where the terms "citizen" and "citizess" (or "citess") had come into some vogue, but Chauncey Goodrich of Hartford would have no traffic with such foolishness, as he told Oliver Wolcott, Jr., the comptroller of the Treasury:

. . . Our greatest danger is from the contagion of levelism; what folly is it that has set the world agog to be all equal to French barbers. It must have its run, and the anti-feds will catch at it to aid their mischievous purposes. . . . before long the authors of entire equality will shew the world the danger of their wild rant. We treat their Boston notions with derision, and the name of citizen and citess, are only epithets of fun and joke; . . . a noisy set of discontented demagogues make a rant, and it seems as if they were about breaking up the foundations, but the great body of men of property move slowly, but move with sure success."

Such expressions were more characteristic of later opinion, however, than of the present spirit, even in New England.

Early in the new year, Jefferson, writing a private letter to William Short, now at The Hague, in the paternal tone which he had not yet laid aside, chided his former secretary for the "extreme warmth" with which the latter had censured the proceedings of the Jacobins in recent letters. He did this at the injunction of the President, he said, expressing the fear that if Short's criticisms became known they would injure him at home as well as abroad, since they would not be relished by his countrymen. This private letter contains as fervid comments as Jefferson ever made on the French Revolution, and it has been widely quoted by later writers for just that reason.^^

Jefferson's proneness to express himself more vehemently in private letters and memoranda than in public papers and official communications does not make him unique among human beings. Other responsible officers besides him have let themselves go in private while weighing their public words, though the reverse has often been the case with campaign orators — of whom he was never one. Whether the measured judgments of a responsible statesman or the unrestrained private language of the same man should be regarded as the better index of his true sentiments is perhaps an unanswerable question, and both must be taken into account by anyone seeking to arrive at truth, A statesman must be judged at last by his public policies and official acts, which represent the results of his sober deliberation, but private

17 Goodrich to Wolcott, Feb. 17, 1793 (Gibbs, I, 88).

18 TJ to Short, Jan. 3, 1793 (Ford, VI, 153-157), replying to a batch of letters, including a private one of Sept. 15.

language affords an important clue to the state of his own mind and emotions. The contrast was unusually sharp in the case of Jefferson, who imposed extraordinary restraint on himself as a public man while revealing the fervor of his nature in intimate circles and in personal memoranda. To hostile interpreters this apparent contradiction has lent color to the charge of duplicity, but Jefferson himself resolved it by harnessing his emotions (which actually were an essential element in his leadership) to the realistic and reasoned conduct of public affairs (which was his business). His friends could not have been unaware of his proneness to exaggeration when blowing off steam in private; and the persons most aware of it should have been his young friends, who stood in the position of disciples to him, for, like a teacher among his pupils, he was least inhibited and most likely to indulge in hyperbole with them. No saying can be fully understood out of its specific setting, and some of the most vivid of Jefferson's were pedagogical in purpose. These would not have endured had they not contained kernels of eternal truth, but the specific language was owing to particular circumstance. This letter to Short is a case in point. The essential and abiding truth embedded in it is that all human progress is costly, especially progress toward liberty and democracy; but much of its imagery is such as poets would use — not mathematicians or coldly calculating statesmen.

Jefferson's defense of the Jacobins, as a political party in France, need not detain us. Owing to the time-lag, his information about groupings and objectives could not be up to date, and he naturally read back into current struggles the issues he himself had perceived when, as a personal spectator of the revolution, he was better informed of developments than he could ever hope to be again. To him the Jacobins were merely the republican element in the old party of the Patriots, and the Feuillants (who had been discredited by this time) were the monarchical. His friend Lafayette had belonged to the latter group and he himself had been far from unsympathetic with its immediate objectives.^^ In later years he reasserted, in its most essential points, his original opinion. He said in his late seventies:

... I should have shut up the Queen in a Convent, putting harm out of her power, and placed the king in his station, investing him with limited powers, which I verily believe he would have honestly exercised, according to the measure of his understanding. In this way no void would have been created, courting the usurpation of a military adventurer [ Bonaparte 1 nor occasion

!• See Jefferson and the Rights of Man, ch. XII. Letters written him by Morris and giving fuller information about factional groupings had not yet been received.

given for those enormities which demoralized the nations of the world, and destroyed, and is yet to destroy, millions and millions of itsinhabitants.^"

But in the year 1793, when he was fifty, he believed that the experiment of retaining the hereditary executive, which he himself had favored at first, had failed completely and would have resulted in a return to despotism if it had been pursued. Thus he was now convinced that the "expunging" of the King had become an absolute necessity. By this he did not mean that the execution of Louis XVI was absolutely necessary, for at the time it had not occurred. What he did mean was that there was now an unavoidable choice between the revolution and the King. Gouverneur Morris had said practically the same thing, so the only real question was, which was preferable? Jefferson, who had never thought unkindly of this particular King and had given counsels of moderation to the Patriots while in France, had no possible doubt on that point. Being first of all a champion of liberty and popular sovereignty, he sympathized with this revolution, as he said ninety-nine one-hundredths of the American citizens did.

He was certainly not speaking with mathematical precision, but the celebrations of French military successes throughout the country that winter left no doubt that a large majority of the people did favor the Republic. Even Hamilton admitted this. He soon wrote to Short: "The popular tide in this country is strong in favor of the last revolution in France; and there are many who go, of course, with that tide, and endeavor always to turn it to account. For my own part I content myself with praying most sincerely that it may issue in the real happiness and advantage of the nation." ^^ The Secretary of the Treasury harbored real doubts, but even he veiled them in noncommittal language.

In private conversation, as Jefferson noted, John Adams was more forthright and more pessimistic. Adams was convinced that the temporary accession to power of successive revolutionary groups would be marked by the destruction of their predecessors, and that in the end force would prevail. He was quite cynical about it, saying that neither virtue, prudence, wisdom, nor anything else was sufficient to restrain human passions, and that government could be maintained only by force.^^ Like Jefferson, Adams was prone to exaggerated statements, indulging in them in public as well as private to the confusion

20 In autobiography (Ford, I, 141).

21 Hamilton to Short, Feb. 5, 1793 (Lodge, VIII, 293). Because of the f>art played by Short in financial transactions in Europe, Hamilton had extensive correspondence with him.

22 Note of conversation by TJ, Jan. 16, 1793 (LC, 13890).

of Others regarding his actual philosophy of a balanced government, but he showed remarkable prevision regarding the course of events in France. Later developments there were to shake though never to destroy Jefferson's faith in the essential reasonableness of most men, and it is a notable fact that his faith lived on in times of greatest darkness. At the moment, however, he was in line with the predominant opinion of his countrymen. He indulged to some degree in what in our own day is called "rationalization," but he was on strong ground when he pointed out to Short that the logic of the events was inescapable.

Short needed comfort, however, more than logic. The personal cost of the revolution was mounting, and the human toll was being taken among the very people whom he and Jefferson had valued most during the latter's stay in France. Lafayette, who had abandoned the revolution, was now in custody, and the liberal-minded Due de La Rochefoucauld had been snatched from his carriage and killed before the eyes of his old mother and young wife.^^ Of all the tragic events, it was this latter one that affected Short the most and that served most to embitter him. Jefferson did not yet have as full a tally of horrors as Short had, and he had been spared personal observation of them, but he was well aware of the general trend when he sought to bring philosophy to bear on these fearful developments.

... In the struggle which was necessary [he said], many guilty persons fell without the forms of trial, and with them some innocent. These I deplore as much as any body, & shall deplore some of them to the day of my death. But I deplore them as I should have done had they fallen in battle. . . . The liberty of the ivhole earth ivas depending on the issue of the contest, and ivas ever such a prize ivon with so little imwcent blood? My own affections have been deeply wounded by some of the martyrs to this cause, but rather than it should have failed, I would have seen half the earth desolated. Were there but an Adam & an Eve left in every country, & left free, it would be better than as it now is.24

23 Sec Jefferson and the Rights of Man, pp. 149-150, 210, 235, for the association of Short and Jefferson with this liberal nobleman and his family. It is not certain that TJ knew of his death when he wrote Short on Jan. 3, 1793. Morris reported it in a letter of Sept. 10, 17^2, which TJ received Jan. 10, 1793. Short's failure to mention it in his letter of Sept. 15, 1792 (received Jan. 2, 1793) and in letters of Oct. 9 and 12, 1792 (actually received in December) suggests that he was avoiding the painful subject. It seems probable, nonetheless, that TJ had received this gruesome piece of news in some other way, and the tone of his letter strongly suggests that he had.

