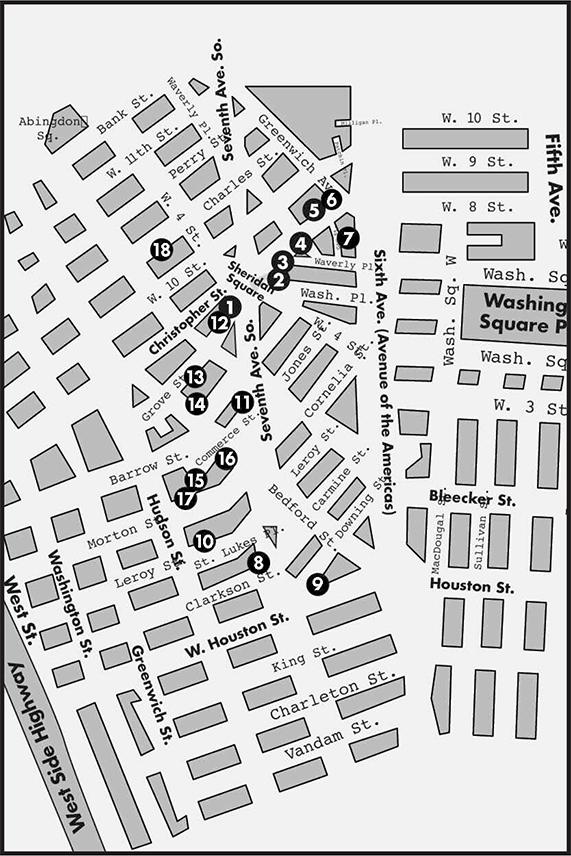

➊ SHERIDAN SQUARE—This square represents the more commercial side of Greenwich Village as evidenced by the large number of tourist traps in the area. This tradition goes back to the late 1910s, when the radicals and bohemians were chased out of Greenwich Village by imitation bohemian restaurants that co-opted their culture. There were theme restaurants like the Toby Club with fake spiders and spiderwebs, the Pirates’ Den where waiters and waitresses got into swordfights, and other clubs imitating prisons, farms and Native American lifestyles.

Such places thrived into the 1920s, as prohibition went into effect. Around that time, there was a tremendous fear of not being able to get a drink for the rest of one’s life; it proved short-lived however, as, according to Police Commissioner Grover Whalen, the number of speakeasies in New York City doubled from fifteen to thirty thousand. The police would even help you start your own liquor club, in return for a percentage of the profits.

At 5 Sheridan Square, in a building that’s been replaced by the current apartment building at 3 Sheridan Square, Barney Gallant ran the Greenwich Village Inn, where he refused to stop serving liquor. When the police tried to arrest one of his waiters for serving liquor, he intervened and had himself arrested, saying he was the architect of the operation. He got a thirty-day sentence in the Tombs, but his arrest was so strongly supported by his fans—and he had many in the Village—that he had a waiting list of visitors, which embarrassed the authorities.

In true “Village Spirit,” when the government tried to release him early he refused to leave because he enjoyed the publicity.

The famous Village Independent Democratic Club was located on the second floor at 224 West Fourth Street. It was a voice of liberalism in the 1950s and 1960s, with the likes of Ed Koch, before he became a corporate puppet, and the late Bella Abzug. This site housed the Greenwich Village Theater, where Eugene O’Neill had his plays produced after he outgrew the Provincetown Playhouse.

Other famous sites around the square include 1 Sheridan Square, the former site of Cafe Society, later Charles Ludlam’s Ridiculous Theatrical Company. At Cafe Society, in 1961, a benefit concert was given by local folksingers to honor one of America’s greatest folksingers—Woody Guthrie.

One hundred-one Seventh Avenue South was a famous lesbian bar called the Duchess, until then-Mayor Ed Koch took its liquor license away in the ’80s by using the anti-discrimination laws against it, effectively closing it down.

