➊306 MALCOLM X BOULEVARD (formerly Lenox Avenue)—This building was the Communist Party headquarters for the Harlem branch in the 1920s and 1930s. Though membership never exceeded one thousand members, more than five times that number turned out for rallies. The African-American Communist Party leadership came from the Caribbean and included Cyril Briggs, former founder of the African Blood Brotherhood for African Liberation and Redemption, and Richard Moore of Barbados, who spoke on many Harlem street corners in this era. The Communist Party in Harlem funded trips to the Soviet Union by African Americans and a news service that sent articles to African American newspapers all over the country.

The Communist Party spoke on street corners and organized rallies without applying for permits. They attracted thousands on issues like the Scottsboro Boys case, where nine African Americans were sentenced to death within two weeks on false charges of raping two white women. This era also saw intense Black-Jewish cooperation; the lawyer representing the Scottsboro Boys, Samuel Liebowitz, was singled out by the prosecutor as a Jew, which perhaps contributed to the loss of the initial case, before it was successfully appealed before the Supreme Court.

African Americans and whites worked together to defend apartments where families were being evicted, and put their bodies on the line over issues important to the Harlem community, such as rent gouging.

The Communist Party organized Councils of the Unemployed and tenants’ organizations. In 1937, novelist Richard Wright, author of Native Son, headed the Harlem bureau of the Communist Party newspaper and wrote in detail about the Communist Party in his less well-known novels.

In 1948, union organizer A. Philip Randolph spoke on what was then Lenox Avenue and 125th Street to urge African Americans to oppose the peacetime draft because of racial discrimination in the Armed Forces. President Truman eventually signed an anti-discrimination executive order, and the campaign was called off. Randolph was expecting to be arrested for making this speech, but was not.

In the 1930s, a young, unknown Communist Party member named Julius Rosenberg worked in a drugstore part time, while attending City University, on then-Lenox Avenue near 125th Street. A middle-aged African-American man was hit by a bus outside, and Julius took him into the drugstore while waiting for an ambulance. Though Harlem Hospital was eleven blocks away, it took an hour for the ambulance to arrive, and the man died right on the floor. As he mopped up the blood, Julius was in shock over how poor city services were in Harlem; he never forgot the incident.

Those wishing to go a little bit out of the way should mark 20 East 125th Street as one of anarchist Emma Goldman’s residences in Harlem at the turn of the century, from which she published Mother Earth.

➋THE BLACK PANTHERS FOR SELF-DEFENSE HEADQUARTERS (2026 Adam Clayton Powell, Jr., Boulevard, formerly Seventh Avenue; the northern store front)—The second Black Panther headquarters in New York City opened here in 1969, and featured Dhoruba Bin-Wahad (then Richard Moore), currently out of jail after a long sentence on a trumpedup charge, and Afeni Shakur, more popularly known as the late rap star Tupac Shakur’s mother (she was pregnant with him during the famous “Panther 21” trial).

This branch studied Karl Marx’s and Lenin’s theories of revolution, and emphasized practical work in the community; though the Panthers were known erroneously as copkillers in the mainstream media, they helped children with their homework, established free breakfast programs, and organized tenants.

The Panthers were one of the best hopes for organizing in the African-American community in the United States, but their early success, with twenty-four chapters around the country, led to government repression that included killings, letter-writing campaigns to provoke infighting between east coast and west coast leadership, and arrests on trumped-up charges with large bail requirements.

There was a spirited reunion of the Panthers in 1986 at the Harriet Tubman School on 127th Street, and a “Panther 21” reunion at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture in 1995.

A new generation of Black Panthers has been publishing a newspaper and videotaping the police when they make arrests in New York City (monitoring the police in the Oakland, California, community was how the Black Panthers started in 1966).

The headquarters building became a community center after this branch was closed in the early 1970s.

Down the block at 2034 Adam Clayton Powell, Jr., Boulevard, is the Washington Apartment House, the oldest apartment house in Harlem (completed in 1884).

➌MANNIE L. WILSON TOWERS (corner of 124th Street and St. Nicholas Avenue opposite Hancock Park)— This senior citizens housing facility was Sydenham Hospital (1925–1980), before Mayor Ed Koch shut it down, creating a symbol of the city’s neglect of healthcare in Harlem. When it was in the private sector, it wouldn’t hire African-American doctors until the 1940s, and was on the verge of bankruptcy when it joined the municipal hospital system in 1949.

