First find the diopter adjustment and set it at zero.

First find the diopter adjustment and set it at zero.Joseph Hickey once defined bird-watching as a disease “which can be cured only by rising at dawn and sitting in a bog.” That may not be quite true, but why do people watch birds? And once our interest is sparked, what equipment do we need, and how do we go about finding and identifying birds?

Every year I field hundreds of questions about how to watch birds. What are the best binoculars? How do I pick a field guide? Is it best to go birding alone or with a group? I love helping people start bird-watching. After all, no one should go through life listlessly.

Q I’m interested in doing more than just looking at my backyard birds, but isn’t birding an expensive hobby, with state-of-the-art equipment and a lot of travel?

A Birding doesn’t have to be expensive, though it certainly can be for those who purchase the best optics, the most current electronic gadgets, and the airplane tickets to embark on world travel. But it can be equally satisfying, and sometimes even more so, to watch birds while spending very little money. You can have years of enjoyment with excellent binoculars costing less than $300 that will allow you to see and identify as many birds as those top-of-the-line ones. Investing $30 in a field guide can provide a lifelong reference for learning about hundreds of birds in your own area and anywhere else you may go in North America. And birding locally can provide endless enjoyment and excitement as you hone your skills and continually learn more about the diversity and behavior of birds.

Q My husband bought me a really great pair of binoculars, but whenever I try to look through them, everything sort of blacks out and I can’t see a thing!

A Considering how expensive binoculars can be, it’s odd that most companies don’t include operating instructions in the package. Using binoculars is like riding a bike — wonderfully easy, once you have the hang of it.

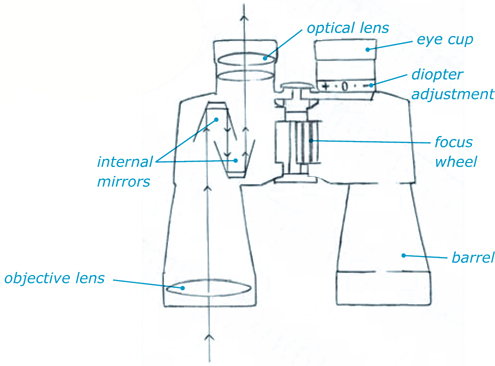

Before you try to see birds through your binoculars, you need to make a few adjustments. Virtually all binoculars have several helpful features that allow them to be tailored to different users. The eyecups hold the ocular lenses (the lenses you look through) exactly the right distance from your eyes (this distance is called eye relief), to optimize magnification and cut out peripheral light, making the image clearer and brighter. Extend the eyecups if you don’t wear eyeglasses. Since eyeglasses hold binoculars away from the eyes and let in peripheral light anyway, retract the eyecups if you do wear glasses.

Next, set the barrels of the binoculars to match the distance between your eyes. Looking through them, adjust the barrels until you have a solid image through both eyes. If the width isn’t set properly, your image will black out.

Virtually all binoculars on the market have center focusing, in which a single knob or lever controls the focus for both eyepieces simultaneously. Our eyes are seldom precisely matched, so to accommodate the difference between our two eyes, binoculars also have a diopter adjustment near the optical lens on one side or the other, or as part of the center focus knob. Diopter adjustments are normally numbered from +2 to –2.

Here’s how to adjust your binoculars so you can use them without eyestrain:

First find the diopter adjustment and set it at zero.

First find the diopter adjustment and set it at zero.

Find something a good distance away that has clean lines. A sign or something else with letters or numbers is often a good choice.

Find something a good distance away that has clean lines. A sign or something else with letters or numbers is often a good choice.

Cover the objective lens (the large outside lens of the binoculars) with the lens cap or your hand on the side controlled by the diopter adjustment, and then focus on the sign using the center focus knob. Try to keep both eyes open as you do this.

Cover the objective lens (the large outside lens of the binoculars) with the lens cap or your hand on the side controlled by the diopter adjustment, and then focus on the sign using the center focus knob. Try to keep both eyes open as you do this.

Switch hands, uncovering the lens with the diopter adjustment and covering the other lens. Focus again, this time using the diopter adjustment, not the center focus.

Switch hands, uncovering the lens with the diopter adjustment and covering the other lens. Focus again, this time using the diopter adjustment, not the center focus.

Repeat each adjustment a couple of times. After you’re done, your sign should be crisply focused through both eyes.

Repeat each adjustment a couple of times. After you’re done, your sign should be crisply focused through both eyes.

Notice the number setting on the diopter adjustment. Sometimes during normal use, the adjustment knob may get shifted, so every now and then, check to make sure it’s set where it should be for your eyes.

Notice the number setting on the diopter adjustment. Sometimes during normal use, the adjustment knob may get shifted, so every now and then, check to make sure it’s set where it should be for your eyes.

Finally, make the neck strap as short as it can be while still allowing you to use the binoculars comfortably and put them over your head easily. The longer the strap is, the more the binoculars will bounce, and the greater the chance you may bonk them against rocks, tables, and other objects whenever you bend down.

Finally, make the neck strap as short as it can be while still allowing you to use the binoculars comfortably and put them over your head easily. The longer the strap is, the more the binoculars will bounce, and the greater the chance you may bonk them against rocks, tables, and other objects whenever you bend down.

