➊ASTOR PLACE—This open square is filled with history: 13 Astor Place was the United Auto Workers (UAW), District 65 building until the local went bankrupt and was replaced by apartments on the market for between $300,000 and $1,000,000. The building originally went up in 1890, and was used for events by progressive organizations when the union was there, including the Committee in Solidarity with the People of El Salvador, which held marvelous dances.

It now features a Starbucks Coffee on its main floor, which has been visited in protest by the anti-gentrifying Reverend Billy Talen. The newsstand in front of Starbucks and next to the subway station, in the pre-internet era, used to be the first in the city to get the new issue of the Village Voice on Tuesday nights and lines of people looking for apartments would stretch for blocks. The Village Voice used to be represented by District 65 of the UAW.

Astor Place is named for John Jacob Astor, one of New York City’s most famous robber barons. When he died in 1848, he was the richest man in the world, and his family later owned many slum tenements on the Lower East Side.

Some clever artists altered the street signs a few years ago to make ‘Astor Place’ read ‘Peltier Place,’ after imprisoned American Indian Movement (AIM) activist Leonard Peltier. It was an irony wrapped in a word play, since the Astors first made their money by ripping off the Native Americans in the fur trade.

The giant black cube in the center of the square is a sculpture by Tony Rosenthal named “The Alamo.” It went up in 1967 and weighs three thousand pounds. It can be spun by two or more people but watch out for the skateboarders whizzing by.

The highlight of the square is the Cooper Union Building (41 Cooper Square, see photo on page 77), completed in 1854 and five years later housing the college of the same name. Founded by a benevolent capitalist—not a term I use often—Peter Cooper, the school was set up as free education for the working class, inspired by the Polytechnic Institute of France.

Peter Cooper knew there was no such thing as a self-made millionaire, hence he always gave back to the community by, for example, establishing the People’s Institute, which gave progressive lectures to area residents. The building itself includes steel railroad track as girders, and was a major innovator in using steel in the development of the skyscraper, which we all take for granted today.

The circular shaft on the roof was made by Peter Cooper in anticipation of the invention of the elevator, not certain at the time if it would be circular or square. In 1975, the building was renovated with the exterior nineteenth-century walls retained for aesthetic reasons, but no longer structurally necessary.

The Great Hall in the basement has always been open to speakers of all political views, and some of the famous speakers over the years have included Frederick Douglass, Samuel Gompers, Peter Kropotkin, Norman Thomas, Susan B. Anthony, Abraham Lincoln, Amiri Baraka, Max Eastman, Margaret Sanger, Allen Ginsberg, Victoria Woodhull, and Daniel DeLeon. In 1883, there was a commemoration of Karl Marx’s death, and four years later a protest against the impending Haymarket executions in Chicago. In the early 1990s, ACT-UP held their weekly, five hundred-person meetings here and, despite the large crowds when the late, great AIDS activist Bob Rafsky spoke, you could hear a pin drop.

One of the most famous actions in the Great Hall was the horsewhipping Emma Goldman gave her former mentor, German anarchist Johann Most, after he denounced Alexander Berkman, Emma’s lover, for his attempted assassination of Henry Clay Frick. Frick was the chief operating officer of the Carnegie Steel Works, whose vicious lock-out of the workers in Homestead, Pennsylvania resulted in the deaths of seven strikers after a twelve-hour battle with the union-busting Pinkerton detectives.

➋COLONNADE ROW (428-434 Lafayette Street)—This was a row of nine mansions, but only four of the original remain; Wannamaker’s Department Store built its warehouse here, knocking down five of the buildings (the Wannamaker’s name can still be glimpsed on the back of the building, south of the row). These 1833 buildings were where the richest people in the world lived, including John Jacob Astor, Cornelius Vanderbilt, and the Schermerhorn family. Lafayette Street used to stop at Great Jones Street, ensuring that the rich wouldn’t see the people who produced their wealth. Like many expensive buildings in Manhattan, the stone was quarried by prisoners.

Across the street is the Public Theater (425 Lafayette Street), founded by the late Joseph Papp (see Central Park Tour). It was the first major public library and later the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society (see the plaque on front of building and the fading acronym—HIAS—on the north wall). Though it appears to be one building, it is actually three buildings joined together, built in intervals between 1853 and 1881.

