During those early years, I bounced between three different households—Mom’s apartment, Dad’s place, and Bunny and Herb’s apartment in Marina del Rey—and all three were a little crazy. My father was a famous entertainer, my grandfather represented entertainers, and my mother wanted to be an entertainer. So I guess it should come as no surprise that I wanted to be an entertainer, too. And, as everyone knows, most entertainers are nuts.

When I was only nine years old, my mother introduced me to the circus, and, more specifically, to the world of clowns. Years earlier, in New York, she had become a self-taught photographer, and she got a job taking pictures of the clowns at the Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus. She did such a good job that her friends would call whenever the circus came to town, and we’d go off to see them.

I don’t know what it was about clowns, but they absolutely fascinated me. I loved the fact that a normal person could paint his face, put on a big red nose, slip into a pair of large, floppy shoes, and become a completely new person. I know it’s similar for actors, but it’s not exactly the same: when a person becomes a clown, the transformation is complete. And the notion that one could become a wholly different person, that really appealed to me. (Gee, I wonder why?)

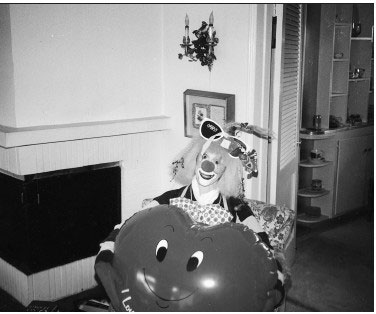

My mom and I almost ran off and joined the circus. Here she is in the early 1980s.

Whenever the circus was in town, I always rode in the parade, and whenever the clowns walked into the audience, to invite someone into the ring, they invariably found me. The first time it happened, I felt like the luckiest little girl in the world, and as it continued to happen—I got picked every year, year after year—I finally figured out that Mom was behind it. These were her friends, after all, maybe her only friends, and they would do anything for her.

One of the clowns, Skeeter, a black man, became my mother’s boyfriend for a time, and he was endlessly entertaining. We played cards together, spent hours hovering over board games, and even practiced magic tricks. He also bought me a parakeet named Twinkles that I was absolutely crazy about.

Once, at school, I drew a picture of Skeeter in an art class, and I was reprimanded by the teacher. “Now, Rain, you know there’s no such thing as a black clown,” she said.

“Yes there is,” I insisted. “There’s Skeeter. And sometimes he lives with us.”

My teacher didn’t believe me, and I couldn’t convince her otherwise. I went home, wanting to ask Skeeter if he could come to school with me the next day, and talk to the teacher, but he was gone by then, off to entertain audiences in other cities.

My fascination with circuses continued into my preteen years, and on one occasion, we went to see Circus Vargas, one of the more modern, European-style troupes. My mother brought her camera, befriended the clowns, and had such a good time with them that she decided to launch a new career. For the next two weeks, she worked with the clowns of Circus Vargas, developing a character of her own—a whimsical, childlike figure called Papillon—and entertaining audiences. I went to most of her performances, and I was enthralled by the transformation. My mother was gone, and Papillon had taken her place. I definitely liked Papillon better.

Often, her fellow clowns took me aside and taught me a few things about the profession. I learned a few funny magic tricks, some basic acrobatics, and how to juggle.

“You know what?” my mother said one night, unable to contain her excitement.

“What?”

“We’re going to join the circus.”

“What do you mean?”

“You and I,” she said. “We’re going to run away and be clowns together!”

I thought it was a great idea, and Mom began looking into the possibilities. She made some calls to inquire about tutors, so that I wouldn’t fall behind in school, and we even ran around looking at used trailers which might serve as our future home.

“This is going to be the adventure of a lifetime!” she assured me. “We’ll be together all the time. We’ll be happy and things are going to work out and I’ll become the mother you deserve.”

I was thrilled. I was too young to understand the depth of her pain. I was too young to see how badly she was hurting inside.

“A fucking circus!” Dad bellowed when he was told about the plan. “No daughter of mine is goin’ on the road with no motherfucking circus!”

That was the end of that dream, and for a while I was completely crushed, convinced I would never recuperate.

Dad—being Dad—made up for it in other ways, of course. The next thing I knew I was being whisked off to all sorts of exotic locations, along with Elizabeth and Richard Jr. We were his three eldest kids, and we certainly got the best deals.

His favorite places were London, Paris, Hawaii, and Jamaica, and I went to all of them.

When we went to Paris, we flew on the Concorde and hopped into a waiting limo for the ride to the swanky George V Hotel. It was the most elegant place I had ever seen in my life. The doorman wore white gloves and bowed as we came through.

