This chapter will explore how the philosophers Socrates and Plato came to criticize Athenian democracy within a broader understanding of the aims of human life and the ideal place of politics in achieving them. To do so, we may begin building on the constitutional arrangements of Athenian democracy that were outlined in the last chapter, in order to ask: what were the aims, the values and the goals that the Athenian democrats used their powers to pursue? These were primarily survival, wealth and power: of the city by means of its empire, and of each individual within it, most of whom pursued wealth and power of their own. Fortune could be had through commerce, marriage or plunder, while fame, for those not talented in the arts, was available most lastingly by seeking political and military leadership. If politics was the best arena in which to win friends and a reputation, it was also a dangerous one: being held to account for bad advice or malfeasance in office could lead to financial ruin, exile or death, while any kind of prominence courted some risk of ostracism. Success or even survival of politicians and of people prominent for other reasons could come to hinge on their ‘ability to persuade by speeches judges in a law-court, councillors in a council meeting, and assemblymen in an assembly or in any other political gathering that might take place’, as the sophist Gorgias – a public figure in his Sicilian hometown of Leontini who is visiting Athens as a teacher – is made to claim in Plato’s writings.1

Despite the premium on public speaking in the Athenian democracy, the city offered no formal public education to teach young men how to do it. Thus advantage accrued to those who were able to seek private help in honing their speaking and arguing abilities, whether to pursue political ambition or simply to defend themselves should they be prosecuted. Rhetoricians and sophists flooded into Athens alongside home-grown varieties, all offering to teach ambitious young men how to speak persuasively to win power and prestige in the city. Some taught grammar, others etymology, others rhetoric – the ability to speak on either side of any question. These self-professed experts for the most part took the goals of wealth and power for granted, accepting them as the given ends for the individual and for the city alike, and focusing their attention on the clever means by which to outstrip others in achieving them. Excellence, or virtue (arete: the Greek word means the virtue of succeeding in carrying out an appropriate function), meant excelling in conventional political roles, getting the demos to accept one’s advice by whatever means necessary; this would bring the pleasures, wealth and honours to which most men aspired.

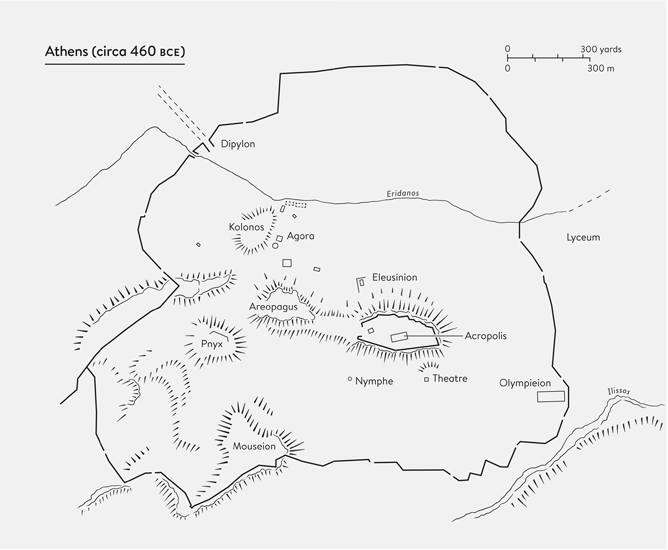

This was the cosy consensus that the philosopher Socrates (469–399 BCE) attacked. The son of a sculptor, he abandoned artisanal stonemasonry to spend his time challenging leading intellectual and political figures, as well as promising young men, to give an account of the values that they claimed to embody or wished to pursue. In so doing, he exposed blatant contradictions in the city’s priorities and in those of its most prominent inhabitants. He became notorious for spending his time in such questioning in the marketplace, in the gymnasium and in banquets and gatherings in private homes, rather than choosing to give speeches in the assembly or the law-courts (though he did his military service with distinction and served one year as a member of the lottery-selected Athenian council). Young men like Plato flocked to him, seeing in him an alternative model for living a good life to those that the city officially offered and praised.

When he was seventy years old, Socrates was accused by several fellow Athenians of having violated the city’s laws in ways that we will explore; he was found guilty by a jury of his peers and sentenced to drink poison. The drama of Socrates’ life, with his recurrent diagnoses of the moral and political failings of Athenian and foreign elite figures, and of his trial and execution became fodder for a group of his followers who wrote up their own accounts of Sokratikoi logoi, or ‘Socratic discourses’. None of them did so with more philosophical ambition than Plato (424–348 BCE), whose corpus of writings (almost all of which feature Socrates in a leading or minor role) has bequeathed us the description of ‘Socrates’ that will be the focus of this chapter. While the whole chapter draws on Plato’s writings and so bears the stamp of Platonic thought, the discussion of ‘Socrates’ (that is, Plato’s Socrates) in the first part of the chapter will look at those aspects of his life and death that several of his followers also recounted. The latter part of the chapter will discuss Plato’s own life, and will provide readings of several of Plato’s major works (one of them featuring Socrates as the lead discussant) in the course of doing so.

Socrates asks his fellow Athenians some difficult questions: if the city officially excoriates tyrants, why does it act like a tyrant abroad? Conversely, if it is wrong to aim for unlimited wealth and power for oneself, why is it acceptable for the Athenians collectively to pursue that via empire? Is it really courageous to fight battles without knowing the good for which one fights? Is it just, or pious, to propitiate the gods into turning a blind eye to one’s cutting of ethical corners elsewhere? He exposes the fact that hidden under the surface of what is said by sophists like Gorgias is a corrosive tension between individual success and collective flourishing. The art of rhetoric might be ‘the source of freedom’ for humans in general, but the sophist also presents it as ‘the source of rule over others in one’s own city’ for an individual who can use it to master the freedom of others. Concealed in the public celebration of rhetorical skill and political service lies the potential for an unscrupulous speaker to undermine democracy itself.2

In stark opposition to the virtually unchallenged adulation of wealth and power in Athens and in many other regimes, Socrates proposes that the meaning of the ‘virtue’ that young men are admonished to cultivate in Greek societies is the most fundamental question that a human being can ask, and a prerequisite for any politician worth the name. As he tells the jurors in Plato’s Apology of Socrates (a rendition of the speeches that Socrates had to make at his trial):

I went to each of you privately and conferred upon him what I say is the greatest benefit, by trying to persuade him not to care for any of his belongings before caring that he himself should be as good and as wise as possible, not to care for the city’s possessions more than for the city itself, and to care for other things in the same way (36c–d).3

If politicians and sophists are not similarly aiming to make men virtuous, what is the point of their powers of persuasion? But if they do not know what virtue is, what good are they? From the standpoint of Socrates and Plato, who pressed precisely these questions, all the existing answers – the intellectual and political life paths followed by the most promising youth and influential men in the city – were bankrupt. None of those leading these lives was able to define virtue or reliably to cultivate it in others.

Socrates raised such questions throughout the Peloponnesian War, at home and while away on military service. He became notorious enough to be lampooned on the comic stage by Aristophanes in three different plays (and by at least four other playwrights, too). In the first of these plays, the Nephelae (Clouds), produced in 423 BCE, Aristophanes makes him out to be a recognizable sophist, running a school for pay; yet he hints at something different about Socrates in suggesting that his intellectual attainments don’t offer his pupils any real road to the legal mastery for which they hope. Whether this was meant to be a critique of sophistry in general or a recognition that Socrates was distinctive in his abstraction from worldly measures of value, it was a lampoon that had no effect at the time on its subject’s carrying on with his activities.