2-* Ford, VI, 154, italics inserted.

In the last two sentences Jefferson indulged in hyperbole, and his words have inevitably been quoted, through the years since they have become known, because of their vividness. They are far more extravagant than the equally famous utterance of his to another young friend, William S. Smith, in a private letter relating to the Shays Rebellion in Massachusetts: "The tree of liberty must be refreshed from time to time with the blood of patriots and tyrants." ^^ While that saying has been tortured by later interpreters who have quoted it out of context, its essential truthfulness cannot be questioned by anyone familiar with the course of human history. The expressions to Short are another matter. The annihilation of a large portion of the human race in order that the few survivors may have the full enjoyment of liberty cannot be justified on either historical or philosophical grounds; and the record of Jefferson's reasoned and disciplined life gives every ground to suppose that he himself would have recoiled from such a holocaust. He would certainly have said no such thing in public, and he could hardly have been expected to anticipate that private words of his would be quoted to schoolboys in later generations, seized upon by political partisans, or exploited by reckless demagogues.

In writing to one whom he regarded as a son he let his poetic imagery run away with him, while stating what he regarded as essential truth. The heart of his message lies in the sentence we have italicized: ''The liberty of the whole world was depe?iding on the issue of the contest, and was ever such a prize won with so little innocent blood?'''' In terms which should be understandable in any society threatened by any form of political absolutism, he was saying that despotism had been overthrown in France; that, therefore, it would eventually be overcome everywhere; and that in the light of this vast triumph for the cause of human liberty the losses must be regarded as slight. He afterwards had to revise the casualty lists upward, but he was prepared for that; and the abiding significance of his reflections lies in his frank recognition that the cost of liberty may be and frequently is exceedingly high. When the times were much less troubled he had written Lafayette: "we are not to expect to be translated from despotism to liberty in a feather-bed." ^^ This lifelong champion of freedom could not lay first emphasis on security. The tragedy of French developments, as he later perceived it, lay less in their bloodiness, though that was bad enough, than in the fact that they led to

25 Ford, IV, 467; see Jefferson and the Rights of Man, p. 166. 2* Apr. 2, 1790 (Ford, V, 152).

new despotisms which seemed to confirm the pessimism of John Adams rather than his own optimism. But the counter-revolutionaries as well as the revolutionaries deserve blame for that, and at this stage the balance sheet seemed to show far more gain than loss.

At the moment, also, he was rejoicing that foreign developments were helping the cause of republicanism in his own country. He wrote Short that the triumph of republicanism in France had given the coup de grace to the prospects of the monocrats in America. A few days later, he wrote his son-in-law that the outcome of the revolution in France was now little doubted, and that the sensation that had been created in the United States by the establishment of the Republic showed that the ultimate form of the American government depended far more on events in France than anybody had previously imagined.-^ By now he more clearly recognized the unity of the Atlantic world. Speaking of his own country, he said: "The tide which, after our former relaxed government [the Confederation], took a violent course towards the opposite extreme, and seemed ready to hang every thing around with the tassels and baubles of monarchy, is now getting back as we hope to a just mean, a government of laws addressed to the reason of the people, and not to their weaknesses." Thus he believed that the revolution in France had checked the incipient counter-revolution in America, which would have turned back the political clock.

As for Europe itself, he soon got from John Adams's son-in-law later and more encouraging reports than he had had from William Short and Gouverneur Morris. Writing him from New York, early in February, William S. Smith said:

I left Paris on the 9th of November & have the satisfaction to inform you, that your friends there are well, and pursuing attentively the interests of that great & rising Republic, which notwithstanding the immense combination against them, I doubt not will be finally established, & the principles which gave it birth will expand and effect [sic] more or less every European state.^*

When Smith came to Philadelphia, later in the month, he brought Jefferson fresh information about the hostile attitude of Gouverneur Morris toward the current French government.^'* The Secretary of State already knew a good deal about that. He had received from Morris himself copies of the latter's correspondence with the French Minister of Foreign Affairs, Le Brun, which indicated strained rela-

27 TJ to TMR, Jan. 7, 1793 (Ford, VI, 157).

28 W. S. Smith to TJ, Feb. 8, 1793 (LC, 14106). 2»Feb. 20, 1793 (Ford, I, 216-217).

tions; and the documents seemed so delicate that Jefferson, rather than let them go through the hands of a clerk, did the necessary translation himself before transmitting them to Washington, though the task took him nearly all day.^" Philip Freneau, whose main business was editing the National Gazette, was still the translating clerk in the Department, but Jefferson kept these confidential documents out of his hands. He did not want the troubles bet\veen A4orris and the French ministry to be bandied about in the American newspapers.

This correspondence showed that Morris had asked for his passport, because he did not like the tone of a letter from Le Brun to him. The manners of the present French officials were certainly not up to those of Vergennes and Montmorin, with whom Jefferson had dealt; they deserved a rebuke and treated Morris better after they got it. Furthermore, their importunity in this instance was definitely connected with financial matters with which, actually, Morris had nothing to do. These were being handled by William Short and events proved that he was not blamable. But the French minister described the situation in language which Jefferson undoubtedly approved. After reminding Morris that the French government had done business with and given aid to the Americans before the government of the latter had "any solid existence," Le Brun said:

Before your Revolution, we had a Government which has always subsisted since. It is true, it has assumed another form; but liberty, the salvation of the country, have thus determined its creation. Besides, you, sir, who are bom in the midst of a free people, should consider the affairs of France under another point of view than that of all the foreign ministers residing in Paris. We support the saine cause as that of your coimtry: the?! our principles and yours should be the same, and, by a series of natural consequences, no reason can be opposed to your residence at Paris.^^

As he translated this passage, Jefferson's mind could hardly have failed to emphasize the words we have italicized, for they represented his own conviction. Morris himself had concluded that he would remain in France, though he wanted a passport into the interior, and he had told Le Brun what he had already told Jefferson. He said: "I have never doubted the right which every people have of forming, to themselves, such government as they please." ^^

30 TJ to Washington, Jan. 13, 1793 (LC, 13985), sending correspondence between Morris and Le Brun, Aug. 30-Sept. 17, 1792 (.A.S.P.F.R., I, 338-340).

31 Sept. 16, 1792; A.S.P.F.R., I, 339, italics inserted.

32 To Le Brun, Sept. 17, 1792 (A.S.P.F.R., \, 340),

Being the representative of a government which had begun its existence in a revolt against a king, he could have consistently taken no other position, but there was no possible doubt of his strong personal dislike of the present French officials, and Jefferson soon learned more of their discontent with his conduct. Ternant turned over certain extracts from their correspondence with him and Jefferson left in his own files translations of these which he himself must have made.^^ One of these officials said of Morris: "His ill will is proved. It is vain that he conceals it under diplomatic forms, which cannot be admitted between two nations who will not submit their liberty to the dangers of Royalty. In this point of view, the Americans of the United States are our brothers, and their Minister , . . betrays them as well as us." Colonel William S. Smith, just back from France, had refused to serve as an official channel of complaint, but he told Jefferson privately that the French ministers had entirely shut their doors to Morris and would receive no further communications from him. It is not to be supposed that these revolutionists were reasonable, but, on his part, Morris was most undiplomatic. In the presence of company at his own table and in the hearing of servants he had cursed the French ministers as "a set of damned rascals" and said that the King would be restored. His own diary shows that he was conniving with the royalists, and he expected to be recalled, believing that the French had asked it.^*

They had not asked his recall in so many words, but Washington himself did not see how Morris could be continued.^^ Perhaps he would not have been if the President had been able to make a more desirable arrangement. He raised sound objections to Jefferson's suggestion that Morris change places with Thomas Pinckney in London, believing that the French would not be satisfied by his transfer to that post. The President then suggested that if Jefferson was really determined to retire as secretary of state, the best possible arrangement would be for him to go to France for a year or two. The moment was important and, possessing the confidence of both sides, he might do great good. Jefferson would not hear of this, however. He was looking forward to real retirement, and he had no intention of ever crossing the

33 Documents dated Sept. 13-19, 1792 (LC, 13376-13377).

34 TJ's memo, of Feb. 20, 1793 (Ford, I, 216-218).

35 M.D. Conway in Ed?nund Randolph (1888), p. 149, quotes the Attorney General as arguing (Feb. 22, 1793) against Morris's dismissal. Randolph's assertion that the charges against Morris had come in an "ambiguous form, half-private, half-public," must be harmonized with the extracts from Ternant in TJ's files. The charges were official enough; though, as Randolph said, there was a real question how far the French themselves intended to press them. Furthermore, the difficulties of Morris's position must not be minimized.

