[I]t is essential to appreciate the very strong collective ethos of the Internet. From its inception, Internet users have always been passionately in favour of internal control and against outside influence. In effect, for many years the Internet has operated as a fully functioning anarchy.

—Duncan Langford, “Ethics @ the Internet: Bilateral Procedures in Electronic Communication” (1998, 98)

The Challenge: Counterterrorism Online

The Internet and its online platforms provide terrorists with anonymity, low barriers to publication, and low costs of publishing and managing content. The advent of greater user interactivity provided by Web 2.0 and the meteoric rise of social media have enabled radical groups and terrorists to freely disseminate ideas and opinions using such multiple modalities as websites, blogs, forums, and social networking and video-sharing websites. Counterterrorism on the Internet is certainly lingering behind the terrorists’ manipulative use of this medium. Given the growth of Internet research in recent years, it is rather surprising that research into online countermeasures has been overlooked, or at least has not provided efficient strategy and fruitful devices or tactics. According to Jody Westby (2006), several factors combine to explain this research gap: (1) difficulties in tracking and tracing cyber communications; (2) the lack of globally accepted processes and procedures for the investigation of cybercrimes and cyberterrorism; and (3) inadequate or ineffective information sharing systems between the public and private sectors, between governments, and between counterterrorism agencies. Although there are technological reasons that increase the difficulty of tracking and monitoring online terrorist traffic, the problem rests largely with the legal domain: governments around the globe must address these critical issues through legal frameworks and policy directives that advance information security and improve the detection and prosecution of cyberterrorists.

The virtual war between terrorists and counterterrorism forces and agencies is certainly vital, dynamic, and ferocious. The National Security Agency, Department of Defense, Central Intelligence Agency, Federal Bureau of Investigation, Defense Intelligence Agency, other US and foreign intelligence agencies, and some private contractors have been fighting back: cracking terrorist passwords, monitoring suspicious websites (and cyber-attacking others), and planting bogus information. Interest in countering online terrorism has also brought together researchers from around the world and from various disciplines, including psychology, security, communications, and computer sciences, to develop tools and techniques to respond to the challenge (Sinai 2011). It has spawned an interdisciplinary research area—intelligence and security informatics—which studies the development and use of advanced information technologies and systems for national, international, and societal security-related applications. However, as some security and terrorism experts such as Bruce Hoffman argue, there could be better ways to counter the threat: “The government efforts are inadequate. The private sector is doing a better job than the government. Our enemies have embraced the Internet. We have to ask how closely the government is monitoring it” (quoted in Blumenthal 2007).

Recognizing the online threat, the White House’s counter-radicalization strategy, published in August 2011, acknowledged “the important role the Internet and social networking sites play in advancing violent extremist narratives” (The White House 2011a, 6). The strategy’s implementation plan, which came out in December 2011, stated that “the Internet has become an increasingly potent element in radicalization to violence” and that new “programs and initiatives” had to be “mindful of the online nature of the threat” (The White House 2011b, 20). Crucially, it also committed the administration to formulate a strategy in its own right: “[B]ecause of the importance of the digital environment, we will develop a separate, more comprehensive strategy for countering and preventing violent extremist online radicalization and leveraging technology to empower community resilience” (The White House 2011b, 20).

However, no such online strategy has yet been published. The Bipartisan Policy Center’s Homeland Security Project, co-chaired by former 9/11 Commissioners Gov. Tom Kean (R-NJ) and Rep. Lee Hamilton (D-IN), released a report in December 2012, Countering Online Radicalization in America, that identified the shortcomings in US online counter-radicalization strategy and recommended a path to improvement (Neumann 2012). According to the center’s analysis, approaches aimed at restricting freedom of speech and removing content from the Internet are not only the least desirable strategies, but they are also the least effective. Instead, the government should play a more energetic role in reducing the demand for radicalization and violent extremist messages. Specifically, the center’s report recommended developing a strategy:

• The White House must revise its counter-radicalization strategy in order to make it stronger and more specific; and the White House should begin its implementation with alacrity.

• The strategy should include components designed to reduce the demand for radicalization and violent extremist messages, and exploit the online communications of extremists in order to gain intelligence and gather evidence.