Q I think I have my binoculars perfectly set for my eyes, but I just can’t find any birds with them! There can be a cardinal sitting in a tree right in front of me, but when I pull up the binoculars and try to scan, the bird flies away before I can find it. What should I do?

A When you find a bird, keep your eyes on it while you place the binoculars in front of your eyes and focus without moving your head. Practice this with inanimate objects first. Starting with large items, test yourself to see how quickly you can spot something and pull up your glasses to view it. It can be frustrating at first, but once you master finding inanimate objects and resting birds, finding moving birds through your binoculars will soon become second nature.

The largest Red-tailed Hawks weigh three pounds. A dog about the size of a red-tail would weigh at least 10 times that!

BUY THE BEST BINOCULARS YOU CAN

BUY THE BEST BINOCULARS YOU CAN

There are hundreds of kinds of binoculars, and almost as many opinions about how to choose them as there are birders. The trick is to find the ones that are best for you and your budget, keeping in mind six key features of binoculars: prism type, magnification, brightness, field-of-view, comfort, and price.

Types of Binoculars

There are two basic binocular types: roof prisms and porroprisms. There is one more mirror inside roof prisms, which means the view is slightly dimmer, which is a serious consideration when you’re buying on a budget. For the same price and manufacturer, porroprisms give a slightly better image. That said, the design of porroprisms makes it easier for dirt and grit to get inside the binoculars, and they’re harder to waterproof. Most top-of-the line binoculars are roof prisms because they are so much easier to keep clean. Avoid choosing binoculars that have separate focus adjustments for each barrel — these are a very poor choice for birding, when you need to locate the bird and focus quickly.

Magnification and Brightness

Every pair of binoculars is described with two numbers, such as 8×40, 10×50, or 6×32. The first number is the magnification and the second number tells you, in millimeters, the diameter of the objective lens, which affects the brightness of the image. The magnification number tells you how much closer objects appear through the binoculars. Ten-power glasses bring things ten times closer. For otherwise identical binoculars, the higher the power, the closer the bird appears. There is a trade-off: the image will appear dimmer and the field-of-view will be smaller than through the same binoculars with lower magnification.

I use 6x binoculars, and if I’m looking at the same kettle of hawks as a birder next to me with 10× binoculars, I will be able to see more birds in my field of view at any given moment. If someone yells out that there’s a Golden Eagle flying in, I’ll usually be able to find it more quickly because of that wider field of view. The trade-off is that the other birder will be able to see more detail on the birds because of the greater magnification.

If there’s a strong northwest wind and we’re both shivering, the view through my 6x binoculars will be less shaky. If we’re looking at shorebirds on a hot, sunny afternoon, my 6× glasses will show less distortion. For a given price point from the same manufacturer, the optics of lower-power glasses virtually always provide a crisper, clearer view than those of higher-power glasses, especially noticeable with lower-quality binoculars. And yet, those higher-power glasses do bring the birds closer.

For binoculars of the same magnification, the bigger the second number is, the brighter your image — a good thing. But the bigger that number is, the heavier the binoculars are — a bad thing. You’ll optimize the amount of light gathering if the second number is at least 5 times the first number; that is, 6×30, 7×35, 8×40, or 10×50. This guideline is particularly important when you’re buying inexpensive or even mid-range binoculars, which don’t have the superior coatings and special low-dispersion glass that top-of-the-line binoculars have.

This should be another important consideration. Don’t choose binoculars that are so heavy you won’t want to use them. Make sure that when you look through them, you see one full image. If the eyepieces are too far apart, or if the binoculars aren’t well suited to the kind of glasses you wear, you may see two images or a partial image. It should also be easy for you to reach and turn the focus wheel.

Try binoculars within the highest price range you can comfortably afford, and rank them based on your preferences for magnification, brightness, sharpness, field of view, and comfort. Try to look at the same object in the distance with each pair so that you get a useful comparison. Once you settle on a pair of binoculars, stop reading about new models and comparing your glasses with those of other people! There really is no perfect binocular, and you’ll maximize your satisfaction by putting your focus back on birds.

Q I share my binoculars with my wife, and our eyes are different. Do we need to shift the diopter adjustment every single time we pass the binoculars between us?

A Although you’d both get your clearest view by readjusting the diopter every time, that’s sure not a fun way to go birding! You might try setting the adjustment halfway between her number and yours. If this bothers one of you more than the other, shift it a little toward that person’s proper setting. Some married birders regret not checking out their partner’s diopter adjustment number before making a lifetime commitment. Others just go ahead and buy a second pair of binoculars.

Q Two experienced birders in my town got into an argument on a field trip, debating how often they should clean binoculars. One said he cleans them before every birding outing. The other said you should never clean binoculars unless they’re noticeably dirty. What do you think?

A Most of the value of expensive binoculars is due to the quality of the lenses and coatings. Sand, dust, and other particles on the lenses can easily scratch coatings and even the glass, so it’s important to keep your binoculars dust free. When not in use, and that includes when you’re snacking or eating lunch with the binoculars around your neck, keep the optical lenses covered with the lens caps or rain guard.