Socrates’ notoriety, however, acquired a more sinister edge as Athens’ prospects in the war with Sparta darkened (and the later mentions by Aristophanes came in plays produced during that time, in 414 and 405). This shadow gathered with the accusations of impiety and treachery made against one of Socrates’ younger friends, Alcibiades, just as the Athenians were launching the all-or-nothing military expedition to Syracuse. It intensified further when the war was lost in 404 and the ‘Thirty Tyrants’ (also known as the ‘Thirty’) were voted in under Spartan pressure to form an oligarchy, expel many of the citizens from the city’s rolls, and rule by whip, force and knife. Two among them (Critias and Charmides) had been close associates of Socrates and relatives of his follower Plato. Socrates himself stayed in the city under the Thirty, seemingly having accepted enrolment in their list of purged citizens, at a time when most of those loyal to the democracy (including some of his other friends) had fled to the port.4 After that the democratic partisans regrouped to drive out the Thirty and re-establish the democracy.

It was in 399, five years after the restoration of the democracy, that Socrates was accused by three fellow citizens of not respecting the city’s laws, introducing new gods and corrupting the youth. This was not a direct reference to the coup of 404, since making a charge about responsibility for the short-lived and oppressive oligarchy would have violated a subsequent democratic amnesty barring any further prosecutions for them. But the jurors could not have forgotten the role that Critias and Charmides had played in the coup, or the various displays of impiety and treachery exhibited earlier in the war by Alcibiades. Those events made it easier for the prosecutors to paint Socrates’ distinctive life choices – reinforced, in Plato’s portrayal, in his refusal during his trial to play the expected rhetorical cards of begging for his life and flattering the jury – as violations of the standards of good citizenship defined by the city’s laws. He was convicted and sentenced to drink a poisonous cup of hemlock. His life and his death together served to change the agenda of what ethics and politics could mean. Socrates’ legacy, as shaped and expressed by Plato, transformed ‘virtue’ from being an accepted prop for current ideas of success into a reflective standard for ethical and political analysis.

Socrates in Action

As observed above, while ‘virtue’ is one English translation of the Greek word arete, another is ‘excellence’. In modern English, especially as inflected by centuries of Christianity, ‘virtue’ can sound quixotic, a trait designed to win otherworldly reward in the next life but not to gain any tangible benefit in this one. In ancient Greek, by contrast, arete meant the characteristic excellence that allows anything to flourish. A sharp knife has the arete of cutting well. Its virtue is precisely what allows it to succeed in its aims. The opposite of arete is not just moral vice but practical failure.

The Greek poets had praised virtue as taking several specific forms: wisdom; courage; moderation; justice; and piety. These, it was claimed, were dear to the gods and would lead to reward in this life and the next – as we saw in Chapter 1 with respect to justice in particular. But, as we also saw there, that story was becoming threadbare. It was too easy to point to examples of moderate men who suffered from the greed of others, or to just men who were victimized by the unjust, as the poet Hesiod portrayed himself, having been bilked of a land inheritance by his brother. And the links between the virtues were also easy to question. That someone might be courageous without being smart was a familiar idea at the time: consider the rather thick warrior Ajax in Sophocles’ tragic play of that name, railing against the decision to award the dead Achilles’ armour to the savvier Odysseus. More disturbing still were the voices that were being raised in late 5th-century Athens to call the just and moderate and pious man not smart, but stupid, obeying the rules and making sacrifices to the gods while others less scrupulous snatched away his land or money.5 Anxiety that the virtues might be conflicting and self-defeating raised the stakes of understanding the aims that a virtuous person might, and should, be trying to achieve.

In a city crowded with the posturing and the anxious, Socrates performs repeated acts of devastating exposé, asking those who should know best to say what the virtues are that they claim to possess. Again and again, they fail to do so, unable to state what excellence they can offer to teach or to exercise, and how it might relate to the broader aims of a good life. These failures cut to the core of the pretensions of the leading figures in the city’s political and intellectual life. Plato’s dialogues portray Socrates exposing two of Athens’ most admired generals as unable to define courage satisfactorily. Socrates demonstrates that the leading sophists, who claim to teach virtue, can’t even define it, and that self-appointed busybodies trying to enforce the laws about piety have nothing coherent to say about the nature of the piety that they are trying to enforce (not an unfamiliar spectacle to this day).

Each of these prominent figures has built his career on claiming to know certain things, yet each fails to explain satisfactorily what they are. As Socrates puts it in Plato’s version of the Apology of Socrates (21d), they do not know what they thought they knew. Because he himself does not indulge in such false conceits, he is motivated to seek knowledge by questioning experts who claim to possess it – even though again and again those experts disappoint him, some ruefully acknowledging their failure, others resentfully accusing him of mockery or manipulation. The knowledge that Socrates seeks is a knowledge of virtue and the good life. Without claiming to be able to define virtue himself, Socrates operates in his interrogations on certain assumptions that none of his interlocutors manage to dislodge: that to truly have one virtue, one must have them all, which means (given that wisdom is one of the virtues) that all virtue is, in fact, knowledge. One cannot be courageous without knowing what to fear, nor pious without knowing what the gods do and do not desire of humans, nor moderate without knowing what and how much to desire, nor just without knowing what one owes to others.6

Socrates’ search for virtue and knowledge – or, rather, virtue as knowledge – was a rejection of the alternative goals that transfixed many of his contemporaries. Power and wealth are unstable and unsatisfying, he argues again and again, not least because used ignorantly they are far more likely to harm their possessor than to benefit him. Only knowledge can ensure that we pursue goals worth pursuing, and only virtue is the possession of intrinsic and unconditional value, not contingent on the way that it is used. Socrates’ way of articulating the intrinsic value of virtue was to focus on the psyche, the Greek word roughly meaning ‘soul’. The psyche animates the body and can, according to Greek myth, be independent of it, reincarnated into varying bodies. Socrates insists that it is the purity and health of the psyche that is to be identified with a person’s well-being, the psyche that constitutes his very identity. What befits the psyche is virtuous action; what harms it is vicious action. Those who procure bodily pleasures by unjust actions – stealing or lying to support their desires for wine or food or sex – are making a profound mistake: they are pursuing pleasures that cannot benefit them, because they have sacrificed the most important and necessary good that they could possess in order to obtain those relatively worthless pleasures.

The final twist in Socrates’ conversations, as Plato depicts them, is that he himself claims not to possess knowledge of the most important things, and certainly does not claim to have the full knowledge that would constitute all the virtues. Yet he behaves in ways that strike onlookers as remarkably virtuous. He is moderate in his appetites, courageous in battle (he saves Alcibiades’ life but lets the younger man take the credit for bravery) and arguably a paragon of piety (despite the charges levelled against him in his trial). Most exceptionally, he places such a high value on justice that he argues that it is better to suffer injustice than to commit it. And when this argument is put to the test by what Plato and Xenophon present as an unjust verdict against him, he lives and dies by it, preferring to suffer an unjust sentence of death than to escape it by acting unjustly himself. The sheer depth of Socrates’ commitment to self-examination, his staunch rejection of the false gods of power and greed in favour of the value of knowledge and so of the continual search for it, shapes his outlook and disposition along virtuous lines. Even though he disavows full knowledge, Socrates’ valuing of knowledge and virtue above all else leads him to act more virtuously than anyone else around him.7

Socrates and Democracy

In challenging the claims of generals, sophists and others of his contemporaries, Socrates does not let the reputations of the famous Athenian political figures of the past escape unscathed. So Themistocles had won naval battles – but what good was the empire that had resulted? So Pericles had built the long walls around the city, filled its treasury with gold and silver, and adorned the Parthenon temple with astonishing marble sculptures – but could he point to a single citizen who had become more virtuous because of him? These men and others like them had even been fined or ostracized by the very people whom they had advised – proof that, rather than making their followers more just, as a really good politician would do, they had only made them more unjust. Sure, Socrates acknowledges, these famous men of the past ‘were cleverer than those of the present at providing ships and walls and dockyards and many other such things’ (Grg. 517c) – but they satisfied the citizens’ appetites merely, when they should have been forcing them to recognize that those appetites were not really worth satisfying.

