Richard Pryor doled out a lot of crap in his life, especially where women were concerned, but somehow his ex-wives and his ex-girlfriends and his sometime-flings always forgave him, and a number of them formed this weird sort of Richard Pryor Fan Club.

There were many trips—notably to Maui—where ex-wives and ex-girlfriends were invited to come along with their children. They were generally housed in the same hotel, on the same floor, if possible, and they would sit around sharing war stories and laughing at the memories, though I know some of them were pretty goddamn painful. I think the women in Richard’s life took solace from these joint vacations. Years later, I imagined them forming some kind of support group that would meet once a week in the basement of a local church. As you entered, you would see two signs: AA, Room 111. Former Wives of Richard Pryor, Room 113.

It was a pretty crazy family, and no one ever bothered to explain the entire cast of characters. Some years ago, though, I asked my half sister Elizabeth to help me work out how we were all related, and we came up with this:

Daddy was married seven times to five different women, and he had seven children—seven we know of, anyway. The wives were

PATRICIA PRICE, 1960 to 1961. One child, Richard Jr.

SHELLEY BONIS, 1967 to 1969. One child, Rain.

DEBORAH McGUIRE, 1977 to 1979. No children.

JENNIFER LEE, married for fourteen days in 1981, and, according to Jennifer, again in June 2001, until his death. No children.

FLYNN BELAINE, 1986 to 1987, and again from 1990 to 1991. Two children, Steven and Kelsey.

As my father once said, “I believe in the institution of marriage, and I intend to keep trying till I get it right.”

Then there was another child, Renee, who predated all of us, and who may or may not have been Daddy’s daughter, and there was of course my closest sib, Elizabeth, who was the daughter of Maxine, another nice Jewish girl, like my mom, but one who had the good sense not to marry Richard.

Last but not least, there was Franklin, who came along at about the same time Kelsey was born, but to a different mother. Way to go, Dad!

Elizabeth and I joke that we’re the only ones who know what it’s like to be the half-Jewish daughter of Richard Pryor.

Sad to say, every single one of his wives accused Richard at one point or another—and often more than once—of domestic abuse. But Daddy was either made of Teflon or very good at talking his way out of trouble: the charges never stuck.

In 1986, my final year in high school, the same year Daddy married Flynn, the same year he shot Critical Condition with Gene Wilder, my daddy got sick. He began getting headaches after sex, and it bothered him enough to have it checked out. I’m sure if it hadn’t been related to sex, Daddy would have ignored the symptoms until they literally felled him, but sex was sacred territory, and something needed to be done.

Doctors put him through the usual battery of tests, and they discovered some scarring in portions of Daddy’s brain. They broke the bad news. He had multiple sclerosis. The doctors explained that MS was an autoimmune disease in which the body attacks its own nerve cells, destroying the protective sheath around each nerve and making it impossible for the cells to communicate.

Daddy listened, and he shared the bad news with us, but none of us really understood it. He had occasional headaches, yes, but in every other respect he was the picture of health. We didn’t think it could be all that serious. Plus, as the doctors had told him, the disease was progressive, and it progressed at different rates in different people.

I remember thinking, Daddy’s going to be just fine.

For a long time, Daddy asked us not to talk about the illness with anyone. He was a Hollywood actor, after all, and if any of the higher-ups in the studio system even suspected that he had a degenerative disease he would have found it impossible to keep working. That’s the town for you—all heart.

“Can’t let these motherfuckers find out or I’m really finished,” he told me.

“Come on,” I said. “These people can’t be that bad.”

“They’re worse than that—worse than you can imagine,” he said. “You got to keep these fools close enough to see the shit they’re up to, and far enough so they never see the real you.”

As the disease progressed, though, he couldn’t hide it anymore, and a handful of his classier friends came by to visit—Arsenio Hall is one of the few I can remember. Others sent cards with the usual good wishes. The vast majority, however, did absolutely nothing. Just like the town—they were all heart.

There were plenty of people around the house, though, ready and eager to help. Flynn was there, and Deborah visited regularly, and for a long period I was there almost every day.

Watching my father get worse was absolutely terrifying, and I dealt with it by trying to learn everything I could about the disease. As his doctor had told him, it affected the nervous system, attacking the nerve fibers that allowed the brain to communicate with the rest of his body. In time, Daddy could expect endless misery, which would manifest itself in myriad ways—numbness, tingling, muscle weakness, spasticity, cramps, pain, blurred or double vision, muscle weakness, blindness, incontinence, slurred speech, loss of sexual function, loss of balance, nausea, depression, short-term memory problems, trouble swallowing, even trouble breathing.