Atlantic again. He had been lucky on his past voyages but he was an exceedingly bad sailor. Furthermore, he said, there was a better chance for him to do good in America, since the French were sending a new minister, armed with sufficient powers. He knew from Smith that Edmond Charles Genet was coming to replace the unhappy Ternant; and, fortunately for his own peace of mind, Jefferson did not anticipate the vast trouble the new envoy would cause.

It was through Smith that Ternant himself first learned of his pending replacement. The news took the edge off the financial negotiations that this faithful public servant was carrying on. In February, on the receipt of instructions from home which he wished he had had sooner, Ternant applied for a payment of three million livres ($544,500, according to Jefferson) on the American debt to his country; the money was to be expended in the United States for provisions to be shipped to France.^" In connection with this application, Jefferson expressed to Washington some of his doubts about the legality of Hamilton's fiscal operations to which we have already referred — particularly the diverting of the foreign fund to domestic uses.^" He may have thought that Hamilton would claim that the necessary funds were unavailable, and, if so, he was prepared to ask why.

When the whole matter was referred to the executive council, however, it proved uncontroversial. The Secretary of the Treasury estimated that the arrears due France to the end of 1792 amounted to about $318,000, and he himself thought that no more than that should be furnished, though the law permitted the President to anticipate payments on the French debt if he saw fit. Hamilton stated that the whole sum could be provided, within periods that would answer the purposes of the application, without deranging the Treasury. Whereupon the others expressed the opinion that the whole amount should be furnished, and Washington accepted their judgment. Acting through Jefferson, he authorized Ternant to make the necessary arrangements with Hamilton. These were to comport with the state of the Treasury, however, and the times of payment were thus left in Hamilton's hands.^*^ Ternant had to do his negotiating henceforth with the Secretary of the Treasury. He showed some vexation about the probable delays, but, judging from his official letters home, he did

38 Ternant got his instructions Feb. 7, 1793, and made his request next day (C.F.M., pp. 170, 173). He kept quiet about Morris at first, in order not to endanger his negotiations.

•" Notes sent Washington, Feb. 12, 1793 (Ford, VI, 175-179); see ch. 2, above.

3S Washington to Tj, I'eb. 26, 1793 (Fitzpatrick, XXXII, 360); TJ to Ternant, Feb. 25, 1793 (LC, 14195); "Cabinet Opinion" of Feb. 25, 1793 (Ford, VI, 190).

not prefer Jefferson to Hamilton at this or any other time. As he had reported the attacks on the Treasury in Congress he had appeared sympathetic with Hamilton, rather than with what he called the "popular party." Within a month, Jefferson suspected that Ternant was a royalist at heart and that a "connection" between him and Hamilton was springing up.^^

It is very likely that relations between the Secretary of the Treasury and the French envoy were more cordial now that the latter was out of favor with the revolutionary leaders at home, but on grounds of official policy toward France there was no serious rift within the administration as Washington's first term drew to a close. Friendship for the old monarchy had been transferred to the new republic in the Old World; and, up to this point, that friendship had been maintained.

38 TJ to Madison, March, 1793 (Ford, VI, 193).

C>v3

Peaceful Intentions in a World of War

AS THE time approached when he must take the oath of office for /jl a second time, the President, who had no precedent to guide him beyond the one he himself had set under rather different circumstances, was in doubt about the proper procedure. Therefore, late in February, 1793, he asked his department heads and the Attorney General to meet and give him their judgment. Hamilton was not there, but he had expressed the opinion that the oath should be administered in the President's own house. The Secretary of the Treasury, though the major champion of power in the government, was indifferent to mere trappings, and he regarded a private ceremony as safer. Randolph and Knox held that the oath should be taken in public, the big Secretary of War arguing for parade. Hamilton afterwards acceded, with some reluctance, to their recommendation that the ceremony take place in the Senate chamber and be open to the public. Jefferson concurred in Hamilton's original opinion, for reasons of his own.^ If his colleague's fears of disorder and the instability of the government were extreme, his own reaction against pretentious formalities had carried him farther than there was any real need of going. The Secretary of State craved republicanism that was pure and unadorned. Only in his desire to house the new government in splendid public buildings, such as were being planned for the Federal City beside the Potomac, did Jefferson manifest any interest in impressive symbols. He did not want to surround the highest office with majesty, believing that George Washington did not need it and that the great man's successors might take advantage of unwise precedents. Monarchy had become a phobia with him in a time when France was un-

1 Washington's letter of Feb. 27, 1793 and editor's note (Fitzpatrick, XXXIl, 361); TJ's memo, of Feb. 28 (Ford, I, 221-222); Cabinet Opinions, Fob. 27, Mar. i, '793 (JC.H., IV, 342-343).

doubtedly threatened with counter-revolution, and he appeared here as a doctrinaire formalist in reverse.

He had lost none of his faith in the American people, however, and none of his confidence in the unanimously re-elected President. He was now disposed to absolve Washington from responsibility for the levees, which he himself regarded as a silly and dangerous aping of foreign courts. About this time he recorded a story he had heard about the part played in the very first one by the President's pompous aide, David Humphreys. According to this, the doors were thrown open and Humphreys, in a loud voice, announced "the President of the United States" to the five or six gentlemen who had assembled. The General did not recover his composure throughout the levee, and afterwards he said: "Well, you have taken me in once, but by God you shall never take me in a second time." ^ Jefferson appears to have noted this episode because he found it reassuring, not because he thought it amusing.

Judging from contemporary accounts, the impressiveness of the second induction of the "beloved and venerable" George Washington on Monday, Anarch 4, 1793, was owing to the innate dignity and characteristic elegance of the man himself, rather than to adventitious ceremony. He had convened the Senate in special session to attend to certain matters touching the public good, and he rode alone in his own carriage to its chamber in Congress Hall. There he took his seat in the chair usually occupied by the president of that body. John Adams was now seated at the right and in advance of him, while Justice William Gushing had a corresponding position on the left. Upon hearing the announcement of the Vice President that the Justice was present and ready to give the oath, Washington arose. It was afterwards said that he was dressed "in a full suit of black velvet, with black silk stockings and diamond knee-buckles," that he carried a cocked hat and wore a light dress sword. He was always fastidious in his dress but he did not dazzle this assembly very long. Besides taking the oath, he made a speech of four sentences, saying that he would make another on a more appropriate occasion.

The heads of departments were there, though Jefferson does not appear to have mentioned it, as were foreign ministers, such members of the House of Representatives as had remained in town, and as many spectators as could be accommodated in the hall. On his return, the President was preceded by the district marshal and the

2 Memo, of Feb. 16, 1793 (Ford, I, 216), recording story of Edmund Randolph. This was confirmed years later by Madison, who was ][)resent (Journal of Jared Sparks, recounting visit in 1831, Harvard Univ. l,ib.).