In the late 1970s, rather than put money into renovating the building and equipment, the government decided to shut it down because of deterioration. In 1977, mayoral candidate Ed Koch promised to keep it open if he won the election, but, like most politicians, he did the opposite of what he said. Herman Badillo, later to become a deputy mayor in the Koch administration, called Mayor Koch “the most repressive mayor in New York history” for changing his position.

In 1980, upon hearing that a community with inadequate healthcare facilities would be losing one of its major hospitals, thousands jammed public hearings, held on Worth Street. During the 1980 presidential campaign, two thousand rallied at President Carter’s re-election headquarters in midtown Manhattan to demand the hospital be kept open.

The Koch administration decided to close it gradually through attrition, rather than closing it at once, risking community outcry. However, on September 15, 1980, hundreds of people stormed the hospital on its final day of operation, and occupied the administrative wing. Many of the occupiers were members of AFSCME Local 420, led by Jim Butler, who continues to organize demonstrations and fight the privatization of New York City hospitals. One of the leaders of the occupation was radio station WBAI producer Erroll Maitland, who twenty years later would be beaten nearly to death by police while reporting on the beating of a woman at Patrick Dorismond’s funeral in Brooklyn. Dorismond had been shot to death by police in Manhattan after police mistakenly thought he was a drug dealer because he was Black.

Picket lines formed, and an effigy of Mayor Koch was hung outside. On the second day of the occupation, thirty protesters remained inside, and police put barricades up around the hospital to divide the protesters outside from those inside. The crowd fought through the barricades, and the police started hitting people with their clubs. Thirty people were injured in a ten-minute mini-riot with Mayor Koch showing his sensitivity to Harlem residents by calling them “punks, thugs, and provocateurs.”

The next day, more than one thousand rallied outside for three hours to support those inside, but after ten days the remaining nine occupiers were peacefully removed by the police. The hospital eventually closed and became the current senior citizen housing facility in 1987. A few days after the occupation ended, Mayor Koch had to cancel an appearance at the dedication of the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture because of his fear of protests.

➍THE AMSTERDAM NEWS (2340 Frederick Douglass Boulevard, formerly Eighth Avenue)—Founded in 1909, this is Harlem’s most famous newspaper. Currently a weekly that sticks very closely to the Democratic Party mainstream, it is filled with press releases and photo opportunities for local politicians and celebrities. A six-week strike in 1968 won forty-six workers a twenty-percent wage increase over three years (does anyone remember wage increases like this?).

Amsterdam News headquarters. From left to right, Adam Clayton Powell, Jr., Frederick Douglass, and Malcolm X. PHOTO BY BRUCE KAYTON

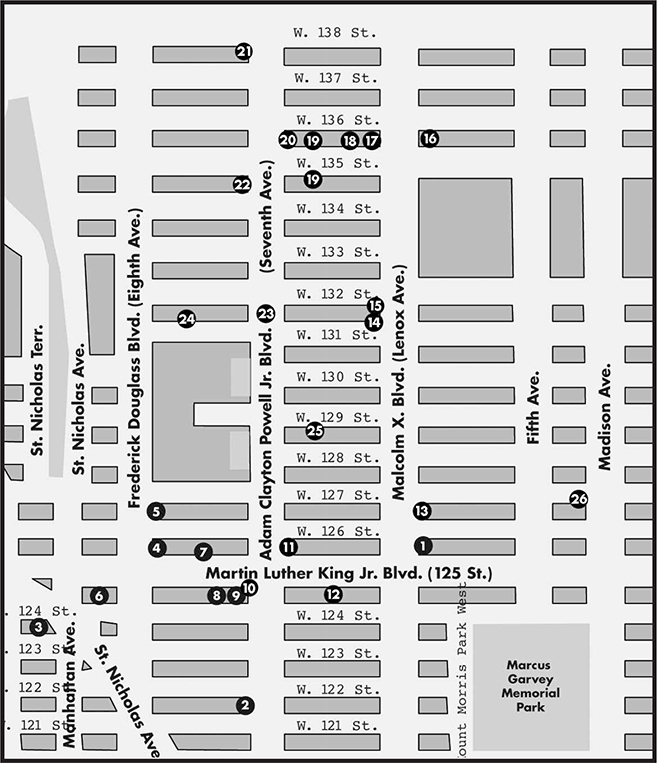

➎UNITY FUNERAL CHAPELS, INC. (2352 Frederick Douglass Boulevard)—The second floor of this building is where Malcolm X’s body lay in state for four days after his assassination on February 21, 1965. Twenty-two thousand people filed past to pay tribute to the thirty-nine-year-old Malcolm as police were stationed all over the area because of bomb threats made against the funeral home.