There were several types of MS, and some forms were apparently pretty benign, but it was clear that Daddy didn’t have one of those. He was in trouble. He knew it, and we knew it.

Worse still, as I discovered, there was virtually nothing anyone could do for him. Researchers were working on finding a cure, and they were making progress, but not enough to give us hope.

When high school finally ended, I actually moved in with Dad and Flynn. Mom and I were again having trouble getting along, to put it mildly, and it just seemed like the smart thing to do. Plus they liked having me there, especially when I made myself useful as a babysitter. And I liked being there—it made me feel that I was watching over Daddy.

I also went to visit my grandparents from time to time. Grandpa Herb would take me sailing on his little sailboat, Rainflower, and we’d return to the house just in time for dinner. Grandma Bunny cooked these elaborate, multicourse meals, and she always shared her secret recipes with me. “I give them to other people,” she confided. “But sometimes, if they’re not so nice, I leave out a key ingredient.”

At my high school senior luncheon with Mom and Grandma

I had my own life, of course, and I was eager to get my acting career off the ground, so two or three times a week I’d race off to some audition or other, hoping to be discovered—like ten thousand other equally naive young ladies. At one of these auditions, I met Ronnie Yeskel, who was already on her way to fame as a casting director, and she introduced me to Josh Schiowitz, who was both a playwright and a theatrical agent. Josh got me an audition for Head of the Class, a hit television show, and I nailed the audition.

For many years, I had been creating characters in my head, partly as an acting exercise, and partly for my own entertainment. One of the characters was a pseudo gangbanger named Wanita, whom I’d based on some of the wannabe tough girls at Beverly Hills High, and I knew her as well as I knew myself. (Or maybe even a little better!)

When I showed up for my audition, I launched into Wanita’s hostile rap routine—I will cap your ass, motherfucker!—and the humor really worked. The producer called that night to offer me a recurring guest spot on the show, as T. J. Jones, but said they were going to rework the character to make her more like Wanita. Needless to say, I was both elated and flattered.

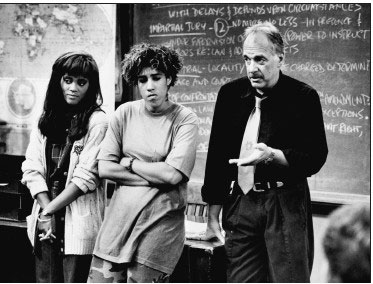

The show, which starred Howard Hesseman, previously of WKRP in Cincinnati, was about a group of high school kids who were too smart for regular classes and, as a result, become isolated in this “brain tank.” Hesseman played the kids’ laid-back history teacher, and when he left the show he was replaced by Billy Connolly, the Scottish comic.

I was a little nervous during the first day of shooting, especially since most of the actors had already been doing the show for three years, but on my very first day, I got a standing ovation from the studio audience, and that changed everything. I was the only member of the cast who had brought the audience to its feet, and I’ll tell you—when I walked off the set, I was as high as I’d ever been. Acting, I realized, could become very addictive.

I really liked my character, too. T. J. was an aggressive, tough-talking girl with a loud, hostile personality, but deep down she was vulnerable and highly intelligent. She reminded me of me a little, of course, because the writers had put a lot of Wanita into her, and playing her came pretty naturally.

With Robin Givens and Howard Hesseman in Head of the Class

I loved the way she talked, and I got plenty of help in that regard from the talented writers. The day T. J. learned she was getting into the brainiac class, for example, she had this to say: “Well, isn’t that a dream come true? Sit in a nice, clean desk with no dirty words carved in it, everyone dressed like it was Easter Sunday, and a teacher who treats you better than your own mama. And a hour later I get sent back to the real world—and that’s the last I see of Disneyland!”

T. J. also rapped pretty good: “Girl in the streets, no clothes and no heat. A crazy outlook, a torn-up book, but she can compete. Girl on fire with her desire seeing stars there and bars there. Should go much higher.”

At the end of my first season, Daddy came to visit the set, and you would have thought Elvis Presley had returned from the grave. He watched us tape an episode, and when it was over the entire staff lined up to meet him and shake his hand. When it was time to go, I walked him back to his car, and he turned to me and said, “You were good, baby. You were real good. Definitely got the stuff.”

