When we sit down to a Thanksgiving turkey dinner, our minds are usually filled with thoughts of family and our many blessings, but once in a while, we can’t help but wonder why turkeys have dark meat and white meat while geese have only dark. What’s the gizzard all about? And why don’t we ever see a turkey’s lungs?

Whether we’re questioning our food or trying to understand how vultures can breathe at high altitudes or how a gannet can plunge into water at 60 miles per hour, bird insides are fascinating, leading to all kinds of questions.

Q One time when I was on a cruise, the ship naturalist pointed out a gannet, flying up high and then dropping down like a bullet to dive into the water. How does it hit the water at such high speed without injuring itself?

A Gannets and their close relatives, the boobies, can plunge straight into the water from as high as 120 feet, hitting the surface at speeds that can exceed 60 miles per hour. To survive the impact, they dive so that their pointed bills enter the water first, followed by their streamlined bodies. Gannets have unusually strong skulls and rib cages, and their respiratory system includes tiny air sacs between their skin and their muscles that absorb the shock when they hit the water. Their external nostrils are closed, and their “secondary nostrils,” next to the bill, are covered by move-flaps that are closed when they hit the water. They can see schools of fish from the air, track them as they dive, and follow them underwater — a semitransparent inner eyelid, the “nictitating membrane,” protects their eyes.

Q When I was visiting my grandfather’s farm, he butchered a turkey for dinner and let me look at the organs. I could figure out where the heart, stomach, liver, and intestines were, but I couldn’t find the lungs at all! Where were they?

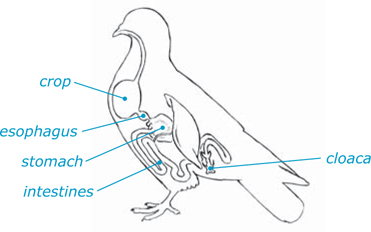

A Birds have high metabolic rates, and they exert intense energy while flying long distances, which requires proportionally more oxygen than mammals use. Mammalian lungs are huge, yet very light, and positioned right where a bird’s center of gravity must be for efficient flight. Birds have an extremely specialized respiratory system, unique in the animal kingdom, that allows them to extract much more oxygen from the air they breathe in than we can. To accomplish this, avian lungs are very small and flat, and rigid, not expandable. That turkey’s lungs were there, fitted perfectly against the bird’s back ribs, but so flat that they didn’t look at all the way you expected.

When birds breathe in, the tide of air that flows through the trachea is split. A small portion of it goes straight into the lungs for immediate exchange of oxygen and carbon dioxide. From there it flows into air sacs in the forward part of the body. Like bellows, when the bird exhales, these anterior air sacs push the oxygen-depleted air back into the trachea and out through the bird’s nostrils or mouth. A larger part of the inhaled air goes from the trachea straight back to posterior air sacs, and when the bird exhales, these sacs send the fresh air through the lungs and out through the trachea.

So all the air in the lungs at any given moment is fresh, unlike the air that remains and becomes mixed with carbon dioxide in the alveoli of mammalian lungs. The air sacs are huge in living birds, but most of the space they fill is behind the relatively heavier organs in the bird’s center of gravity.

When birds die, the weight of their organs and skin, along with air pressure from outside the bird, instantly flattens most of the air sacs, so you wouldn’t have been able to easily detect them in the turkey unless you put a straw down its trachea and blew — then the air would flow through the lungs to inflate the air sacs, which look like clear balloons.

Q When I saw the IMAX movie Everest, I noticed big black birds like crows up near the summit, where virtually all the people needed oxygen tanks. How can birds breathe at such high altitudes?

A The trick isn’t in breathing at high altitudes; it’s in actually getting oxygen from those breaths into the blood and getting carbon dioxide out when there is so little oxygen in the atmosphere. Bird lungs, a crisscrossing matrix of tiny air tubes and parallel capillaries, are exquisitely designed for this. Air passes through the tiny tubes in a direction countercurrent to the blood flowing through capillaries, making it extremely easy for the blood to pick up oxygen from the air tubes as the tubes pick up carbon dioxide from the blood to exhale. Every air tube in avian lungs is interconnected; bird lungs have no dead-air spaces such as the alveoli, where gas exchange takes place in mammalian lungs.