Sheridan Square is named for Philip Sheridan, whose statue from the 1930s adorns Christopher Park. Like most of the people honored in this city through statues, he was a man who murdered people, serving as a Civil War general for the North. He’s most famous for his statement that “The only good Indian is a dead Indian.”

➋ 88 GROVE STREET—This was Rose Pastor Stokes’s home in 1918. She was a Socialist, a birth control activist, and one of the founders of the American Communist Party, who deserves more fame than she has received.

She was arrested here for voting, and arraigned at the Jefferson Market Courthouse on Sixth Avenue. She was first arrested for writing a letter to a Kansas newspaper opposing U.S. entry into WWI and was out on $10,000 bail, so when she voted she was technically a convicted felon under the Espionage Act, which makes one ineligible to vote (New York women won the right to vote in 1918 thanks to a 1917 citywide referendum and strong Socialist Party support through mayoral candidate Morris Hillquit’s campaign). Eventually, the ridiculous charges were dropped. (For more on Rose Pastor Stokes, see the Lower East Side I Tour.)

➌ 92 GROVE STREET—This was the site where African Americans were given refuge during the Draft Riots of July 1863. During the heart of the Civil War, working-class men rioted for four days, protesting the national draft. The city government was almost overthrown, barricades a mile long went up on the west side, draft offices were destroyed, and troops on their way to fight confederate troops were diverted to New York City. Sheridan Square was the scene of some of the riots.

The working class fought for two divergent reasons:

1) Resentment over the fact that the rich could buy their way out of the draft for $300 and 2) Racism, which drove them to blame African Americans for the war, and so direct violence toward them.

It is estimated that at least fifty thousand people rioted; a small percent of the African-American population of Manhattan moved out after being terrorized. The only major hospital to give African Americans refuge was the Jews Hospital, on West Twenty-eighth Street, which later changed its name to Mt. Sinai Hospital and moved uptown.

➍ NORTHERN DISPENSARY (165 Waverly Place)—This landmark went up in 1831, serving the medical needs of the poor. A $3 annual donation allowed a donor to send one of his servants for free. After 1960, it became a dental clinic. Folksinger Harry Chapin used it as a child. In 1986, George Whitmore, a patient at the clinic, disclosed that he had AIDS and the clinic refused to treat him. He sued through the Human Rights Commission and won a $46,000 judgment, which caused the clinic to go bankrupt. It’s been empty ever since.

The Northern Dispensary—once an inexpensive medical, then dental clinic. PHOTO BY PETER JOSEPH

On the next block, at the corner of Waverly Place and Tenth Street, there was a horrible gay-bashing incident in 1993; two men holding hands were attacked by three men with golf clubs, fracturing the skull of one of the victims. Appallingly low bail was set after the arrest of the attackers, and a very lenient plea bargain was withdrawn after the case was publicized by the community.

Though we think of New York City, especially Greenwich Village, as a place of tolerance, there are many incidents of violence on gays and lesbians, particularly on weekends.