It was nice to know he wasn’t the only one who thought so. People magazine called me “Richard Pryor’s funny girl.” They said I had “the same wicked sense of mimicry and humor” as my daddy. I clipped that review and framed it. I remember thinking, Girl, you are on your way!

They say power corrupts, and I wouldn’t know, because I’ve never had much power. But I had a little success that first year, and I can tell you unequivocally that success can also be pretty tricky. I had money in my pocket, and I felt invincible, and people who feel invincible can do pretty stupid things. Like drinking. And drugs. And acting way tougher than they are.

I found myself turning into a version of T. J. Jones, without the soft inside, and without the brains. But somehow, despite my foolish ways, I made it through two seasons on the show without any major fuckups.

I also went out and did what a lot of foolish young actresses do—I got myself a new pair of tits. It’s kind of sad, really. I had a boyfriend at the time who talked me into it, but he didn’t stick around to enjoy them.

Despite my foolishness, I did have one intelligent, adult thought. I was a big girl now, making real money, and I decided I should buy a home. I was also getting a little help from Daddy, who had set up a modest trust fund for me. The money wasn’t enough to live on, certainly, but it was gravy—and it was certainly appreciated.

A couple of months after making this monumental decision, I found a house I liked in nearby Toluca Lake. I needed $100,000 for the down payment, however, and I went to Daddy, who assured me it would be no problem. In the end, though, for reasons I couldn’t understand, he decided that he could only give me $10,000. Since I’d already made an offer on the place, and since my offer had already been accepted, I went through with the deal, and it was a struggle just to make the mortgage every month.

When my gig on Head of the Class came to an end, I was unable to make the payments, so I rented the house to a family. Unfortunately, I didn’t bother to check their references, and they turned out to be professional con artists. This so-called family would move from house to house, refuse to pay rent, and wait for the owners to default on their mortgages, then snap up the property at auction and sell it for a quick profit.

I fell for the scam. Within six months, I’d lost the house and every penny I’d put into it. (I also lost my Porsche, which I wasn’t going to mention, but in the interest of full disclosure I will tell you that it was one of the dumbest purchases of my life. You want to know why I bought the Porsche? Because Robin Givens had one just like it. Smart, huh?)

Meanwhile, I was living with a boyfriend from hell, one of several, and I dealt with my unhappiness—and my lack of employment—by drinking more heavily and doing more drugs. I kept it under control, though, because I had to look all bright-eyed for my auditions.

Eventually, I managed to get a guest spot on Kids, Incorporated, a children’s show, and I also got the lead in Frog Girl, an ABC After School Special. It was about a girl who refused to dissect a frog in biology class and how her decision resonated through the community. It was not a great movie. One reviewer described it as follows: “This is the total dregs of the pretentious, morally patronizing ‘let’s deal with a controversial social issue in a very melodramatic way’ style of television movie.”

I was crushed, but not destroyed.

My next job took me all the way to San Diego, where I got a small part in a production of the rock opera Tommy. I was an understudy, alas, and never got a chance to strut my stuff. When I got back to L.A., one of my high school teachers cast me in a short film, Black Bird Fly, as a girl who gets molested by her father. The father was played by Garrett Morris, who’d made a name for himself on Saturday Night Live, and Whoopi Goldberg played the teacher who eventually comes to my aid. The film got excellent reviews, and even won some kind of award, but I don’t believe it was ever released theatrically.

Suddenly, Rain Pryor was unemployed all over again.

As my self-esteem suffered, I developed a fear of auditioning, mostly because every time I auditioned my self-esteem took another beating. You’re very talented, but not right for the part. You’re very good, but we want a different look. You can act, but the character we have in mind is more attractive.

They all noticed my tits, though, and I noticed them noticing, but nice tits didn’t make me right for the part. I remember auditioning for the role of Aida, Verdi’s famous opera, and being told by the casting director, “Honey, the role is for a black woman.”

So, again, I wasn’t black enough. Or Jewish enough. Or tall enough. Or short enough.

The weeks turned into months and the months turned into years. One morning, I woke up and realized that I was twenty-three and damn near unemployable, and that my tits weren’t going to get me a job.

I didn’t know what to do with my life. I was directionless, and I was broke, but I was still desperate to be an actor, and I did what a lot of actors do: I refused to consider a job in the real world. Like them, I wasn’t ready to let go of the dream. I didn’t want to take a part-time job to tide me over, because I knew too many people whose part-time jobs had become their full-time lives.