The thing I remember best about Paris were the dogs, which were absolutely everywhere, even in all the finest restaurants. Lots of restaurants had little mats under the tables, where the dogs could nap as the owners dined. The other thing I remember is hearing little kids talk French. I thought it was the most amazing thing in the world. I remember pointing this out to Elizabeth, telling her, “Isn’t that incredible? Little kids, five and six years old, and they speak fluent French!”

“Rainy,” she said, “they speak French because they’re French. And French is all they speak.”

Well, duh.

One year we went to Paris with what seemed like all the siblings, and Daddy took us to see Silver Streak, a movie he’d done with Gene Wilder and Jill Clayburgh. The movie was dubbed and my on-screen Daddy was speaking French, which I found hilarious.

After the movie, on our way back to the hotel, Daddy had the same question for each one of us.

“Elizabeth, who is your favorite comedian?”

“You, Daddy! You!”

“Junior, who is your favorite comedian?”

“You, Dad! You!”

“Renee, who’s yours?”

“You, Daddy,” she said, but she said it without much enthusiasm.

Then it was my turn. “Rain, who is your favorite comedian?”

“Steve Martin, Daddy! Steve Martin!”

He was laughing, but I could tell he was a little pissed off. “Well, let’s see if Steve Martin gets you any Christmas presents this year,” then he looked away and mumbled: “Fuck Steve Martin.”

Dad with Gene Wilder in Silver Streak

I liked London, too, especially the accents, and I remember watching the changing of the guard at Buckingham Palace, and going to the Tower of London, where they used to torture people. Apparently, the British were very big on torture—it seemed almost like a national pastime. I went to Madame Tussaud’s, too, and at first I couldn’t believe that the wax figures were made of wax. I was sure they were real people, standing very, very still, and that at any moment they were going to leap out and scare the bejesus out of me. I wasn’t a fan of being frightened. I remembered Daddy’s basement, and the day I watched Linda Blair in The Exorcist, hurling pea soup clear across the room, her head spinning completely around.

I was also kind of impressed with the notion of celebrity. When we were back in Los Angeles, we didn’t go out much. We mostly stayed home, and people came by the house, and my dad was just a regular guy. But here in Europe, people recognized him wherever we went, and they asked for autographs, and he was always very polite and accommodating. The only time it bothered him was if we were in the middle of dinner. He hated it when people interrupted our family meals, but he was nice about that, too. “Let me finish having dinner with my family,” he’d say, “and if you’re still here when we leave, I’ll be happy to have my picture taken with you.”

I’ve got to admit, I liked the attention. I felt a bit like a celebrity myself, especially when we were riding around in limos. There’s just something about limos that makes this girl go weak at the knees! And I liked the power of celebrity. I knew my father wasn’t God, of course, but sometimes people treated him as if he were—the God of Comedy?—and it didn’t seem like such a bad thing at all.

As the years passed, Daddy seemed to find us kids increasingly entertaining. We were kids, but we weren’t babies, and he seemed to enjoy watching us evolve. When he was funny, we got it, and we laughed, and I think that meant the world to him.

I remember going fishing with him once or twice, and feeling like a regular family. Daddy would teach us all about bobbers, show us how to fasten a lure or bait a hook, how to cast, and how to snag those babies when they bit. We used to catch small trout and even smaller porgies, and Dad would get so excited every time we caught something that he’d clown and jump around and act like we’d snagged a motherfuckin’ shark.

Sometimes we’d take the fish home and he’d gut them and clean them, showing us how it was done, and then he’d throw them on the grill with a little olive oil, and lemon from our own lemon trees, and we’d enjoy the fruits of our labor. I always loved those times because it was as domestic as he ever got, and he seemed just like a regular father.

But he wasn’t a regular father. He was an artist, and he was hugely successful, and most of the time he was consumed by his up-and-down career.

In 1977, for example, when I was eight years old, he had a series on NBC—The Richard Pryor Show—and right from the start it seemed to be in trouble. I was too young to know what was going on, but from what I heard he was a little too “out there” for the censors. It really pissed him off. One night, back at the house, he was addressing his entourage, and he was fuming. “This nigger’s not going to let anyone tell him what he can and can’t say,” he said. “I’m not changing a motherfucking word for those people.”

He didn’t change a word, and the show was canceled after only five episodes.

My father’s NBC show was short-lived.

Dad was living with Deborah McGuire at the time, whom I’d seen around, and in September of that year he went off and married her without telling anyone. I liked Deborah. She was slim and black and wore her hair pulled back in a tight bun, and she always looked elegant as hell. I also liked her because she never took any shit from my father. One night, though, probably still reeling from the losing battles with the NBC censors, Daddy walked out into the driveway with his .357 Magnum and filled Deborah’s car full of holes. That was the beginning of the end. Deborah was a tough broad, and Dad had never once raised his hand to her, but his bullshit was getting way beyond acceptable.