Malcolm X was one of the greatest speakers in American history, and his uncompromising political stance led to his brutal murder in front of his pregnant wife and four children at the Audubon Ballroom on Broadway and 166th Street. His break with Elijah Muhammad and the Nation of Islam cost him his life, but he was also heavily shadowed by U.S. intel-ligence agencies before he was killed. It is believed he was going to start to work with his long-time rival, Martin Luther King, Jr., the week he got killed—a liaison that was FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover’s biggest nightmare.

Unity Funeral Chapels, where Malcolm X lay in state after his assassination.

PHOTO BY BRUCE KAYTON

Malcolm X is buried in Ferncliff Cemetery in Hartsdale, New York (www.ferncliffcemetery.com). Buses leave from Harlem to the cemetery every year on May 19, the anniversary of his birth.

In 1997, the body of Betty Shabazz, Malcolm’s wife, also lay in state here after her horrible death.

➏SHOPPING MALL—HARLEM USA! (124th-125th streets between St. Nicholas Avenue and Frederick Douglass Boulevard)—This mall opened in 2000, the first shot in a gentrification boom, costing $65 million in tax money to subsidize corporate welfare clients like the Walt Disney Company, HMV records, and Chase Manhattan Bank. Most of these initial corporate welfare clients are gone, having taken the money (to their corporate headquarters) and run. Rents in Harlem are soaring as a result, forcing out Mom-and-Pop shops and, just when things couldn’t get any worse, Bill Clinton moved to Harlem. Mr. Clinton, very symbolically, displaced an Administration for Children’s Services office, but luckily for him he’s within fifty feet of a McDonald’s and a Starbucks Coffee (half owned by basketball player Magic Johnson). A slew of franchises has also come to Harlem, including Red Lobster, Whole Foods, Olive Garden, and Staples.

A convention center for 125th Street, next to the Adam Clayton Powell, Jr., State Office Building, was also proposed in the 1970s. After millions of government dollars were spent on patronage appointments, architects, and lawyers, it was never built.

A different style of economic development program was killed in 1994, when Mayor Rudolph Giuliani kicked hundreds of vendors off 125th Street. Street vendors have been using the streets of New York City as a market since the 1650s, and immigrants have always used peddling as a way to get a foot in the New York City economy. One Hundred-Twenty-fifth Street seems naked and useless without the strong presence of African immigrants selling their wares.

➐THE APOLLO THEATER (253 West 125th Street)—One of Harlem’s most famous landmarks (see photo on page 197), the Apollo Theater still features the weekly Amateur Night Contest. Everyone from Bessie Smith and Duke Ellington to Charlie Parker and Dizzie Gillespie has played the Apollo Theater. Until 1934, it was a whites-only establishment.

In 1971, John Lennon and Yoko Ono played at a benefit concert for the families of the Attica Prison Massacre victims.

Also, in front of this theater, two hundred members of African Americans Against Violence marched in 1995 to protest the Don King–produced homecoming for boxer Mike Tyson, after he got out of jail, where he served time for a rape conviction.

➑BLUMSTEIN’S DEPARTMENT STORE (230–238 West 125th Street)—Blumstein’s was the largest store in Harlem, moving to this building in 1900. Unfortunately the Blumstein’s sign is no longer displayed high above 125th street. It would not hire African Americans for anything but menial jobs. An eight-week boycott campaign in 1934 changed that policy when Blumstein’s hired thirty-five African Americans as saleswomen. (125th Street has been the scene of many “Don’t Shop Where You Can’t Work” campaigns over the years.)

Blumstein’s Department Store was also the site of an assassination attempt on Martin Luther King, Jr. In 1958, during a book signing, a deranged women knifed him. His life was saved at Harlem Hospital, the stab wounds inches from being fatal.

➒THE PEOPLE’S VOICE (208 West 125th Street)—The second floor of this old Woolworth’s Building housed Reverend Adam Clayton Powell, Junior’s The People’s Voice newspaper. Rev. Powell was a major voice for Harlem residents as he arose from his father’s Abyssinian Baptist Church. He was elected to the City Council from Harlem and then to the House of Representatives in Washington, DC (1945–1970). Rev. Powell was extremely active in denouncing racism throughout the city and the country, refusing to go along with the local Democratic Party or Mayor LaGuardia. He was very active on 125th Street in picketing stores that wouldn’t hire Black workers and integrated the local bus company. In 1960 hundreds picketed this building, when it was the Woolworth’s Five and Ten, in solidarity with Congress of Racial Equality activists organizing sit-ins in North Carolina.

