Upstairs, he stretched out on the twin bed in the room that had been his. The bed was far too small to accommodate his six feet three inches with any degree of comfort, but he felt a strong need to be there. He pulled a blanket over himself, but it barely took the edge off the chill. He continued to shiver.

He never felt like he was alone anymore. He felt . . .

Something (someone?) . . .

It was like the intangible heaviness that wakes a person when someone is watching him sleep. Michael couldn’t shake the feeling that something was hovering over him.

Why?

Waiting.

For what?

A clear shot.

He turned onto his side and stared out at the room, hoping to distract himself. Vincent had not changed a thing since Michael had moved out. From the ceiling hung model airplanes they had made together. Michael had never had the heart to take them down, even in high school (opting, instead, to make the room off-limits to anyone who might tease him about it). Over his desk was a bulletin board covered with layers of mementos: Ancient baseball cards. A charcoal sketch of himself and Vincent, done by a stringy-haired blond girl, whose face he could still see, on the boardwalk at Myrtle Beach, in the summer of 1951. Ticket stubs from sporting events and concerts. A picture of himself and Donna Padera: St. Pius Senior Prom, 1962. Poor Donna had been convinced the two of them would become “pre-engaged” that night, whatever the hell that meant. (One of those terms teenage girls used to throw around in those days, just to give their boyfriends heart failure.) Instead, he’d broken the news to her that he had decided to become a priest. She hadn’t taken it well. She’d thrown her corsage on the floor, stomped on it, called her mother to come get her, and never spoken to him again. Even now, more than three decades later, she refused to speak to him when they occasionally ran into each other, despite the fact that she was married to a radiologist and had three kids in private school. So far, he’d resisted the urge to tell her to grow up, but just barely. He could only imagine how she would react if she knew about Tess. Probably hire someone to have him shot.

You should be thinking about Vincent. (And life and death and resurrection.) Why are you thinking about your neurotic high school girlfriend?

There were a number of reasons—good reasons—not to think about Vincent. The most obvious was that it hurt too much to remind himself that Vincent was gone.

Not gone. You know he’s not gone.

All right. But Vincent was somewhere beyond communication, on any level that Michael understood. He couldn’t pick up the phone and call Vincent. He couldn’t turn around and see Vincent standing there, or reach out and touch him. Any contact he had with Vincent from now on would be subject to scrutiny and suspicion; there had been several moments already when he’d thought he felt Vincent around him and immediately told himself he was just making it up out of the need for comfort.

He should be grateful for things he did know. Like the fact that Vincent was safe now, and happy. If Vincent Kinney wasn’t in whatever constituted Heaven, there was no hope for a soul on the planet. For all his stubbornness and his crotchety demeanor, Vincent was, without a doubt, the best person Michael had ever known. Religious without being pious. Moral without being judgmental or self-righteous. Most of all, Michael had admired Vincent’s vehement refusal to claim his own goodness. God only knew (literally) how much money Vincent had given away. He would go out of his way to keep people from finding out. Among other things, he’d built a church and a retreat center with his own money, on the condition that the funds used were identified as gifts from an anonymous benefactor. Vincent had no interest in proving what a saint he was. He did what he did for one reason: to serve God. Vincent had constantly admonished Michael to live a good life with a low profile. “God knows everything you do. If you need to crow about it, you must be doing it for someone else.”

Michael searched for some way out of the pain.

Vincent is out of pain now. And happy.

What if he isn’t? What if he is just gone?

You know he’s not gone.

How?

You know how.

It was true. In the winter of 1954, when Michael was nine, he’d almost died in this room. A couple of weeks before Christmas he’d become very ill, with what the doctors had finally diagnosed as rheumatic fever. That night, he had a fever of 105 and was in and out of consciousness. The doctor and Vincent were with him; he remembered trying to hear what they were saying, but their voices sounded garbled, like a record set on a slow speed. He couldn’t read the looks on their faces, either. Everything was a blur, as if he were underwater. Whatever they were saying, he could tell it wasn’t good. Then Father Donahue had arrived, so Michael knew he was in trouble.