This leads Socrates to a paradox. He himself had sought no fame through distinctive civic leadership. While he fought bravely in the Athenian army and took a turn in serving on the council, he made no speeches in the assembly, nor did he choose to frequent the law-courts. Instead he spent his time philosophizing, talking to people and asking them about virtue. It may not have been as recondite and pointless as measuring the jumps of fleas was made to appear in Aristophanes’ parody, but to men like the arrogant Callicles it would have seemed an ‘unmanly life’ – a life of ‘muttering in a corner with three or four boys, never saying anything worthy of a free man, important, or sufficient’ (Grg. 485d–e). Indeed, as Callicles warns Socrates – a warning that Plato was penning after Socrates’ death had already come to pass – if someone like him were to be accused ‘on the charge that you’re acting unjustly when you are doing nothing unjust’ (Grg. 486a), such a skulking good-for-nothing would be useless, unable to protect himself, much less to win any renown in the city.

Socrates is presented by Plato as making a bold riposte, by means of a characteristic kind of redefinition: claiming that he himself is the only one among his fellows ‘to pursue the true political art and to practise politics’ (Grg. 521d) in Athens. If politics proper aims at caring for the souls of one’s fellows, it is he alone who has done that. All the rest have sold their psyches, and their compatriots’ psyches, in the selfish pursuit of gain or fame.

By offering this paradoxical definition of the political, Socrates turned Athenian democratic reasoning on its head. Democratic politics was, as we saw in Chapter 3, about the power of persuasion turned to the end of majoritarian or communal profit and advantage. Socratic politics was about the power of argument in the form of rigorous questioning, turned to the end of individual virtue, which was the only genuine advantage, according to Socrates. As Plato’s Socrates says in the Laches, ‘It seems to me that to decide things well it is necessary to decide them on the basis of knowledge and not by the majority’ (184e). A true political expert would not be dependent on selection by chance or acclaim. He would be qualified by his wisdom and known by his deeds, by his ability to make his fellows more just – an ability that Pericles and company had failed to manifest not just in the city but also in their homes, where they were unable to point even their own children towards virtue.

For Socrates, if we cannot be as sure of our political leaders’ expertise as we are of our doctors or shoemakers in their own trades, we cannot hope to be well governed. Whereas democrats held that virtually any citizen was capable of judging correctly, Socrates insisted on a theoretical gulf between the expert and the non-expert – even while debunking all the putative experts and denying that he was one himself. To him, putting ignorant people in charge could not and would not achieve the highest aims of politics.

Socrates did not apply this stricture against rule by the ignorant to give a black mark to democracy alone. No regime – whether monarchy, oligarchy or tyranny – that was not ruled by people with knowledge able to direct their subjects to live well and to foster their virtue was truly admirable in his eyes. Virtue and knowledge are standards too high for any actual regime to meet very easily; by that very token, they set valuable critical measures for every regime, democratic or not. Socrates himself never lived anywhere but Athens, except when on military service: the city, for all its faults in his eyes, let him speak freely for decades and may also have informed his commitment to doing so through its political value of frank speaking. Yet many of his followers portrayed the Spartan habits of discipline and self-denial as more congruent with Socratic strictures than the free-and-easy, pleasure-loving and novelty-hungry Athenian ways (though Athens was widely acknowledged to be more hospitable to philosophy than Sparta).8 Many of those attracted to Socrates’ charismatic, unsettling presence took his elevation of virtue and knowledge as reason to denigrate democracy, even though they might also see some worthwhile aspects in it or remain democratic citizens in practice.

Socrates on Trial

Writing a version of the defence speech – in Greek, an apologia, the source of English ‘apology’ – given by Socrates at his trial (along with its companion speech proposing a penalty once he had been convicted) became a competitive literary sport among his followers in the wake of his death. Only two versions have survived. One is by Xenophon, an Athenian who had led mercenary troops into and out of Persia, fought with the Spartans against the Athenians, was exiled for it, and lived the rest of his life outside Athens despite an eventual reconciliation. In Xenophon’s version, each of the accusations made against Socrates – not acknowledging the city’s gods; introducing new gods; and corrupting the youth – is simply untrue. Socrates, for him, fits the existing model of an upright Athenian citizen perfectly, being distinctive only in his willingness to die so as to prevent his virtue from weakening in old age, and in his concomitant unwillingness to flatter the jury to avoid death.

In Plato’s version, by contrast, Socrates defends himself with attitude, along lines that are deliberately and dramatically different from the ways that upright Athenians at the time would have been expected to behave. Rather than humbly pleading or flattering the jurors, he tells them in no uncertain terms that, far from posing a danger to the city, he is quite literally god’s gift to it. He has been sent by the god to serve Athens by waking it up, acting as a good citizen not by the usual route of making speeches in the assembly or law-courts, but rather by questioning those he encounters about what they claim to know: ‘I was attached to this city by the god … as upon a great and noble horse which was somewhat sluggish because of its size and needed to be stirred up by a kind of gadfly. It is to fulfil some such function that I believe the god has placed me in the city’ (Apology of Socrates 30e).9

Even once he has been convicted and is invited to propose a counter-penalty to the prosecutors’ bid for death (Athenian law requiring the jury to impose either the penalty proposed by the prosecutor or that suggested by the defendant, with no compromise or alternative possible), Plato shows Socrates acting in a way that cannot fail to provoke the jury. His first response is that what he deserves is actually the same reward as that granted to Olympic victors: nothing less than free meals on the city for life (36d). Although he eventually proposes a fine as the official counter-penalty in an amount hardly proportionate to the gravity of the charges, it is little surprise that substantially more jurors vote to put him to death than had initially voted to convict.

The point is that Socrates’ values are antithetical to those of a typical Athenian jury. The jurors are accustomed to thinking of death as the worst possible penalty that might be proposed. But, since death affects only the body, not the psyche, which he insists is immortal, Socrates cannot possibly share that view. Indeed, putting his argument about virtue and wisdom into practice, he argues that, since he does not know whether or not death is to be feared, he does not fear it and nor should anyone else (offering a general and philosophical claim about death, in contrast with the reason for avoiding death that in Xenophon’s version is kept purely personal). Since death is the worst that the prosecutors can ask the jury to impose, but death cannot harm his psyche and so cannot harm the real him, Socrates has no reason not to accept the jury’s sentence.

The only possible exception is hypothetical, since it is not a penalty that any real Athenian jury would have inflicted: Socrates remarks in Plato’s Apology (29c–d) that, had the jurors imposed a penalty on him of ceasing to philosophize, he would have disobeyed that penalty. Such a penalty would have set a human jury against Socrates’ understanding of a statement by the divine oracle that no one is wiser than Socrates, one that Socrates has sought to prove valid by examining all the self-proclaimed wise men whom he encounters. It would be impious and unjust for him to disobey his interpretation of a divine claim. But, short of that hypothetical case, Socrates is content to suffer whatever harm the Athenians believe they can do to him, secure in the conviction that physical blows, impoverishment, even death, insofar as they do not harm his psyche, do not actually harm him at all.10

Having been convicted and sentenced to death, Socrates is thrown into gaol to await a propitious day for his execution. Plato shows him rebuffing an entreaty by one of his close friends, Crito, to escape. Crito has set up the whole plan: he can bribe the gaoler and spirit Socrates into exile. It was not uncommon for Greek defendants to escape death by so exiling themselves, and, so long as they did not return to their homeland, they were likely to get away with it. But Socrates refuses. He will not be doing harm or injustice by accepting his punishment; therefore he has no affirmative reason to escape it.11

Socrates’ philosophy does not direct him to defy the city. Indeed, it directs him to civil obedience, not to civil disobedience, though modern scholars preoccupied with justifying civil disobedience have often wished or imagined that it were otherwise. In his own political life, Socrates upheld the law (as he says, he resisted the putting of an unlawful proposal when presiding in the assembly as one of the councillors taking that role in turn);12 refused personally to commit injustice and punish an innocent man (as he says he did when he refused to follow an order from the Thirty to round up an innocent man for execution); and chose to suffer injustice by staying in gaol to be executed, since that did not involve him in committing any injustice. Yet he did not find active democratic politics to be a forum for meaningful action. Insofar as everyday politics was insensitive or indifferent to the quest for virtue as a critical and probing self-examination, it was not the arena for him. Indeed, his efforts were devoted to encouraging and prodding his fellows to pursue virtue and knowledge just as he did, trying to improve them individually rather than setting out to use political mechanisms to improve the city collectively. Perhaps he took it as a foregone conclusion that no one could succeed in using those mechanisms in a city where most individuals were motivated by greed, lust and power. If Socrates was going to change Athenian politics, he was going to do it one citizen at a time, by cross-examining one person in a way that might cause him to challenge himself, or that might bring an observer to engage in a self-examination of his own.

