Early in 1979, when I was ten years old, I saw my father perform for the first time. He was in Long Beach, California, and I was watching from behind a curtain, off to one side of the stage. Until that moment, I never really understood what my father did for a living, and I can’t say I understood everything he was saying, but I certainly saw his power. Yes, that night, watching Richard Pryor strut across the stage, watching him take command of that theater, I finally got it: my daddy didn’t just tell jokes. He told funny stories that dug for deeper truths.

For years, I’d been asking my father to “teach” me some jokes. He was a funny man, and I wanted to be funny, too. But he never taught me any jokes, because it wasn’t about the jokes, and that night in Long Beach I finally began to understand it. Comedy was about connecting with people in places so personal that it actually made them uncomfortable, and then showing the humor in it.

Hell, comedy was hard.

Mamma came to visit not long after. She was tired all the time, slower, shuffling from couch to chair and back again, always looking for a place to park her tired body, and it struck me that she was getting on in years. Daddy noticed it, too, I guess, and he wanted to do something nice for her, and for the family, so he took a bunch of us to Jamaica. Elizabeth came along, as did Deborah, who by this time had forgiven him for emptying his .357 into her car.

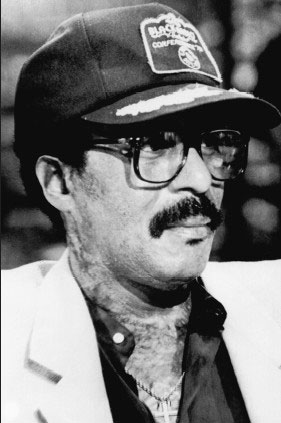

Richard Pryor: Live in Concert (1979)

We took separate flights, though. Daddy had developed this crazy but short-lived notion that he was going to die in a plane crash, and he didn’t want us to die with him, so he got a little neurotic about travel. It was still special, though. The limos. The VIP lounges. The airline employees who escorted us onto the plane as if we were royalty. Man, I miss those days!

We stayed near Kingston, in a big, beautiful airy house with a female chef and female housekeeper, and from the moment we arrived I fell in love with the island. I loved the British accents, which reminded me of Mary Poppins, and I loved the pristine beaches.

On the second day, we were taken on a tour of the old plantation house at Rose Hill, and we heard horror stories about slavery, which made a very deep impression on me.

But by the third day the only thing making an impression on me was my father’s foul mood. It’s as if a black cloud had settled over him all of a sudden, and no one could figure out what it was. (Withdrawal, maybe?) He kept picking fights with Deborah, calling her nasty names—he never hit her though, because this woman knew where to draw the line—and he wandered through the house at all hours, mumbling and cursing at unseen ghosts.

The next night, we were gathered at the dinner table, which was always impeccably set, and Daddy was in such a foul temper that the whole house was tense. One of the young servants emerged from the kitchen and went around the table, setting a hot dinner roll next to each of our plates. When she reached me, I said, “Thank you, Doda,” and a split-second later I felt the back of Daddy’s hand smash into my face. I put my hand to my face and felt blood pouring from my nose, and I immediately burst into tears.

“What did I tell you about disrespecting people?!” Dad bellowed.

“But she asked me to call her ‘Doda,’” I protested, blubbering. “She asked me!”

Doda herself came to my defense, her head bowed, too afraid to look Daddy in the eye. “It’s true, sir. It’s my nickname. All my friends call me Doda.”

“What the fuck is wrong with you people?!” Dad shouted, looking at us as if we were the enemy.

“I didn’t do anything wrong, Daddy!” I repeated, still wailing.

“Don’t you talk back to me, goddamn it! I’m sick of your lip!”

Mamma jumped to my defense. “Now goddamn it, boy—leave the girl alone! You about broke her nose! Junior, help your sister get cleaned up. We can’t have her bleedin’ all over the table.”

My brother led me out of the dining room, and as we moved off we could hear Daddy getting increasingly worked up. Everybody was out to get him. They were playing him for a fool. Couldn’t even trust his own motherfuckin’ family.

He was rambling, paranoid, and he left the dinner table in a huff, cursing everyone in the room, except Mamma, of course. In the morning, the entire incident was forgotten, and we spent our last few days in Jamaica like a normal, happy, well-adjusted family. Hell, we’d practically turned white.