The doctor came over to the bed and checked Michael’s pulse. Michael could open his eyes for seconds at a time, and his focus was a bit clearer. He could see the grave expressions on all their faces. He saw the doctor look over at Vincent. He saw Vincent read the look, then pass it on to Father Donahue. Father Donahue moved to the bed and uncapped a vial of holy oil. Behind him, Michael could see Vincent put his face in his hands. He could see Vincent’s shoulders moving up and down as he wept silently. Then Michael heard Father Donahue speak, in a solemn, hushed tone.

“Per istam sanctam Unctionem, et suam piissimam misericordiam indulgeat tibi Dominus . . .”

Michael didn’t feel anything when Father Donahue touched his forehead. Suddenly, he realized he was above everything, looking down. He could see the top of Father Donahue’s head. He could see Vincent and the doctor, his own body—even his face. He didn’t feel frightened, merely confused. He knew he wasn’t asleep and dreaming. On the contrary, he felt keenly alert. He wondered if he was dead, and if so, why he hadn’t gone anywhere. He was still wondering what he should do when he heard someone call his name. He looked toward the voice. There, in the corner of the room, stood a beautiful woman in a maroon velvet dress with ivory lace around the collar. She was smiling at him, her eyes full of kindness and love. He recognized her from photos he’d seen. She was his mother.

He opened his mouth to speak but found he couldn’t. Instead, she spoke to him.

“It’s all right, sweetheart. You’re going to be fine.” Her voice was gentle and it calmed him immediately. “You’re going to be around for many years,” she said, “because there’s something you have to do.”

Then, as suddenly as she’d appeared, she was gone, fading before his eyes. He wanted to run toward her, to stop her from leaving, but he couldn’t move. He felt himself being pulled back toward the bed, as if by a strong undertow. He had a sensation of dizziness and for a brief moment lost all sense of being anywhere. Then he felt himself open his eyes and look up at Father Donahue, who looked back at him, surprised.

“Grandpa,” he said to Vincent, “I saw my mom.”

Ignoring that, Vincent asked him how he felt. Michael kept trying to tell them what had happened, but they wouldn’t listen. They were preoccupied with the sudden improvement in his condition. Two days later, he was strong enough to get out of bed, and a week later he was back at school.

No matter how hard Michael tried, he couldn’t get a rise out of Vincent. It wasn’t that Vincent didn’t believe him; it was that Vincent acted like Michael was casually reporting something he’d seen on TV.

“Grandpa, I’m serious. I saw my mom!”

“I believe you.”

“But . . . she’s dead.”

“I know.”

“Dead people can’t just come back and talk to you.”

“Apparently they can.”

“What is the thing I’m supposed to do?”

“I don’t know. But you will, when the time comes.”

“But—”

“Michael, what was the one thing Jesus told every person He cured?”

“Not to sin anymore.”

“Besides that?”

“I don’t know.”

“He told them not to mention it to anyone. Which they all promptly ignored, but that’s not the point. Why did He try to keep the miracles quiet?”

“I don’t know.”

“Because He knew that faith based on magic tricks is a shallow faith. He didn’t want them all to get so caught up in the supernatural that they didn’t hear what He was saying to them. All you need to worry about is the message. Stop worrying about how the message came to you.”

The logic made sense, but Michael had never been able to follow the advice. The vision changed his entire personality. Up to that point, he’d been outgoing and gregarious, and loved running around the neighborhood and hanging out with his friends. Afterward, he felt too removed from them to be very interested. He spent a lot of time alone in his room—reading, writing, thinking. Wondering about the other reality . . . this realm that was out there, somewhere just beyond his reach. Trying to keep himself ready for this mysterious thing he was supposed to do.

Michael had been convinced that Danny Ingram was the thing. He still could be. Maybe he’d blown it. Obviously he’d blown it. A tragedy with that much forewarning should have been averted, and he should have been the one to avert it. He asked himself, for the billionth time, if it would have ended differently if he had taken it more seriously before it was too late. He’d never know the answer, but it didn’t really matter. It certainly didn’t matter to the Ingrams.

He finally fell into a ragged sleep.

It was almost dark when he woke. He changed clothes and went downstairs. Barbara was on the phone. He could tell by her forced-patient tone that she was talking to Monsignor Graham, even before she looked over and rolled her eyes.

“Mortuary,” Michael mouthed, and she nodded.

He left a note in the kitchen, telling her to lock up and turn on the alarm when she went home. He had no intention of being back anytime soon.