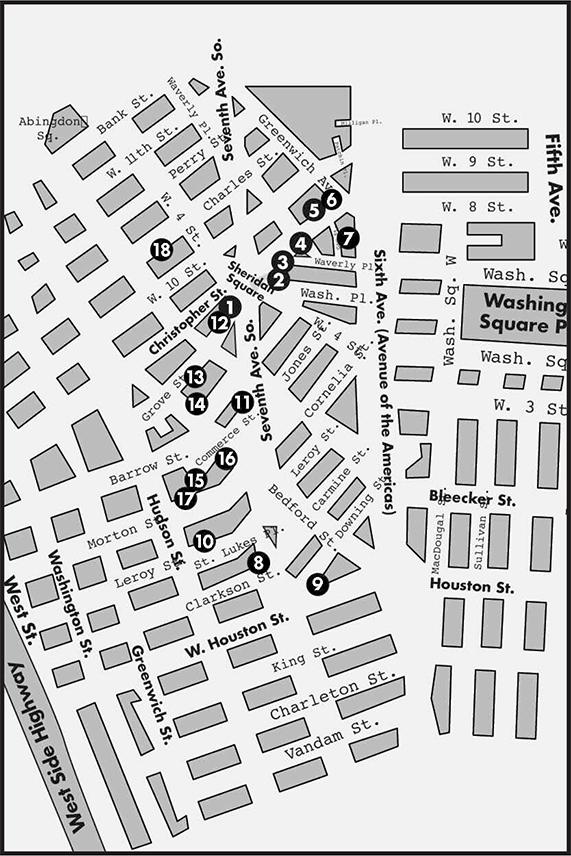

➎ OSCAR WILDE MEMORIAL BOOKSHOP (15 Christopher Street)—This was the oldest storefront gay and lesbian bookstore in the world until it closed in 2009. It was started by gay-rights activist Craig Rodwell in 1967 on Mercer Street. Craig was very active politically after the Stonewall Riots up the block and he bravely maintained the bookstore despite death threats and broken windows. There was a very moving memorial for him at the Gay and Lesbian Center after his death in 1993. Though the rent was below-market-value at $3,000 per month, the store ultimately just couldn’t make it financially despite a slew of owners who tried after Craig’s death. It was named for Irish playwright Oscar Wilde who was jailed for being gay; at his trial he talked about homosexuality as “the love that dare not speak its name.”

➏ FLOYD DELL’S APARTMENT (11 Christopher Street)—On this site, before the present building went up, was a narrow, wooden house that Floyd Dell moved into with his anti-war activist wife, Berta Marie Gage, in 1919. Mr. Dell came from the Chicago literary renaissance and became an editor of The Masses and The Liberator, as well as a director, playwright, and actor with the nearby Provincetown Playhouse. A big part of the 1910s and 1920s village bohemian scene, he would be tried for espionage for his anti-war stance and almost marry poet Edna St. Vincent Millay. He wrote a poem about the old wooden house he lived in here and named his first child “Christopher” in 1922 after the street. The house would be knocked down in 1925 and village residents will know this address as a parking lot for many years until the current building was erected. Though his reputation in the village was for having a lot of short-term affairs, Mr. Dell would ultimately be married to Ms. Gage for 50 years until he died in 1969.

The famous Oscar Wilde Memorial Bookshop on Christopher Street. PHOTO BY PETER JOSEPH

➐ LAW PRACTICE OF THE LATE WILLIAM KUNSTLER AND EX-PARTNER RON KUBY (13 Gay Street)—This house is the site made famous through all of the work these two radical attorneys did over the years. The practice continues, though at a different address after the death of Bill in 1995, when Kuby had a dispute with his widow, Margaret Ratner.

Gay Street is not named for the large gay population living here but for an old Dutch family. This beautiful winding street was also an African-American neighborhood in the 1840s, where many servants working in the area lived. Prior to the Civil War one-quarter of New York City’s African-American population lived on Bleecker, Thompson, Sullivan, and MacDougal Streets.

➑ CARMINE RECREATION CENTER (Corner of Clarkson and Varick Streets)—This public center was erected in 1908 and holds two of the fifty-six city pools open to the public, either for free or at a very low cost. More importantly, it sits on the site of the Clarkson Street Men’s Association, founded in 1830.

In July 1863, shortly after midnight during the first day of the Draft Riots, an African-American man was dragged from the club and lynched. The racist murderers danced a jig under the body.

➒ DOWNING STREET—This is one of the few streets in New York City originally named for an African American. The Downing family was prominent in eighteenth-and early nineteenth-century New York. They owned restaurants throughout Manhattan, one of which served as a stop on the underground railroad for escaped slaves (see the Wall Street Tour).

George Downing was a founding member of the African Free Schools in 1787, which gave a free education to African Americans as slavery was being outlawed in New York State. There were more than a dozen of these schools in lower Manhattan, and they served over five thousand people, including one thousand children. They were originally run by the Manumission Society, eventually merging with the public school system.