Site of the famous Blumstein’s Department Store, a Harlem institution for many years, now closed. PHOTO BY BRUCE KAYTON

➓FORMER HOTEL THERESA (2090 Adam Clayton Powell, Jr., Boulevard)—This hotel is most famous for hosting a then thirty-four-year-old Fidel Castro in 1960 on his first official visit to the United States, a year after overthrowing

U.S. puppet General Battista. (In 1971, it was altered to become an office building.)

Castro came to the United States to speak at the United Nations, but ran into trouble. His plane had to take off immediately after landing because the United States threatened to confiscate it, and no hotels wanted to host him and his delegation. When he threatened to camp out on the lawn surrounding the United Nations, the United States government jumped into action, ordering all hotels in Manhattan to be available to him. He settled on the Shelburne Hotel, but got into a fight with them over how much of a security deposit they required. On a suggestion from Malcolm X, he agreed to stay in Harlem.

He took forty rooms on the ninth floor, and met with Malcolm X the first night. Soviet Premier Khrushchev met Castro at the hotel, and pro- and anti-Castro demonstrators got into fights out front.

A 258-man New York City police guard protected Castro during his stay; only a few short years later, the U.S. government attempted to assassinate him.

In a public relations move, President Eisenhower invited all Latin American delegations except Cuba to a luncheon. To counter the snub, Castro arranged a luncheon at the Hotel Theresa for all of the hotel staff. He spoke for four-and-onehalf hours at the United Nations (one of his shorter speeches).

The building itself went up in 1910. In 1964, at a press conference here, Malcolm X announced the founding of the Organization of Afro-American Unity; it kept offices on the mezzanine level. After Malcolm’s assassination in 1965, crowds gathered in front of the hotel before being dispersed by the police.

⓫ADAM CLAYTON POWELL, JR., STATE OFFICE BUILDING (northeast corner of Adam Clayton Powell, Jr., Boulevard and 125th Street)—This government building was erected in 1973, with protesters demanding that local residents be hired to build it. They weren’t. Other community members demanded that a high school replace the small businesses knocked down to construct it.

On this street corner, from which Malcolm X spoke many times, was Louis Michaux’s National Memorial African Bookstore, whose sign proclaiming there are two billion Black people worldwide served as a backdrop to Malcolm’s speeches, and can still be seen in documentaries of and from that era. In 1906 teenager Elizabeth Gurley Flynn spoke at this street corner regularly as a member of the Harlem Socialist Club. She would go on to fame as an Industrial Workers of the World organizer, co-founder of the American Civil Liberties Union (from which she would later be expelled), and Communist Party member.

The statue of Reverend Adam Clayton Powell, Jr. in front of the building was erected in 2005.

⓬THE STUDIO MUSEUM (144 West 125th Street)—This famous art museum, started in 1968 at a different location on Fifth Avenue, is a welcome relief from the Eurocentric art in most other New York City museums. It sits next to the orange-brick Koch Building, with the word “Koch” still visible on top. Koch’s opened in 1890 to serve the German population in Harlem. They, too, refused to hire African-American workers, or advertise in the African-American press; appropriately, it went out of business in 1930.

⓭SYLVIA’S (Malcolm X Boulevard and 126th Street)—This world-famous restaurant started in 1962, and offers good soul food and great soulful music at its famous Sunday brunches. Many press conferences held in Harlem, featuring the likes of Reverend Al Sharpton or Reverend Jesse Jackson, take place in a tent set up in front of the restaurant. Others who have eaten here include Winnie Mandela and Muhammad Ali.

⓮LIBERATION BOOKS (421 Malcolm X Boulevard)— For forty years Una Mulzac ran this great bookstore (19672007). She had previously owned a bookstore in Guyana but closed it and moved to the U.S. in 1966 after surviving a mail bomb explosion that caused her severe injuries. Another worker in the store was killed by it. She supported Cheddi Jagan and the Socialist People’s Progressive Party but left Guyana after conservatives took over the government. She would die in 2012 at the age of 88.