There was another woman on the periphery back then, Jennifer Lee, who was actually one of Dad’s employees and who took care of a lot of his day-to-day business. She was very attractive, and she seemed to have her eye on Dad. For some reason I couldn’t understand why I didn’t like her at all. I don’t know what it was—call it Rainy’s intuition—but I knew she was trouble.

Jennifer also happened to be white, and by this point, I was at an age where I was becoming more acutely aware of race.

At the time, I was in the fourth grade, and one morning a skinny red-headed kid with freckles pushed me to the ground and called me a “nigger.” I had heard my father use the word, and I had heard plenty of other people use the word, but never with that nasty edge. So I went over and called the kid a “motherfucker,” like I’d heard my parents call each other, and buried my teeth in his arm.

I got called into the principal’s office—and, mind you, the principal was black—and I was severely reprimanded. After school I told my mother all about it and she went absolutely ballistic.

Dad with Deborah McGuire, the one wife who took no crap from him.

The next morning, she accompanied me to school and marched me into the principal’s office. “You’ve got some nerve!” she hollered. “You’ve got a little white, red-headed motherfucker calling my girl a ‘nigger,’ and she bites him, and she’s the one who gets into trouble! Something’s wrong with this picture!”

“Ma’am, I’m going to ask you to watch your language.”

“Watch my language! You ain’t gonna ask me shit, motherfucker! You going to find that little honky kid and have him apologize to my daughter.”

I never got the apology, but the honky kid heard about my mother’s visit, and he heard she had scared the principal, and he steered clear of me forever after.

Man, Mom was pissed—and I loved her for it. Someone had called her baby a “nigger,” and she was indignant, and she had come to my defense. That’s what mothers were supposed to do. They were supposed to protect you. And she’d done it.

It helped, of course, but it didn’t change my world. For years to come, the black kids would tell me I wasn’t black enough, the Jewish kids would tell me I couldn’t possibly be Jewish, and even some of the teachers got into the act, albeit not always deliberately.

“How come I’m the Gingerbread Girl? I want to be Raggedy Ann.”

“Rain. Look at your skin. It’s brown.”

Man, why don’t you come out and say it? Say the fucking word already!

I was used to hearing it, of course, but in Daddy’s house the word “nigger” was always an expression of love. It was never “nigger,” though: it was “nigga.” Nigga, get this nigga a drink! Nigga, get your black ass to bed. Nigga, put that pipe down before yo’ mothafuckin head explodes!

Interestingly enough, after that incident at school, my mother asked Mamma if she would please talk to me about race. I was a biracial child, but people thought I was black, and they identified me as such, and my mother thought I should get a handle on my ethnic identity.

I remember Mamma taking me aside one day, with her tarot cards, and she began by talking to me about the cards, teaching me what each card meant, and how the position of the cards always affected one’s interpretation. Then she paused to shuffle them, and she began to talk about the subject that was really on her mind.

“If you black, you is a nigga in my house,” she said. “And you black, Rainy. The world’s gonna see Rain as a nigga no matter what her mother is. So nigga it is. But remember this: in my house, nigga is a term of endearment. People say, Nigga, please! Or, Nigga where you been at? Or, Don’t fuck wit me nigga cause I’ll stick my foot up yo’ ass! But it don’t mean shit. The word nigga only mean shit if you make it shit, and people who make that word shit—well, those people ain’t welcome here.”

“What about ‘honky’?” I said. “Can that be shit if you make it shit?”

“Honky! Hell no! That word don’t have the same punch now, do it? Honky never hurt a white man’s feelings, no matter how harsh you deliver it. It ain’t got no edge. But the word nigga—that word’s got power. Wrong man uses that word, it’ll put sweat on your palms and make your heart race.”

“So that boy who called me nigga, he was wrong?”

“He sure enough was!” she said, her voice rising. “He don’t have a right to call you nigga. If you want my opinion, I don’t think any white man has the right to call a black man nigga. That word don’t belong to them. It’s our word, and only we know how to use it right. When a white man uses that word, nine times out of ten he means it hard.”

After Mamma went back to Illinois, my own mother took off on an extended trip, to places unknown, and I stayed at my daddy’s for several weeks. He was in a lousy mood, and it seemed like every day he’d scream at me and beat me for no reason.

Many years later, when I was an adult, I tried to make sense of his erratic behavior in a letter to Elizabeth. I wrote her as follows:

For me there is nothing normal about how I grew up and how we grew up with him. I have forgiven Daddy for being a shitty dad because he really could not have changed. I believe Daddy was also mentally ill, that he was bipolar and never took medication for it. I believe that’s why his actions had no rationale, why his anger was so quick. Yeah, I know the cocaine and the alcohol didn’t help, it just made it worse. Do you know he made me get his cocaine for him one time and cut it up? Then one day he blamed me for his addiction and I swear I felt like killing myself.