The whole point of the respiratory system is to get the right amount of oxygen to all the cells, which happens in conjunction with the circulatory system. Strong flyers tend to have smaller red blood cells than flightless birds and weak flyers. This difference is important because the smaller a cell is, the relatively larger its surface area for gas exchange.

As with human athletes training at high elevations to build up their red blood cells, birds that move to higher elevations or are subjected in laboratories to lower air pressure produce more red blood cells. Birds have slightly less hemoglobin in their red blood cells than do mammals, but avian hemoglobin is more efficient at picking up oxygen.

Those birds, by the way, are Alpine Choughs.

HEARTBEATS AND BREATHING RATES

Because birds inhale and exhale relatively large amounts of air in each breath, as compared with mammals, their breathing rates are much slower than those of mammals of comparable size. The smallest hummingbirds take about 250 breaths per minute while the smallest shrews take about 800. Of course, flying birds breathe more rapidly than resting ones: a duck at rest takes about 14 breaths per minute while a flying duck takes about 96.

Because birds inhale and exhale relatively large amounts of air in each breath, as compared with mammals, their breathing rates are much slower than those of mammals of comparable size. The smallest hummingbirds take about 250 breaths per minute while the smallest shrews take about 800. Of course, flying birds breathe more rapidly than resting ones: a duck at rest takes about 14 breaths per minute while a flying duck takes about 96.

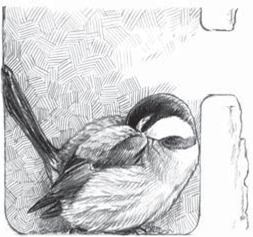

The rapid rate at which oxygen is taken up in the blood is reflected in a bird’s rapid heart rate. A mammal’s average heart rate is about 3 times its respiration rate whereas a bird’s average heart rate is over 7 times its respiration rate. A chickadee’s heart beats about 500 times per minute at rest and doubles that during activity. To pump blood efficiently, the heart of a bird is larger than that of a mammal of comparable size, and the heart is relatively larger in smaller birds than in larger ones. It’s also larger in alpine birds than in their relatives who live at lower elevations.

Q Why do chickens and turkeys have white breast meat while ducks and geese have all dark meat?

A Birds and mammals have two kinds of muscle fibers: white, or “fast twitch,” fibers and red, or “slow twitch,” fibers. Red fibers may not twitch as fast as white ones, but the red fiber cells are richly supplied with mitochondria and red muscle tissues are heavily oxygenated with a rich blood supply. This enables these fibers to work steadily for long periods, so birds capable of long bouts of walking or swimming, such as turkeys, chickens, ducks, and geese, have mostly red fibers in their leg muscles. Birds capable of sustained flight, such as ducks, geese, songbirds, hummingbirds, and the like, have mostly or even all red muscle fibers in their wing and breast muscles. Most birds have more red than white muscle fibers; some hummingbird and House Sparrow muscles are made of 100 percent red fibers.

White meat comprises mostly fast twitch white fibers but usually has at least a few red fibers, too. Gallinaceous birds in general (including turkeys and grouse) have white meat in their pectoral muscles, which means the muscle fibers are mostly the fast twitch variety allowing the birds to take off in flight with a powerful burst. These muscles are seldom capable of sustained flight, though wild gallinaceous birds such as turkeys and grouse can sometimes fly a mile or more before tiring.

The red fibers in “dark meat” are more useful for more purposes because they’re capable of sustained activity, but the trade-off is that they require more nutrients and a rich supply of blood vessels. Since gallinaceous birds don’t normally fly long distances anyway, they’re better off with the lighter, lower-maintenance white muscle fibers, giving them white meat. Ducks and geese, which need to engage in both sustained swimming and sustained flying, don’t have white meat at all.