Shortly after we got back, though, Deborah disappeared from our lives. This struck me as odd, because we all liked her, but by this time he seemed to have developed an active interest in Jennifer Lee. From the moment Deborah left, Jennifer was more girlfriend than employee, and I can tell you I wasn’t very happy about it. I didn’t like Jennifer, and she liked me even less.

Daddy must have really loved her, though, because he would beat the shit out of her, and she must have really loved him—because she always took it.

That same year, 1979, Mamma died. Daddy was beside himself. His own mother had died years earlier, and I’m sure it affected him, but his real bond was with Mamma. She was his rock, the one person in his life he trusted beyond all others, and now she was gone.

He took Elizabeth and me back to Peoria for the funeral. Jennifer didn’t go. I imagine she was invited, but a few days earlier he had beat her again, and she had decided to move out.

The funeral was a very sad affair. Mostly I remember Daddy sitting in the front pew, next to me, his head bowed, tears streaming down his face and spilling onto his shiny new pants. The reverend was delivering a long eulogy, about what a fine woman Mamma had been, a real pillar of the community, and I guess that must have made the whores feel pretty good.

When it was over, Daddy went back to the coffin to say goodbye to Mamma one last time, and he collapsed. He had to be carried out, which was scary for us little girls, and it took him awhile to recover. Now that I think of it, though, I’m not sure he ever recovered.

The following day, we flew back to Los Angeles. Daddy was a broken man, and he must have felt he had nothing to look forward to. “I can’t go on,” he told us, which was probably the wrong thing to do, since we were both young girls, but I guess he needed to tell someone, and we were handy. “I just don’t see how I can go on. Nothing means shit no more.”

He recovered, more or less, and that Christmas we went to Hawaii for the very first time. We flew to Honolulu, first class, as always, and then we took a private jet to Maui. Dad was apparently over his paranoia about dying in a plane crash, and sat in the copilot’s seat and asked the pilot a lot of questions. That was one way to get over his fear.

We stayed in a luxurious house that was part of the Hotel Hana Maui, one of the nicest resorts on the island, and the only glitch was Jennifer: she’d come crawling back, and Daddy had invited her along.

Despite her presence, the trip got off to a very nice start. Daddy took us fishing, he spent a lot of time at the beach with us, and he was in fine spirits. I think he was working really hard at getting over Mamma’s passing.

We loved to spend time together in Hawaii. Hana Maui was the one place where Dad could be himself and we could be his kids.

One time he swam out really far, and we kept shouting at him to come back, because he was making us nervous, but he kept waving and going farther out, until he was no more than a tiny black dot with a wet Afro. When he finally got back to shore, he collapsed on the beach, exhausted, and lay there for a while, trying to catch his breath. “What is wrong with you motherfuckers!” he said, half laughing. “Couldn’t you see I was drowning out there! Couldn’t you hear me calling for help!”

The people on the island loved Daddy, and he showed his love for them by writing a big check to help one of the local schools, then topped it off by buying Christmas presents for all of the kids.

Even Jennifer was in a good mood that Christmas, and my feelings for her began to change.

What I didn’t realize then—what no one realized, I guess—is that Daddy was in a deep depression, sparked, no doubt, by the death of his beloved Mamma.

The depression worsened, and on June 1, 1980, all hell broke loose. As you’ve probably guessed, I’m talking about the freebasing accident, which turned out not to be such an accident after all.

The first news reports noted that my father had been smoking crack cocaine, and that he accidentally set himself on fire. But the truth turned out to be much simpler. He was in some kind of psychotic state, induced by a combination of depression and drugs, and the man poured a bottle of rum over himself and struck a match.

The great irony is that my father was at the peak of his fame at the time. He was very proud of the fact that a man with no education, raised in a whorehouse, had become the best known comic in America, and that—as the newspapers never tired of pointing out—he was the highest paid black entertainer in America.