It sounds like I was exaggerating, but I wasn’t.

When my mother came back from her mystery trip, she was in a foul mood, too, so the moon must have been in the wrong motherfucking house. Day after day, she would rage about the fact that nothing ever went right for her, and that she could never catch a goddamn break. “It’s your motherfucking father!” she bellowed. “He never raised a hand to help us. I have to do everything for you!”

This hurt, of course, but I tried to suck it up. I didn’t realize it then, of course, but my mother was bouncing between extreme rage and extreme depression. “That son of a bitch gets rich and I’ve got to beg for every little morsel!” she shouted. “How am I going to manage with you underfoot all the time?”

Okay. That was it. My mother was struggling to succeed, and the only thing standing in her way was me, her daughter. The solution was self-evident. I would kill myself! She would mourn for a month or two, then she’d get over it, quickly, and go on to become a huge success.

But how to kill myself?

Then I remembered watching a TV movie where someone slapped a plastic bag over another person’s head and held it there until they died. Suffocation! Perfect. Who says TV isn’t educational?

You hate me! I know you hate me! I asked my mother, hoping that I didn’t have to go through with the plan.

She just looked at me, shaking her head, and said nothing.

That was all the confirmation I needed. I went into the kitchen, found a plastic bag, and put it over my head.

About ten seconds into it, while I was still breathing without difficulty, my mother walked into the kitchen.

“What do you think you’re doing?”

I was going to answer, but I had a bag over my head, and I didn’t think a girl trying to kill herself should try to make casual conversation.

“So you’re trying to kill yourself, huh? Good. Let me call the suicide hot line.”

I just shrugged, still not speaking.

“Rain, did you hear me? Take that fucking plastic bag off your head! If you don’t take it off at the count of three, I’m going to call the suicide hot line. One. Two. Three. Okay, that’s it!”

As I watched, still breathing regularly—I began to suspect that the bag was full of holes—she picked up the phone, found the number, and dialed. While she waited for them to pick up, she turned to look at me, seething. “I know what this is, Rain. This is a ploy for attention. Well, you think it’s going to bring your father here, you’re wrong. When are you going to get it through your head? He doesn’t care. He doesn’t care.”

As you might imagine, that made me feel absolutely wonderful.

Someone picked up at the other end. “Hello, suicide hot line? Can you help me? It’s my daughter. She’s put a plastic bag over her head and she’s trying to kill herself, and she’s driving me fucking crazy.”

I took a moment to remove the bag from my head so I could scream at her: “You’re already crazy!”

“Hello?” She looked at the phone in her hand. “What the fuck? Are you kidding me?!” She turned to look at me again, angrier than ever. “They put me on hold! Can you believe this shit! The fucking suicide hot line put me on hold! Rain, take that fucking plastic bag off your head!”

I took the plastic bag off my head, since clearly it wasn’t working, and I screamed at her. “I hate you! I wish you had listened to your parents and given me up for adoption. You ruined my life!”

“Oh yeah? I haven’t even begun to ruin your life!”

I ran out of the kitchen, sobbing, and locked myself in my room, and she didn’t even bother to look in on me. Maybe it was true that my father didn’t care, but at that moment I felt she cared even less than he did. At that moment, I genuinely hated her.

Not long after, I came home from a weekend on Parthenia to find her asleep on the couch. I was worried about her, and I shook her until she woke. “Mom? Mom, are you okay?”

She looked at me, slowly regaining consciousness, and she didn’t exactly seem happy to see me. “So you’re back from your beloved Daddy’s place,” she said. There was an edge in her voice. “How wonderful! I suppose you expect me to entertain you now.”

“No,” I said. “I was just worried about you. You don’t look so hot.”

“Well, you don’t look so hot, either!”

“That’s not what I meant, Mom!”

She proceeded to rail against me for all the trouble I had caused her, and I stood my ground, determined not to cry. I didn’t have any idea what I’d done, but either I was crazy or she was crazy, and I hoped it was her. I remember thinking, She is fucking crazy. She’s as crazy as my dad. How did I score two totally crazy parents?

“Why don’t you just leave me?” she said once. “Why don’t you just move in with your motherfucking father? If you love him so much, why don’t you just forget about me and move in with the bastard?”

“I love you, too, Mom.”

She shot me a dirty look.

“It’s true, Mom. I love you.”

And it was true. I loved them both. For almost ten years, they’d managed to completely mess up my childhood, and I still loved them. It made no sense. Then again, maybe that’s why I loved them.