Domesticated chickens and turkeys have been bred to have a higher percentage of white fibers in their white meat, as well as to have more meat in the first place. So Wild Turkeys may have darker colored meat than do domesticated turkeys, but it’s still considered white meat.

Q I’m pretty good at imitating bird calls, but there are some songs, such as the Wood Thrush’s, that I find impossible to whistle. I can’t come close to imitating the shimmery, complex quality of its song. How does it do that?

A Birds produce sounds with their syrinx (literally “song box”), which is situated at the very base of the trachea and the top of the two bronchial tubes. By controlling the muscles of the syrinx, some birds can make one set of sounds with the left branch and a different set of sounds with the right, producing harmony with their own voice. The most complicated sets of muscles in the syrinx belong to the thrushes, which is why so many of their songs sound so ethereal.

Q I was amazed to read that loons spend the winter on the ocean. How can they survive — are they able to drink saltwater?

A Yes, loons can drink saltwater when they are at sea because they have special glands that remove salt from their bloodstream. When they hatch, loons are freshwater birds, eating freshwater fish and drinking fresh water — until their first migration. The moment a loon gets a taste of saltwater, two glands near its eyes swell up and start removing excess salt from the bloodstream. The salt is excreted in the form of thick tears or mucous via the nasal passages. Our own bodies excrete excess salt by way of our kidneys and sweat glands, and our tears are as salty as our body tissues. The tears of loons in winter are much saltier than ours, or than the loons’ body tissues, because the excess salt is concentrated before excreting. When loons return to freshwater in spring, their salt glands shrink for the season. If a loon were to cry in summer, its tears would be no more salty than ours.

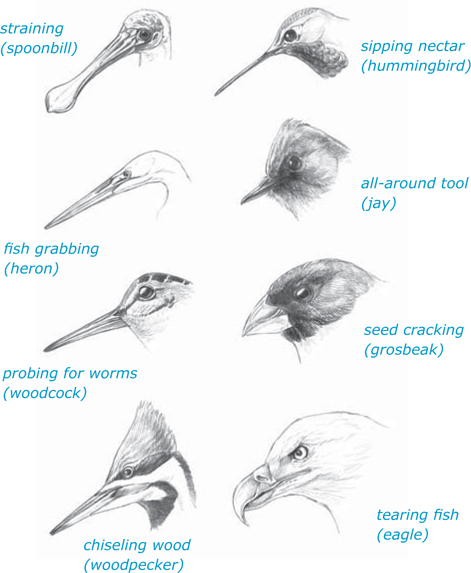

That’s what nineteenth-century ornithologist Elliot Coues called the avian skull. All birds have bills or beaks (synonyms for the same structure), but they display an amazing variety of adaptations to the environment.

That’s what nineteenth-century ornithologist Elliot Coues called the avian skull. All birds have bills or beaks (synonyms for the same structure), but they display an amazing variety of adaptations to the environment.

Some ocean birds, such as albatrosses, have huge salt glands that excrete the salt through exceptionally long nostrils, which give albatrosses, petrels, and shearwaters the name “tubenoses.” Excess salt can dribble out, as it does for loons, or it can be forcibly blown out through these specialized nostrils.

Some land birds, such as Budgerigars (our familiar pet “parakeets” or “budgies”), also have large salt glands. Wild Budgerigars, native to the interior deserts of Australia, drink from waterholes filled with brine water.

Q I once found a baby robin hopping on my lawn. There was a cat around so I picked the robin up and put it in a shrub where it would be safer. While I was carrying it, it opened its beak, begging for food. I was surprised that the inside of its mouth was bright yellow. Even weirder, the roof of the mouth had a most bizarre pattern, with something that looked like a serrated diamond pattern in the center. What was that?

A Many young birds, including robins, have mouths that are brightly colored on the inside. The color helps stimulate their parents to feed them when they open their mouths. On the roof of the mouth, you saw the opening to the bird’s nasal passages and its Eustachian tubes. When birds breathe through their nostrils, the air flows through the nasal passages to the glottis, a fairly large opening on the bottom of the bird’s mouth where the trachea begins.