Enter Plato

Socrates spent his life speaking – not to the assembly or the courts, but to individuals and small groups, challenging and questioning them. He was neither an orator nor a teacher: he did his characteristic work outside formal institutions, individually and informally. Plato, by contrast, spent most of his adult life writing and teaching, as founder of an institute of higher education named the Academy, after the gymnasium where Plato and his followers had first gathered to talk about mathematics and philosophy. We know very little about how exactly the Academy functioned, though we do know that there were exercises in mathematics and logic, the practising of arguments and public lectures. At least one woman attended dressed as a man;13 many other Athenians of varying social classes were drawn to study, alongside a large group of foreign students like Aristotle. We have just tantalizing hints about the oral teaching offered there.

What we have in the main are the Platonic writings, and, in particular, his writing of dialogues – a form that seems to have been invented by him and others especially to convey the indelible power of conversations with Socrates. Socrates is the principal character in most of Plato’s dialogues and a minor character in almost all the rest; only from a single dialogue, the Laws, is he absent altogether.14 All these works were, we think, written after Socrates’ death, an event that prompted Plato to abandon Athens for a time, spending years travelling abroad before an eventual return.

Here was a young man born to an influential family (related through his mother to the revered legislator Solon, and to Critias and Charmides, who would become infamous members of the Thirty Tyrants) in the city that was a hub of artistic and intellectual explorations and at the zenith of its imperial strength. For such a rich and well-bred Athenian boy, opportunities to win renown were manifold. He could have become a general like Pericles, a playwright like Euripides (indeed we know that the young Plato wrote tragedies, which he burned upon meeting Socrates), or an historian like Herodotus, reciting his histories for public adulation at festivals.

All of these would have been paths to glory readily recognizable to his parents and his friends. But Plato chose none of them. Instead he spent his formative years captivated by an ugly man bred to a trade rather than born to wealth and aristocratic standing: that is, by Socrates. Plato forswore democratic politics as well as immediate oligarchic ambitions to spend his time watching and listening to his mentor’s endless questioning of others. If we imagine his mother and stepfather distraught at the thought that their son had been brainwashed by a cult, leading him to abandon all plans and ambitions for a successful life by any traditional standard, we are probably not too far off.

When Socrates drank the hemlock in 399, Plato was about twenty-four years old;15 after sixteen years or so abroad, he returned to Athens to found the Academy and wrote most and possibly all of his dialogues thereafter. Strikingly, he chose to set all of his writings not in the time he was writing but in the previous century, featuring leading characters who had lived when he himself was scarcely born. It is like an ambitious American writer and thinker in 2014 setting all his works – all of them, every single one – in the age of Johnson, Nixon and Ford, obsessively returning to the shadow of Watergate and larding his writings with premonitions of it in earlier years. It is a tribute to Plato, in a way, that readers tend to overlook this peculiarity: his works give us so much information about the 5th century, bring it so vividly to life, that we think of them almost as products of the 5th century rather than forty-odd years later. But, in writing these retrospectives when he did, Plato may well have been commenting on the politics of his own lifetime as well as of that bygone era, and we can gain by bringing that doubled vision – an eye on the 5th-century literary setting, and an eye on the 4th-century context of production – to bear on his works.

The years from 384 BCE (the year he probably turned forty) to 348/347 BCE (the year of his death) were turbulent. The dominant position won by Sparta with its crushing of Athens in 404 soon evaporated in the face of constant jockeying for position and alliance between Athens, Sparta, Thebes and Persia, complicated by struggles for power within each of them. Then, eleven years before Plato’s death, Philip II was appointed regent of Macedon – a borderland territory ruled by the Greek royal house to which he belonged. He was amassing power in neighbouring Thessaly, and Athenian politics from that point was dominated and divided by the question of how to respond. Should Athens make war against him to defend its independence, as Demosthenes urged, or make peace, as advocated by his opponents? (Plato’s contemporary Isocrates would go so far as to see Philip as the potential saviour of a united Greece against Persia.) Platonic imagery and vocabulary have been shown to be prevalent in the later speeches of the peace party, suggesting that Plato’s thought was received and perhaps also intended as a counsel against renewed war.16

This was a turbulent period of history. Each city and ruler seems to have been jockeying for power for the sake of power itself, rudderless in terms of larger political principles. Ironically, while Herodotus had contrasted the moral clarity of the Persian Wars with the troubling internecine warfare of Greeks against Greeks in the Peloponnesian War, for most 4th-century Athenians even the latter war would have seemed in retrospect morally unambiguous. Athens was fighting for freedom against Spartan oppression, Athenian democracy against Spartan oligarchy. (Compare the way that the Cold War, for all its problematic moral and political aspects, sometimes nostalgically seems a simpler and morally clearer political era than those that have followed.) But the burden of Plato’s work is to challenge that simplistic and nostalgic confidence. For his dialogues – most set during the Peloponnesian War – suggest that even when the Athenians thought they knew what they were fighting for, they did not. They liked to think of their war against Sparta as a war for independence, freedom and democracy. But in reality, Plato implies, it had been a war for imperial power and loot, trampling on any concern for virtue or justice.

Thucydides and Socrates (to the extent that we can reconstruct his thought independently from that of Plato) had already initiated that line of critique of the Peloponnesian War. Plato would take it one step further still. One might have concluded from reading Thucydides that the problem was only imperial tyranny abroad; get rid of that, in the way that J. A. Hobson would counsel Britain before the First World War, and then democracy at home could genuinely flourish. Plato, however, suggests that the rot went deeper. Democracy at home was itself incoherent, confused about what was really worth having and doing. That was the root of imperialism: not just a mistaken foreign policy, but one that was driven by greed and the desire for power. Socrates had not succeeded in extirpating that lust and greed from every Athenian’s soul; indeed, he had scarcely succeeded in doing so from anyone’s. By writing, Plato could potentially reach a wider audience, not just pressing them to challenge themselves but offering them a new portrait of what justice really requires, what success might look like, what it makes the most sense to desire and to pursue.

The Republic: A Deeper Case for Justice

These are the very questions explored in the dialogue of Plato that in English we call the Republic, famous as the first comprehensive analysis of how the best life of which humans are capable relates to the best constitution for a city, making it a model for subsequent reflection on psychology and politics from Cicero to Augustine to Rousseau and beyond. Its title in Greek is Politeia – the idea of a broad ‘constitution’ that we discussed in Chapter 2; in the edition of the 1st-century CE editor Thrasyllus, it has an associated subtitle, ‘On Justice’, the idea that we treated as central to Greek thought in Chapter 1. As the title and subtitle suggest, the dialogue raises a fundamental question arising from this book so far: can there be a constitution, a political organization that is also a way of life, that is just rather than exploitative? The question is addressed in the main body of the dialogue by Socrates, in conversation with two brothers of Plato, drawing a portrait of a city in which political rulers, who should be also philosophers, are the servants of the people, not their tyrannical or exploitative masters. Because they are philosophers, they will rule with knowledge of what is truly good; thus they are able to shape the city’s actions as well as the citizens’ characters in line with this standard of genuine value.

