bound by blood. The Russian form of the vampire - the ‘eretica’ – was a woman who had ‘during life offered her soul to Satan in return for magical powers’ (Barlett & Idriceanu, 2005: 119). Alas, the ‘eretica’ is only active during spring and autumn, which puts the kibosh on Asa living for one hundred years on Katia’s blood. The Mask of Satan does, however, take place on the Feast of St. George, placing that film’s narrative right in the springtime.

Of course, none of this is an excuse for the plain inconsistencies present in Black Sunday in general. The narration during the opening sequence (AIP and The Mask of Satan cuts) mentions both witches and vampires, but the dialogue exchanges between Asa and Griabe do not make any reference to either vampires or vampirism. Only Voiceover Man puts the idea into our heads. Asa is convicted of being a vampire and yet she’s clearly alive and doesn’t appear to boast any of the mad skills Count Dracula has at his disposal (shape-shifting, etc.). The princess is to be given a witch’s death, by immolation, after the Mask of Satan has been hammered down onto her face. One can understand very well any confusion felt by the viewer. Yet, as Hall Baltimore (Val Kilmer) asked out loud in Francis Ford Coppola’s Twixt (2011): ‘What is a vampire but a witch that sucks blood?’

Black Sunday begins with this introduction:

One day in each century it is said that Satan walks amongst us. To the God-fearing, this day is known as ‘Black Sunday’. In the 17th century the Devil appeared amidst the people of Moldavia. Those who served him were monstrous beings that thirsted for human blood. History has given these slaves of Satan the name ‘vampire’. Whenever they were caught they were put to horrible deaths. Princess of Asa of the aristocratic Vajda family was one of these. She was sentenced to a witch’s death by her own brother.

The Mask of Satan begins:

In the 17th century, Satan was abroad on the Earth and great was the wrath against those monstrous beings, thirsty for human blood, to whom tradition has given the name ‘vampires’. No appeal for pity or mercy was awarded. Family members did not hesitate to accuse brothers, and fathers accused sons, in the frantic attempt to purify the earth of that horrible race of blood thirsty devouring assassins.

When summing up her crimes, Griabe exclaims:

Asa, daughter of the House of Vajda, this court of the Inquisition of Moldavia, has found you guilty. I, as the second born of the princes of Vajda – and as Grand Inquisitor – hereby condemn you. And as your brother, renounce you forever, severing the ties that bind us. This inquisition finds you not only guilty as a servant to Satan, but a high priestess to him!

The Mask of Satan runs:

Asa, daughter of the House of Vajda, this high court of the Inquisition has declared you guilty. I, the second born son of Prince Vajda, as Grand Inquisitor, do condemn you. As your brother, I repudiate you. Too many evil deeds have you done to satisfy your monstrous love for that serf of the devil, Igor Javutich. May God have pity on your soul, in this your final hour.

It could be deemed highly strange and disappointing to set such a scene, explicitly suggesting vampires will be involved, and then refusing to give viewers the staples of the genre. And yet Bram Stoker’s novel sees the evil Count packed off to hell without the traditional stake through the heart. He’s stabbed by Quincey Morris’ bowie knife and then beheaded. In Black Sunday, the crucifix is used as a tool in warding off evil. Prince Vajda’s cross annoys Kruvajan during the scene in which he pretends to attend to the stricken old aristocrat. He informs Constantine and Katia to put the thing away on the pretext it might upset the old man: ‘Take it away, it’ll irritate him.’ Later on, Prince Vajda and Boris the servant bear the familiar fang marks which suggest the sucking of blood.