➓ 6 ST. LUKES PLACE—This address in a row of fifteen three-story rowhouses went up in the 1850s and was where Jimmy Walker grew up and later lived during his reign as mayor of New York City (one and three-quarter terms in the late 1920s and early 1930s). Mr. Walker’s mayoralty foreshadowed the modern politician, forever untarnished in scandal after scandal.

He did very little work, and was notorious for being loved by the press and taking constant vacations. He used to brag that he never read a newspaper or answered a constituent’s letter. His good looks, dancing, and songwriting abilities made him a symbol of the Roaring Twenties. He was finally forced to resign in 1932, and was divorced in 1941 by the mistress he had married. The house was sold for nonpayment of taxes.

The block is one of the most beautiful in the Village and the rowhouses contain much history. Number Ten served as the exterior of Bill Cosby’s home in the famous 1980s sitcom The Cosby Show; I’m sure the network didn’t realize they shot next door to Max Eastman’s old residence, which was raided by the police in 1920 (Number Eleven—see Greenwich Village III Tour), and again in 1965, when Timothy Leary and Dick Alpert used to live there. Number Sixteen was where Communist Party supporter Theodore Dreiser wrote An American Tragedy and Number Twelve housed Sherwood Anderson, some of whose stories from Winesburg, Ohio were first published in The Masses (see Greenwich Village III).

Weather Underground member Kathy Boudin grew up in the top two floors of number Twelve and a Half. Because her father, Leonard, was a radical attorney, the F.B.I. would harass members of the household, rifle through draws when no one was home, intercept mail and reveal Leonard’s affairs to his wife, Jean. Kathy attended nearby Elizabeth Irwin High School (40 Charlton Street) in 1959 and 1960 with Alabaman Angela Davis. Coincidentally, both would be reunited on the F.B.I.’s Most Wanted List in 1970. The nearby Fourteen St. Lukes Place was sold by actor Robert DeNiro in 2012 for $9.5 million.

Across the street, where the softball field now stands, was the Trinity Parish Cemetery in which nineteenth-century writer Edgar Allen Poe would wander.

The large wall separating the softball field from the outdoor pool displays a vast Keith Haring mural. Haring started as a graffiti artist and soon was painting murals for just about every political benefit of the late 1980s, including Nelson Mandela’s birthday celebration in England. He died in 1990 but his work continues to be exhibited all over the world.

⓫ 9 COMMERCE STREET (at Seventh Avenue South)—If this building looks as if someone literally cut a piece off, it’s because they did. In the 1910s, it was decided to extend the Seventh Avenue subway line below Fourteenth Street to Houston Street. It was also decided, by fiat, that since the subway was to be extended, so too was Seventh Avenue to create what is now Seventh Avenue South. All the buildings in the way were to be knocked down.

The row of houses on Commerce Street begins at number nine because numbers one, three, five and seven were where Seventh Avenue South now plows through. This major construction project, from 1911 to 1917, cleared 194 buildings, and destroyed many of the old winding streets. Village radicals of the bohemian era credit this construction with the death of the bohemian era, since the Village was made to look more like the standard ‘avenued’ neighborhoods, allowing car culture to invade, making the area easily accessible to tourists.

You can see the weird triangular formations created by the construction of Seventh Avenue South, many of which became gas stations and auto supply shops. The small shops that filled up these empty triangles became known as “taxpayers,” because their rent to the landlord of the square block would pay off the real estate taxes on the property.

⓬ MARIE’S CRISIS CAFE (59 Grove Street)—This restaurant and piano bar commemorates the site where the eventually spurned American revolutionary, Thomas Paine, died in 1809. The current building went up in 1839 and is named for Mr. Paine’s Crisis Papers, which began with the famous line “These are the times that try men’s souls.” Though famous throughout the world, Mr. Paine grew less popular for his opposition to organized religion. He had a nasty exchange of letters with George Washington when he was jailed in France for his politics in 1793, and the Father of our Country refused to help free him.

Plaque in front of Marie’s Crisis Cafe on Grove Street, commemorating the fact that Tom Paine died there.