⓯REVOLUTION BOOKS (437 Malcolm X Blvd., between 131st and 132nd Streets)—This bookstore has bounced around to various sites over the years due to the gentrification of Manhattan. As of 2015 it was moving to this Harlem site from its previous Chelsea location. In case it moves again please check the website at http://revolutionbooksnyc.org/home.html. It is clearly the best radical bookstore in New York City and features a wide variety of reading material on the left. It has sponsored great book readings over the years from, among others, (Too liberal for Mayor Ed Koch) Judge Bruce Wright, Mario Murillo, William Kunstler and Howard Zinn.

⓰HARLEM HOSPITAL (corner of Malcolm X Boulevard and 135th Street)—Healthcare in Harlem started with the establishment of the Harlem Dispensary in 1868, which served three thousand people annually. In 1907, the original Harlem Hospital opened on Malcolm X Boulevard, between 136th and 137th streets. It was at this hospital that Martin Luther King, Jr.’s life was saved in 1958, after being stabbed at Blumstein’s Department Store (see #8 above).

In 1969, the current structure was built, nine years after the money to construct it was first approved. It took so long because of protests over the lily-white construction industry’s failure to hire Puerto Ricans and African Americans. The original Harlem Hospital was also the birthplace of the late Salsa great Tito Puente and the late author James Baldwin.

⓱SCHOMBURG CENTER FOR RESEARCH IN BLACK CULTURE (515 Malcolm X Boulevard at 135th Street)—This new structure, built in 1978, houses one of the best African American history collections in the world. The white building to the west was the original public library branch (built 1905) where all of the greats of the Harlem Renaissance gave readings and did their own reading. Everyone from gay poet Countee Cullen, to the future head of Ghana, Kwame Nkrumah, and Claude McKay spent significant amounts of time here. Langston Hughes walked up its steps on his very first day in Harlem in 1921. Both structures have been combined, so when one is inside it seems like one building.

The library is named for Arturo Schomburg, who was both Black and Puerto Rican; he was active in committees to support Cuban and Puerto Rican independence at the turn of the century. He worked for twenty-three years as a messenger for the Bankers Trust Company, but spent all of his free time collecting writings by Blacks from all over the world.

He established the Negro Society of Historical Research and got articles published in W. E. B. DuBois’ Crisis. He eventually collected more than thirty-three hundred books, and sold them cheaply to the New York Public Library system in 1926 for $10,000, more than doubling the library system’s Black history holdings. Shomburg became the curator of the collection, and died in 1938; he’s buried in Cypress Hills Cemetery in Brooklyn.

The library has excellent archives of A. Philip Randolph’s The Messenger and Marcus Garvey’s Negro World, along with a large collection of videos and photographs. There are two exhibition halls, a great gift shop, and a beautiful tribute to Langston Hughes’s famous poem The Negro Speaks of Rivers in the tiles of the floor outside of the Langston Hughes Auditorium. It has a time line of the lives of Langston Hughes and Arturo Schomburg, which was christened by water from all of the rivers depicted on the floor. Underneath this time line are interred the ashes of Langston Hughes.

This street corner was the site where Marcus Garvey and A. Philip Randolph spoke from a ubiquitous soapbox. They eventually became bitter enemies—the left wingers and the Garveyites fighting over the right to speak on certain street corners.

⓲THE ST. PHILIPS HOUSES (107–145 West 135th Street)—When St. Philips Church purchased this row of houses in 1911 for $640,000, it was the largest real estate transaction by an African American in New York City history. Previously, the houses had only been rented to whites, but the African American real estate agents Nail and Parker quickly pulled down a sign announcing the whites-only policy after the purchase.

St. Philips Episcopal Church (214 West 134th Street) was known as the upper-class African-American church, and they joined the increasing number of African-American churches that sold their buildings in midtown Manhattan at a large profit to buy land in Harlem. St. Philips Church, which sold these houses in 1976, was one of the largest landowners in Harlem. The Communist Party protested against the high rents in 1929, and their front group, the Harlem Unity Tenants League, held meetings at the adjoining library.

When he was known as Harlem’s premier photographer between 1916 and 1930, James Van Der Zee had his studio in what is now numbered 107 West 135th Street.

⓳YMCA (180 West 135th Street, built 1932, and 181 West 135th Street, built 1919)—The older YMCA on the south side of the street is famous for lectures sponsored by A. Philip Randolph’s and Chandler Owen’s The Messenger. In 1921, Langston Hughes stayed here for $7 a week when he first arrived in New York City to attend Columbia University. In 1940, the fifteenth-anniversary convention of founder A. Philip Randolph’s Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters was held here. In 1928, Black Scholar W. E. B. DuBois organized a theater group in the basement called the Krigwa Players to combat the racist stereotypes of African Americans in the theater world, a legacy still with us.