• The government should clarify online law enforcement authorities, and communicate with Internet companies on the nature of radical threats, propaganda, and communication.

• The government should accelerate the establishment of informal partnerships to assist large Internet companies in understanding national security threats as well as trends and patterns in terrorist communications, so that companies become more conscious of emerging threats and key individuals and organizations, and may find it easier to align their takedown efforts with national security priorities.

• The government should work to reduce the demand for radical messages by encouraging civic challenges to extremist narratives through countermessaging efforts by community groups to promote youth awareness and education.

• Counterextremism education for youth should be expanded, along with partnerships to educate parents, teachers, and communities on the signs and risks of extremism. For example, government should encourage school authorities to review and update their curricula on media literacy, consider violent extremism as part of their instruction on child-safety issues, and develop relevant training resources for teachers.

• The government should identify up front what resources will be committed to outreach and education programs, as well as the metrics that will be used to measure success.

• Law enforcement and intelligence agencies need to take better advantage of the Internet to gather intelligence about terrorists’ intentions, networks, plots and operations; and they need to secure evidence that can be used in prosecutions.

• The amount of online training offered to members of law enforcement and intelligence agencies should be increased, including state and local agencies, so they are conscious of the increasingly virtual nature of the threat and can use online resources to gather information about violent extremist communities in their local areas. For example, extremist forums and social networking sites are essential for identifying lone actors, many of whom have a long history of online activism through posting messages in online forums, running blogs, and maintaining Facebook pages. These communications should be monitored to watch for sudden changes in behavior including escalating threats or announcements of specific actions. (Neumann 2012)

Although this list of recommendations may be useful and effective, it does not represent a general strategy or theory. Besides the legal and practical issues involved, online counterterrorism efforts suffer from a lack of strategic thinking. Various measures have been suggested, applied, replaced, changed, and debated, but there has never been an attempt to propose a general model of online counterterrorism strategy. Countering terrorist use of the Internet to further ideological agendas will require a strategic, government-wide (interagency) approach to designing and implementing policies to win the war of ideas. The notion of “noise” in communication theory is suitable as a basic theoretical framework to conceptualize various measures and their applicability.

Noise in Communication Processes

In communication theory, noise is that which distorts the signal on its way from transmitter to recipient. Noise interferes with the communication process, as it keeps the message from being understood and prevents it from achieving its desired effect. It is inevitable that noise distorts the message being sent by getting in the way. The concept of noise was introduced as a concept in communication theory by Claude Shannon and Warren Weaver in the 1940s.

1 They were mostly concerned with mechanical noise, such as the distortion of a voice on the telephone or interference with a television signal that produced “snow” on a television screen. In the succeeding decades, other kinds of noise have been recognized as potentially important problems for communication (Rothwell 2004):

• Physical noise is any external or environmental stimulus that distracts us from receiving the intended message sent by a communicator.

• Semantic noise occurs because of the ambiguities inherent in all languages and other sign systems.

• Cultural noise occurs when the culture or subculture of the audience is so different from that of the sender that the message is understood in a way that the sender might not have anticipated.

• Psychological noise results from preconceived notions we bring to the communication process, such as racial stereotypes, reputations, biases, and assumptions.

Although the concept of noise was first perceived as relevant only to the potential for interfering with the transmission of a message, it later became recognized as a crucial element in the communication process, potentially affecting each stage of the process. Noise can represent physical noise (e.g., loud music, shouting reporters) as well as mental noise such as stress, anxiety, or time constraints that distracts one’s thoughts. Today, noise is used as a metaphor for all the problems associated with effective communication, interfering with every stage of the process (including encoding, decoding, transmitting, and interpreting).