➌THE WAR RESISTER’S LEAGUE BUILDING (339 Lafayette Street)—Known as the “Peace Pentagon,” this building was owned by the War Resister’s League from 1969 to 1978 (bought for just $80,000) before it sold it to the A. J. Muste Institute. In 2015 the building was sold by the A. J. Muste Institute for $20.75 million to real estate magnate Aby Rosen. The progressive political groups have since moved to 168 Canal Street farther downtown (www.ajmuste.org). They moved here because their old office at 5 Beekman Place, near City Hall, was raided by the government, provoking the landlord to ask them to leave. More than seventy years old, the WRL organized the first peace demonstration against the Vietnam War, and ran an underground railroad to Canada at the same time. Its most famous members have included Albert Einstein, A. J. Muste, and David McReynolds. It rents space to other progressive groups, such as the Libertarian Book Club, Paper Tiger TV, and the Nicaragua Network.

Colonnade Row, formerly homes to the filthy rich. PHOTO BY BRUCE KAYTON

In the 1970s, this building housed the Free Space Alternate U, a radical school that featured, among other things, radical walking tours led by Bob Palmer and Scott Lewis.

Gazing across Houston Street you are looking at Soho (South of Houston Street). It has become a gentrified strip of cafes and art galleries, with late night clubs and large retail stores. The real estate industry’s designation of the area in which you stand as Noho (North of Houston Street), has not exactly caught on.

If you would like to do a little extra walking, you can make a left turn on Houston Street and walk four blocks to the northeast corner of Houston Street and the Bowery. This is where the very first community garden in New York City was created in 1973 by Liz Christy and the Green Guerrillas. They started a mass movement by local residents all over New York City to clean up garbage-filled lots and turn them into sites of beauty. Of course before the Europeans got here, all of North America was one big “community garden.” You can see the hours of operation (and great before and after pictures of the garden) at www.LizChristyGarden.us.

➍BEETHOVEN HALL (210 East Fifth Street)—Everyone from Emma Goldman, Johann Most and Margaret Sanger spoke in this 1860 building. Leon Trotsky spoke here twice in 1917, denouncing World War I, and there was a memorial for John Reed here in the 1920’s. Many unions held meetings here, especially in the garment industry, as well as women fighting for the right to vote. In 2012 the third-floor apartment was offered for sale for $25 million but there were no takers.

➎THE MODERN SCHOOL (6 St. Mark’s Place)—This building housed the Francisco Ferrer Center of the anarchist Modern School, which featured Emma Goldman, Alexander Berkman, and Upton Sinclair on its board of directors. It later moved to Harlem, and then to Stelton, New Jersey, where it closed in 1953.

Inspired by the execution by firing squad of Francisco Ferrer by the Spanish government in 1909, it was set up to implement his teaching beliefs in a modern, progressive education. He hated government and organized religion, emphasizing equality, brotherhood, and cooperation. More than 120 schools were set up in Spain during his lifetime, before his execution on phony charges of inspiring a general strike in Spain.

In 1912, members of the Modern School took in the children of strikers during the Industrial Workers of the World’s famous Lawrence, Massachusetts strike (see Webster Hall site below). In 1915, it became a Jewish bathhouse, then a gay bathhouse before being shut down in 1985 due to the AIDS crisis. The Modern School still holds reunions and more information can be found at http://friendsofthemodernschool.org.

➏VICTORIA WOODHULL (75 East Tenth Street, northeast corner of Fourth Avenue and Tenth Street, original building no longer there)—Ms. Woodhull was a strong feminist, the first female stockbroker in New York, a spiritualist, a con artist, and the owner of the first newspaper (Woodhull and Claflin’s Weekly) in the U.S. to publish “The Communist Manifesto.” Known as a free-love advocate, she would expose the church officials condemning her lifestyle by pointing out the affairs they themselves were having while married. Ms. Woodhull ran for president five times before women had the vote and gave speeches to packed houses all over the country. Born in 1838, she lived in a building on this site in 1876. Ms. Woodhull set up a dissident section of Karl Marx’s First International at 100 Prince Street over 140 years ago, probably the last time rents were affordable in Soho. She also spoke at Cooper Union, having to wear a disguise as she approached the stage so she could get her speech in before being arrested. Renewed interest in her fascinating life has resulted in a surge of biographies of her since the 1990s.

➐WEBSTER HALL (119 East Eleventh Street)—Built in 1895, this now prominent night club has a long radical history. In 1912, then–Socialist Party member Margaret Sanger led 119 children of the Lawrence, Massachusetts “Bread and Roses” strikers in a march from the train station to have a meal here before being placed with supporters. Though their parents worked in the garment industry, the children wore tattered clothing as they voraciously ate their first decent meal in weeks.

The labor history of the building continued with the 1914 founding convention of the Amalgamated Clothing Workers of America (recently merged with the ILGWU to form UNITE!), led by Sidney Hillman as a move away from the more conservative United Garment Workers of America. The Amalgamated grew to more than ninety thousand members, and Sidney Hillman became an advisor to President Franklin Delano Roosevelt.