Q Birds don’t have teeth, do they? How do they chew their food?

A You’re right, birds don’t have teeth. They use their bills to handle and prep food before they eat it, but they don’t actually need to chew their food before swallowing it. Hawks use their sharp bills to rip apart prey, then swallow chunks of meat. Finches and sparrows use their bills as a nutcracker to open hard-shelled nuts or seeds, which they then swallow whole. Birds that eat seeds can have many small mucous glands inside their mouth to help them lubricate the seeds before swallowing, and salivary glands that secrete enzymes to begin the digestive process.

We humans have a gag reflex that usually prevents us from swallowing large items until they’ve been pulverized by our teeth. But even fairly small birds can swallow chunks so big they’d make us choke. A tiny Saw-whet Owl has no trouble downing a whole deer mouse, and a Great Blue Heron can swallow huge fish whole. Birds that eat small food particles, such as insect eaters, may have a fairly narrow esophagus, but those that eat big chunks have an extensible esophagus that stretches to accommodate the food; the skin of their neck is equally stretchy.

Q I understand that “bird’s nest soup” is a delicacy in Chinese cuisine and that the nests are made of saliva. Is that true?

A Yes, the nests used in soup are constructed by Asian swiftlets whose gluey saliva hardens into a cup-shaped nest. The most heavily harvested nests are from the Edible-nest Swiftlet and the Black-nest Swiftlet, found mostly around the coasts of southern China and Southeast Asia, and inland where suitable caves exist. It takes about 35 days for each male to build a nest, constructing a shallow, gluey cup out of strands of saliva containing predigested seaweed, stuck to the wall of a cave. These nests contain high levels of calcium, iron, potassium, and magnesium.

Many sea birds swallow fish so large that several hours after swallowing one, while the fish head is slowly digesting in the bird’s stomach, the tail may still be sticking out the mouth.

Collecting them for soup is both difficult and dangerous. Nest collectors climb flexible rattan ladders dangling from the ceiling of the caves, then inch along bamboo ladders to gather nests adhering to the roof, as much as 200 feet above the hard cave floor.

Nests are collected twice a year. The first collection takes place after the swiftlets have built the nests but before laying eggs. The males rebuild, and at this point pairs are allowed to raise their young. After the nestlings fledge and families leave the cave, these second nests are collected. Swiftlets cannot be raised in captivity and their nests are fairly small, making the nests extremely valuable commercially. One pound of “white” nests (produced by the Edible-nest Swiftlet) can cost almost $1,000, and one pound of “red blood” nests (which may get their color from the insects the Edible-nest Swiftlet eats) can cost more than $4,000! Black-nest Swiftlet nests aren’t as valuable: they get their color because the bird mixes feathers with the saliva, and the feathers must be removed before using the nests for soup.

Three of the four North American swifts also use sticky saliva to hold their nests together and attach them to the walls of chimneys, hollow trees, and other structures, but their nests are hardly edible, being constructed of twigs, pine needles, weeds, and so forth. The Black Swift uses no saliva at all; its nest is just a shallow cup shaped out of mud or mosses on seacoast cliffs or behind mountain waterfalls.

Gray Jays have another unusual use for saliva: They coat chunks of food with copious amounts of saliva before fastening them to trees for storage. Researchers speculate that the saliva may help hold the food in place and possibly even retard spoilage somewhat.

Q Why do domestic birds such as chickens need grit with their food? Do wild birds also need grit to help them digest?

A Birds, like mammals, can’t absorb any nutrients until their food has been liquefied, which in the case of birds takes place almost entirely in the stomach. A bird’s stomach has two chambers. Food first reaches the proventriculus, a glandular chamber where powerful acids start dissolving the food. Then the food passes into the gizzard, a muscular chamber that mashes the food.

If you ever have the opportunity to get your hands on a chicken that has recently been feeding, hold its stomach up to your ear to hear the grinding sounds.