The concept of noise in communication theory and research often has been treated as a negative element, damaging the communication process. In fact, most empirical uses were directed at reducing or minimizing noises to improve the flow of communication. However, today noise is breaking away from the status of undesirable phenomenon bestowed upon it by traditional communications theory. No longer merely an undesirable element to be eradicated so as to retain the purity of the original signal, noise can be regarded as a more complex, even desired element. When considering terrorist (or any other illegal, harming, or dangerous) communication, one may question the instrumentality of creating noise that may reduce the communicator’s efficiency and success. As the following sections illustrate, noise can be employed to harm the flow of information, the decoding of messages, the communicator’s credibility and reputation, the signal’s clarity, the channel’s reach, the receivers’ trust, and other components of terrorist communication. Semantic, psychological, cultural, and physical noises may all be part of a rich variety of countermeasures, which can be organized in a strategic framework. Thus, noise could become a key conceptual and theoretical foundation in the strategy of countering terrorism online (Aly, Weimann-Saks, and Weimann 2014).

Conceptualizing the Notion of Noise into a Strategy

Strategic communication planning is one of the most neglected areas of counterterrorism, especially when it comes to the disruption of terrorist communication (Bolz, Dudonis, and Schulz 2002; Halloran 2007). Strategic communication requires a sophisticated method that maps perceptions and influences networks, identifies policy priorities, formulates objectives, focuses on “doable tasks,” develops themes and messages, employs relevant channels, leverages new strategic and tactical dynamics, and monitors success. This approach has to build on in-depth knowledge of radical thinking, radicalization processes, and factors that motivate radical or terrorist behavior. A successful approach will have to combine hard and soft power in terms of strategic communication (Nye 2004a). The principal understanding of power—to make others do what you want or produce the outcomes you want—has not changed. Although hard power is the ability to order others to do what you want, Joseph Nye (2004b) defines soft power as “the ability to get what you want through attraction rather than coercion or payments.” As Nye (2004b, 256) explains: “When you can get others to want what you want, you do not have to spend as much on sticks and carrots to move them in your direction. Hard power, the ability to coerce, grows out of a country’s military and economic might. Soft power arises from the attractiveness of a country’s culture, political ideals, and policies.”

An effective communication strategy to counter online terrorist activities has to combine both hard power elements (such as hacking) and soft power elements (such as psychological warfare), because “soft power and hard power can reinforce each other; one is not contrary to each other” (Nye 2003, 46). Nye (2003) also assumes that soft power does not increase relative power on the hard side, but it does make hard power more acceptable, lowering the costs of exercising such power. Returning to the notion of noise, mechanical noise includes the elements of “hard power,” whereas social and psychological noise both require a “soft power” approach. A successful application of “noise” as a counterstrategy against terrorists’ appeal on the Internet will need to incorporate the following elements:

• Credibility: As in other communication processes, a key factor in determining the persuasiveness of terrorist messages is the credibility of the source. Thus, a counterstrategy may involve systematically damaging the credibility of the terrorist authority while introducing an alternative authoritative or credible source. Previous studies of the inner debates and disputes among terrorists online may expose cleavages and splits that can be used to attack the credibility of online terrorist authorities (Weimann 2006c, 2009d).

• Terminology: Terminology plays a significant role in the process. For example, a better understanding of the nuances of Islam (in contrast to extreme Islamic preaching), the nuances of jihad, Salafist terminology, and the subtexts of their communication will be required. Effective application of “noise” may rely on the use of key terms, exposing their manipulative uses, relating new meaning to them, or weakening their conventional usage. For instance, should the terms “jihad” and “jihadist” be replaced with their nonviolent interpretations, provided by leading Muslim figures? The term “Islamism” may be replaced with the term “anti-Islam,” suggesting that it is far from being in line with the pure and original values of Islam.

•

Traditions: The rhetoric of online preaching and radicalization relies on traditions. Thus, solutions should come from within Muslim traditions, because solutions derived from Western traditions will by definition be rejected as illegitimate. This approach requires a deep understanding of the traditional thinking, values, and symbols of the community targeted.

• Partners: To be truly effective in delegitimizing radical appeals and attraction, the countercampaign may involve the activation of “partners” who come from within the targeted community. Thus, the alternative voices, suggesting alternative narrative and discourse, should come from within Muslim religious leadership, not from the West.