In the 1910s, The Masses held raucous costume balls here, some featuring nude revelers, as fundraisers for the always financially-pressed magazine. Other highlights at Webster Hall include various Emma Goldman speeches, and the meeting place of the New York Sacco-Vanzetti Defense Committee. In the 1940s, there were hootenannies given by the group People’s Artists, with Pete Seeger and Woody Guthrie occasionally dropping by.

➑SITE OF 208 EAST TWELFTH STREET (now an NYU dormitory)—This was the site of famous anarchist Carlo Tresca’s newspaper, Il Martello, in the 1920s. Carlo fled to this country from Italy in 1904, where he constantly faced libel charges as he published revealing truths about promiscuous priests who preached abstention. He was involved with the Industrial Workers of the World, dated “Rebel Girl” Elizabeth Gurley Flynn, fought against Italian fascists here in America, and supported the Spanish Anarchists in the 1930s. His newspaper was shut down in 1923 because of a Margaret Sanger ad for birth control; he served six months in jail for this “crime.”

An outspoken opponent of the Soviet Union, the mafia, and capitalism, he was gunned down at a nearby street corner in 1943 (see Chelsea–Ladies’ Mile Tour).

➒WOMEN’S TRADE UNION LEAGUE (Corner of Fourth Avenue and Twelfth Street)—After its New York branch was established in 1903, the Women’s Trade Union League (WTUL) regularly set up a stepladder on this corner for organizing speeches directed at the thousands of women leaving the factories at day’s end. The WTUL was active at the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory strike of 1909, and held social picnics in Central Park as part of its mission to get more women into the union movement.

➓WORKER’S LAB THEATER (42 East Twelfth Street)—This radical theater collective was established in 1929 to reach the masses with political street theater. The core members of The Shock Troupe lived in the building, performing full time at Union Square, workers’ picnics, strike sites, and in the subways. In the 1930s, they performed World’s Fair in opposition to Chicago’s World Fair.

The tradition was continued in the early 1990s by the Nicaragua Network’s group Adelante!, which attacked politicians, the Gulf War, and racism at demonstrations, festivals and on the subways. (While doing guerrilla theater in Manhattan, I was amazed to learn how many public sidewalks are in reality privately owned.)

⓫CLARENDON HALL (112-114 East Thirteenth Street)—The Central Labor Union (CLU), founded in 1882, held meetings here and at the Science Hall at 141 E. Eighth Street. The first labor day parade in the United States was planned here and held later in the year at Union Square (see next site).

In 1886, the CLU invited four hundred delegates and 165 organizations here to fight an anti-labor mayoral campaign, nominating progressive Henry George. He finished second with sixty-eight thousand votes to Abram Hewitt, Peter Cooper’s political-hack brother-in-law, but beat out Theodore Roosevelt, the Republican candidate, by eight thousand votes.

In 1900, there was a meeting here to establish The New York Call, the influential socialist newspaper that became the unofficial organ of the Socialist Party (see City Hall Tour). They featured the best coverage of the 1911 Triangle Shirtwaist Fire.

⓬UNION SQUARE—Named for the union of Broadway and Fourth Avenue (not the large number of union headquarters historically in the area), Union Square was completed in 1835 as one of several squares set up in Manhattan. Prior to this, it held squatters and a potter’s field. In the 1840s, the rich bought up the area and lots around the square began selling for ten times their original $500 value.

In 1882, the first official labor day parade in the country took place here with nearly twenty-five thousand workers marching in demand of the eight-hour day, an end to both child labor and the contract system. The organizers, the Central Labor Union, urged workers to sever all ties to the Democratic and Republican Parties, and unite worldwide. Many in the crowd carried signs urging an end to rent, prompting a New York Times editorial declaring the signs, “grotesque in their disregard of the inevitable operation of the laws that regulate the relationship of men with each other.”

This first labor day march is celebrated each year in September, in what has become a lackluster parade of out-of-touch officials; it’s even been called off in some years due to low attendance.

The radical alternative, the May 1st International Worker’s Day celebrations, started in 1886, when thirty thousand people marched at the behest of the American Federation of Labor, which was on the verge of collapse at the time. Three years later, the Socialist International or “Second International,” made it a holiday for radicals, and by 1890 there were hundreds of demonstrations around the world, including thirty thousand people in Union Square. In the 1930s, between one and two hundred thousand marched until the mainstream unions pulled out in the 1940s.