The gizzard is extremely powerful in birds that eat large or thick-walled seeds, such as turkeys, ducks, swans, chickens, sparrows, and finches. Seeds must be thoroughly pulverized to be digested. To accomplish this, most seed-eating birds pick up and swallow grit that remains in the gizzard for long periods as it is slowly dissolved and ground up by the digestive process.

Some kinds of grit have valuable minerals. For example, the slowly dissolving pieces of a pet bird’s cuttlefish bone release calcium into the bird’s bloodstream while it grinds up seeds in the bird’s gizzard. In the same way, many wild birds, from loons and swans to sparrows and finches, swallow grit to aid in digestion and obtain necessary minerals.

Q I’ve heard that a major problem facing many birds is lead poisoning. Why is that?

A Most of the pieces of grit that birds pick up are rich in calcium and other minerals, providing an important nutritional component as well as a digestive aid. Tragically, sometimes birds pick up bullets, tiny lead pellets from shotguns, or lead sinkers broken off from fishing lines. As these are gradually dissolved in the gizzard, the lead enters the bird’s bloodstream, making the bird weak and disoriented, and often killing it. Waterfowl were succumbing to lead poisoning in such significant numbers that lead shot has been banned for waterfowl hunting in the United States since 1991. But lead shot is still permitted in most areas for hunting upland game birds such as grouse and pheasants, and hunters are permitted to use lead bullets for deer and other large game.

Scavengers, such as vultures, condors, and eagles, that feed on pheasants and other upland game birds that have been shot but not retrieved are often poisoned by lead shot. Those that dine on large chunks of meat or gut piles from deer may ingest fragments of lead bullets that, like lead shot, remain in the gizzard, dissolving and slowly poisoning the birds.

The most common cause of mortality for California Condors that have been released back into the wild has been from lead poisoning. Chemical analyses of the lead in these birds matches the forms of lead used in the manufacture of bullets, so in 2007, California passed a law requiring deer hunters to use copper bullets in specified areas where condors forage.

Many scientists and conservationists believe lead bullets and shot should be banned for all hunting, arguing that other nonendangered species are also ingesting lead. Their case is gaining supporters among human health advocates as new research is finding significant lead amounts in venison eaten by hunters and donated to food shelves.

Q Why do owls regurgitate pellets?

A After an owl’s prey is dissolved in the glandular stomach, the gizzard squeezes the digestible material into the intestines while the bones, fur, teeth, and other indigestible matter remain. When all the liquid is finally squeezed out, what remains is spit out as a pellet. Hawks, crows, nighthawks, gulls, and some other birds also occasionally or even daily spit out undigested material as pellets, but owls produce the most solid ones.

The pellets collect beneath branches where owls roost during the day, providing both a useful clue for birders as to where an owl might be spotted and important information for researchers who are surveying small mammal populations. Such surveys help to determine how best to deal with agricultural pests that cause major economic problems for farmers.

Because owls usually swallow small prey whole or in two bites, the bones in an owl pellet tend to be fully intact and are usually easy to identify. Hawks, however, typically tear their meat apart, eating fewer bones in the first place, and hawk stomach secretions are significantly more acidic than those of owls, dissolving many of the bones they eat.

A bird’s skull must house its enormous eyes and a brain large enough to coordinate keen vision with precise muscle control. Because their food is pulverized in the gizzard, birds have neither teeth nor a bony jaw to support them.

Q How do bird intestines compare with those of humans? Are they longer or shorter relative to their size?

A Birds that eat nectar, soft insects, or meat usually have very short intestines, but birds that digest grasses and other foliage or grain tend to have significantly longer ones. The small intestine of an Ostrich, a bird that grazes on grasses and seeds, is 46 feet (14 meters) long, or double the length of a human small intestine!

Of course, flying birds can’t carry much weight, and so to reduce the weight they must lug around, most food is digested very quickly and efficiently. Rather than keeping food in the intestines for a long time, birds have a relatively huge liver (the heaviest internal organ) and pancreas, both situated in the optimal place for a flying creature’s center of gravity. Both of these organs secrete juices that speed up the digestive process. What remains in the intestines after all the nourishment has been absorbed enters the bird’s cloaca to be ejected when the bird poops.