PHOTO BY PETER JOSEPH

⓭ EMMA GOLDMAN’S LAST RESIDENCE IN THE UNITED STATES (36 Grove Street)—Emma Goldman lived here in 1919, before she was deported to the Soviet Union via Finland from Ellis Island. Her comrade and fellow deportee, Alexander Berkman, organized the sailors on the boat, the SS Buford, that was deporting them. They offered to turn around and take him back, but Berkman turned down their offer because he wanted to work for the new Bolshevik Regime in the Soviet Union.

Emma and Alexander set up the Museum of the Revolution in the Soviet Union, but eventually turned against the repressive policies of the Bolsheviks and left the country a couple of years later. Down the block, at 45 Grove Street, is the last manor house left in the Village. It was the residence of famous gay poet Hart Crane, and served as the house of Eugene O’Neill (played by Jack Nicholson) in the movie Reds.

⓮ CHUMLEY’S (86 Bedford Street)—This well-known unmarked restaurant is famous for being a speakeasy during Prohibition. Unfortunately Chumley’s had a major wall collapse in 2007 and has been closed for over seven years, but is expected to be open shortly. It’s little-known, however, for its more radical past. Owner Lee Chumley published the local Industrial Workers of the World’s newspaper here, and held secret meetings in the 1920s. The Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) was one of the leading radical movements of the 1910s, made famous for its songwriting, organizing, and fighting free speech fights on street corners. Its members were deported and killed during various actions on the east and west coasts.

The building itself has many entrances, including an alleged underground tunnel that leads one block away. Police raids during the Prohibition Era for illegal liquor produced no arrests, but once Lee Chumley was arrested in a political raid, for the crime of having an illegal pen knife. More importantly, his typewriter was confiscated when the police couldn’t charge him with anything more serious than possessing the knife.

⓯ CHERRY LANE THEATER (38 Commerce Street)—This building was originally a brewery when it went up in 1836, but in the 1920s it served as the home of the New Playwrights Theater, featuring the work of Michael Gold, John Dos Passos, and John Howard Lawson, who became famous for being fired as a screenwriter by the movie studios in the 1930s for supporting Upton Sinclair’s socialist California gubernatorial campaign. He also served a year in jail as a member of the “Hollywood Ten” during the 1950s McCarthy Era (see Greenwich Village I Tour).

In 1924, Edna St. Vincent Millay, noted Village playwright, poet, and actress, moved the Provincetown Playhouse here because she felt the productions were getting too commercial. In 1951, the theater served as the first permanent home of the anarchist “Living Theatre,” led by Judith Malina and Julian Beck. They were arrested all over the world for their political and revolutionary productions, including The Brig in the early.

The bend in Commerce Street, just past the theater, follows the curve of Dutch Governor Wouter Van Twiller’s farm in the 1630s. He was famous for taking over land with his gubernatorial privileges; he also had a tobacco farm in what is now the northwest part of Washington Square Park.

⓰ 77 BEDFORD STREET—This building goes back to 1799 and is considered the oldest house in the Village, though it’s had two major alterations. The first owner, Harmon Hendricks, had the first copper rolling plant in the American colonies; he and Paul Revere cornered the market in Colonial America, providing almost all the copper broilers used to make rum. I always felt that Paul Revere’s famous ride should have carried the cry “The British are coming; The British are coming and they’re going to take my copper monopoly away!” This would provide a more accurate description of what the American Revolution was fought over.

Next door is 75 1/2 Bedford Street, known as the narrowest house in the Village. It was built originally as a carriage entrance for the bigger house next door and at nine and onehalf by thirty-five feet is now a desired residence in “Always a Housing Shortage and Kept That Way by the Landlords” New York City. Edna St. Vincent Millay lived here for a year in the 1920s while married to Max Eastman’s old roommate, Eugen Bossevain. Archie Leach, better known later as Cary Grant, also lived here with his male lover, but they had to get a third roommate to make the $15 per month rent.

The building sold for $270,000 in 1993 and has rented for as much as $6,000 per month.