I try always to keep a photographer’s lens brush in my birding jacket so when I notice dust on my lenses I can blow and brush it off quickly without the risk of grinding it into the lens with a tissue or cloth. I clean my binoculars at most once or twice a month when I’m birding intensively. When I clean them, I always first use the lens brush to gently sweep and blow particles away. If the eyecups are removable, you can unscrew them to brush everything completely off the lens.

After removing all dust, I moisten the corner of a high-quality lens cloth with a lens cleaning solution made specifically for coated binocular lenses (never use window cleaner!) and softly wipe the lenses clean. Then I buff the lenses with the dry portion of the cloth.

WHAT TO DO WITH OLD BINOCULARS

Many birders keep their old optics on a closet shelf just in case anything happens to their new ones. As insurance, this isn’t a bad idea, but if your old optics are in usable condition, you may want to put them to work so that others can enjoy birds and protect their future. How? Donate your old optics to a local nature center or birding club, or to an organization such as the American Birding Association’s Birder’s Exchange, or to Optics for the Tropics.

Many birders keep their old optics on a closet shelf just in case anything happens to their new ones. As insurance, this isn’t a bad idea, but if your old optics are in usable condition, you may want to put them to work so that others can enjoy birds and protect their future. How? Donate your old optics to a local nature center or birding club, or to an organization such as the American Birding Association’s Birder’s Exchange, or to Optics for the Tropics.

Both organizations send used (and sometimes new!) binoculars to researchers and educators in Latin America and the Caribbean. Information about Birder’s Exchange is on the ABA website at www.americanbirding.org/bex, and about Optics for the Tropics at www.opticsforthetropics.org.

Q What makes a spotting scope different from a telescope? And do I really need one?

A spotting scope is a portable telescope that has been designed specifically for observing objects here on earth. The magnification of a spotting scope is typically on the order of 20× to 60×.

No one needs a spotting scope. But a spotting scope will make views of waterbirds, shorebirds, and grassland birds ever so much easier. It can even give you amazing close-up views of woodland birds, especially on or near their nests when you don’t have to follow a moving object.

Q How do I choose a spotting scope?

A There are two basic scope designs: straight and angled. I used a straight scope for the first 30 years I birded. A straight scope makes it easy to home in on your bird unless it is well below you (as when you’re birding on a ridge or bluff) or quite high up. Straight scopes are not easy to share with large groups, or even with family members, unless everyone is close to the same height. Tall people have to scrunch down to see through a scope set up for a short person.

I bought an angled scope in 2005. There was definitely a learning curve in figuring out how to get the bird into the view because you have to look down into the eyepiece to see a bird that is straight ahead. But now that I’m used to it, I’d never consider going back. Angled scopes, like porroprism binoculars, have one fewer glass element, and that gives them a slight edge over straight scopes optically. Also, when a bird is very high or very low, it’s easy to rotate most angled scope models in their housing so you can more comfortably look through the eyepiece sideways. And when the scope is set up for the shortest person, the tallest ones don’t have to scrunch down — they can simply bend over a bit to look down through the eyepiece.

Most birders use zoom eyepieces on spotting scopes. These are usually configured to magnify 20× to 60×. I usually prefer using a fixed 30× eyepiece, but the zooms are quite satisfactory for most people and have a broader value in a lot of birding situations.

The objective lens of most spotting scopes ranges in size from about 60 mm to about 85 mm. As is true of binoculars, spotting scopes with larger objective lenses gather more light than scopes with smaller ones. The less expensive the scope, the more important it is to get a larger lens to ensure your image is bright and crisp. If you can’t afford the best, the rule is just like the rule for inexpensive binoculars — the bigger the objective lens and the lower the power, the clearer and brighter your view will be.

Q How do field trip leaders get so fast at finding distant birds in their scopes?

A The more you scope birds, the faster you’ll be. If you use a zoom eyepiece, always start out at the lowest magnification while you scan; once you’ve found the bird you can zoom in.

As with learning to use binoculars, practice on distant trees and other objects first. When I bought my first spotting scope, I started a list of all the birds I saw through it. It was slow going the first couple of weeks, but with the motivation of a growing list, soon I could find things in it amazingly fast!

Q When I go to my local birding club’s website, I see zillions of photos taken by birders. I thought photographers needed all kinds of special equipment and to hide in blinds, but some of these pictures were taken by people on field trips. How can people take decent photos while keeping up with a field trip group?

A Many camera companies sell “extended zoom” cameras that can zoom in 15× or even more, with image stabilization so the photos are reasonably sharp. I take one of these cameras everywhere.

Another strategy for taking photos while birding is to hold a small digital camera close to a spotting scope. To hold the camera steady and at the optimal distance from the optical lens, some optics companies sell special adaptors, and some birders create makeshift adaptors from such things as cold-medicine measuring cups or the upper part of plastic vitamin bottles. I’ve taken some very high-quality photos this way. Taking digital pictures through a spotting scope in this way is called digiscoping. You can learn about techniques and see examples at www.allaboutbirds.org.

Q I see lots of birders using electronic gadgets. What are they doing?