Despite his success, though, Richard Franklin Lennox Thomas Pryor felt like killing himself. His Mamma had just died. She was eighty-nine, so you’d think he would have been prepared for it, but he simply couldn’t get over her passing. He felt ambushed by grief, lost, unmoored, heartbroken, devastated. Mamma had been the dominant force in his life, and his only close relationship since her passing seemed to be with cocaine. Even Jennifer Lee was no longer at his side. She had been beaten so often, and so ferociously, that shortly after we returned from Hawaii she left and swore never to return.

The day of Daddy’s so-called accident was easy enough to piece together. He had been partying that day, as usual, with friends, including his old football buddy and fellow actor, Jim Brown. For a while, everything was going smoothly. The men were swapping stories, telling tall tales, and sharing laughs. At one point, though, Daddy started sinking into one of his depressive rages—rages that were fueled by drug use, and which were becoming increasingly frequent—and he retired from the party.

A short while later, Jim went looking for him and found the door to his bedroom locked. He knocked a few times, but Daddy didn’t answer, and Jim figured he had passed out for the night, which wasn’t all that unusual for him.

But the fact is—as I learned later, from my father himself—Daddy was falling apart. He was in his room at the time, behind locked doors, pacing, much as he did on stage, taking hits from the bottle of rum in his left hand, and talking to Mamma. Yeah, that’s right. He’d been talking to Mamma since she’d passed away, and the conversations were getting more and more frequent.

“I’m going to kill myself, Mamma.”

“Why you going to do that, baby?”

“I’m not happy.”

“Where is it written that a man’s got to be happy?”

“I’m fucking everything up, Mamma!”

“Well, that’s a start, boy—at least you know it’s you that’s doin’ it!”

“I’m trying to change things, Mamma. But I can’t. I just want it to end!”

“How can you change things if you dead, baby! It ain’t yo’ time to go?”

“How do you know that?”

“God decides when it’s your time, boy, not you. You hearin’ me? Richard? You listenin’ to me?”

He was listening, or half listening, anyway, but there was someone else in the room with them, and that was Mudbone. Mudbone wasn’t real. Mudbone was an old wino from Tupelo, Mississippi, created by Daddy for his comic routines, and by this time Mudbone was already a big hit with audiences. He was a storyteller, not a jokester. He was a philosopher who tried—with very limited success—to make sense of life’s many mysteries.

And at that moment Mudbone was telling Daddy to end it. The son of a bitch had turned on him. Life made no sense, he said that night in Daddy’s bedroom. Man spends his whole life trying to make sense of things, and in the end it don’t mean shit. Gonna die, anyway. Why prolong the misery?

“Richard?” Mamma said. “Are you listening to me, boy? Put that bottle down and pull yourself together.”

But Daddy wasn’t listening anymore. He was confused. There were too many voices in his head, too much goddamn noise. He looked at the bottle in his hand—it was still half full—and poured what remained over his head. It dripped through his Afro, over his almond-shaped eyes, past his lips, and onto his fine-ass silk shirt. Then he reached for his bong and a rock of cocaine, set the rock in the bowl, and fished his lighter out of his pocket.

It was no accident, people.

My daddy knew exactly what he was doing.

He flicked the lighter, and—poof!—he burst into flames.

Engulfed, he ran from the room, screaming. Ran through the house, still screaming, and ran down the street, still screaming.

The police found him more than a mile from the house, mute with shock, not screaming anymore, the upper half of his body covered in festering burns.

I was with my grandparents that night, in Marina del Rey, oblivious, but word of the incident quickly spread. And of course everyone in his family was notified—ex-wives, ex-girlfriends, current girlfriends, kids, aunts, uncles.

As soon as my mother heard, she raced to the hospital to donate blood, and she sat by his bed till morning, refusing to leave until the doctors assured her that he was going to pull through.

By the time she reached the parking lot, the press was already there, and one of the photographers recognized her. “Hey, Shelley, bring a camera next time,” he said. “A picture of your ex in a hospital bed would fetch serious money.”

“Fuck off,” Mom said, and she climbed into her car and sped away.

Dad, not long after his “revolutionary suicide attempt”

I didn’t know anything about anything, but I eventually found out—when Dad came clean—that the press got it all wrong. He had tried to commit suicide, he told me. The notion that it had been an accident had been created by his management team to protect him from the media.