It is documented that Bava had his leading lady and her co-star wear plastic fangs (there’s an extant production still of Dominici showing off the incisors) but changed his mind. There are two stories as to why he removed them. One is that Bava, ultimately, didn’t like the way they appeared on camera and stated: ‘I made the actors get rid of them because they were becoming a cliché even then’ (Lucas, 2007: 297). The other story version goes that Steele refused to wear them because they looked daft. Bava also claimed ignorance of vampire folklore and mythology:

The strange thing is that I didn’t know, before making this film, what vampires were. In our country, we have no vampires. As a child, I heard our maid tell us fables about Sardinian and Sicilian bandits, which terrified me, but I never heard of a vampire. In our country, the sun drives such things away. (ibid.)

It isn’t quite right to claim as Matt Bailey does, in his essay on Black Sunday (Arrow Video booklet), that Bava created his own uncanny mythology. Betwixt wishing to avoid cliché and feigning ignorance, the film managed to align itself to the fog of folklore.

THE SATANIC LORD

Universal Pictures’ success in 1931 with their adaptation of the stage play Dracula (adapted by Hamilton Deane then revised by John L. Balderston for the acclaimed Broadway run) and the movie sequels, proved immensely popular with audiences and continued the appreciation and fascination with the ‘Satanic Lord’ version of the vampire. Odell and Le Blanc noted that: ‘The success and influence of Browning’s Dracula is so immense that is can be difficult to view with real objectivity’ (2008: 27).

In something of a key scene, Van Helsing (Edward Van Sloan) detailed the mythology widely adapted by subsequent movies. ‘A vampire casts no reflection in the glass. That is why Dracula smashed the mirror.’ Later, he tells Dr. Seward and a worried John Harker: ‘A vampire, Mr. Harker, is a being that lives after its death by drinking the blood of the living. It must have blood or it dies. Its powers only last from sunset to sunrise. During the hours of the day it must rest in the earth in which it was buried.’

Count Dracula and other vampire figures, as with the most popular literary incarnation, found popularity as sleek and seductive individuals that slept in coffins in dank crypts, and mesmerised victims, often young ladies. That Black Sunday dispensed or altered these elements somewhat doesn’t make it problematic or the film inauthentic. Bava managed to dig into a mélange of 17th century cases of vampirism and the Romantic/Gothic figure that arose from John Polidori’s short story, The Vampyre (1819). Here we have what Leonard Wolf called (cited in Legends of Blood, 2005) the ‘prototype vampire’ who was a ‘nobleman, aloof, brilliant, chilling, fascinating to women, and coolly evil’ (2005: 32).

The doomed physician/author modeled his Lord Ruthven character on Lord Byron, a former patient and man long suspected of a Javuto-like affection for his sister. In the 1920s Montague Summers (1880–1948), an author and man of the cloth who believed unequivocally in the world of the supernatural, authored two books titled Vampires, His Kith and Kin (1928) and The Vampire in Europe (1929). Summers noted (cited in Legend of Blood): ‘throughout the shadowy world of ghosts and demons there is no figure so terrible, no figure so dreaded and abhorred, yet dight with such fascination, as the vampire, who is himself neither ghost or demon, but who partakes the dark natures and possesses the mysterious and terrible qualities of both’ (2005: 7).

As we can deduce from that quote, far from clearing up the matter at hand, he ‘succeeded in only in showing how difficult it is to define the characteristics that exclusively belonged to the vampire,’ according to Christopher Frayling (1991: 5). We might well take the voiceover narration of Black Sunday as getting its genres confused, but some reports written in the wake of the notorious Arnold Paole case concluded that what was happening was ‘the work of Satan’ and ‘the vampire was Satan’ (ibid: 45).

A Romanian variation of the vampire is the Strigoi, a word whose origin has been disputed. The etymological root of the word is said to be from the old Italian for ‘witchcraft’ – stregheria. Psychoanalyst Ernest Jones’ On the Nightmare (1931), explored vampirism from a Freudian perspective and the notion of ‘haemosexuality’:

The word ‘Vampire’ itself, introduced into general European use towards the end of the first third of the eighteenth century, is a Southern Slav word. Its derivation has been much disputed, but the great authority, Miklosch, considers the most likely one to be the North Turkish uber, a witch. (ibid: 414)

The first cinematic vampires were not the kind we now associate with the term at all. ‘Vamps’ were proto femme fatales and would later resurface in film noir and gangster pictures. Early screen incarnations included Musidora as Irma Vep (an anagram of ‘vampire’) in Louis Feuillade’s serial, Les Vampires (1915), or Hollywood superstar, Theda Bara (a name the PR team announced was an anagram of Arab Death, for extra exotic allure).