Here is an alternative view of the goals of power, coupled with a radically revised view of the appropriate means by which to attain those goals. Neither rhetoric nor lottery nor even election plays the role here that such mechanisms did in democratic Athens. Instead, in this ‘beautiful city’ (Kallipolis), the rulers are decided on the basis of true merit of the kind that Socrates elsewhere envisions, reproducing themselves by eugenically prescribed couplings, followed by choosing and testing the most meritorious of the children to serve. All depends on knowledge and virtue, which – as we will see – come from the same root. Only in such a city can most individuals develop the self-control and discipline, shaped by knowledge, that will enable them to refrain from acting unjustly and so harming their souls. The beautiful city turns out to be the condition for all but an exceptionally philosophical few to be able to protect their souls.

The Republic begins with a traditional story about justice, told by a lucky old man named Cephalus. A metic who has founded a wealthy manufacturing business, but whose fortunes will be vulnerable in the oligarchic coups to come (one son will be murdered as a democratic partisan), Cephalus adheres to the traditional story about gods and virtue. That old story teaches that humans should be just on pain of punishment by the gods – ‘just’ meaning that they should pay their debts to gods and men. This story has worked for Cephalus. He has been lucky enough to be able to afford to pay his debts without hardship, and lucky, too, in not being visited by any Job-like misfortunes. He has cultivated the traditional virtues and been rewarded with a good reputation among gods and men. Meanwhile the physiology of age has weakened his bodily appetites to the point that they do not threaten to undermine his commitment to traditional piety and justice, linked in that paying one’s debts to the gods through sacrifices is a form of both.

But, for many people in this milieu, Cephalus’ story no longer works. We meet one of them early in the dialogue: Thrasymachus, a world-weary man from Chalcedon, in Athens on a diplomatic mission, who suggests that this form of conventional justice is really a con game.17 There is no such thing as ethically valuable justice, because there is no such thing as political justice. Every city is ruled by men who exploit their subjects in their own interests, and do so by defining justice in the rulers’ favour: ‘Justice is what is advantageous to the stronger, while injustice is to one’s own profit and advantage’ (344c).18 Thrasymachus means that if, for example, Cephalus pays his debts to men in Athens, he benefits the demos who are in power in that city. But the demos have set the rules to favour themselves (they may be exploiting aristocrats by denying the validity of debts owed to them, for example). So Cephalus, in paying his debts, is actually being exploited by the demos. More generally, in an exploitative world, being just and self-controlled is not the path to happiness. It is a form of self-abuse. Justice is not advantageous to the individual. It is, rather, a way in which the individual is taken advantage of, for the benefit of others.

Thrasymachus is uncompromising, and he is unmoved by the manoeuvres that Socrates goes through to try to persuade him otherwise. Socrates argues that rulers in the role of rulers must desire the good of their subjects; it is only in the role of money-makers that they may seek their own personal good. But, to someone who has painted such a bleak sociological picture, this kind of quibble is unlikely to be persuasive. Nor are the two brothers of Plato who are present in the discussion persuaded. But, they say, they want to be. The upshot of their intervention is that Thrasymachus may be going too far when he says that the individual can have no reason to be just. Even under conditions of inequality, the poor might have reason to respect property claims, if only so that their own meagre property will be respected by others.

Justice, brother Glaucon says, can in some sense serve the individual’s true advantage – but its service is only second-best. The best thing would be for the individual to be a tyrant: able to make the rules for others to the advantage of himself, exactly as the logic of Thrasymachus’ position had implied. And brother Adeimantus adds that the promise of divine punishment that played enforcer in the old story is bankrupt. Either the gods do not care about humans at all, or they can be bought off by prayers and sacrifices – used not to pay a debt, but to pay a bribe. Looking around the world – and here Adeimantus’ social vision does sound closer to that of someone akin to the biblical Job – he sees the unjust flourishing to the extent that he finds it hard to resist the conclusion that the gods allow themselves to be bought off, hence that there is no sanction for the old story on which one can rely. Both brothers, however, insist that they do not want to believe that the accounts they retail are true. These cynical arguments are what too many of the leading men of their city and visiting intellectuals have told them. They urge Socrates to defend justice by showing that it is actually advantageous to the individual – which, if it can be proved, must mean that Thrasymachus’ story is wrong, since justice would not in every case, then, be tantamount to exploitation.

Socrates undertakes to defend justice by making a famous move: analogizing the individual’s psyche,19 where they are trying to find justice, to a city. Let’s look for justice in the city as a model for finding justice in the soul, he suggests, as it is easier to read characters written in large letters than in small letters. The city he has in mind will turn out to have three parts; so, too, will the soul. Among their interrelations he will claim to discover the role of each of four virtues: wisdom, courage, moderation and justice. What is political here is not only the city and its special Platonic three-part structure; the division of the soul is equally political. For both city and individual are shaped reciprocally by interactions between them. If people pretend to value honour but secretly crave gold, as in the unstable regime governed by honour that Socrates later describes, the regime itself is liable to topple, because ultimately the façade will crack. (Think of the last days of the Soviet Union: in country after country, people suddenly saw that no one believed in communism any more.) If people crave wealth and luxury, the inequalities spawned by their pursuit are liable ultimately to overturn the economic order, since the poor will eventually figure out that they are more populous and therefore more inherently powerful than the rich. Or, if people are resistant to education and cling to their varying whims, they are likely to swarm around a charismatic figure and thereby risk letting democracy mutate into tyranny.

Only in the case of a city where education shapes minds and characters in mutually supporting ways will a regime be sustainable in the long term. Kallipolis will turn out to be the first sustainable city and so the only genuine form of rule at all – since all others ultimately turn out to be counterfeits or impostors. Instead of relying on the old story about divine reward and punishment, Socrates proposes that the rewards and punishment can be primarily understood as intrinsic to one’s own psychology. Even when one considers the afterlife, it, too, can be understood as responding to the choices made by people to pursue justice or injustice during their lifetime: this is expressed by Socrates in the telling of a myth at the end of the dialogue in which, while the gods and the fates govern the structure of the afterlife, each individual soul has the opportunity to choose his or her own next life (within certain limits set by chance) and will in practice do so on the basis of how justly or unjustly they have lived during their last one. Thus justice in the afterlife depends overwhelmingly on its intrinsic value in mortal life, not on an external and so potentially arbitrary set of direct divine rewards or punishments.

Socrates begins his discussion by sketching the origins of a city that seems to have no reason to become unjust – it is a city that is naturally just, perhaps. This is a rudimentary city with a simple division of labour: shoemakers trade their wares for food from farmers, for example. As long as the needs they satisfy remain fairly basic, at a simple rustic level of cooking and clothing, there is no motive for injustice – because there are no engorged appetites that would lead anyone to act unjustly. Each person contributes his skills to the city without greed for more than the modest rewards (a simple rustic diet) they bring him.