I

PEACEFUL I N I E N T I O N S IN A WORLD OF WAR 57

county sheriff with their deputies, who had been gathered to prevent disturbance and constituted the only physical protection that the great man had. It was an "extremely serene" day; for, as a newspaper said, "Providence has always smiled on the day of this man, and on the glorious cause which he has ever espoused, of LIBERTY and EQUALITY." The occasion may not have satisfied the Secretary of War, since there was so little parade, but it ought to have pleased the Secretary of the Treasury and the Secretary of State. The President was safe — still sacrosanct, and the bare ceremony had no splendor save that his presence gave it.^ One spectator observed that the portraits of the King and Queen of France were covered. Trouble was coming to everybody from their direction, though the President does not appear to have anticipated this when he left Philadelphia for Mount Vernon toward the end of the month, taking with him three servants, including two postilions, and eight horses.*

According to Jefferson the rising of Congress was a joyful event, since it afforded some relaxation to everybody in the public business. Also, the unusual mildness of the season was pleasing to him, but he had to spend a vast lot of time catching up with his correspondence, and he viewed his situation with no satisfaction. Toward the end of March he wrote: "I am in truth worn down with drudgery, and while every circumstance relative to my private affairs calls imperiously for my return to them, not a single one exists which could render tolerable a continuation in public life." ^ He was going to continue for a time, nonetheless, and he had to find a place to live. He did not need a big one, for Maria who was in school, boarding with Mrs. FuUerton, was with him only on holidays. The state of her health disturbed him somewhat that spring. She was troubled with little fevers, nausea, and loss of appetite — from a weakness of the stomach, the doctor thought. It had been expected that her cousin Jack Eppes would go with the

3 For the ceremony, see Annals, 2 Cong., pp. 666-66-j; W. S. Baker, Washington after the Revolution (1898), pp. 251-253, quoting Dunlap's American Daily Advertiser, Mar. 5, and a contemporary letter; Fitzpatrick, XXXII, 374-375. The more glowing account in Scharf & Westcott, Hist, of Philadelphia, I, 473, appears to be based on recollections. Washington made a longer speech to the 3rd Congress, Dec. 3, 1793.

4 He left Philadelphia iMar. 27, 1793 (Fitzpatrick, XXXII, 4047/.; see also 413-414). His nephew, George Augustine Washington, had died a few weeks before and he held funeral services in his memory while at home. As we shall see hereafter, he started back on April 13.

5TJ to Col. David, Mar. 22, 1793 (LC, 14384). His comments on the rising of Congress were made in a letter to Martha, Feb. 24, 1793 (Edgehill Randolph Papers, UVA). His Index to Letters for March shows that he wrote in that month almost a hundred of them.

American commissioners to the big Indian council, but the state of the finances of Francis Eppes dimmed that prospect and the boy went home instead. The main trouble was that an expected judgment in favor of the Wayles estate had not materialized and there was uncertainty whether there would be any ready cash from it anyway. This delay also embarrassed Jefferson, who had a share in the claim, and it was one of the complications in his personal affairs that made him wish that he could go home.^

The house he took was a little way in the country, on the Schuylkill near Gray's Ferry and within sight of Bartram's and Gray's Gardens on the other side of the river. He agreed with the owner, Moses Cox, to take it at the beginning of April, and he moved in a little before his fiftieth birthday.'^ He sent several loads of his books to the country, but shipped others to Virginia, along with his surplus furniture. Upwards of fifty packing cases were put aboard the good sloop Uriion, bound for Richmond, where he expected them to be stored temporarily in a warehouse. He figured that his goods would fill a room, and that the packages containing looking glasses would have to remain in Richmond until the next winter, since they must go thence to Albemarle by water. The season had been dry as well as mild, hence the rivers at the time were low.® Meanwhile, he had had certain repairs made in the house of Thomas Leiper which he was vacating, and just before he left he got the consent of the new tenant for his coachman's wife to remain a little longer. Happening to "lay in," she could not yet be removed with safety.^

He was not sure just how long he would stay on the banks of the Schuylkill, but he regarded the end of the summer as the outside limit and hoped to get away much earlier. In May he was "in readiness for flight" as soon as he could find "an apt occasion," and he tried to make it clear that when he did leave the government it would be for good. Writing his son-in-law, who had recently bought a horse for him, he said: "My next return to Monticello is the last long journey I shall ever

®TJ to Martha, Apr. 8, 1793 (copy, Edgehill Randolph Papers, UVA); Francis Eppcs to TJ, Alar. 6, 1793 (ibid.); Account Book, Feb. 20, 1793, showing payment of $80 to Airs. Fullerton for six months' board for Maria. The case was that of Gary's executor, which kept recurring in TJ's correspondence during the rest of his stay in Philadelphia.

■'TJ to Cox, Alar. 12, 1793 (LC, 14287); see also TJ to Martha, Mar. 10 (Randall, II, i9i);TJtoCox, Alar. 7 (LC, 14252).

8 Various items in Account Book, Apr. 6-9, 1793, show payments for "portage" of books and furniture. He wrote James Brown in Richmond about the shipment. Apr. 7 (copy, Edgehill Randolph Papers), and got a shipping receipt for 50 casei and I bbl. on Apr. 9 (LC, 14499).

8 TJ to Thomas Leiper, Apr. 11, 1793 (LC, 14511).

J

PEACEFUL INTENTIONS IN A WORLD OF WAR 59

take, except the last of all, for which I shall not want horses." ^^ He did not get home as soon as he expected, but he got himself into the countryside anyway. Maria's health improved somewhat and she spent Sundays with him. When hot weather came he practically lived outdoors — eating, writing, reading, and receiving his company beneath the plane trees.^^

In the middle of March the Secretary of State wrote his old friend, Dr. George Gilmer of Pen Park in Albemarle County, that there had been no news of France since the beginning of the King's trial.^- He did not know that Louis XVI had been seven weeks dead. But he and Washington had enough knowledge of the plight of Lafayette to be deeply troubled about that, and before the President left for Mount Vernon they did what little they could for him.

The turn of events with respect to the Marquis was ironical in the extreme. Early in the previous summer, Jefferson, who had known him so intimately in Paris, had addressed him thus: "Behold you, then, my dear friend, at the head of a great army, establishing the liberties of your country against a foreign enemy. May heaven favor youf cause, and make you the channel through which it may pour its favors." Employing the extravagance of language he allowed himself in private letters, he spoke of his old friend as "exterminating the monster aristocracy, and pulling out the teeth and fangs of its associate monarchy." This letter had not reached Lafayette when that liberal nobleman deserted the revolution and fled to Belgium, where he fell into the hands of the Austrians. In fact, he did not get it until after he emerged from prison some six years later.^^ Gouverneur Morris promptly reported that he had "taken refuge with the enemy," though this letter did not reach the Secretary of State much before the end of the year. "Thus his circle is completed," wrote the American minister. "He has spent his fortune on a revolution, and is now crushed by the wheel which he put in motion. He lasted longer than I expected." i'*

Early in 1793, Washington, without any solicitation, had deposited in Amsterdam 200 guineas to be subject to the orders of the Mario TJ to TMR, May 19, 1793 (LC, 14864); TJ to J. W. Eppes, May 23, 1793 (Ford, VI, 264).

11 TJ to Martha, May 26, July 7, 1793 (Ford, VI, 267; Randall, II, 191-192).

12 Mar. 15, 1793 (Ford, VI, 202).

13 To Lafayette, June 16, 1792 (Ford, VI, 78); from Lafayette, Nov. 20, 1800 (LC, 18846).

!■* Morris to TJ, Aug. 22, 1792 (A.S.P.F.R., I, 336). Lafayette deserted on Aug. 19, and TJ acknowledged this letter on Dec. 30, 1792.

quise — stating that he owed her husband at least that amount for services that had been rendered him but for which no account had ever been received.^^ Afterwards he heard from her and was somewhat reassured about her personal situation, though still at a loss about what, if anything, he could do for her imprisoned husband. At length Jefferson, on Washington's instructions, asked Morris to procure Lafayette's liberation by informal solicitations if possible, and to use formal ones if these should seem desirable. Also, he assumed the difficult and delicate task of drafting the letter which Washington sent to the Marquise. "My affection to his nation and to himself are unabated," said the President in the Secretary of State's language, "and notwithstanding the line of separation which has been unfortunately drawn between them I am confident that both have been led on by a pure love of liberty, and a desire to secure public happiness, and I shall deem that among the most consoling moments of my life which should see them reunited in the end, as they were in the beginning, of their virtuous enterprise." ^^ The words were those of a friend of the man himself and also of the revolution which had engulfed him, and if they voiced the sentiments of Jefferson they were subscribed to by Washington. They had hardly been written when news reached Philadelphia that Louis XVI had been executed by the guillotine.