A Birders trying to keep up with rare bird sightings in their area can get updates by means of Internet Listservs, catching up on the latest posts on their iPhones, or through other devices. Some birding networks send out cell phone text messages when a rare bird is sighted. A lot of birders nowadays carry iPods, iPhones, or mp3 players with earbuds or a small speaker. Sometimes they review bird songs while trying to identify birds, and sometimes they play recordings in the field to try to lure birds in for a closer look; this is called playback. I’ve done this a few times, and it can be amazingly effective, but it can also be disruptive for birds exhausted from migrating or busy with nesting responsibilities. Playback should never be done to call up hotline rarities that dozens or hundreds of other birders are trying to find — this kind of constant disruption is suspected of causing nest failures, making birds fly off to quieter places, and even leading to a bird’s death. It also should never be done in popular birding locations where there are plenty of disruptions anyway.

Other electronic gadgets that birders might carry in the field include recording equipment — parabolic or shotgun microphones and recorders. Now that it’s possible to get reasonably priced digital recorders not much bigger than a deck of playing cards, more and more birders may start making their own high-quality sound recordings. Of course, many birders also carry cameras that take photographs and/or video.

Q Is there any equipment a birder should have besides binoculars, a field guide, and maybe a spotting scope?

A Yes. Every birder should always carry a field notebook and pen or pencil. A field notebook is indispensible for keeping track of what you see — not just for listing each species but also noting how many you see and any interesting behaviors you observe, the places you go, and weather conditions. When you’re starting out, you may want to record what field marks you note on each bird, especially unfamiliar species. It takes a bit of discipline to get into the habit of writing things down every 15 minutes or so when on an outing, and sometimes when you go out wanting to feel as free as a bird, a notebook may make you feel encumbered. But you’ll soon be grateful for the memories and will have good habits when you encounter a rarity that requires documentation.

Birding stores sell waterproof spiral notebooks, but less expensive small notebooks can work well under most field conditions. To minimize weight, some people keep a small ring binder at home and tuck just a few sheets, folded if necessary, into their field guide. A daily checklist sheet can be useful if it leaves plenty of room for keeping track of numbers for each species and for notes. Your notes will be fun for you to review in coming years. You can multiply their value many times over if you also enter the data at www.ebird.org.

Q There are so many field guides to choose from! How do I pick one?

A Begin by browsing the field guides at the library or bookstore to get a sense of which one works the best for you. Most experienced birders prefer a field guide with drawings by an expert rather than one with photographs. Good bird artists portray birds in similar poses, using their experience and knowledge to make it easier for you to key in on the important field marks. With photographs, lighting conditions and differences in bird postures can obscure important features or highlight unimportant ones, although the photos in some well-done guides are digitally manipulated to make color comparisons among different species more accurate.

Size is very important with a field guide, because if your book is too large, you won’t want to carry it in the field, but if it’s too small, it may not include all the birds you’re likely to see in your area. If you hope to eventually become proficient at birding, it’s wise to start with a guide that shows all the birds of North America or at least all the birds of the East or the West.

Hawaii’s Birds, a small guide published by Hawaii Audubon, is the only field guide with complete coverage for a single state. Other than that one, I never recommend using guides that show the birds of a single small area — almost every beginner sees at least a few species in the first several months of birding that aren’t included in more minimalist guides, leading to mis-identifications and frustration.

Keep these things in mind as you browse through several field guides, and pick a few that seem best on an overview. Now look up two or three birds that you’re very familiar with in each one. In your judgment, which seem closest to how you’ve experienced those birds? Consider color and poses. Also, how easy is it to find each of these familiar birds in the book? Remember: With field guides as with optics, there is no “best.” Beyond a few basic issues, it’s a matter of personal preference.

Q I can find birds I know in a field guide by using the index. But if I don’t know what the name is to use the index, I can never seem to find the bird in the book before it flies off. What am I doing wrong?

A The birds in most field guides are not organized alphabetically or by color, but according to how they are related to one another. Probably the single most important thing to do when you buy a field guide is to read it cover to cover, familiarizing yourself with each group of birds. Pick your book up several times a day and thumb through it, paying attention to the shapes and relative sizes of the birds, color patterns, and notes about behaviors and habitat.

You may notice that many swimming birds that seem to be shaped like ducks aren’t grouped with the ducks, geese, and swans. Grebes, loons, coots, pelicans, cormorants, and even tiny shorebirds called phalaropes all swim in a ducklike manner. But despite the superficial similarities that all these birds share, they represent several different genetic lines so are found in different sections of most field guides.

Although color patterns are important, being able to place birds in families is even more critical. Many birds have all-white plumage except for black wingtips, including American White Pelicans, Snow Geese, Whooping Cranes, White Ibises, and gulls; if you see one of these, its color pattern won’t be very useful until you get to the pages that show its family. And in poor light, you may not get a good sense of color at all. So shape and posture are usually the first features to pay attention to.

As you flip through your field guide and come across an interesting species, don’t read just the species account — go back and read that bird’s family profile as well, and notice how it compares and contrasts with its close relatives. By doing this frequently, your guide will soon become a familiar friend, and you’ll be able to recognize bird families, which is an important step toward mastering bird identification. The more you do this at home, the quicker you’ll be at identifying birds in the field.

Q Why don’t they organize field guides by color? That would make things so much easier!