The seeds of berries eaten by young Cedar Waxwings appear in their droppings just 16 minutes later, and seeds of elderberries eaten by thrushes pass through the digestive system in a mere 30 minutes. A Northern Shrike can digest a mouse in 3 hours, while the “bearded vulture” or Lammergeier of the Mediterranean (related to North American hawks) can completely digest a cow vertebra in a day or two.

A You may not care to examine bird droppings too closely, but if you do, you’ll see they’re usually made up of two different components. The brownish or dark greenish part is the fecal matter, or the poop. This is what remains after food has gone through the entire digestive system. The white part is actually urine.

Our urinary system filters our blood of impurities, which build up even before birth. Mammals eliminate these wastes as urea, a clear, yellowish fluid that is highly toxic and must be diluted with huge quantities of water. Birds and other animals that hatch from eggs eliminate the wastes from their kidneys as uric acid, a substance that doesn’t need to be diluted in huge quantities of water because when concentrated it precipitates into a chalky, whitish substance.

Q Do birds poop in flight?

A Birds tend to poop right before or during takeoff, and it takes a few minutes to build up another supply, so on short flights, no, they don’t. But on flights that last longer than a few minutes, yes, they can and do poop in the air. Normally if they’re fairly high up and going fairly fast, the poop atomizes long before it reaches the ground.

A few birds that drink huge quantities of water, such as hummingbirds, can produce urea as adults. Hummingbird droppings are usually droplets of clear liquid with tiny particles of fecal matter suspended within. Captive hummingbirds fed nothing but sugar water can’t survive for long, but while they do, they produce urine with little or no poop.

A few birds that drink huge quantities of water, such as hummingbirds, can produce urea as adults. Hummingbird droppings are usually droplets of clear liquid with tiny particles of fecal matter suspended within. Captive hummingbirds fed nothing but sugar water can’t survive for long, but while they do, they produce urine with little or no poop.

Seabirds, cormorants, gulls, and other birds that take in a lot of water with their fishy diets don’t produce urea, but they do release large amounts of uric acid compared to fecal matter. Those big white splats can be valuable; where these birds collect in large numbers, this guano can be collected for nitrogen- and phosphorus-rich fertilizers. Geese eating huge amounts of grasses produce smaller quantities of urine than fecal matter (which is mostly the indigestible cell walls of those grasses, hence its color and consistency).

The Green Heron, Black-crowned Night-Heron, and American Bittern have long been nicknamed “shite-pokes.” Apparently when the term was first used in the 1770s, the word “shite” meant the exact same thing as a more common term used today, but it was a perfectly respectable way of referring to these birds’ habit of shooting out a noticeable stream of poop on takeoff.

Q Every time I’ve ever seen an owl, in real life or in a photo, it had only two front toes. But last week I found a dead owl on the road, and it had three front toes. Was it a mutant?

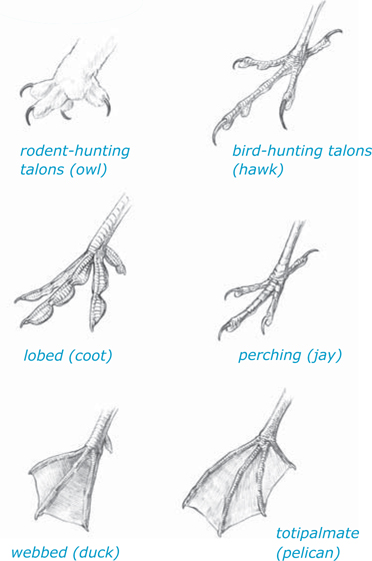

A No. All owls have three toes that face forward and one that faces backward. You only see two toes in front in perched owls because one of the forward toes is opposable, like our thumb, and rotates to the rear when the owl sits on a branch.