In 1910, the ILGWU organized a rally of five thousand here, during the “Uprising of the Twenty Thousand.” The following year, a funeral procession for the victims of the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire marched from Washington Square to Union Square.

In 1927, on the eve of the execution of anarchists Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti, machine guns were placed on the rooftops of the landmark S. Klein department store (since replaced by the luxury housing of Zeckendorf Towers in the mid-1980s) to intimidate the crowd that formed to protest their impending deaths. Carlo Tresca spoke at the rally.

One of the most famous demonstrations in Union Square was in 1930, when, during the depression, the Communist Party called for nation-wide demonstrations against unemployment. More than thirty-five thousand people turned up, despite Communist Party leader William Z. Foster having been urged by the government to call off the march. Three hundred police officers watched the crowd, and started beating demonstrators who wanted to march to City Hall. More than seven thousand would make the trip, but several Communist Party leaders were jailed for “inciting a riot.” Fifty school children were picked up by truant officers, their parents being issued summonses. One month later, on International Worker’s Day, thirty thousand marched in a peaceful rally, and the entire New York City Police Force of 18,300 was placed on alert.

In 1893, Emma Goldman was arrested for a speech to the unemployed, wherein she urged those without bread to take it. She spent a year in jail at Blackwell’s Island (now Roosevelt Island), learning the nursing trade; she later earned two medical degrees in Europe.

Carlo Tresca spoke on International Worker’s Day in 1914, denouncing those who killed thirty-three workers in the Ludlow, Colorado strike at the Rockefeller-owned Colorado Fuel and Iron Company. “Name the Murderer!” he thundered and the crowd called back “Rockefeller!”

On June 19, 1953, since the police refused to let organizers use Union Square, several thousand crowded Seventeenth Street adjoining the square to protest the impending execution of the Rosenbergs.

Union Square continued its radical tradition with lesbian rallies during Gay Pride Weekend, a march against the Israeli invasion of Lebanon in 1982, and a march in 1989 against the phony elections in El Savador. By this time, however, the old political culture, with people spontaneously talking on soapboxes provoking discussion, was dead.

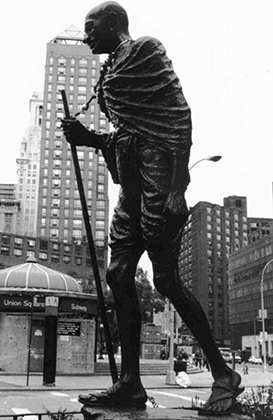

Union Square Park went through a $3.6 million renovation in the mid-1980s which made the park more sterile, making the area more upscale and anti-communal as more chain stores moved in. However, the park does have a statue of Gandhi in its southwest corner (one of the few statues in New York City devoted to someone who hasn’t murdered anyone). I find it ironic, considering his hunger strikes, that he walks toward the Greenmarket fresh-food stalls that are set up several times a week.

On the southeast corner of Union Square East and 15th Street, starting in mid-1880s, used to sit the Union Square Hotel. It is noteworthy for being the hotel union-organizer Mother Jones used to stay in, and speak at events, when she visited New York and as the hotel where Henry George died in 1897. Mr. George was a progressive advocate of the single tax and a mayoral candidate in 1886 for the United Labor Party. He finished second, ahead of future President Theodore Roosevelt.

Around the corner on Sixteenth Street between Union Square West and Fifth Avenue is the Sidney Hillman Family Practice Health Center (16 East Sixteenth Street). Mr. Hillman founded the Amalgamated Clothing Workers of America in 1914 (see Lower East Side I Tour for more information).

If you’re old like me, but still young at heart and you feel like doing more walking, take a stroll east on 14th Street to the subway stop on First Avenue. This is where one of the worst cases of police murder occurred and it was representative of many other cases of illegal police activity. In the early morning hours of September 15, 1983, twenty-five year-old Michael Stewart, a Pratt Institute student, was caught writing graffiti in the subway station. At least ten transit police officers beat him to death, putting him in an immediate coma and he died 13 days later at Bellevue Hospital Center. The outrage over this death in the black community was enormous while I found that most whites would notice the button I was wearing about the case, and ask me who he was. Six of the police officers would be charged and then acquitted after a five-month trial. Dr. Elliott Gross, the New York City Medical Examiner who helped cover up this case and others for the police, would be fired by Mayor Koch in 1987. Artist and graffiti writer Jean-Michel Basquiat’s comment on the murder was “That could have been me.” In 1990 the family of Michael Stewart settled their case against the city for $1.7 million.

Gandhi statue at Union Square. A New York rarity, in that it pays tribute to a nonviolent individual. PHOTO BY PETER JOSEPH