• “Think global, act local”: A long-term perspective starts with the search for additional “agents” of change in supporting actors and institutions. Such actors may include state institutions that provide education, medical treatment, and social warfare. Furthermore, universities in the Arab world (as well as schools and nongovernmental organizations) could provide useful venues in which to open up the “modernization” debate. The same debate can be continued through Islamic education in public schools throughout Europe, articles in journals, and the efforts of individual intellectuals. Such debate would allow all parties to hear different views and engage in a discussion that can truly educate, without appearing to be a narrowly construed propaganda effort from the start. Again, these educational reforms need to come from within the Muslim world, although the West can support it with its resources (Von Knop and Weimann 2008, 891–92).

An effective strategy must be multifaceted, addressing all of these aspects. It will be a long-term undertaking that must be based on familiarity with the targets’ background, mentality, values, beliefs, history, frustrations, and hopes. Moreover, before such a communication strategy can be developed, it is essential to define the strategic goals, identify potential partners, and characterize the target audiences. As one US counterterrorism official explained, the problem is “that we focus on the terrorists and very little on how they are created. If you looked at all the resources of the US government, we spent 85–90 percent on current terrorists, not on how people are radicalized” (quoted in deYoung 2006).

The first step in this process involves identifying terrorists’ online platforms and studying their contents to determine the necessity of applying various disruptive tactics. This monitoring can be done by human analysts and coders (i.e., the manual approach) or by automatic web crawlers. The manual approach is often used when the relevance and quality of information from websites are of the utmost importance; however, it is labor-intensive and time-consuming, and often leads to inconclusive results. The automatic web-crawling technique is an efficient way to collect large amounts of web pages. Crosslingual information retrieval can help break language barriers by allowing users to retrieve documents in foreign languages through queries in their native languages.

The monitoring process will have to cover both websites and social media, from forums and chatrooms to Facebook, Twitter, Youtube, and Instagram. Observation is essential to learn about the target groups, participants, key players, appeals and rhetorical motives, and ideas and rewards promised. The information gathered at this stage may indicate what measures are required, if any, and the urgency for applying noise tactics. The following illustrative examples of actual “noise” will distinguish between mechanical and technological noises and psychological and social noises.

Applying Noise

Mechanical and Technological Noises

These types of noise refer to the technological disruption of the flow of communication. Mechanical and technological tactics include a rich variety of interventions, from damaging websites and defacing and redirecting their users to spreading viruses and worms, blocking access, hacking, and total destruction. These deviant measures can be adopted and used against online terror in order to minimize its reach and impact. In the most severe cases, hacking the websites may be the most extreme measure, though in the long run it is not always the most efficient one. Ross Anderson (2008) describes an impressive arsenal of common hacking techniques, all of which counterterrorism strategies can employ. Many actual attacks, Anderson argues, involve combinations of vulnerabilities. Anderson’s list of “the top 10 vulnerabilities” suggests a hacking strategy using each of these vulnerabilities (2008, 368). Most of the exploits make use of program bugs, of which the majority is stack overflow vulnerabilities. (These vulnerabilities are flaws in program coding that can make a program crash if too much data is forced onto it, as a hacker might attempt to do.) Anderson also argues that none of these attacks can be stopped by encryption, and not all of them are stopped by firewalls.

Such disruptive counterattacks on terrorist online platforms are not new. In May 2012, Secretary of State Hillary Clinton revealed that the US government had intruded on al-Qaeda websites in an effort to counter the terrorist group’s activities (Hudson 2012). This revelation showed not only that the fight against terror continues unabated, but also that much of the battle is taking place online. According to Secretary Clinton, State Department cyber-experts targeted tribal websites in Yemen. The intruders took down the ads that al-Qaeda had put up on these sites, which bragged about killing Americans, and uploaded their own counter-ads, which exposed the ruthless coercive methods that al-Qaeda has used on Yemenis. Numerous states, including France, Germany, Israel, Italy, the Netherlands, Russia, and the United Kingdom, have launched similar destructive and disruptive attacks. However, such attacks have had very limited effect, since the terrorists have easily managed to reestablish their online platforms and reemerge in cyberspace.