A If field guides were organized by color, it would certainly make it easy to find birds that are only one color, such as swans or cardinals or crows! But where would the authors place a bluebird? Many times, of course, we see the brilliant blue back, but from the front, a perched Eastern or Western bluebird appears far more red than blue. Is a Great Black-backed Gull black or white? Would a Red-winged Blackbird go in the black section or in the red section? Is a Painted Bunting red, blue, or green? If we were to choose all the conspicuous colors for each bird and show them in each of the relevant color sections, the book would be too heavy to call a field guide!

Q While cleaning my grandfather’s attic, I found several of his notebooks, filled with bird lists and details about where and when he saw the birds. Some of the records went back to the 1940s! Would this information be useful to anybody?

A Absolutely. Ornithologists are keenly interested in long-term data about birds, especially if it includes information about the number of birds seen. However, the data can be useful only if they’re in a format that researchers can access and then analyze the information. I hope you’ll consider entering your grandfather’s data into eBird at www.ebird.org. A project of the Cornell Lab of Ornithology and the National Audubon Society, eBird enables birders to contribute their sightings to a permanent database online. The information then becomes accessible to scientists and birders alike through maps, graphs, and tables.

Birders who have kept electronic records in other formats can upload their sightings to eBird as well. Anyone can enter sightings of birds at any time, whether from this morning’s bird-watching trip or from a list from decades ago.

Q I have so many problems spotting birds in the woods. I can hear plenty of them in the trees but usually can’t see even one! What am I doing wrong?

A The thick branches and foliage of trees and shrubs makes forest birding a challenge. You’ll need to be patient to be successful. Get into the habit of looking along every branch, and if you’re hearing any voices, looking patiently through the branches for the singer. Sometimes it’s hard to gauge direction and distance from a bird by sound unless we walk around a bit — making a couple of steps to your right and left may help you figure out more precisely where the bird is.

Some birds flit about as they sing, so the sound will be moving with the bird. Some birds hold still for many minutes while singing. If you can’t pick out their shape, you’re not going to see these until they fly off. If these birds are at treetop level, they can be especially tricky to find because so many leaves and branches obscure them. Looking around for better vantage points — a big boulder or tree stump to stand on, a little opening giving you a wider view — will help.

During migration, warblers, vireos, kinglets, and other migrants often seek out chickadees to associate with. Chickadees know every little thing about their woods, and don’t mind company, so migrants associating with them can more effectively find food and elude predators. It’s a good idea to listen for chickadees and paying special attention to any little birds moving about when chickadees are around.

Lower-power binoculars are especially useful in forests. They give a wider field of view than higher-power ones, so there’s at least a little higher probability that “your” bird will be in view; and for the same size, they provide a brighter image than higher-power glasses, which is especially useful in shady areas with a dense canopy.

Birders in forests often try “pishing,” which means making spish spish spish sounds that may sound like a baby bird in distress. Pishing sometimes brings birds in for a momentary view. You still have to be alert, because when birds come in to check you out, they may still be concealed in foliage.

Unfairly, at least from the standpoint of a novice, the more birds you have seen in forests, or any other habitat, the more birds you will be able to see. The first ones can be ever so tricky, but as you get to know each one, you’ll recognize the kinds of vegetation and where within it each species is most often found. With every new bird you find, finding the next one will be that much easier.

Don’t get discouraged when you go out with an experienced birder who calls out all kinds of birds you don’t see. Most experienced birders recognize bird voices, and most of the birds they call out were heard but not seen. And don’t be afraid to ask them for advice and to point the birds out. Almost all will be happy to share their expertise.

Q Is it better to go birding on my own or with a group?

A Attending local birding field trips or going birding with more experienced birders can provide a lot of shortcuts for beginners trying to become proficient. You’ll learn the best hot spots, glean all kinds of valuable tips from experts, test out spotting scopes, and build up your life list much more quickly than you could on your own. And the fun of birding can be enhanced by the camaraderie of like-minded enthusiasts.

That said, in my opinion you should spend at least as much time birding alone as you do on organized field trips. On field trips, novice birders have a tendency to defer to experts and those with more experience, and even to shut off their own sense of inquiry when the answers are so readily available. The more time you spend teasing out frustrating identifications on your own, the more skilled you’ll become. Another advantage of going solo is that you can explore places that aren’t as popular, and occasionally discover “good birds” that no one else would have found.

A birding buddy can enhance your birding experiences wonderfully. The trick is finding the right one. The ideal birding companion shares your birding rhythms and your financial and time constraints, shares your level of competitiveness, is roughly your equal in skills so you can learn from one another and egg each other on to higher skill levels, and is fun to be with on long trips. Ideal birding buddies are hard to find! But if you can find a group of like-minded birders who enjoy being together from time to time, you can enjoy convivial company and save money and gas when headed to fairly distant birding sites or chasing hotline birds.

Q Some people say we shouldn’t worry about what colors we wear when birding. Others say not to wear bright colors, and some say we shouldn’t wear white but anything else is okay. I noticed when people were searching for the Ivory-billed Woodpecker, they were all wearing camouflage. Who should I believe?