Glaucon, however, is not satisfied with such a city. To a rich youth who has grown up in Athens, the most sophisticated, art-loving and cosmopolitan city of his day, such rustic simplicity looks primitive. To mollify him, Socrates proposes to allow luxuries into their imagined city, feeding engorged appetites and prompting ever greater cycles of consumption. Those drive early city-dwellers to war, the pursuit of which requires warriors. Here Socrates makes an ideologically charged move. Whereas in democratic Athens the people themselves were also the warriors, he suggests that in the city they are founding a separate military class will be needed. These guards have the task of external defence, but they also have the role of internal overseers and protectors of the city’s constitution. Thus it is the task of guarding that is treated as the fundamental political task: guarding the constitution and guarding the city against outsiders. The class of guards is then divided into two, in line with military divisions between officers and soldiers: an older and wiser group are to serve as rulers over a younger group, who serve as their military auxiliaries. Rule thus enters the dialogue first within the group of guards, and only then is it extended, with the wise group ruling over all the citizens.20

What, then, are the real virtues of a city? They arise within and among these groups. Two are straightforward: wisdom is the virtue of the rulers, courage of the military auxiliaries. Moderation and justice, however, are relational properties. Socrates defines moderation as the agreement of each group that the proper rulers should rule: it involves the willingness of the other two groups, the soldiers and the rustic producers, to limit their own desires in line with the direction of the rulers – and readers will find out eventually that the rulers will direct their desires and appetites in line with what is good. Socrates defines justice as each group doing its own task. In the primitive city, this was a matter of instinct; in a luxurious city, constant vigilance is required to maintain this within the proper limits. Here Plato is indicting every regime in which people use rule to gratify their desires: tyrannies and aristocracies as well as democracies. Rule should not be seen as a tool to gratify desires, as the Athenian empire had used its power to do. Rule is to be harnessed to enable people to do what is just and right, by preventing them from conceiving and acting on the desires to do otherwise.

In a just regime, the virtues of the individual and the city fit together and mutually support each other. In an unjust one, the vices of the individual are constantly undermining social relations and threatening to worsen them, while social relations themselves offer incentives for further corruption. A virtuous circle or a vicious one: that is the political choice Socrates lays out. It is a choice that confronts modern polities as well. Does the society support sustainable choices and decisions by its members, or do the incentives for unsustainable behaviour shape destructive actions that thereby further undermine the value of the social contract?21

The Republic: Justice in the Soul

The Platonic ideal of politics is fundamentally different from the birth of actual politics as we have seen it emerge in Greece. In Greek history, politics was initially under aristocratic control, which was then challenged by the poor, seeking justice as protection against exploitation and slavery. In Plato’s ideal city, politics would perform the function of guarding the city, providing justice to all within it, in the sense of offering protection against being overcome by one’s own greed and lust by providing a guardian to shape desires. For Athenian democrats, justice was essentially protection against the overweening rich and powerful, along with the enjoyment of equal civic powers. For Socrates in Plato’s Republic, justice is essentially protection against developing one’s own longing to become overweeningly rich and powerful – a longing that would result in making one miserable rather than happy. Power is nothing without justice; seeking conventional power is a recipe for injustice.

What about the individual? Having offered a radically unconventional account of the structure of Greek societies by dividing citizens from soldiers, Plato now offers a radically unconventional account of the structure of the psyche of each living, embodied person. That there is a division between the reasoning, calculating part of the soul and the bodily appetites is something that a Greek would readily grant – thus giving Socrates two of the three parts of the soul that he needs to posit to match the structure of the city. Identifying a third part is trickier. Socrates suggests that there is a spirited part, which seeks to feel pride and avoid contempt. The spirited part will ideally side with reason against appetite, but, if corrupted, it may do appetite’s bidding instead.

Turning to how the virtues relate to the parts of the soul, Socrates suggests that wisdom and courage are, as in the city, easy to assign: wisdom belongs to the reasoning part of the soul, courage to the spirited part. Moderation is, once again, agreement by all three parts that reason should rule. But justice is, once again, elusive: for if all three parts agree that reason should rule, what does the justice of each part doing its own work add? What it adds is the relinquishing of a desire by either of the lower parts to rule in reason’s stead. Only if the lower parts pursue their proper objects within bounds, rather than seeking to usurp reason’s role, will they avoid the injustice of seeking to gratify lust or greed beyond the bounds of what is acceptable to reason.

All this involves a picture of politics that would be radically unfamiliar to the Athenians who were Socrates’ interlocutors, and to other Greeks at the time. Socrates indeed makes it clear that for this conception of politics to work, it would require a massive campaign of education – for the guards must not be corrupted by stories about injustice being rewarded by the gods (the stories Glaucon and Adeimantus recalled as all too familiar in Athenian culture in Books 2–3). Drama and epic poetry, and the musical modes in which they are presented, need to be strictly controlled so as not to incite inappropriate desires or attitudes. And this enculturation is ideally to be supported by a lie, one that the rulers themselves should come to believe, a lie about both the naturalness of the citizens’ kinship as citizens, and the self-evidence of the (real) differences of merit among them. This ‘noble lie’ is less of an instrument of political manipulation than is often charged, since the rulers themselves are ideally supposed to believe it. But it is certainly an instrument of an unyielding commitment to meritocracy, rooted in supposedly discernible differences of aptitude tested further by character and achievement. And it is also a form of creating a shared sense of political identity in the guise of a myth of kinship.22 Whether political regimes can altogether do without meritocratic divisions and myths of kinship is a question for readers of the dialogue to ponder. Certainly we find here the connection between politeia as constitution and politeia as a way of life, with the latter as the means to achieving unity in the former.

This is the point reached by the end of Book 4, when it looks as if the argument is complete. The twist comes in Books 5–7, where it turns out that if the rulers are to protect the city, rather than exploit it, they will have to be far more different from ordinary rulers in who they are and how they live than might have first seemed to be the case. They cannot be any familiar breed of wise folk. Instead they have to be the strange kind of people exemplified by Socrates himself: philosophers who are inherently motivated to pursue knowledge of what really is, of what never changes, as opposed to mere beliefs about what seems to be the case.

These philosophers may be female as well as male: those women who are naturally capable are to be trained in philosophy and military service, and to take turns in ruling alongside their male counterparts. And precisely because all the philosophers, female and male, have to be wholly devoted to their roles in ruling and guarding, and protected from the temptation to exploit their rule, they must have peculiar living arrangements imposed on them (the women liberated from the constraints of the Athenian household): they are to copulate and bear children at the direction of the older rulers for the good of the city, to produce the best offspring, who will then be raised collectively. Like the Spartans, they are to have common meals and, going beyond Spartan requirements, to own no private property themselves. In this way, they can best defend the city, while aiming not at their own benefit but at the benefit of their subjects (unlike the Spartans, who ruthlessly exploit their helot subjects for their own advantage).

The radical idea here is that a good society requires the abolition of property and family for the rulers. This deprives the rulers of any incentive for corruption, since they would not be able to accumulate any property without being found out, and, if they were to manage to accumulate it, they would have no one to whom to bequeath it. This is a paternalistic idea of politics that, for the time, goes further even than did Sparta in channelling reproduction and upbringing for the purposes of the community. Here eugenics is to be built into control of the very timing of conception among the military guardians, though it seems that no such restrictions are to be applied to the sexual relations of the agricultural and artisanal producers.

Without property or family, the ruling elite are to consider themselves brothers and sisters, transferring the power of familial ties to their affection for the city itself. The seeds of communism and feminism lie here in the Republic – as ideas of how radically one would have to remake society by pressing human nature into unconventional institutions, if the sources of greed and corruption are ever to be extirpated.23 Some see the abolition of family and property for the guardians as a sign that Plato cannot be serious. I see it as a sign that he knew just how seriously all cities would have to change if they were to earn the right to call themselves just.

What is certainly meant to be funny in the dialogue, however, is that after introducing these bombshells imposing female equality, but no family or property, on the guardian class, Socrates says that his most ‘ridiculous’-seeming proposal is still to come: that the guardians are to be not just clever men in the conventional sense, but actual philosophers – those skulkers in corners whom Callicles in the Gorgias had derided as unmanly. And these philosophers are to be educated not just in poetry, music and military matters, but in mathematics, astronomy and higher philosophical studies. Far from being irrelevant to the city, as Callicles had painted them, or dangerously inimical to the city, as Socrates himself would be judged by a jury of his peers, philosophers who combine knowledge and moral character are potentially the city’s saviours.