A more sophisticated form of “mechanical noise” is the optional use of Trojan horses, viruses, and worms against terrorists. The common distinction among the three is that a Trojan horse is a program that does something malicious when run by an unsuspecting user; a worm is a program that replicates itself in order to spread to other computers; and a virus is a worm that replicates by attaching itself to other programs (Anderson 2008). A virus or a worm will typically have two components: a replication mechanism and a payload. The replication mechanism enables the virus or worm to make a copy of itself somewhere else, usually by breaking into another system or by mailing itself as an attachment. The payload—which usually is activated by a trigger, such as a specific date—may then inflict one or more of these damages: make selective or random changes to the computer’s protection; make selective or random changes to user data (e.g., trash the disk); lock the network (e.g., by replicating at maximum speed); steal resources or steal data; and even take over the infected system.

One further form of this type of noise is identity theft. Terrorists use this crime to fund their activities and disguise the identities of their operatives. For example, the al-Qaeda terrorists involved in the 9/11 attacks had opened 14 bank accounts using several different names, all of which were fake or stolen. If criminals can steal someone’s identity, counterterrorists can do the same. Using identity theft tactics, a video or audio recording could be produced and placed on al-Qaeda websites. Such attacks can create confusion among the terrorists’ followers and supporters, harm the credibility of their websites and messages, and lower these sites’ exposure and attraction.

Such actions require the skills and experience of hackers. Indeed, hackers have been secretly recruited and used for counterterrorist attacks. In September 2013, the British government officially admitted such practices: it announced the establishment of the Joint Cyber Reserve Unit. Under the £500 million initiative, the British Ministry of Defence would recruit hundreds of reservists as computer experts to work alongside regular armed forces. The unit was formed to defend national security by safeguarding computer networks and vital data, and also to launch strikes in cyberspace if necessary. The head of the new unit declared that convicted computer hackers could be recruited to the special force if they pass security vetting (BBC 2013). Many companies and security agencies are also recruiting hackers, either to play the “red team” in simulations of cyberattacks, or to suggest and launch counterattacks. The well-regarded Mandiant Corporation, which uncovered a series of cyberattacks on US networks by a branch of China’s People’s Liberation Army, was also hired by the

New York Times and the

Wall Street Journal when they were hacked. Mandiant’s professional hackers also consult with a number of Fortune 500 companies at a reported rate of $450 an hour (Mulrine 2013). The US military is also reaching out to even younger students through high school talent searches in the form of cyber-games like CyberPatriot, a hacking tournament that pits young high school students against industry mentors (who play the aggressors) in a contest to see who can destroy the other’s network first (Mulrine 2013).

In the new cyberspace battlefield, there is a real need for new warriors: the cyberwarriors. As John Arquilla, a professor of defense analysis at the US Naval Postgraduate School in Monterey, and the man who coined the term “cyberwarfare” argued,

Instead of prosecuting elite computer hackers, the US government should recruit them to launch cyber-attacks against Islamist terrorists and other foes. The brilliance of hacking experts could be put to use on behalf of the US in the same way as German rocket scientists were enlisted after the second world war … the US had fallen behind in the cyber race and needed to set up a “new Bletchley Park” of computer whizzes and code-crackers to detect, track, and disrupt enemy networks. If this was being done, the war on terror would be over. (Quoted in Carroll 2012)

Applying Psychological and Social Noises

The tactics included in this category involve various psychological and social operations and counterpropaganda. Psychological and social noises encompass several different terms: information warfare, information operations (IOs), and psychological operation (PSYOP). There are numerous definitions of these terms (Denning 1998; Ventre 2009, 2011). Information warfare is the use and management of information technology to pursue a competitive advantage over an opponent. It may involve collecting tactical information, ensuring that existing information is valid, spreading propaganda or disinformation to demoralize or manipulate the enemy and the public, or denying opposing forces the opportunity to collect information or undermining the quality of their information. Information warfare consists of a broad variety of IOs. The focus of IO is on the decision maker and the information environment in order to affect decisionmaking and thinking processes, knowledge, and situational understanding. Thus, for instance, PSYOPs are a part of IOs.