⓱ ALLEGED ROSENBERG ESPIONAGE APARTMENT (65 Morton Street)—Apartment 6I was alleged by the FBI to be a “spy den,” used by Julius and Ethel Rosenberg in the 1940s (when the Soviet Union and United States were allies). On June 19, 1953, the height of the cold war, the Rosenbergs were executed in Sing-Sing prison for stealing the secret of the atomic bomb, though it was not quite a secret at the time.

Across the street is Sixty-six Morton Street, a uniquelooking 1852 building that has been used in various movies. In 2015 it sold for $17 million.

⓲ 74 CHARLES STREET—The fourth-floor walk-up in this building was home to Communist Party member and one of America’s most famous folksingers, Woody Guthrie, in the early 1940s. Woody Guthrie paid $27 per month in rent for what was then a dusty and dingy apartment as he waited for the love of his life, Marjorie Mazia, to divorce her husband and move in with him.

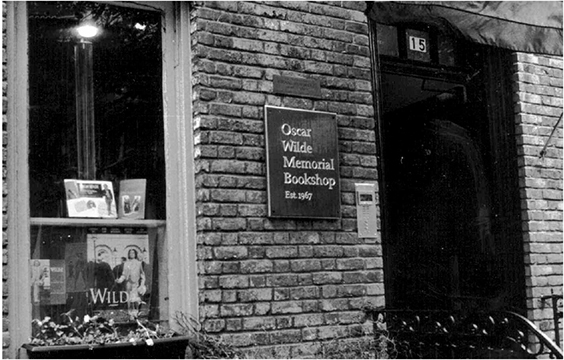

Guthrie spent a lot of time in Greenwich Village. He set up Almanac House, a folksinging commune, on Greenwich Avenue and Tenth Street with Pete Seeger. He drank at the White Horse Tavern on Hudson Street and Julius’ on Tenth Street and Waverly Place. He played his guitar in Washington Square Park with Rambling Jack Elliot in the 1950s, and was widely idolized (and copied) by everyone from Bob Dylan to Phil Ochs. His most famous song is This Land is Your Land, a tribute to the average American in which the most radical verse about private property is usually dropped.

Julius’—still standing at Tenth and Waverly. Woody Guthrie drank here. PHOTO BY PETER JOSEPH

Woody died in 1967, as the folksinging movement he helped popularize was in revival, living long enough, however, to see his son Arlo record Alice’s Restaurant Massacre.

Down the block from Julius’ Bar at 190 Waverly Place is folksinger Dave Van Ronk’s apartment building. In 1961 a young folksinger by the name of Bob Dylan used to hang out there, and then copied Van Ronk’s act as well.

I would end this tour closer to the river on Charles and West Streets where the Pathfinder Mural was displayed from 1989 to 1996. This 5,950 square-foot mural of radicals took two-and-ahalf years to complete and featured the work of eighty artists from twenty countries. Featured radicals included Maurice Bishop, Karl Marx, Leon Trotsky, and Nelson Mandela; it was unfortunately taken down due to deterioration.

The building’s mural side was on the northeast corner of Charles and West Streets with a 14 Charles Lane address. It housed the Socialist Workers Party Pathfinder Press offices but unfortunately has been replaced by a few all-glass luxury apartment building monstrosities.

However, you can walk south two blocks to Christopher Street, make a right turn and walk to the Hudson River to take a rest (and see a beautiful view) at Pier 45. On your way there, note the building at the northeast corner of Christopher and West Streets, which for years was a gay bar but is now closed. It was here in 1979 that hundreds of angry members of the gay community protested the shooting of William Friedkin’s movie “Cruising” with Al Pacino for its terrible portrayal of gays. Protesters blew whistles and made threats against the film’s production at many sites in Manhattan during its eight-week shoot. The protests were sparked by Arthur Bell’s column in the Village Voice, in which he feared that the movie would inspire more violence, and possibly more deaths, in the gay community. Thousands also marched against the movie in a large protest in the East Village.