At one point, I met a young director who wanted to stage an avant-garde version of the play Joan of Arc. He thought I was right for the part, but he had no money, so I called Daddy. I was trying to explain why I wanted to do this, and why it was so important to me, and he cut me off. “No sweat, baby,” he said. “How’s twenty thousand dollars sound?”

It sounded motherfucking great!

In return, all Daddy wanted was a front-row seat to the premiere.

My father was never generous with his compliments, but the fact that he was willing to finance the venture said it all: he believed in me. He was willing to bet on my talent. Needless to say, I was over the moon.

I asked my half sister Elizabeth to help produce the play, along with another friend, Pam Goodlow. We worked our asses off, and staged it at the Globe Theatre, in West Hollywood. The Los Angeles Times made it a Pick of the Week, and the reviews were uniformly solid. I was walking on clouds.

And absolutely nothing happened.

That’s the actor’s life. You have a little success early in your career and convince yourself that you’ve got a future. You never stop to think, I’ve got to hang on for the next forty years!

That’s something beginning actors don’t understand: one job does not necessarily lead to another. An acting career is more of a gambling habit than a true career. You get lucky once, and maybe it happens again, but ten years later you’re waiting tables and still looking for the big break. It’s brutal, but you continue to believe, because that’s the only thing that gets you out of bed in the morning.

I believe in the dream.

I was having a hard time believing, though, and I guess it showed.

“Rainy, girl, how you doin’?” It was Daddy.

“About the same. You?”

“Oh, you know me—hanging in.” He always said the same thing. The MS was already beginning to manifest itself in small ways—muscle weakness, loss of some motor skills, numbness, blurred vision—but it hadn’t hit him hard yet. “How’d you like to go for a ride with me and Brandy?” he added.

Brandy was his current girlfriend. I went out to Parthenia Street. Daddy and Brandy and I got into the Rolls Royce, and off we went. We were tooling along Highway 101 when suddenly Dad started yelling, “My leg! My leg! I can’t feel my goddamn leg!”

I started laughing—I thought he was doing one of his routines, just trying to cheer me up—but it soon became apparent that he wasn’t screwing around.

Brandy had the presence of mind to reach over and put her foot on the brake, and helped guide the car onto the shoulder. The three of us sat in complete silence for an entire minute, then Daddy laughed, and we joined in. We laughed till we cried.

Finally, Daddy opened the door and got out, with traffic whizzing past. He was a little unsteady, but he was getting the feeling back in his leg. Slowly, he made his way around the front of the car and approached the passenger door. Brandy slid behind the wheel to make room for him. Daddy got in. “That was pretty goddamn freaky,” he said.

Brandy drove us home in silence. I could see Daddy’s profile from where I was sitting. He looked humiliated and frightened.

As it turned out, he had good reason to be frightened. From that day forth, things took a noticeable turn for the worse. Within months, he had lost some mobility in his legs and in his hands, and before long he was using a cane—at least in private.

Like all actors, however, he believed. He believed he would get better. He believed his body would not betray him.

He believed with such faith that later in the year he went to work on See No Evil, Hear No Evil, with Gene Wilder. I went to visit him on the set, and it was painful to watch. He had trouble walking, and his speech was slurred. He couldn’t even remember his lines, and we’re not talking Shakespeare here, people. Sample dialogue: “I hear prison isn’t so bad if you like it up the butt.”

The disease was really taking its toll, but Daddy didn’t want to believe it was that bad, and I didn’t want to believe it either. I guess I was in denial. I was watching him deteriorate and not seeing it. I was an actor, too, after all, and I would only believe what I needed to believe.

After that shoot, Daddy suffered a heart attack, his second, and had triple bypass surgery. Being sick really pissed him off, but it woke him up, too. He decided he should try to work on his health. Before long, he had hired a personal trainer, and he filled the house with running machines, exercise bikes, and training equipment. I don’t know that he used them much, but they were nice to look at.

I remember Flynn came by to help him out, and she urged him to give up his cigarettes and booze. He cut back some, but only some, and tried to make up for their absence with hookers. Flynn called the hookers for him, and she did it with a sense of humor. “What do I care?” she said. “We’re not married anymore. And do you really think he can still get it up?”

Jennifer Lee also came by, and for a brief period she was actually running the show. I hated the way she was always turning up—a genuinely evil version of the bad penny—but I had no say in the matter, and my father only ever listened to himself and his demons.

One day I arrived at the house to find my father lying in a heap on his bed, motionless, staring at the ceiling. There was a shattered wine glass on the floor, and wine stains halfway up the wall. He’d been in an argument with Jennifer, and it had left him completely depleted. That’s when I first discovered that there’s a huge emotional component to MS—that stress can bring it on with a vengeance. I had never seen my father like that: he looked like an empty shell—a hollowed-out version of his real self.