It’s still hard to get my mind around it. The management team had two choices. One, Mr. Pryor tried to kill himself. Two, Mr. Pryor set himself on fire by accident during a psychotic episode that got out of control after he ingested massive amounts of cocaine and booze.

Which would you choose?

I still knew none of this, of course. All of this came later. At the time, I was at my grandparents’ place, getting ready for bed. And in the morning, while my father was in intensive care, still fighting for his life, I was busy getting ready for school. I had breakfast, Grandpa Herb lit his first cigar of the day, and then he and Bunny and I went downstairs and got in his car.

My grandparents bickered all the way to school, as usual, drowning out the radio, but then the newscaster interrupted the broadcast with an update on Richard Pryor’s condition, and his tone caught our attention. Mr. Pryor remained in the hospital, still in critical condition, but he was expected to survive. He had suffered third-degree burns, mostly to the upper part of his body, and a team of doctors was tending to him.

For a moment, I couldn’t speak, then the words finally came. “Daddy!” I yelled. “My daddy’s in the hospital. My daddy’s hurt. I want to see my daddy.”

I guess Herb and Bunny were in shock themselves. Richard’s marriage to their daughter hadn’t worked out, but they still had feelings for the man.

“Now, honey,” Bunny said, faltering, and turning in her seat to face me. “There’s nothing we can do for him now. He’s in the hospital, just like the reporter said, and it sounds like he’s getting the best possible care.”

“I want to see him!”

“No. That’s not going to happen. You need to go to school, and we’ll deal with all of this at the end of the day.”

When I think back on that morning, it’s hard for me to believe that my grandparents handled it the way they did. I’m sure they thought they were doing the right thing by having me stick to my routine, knowing full well that I would not even have been able to see my father that day. But I was a ten-year-old girl, and I was scared. I needed to be comforted and held. I needed to be told that everything was going to be all right, even if it wasn’t true. Instead, they dropped me off at school and forced me to deal with it on my own.

“Chin up, honey,” Grandma said. “We’ll see you at the end of the day.”

“You hang in there, Rainy,” Grandpa echoed. “Just get through the day and everything’s going to fine.”

They pulled up in front of my grade school, the Beverly Hills Vista. Bunny got out and opened my door and managed a smile. I didn’t even hear what she said. A moment later, they were gone. I found myself standing on the sidewalk, alone, clutching my schoolbooks and my lunchbox and feeling more isolated and abandoned than I’d felt in my entire life.

Hello! Is anybody out there? Does anybody care? Do I even exist?

I watched their car pull away, hoping they would change their minds and turn back, but they kept going and disappeared from sight. I turned and made my way past the manicured lawn, toward the Gothic-style brick building that housed the school, fighting tears. I didn’t have any idea how I was going to make it through the day.

“Your dad is a burnt piece of shit!”

I turned around. It was a kid from my class. A kid I hardly knew. I dropped my books and my lunchbox and jumped the son of a bitch, fists and feet flying. I beat the crap out of the kid and felt good about it, and a moment later—almost like a time-cut in a movie—I found myself in the principal’s office. I was being taken to task for not controlling my emotions. She didn’t say, “We heard about your father. We’re sorry.” She didn’t say, “We know how awful you must feel.” She didn’t say, “We know you’re in horrible pain.” She didn’t say, “Someone should teach that asshole kid to be considerate of other people’s feelings.”

She said, “Young lady, you have to learn to control your emotions.”

I felt like screaming: “Control my emotions! Fuck you! My father is in the hospital. He almost died!”

But instead I said, “Yes ma’am. I’m sorry.”

And all I could think was, Oh, Daddy. Poor Daddy. What happened to my poor daddy?

That night, I stayed with my mother, and she told me everything.

“Is he going to be all right?” I asked.

“He’s going to be fine,” she said.

“Can I see him now?”

“No,” she said. “They’re not going to let you in the hospital.”

I was very upset, of course, but she made up for it by finding a picture of me and putting it in a little frame and promising to take it to my father in the hospital. I looked a little like Mother Teresa in the picture, only darker.

The following day, she took the picture to the hospital and set it next to Daddy’s bed, and for years afterward that same picture remained on my father’s night table, in his room at the house on Parthenia Street.