A I’ve seen plenty of birds when wearing bright colors, including hummingbirds that were attracted by my bright red hat, an oriole that was drawn in by my bright orange University of Illinois sweatshirt, and a Red-winged Blackbird that waged a brief but fierce territorial battle with my red-striped bicycle helmet. That affirms that birds do, indeed, notice bright colors. But keep in mind that for every bird attracted to a bright color, another bird might have been alarmed after spotting you and stayed out of sight.

Many birders consider white the single worst color to wear because pure white is so conspicuous. Many animals, from white-tailed deer and cottontail rabbits to Dark-eyed Juncos, take advantage of the conspicuousness of white to flash it when running away, which may serve as a warning to others in its group to also flee. Remember, it’s not the color that birds are afraid of — it’s you. So it’s probably prudent to wear inconspicuous field clothing when possible.

Of course, even if we’re wearing camouflage, it’s hard to believe that birds, with their superior senses of vision and hearing, aren’t aware of our presence; although most bird photographers affirm that they get the most reliable opportunities for photos when they blend into the background as much as possible. Many field trip leaders ask that participants dress in dull colors. Whether or not you agree with their reasoning, it’s a courtesy to comply.

Much more important than clothing choices are walking fairly slowly, not making sudden quick movements, keeping your voice down, and stopping often to quietly look and listen.

Q I saw a rare bird but no one in the local birding club believes me. How come birders are so arrogant?

A Don’t feel bad — birders question even the most experienced birders among us! It isn’t a matter of arrogance; it’s a matter of ensuring that every single bird recorded by a state or local birding organization has been identified with as close to 100 percent certainty as humanly possible. To get a rare bird included in the body of records for most birding or ornithological organizations, you need to clearly show that you’ve seen all the critical field marks and excluded every possible similar bird. Because it’s becoming so easy to take photographs in the field, more and more organizations are now requiring photographic evidence to accept exceptionally rare or new species on their lists.

A life list is the list of all the wild bird species seen during a birder’s life. Most birders count only birds they see in nature, not zoo or pet birds, or birds at wildlife rehabilitation facilities. The competitive sport of birding involves seeking out and identifying birds in the natural world. Birds that are captive don’t meet that requirement.

Of course, your bird lists are your own personal business, and if you want to count birds you’ve seen in zoos and aviaries, or even birds you’ve seen on TV, you can do so. But when someone asks, “What’s your life list at?” or “How many birds have you seen?” your answer won’t necessarily make sense to anyone but yourself if you aren’t following the rules of the American Birding Association (ABA).

The ABA keeps track of birding lists for people who want to bird competitively. At the top of their 2007 list is Tom Gullick of Spain, who has seen 8,702 birds in the world. Macklin Smith of Michigan tops the North American (north of the Mexican border) list with 876 species, and also tops the list of birds seen in the United States including Hawaii with 921 species. (Canada has very few birds not found in the continental United States and Alaska, but Hawaii adds a great many to the list — not only native species but also the many birds that have been introduced and become established there, as well the pelagic birds seen along the coast.)

The ABA’s annual lists of records, including top lists for every U.S. state and Canadian province and every continent and country, can be found on the Internet, indexed at www.aba.org/bigday. To make a level playing field, birders have to follow the same rules of listing, which are available on the website.

Q What should I do when I see a rare bird?

A While you’re in the field, write down every single field mark, posture, and behavior you observe, as well as size comparisons with objects or other birds near the rarity. It’s best if you can draw or, better yet, photograph the bird. Write down your thought process: how did you come to think it was X rather than Y or Z, and be sure to explain how you excluded every similar species. If your state has a rare bird report form, keep a copy of it tucked in your field guide for just this occasion and fill it out as you watch the bird.

Don’t shy away from using your field guide after getting a thorough look at the bird, but be sure to read the text to make sure you’re noticing all the important field marks and comparing your bird with every similar species. Advanced birders say you’ll lose credibility if you say that your bird “looked exactly like the picture in the book.” If you do compare your bird to a field guide illustration, be sure to point out the specific ways that your bird did look like the picture, but also how it differed.

After the bird leaves, check your references to ensure that you haven’t missed anything you should have seen. When you are certain about your identification, let your local birding hotline know about it unless the bird may be vulnerable to spooking under pressure by a lot of birders gawking at it. Also, report the bird to www.ebird.org and your local and state birding organizations. Depending on how rare the sighting is, you may need all those notes you took!

Q I’ve read about places in the United States where more than a hundred thousand hawks fly past in a single day, and about a place in Mexico where more than a million birds may fly past in a single day. How is it possible to count so many?

A I can give you an example of a count I witnessed on September 15, 2003, at Hawk Ridge Bird Observatory in Duluth, Minnesota, when a total of 102,329 hawks were counted. Fully 101,698 of them were Broad-winged Hawks. There were also 445 Sharp-shinned Hawks and 83 American Kestrels. No more than 35 individuals were counted of any other species. How did they count them all and keep the species straight?

That day there were several counters, each in charge of one area of the sky, and each counter had a volunteer assistant recording birds. Hawk Ridge is a bluff a mile from Lake Superior. One counter was in charge of counting birds flying above the lake, with sky and water in the background. Another counted birds below the ridge, with houses and trees in the background. One took the birds flying overhead, and one took the birds along the far side of the ridge, opposite the lake. The birds weren’t crossing paths because they were all moving parallel to the lake, but other experienced birders at the count station were keeping track of the overall movement patterns to alert the counters if there were any shifting paths so birds wouldn’t be counted twice.