The newer YMCA across the street is where Malcolm X, then known as Malcolm Little, stayed on his first night as a resident in New York City (1942), as opposed to the trips he used to take to Harlem in between his porter duties on the trains.

⓴UNIA OFFICE AND BESSIE DELANEY’S DENTAL PRACTICE (2305 and 2303 Adam Clayton Powell, Jr., Boulevard)—Marcus Garvey, the famous Black Nationalist leader, advocated African-American self-reliance through business ownership. He created the Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA) which set up small businesses all over Harlem. This building (#2305) housed a UNIA office and printing facility.

In 1919, it was home to the offices of A. Philip Randolph’s The Messenger. Number 2303 housed Bessie Delany’s dental practice, which didn’t raise the price for filling a cavity for more than thirty years. The Delany sisters became famous in 1993 with their bestselling book about their previous one hundred years of life, including life in Harlem, and childhoods in North Carolina. Some of Bessie Delany’s clients included Ed Small and James Weldon Johnson.

MARGARET SANGER’S BIRTH CONTROL CLINIC(2352 Adam Clayton Powell, Jr. Blvd., just below 138th Street)—In the 1930s the ever-industrious Ms. Sanger opened a birth control clinic in this building. She got the support of the New York Urban League and local churches in order to allay the fears of Harlemites that it was a research or medical experimentation facility. In the first sixteen months of operation over 3,000 women walked through its doors. It would continue operating until 1945, though under management of the American Birth Control League. Currently, and very appropriately, at 2348 Adam Clayton Powell, Jr. Blvd, is Iris House, a program specifically set up in 2000 to help women who are HIV-Positive or have AIDS. It is named for Iris De La Cruz, an AIDS activist who died at the age of 37 in 1991 and who I knew through both her AIDS and anti-war activism during the first Iraq War. Across Adam Clayton Powell, Jr. Blvd. at 120 West 138 Street (now called Odell Clark Place) is the site of Liberty Hall, which Marcus Garvey bought in 1919 and which had an auditorium seating 6,000 people. In 1920 after the initial evening of the International Convention of the Negro Peoples of the World at Madison Square Garden downtown, all subsequent sessions for the next 30 days were held here. Mr. Garvey led nightly meetings. The original building has been torn down and the current building was built in 1937. Down the block at 132 West 138 Street (Odell Clark Place) is the world-famous Abyssinian Baptist Church, which launched the career of Adam Clayton Powell, Jr. all the way to Congress and which has a large influence on the Harlem community. For more information and more history, go to http://abyssinian.org.)

MARGARET SANGER’S BIRTH CONTROL CLINIC(2352 Adam Clayton Powell, Jr. Blvd., just below 138th Street)—In the 1930s the ever-industrious Ms. Sanger opened a birth control clinic in this building. She got the support of the New York Urban League and local churches in order to allay the fears of Harlemites that it was a research or medical experimentation facility. In the first sixteen months of operation over 3,000 women walked through its doors. It would continue operating until 1945, though under management of the American Birth Control League. Currently, and very appropriately, at 2348 Adam Clayton Powell, Jr. Blvd, is Iris House, a program specifically set up in 2000 to help women who are HIV-Positive or have AIDS. It is named for Iris De La Cruz, an AIDS activist who died at the age of 37 in 1991 and who I knew through both her AIDS and anti-war activism during the first Iraq War. Across Adam Clayton Powell, Jr. Blvd. at 120 West 138 Street (now called Odell Clark Place) is the site of Liberty Hall, which Marcus Garvey bought in 1919 and which had an auditorium seating 6,000 people. In 1920 after the initial evening of the International Convention of the Negro Peoples of the World at Madison Square Garden downtown, all subsequent sessions for the next 30 days were held here. Mr. Garvey led nightly meetings. The original building has been torn down and the current building was built in 1937. Down the block at 132 West 138 Street (Odell Clark Place) is the world-famous Abyssinian Baptist Church, which launched the career of Adam Clayton Powell, Jr. all the way to Congress and which has a large influence on the Harlem community. For more information and more history, go to http://abyssinian.org.)

FORMER SMALL’S PARADISE BUILDING (2294 Adam Clayton Powell, Jr., Boulevard at 135th Street)—This building housed the famous nightclub that featured dancing waiters. It was owned by an African American, Ed Small.