A few weeks later, Daddy finally went home, and I got to see him, and after that I went to the house as often as possible, to sit with him and keep him company.

One day, his ex-wife Deborah came by to help out—his ex-wives always came through for him, the abuse notwithstanding—and I watched her put vitamin E oil on his burns. I asked him if it hurt, and he said it only hurt a little, and I reached over and began to help. I wasn’t afraid to put oil on his burns. I would do anything in the world to ease my father’s pain.

A few days earlier, Dad had joked about the incident. “It was an accident, baby. I was eating cookies, and I was dipping them in milk, and there was two kinds of milk. And boom! Motherfucking thing exploded. No one ever told me you couldn’t mix two types of milk.”

But this time—sitting there with Deborah, helping her put oil on his burns—Daddy decided to tell me the truth. “I was drunk out of my motherfucking mind,” he said. “Stoned, too. And I was feeling sorry for myself. And I wanted to die. So I set my black ass on fire.”

Not surprisingly, given my father’s fame, the whole country was talking about the incident. On the radio. On television. In the streets.

I remember I was in a therapist’s office not long after it happened, in one of those sitting rooms shared by several doctors, waiting for my mother to get through another wasted hour of psychobabble, when two patients struck up a conversation.

“You hear about Richard Pryor?” the man said.

“Yes,” the woman replied. “You’ve got to be pretty stupid to set yourself on fire.”

“That’s what he gets for being such a junkie,” the man said. “Drugs really mess you up.”

I stood up, furious. “You shut up!” I told the man. “You’re a fucking asshole.”

“And you’re a very rude little girl!” he said, startled by my language. “You shouldn’t be eavesdropping on other people’s conversations, and you shouldn’t talk to people with such disrespect.”

“You shouldn’t talk about people you don’t know with such disrespect.” I shot back. “Richard Pryor is my daddy!”

Then things deteriorated. The man didn’t believe I was Richard Pryor’s daughter, and neither did the woman, and she called me a liar, and my angry screams brought my mother out of her therapist’s inner sanctum.

“What the hell is going on here?” she asked, startled.

“She claims she’s Richard Pryor’s daughter,” the woman said.

“They were making fun of Daddy,” I said, bursting into tears.

Suddenly, Mom went into Ninja-Mother mode: “First of all, motherfuckers, she is Richard Pryor’s daughter. Second, you better fucking apologize or I’ll mess you up but good!”

Needless to say, they apologized.

The next day, when I saw Daddy, I told him what had happened, and he seemed kind of moved. “Thank you for defending me, Rain,” he said.

“I love you, Daddy.”

“And I’ll tell you something else,” he went on. “I’m proud of Shelley. I like the way she went to bat for you, standing up to those honky motherfuckers!”

I smiled. He returned the smile.

“Mothers are very important,” he said. “I didn’t have much of a mother, but I had Mamma, and you know something?” He lowered his voice to a whisper. “I still talk to her all the time.”

“You do?”

“Uh-huh. She’s right here, in my head, and she ain’t going nowhere.”

Years later, when I thought back on that conversation, it occurred to me that Mamma was the only person who had ever really been there for Richard. She had given him the stability that every child craves—she had been his rock and his salvation. I’ve come to believe that Mamma may have been the only woman Daddy ever truly loved and respected.

I don’t pretend to know what was going on in my father’s head—I was just a kid, after all—but I honestly believe that in the weeks and months after the accident he was busy reviewing his life. The way he treated women, as if they were all whores. The sycophants that drank his cognac and ate his food and laughed at his worst jokes. The violent mood swings. The abuse. The narcissism. The near-total neglect of the various children he had sired.

He was a total disaster as a man. But here’s the thing: as a professional—comic, actor, writer—he was a huge success. And I wonder if maybe that’s what got him through the day. He’d be up there, on stage, strutting, making people laugh, and he’d think, Those people love me. How bad can I be?

Maybe a lot of entertainers are like that. You’re always hearing stories about this star or that star—they seem so nice on the big screen, but when the camera isn’t rolling they are absolute monsters. Now, don’t get me wrong—I’m not saying my Daddy was a monster. But I will say this: it was a lot easier to love him if you didn’t know him.