As defined, PSYOPs are operations designed “to convey selected information and indicators to foreign audiences to influence their emotions, motives, objective reasoning, and ultimately the behavior of foreign governments, organizations, groups, and individuals. The purpose … is to induce or reinforce foreign attitudes and behavior favorable to the originator’s objectives” (Joint Chiefs of Staff 2010, G-8). As a communication medium and vehicle of influence, the Internet is a powerful tool for psychological campaigns. Consequently, the realm of military PSYOP must be expanded to include the Internet: “Although current international law restricts many aspects of PSYOP either through ambiguity or noncurrency, there is ample legal room for both the U.S. and others to conduct PSYOP using modern technology and media such as the Internet” (Lungu 2001, 17). Whether used offensively or defensively, it is clear that the Internet is an important tool for PSYOP and can bring tremendous capabilities and informational advantage to forces employing this medium. Given the strategic opportunities afforded by the Internet, there are several options for employing this medium in PSYOP. Counterterrorism agencies in particular could use the Internet offensively to help achieve unconventional warfare objectives, as well as to address and counter adversarial propaganda, disinformation, and incitement. In addition to developing websites with this purpose in mind, preemptive messages and Internet products such as streaming audio and video, online video games, mediated newsgroups, and ad banners can be leveraged for their strategic value and reach. A 2000 Defense Science Board report on PSYOP also suggested some less obvious potential tools that use emerging media technologies, such as chat rooms and instant messaging services that could be used for “guided discussions” to influence how various groups and audiences think about certain topics (quoted in Lungu 2001, 15–16).

Some of these tactics are rooted in the evolving domain of political Internet campaigns.

MoveOn.org is a prominent example of a web-based political campaign, in the form of a public policy action group. In many ways, terrorists launch their online campaigns in the same way legitimate political campaigns use the Internet. Both types of campaign attempt to attract and seduce users by engaging them in a sensory experience, trying to manipulate their needs, suggesting the fulfilment of a goal, and providing a higher-level motivation to inspire and guide them to make a choice. Once the goal is fulfilled and the user is captivated, the function at this point is to form a relational bond between the user and the party, candidate, group, or organization. Online campaigns and countercampaigns in the political arena can therefore provide lessons to be learned and serve as pivotal experiments to guide counterterrorist campaigns.

Political campaigns are in fact a series of actions and appeals involving resource mobilization. The communicators are trying to mobilize the predisposed, demobilize hostile voters, convince the undecided, and convert the initially hostile. They must do so by designing persuasive messages, communicating these messages, monitoring the responses, and facilitating the desired behavior. Campaigning via the interactive Internet often provides social bonding and replicates feelings of personal contact. These elements, which are also frequently found in terrorist websites, also can be used in countercampaigns. However, before such campaigns are launched, the agencies involved should know both the psychographic profiles of those susceptible to recruitment and the messages that affect them. Agencies also need to understand how these individuals are influenced: what channels are meaningful to them, who they listen to, how peer networks affect them, and how to reach them most effectively.

In a January 2014

Los Angeles Times op-ed on “Future Terrorists,” Jane Harman of the Wilson Center argued that “we need to employ the best tools we know of to counter radicalizing messages and to build bridges to the vulnerable.… Narratives can inspire people to do terrible things, or to push back against those extremist voices” (Harman 2014). To run such a strategy, a political Internet campaign against terrorism must use tactics that have proven to be successful and that have counterterrorism applications. Finding such effective tactics was at the heart of discussions at the January 2011 Riyadh Conference on the Use of the Internet to Counter the Appeal of Extremist Violence. Co-hosted by the United Nations Counter-Terrorism Implementation Task Force and the Naif Arab University for Security Sciences in Riyadh in partnership with the Center on Global Counterterrorism Cooperation, the conference brought together around 150 policymakers, experts, and practitioners from the public sector, international organizations, industries, academia, and the media (United Nations Counter-Terrorism Implementation Task Force 2012). The conference focused on identifying good practices in using the Internet to undermine the appeal of terrorism, expose its lack of legitimacy and its negative impact, and undermine the credibility of its messengers. Key themes included the importance of identifying the target audience, crafting effective messages, identifying credible messengers, and using appropriate media to reach vulnerable communities. Among the recommendations were several that relate to psychological/social noises:

• Promote counternarratives through all relevant media channels (online, print, television/radio).