The counters counted Broad-winged Hawks, sometimes by tens and sometimes even by hundreds, and then called out the final number for each kettle (a swirling mass of hawks numbering anywhere from about five to many thousands) to the assistant who wrote down the number. Meanwhile, as Sharp-shinned Hawks passed by, the counters clicked them on a mechanical clicker. Every hour that number was recorded and the clicker reset to zero. As the counter was counting these two species, if a bird of another species went by, the counter called it out for the assistant to record individually.

That was, as of the end of the 2008 hawk-counting season, the biggest day ever at Hawk Ridge. The second largest flight was recorded on September 18, 1993, when 49,548 were counted. Hawk Ridge averages about 100,000 or so hawks through an entire season from August until November. The Hazel Bazemore Hawk Watch in Corpus Christi, Texas, pretty much directly south of there, often reports single day totals of more than 100,000 hawks — sometimes as many as 400,000 — and averages about 720,000 hawks a year. The record flight there happened on September 28, 2004, with a total day’s count of 520,267 raptors including 13 species. Of that day’s count, 519,948 were Broad-winged Hawks.

Q I want to plan a trip to see migrants along the Gulf Coast in Texas next spring. How can I schedule this so I’m there on the best days?

A April is an ideal month along the Texas coast. Migrant songbirds begin arriving in large numbers early in the month, but maximum numbers of warblers fly in usually around the third week of April. On days with “weather events,” often after southerly winds in Mexico sent birds flying across the Gulf of Mexico but rain on the Texas coast stops them, numbers can be huge, with as many as 30 species of warblers!

Nearly every Broad-winged and Swainson’s Hawk in the world passes through Veracruz, Mexico, in a 15-day period each fall. Single day counts can surpass a million! And an even larger migration passes over the Panama Canal, where all the hawks flying from North to South America must funnel through.

Unless you happen to have your own private jet and can take off at the drop of a hat when favorable weather is about to arrive, there’s a huge amount of luck involved in being at any migratory hot spot on the best days of the season. Part of your strategy should be to find alternative birding plans if one spot doesn’t pan out. Learning about nearby birding spots ahead of time can provide an excellent “Plan B.” The American Birding Association publishes birders’ guides to many hot spots, which make researching the possibilities for any birding adventure fun and easy. Remember that migrants crossing the Gulf from Mexico often don’t arrive on the upper Texas coast until afternoon. So even if few birds are around in the morning, it’s often worth checking “migrant traps” again in the afternoon.

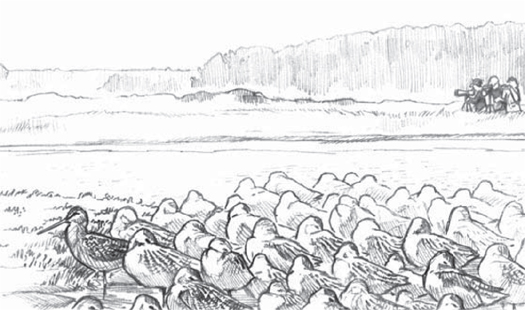

Counting large numbers of birds is yet another birding skill for which practice makes perfect. It’s easiest to start out counting smaller groups of birds that are perched or on the ground, and work your way up. Small flocks of a single species can be counted one by one. Larger flocks often must be counted in groups. Count by the smallest grouping you can.

Counting large numbers of birds is yet another birding skill for which practice makes perfect. It’s easiest to start out counting smaller groups of birds that are perched or on the ground, and work your way up. Small flocks of a single species can be counted one by one. Larger flocks often must be counted in groups. Count by the smallest grouping you can.

In most places you’ll usually be able to count single species flocks by fives or tens, but when you are at a major gathering place on a shore or wetland, you may have to learn to count by 20s or even 100s. If it’s a huge gathering, divide up the total flock into sections, count one section, and multiply by the number of sections to get a reasonable estimate.

To count flying birds, again practice on smaller groups. Block off a group of individuals, count them, and then extrapolate to the entire flock; or count birds per unit of time as they pass a specific point.

Q My daughter loves birds. What kinds of careers might be good for her?

A There are many branches of science she may want to explore, including ornithology, wildlife biology, ecology, conservation biology, behavior sciences, avian physiology, or veterinary medicine.

She might consider elementary education — in the proper hands, bird study can be integrated wonderfully into a multi-disciplinary program, and curriculum aids such as the Cornell Lab of Ornithology’s BirdSleuth program and Journey North’s online lessons can make teaching about birds much easier. High school biology teachers can introduce their students to birds and inspire them to learn about science.

If she has a legal mind, she may want to be an environmental lawyer with a background in bird conservation. A love of writing and of birds can be a great combination for a career as an environmental author, journalist, or radio host. If she wants to work outdoors, she may be able to do fieldwork for government agencies or nonprofits, or lead birding tours.

Blue Jays lower their crests when they are feeding peacefully with family and flock members or while tending to nestlings.