What are these higher philosophical studies? Plato calls them study of the Forms, and in particular the Form of the Good. But he gives only hints and pointers, most of them embodied in elaborate models and stories, as to what the Forms are, though we can say roughly that they are the universal, unchanging truths that explain crucial aspects of the particular, changing world around us, including such truths as equality, beauty, justice and, underlying them all, goodness. Goodness is the most fundamental Form, because it embodies the very essence of existing for a purpose, the quality that makes anything valuable.

The most dramatic story illustrating the role of the Forms is the story of the Cave, which Socrates tells as a parable of the education that cities provide and the dangers and difficulties of escaping it. In the parable, the life of humans in existing cities is compared with humans imprisoned their whole lives in a cave, fettered in such a way that they cannot see the opening of the cave or any of the natural light of the sun. All they can see are the shadows of the objects paraded behind their backs in the dim space artificially lit by a fire. Honours and prizes come to those who can best reproduce or talk about the shadows that they see. None of them is willing to accept that there is any such thing as a reality beyond the shadows, let alone beyond the cave.

The story suggests the intuition that truth lies beyond the horizon of what most people, trapped in the city’s fables of honour and value, can possibly conceive. The Forms are those truths about the essence and nature of reality. Just as the artificial cave-objects are seen only in the form of shadows cast by the man-made fire, so the Forms can be understood only in the light of the idea of the Good that is paralleled in the story by the sun. Philosophers are those who come, either by happenstance or by compulsion, to understand these truths. But trying to proclaim them to the inhabitants schooled in the ways of existing cities is a dangerous business. The cave-dwellers will not be inclined to follow anyone returning upward; they will rather say (Socrates suggests) that such an escapee has ‘destroyed his eyes’, concluding that ‘it’s not worth it even to try to go upwards’ (in other words, to get out).24

Hence the abiding paradox of the Republic. Philosophers are potentially the city’s saviours, but the citizens they would save are inherently disposed to resist and even to destroy those who offer such help. Any diagnosis of political unhappiness as profound as this one will face this kind of problem: if the rot goes so deep, whence – except from outside, or from someone who has been in a form of internal exile – can come salvation? The Republic’s way of squaring this circle is to posit that there might be necessities (whether human or natural) that would compel people to accept a form of help that they would otherwise scorn. It is a slim and vague possibility, but Socrates insists that it is a possibility nonetheless.25

Even if philosophers could somehow come to rule, there is a further question: how would their knowledge of the Forms help them to be good rulers? Socrates’ arguments in the dialogue never suggest that knowledge of the Forms alone is sufficient to make someone a good ruler. The identification of virtue and knowledge here, and elsewhere in Plato, goes both ways: if all virtue is ultimately knowledge, one cannot be knowledgeable without also being virtuous. In the Republic, Socrates tries to show how this might develop in someone with a philosophical disposition, suggesting that anyone with such a disposition will also be inclined towards asceticism in respect of bodily desires, and that this instinctive lack of interest in the bodily, compared with their love of knowledge, will incline them to developing good moral character and good intellectual achievements from the same root.26 Yet he acknowledges that this process can go awry, especially if corrupted by temptations from outside. Hence a well-ordered city like Kallipolis would have to take pains to test the moral character, endurance, memory and other requisite qualities of its aspiring philosophers before deciding which of them would make good rulers.

Once a select group who are intellectually and morally qualified is chosen, the question remains: how would they rule better than others by virtue of having knowledge of the Forms? A natural objection would be that politics doesn’t need highfalutin philosophical knowledge; it needs down-and-dirty abilities that knowledge of the Forms won’t provide, and might likely impede. But the Platonic answer is that deciding about particular cases – which is something the philosopher–rulers will emphatically have to do to manage the particularities of forming and educating a suitable next generation of themselves – is something that does require the illuminating perspective of the broadest possible understanding.

To know the Forms is to know what is real and unalterable and essential. The world can be understood and explained, can be intelligible, just insofar as it is understood in terms of the Forms (the rest is mere and inexplicable brute matter, which receives but also limits the shaping power of the Forms). Such knowledge of what is unalterable – the definitions of the virtues and the very idea of what makes any purpose or goal good – is to inform all the particular political decisions that the rulers make. They have to decide about particular cases. How should this child be raised? Is this aspiring philosopher intellectually up to snuff? These decisions are to be made in the light of an understanding of what is genuinely valuable.27

Here Plato completes the inversion of the usual view of politics that Thrasymachus had offered in such a dark and cynical tone. Conventional rulers rule for their own benefit; these newly fashioned Platonic rulers will rule for the benefit of those whom they govern. Their own benefit comes from the justice and other virtues that they enjoy owing to their own philosophical natures; the benefit to their subjects comes through the exercise of an art. Politics is not about one’s own advantage, in Plato’s view; it is not an exercise in self-interest, even if properly understood. Ruling others is a form of noblesse oblige, serving the true interests of those who cannot identify or attain them for themselves. The influence of the Republic lies in its connection between the value of virtue for the individual and the need for a certain kind of constitution in which those naturally capable of (and subsequently trained in) full virtue and knowledge must rule the rest in conditions of harmonious acceptance. This has attracted reactionary followers who have emphasized the elitism and hierarchy in Plato’s dialogue, but also progressive followers who have emphasized the ways in which the dialogue criticizes unmerited and socially divisive distinctions of gender and property.28 The Platonic vision of harmony within the individual, and between the individual and society, achieved by philosophical rule that serves the benefit of the ruled rather than exploiting them, has been influential precisely in having unsettled its innumerable and diverse readers (ancient and modern, Jewish, Christian and Islamic, conservative and radical) to the same extent that it has inspired them.

Political Knowledge and the Rule of Law

The pride of place accorded philosophy in the Republic is a strength, and a weakness. Its strength is in showing how ruling must be directed to valuable purposes. But its weakness is in treating politics as essentially derivative of philosophy. Just understand the Forms, add some practical experience and military training, and stir. In pointing to the knowledge of the Forms as what defines the philosophers and girds them for rule, the dialogue does not ultimately answer the question ‘What is the political art?’ with any insight that is specific to politics.

In another dialogue, the Statesman, in which Socrates is a bystander while the leading role is taken by an unnamed Visitor from another Greek city (Elea), Plato does define political knowledge head-on. He does so in tandem with an effort to define its counterfeit. He inquires first into the sophist, the person with the illusion of political knowledge, and then into the statesman, the expert political knower. But what is it that the expert political knower knows? He knows how to rule over other human beings – it’s not as if he is a shepherd ruling over a speechless flock. As in the Republic, ruling over people is benefiting them – but how are people actually benefited? The statesman is not a doctor, able to heal people; not a baker, able to feed them; not a general, able to defend them. The closest arts to his are those of the general, who knows how to wage war; the orator, who knows how to persuade; and the jurist, who knows how to resolve disputes among citizens, oversee contracts and determine what is just. These three figures themselves may seem to embody and exhaust all important political roles: after all, when the Athenians spoke of their political leaders, they spoke of ‘the generals and the orators’ (hoi rhetores kai hoi strategoi). But to the Visitor from Elea, there is a special role for a statesman above and beyond the roles of the generals, orators and jurists (jurors and, in the context of dramatic competition, judges) who populate the Greek political scene. That role is the knowledge of timing. What the statesman knows is when to direct the generals to make war, when peace; when to instruct an orator to give a persuasive speech; when it is appropriate for jurists to make a judgement. He does not determine when in a vacuum: he knows when to take these actions for the best, for the forming of a virtuous citizenry and for the true advantage of the city.