The death of the King was generally regretted by Americans, but the shading of opinion — between sorrow and anger — tended to conform to domestic political complexions. Jefferson noted this fact, but informed Madison that the execution had not produced as open condemnation from the "Monocrats" as he had expected. The ladies of the first social circle in Philadelphia were "all open-mouthed against the murderers of a sovereign" but their husbands were more cautious.^'^ Even Oliver Wolcott, Jr., whom Jefferson placed on the extreme right wing, expressed himself with restraint. Sending his father a paper containing "an account of the fate of poor Louis," he mildly said: "It remains to see the result of the great experiment which the French are attempting." Chauncey Goodrich of Hartford spoke of the execution as "a wanton act of barbarity, disgraceful even to a Parisian mob," adding that it threatened the success of republicanism in France — a thing which he himself did not approve of. It

15 Washington to the Marquise de Lafayette, Jan. 31, 1793 (Fitzpatrick, XXXII, 322).

i« Washington to TJ, Mar. 13, 1793 (Fitzpatrick, XXXII, 385-386); TJ to Morris, Mar. 15, 1793 (Ford, VI, 202-203); draft of letter to Madame de Lafayette, Mar. 16, 1793 (Ford, VI, 203-204); letter as sent to Marquise de Lafayette, Mar. 16, 1793 (Fitzpatrick, XXXIf, 389-390).

'■^ TJ to Aladison, Marcli, 179^ (Ford, VI, 192-193).

J

might be expected to serve a good purpose in America, also — by-checking "the passions of those who wish to embroil us in a desperate cause, and unhinge our government." ^^

At the other extreme was an anonymous writer in Freneau's National Gazette who entitled his article: "Louis Capet has lost his caput." This author said: "From my use of a pun it may seem that I think lightly of his fate. I certainly do. It affects rne no more than the execution of another malefactor." ^^ Jefferson himself would not have been in character if he had descended to such unbecoming levity, and, as a matter of fact, he left in the record very few contemporary comments on these events. In later years, while still declining to sit in historical judgment on the executioners of the King, he skillfully-summed up their arguments and made clear his personal disagreement with theuL Toward the end of his life he wrote:

... I am not prepared to say that the first magistrate of a nation cannot commit treason against his country, or is unamenable to its punishment; nor yet that where there is no written law, no regulated tribunal, there is not a law in our hearts, and a power in our hands, given for righteous employment in maintaining right, and redressing wrong. Of those who judged the king, many thought him wilfully criminal, many that his existence would keep the nation in conflict with the horde of kings, who would war against a regeneration which might come home to themselves, and that it were better that one should die than all. / should not have voted "with this portion of the legislature.^^

At the moment, however, this peace-loving man who laid such store by orderly constitutional processes seems to have harbored no doubt that monarchs were "amenable to punishment like other criminals"; and, despite his generally charitable judgment of L-ouis XVI as a human being, he was wasting no sympathy on an ill-advised King, when more innocent men than he had died.^^ He might well have suffered a revulsion of feeling if he had been in France in early 1793, just as Thomas Paine did, but he still believed that the liberty of the whole earth depended on the issue of the contest. Nor was he any less aware than Alexander Hamilton of the possible repercussion of these events on the American public mind.

Reporting to him a little later about Virginia, James Monroe said: "I

18 Oliver Wolcotr, Jr., to Oliver Wolcott, St., Mar. 20, 1793; Chauncey Goodrich to Oliver Wolcott, Jr., Mar. 24, 1793 (Gibbs, I, 90). See also Oliver Wolcott, Sr., to his son. Mar. 25, 1793 {ibid., p. 91).

1^ National Gazette, Apr. 20, 1793.

-f* in his autobiography (Ford, I, 141), italics inserted.

-1 To an unknown person, Mar. 18, 1793 (L. & B., IX, 45).

scarcely find a man unfriendly to the French revolution as now modified. Many regret the unhappy fate of the Marquis of Fayette, and likewise the execution of the King. But they seem to consider these events as incidents to a much greater one, and which they wish to see accomplished." 22 These reassuring words really amounted to a summary of Jefferson's own position. In its shading this judgment differed from one that Edward Carrington, a man of different political persuasion, gave Hamilton about these same Virginians. He said: "I believe the decapitation of the king is pretty generally considered as an act of unprincipled cruelty, dictated by neither justice nor policy. In my own mind, it was a horrible transaction in every view; and to an American, who can yield to its propriety, it ought to be felt as a truly sorrowful event." With respect to the cause of France, however, he believed that the general wish was for its success.-^ Meanwhile in Philadelphia, that friend of Thomas Jefferson and John Adams, Dr. Benjamin Rush, while deploring the act and praising the King rather more than he deserved, was saying that the noble cause in which France was engaged, "though much disgraced by her rulers, must finally prevail." ^*

About the time that George Washington went home to Amount Vernon, the father of the comptroller of the Treasury wrote from Hartford to his son: "I hope that the President will continually superintend the conduct of the Secretary of State, so as not to suffer by his indiscretion these states to be involved in the vortex of European politics." 25 Had this Connecticut Yankee been permitted to look over the shoulder of the Secretary of State when the latter was writing American representatives abroad at this very juncture he should have been reassured; though he would also have been deprived, at an early stage, of one of the most important of the allegations of Hamilton and his partisans. Late in March, Jefferson wTote prophetically:

. . . The scene in Europe is becoming very interesting. Amidst the confusion of a general war which seems to be threatening that quarter of the globe, we hope to be permitted to preserve the line of neutrality. We ivish not to meddle with the internal affairs of any country, nor with the general affairs of Europe. Peace with all nations, and the right which that gives us with respect to all nations, are our object. It will be necessary for

22 Monroe to TJ, May 8, 1793 (S.M.H., I, 252).

23 Carrington to Hamilton, Apr. 26, 1793 (J.C.H., V, 555).

2* To J. C. Lettson, Letters of Benjmnin Rush (1951), ed. by L. H. Butterfield, 11,635. 25 Oliver Wolcott, Sr., to Oliver Wolcott, Jr., Mar. 25, 1793 (Gibbs, I, 91).

PEACEFUL INTENTIONS IN A WORLD OF WAR 63

all our public agents to exert themselves with vigilance for securing to our vessels all the rights of neutrality, and from preventing the vessels of other nations from usurping our fiag.-^

Here is a major clue to the policy which Jefferson consistently pursued as Secretary of State, under much greater difficulties than he now anticipated, and here are some of the germs of the policy later pronounced by his disciple Monroe in his famous Doctrine. There is no point in arguing about the major credit for policies which were advocated by so many leaders in common, but these were wholly consistent with Jefferson's own past and represented a concern for the welfare of his own country which was relatively, if not wholly, independent of ideology. No one was more convinced than he that his country required peace and time to grow in. He had no thought of letting it be hitched to the war chariot of any other nation.

If there was any exception to his prevailingly peaceful intentions, it was with respect to Spain, the country that controlled the mouth of the Mississippi. He had instituted negotiations with the Spanish, but toward them he was not unwilling to sound bellicose.^^ At length his young friend William Short had joined William Carmichael in Madrid, where the two commissioners were destined to suffer long frustrations, and in the meantime new problems had arisen because of the activities of the Governor of Louisiana in connection with the Indians. When these were discussed in the executive council in the autumn of 1792, it was Hamilton who talked most of peace, and the Secretary of the Treasury even broached the matter of a British alliance. It was Jefferson who wanted to refer to Congress a recent Spanish communication, since the matter of declaring or not declaring war lay within their province. This is not to say that he himself wanted war, but he was prepared to consider it as a possibility. The Spanish letter was sent to Congress, and Jefferson wrote the American commissioners in Spain to make representations to the Spanish Court.-^

Nothing came of this business, and it is mentioned here chiefly to illustrate Jefferson's attitude toward the Spanish. This was largely owing to his continuing concern for the navigation of the Mississippi and his consciousness that Spain was a waning power which could be chalk :ged with relative safety by his own country, now growing

26 TJ to C. W. F. Dumas, Mar. 24, 1793 (L. & B., IX, 56), italics inserted. He wrote in the same vein to others.

27 See Jefferso?! and the Rights of MaJi, pp. 406-411.

28 Memo, of Oct. 31, 1792 (Ford, I, 205-207); TJ to Carmichael and Short, Nov. 3, 1793 (Ford, VI, 129-130). The communication from the Spanish commissioners in America, Viar and Jaudenes, was sent to Congress on Nov. 7 (A.S.P.F.R., I, 139). Short did not reach Madrid till Feb. i, 1793.