I went over to the bed and whispered, “Daddy, I can take care of you. Please let me help you.”

He shook his head but didn’t look at me. I didn’t understand it. I was giving him a chance, but he wouldn’t take it.

“Daddy, please let me help you,” I repeated.

“No,” he croaked. “Just leave me here.”

I don’t know why he stayed with Jennifer. Maybe it was the make-up sex. Anyone who has ever been in a volatile relationship will tell you that it doesn’t get much better than make-up sex.

For a time, because of Jennifer, I avoided visiting my father, and during this period she actually managed to drive a wedge between us kids by saying we were only after his money, and that we talked trash about him behind each other’s backs, and before long none of us were speaking.

Then one day—thank you, God!—Jennifer was gone, and two of the ex-wives, Deborah and Flynn, began making regular visits to the house to help. Within a year, though, Daddy was in worse shape than ever, and drinking more than ever, so in 1992 he agreed to do a brief stint at the Sierra Tucson Rehabilitation Center, in Arizona. I went out to visit him on Family Weekend, and he was as emotional as I’d ever seen him.

When we had a moment alone, he turned to me and said, “I’m so sorry, Rainy. I’m sorry I hit you when you were little, and I’m sorry I did drugs in front of you and made you worry so much. I’m sorry about the hookers, too—I’m sorry you had to see that.

And I’m sorry I was always beating women up around you. I wasn’t much of a daddy.”

“That’s true, but you’re the only one I’ve got, so I’m stuck with you.”

He gave me a little Willie Winkie teddy bear as a present. It was kind of odd, because I was a grown woman by then, but I think he was giving it to the little kid in me—the little kid he’d neglected. It was his way of making amends.

A couple of other women made the trip out to see him. One of them was Marilyn, his secretary at the time, and the other was a woman named Tina, who told the hospital staff she was his cousin. She was no cousin—she was a hooker—and I guess having a prostitute around for Family Weekend brought back all sorts of wonderful childhood memories—the good old days, when as a child he’d been surrounded by doting whores.

The man was incorrigible. He was never going to change.

When I got back to Los Angeles, I realized I needed to clean up my act, too. I wasn’t a terribly serious drinker, and I seldom did drugs to excess, so in that sense I wasn’t like my daddy. But I came home feeling scared and lost, for him as well as for me, and I decided that I should try to make some changes.

The fact is, I was still very confused about who and what I was. I didn’t have much of a foundation, and I’d been such a chameleon all my life that I didn’t know where the real me was hiding. My upbringing only further confused me. Whenever I’d been with Herb and Bunny, they’d talk to me about Passover, and about the meaning of Yom Kippur, and Bunny would cry on Fridays, when she lit the candles. When I was with Mom, I heard about the power of crystals, and about the power of meditation, and about the power of mind-control, and about every other harebrained scheme that came down the pike back then.

Daddy’s influence only added to the confusion. At different stages of his life he was a Baptist, a Christian, and a Muslim, but never actually practiced anything they preached. He once told me he believed in some kind of Higher Power, but he’d be damned if he knew what it was. (And it wasn’t being all that good to him lately!)

So, yes, I was a bit of a lost soul. Over the years I had dabbled in a bit of everything. I visited synagogues and churches and Hindu temples. I tried my luck at a Tony Robbins seminar. I took the Course in Miracles. But nothing really worked for me because I didn’t know what I was looking for. I guess I was looking for Some Answers, like the rest of us, but they were elusive.

Finally, I tried a 12-step meeting near my house. I liked the fact that they didn’t pretend to have all the answers, and I especially liked the fact that I was supposed to get through things one day at a time. That worked very well for me. The day I walked out of that first meeting, I felt somehow lighter. If I only had to get through the day, I could manage it. It’s when I thought of my entire goddamn life that things got complicated.

It was a good start. And I left there thinking that I was going to be okay.

Of course, a few meetings into it, when it was my turn to speak, my insecurities brought the chameleon back to life. I wanted to belong. I wanted to be just like all the other people there—I wanted to have the same problems they were having so that they would see me as a kindred spirit and not reject me. To that end, I put my acting skills to good use. These fine people talked about their struggles with alcohol, so I talked about my struggles with alcohol. These fine people talked about blackouts, so I talked about blackouts. These fine people talked about cocaine binges, so I talked about cocaine binges.