Another bird of prey shares this feature — the Osprey. Osprey feet are specialized for catching fish, with characteristic papilla called spicules covering the bottom of their feet. When they grasp a fish, the two always-facing-forward front toes are balanced by the rear toe and the opposable toe, making it harder for a thrashing fish to escape.

Bald Eagle feet lack some of the specializations of Osprey feet. When an eagle catches a fish, its three forward toes from each foot grasp one side of the fish while the single back toe from each foot grasps the other side. Eagle talons are powerfully strong with long, sharp claws, but if a fish thrashes hard enough, it may pull out of the eagle’s outer toes, forcing the eagle to shift its grip. Sometimes at this point the eagle may drop the fish. Eagles feed also on carrion and have a habit of stealing fish from Osprey, so despite being a bit less specialized, they have a wider margin of error.

I often have the fun of speaking to classrooms about birds. Once after I explained about eagles sometimes dropping their fish, a fifth-grade boy raised his hand and told me about a wall-eye he had caught that summer. “The fish had six scars on one side of its body, and two scars on the other, and I told my mom they looked like they came from eagle claws. But she said I had a big imagination.” He was elated when I told him he’d make a great forensic detective.

On March 30, 1987, an Alaskan Airlines jet was forced to make an unscheduled stop after the plane had a midair collision with a fish. During takeoff, right after it was too late to stop, the pilot suddenly saw several eagles flying above the plane. He gave a sigh of relief as he realized his flight path was safely beneath the massive birds, but one eagle apparently was startled and dropped its fish, which slammed into a small window at the top of the cockpit. The passengers, crew, and eagle all survived without injury, and damage to the plane was minimal. The only fatality was the fish.

Q Great Blue Herons look a lot like Sandhill Cranes, but someone told me they’re not related, and that it had to do with their feet. True or false?

A Herons and cranes do look a lot alike, superficially; but they have evolved in entirely different lines, and their feet show some important differences. Herons nest and roost in trees, and so they have a long, strong back toe that allows them to cling to branches. Cranes nest on the ground and never perch in trees. Their back toe is tiny and raised — completely worthless for perching. If you see a footprint with long, unwebbed toes, that was made in sand or mud, you can tell if a heron or a crane made it by looking for signs of a back toe.

Most wild birds never see their first birthday. There are so many dangers out there that birds produce fairly large numbers of young simply to ensure that during their lifetime there will be offspring to replace them.

But once an individual bird has survived its first year and has developed skills to negotiate each season, its life expectancy goes up dramatically. We can tell how long some individual birds have lived in the wild if they were banded with a U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service leg band and were recaptured or found dead at a later time. The ten longest-lived species recorded by the U.S. Geological Survey’s Bird Banding Laboratory in Laurel, Maryland, as of February 2008 are:

|

50 years 8 months |

|

40 years 8 months |

|

38 years 2 months |

|

35 years 11 months |

|

35 years 10 months |

|

34 years 7 months |

|

34 years |

|

32 years 8 months |

|

32 years 5 months |

|

31 years |

Every one of those “top ten” birds is a species that spends its life on the ocean. But some inland species have surprisingly long lives, too. Here are some randomly selected records, from shortest to longest known lifespan:

|

3 years |

|

5 years |

|

8 years |

|

8 years |

|

9 years |

|

9 years |

|

10 years |

|

10 years |

|

10 years |

|

11 years |

|

11 years |

|

11 years |

|

12 years |

|

12 years |

|

13 years |

|

13 years |

|

13 years |

|

14 years |

|

14 years |

|

14 years |

|

15 years |

15 years |

|

|

16 years |

|

16 years |

|

16 years |

|

17 years |

|

17 years |

|

20 years |

|

24 years |

|

26 years |

|

27 years |

|

27 years |

|

30 years |

|

30 years |

|

31 years |

|

31 years |

|

31 years |

An American Robin can produce three successful broods in one year. On average though, only 40 percent of nests successfully produce young. Of those that fledge, only 25 percent survive to November. From that point on, about half of the robins alive in any year will make it to the next. Despite the fact that a lucky robin can live to be 13 years old, the entire population turns over on average every six years.