rapidly in strength on the western waters. The further weakening of Spain seemed so desirable to him that he welcomed later reports that the French purposed to free the Spanish colonies, and he instructed Carmichael and Short not to offer Spain any American guarantee of these. Previously, he had been willing to guarantee her possessions west of the Mississippi if she would cede those on the east, but the situation was now changed. He had intimations that the French would not object to the incorporation in the United States of the Spanish territories east of the great river, as he also had that the Spanish and British were now acting in concert. That concert was to become closer than he yet anticipated — for the old ally of Bourbon France entered into a formal British alliance before summer, thus eifecting a diplomatic revolution, shifting the balance of power in the New World as well as the Old, and causing the Spanish themselves to become more bellicose toward the Americans. This new alignment did not endear them to Jefferson the more, and it gave him a new reason for friendliness to France, but the point that calls for emphasis in the early spring of 1793 is that Jefferson was most likely to be belligerent on American questions — of which the security of the United States on its own continent was a major one. As a responsible statesman he had no thought of getting embroiled in European quarrels, regardless of personal predilections and ideology. From the beginning to the end he favored a policy of neutrality.^*

Within ten days of the execution of Louis XVI the European war, hitherto confined to the Continent, was extended to include Great Britain, the news being received in Philadelphia early in April. At the same time, Holland was drawn into it, as Spain was a few weeks later.^*^ It was now unquestionably a general war, and with the involvement of the colonial powers it embraced the entire Atlantic world of which the United States of America was a part. The difficulties wliich the young Republic faced were not merely such as

29 TJ learned of French designs against the Spanish colonies at least by Feb. 20, 1793, when he talked with W. S. Smith (memo, in Ford, I, 216-218). His change in the instructions to Carmichael and Short was made Mar. 23 (Ford, VI, 206), which was before he had heard of the beginning of war between France and Great Britain and considerably before he heard of the declaration of war on Spain by France. His intimations of the concert between Spain and Great Britain must have been received earlier, perhaps from Smith. The treaty of alliance between Spain and Great Britain (May 25) made the mission of Carmichael and Short more futile than ever, for at this point or earlier Spanish fears for Louisiana temporarily disappeared. On June 23, 1793, TJ wrote Madison that Spain was trying to pick a quarrel with the U. S. (Ford, VI, 316).

^Trance declared war on Great Britain and Holland on Feb. i, 1793; and against Spain on Murcii 7.

PEACEFUL INTENTIONS IN A WORLD OF WAR 65

would inevitably arise from conflicts on the seas where its commerce plied. The nation was allied by treaty with one of the contending powers, France, whose forces were now arrayed against the field. In the light of history, the conflict may be viewed as one between nations, for their respective advantages. It may also be described in terms of revolution and counter-revolution, for the countries opposing the French were trying to extinguish what threatened to become an all-consuming fire. Alexander Hamilton perceived this clearly from the start. Writing Washington, he said: "The present war, then, turns essentially on the point — What shall be the future government of France? Shall the royal authority be restored in the person of the successor to Louis, or shall a republic be constituted in exclusion of it?" ^^ There could be no question where Hamilton stood in this conflict between legitimacy and revolution, between ancient authority and emerging democracy, and there can be no doubt where Jefferson stood. The irrepressible conflict between the two men and their philosophies was now being waged on a larger front.

While neither man could remain a mere spectator or a philosopher in a tower, it would be unjust to describe one of them as pro-French and the other as pro-British. That was the language of political partisanship in that day and it has found its way into many works of history, but fairness to both of these eminent Americans requires that such terms should not be loosely used.^^ Of the two, Hamilton had been much more indiscreet in his relations with British representatives, especially George Hammond, who was still in the United States, than Jefferson had been in his dealings with Ternant, the French minister. Judging from the past, therefore, Hamilton might have been expected to be less mindful of the proprieties and more reckless in his approach to the problems of the hour. In spirit he was far more the military man and less the civilian than his great rival, and there were grave dangers in the bellicosity of his nature, as Jefferson realized and John Adams afterwards found out. But his national patriotism was unquestionable, and the success of his financial policies was contingent on the maintenance of peace.

In public, though not always in private, Jefferson was much more controlled, and, as he told John Adams at a time when a rupture with Great Britain seemed much more imminent, he had been through one war and did not want to face another.^^ More clearly than Hamilton

31 April, 1793 (J.C.H., IV, 365).

32 This matter is well stated by C. M. Thomas, American Neutrality in 77^5 (1931), pp. 14-15. I have benefited greatly from reading this study.

he perceived that the victors are punished in war, as well as the vanquished; and certain efforts of his in later years to attain national ends by nonmilitary means led him to be described as a pacifist, though he certainly was not that. He was fully aware of the need of his growing country for peace, and he had said already that the only real gainers from war were the neutrals. Ever since his own stay in Europe he had believed that the United States stood to gain from the distress and vicissitudes of the nations of the Old World. There was astute calculation in his public policy, and history was destined to substantiate his major hopes.^* But for the troubles in the Old World, the United States would hardly have picked up Louisiana and the Floridas so easily in later years. With respect to the interests of his own country, particularly its territorial interests, he was positively avaricious and at times sounded ruthless; but he relied on diplomatic methods and the assistance of external events even when, upon occasion, he rattled the saber or talked extravagantly behind the scenes. His benevolence toward the French cause at this stage may be assumed wholly apart from ideology, for he had long ago concluded — as indeed John Adams had — that France was the natural friend of the United States. This was true of the old monarchy and it seemed reasonable to suppose that it would be even truer of the new republic. Thus, unquestionably, he hoped for French victory. But he now believed that the United States could serve the French better as a neutral than as a belligerent. American armed might was small, but provisions were plentiful.

He regarded Great Britain as a natural competitor and rival and w as deeply suspicious of a government which, in his American opinion, had deliberately violated the treaty of peace and had certainly ignored the elaborate representations he had made to George Hammond.•''■■' That minister had gained his impressions of the Secretary of State's position from Hamilton as well as from his own rather humbling experiences. Writing home to his government, he had expressed the opinion that the United States would not go to war with Great Britain, but was dubious about Jefferson, believing the latter to be "so blinded by his attachment to France, and his hatred of Great Britain . . . that he would without hesitation commit the immediate interests of his country in any measure which might equally gratify his predilections and his resentments." ^'^ There can be no possible doubt that Jefferson

3< This point about TJ is strongly emphasized by S. F. Bemis in his writings. 35 See Jefferson and the Rights of Man, pp. 417-420.

3* Hammond to Grenvillc, Mar. 7, 1793, quoted from British State Papers b) Thomas, p. 22W. This was before he had learned of the declaration of war.

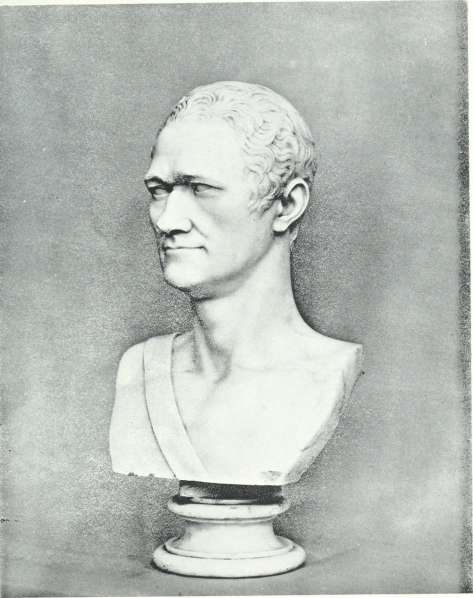

Courtesy of the Museum of the City of New York

Colossus in Marble

Bust of Haviilton by Giuseppe Ceracchi

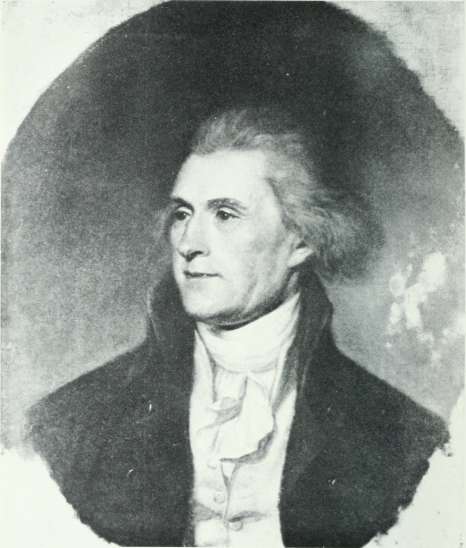

Courtesy of Indc-pcndence National Historical Park: Photograph by Peter A. Jiiley 6- Son

Jefffrsov \\fiiff Secretary of State

This porrniir by Charles Willson Peale, painted late in 1791, sii(n\ s his hi<4h color, hazel eves, and reddish hair

PEACEFUL INTENTIONS IN A WORLD OF WAR 67

resented the treatment that he and his country had received at tlie hands of the British government, but the zealous young minister's misinterpretation of him followed the Hamilton party line precisely and this fact could not have been wholly coincidental.