In some areas, the American Crow leads a double life. It maintains a territory year-round in which the entire extended family lives and forages together. But during much of the year, individual crows leave the home territory to join large flocks at dumps and agricultural fields, and to sleep in large roosts in winter. Family members go together to the flocks but do not stay together in the crowd. A crow may spend part of the day at home with its family in town and the rest with a flock feeding on waste grain out in the country.

In some areas, the American Crow leads a double life. It maintains a territory year-round in which the entire extended family lives and forages together. But during much of the year, individual crows leave the home territory to join large flocks at dumps and agricultural fields, and to sleep in large roosts in winter. Family members go together to the flocks but do not stay together in the crowd. A crow may spend part of the day at home with its family in town and the rest with a flock feeding on waste grain out in the country.

Communal crow roosts can range from a few hundred to two million crows! Some roosts have been forming in the same general area for well over 100 years. In the last few decades some of these roosts have moved into urban areas where the noise and mess cause conflicts with people.

Sometimes they conflict with people’s pets as well. I used to watch three crows that would arrive in my neighbor’s yard the moment she left for work every morning. As she headed out to the car, she would tie her Springer Spaniel up and give the fairly large dog a bowl of food. No sooner did she back her car out than the crows would drop down and walk slowly toward the dog, staring intently at her. The dog meekly backed away from her dish, and the crows stuffed their throat pouches with dog food before leaving for the day.

AMERICAN BIRDING ASSOCIATION’S PRINCIPLES OF BIRDING ETHICS

AMERICAN BIRDING ASSOCIATION’S PRINCIPLES OF BIRDING ETHICS

Birds often go about their business as usual even as you watch them, but birding, especially by large groups or in sensitive or popular areas, can cause stress for birds and can sometimes even damage their habitat. Birders should be especially sensitive around nests, since distressed birds may draw the attention of nearby predators.

The American Birding Association (www.aba.org) has created a set of guidelines to address situations in which birds may be harmed. Their Code of Birding Ethics emphasizes that “In any conflict of interest between birds and birders, the welfare of the birds and their environment comes first.”

Code of Birding Ethics

1. Promote the welfare of birds and their environment.

1(a). Support the protection of important bird habitat.

1(b). To avoid stressing birds or exposing them to danger, exercise restraint and caution during observation, photography, sound recording, or filming.

Limit the use of recordings and other methods of attracting birds, and never use such methods in heavily birded areas, or for attracting any species that is Threatened, Endangered, or of Special Concern, or is rare in your local area.

Keep well back from nests and nesting colonies, roosts, display areas, and important feeding sites. In such sensitive areas, if there is a need for extended observation, photography, filming, or recording, try to use a blind or hide, and take advantage of natural cover.

Use artificial light sparingly for filming or photography, especially for close-ups.

1(c). Before advertising the presence of a rare bird, evaluate the potential for disturbance to the bird, its surroundings, and other people in the area, and proceed only if access can be controlled, disturbance minimized, and permission has been obtained from private land-owners. The sites of rare nesting birds should be divulged only to the proper conservation authorities.

1(d). Stay on roads, trails, and paths where they exist; otherwise keep habitat disturbance to a minimum.

2. Respect the law, and the rights of others.

2(a). Do not enter private property without the owner’s explicit permission.

2(b). Follow all laws, rules, and regulations governing use of roads and public areas, both at home and abroad.

2(c). Practice common courtesy in contacts with other people. Your exemplary behavior will generate goodwill with birders and non-birders alike.

3. Ensure that feeders, nest structures, and other artificial bird environments are safe.

3(a). Keep dispensers, water, and food clean, and free of decay or disease. It is important to feed birds continually during harsh weather.

3(b). Maintain and clean nest structures regularly.

3(c). If you are attracting birds to an area, ensure the birds are not exposed to predation from cats and other domestic animals, or dangers posed by artificial hazards.

4. Group birding, whether organized or impromptu, requires special care.

Each individual in the group, in addition to the obligations spelled out in Items #1 and #2, has responsibilities as a Group Member.

4(a). Respect the interests, rights, and skills of fellow birders, as well as people participating in other legitimate outdoor activities. Freely share your knowledge and experience, except where code 1(c) applies. Be especially helpful to beginning birders.

4(b). If you witness unethical birding behavior, assess the situation, and intervene if you think it prudent. When interceding, inform the person(s) of the inappropriate action, and attempt, within reason, to have it stopped. If the behavior continues, document it, and notify appropriate individuals or organizations.

Group Leader Responsibilities [amateur and professional trips and tours]

4(c). Be an exemplary ethical role model for the group. Teach through word and example.

4(d). Keep groups to a size that limits impact on the environment, and does not interfere with others using the same area.

4(e). Ensure everyone in the group knows of and practices this code.

4(f). Learn and inform the group of any special circumstances applicable to the areas being visited (e.g., no tape recorders allowed).

4(g). Acknowledge that professional tour companies bear a special responsibility to place the welfare of birds and the benefits of public knowledge ahead of the company’s commercial interests. Ideally, leaders should keep track of tour sightings, document unusual occurrences, and submit records to appropriate organizations.

Please follow this code and distribute and teach it to others.