Ask the women in his life. I’ll bet they’ll tell you the same thing. Daddy never got his sorry black ass out of the whorehouses of his childhood. Women were objects to him, without any real value, but they had pussies, and Daddy loved pussy. Unfortunately for him, it was a package deal. Gotta put up with the bitch to get the pussy.

At least until you got tired of it, which is where the whores came in. Now that was one transaction that Daddy could really relate to. Why the fuck beat around the bush, baby? All this talk of I-love-you and show-some-respect and I’m-just-trying-to-make-a-decent-home-for-us, Richard—it’s all bullshit. A man just wants his pussy. And that goes for every man. And any man who tells you different is a motherfucking liar. And women—they all got their price. Some of the most expensive whores I ever met live right here in Hollywood, in big fancy houses, married to men they hate. Now those are some pretty smart whores!

I never once saw my Daddy hit a whore. I mean, why would a whore piss him off? A whore was there to fuck. And I know for a fact he respected those whores. I’d hear him talking about them to the hangers-on, between hits on the bong. Whores were honest. They weren’t there because they loved my Daddy, and they didn’t pretend to love my Daddy—they were there to fuck. Come on, Richard! Bust a nut already! I want to get paid and go home. Daddy liked it straight, without bullshit. Paid good money for it, too.

That was life with Richard Pryor. Sex and violence, punctuated by rare moments of family happiness.

It’s called fucking, baby! It’s what we do. It’s all people are good for. And it’s fun!

And wham! Get the fuck out of my life, you motherfucking bitch. I’m sorry I ever married you! I never want to see your fat ugly ass again!

So, yeah, he was misogynistic, mercurial, unpredictable, and violent. But he was also my daddy, and sometimes, when he held me close, I looked into his big sad eyes and I knew he loved me.

And that’s the part I want to remember.

Not the shit.

I want to remember the love.

And here’s the thing: as long as my father didn’t think about it too deeply, he was okay with who he was. Maybe even more than okay. Maybe he even liked himself. But when he thought about it too deeply, as he’d done that horrible night in 1980, it almost killed him. So he tried hard not to think about it.

And of course there were moments when he couldn’t get away from himself, as there are for all of us. During those weeks of recovery after the accident, for example, I could see he was trying hard to make sense of his crazy life. But I’m not sure he learned much, and, if he did, I certainly didn’t see any change.

No. Before long, Daddy went back to who he was, with his roving dick leading the way. He went back to the chaos he’d created—false friends, ex-wives, children he didn’t have enough time for, and his whores—always his whores. And he made it work. He made it work because no matter whom he’d hurt or how badly he’d done it, Richard Pryor always forgave himself. It was a neat trick. If he forgave himself, you had to forgive him too. If he could live with it, you had to learn to live with it, too.

It’s history, baby. It happened but it’s over. That was another me.

And it worked every goddamn time, because a little something came with it: money. That’s right, money made everything possible.

In 1983, Daddy signed a five-year contract with Columbia Pictures worth between twenty and forty million dollars, depending on whom you listen to. He was quoted as saying, “I live in racist America and I’m uneducated, yet a lot of people love me and like what I do, and I can make a living from it. You can’t do much better than that.”

That money bought him hookers and starlets and personal trainers and chefs and psychics and dozens of women, always the women.

And he was fine with it.

Because my dad was still carrying that whorehouse on his back.

Everything in life—everything—is a transaction.

It pains me to say this, but when I look back at his life, I don’t think Richard ever had one true friend. He paid for his entourage because he needed it. Daddy did not like being alone. When you’re alone, you think, and when you think your mind might take you to places you’d rather not visit. You might learn something about yourself, and there’s a good chance you won’t like it. So no sir, I’ll take the unexamined life any day!

Too bad he couldn’t have been a little more like Mudbone, his wino alter ego. Mudbone had an almost magical ability to cut through the bullshit of everyday life, to tell it like it was. But Mudbone also knew that people couldn’t handle the truth. And neither can I, I guess. The truth is, my father never earned my love, but I loved him anyway. And after his “accident” I loved him even more—loved him so much that I felt that I had failed him. If I love him enough, maybe he’ll never want to die again. If I love him strong and pure, I can save my daddy’s life.