The President had first-hand knowledge of his Secretary of State. George Washington could hardly have been surprised, therefore, when Jefferson, in a letter announcing the extension of the European war, said that it was necessary "to take every justifiable measure for preserving our neutrality." About the same time Hamilton referred to "a continuance of the peace, the desire of which may be said to be both universal and ardent." ^" But peace and neutrality arc very general terms, and witliin the broad area of agreement there was abundant ground for disagreement regarding specific actions. If the patient President, who vie\\'cd this conflict with fewer predilections than either of his chief advisers, did not realize this already, he found it out soon after he got back to Philadelphia.

37TJ to Washington, Apr. 7, 1793 (Ford, VI, 212); Hamilton to Washington, Apr. 8, 1793 (J.C.H., IV, 357).

Cv3

Fair Neutrality in Theory and Practice

IF GEORGE WASHINGTON had any hopes of relaxing in the spring sunshine at Mount Vernon in early April, 1793, these were soon banished by the news from Europe. This was relayed by Hamilton as well as Jefferson; indeed, the ubiquitous Secretary of the Treasury wrote of the extension of the war a little sooner than his more prudent colleague.^ Nobody had been caught napping, however, and the President, after replying to his two chief assistants in similar language on one day, set out for the seat of government on the next.- In both letters he used the expression "strict neutrality," and he referred to reports that American vessels were already being prepared as privateers. There lay the immediate danger of unneutral actions. Washington wanted his advisers to give thought to any measures which should be taken.

Back in Philadelphia within a week, he promptly submitted to the Heads of Department and the Attorney General a set of questions, thirteen in number, asking them to be prepared to discuss these at a meeting at his house the first thing next day. The questions were in the President's handwriting, but Jefferson and Randolph believed they were largely drawn by Hamilton, as they almost certainly were.^ Because of patriotic or partisan zeal or both, the officious Secretary of the Treasury had seized the initiative in matters which directly

1 Hamilton to Washington, Apr. 5, 8, 1793 (J.C.H., IV, 355-356); TJ to Washington, Apr. 7, 1793 (Ford, VI, 212).

2 Both letters dated Apr. 12, 1793 (Fitzpatrick, XXXII, 415-416). In J.C.H., IV, 357, the letter to TJ is incorrectly designated as the one to Hamilton.

3 Washington got back Apr. 17 and submitted the questions Apr. 18, 1793 (Fitzpatrick, XXXII, 419-421). See TJ's memo, dated Apr. 18 and written May 6 (Ford, I, 226-227). Thomas (pp. 28-30) thinks that Hamilton was responsible for at least 12 of the 13. He had already consulted John Jay and received from him a draft of a proclamation; Jay to Hamilton, Apr. 11, 1793 (J.C.H., V, 552-553, and draft in HP, i ser., 19:2877).

FAIR NEUTRALITY IN T H F, O R Y AND PRACTICE 69

and more immediately concerned the Secretary of State. Also, he had caused some questions to be asked which, in Jefferson's opinion, should not have been raised at all.

Only two of the questions were answered at the first meeting at the President's house. It was unanimously agreed that a proclamation should be issued and that a minister from the French Republic should be received. The latter decision related to the newly appointed minister, Edmond Charles Genet, then en route, whom Washington, before he went away, had already decided to receive. Randolph and Hamilton had concurred in the decision, though the latter did so reluctantly.'* Hamilton's present argument was that the outbreak of war had introduced a new element, but this consummate and inveterate politician may have thrown the question into the hopper merely for bargaining purposes. He now yielded to the judgment of the others, as Jefferson did in the matter of the proclamation, and the surprising thing is that either man should have demurred at all.

Since Jefferson had already made it abundantly clear to Washington and others that he favored a policy of neutrality, his doubts related wholly to the desirability of a proclamatio?i and to its form and timing. His first objection was on the constitutional ground that a declaration of no war was as much beyond the competence of the executive as a declaration of war, which was clearly the prerogative of the legislative branch. In the light of Washington's later statement that "he never had an idea that he could bind Congress" ^ this sounds a good deal like legalistic quibbling. Jefferson soon agreed with his colleagues that the President should not summon Congress and thereby create alarm, but he suspected that Hamilton wanted to bind the future conduct of the country by executive act, pressing executive powers to their limit according to his custom.*'

What he himself really wanted was a declaration that the country was in a state of peace, in which it was the duty of the citizens neither to aid nor injure any of the belligerents. This state of peace would properly be preserved by the Executive until the constitutional authorities (Congress) should determine otherwise. He said afterwards: "The declaration [by the President] of the disposition of the United States can hardly be called illegal, though it was certainly officious and

^ TJ's memo, of Mar. 30, 1793, referring to earlier conversations (Ford, I, 224). Washington said he never had any doubts on the subject. He recommended that Genet should be received "not with too much warmth or cordiality," but TJ believed that this was a "small sacrifice" to the opinion of Hamilton.

^ TJ's memo, of Nov. 18, 1795 (Ford, I, 266-267).

^ His fears were largely borne out by Hamilton's Pacificus papers in the summer (Lodge. IV, 135-191); see below, pp. iio-ui.

yO JEFFERSON AND THE ORDEAL OF LIBERTY

improper." "^ He also said: "The instrument was badly drawn, and made the P. go out of his line to declare things which, though true, it was not exactly his province to declare." ^ His objections were met at the time, supposedly, by the omission of the word "neutrality" from the document. He soon noted, however, that the word was widely used anyway; and it has seemed to many writers since his time that he was making a distinction where there was little or no real difference. The pressure of circumstances would not allow, it seemed, for this degree of constitutional purism.

His second line of objection was that a proclamation would be premature, since the warring nations, and especially the British, would be willing to buy American neutrality by the sort of concessions he had long been vainly seeking. He did not like to surrender his bargaining power, and he clung to the beUef that he could have gained something. Some \\ eeks later he wrote Madison: "I now think it extremely possible that Hammond might have been instructed to have asked it [neutrahty], and to offer the broadest neutral privileges, as the price, which was exactly the price I wanted that we should contend for." Judging from Hammond's instructions, which we can read though Jefferson could not, such was not the case. No concessions of any sort were suggested in these, and the envoy was told to support the American friends of Great Britain, the chief of whom was unquestionably Hamilton.^ Jefferson left no possible doubt of his own opinion of his colleagues's attitude. Before long he wrote James Monroe: "Hamilton is panic-struck if we refuse our breach to every kick which Great Britain may choose to give it. He is for proclaiming at once the most abject principles, such as would invite and merit habitual insults." '°

Jefferson's initial wariness about the Proclamation cannot be separated from his inveterate and by no means unwarranted suspicions of the Secretary of the Treasury, and very likely there was in it an element of pique. But he fully recognized the necessity of warning American citizens against actions that were dangerous to them and to their country. For example, they must be told that they were not free to take sides with either belligerent and "enrich themselves by depredations on the commerce of the other." ^^ He believed that, while the

7 To iMadison, July 29, 1793 (Ford, VI, 328).

^TJ to Madison, Aug. 11, 1793 (Ford, VI, 369). See also TJ to Monroe, July 14, 1793 (Ford, VI, 346).

">* TJ to Madison, June 29, 1793 (Ford, VI, 328); Grenville to Hammond, Feb. 8 and Mar. 12, 1793 (/./i./V/., pp. 35, 37).

'*' TJ to iVlonroe, May 5, 1793 (Ford, VI, 238-239).

FAIR NEUTRALITY IN T H li O R Y AND PRACTICE 7 I

lure of easy profits was great, the desire for peace was practically universal. The day after the meeting at which he agreed to the issuance of a proclamation and two days before its signing, on April 22, he wrote to Gouv^erneur Morris in France:

. . . No country perhaps was ever so thoroughly against war as ours. These dispositions pervade every description of its citizens, whether in or out of Office. They cannot perhaps suppress their affections, nor their wishes. But they will suppress the effects of them so as to preserve a fair neutrality.^^

He himself did not hesitate to use the word "neutrality," for, indeed, there was no other so good to use. But he left no doubt of liis own affections for France and his wishes with regard to the outcome of this conflict. In his opinion, the enemies of that country were "conspirators against human liberty."