It was all bullshit, of course. Bullshit fueled by insecurity. And I feel bad about it now.

In time, though, I came to terms with the bullshit. My problem was quite simple, really. There was no there there. I had no center, no personality, no identity. I had been so emotionally damaged as a child that I wanted to be anything and anyone except the little girl I was, and I had managed to drag those feelings with me into adulthood.

That’s what had turned me into such a chameleon. All my life I just wanted to be loved and embraced, and I worked hard at becoming lovable and embraceable. I had done it in kindergarten, in grade school, and in high school, and I was doing it still. I even did it with the men I dated. If a guy was into heavy metal, I was into heavy metal. If he liked Rollerblading, I loved Rollerblading. And if he wanted to get stoned every night, that was my dream, too—to sit there and get stoned with him, night after night, for the rest of our days. Hell, if it made him like me better, I goddamn lived to get stoned.

The 12-step program didn’t help me stop drinking, and it didn’t help me quit drugs, because the real me didn’t much like drinking and didn’t really care for drugs. But the program helped me in much more significant ways. It taught me to listen to myself. It taught me to look within and sit in the dark with my thoughts and work on getting to know the real me. And you know something? I began to like what I saw.

As a child, I had been made to feel as if I had no value, and I’d been deeply affected by that. But I’d come pretty far on my own, despite all the shit, and that was certainly something to be proud of. I figured the Real Me could probably take me even farther. I really was like a lot of the people in that room. I’d been lost, but I was beginning to find my way.

I kept a notebook, and in the days and weeks ahead, per their suggestions, I recorded my goals:

To enhance myself spiritually

To teach

To advise

To always keep learning

To love

To live

To keep a positive attitude when things appear gray

To let go

To allow myself time

To not judge

Unfortunately, as I was improving, feeling stronger day by day, my father returned from rehab in Tucson and continued to deteriorate.

Elizabeth and I went over with a cake that first weekend, to celebrate his sobriety, but he was back on the bottle within weeks. The man had an iron will, but he used it for all the wrong reasons. He would demand alcohol until the people around him were too afraid to say no. He would demand cigarettes. And would demand whores.

Before long, some of his weak-willed hangers-on were coming over with drugs. Daddy could be very convincing. Do this for me, baby, would you? Just one last time. I’m a sick man. I don’t have much to look forward to. I love you, baby. You are the best thing that ever happened to me.

The man was impossible, but I guess it was part of his charm.

Throughout this entire period, I was still trying to make it as an actor, of course, and I kept telling myself to believe. You gotta have faith, Rain. You don’t have faith, you won’t make it. Rejection is part of the business—maybe even the biggest part of the business. If you don’t believe in yourself you’ll never know what you could have been.

Even when I ended up working with a highway construction crew, holding up the SLOW sign for thirty-five bucks an hour, I believed.

And even when I was sitting on the beach in Venice, with a card table and two folding chairs, doing tarot readings for tourists (with the vast knowledge I’d picked up from Mamma!)—I continued to believe.

And when I got a job answering phones for a psychic hot line, with the least psychic bunch of people I’d ever met in my life, I still couldn’t help myself—I genuinely believed I’d act again. Meanwhile, though, I owed it to my employer to be the best psychic I could be, so I believed I was a psychic. And I was pretty good at it, too. People were sad and depressed and they were paying $3.99 per minute to talk to me, and I honestly wanted to do something for them, so I put everything I could into it. I told them that they were probably not going to win the lottery; that someone was going to offer them a job and that it wasn’t a great job, but that it would lead to better things; that they needed to be honest with the people they loved; and that they had to love their children more than themselves.

I had people crying on the line. I felt good about it, too. If they were going to pay $3.99 a minute, which was about what they’d have to pay for a good therapist, they might as well get some real help.

At the same time, I kept wondering: was this it for me? Had my part-time job become my full-time life?

That same year, 1993, while I was worrying about my uncertain future, Dad received a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame. Academy Award–winner Louis Gossett Jr. and composer Quincy Jones were among the hundreds of people in attendance, and both of them spoke at the brief ceremony. Gossett said my father had made it possible for blacks to break into Hollywood, and Quincy Jones described my father as “a pioneer…who made us understand the truth about us.”

It was very emotional for me. The MS was slowly but surely taking its toll, and my father knew his days were numbered, but nobody could take his accomplishments away from him. He was a man who had made a real difference in the world.

Then there was me.

What had I done?

What difference was I making?

Why did I even exist?