Another way to put this is that the Statesman introduces a new idea of what ruling means. For most Greeks, the rulers were the people who held the offices in the city: who were generals or treasurers or ephors; or, perhaps in a democracy, the councillors and by extension the jurors and assembly attendees. The Visitor from Elea, however, suggests that there is a function of ruling that is above all that. Yes, a city needs generals and orators and jurors and judges. But to weave together its citizens in virtue and enable them to achieve good aims, those offices and the corresponding arts are not sufficient. True politics requires a grasp of good timing that can direct the deployment of each of these subordinate arts. The true statesman transcends these given political roles and inhabits a new one: that of overarching coordination for the best.29 Politics requires unity, as in the Republic; here we learn that unity, in turn, depends on the coordination of timing with an eye to what is best.

Such coordination works also on the temperaments and outlooks of the citizens. For political strife and damaging decisions arise from ingrained divisions of outlook. The dialogue contrasts the people who tend to be slow and steady with those who are more impetuous and daring. Think of the classic contrast between hawks and doves. Left to themselves, two such groups might routinely clash in ways that further widen the gap between them – for they are unlikely to intermarry or to interact, loath to associate with those whom they find so temperamentally alien. The danger of citizens finding themselves alien rather than kin to one another – which can spur civil war – is perhaps the deepest political danger of all. The statesman’s role as described at the end of the dialogue is precisely to set up the educational bonds and to encourage the intermarriages (we might think more broadly today of all kinds of social interaction and diversity policies) that can avert that danger. By enabling people to share evaluations and perspectives, they can develop common judgements that will make them more appreciative of each other and more likely to gauge the policies best suited to the changing times with accuracy.

A final contribution of the Statesman is on the role of law – and in particular written law – in politics. For if political knowledge is key, and if political knowledge is now understood to be knowledge of timing, knowledge changing with circumstances and involving personalized advice about what to do for the best (like the advice of a gym trainer or doctor), how can it make any sense at all for political life to be governed by laws? Laws are exactly the opposite of precise and personalized: they are ‘stubborn and ignorant’. (Think of the three-strikes laws that force judges in many American jurisdictions today to impose harsh sentences on nonviolent defendants at great social cost.)

Ruling by law seems to be a prescription for unvarying and therefore imprecise policies, at least compared with what an expert statesman could advise were he or she to materialize. And law normally takes the form of written law – especially in democracies, proud of the accountability embodied in written laws, as we saw in Theseus’ speech in Chapter 2. Yet, to the Eleatic Visitor in the Statesman, writing down laws only exacerbates the dangers of rule by law. For, even though writing per se is not the problem – doctors might use writing to dash off a new prescription – the idea of permanently engraved laws on stone tablets and public walls makes writing part of the fixity problem. The Statesman shows that, while polities may inevitably need laws, in that even the best statesman, like the best doctor, will use written law as a tool, it is a mistake to define political rectitude in terms of law. Law is merely a possible tool for rule; only political knowledge embodies the reasons that can make rule good.

Despite these strictures against law as imprecise with regard to political knowledge, another one of Plato’s dialogues makes law central to the life of another imagined polity. The Laws is the only dialogue in which Socrates does not appear at all, although aspects of his ideas in other works are repeatedly referenced. Here, three old men – a Visitor from Athens, a Cretan and a Spartan – are making a pilgrimage to the cave of King Minos on Crete when they begin to discuss the best laws by comparing those of their home cities. Crete and Sparta were famous as societies governed by ancient codes of law, sharing the Doric dialect of Greek and a common militarist outlook focused obsessively on training young men in courage and in the techniques of warfare, contrasted with the Athenian cultivation of rhetoric and the arts. The Cretan character eventually reveals himself to be a member of a group about to found a new colony, and invites his pilgrimage companions to turn their comparative and historical conversation to the project of founding laws as if for that new colony.

Thus the Laws, like the Republic, is a project of founding a city in speech – and, while the Republic’s interlocutors also proceed by drawing up laws, the Laws does so in far more detail.30 Moreover it draws up laws for a regime in which philosophers do not seem to exist: the term ‘philosophy’ is used in varying grammatical forms only twice in the dialogue. This is a city that is self-avowedly second-best to the ideal city of the Republic in which private property was abolished for the rulers.31 Instead, property here is allowed – resulting in four wealth classes of citizens, comparable with those that Solon established in Athens – but the citizens are directed towards using their property for civic ends. The main mechanism to direct them is the law. Instead of being a shorthand tool for a busy expert, law is here reconceived as an embodiment of divine reason. The citizens are to see the city as founded with the aid of the gods; those inclined towards atheism will be given reasoned persuasive arguments to believe in the gods. Piety, which was absent as a major virtue from the Republic, is the cornerstone of civic life in the Laws.

With that divine sanction, the citizens are to be conditioned to love and obey the laws from birth, and even before birth (the dialogue goes into detail about the best rules of music and exercise for pregnant women). The laws themselves shape a balanced constitution that is a mean between ‘monarchy’ and ‘democracy’ (693e).32 The citizens are to accept rule ‘voluntarily’ – yet their doing so is shaped by the persuasion and compulsion exercised by the lawgivers. For those forces to work, the city must be relatively insulated and isolated, sited away from the temptations of the coast. Only a few citizens will be given permission to travel abroad, and then mainly to learn whether there are any features of other societies that can be beneficially incorporated in their own. The Laws offers a picture of a modified Greek society, in which citizens govern themselves rather than being governed by godlike philosophical guardians, but are kept in line with virtue and goodness by strict obedience – even memorization – of a law code that is eventually to be made fixed and virtually unchanging, treated as if it enjoyed the status of the very divine law with which Antigone had contrasted human laws (Chapter 1).33

If the Republic offers a Platonic aspiration to philosophical rule, and the Statesman explains what makes ruling knowledge genuinely political, the Laws evinces a good city that lacks precise philosophical guidance, yet that can keep itself on the rails of virtue by strict obedience to its given laws. Some see the Laws’ emphasis on the divine sanction for obedience as a contradiction of the Socrates who would not have obeyed a verdict telling him to stop philosophizing. But that same Socrates obeyed the verdict that imposed his death. If the Republic imagines a city in which someone like Socrates could use philosophy to benefit his fellows (rather than be seen by them as a danger), the Laws gives us a city in which a decent life can be lived without the direct rule of philosophers – since they are so hard to find and to entrust with power without the danger of corruption. Notwithstanding the establishment of an elite council to meet at dawn, charged with amending the laws if necessary and with overseeing influences from outside the city in doing so, the Laws most significantly embodies wisdom not in individual philosophers, but rather in the content and authority of law.

Plato at Sea

Alongside Plato’s dialogues is a tantalizing but problematic source: a series of thirteen letters said to be by him, but almost certainly written by others – the writing of letters attributed to famous personages being a favourite literary pastime of antiquity. Yet scholars are still divided over whether the ‘Seventh Letter’ might be genuine.34 It would be an amazing source if it were, and, while I think its genuineness is unlikely, the letter is still instructive as to the views of Plato held by his followers. For it purports to present Plato in his own voice recounting his disillusionment with politics after the death of Socrates, and then telling the tale of three journeys that he made to Sicily in later life, trying to convert to philosophy a young man born to inherit tyrannical power: first to educate the young man, in partnership with his adviser and close Platonic friend Dion in 388; then to treat with him as ruler (Dionysius II) in trying to protect the banished Dion in 366; then again in 361–360, when the suspicious Dionysius II kept him in close confinement while Plato tried unsuccessfully to persuade him to let Dion return from banishment.

All three visits ended ignominiously. Plato was sent home the first time on a Spartan ship whose captain was bribed by Dionysius I to sell him into slavery; he was imprisoned the second time before being released; and he was threatened by Dionysius II’s mercenaries on the third voyage. (The mercenaries hated him because ‘they believed that he was trying to persuade Dionysius to give up the tyranny and live without a bodyguard’ (Dion 19.5).35) We must take these details with a large pinch of salt, since later Greek historians and biographers disagree about many of the details of the travels, including even the number of trips that Plato made to Sicily.36 Nevertheless, it is fascinating to imagine Plato trying to cultivate a philosopher–ruler in person.