The drafting of the proclamation was left to Edmund Randolph, with Jefferson's obvious consent. The instrument was communicated to him after it was drawn, but he said later that all he did was run his eye over it to see that it was not a "declaration of neutrality." " He was then engaged in drawing an elaborate opinion on the French treaties, in opposition to Hamilton, which he probably regarded as a more important piece of business at the moment. It has been alleged that he avoided direct responsibility for the proclamation in order that he might be free to criticize it afterwards.^"* He did speak slightingly of it in his intimate political circle, though apparently nowhere else. Within a week, when writing Madison, he referred to the "cold caution" of the government and he later spoke to this friend of the "milk and water views" of the proclamation, even terming it pusillanimous.^^

In view of the fact that he, more than any other official, was charged with the enforcement of the policy of neutrality and that he was assiduous in his efforts throughout the rest of his term of office, this criticism seems to involve a contradiction. Here we have again a contrast between his public conduct and his private opinion. During the next few weeks this seems to have increased rather than diminished — as he learned more about the sentiment of the people and the views of his closest political friends, as he became increasingly im-

12 Apr. 20, 1793 (Ford, VI, 217).

13 TJ ro Madison, Aug. 11, 1793 (Ford, VI, 369). ^■* Thomas, p. 457?.

15 To Madison, Apr. :8, May 19, June 29, 1793 (Ford, VI, 232, 259, 328).

patient with Edmund Randolph and suspicious of Hamilton as an Anglophile. He regarded the policy as inevitable but regretted this damper on American enthusiasm for the cause of France. Very early he wrote iMadison: "I fear that a fair neutrality will prove a disagreeable pill to our friends, though necessary to keep out of the calamities of a war." ^^

To his political intimates it did seem that a bitter pill w^as being administered. "Peace is no doubt to be preserved at any price that honor and good faith will permit," wrote Madison from Orange, but he feared "a secret Anglomany" behind the mask of neutrality.^'' A little later Madison spoke much more strongly:

... I regret extremely the position into which the P. has been thrown. The unpopular cause of Anglomany is openly laying claim to him. His enemies masking themselves under the popular cause of France are playing off the most tremendous batteries on him. The proclamation was in truth a most unfortunate error. It wounds the national honor, by seeming to disregard the stipulated duties to France. It wounds the popular feelings by a seeming indifference to the cause of liberty. And it seems to violate the forms & spirit of the Constitution, by making the executive Magistrate the organ of the disposition, the duty and the interest of the Nation in relation to War & peace, subjects appropriated to other departments of the Government. It is mortifying to the real friends of the P. that his fame & his influence should have been unnecessarily made to depend in any degree on political events in a foreign quarter of the Globe; and particularly so that he should have anything to apprehend from the success of liberty in another country, since he owes his pre-eminence to the success of it in his own. If France triumphs, the ill-fated proclamation will be a millstone, which would sink any other character, and will force a struggle even on his.^^

In comparison with such words as these, Jefferson's early private comments to Madison and Monroe seem mild. It would almost appear that he was justifying his own official conduct to them against the charge of being a traitor to their political cause and the cause of liberty. Also, the popular support of the French even surpassed his expectations. About six weeks after the issuing of the proclamation he wrote Monroe: "The war between France & England seems to be producing an effect not contemplated. All the old spirit of 1776 is re-

i«Apr. 28, 1793 (Ford, VI, 232).

^■^ May 8 and 27, 1793 (Hunt, V\, 128, 130).

18Madison to TJ, June 10, 1793 (Hunt, VI, i27-i28«.).

kindling." '^ Though rejoicing in this revival of the spirit of liberty, he added: "I wish we may be able to repress the spirits of the people within the limits of a fair neutrality." He took no stock in the criticisms of George Washington. In his opinion, Hamilton, whom Knox supported, was for proclaiming "the most abject principles," Randolph was appallingly indecisive, and, in the councils of the government, every inch of ground had to be fought over desperately to maintain even a "sneaking neutrality." If this should be preserved, the country would be indebted to the President, not his counselors. He wrote Madison in May: "If anything prevents its being a mere English neutrality^ it will be that the penchant of the P. is not that way, and above all, the ardent spirit of our constituents." ^^

There is no indication that he himself did anything to inflame the public mind in this time of reckless and irresponsible journalism, but up to a point he could and did rejoice at expressions of popular opinion which would deter the government from veering to the English side. Also, he observed to Madison that the alignment was much the same as on domestic issues. On the one side were (i) the fashionable circles of Philadelphia, New York, Boston, and Charleston, (2) merchants trading on British capital, and (3) "paper men." All the old Tories, he believed, were included in one of these three groups. On the other side were: (i) merchants trading on their own capital, (2) Irish merchants, (3) tradesmen, mechanics, farmers, and all other descriptions of citizens. These people believed, as he did, that the French were fighting the battle of democracy, whether or not they used that term, and many of them were more passionate partisans than his official responsibilities permitted him to be.

Following the unanimous and virtually inescapable decision on April 19 to issue a proclamation and to receive the new French minister, the executive council met again at the President's house next day to discuss the remaining questions he had submitted.-^ Practically all of these related directly or indirectly to the existing treaties with France, and American obligations under them.-^ The most disturbing obligation, in this time of general war, was the guarantee of French possessions in America, that is, in the West Indies. This guarantee was included in the treaty of alliance that was signed in 1778, when the United States

i» May 5, 1793 (Ford, VI, 238).

20 May 12, 1793 (Ford, VI, 251).

21 TJ's memo, in Ford, I, 226-227.

22 The question of summoning Congress, which was decided adversely by unanimous vote, was an exception. Also, there was a hypothetical question about the reception of the "future regent" of France.

had needed an ally so badly. Some also anticipated difficulty from the provision in the treaty of commerce of the same year whereby the United States agreed to admit to its ports French warships and privateers with their prizes, while denying this privilege to the enemies of France. All of these responsible leaders wanted to avoid any embarrassment to their country which the promises in the treaties might entail. There was a sharp difference of opinion, however, as to the degree and immediacy of danger and as to the policy which should now be pursued.

At the first meeting at Washington's house Jefferson gained the impression that Hamilton regarded the treaties with France as void, and at that time he made notes of his colleague's arguments.^^ He also noted that Knox supported Hamilton's position, "acknowledging at the same time, like a fool that he is, that he knew nothing about it." ^^ He himself had no doubt whatever that the treaties were still valid, and he was supported by Edmund Randolph. At this juncture, however, Hamilton produced a quotation from an authority on the law of nations, Vattel, which seemed pertinent and which could not be countered at the moment since no copy of the latter's treatise was accessible. This led Randolph to agree to look into the matter further. The Attorney General announced that he would give a written opinion, whereupon Jefferson concluded that he would put his own ideas into written form. No opinion was ever offered by Knox, but Hamilton made up for this by writing two, with characteristic loquacity. Thus the private debate between the major antagonists was continued and concluded in writing. Neither Secretary appears to have seen what his colleague wrote. As in the case of the constitutionality of the Bank of the United States, the audience before which the two men debated consisted of George Washington and posterity, but Jefferson had much the better of it on this occasion.

In his written argument Hamilton did not go so far as to claim that the treaties were void, but spoke rather to the effect that they should be regarded as "temporarily and provisionally suspended." ^^ He had backed down a little — perhaps as a result of the discussion in the executive council, perhaps on the advice of his friends. He had discussed matters with Chief Justice John Jay and Senator Rufus King. The latter wrote him: "The change which has happened will not, perhaps, justify us in saying 'the treaties are void' — and whether we may

-^ Thomas, p. 60, cites LC, 14560, saying that TJ on the back of this slip of paper jotted down the principles he himself would use in replying to him.

--»Ford, I, 227.

2i»J.C.H., IV, 363. His two opinions, dated April 1793 and May 2, 1793, are in that edn., IV, 362-390.

contend in favor of their suspension is a point of delicacy, and not quite free from doubt." ^^ In these international matters Jefferson exercised a moderating influence on leading Republicans, while Hamilton's closest political friends were trying to moderate him.