• Make available a counternarrative whenever a new extremist message appears on Facebook, YouTube, or similar outlets.

• Offer rapid counternarratives to political developments (e.g., highlight the absence of al-Qaeda and other extremist groups at popular protests).

• Consider selective take-down of extremist narratives that have the elements of success.

• Ensure that counternarratives include messages of empathy/understanding of political and social conditions facing the target audience, rather than limiting the counternarrative to lecturing or retribution.

• Offer an opportunity for engagement in crafting and delivering counternarratives to young people who mirror the “Internet Brigade” members of al-Qaeda.

• Support the establishment of civil society networks of interested groups, such as women against violent extremism, parents against suicide bombers, or schools against extremism. (United Nations Counter-Terrorism Implementation Task Force 2012, 81)

The M.U.D. Model

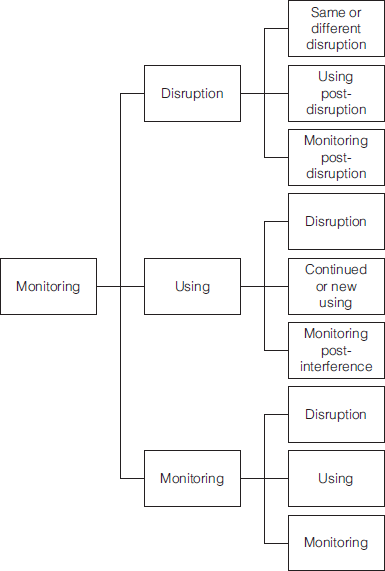

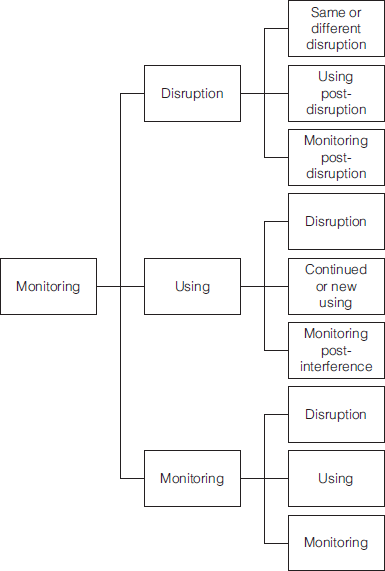

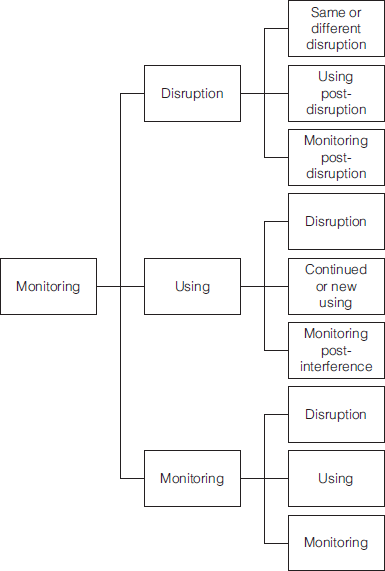

This interference with terrorist online communications may be described by the “M.U.D.” model. This model was presented first at the September 2006 NATO workshop “Hypermedia Seduction for Terrorist Recruiting” held in Eilat, Israel, and then at the October 2007 NATO advanced research workshop “Responses to Cyber Terrorism” held in Ankara, Turkey. The M.U.D. approach (which stands for monitoring, using, and disrupting) is a flexible, multistep model that applies the options of passive surveillance (monitoring), interfering with the traffic and the online contents (using), and finally removing material and blocking access (disrupting) (Sinai 2011, 23–24).

Figure 9.1 presents a visual representation of the M.U.D. model.