In essence, there are four archetypal vampires in nineteenth-century fiction: the Satanic Lord (Polidori and others), the Fatal Woman (Tieck, Hoffmann, Gautier, Baudelaire, Swinburne and Le Fanu), the Unseen Force (O’Brien and de Maupassant) and the Folkloric Vampire (Merimee, Gogol, Tolstoy, Turgenev, Linton and Burton). (ibid: 62)

The movies jumped on the Satanic Lord and Fatal Woman variations proving that sex plays a huge part in their appeal, whether that’s Count Dracula, a babe from a Jean Rollin skin flick or Edward Cullen from The Twilight Saga. Black Sunday presented a heady mixture of three vampire types found in 19th century literature: the Folkloric, the Fatal Woman and the Satanic Lord.

The Folkloric aspect of Black Sunday occurred via the Moldavian setting, use of Nikolai Gogol’s source material, the time period between 1630-1830, and the unusual methods in which Asa, Javuto, Kruvajan and Prince Vajda are killed off in the third act. Black Sunday does not concern itself too much with commoners (or their superstitions) bar the ending and peripheral figures such as the Innkeeper, her daughter or the drunken coach driver. The narrative is set within a decayed aristocratic milieu far removed from the sophisticated worlds of Paris and London. Voltaire found the whole idea of vampires laughable and pointed out in a supplement to his Dictionaire Philosophique: ‘What! Vampires in our Eighteenth Century? Yes … in Poland, Hungary, Silesia, Moravia, Austria and Lorraine – there is no talk of vampires in London, or even Paris’ (1991: 30).

‘Our ways are not your ways,’ Count Dracula tells Jonathan Harker. Eastern Europe was the spiritual-political battle ground between Catholicism and the Orthodox Church: the place still part of Europe and yet outside the sphere of overt western influence. Mystery and exoticism arose along with a sense of the unknowable and wild things. ‘Transylvania’ translates in Romanian to ‘the land beyond the forest’. It’s the perfect place for monsters to thrive.

Although the aristocratic vampire incarnation fed off the plebs – literally – he doesn’t have a particular rapport with them or see them as anything other than victims in life or death, or hired help. The Archbishop of Trani, Giuseppe Davanzanti commented during the vampire scare/craze: ‘Why is this demon so partial to base-born plebians?’ (ibid: 30). Exactly because it reflected a culture and tradition in which aristocrats – alive or undead – believed they were above the law and could act with impunity! It’s the Marxist class system become Darwinian food chain.

Black Sunday fits in neatly enough to the folkloric vampire figure – from accounts written in the 17th and 18th century – as they were known to return to the family and attack their relatives. In the cases of Guire Grando and Peter Plogojowitz, both were said to have attacked their relatives and acquaintances.

Learned men of Europe – in a post-Enlightenment age – were baffled by the fad for vampires and horror stories coming out of the darkest corners of the continent. More than a few philosophers, religious clerics and scientifically-minded writers suspected local priests to be drumming up fear as part of a power play. The actions of Asa and Javuto are not the same as Count Dracula (novel) or Hammer’s version of the character. Theirs is exclusively a plot involving resurrection, secrecy and vengeance. It is never stated what Asa’s aims are beyond killing her ancestors even though Javuto states, ‘Through her blood your destiny will be fulfilled’ and ‘For the next hundred years her blood will keep you living.’ Perhaps the height of Asa’s plot is to keep on keeping on in the evil department and be immortal once again… rather modest enough aims for the undead, no?