FORMER SMALL’S PARADISE BUILDING (2294 Adam Clayton Powell, Jr., Boulevard at 135th Street)—This building housed the famous nightclub that featured dancing waiters. It was owned by an African American, Ed Small.

Malcolm X worked here as a waiter at the age of seventeen, when he moved to New York City permanently in 1942. He had a reputation in Harlem for being a street hustler by day and the best dancer at nightclubs at night. He was fired because he got arrested giving servicemen the phone number of a prostitute.

He would eventually earn money on his own through various hustles, with the Harlem Narcotics Squad keeping him under close surveillance. After getting into a dispute with a major numbers runner, he was forced to leave New York City for Boston.

Tree of Hope. PHOTO BY BRUCE KAYTON

Malcolm X’s excellent autobiography gives details of his rise from street criminal and ex-con to one of the major American leaders of the twentieth century. As an African-American Harlem resident once said to me: “He talked about white people the way we talked about white people, but only at the dinner table. He did it right in their face!”

THE TREE OF HOPE MEMORIAL (Center traffic island at 131st Street and Adam Clayton Powell, Jr., Boulevard)—This multi-colored structure in the center of the street commemorates the former Tree of Hope, which was near this intersection earlier in the century.

THE TREE OF HOPE MEMORIAL (Center traffic island at 131st Street and Adam Clayton Powell, Jr., Boulevard)—This multi-colored structure in the center of the street commemorates the former Tree of Hope, which was near this intersection earlier in the century.

The tree became known as one with magical powers, capable, through a rub of its trunk, of bringing a job as a singer, musician, actor, or actress. Among those who asked for its charm were Paul Robeson, Bill “Mr. Bojangles” Robinson, and Ethel Waters. Of course, so many performers began hanging out underneath the tree that it became a networking center by itself and eventually entire casts of plays were picked here.

In 1934, with more than four hundred people in attendance, the fifty-foot tree was cut down by the Parks Department in order to widen the avenue. The current marker went up in 1972, but the original stump is now on stage in the Apollo Theater, where it is still rubbed by performers for luck.

Marcus Garvey’s 1917 residence (second house from left).

PHOTO BY BRUCE KAYTON

MARCUS GARVEY’S HOUSE (235 West 131st Street)—One of the most significant African-American leaders of the twentieth century, Marcus Garvey lived in this rowhouse with his wife, Amy, in 1917. He was a major organizer and instilled Black pride in the community, trying to unite Blacks worldwide and creating Black-owned businesses locally. The Black Pride movement of the 1960s owes a debt to Marcus, as do the lyricists of countless reggae songs over the years.

MARCUS GARVEY’S HOUSE (235 West 131st Street)—One of the most significant African-American leaders of the twentieth century, Marcus Garvey lived in this rowhouse with his wife, Amy, in 1917. He was a major organizer and instilled Black pride in the community, trying to unite Blacks worldwide and creating Black-owned businesses locally. The Black Pride movement of the 1960s owes a debt to Marcus, as do the lyricists of countless reggae songs over the years.

Though he is known for his Back-to-Africa Movement, he really set up businesses in America that kept Blacks here. His famous steamship line was designed to make money, not to return Blacks to Africa. He was born in 1887 in Jamaica, and after a bad experience in support of a printer’s strike, he stayed to the right politically most of his life, leading to his condemnation by leaders like A. Philip Randolph and W. E. B. DuBois. He came to America in 1916, spoke on the street corners of Harlem, created the Universal Negro Improvement Association, and published The Negro World, a newspaper with a circulation that neared, at times, one quarter million.

Garvey was a terrible businessman, and his steamship line went bust, costing investors more than $750,000 of their hardearned money. His strong political work, coupled with a lack of business skills, caught up with him as the U.S. government was looking for any excuse to arrest him—he was eventually jailed for mail fraud connected to the steamship lines. He was pardoned by Conservative Republican President Calvin Coolidge in 1927, but on the condition that he leave the country.

The UNIA was in a shambles and Marcus ended up dying poor in England in 1940. However, his legacy, beliefs, slogans, and skills reverberate to this day at countless demonstrations, concerts, and organizing conferences.

FOUNDING CONVENTION OF THE BROTHER-HOOD OF SLEEPING CAR PORTERS (160 West 129th Street)—This is the hall where A. Philip Randolph held the founding convention of the first major African-American union, the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, in 1925. Randolph came to Harlem in 1911, and was inspired by the Industrial Workers of the World, a socialist teacher at City College, and Hubert Harrison, a Socialist Party member.