First, terrorist websites need to be monitored in order to learn about terrorist mindsets, motives, persuasive “buzzwords,” audiences, operational plans, and potential targets for attack. This form of knowledge discovery refers to nontrivial extraction of implicit, previously unknown and potentially useful knowledge from data. Increasingly, forums, blogs, and other frequently updated sites have become the focus of monitoring attention. Second, counterterrorism organizations need to “use” the terrorist websites to identify and locate their propagandists, chatroom discussion moderators, Internet service provider hosts, operatives, and participating members. The retrieved data need to be archived to enhance the learning process and to identify social networks. A social network consists of a network of connections between people, between people and events, and between people and organizations. Mathematical techniques can be used to identify key persons or clusters of people within a network, optimize the way in which a network is displayed, and measure the network’s robustness. Third, terrorist web-sites and other online platforms such as social media need to be “disrupted” through negative and positive means. In a negative “influence” campaign, sites and postings can be infected with viruses and worms to destroy them, or kept “alive” in order to be flooded with false technical information about weapons systems, rumors intended to create doubt about the reputation and credibility of terrorist leaders, or conflicting messages that can be inserted into discussion forums to confuse operatives and their supporters. In a more positive approach, alternative narratives can be crafted and inserted into the sites to demonstrate the negative results of terrorism or, if targeting potential suicide bombers, to suggest the benefits of the “value of life” versus the self-destructiveness of the “culture of death and martyrdom” (Sinai 2006).

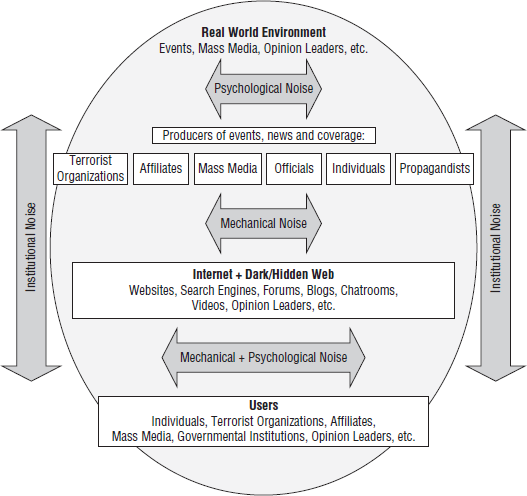

These options are not mutually exclusive. The process of monitoring online contents can lead to a stage of interference that may, in turn, change to a disruptive stage. The model above describes these variations. The concept of “noise” is well integrated into the M.U.D. model, since the various noises (mechanical, psychological, social, and institutional) may be applied in each stage, in varying forms and magnitudes. Various producers present, post, and promote radical message in various forms (videos, lectures, games, postings, online publications, and social media) on the Internet and in the dark web. Target audiences such as potential followers, radicals, terrorist organizations, journalists, governmental agencies, and nongovernmental organizations receive these messages directly or indirectly, through exposure, interpersonal diffusion, or search engines. Greater understanding of this communication process enables counterterrorism proponents to identify potential targets of a counterstrategy or a type of noise. The model in

figure 9.2 presents the terrorist communication process and the placement of various “noises” that may hinder, slow down, damage, or disrupt terrorist abuse on the Internet (Von Knop and Weimann 2008).

No longer merely an undesirable element to be eliminated from communication, noise can be regarded as a more complex and even desired element under certain circumstances. When it comes to terrorist communication, the concept of noise can serve as a key conceptual and theoretical foundation in the strategy of countering terrorism online. As this model demonstrates, various “noises” are useful methods of harming the flow, the decoding, the communicator’s credibility and reputation, the signal’s clarity, the channel’s reach, the receivers’ trust, and more aspects of terrorist messages online. By creating and using mechanical/technological or social/psychological noises, counterterrorism proponents may tap into the potential of a rich variety of countermeasures and help to organize them in a strategic framework.

The notion of noise also relies on using the vulnerabilities of terrorist online activities. Terrorists’ online presence and activities are mostly “visible”; they are open to all. Terrorists are seeking greater exposure and trying to reach vast audiences, particularly when it comes to propaganda, psychological warfare, publicity, and the early stages of the radicalization process. Moreover, the way they invade the Internet and abuse its liberal spirit and unregulated nature leaves them open to intrusions. Such intrusions may and should include efforts to challenge the seductive terrorist narrative with alternative counternarratives.

Source: Von Knop and Weimann 2008, 893.