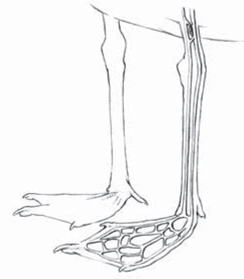

Q Why don’t birds fall off branches as they sleep?

A When a bird bends its legs to perch, the stretched tendons of the lower leg automatically flex the foot around the branch and lock it in place. This involuntary action is called “the perching reflex.”

Q How do birds stay warm all winter, especially when the temperature is below zero?

A Bird bodies are like a well-insulated cabin. Their outer, or contour, feathers keep moisture and wind out. Their inner, or down, feathers trap air, providing insulation to hold their body heat inside. Northern birds grow additional down feathers during the fall as temperatures start plunging. When they sleep, they raise these feathers, maximizing their insulation just as we do when we plump up a down sleeping bag or jacket.

Even the most well insulated cabin can be darned cold without a heat source within. Birds have two “furnaces” — their own muscle activity and their metabolism. Both burn calories from their food to produce heat. Birds can survive northern winters only if they can get enough high-energy food to maintain their body temperature. This is especially tricky because the farther north they are, the longer the nights, so the less time each day can be spent searching for food to stay alive over the long night.

On cold nights, roosting chickadees “turn their thermostat down” by allowing their body temperature, normally above 100°F (38°C), to drop to as low as 82° (28°C). This saves energy, just as we do when we turn down the thermostat in our house or apartment. When a chickadee awakens on a cold winter morning, it immediately starts to shiver. That muscle activity quickly raises its body temperature back to normal.

Another strategy that some species use to survive long winter nights in the far north is to cozy up to one another. Chickadees don’t do this — each one sleeps in its own cavity — but bluebirds, creepers, and Pygmy Nuthatches sometimes do.

Redpolls have more rods in their retinas than do many songbirds, allowing them to see better in dim light. They start feeding before dawn and continue to eat voraciously after sunset. They also have well-developed pouches along their esophagus, allowing them to load up on seeds at day’s end so they can stoke the metabolic fires through the night.

Q Why don’t birds get cold feet?

A Actually, songbirds do get very cold feet: the surface temperature of their toes may be barely above freezing even as the bird maintains its core body temperature above 100°F (38°C). But most birds don’t succumb to frostbite because there is so little fluid in the cells of their feet, and because their circulation is so fast that blood doesn’t remain in the feet long enough to freeze.

We don’t know if cold feet bother birds. We do know that they have few pain receptors in their feet, and the circulation in their legs and feet is a double-shunt — the blood vessels going to and from the feet are very close together, so blood flowing back to the body is warmed by blood flowing to the feet. The newly cooled blood in the feet lowers heat loss from the feet, and the warmed blood flowing back into the body prevents the bird from becoming chilled.

I’ve lived in northern Minnesota for over a quarter of a century, marveling at the winters. The coldest temperature ever measured in the state, –60°F (–51°C), was recorded in Tower, Minnesota, on February 2, 1996. Anticipating a record-breaker, one man slept out in a snow fort that night and emerged triumphant in the morning, clad in high-tech garb, to the cheers of hardy observers, TV cameras, and boom-microphones. No one seemed to notice the Black-capped Chickadees calling in the background. Each one of them had spent that record-breaking night sleeping outdoors, too, each alone in a small tree cavity, naked as a jaybird.

I’ve lived in northern Minnesota for over a quarter of a century, marveling at the winters. The coldest temperature ever measured in the state, –60°F (–51°C), was recorded in Tower, Minnesota, on February 2, 1996. Anticipating a record-breaker, one man slept out in a snow fort that night and emerged triumphant in the morning, clad in high-tech garb, to the cheers of hardy observers, TV cameras, and boom-microphones. No one seemed to notice the Black-capped Chickadees calling in the background. Each one of them had spent that record-breaking night sleeping outdoors, too, each alone in a small tree cavity, naked as a jaybird.