FOUNDING CONVENTION OF THE BROTHER-HOOD OF SLEEPING CAR PORTERS (160 West 129th Street)—This is the hall where A. Philip Randolph held the founding convention of the first major African-American union, the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, in 1925. Randolph came to Harlem in 1911, and was inspired by the Industrial Workers of the World, a socialist teacher at City College, and Hubert Harrison, a Socialist Party member.

Randolph joined the Socialist Party in 1916, and became a soapbox orator in Harlem on its behalf. In 1917, he started The Messenger, a socialist publication that published many of the stars of the Harlem Renaissance. In 1920, he got 202,000 votes in an unsuccessful attempt to become the first African American elected to a statewide office in New York.

He left the Socialist Party in 1920 in protest of its neglect of African Americans, later founding, before a gathering of five hundred men, the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters.

The Abyssinian Baptist Church and the Amsterdam News supported the union, though many African-American newspapers and churches supported the Pullman Company because of advertising and donation money. The union was not officially recognized until 1937, after a strong push by President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s New Deal legislation.

Randolph continued to be active in the African-American community until his death in 1979. In the 1960s, he threatened to walk out of community meetings if the other clergymen insisted on expelling the young Islamic preacher named Malcolm X. The intersection of 116th Street and St. Nicholas Avenue was designated A. Philip Randolph Square by Mayor Robert Wagner in the 1960s, but currently there is no sign displayed.

Take 124th Street east to Fifth Avenue to view the beautiful Marcus Garvey Park on the way to Langston Hughes’s house on 127th Street. The park dates back to the 1830s and contains a cast-iron firetower from 1856. Back in the old days, before telephones and fireboxes, designated fire watchmen would stand in the tower and look for signs of smoke.

The Black Panthers held classes in the park in the 1960s, and the brownstones surrounding it sell for $2–3 million apiece. The library across the street from the park was erected in 1909, and shows some excellent films on Harlem history and the history of the Civil Rights Movement.

The Langston Hughes house on East 127th Street. PHOTO BY BRUCE KAYTON

LANGSTON HUGHES’ HOUSE (20 East 127th Street)—One of the great writers of the Harlem Renaissance, Langston Hughes lived here from 1947 until his death in 1967. His poetry and short stories are read all over the world, and he takes a place in American literature along with his neighbors Countee Cullen, Carl Van Vechten, Alain Locke, Wallace Thurman, Claude McKay, Zora Neale Hurston, and Ralph Ellison. Hughes grew up poor in Kansas and Ohio, but he came to New York City to go to Columbia University, dropping out for financial reasons after his first year. His first poem to be published in an adult magazine was in W. E. B. DuBois’s The Crisis, at 70 Fifth Avenue in Greenwich Village. His poem The Negro Speaks of Rivers is considered one of the gems of the century.

LANGSTON HUGHES’ HOUSE (20 East 127th Street)—One of the great writers of the Harlem Renaissance, Langston Hughes lived here from 1947 until his death in 1967. His poetry and short stories are read all over the world, and he takes a place in American literature along with his neighbors Countee Cullen, Carl Van Vechten, Alain Locke, Wallace Thurman, Claude McKay, Zora Neale Hurston, and Ralph Ellison. Hughes grew up poor in Kansas and Ohio, but he came to New York City to go to Columbia University, dropping out for financial reasons after his first year. His first poem to be published in an adult magazine was in W. E. B. DuBois’s The Crisis, at 70 Fifth Avenue in Greenwich Village. His poem The Negro Speaks of Rivers is considered one of the gems of the century.

In the 1930s, he spent a year in the Soviet Union, and was amazed at how little discrimination he faced. He wrote poems attacking the rich, and worked with the local John Reed Clubs, set up by the Communist Party. He visited labor leader Tom Mooney in jail in San Francisco. His poem Goodbye Christ said the new Christ is Lenin, Stalin, and the peasants of the Soviet Union. He was called before the House UnAmerican Activities Committee because of the poem, and lost speaking engagements in the South, even though he had become considerably more conservative by the 1950s.

When Hughes died in 1967, he was cremated in Ferncliff Cemetery as a group of mourners held hands and recited The Negro Speaks of Rivers. Martin Luther King, Jr., would quote from Hughes, and there are many famous phrases used today that come from his poems, for example, “A Raisin in the Sun,” “Life for Me Ain’t Been no Crystal Stair,” and so on.

The Hughes’ house has been offered for sale in recent years in the one million-dollar range.