He drove slowly through the neighborhood, looking at all Vincent’s houses and wondering what to do with himself. He’d lied about the mortuary—he’d already called from the hospital and been told there was no reason for him to go there. Vincent had already picked out and paid for everything. Michael was glad about that. Faith or no faith, rooms full of coffins gave him the creeps.

After weighing the options, he got onto I-85 south and headed downtown. He’d decided that a trip to The Varsity, his favorite fast-food restaurant, would solve both his problems: hunger and the need for a religious experience.

The Varsity, an Atlanta institution, was a glorified hot dog stand on the outskirts of Georgia Tech. Michael wasn’t sure exactly how old it was, but everyone in Atlanta acted as if it predated the Civil War. Tradition and atmosphere were probably larger draws than the actual food, although the latter left nothing to be desired. Michael had loved the place all his life. So had Vincent. It had been “their” place. Vincent used to say that when he died and before he went to Heaven he was going to stop by The Varsity for a fried peach pie. Remembering that, Michael smiled to himself and wondered if he was going to The Varsity just to make sure Vincent wasn’t there.

He’d managed to hit a rare slow time. He made his way up to the mile-long counter. There was no system for standing in line. The next person to get the attention of one of the surly, red-shirted cashiers, by whatever means, was the next person to be served. Right now that posed no great challenge, but after a Georgia Tech game it was an awesome undertaking, to be risked only by the bravest or most foolhardy.

Michael got a couple of hot dogs and fries and sat in his usual place, an upstairs corner that overlooked Spring Street. He felt somewhat guilty about having an appetite, even though he’d had nothing but coffee in the last forty-eight hours. He was also sad to realize the place wasn’t as much of a comfort as he’d thought it would be. He tried to think about all the good times he and Vincent had had here, but he couldn’t get his mind off the fact that they’d never come here together again.

The man at the next table was disregarding the NO SMOKING sign, and the smoke from his cigarette was drifting straight into Michael’s face. Michael waved it away and looked over. He was planning to ask the guy to put the cigarette out or move, but the words stopped in his throat the minute he got a good look. The man was in his midthirties, wearing an obviously expensive black leather jacket that did nothing to offset some intangible smarminess. He was staring at Michael intently, with a look that said he was hoping Michael would say something so he’d have an excuse to vent a lot of pent-up rage. Michael quickly turned his attention back to his food. After a second, he glanced over. The guy was still staring.

Oh, for Pete’s sake. Like I need this.

Michael picked up his tray and moved to the other side of the room. When he glanced up a few minutes later, the guy had turned in his chair so he could continue to stare at Michael.

He has that look.

Did he, or was Michael just imagining it? No. It was a real thing, regardless of its meaning. It showed up in the eyes, as if they were glazed over by a film of something very nearly colorless, like the thinnest possible coating of milk. No sign of life underneath. Soulless eyes.

Michael had seen the look before—in fact, had noticed it often in the course of his travels, even though he didn’t know what it meant. The first time he’d seen it was when Vincent had shown him the Winecoff Fire scrapbook. One of the clippings showed a photo of a man who had been suspected of starting the fire. The alleged arsonist, a career criminal named Roy “Candy Kid” McCullough, was the son of a well-known murderer who was executed in Georgia in 1933. McCullough had the look so blatantly it seemed as if someone had tampered with the photo. (In fact, Michael had half suspected that this was what had happened, until he got out into the world and noticed the look over and over again.) Michael had always been fascinated by McCullough, since he had no one else to blame for his own parents’ deaths. (Certainly more comfortable to blame an ex-con than to blame God.) The rumor was that McCullough had gotten into a heated argument with another participant in a big card game that had been taking place on the third floor. He had stormed out, threatening to get even, and had returned a couple of hours later and set the place on fire. Apparently he had bragged about it to several of his friends, but the authorities had never been able to come up with enough proof to make an arrest. In the meantime, McCullough was convicted of another crime and sentenced to life in prison, and the police let it go at that.

Of the many things he’d read about McCullough, there was one description that had returned, during the Danny Ingram episode, to haunt Michael. It came from a book written by a man who had known McCullough in prison: “Nobody could be better to you than Candy, if he liked you, and nobody was more dangerous than he was if he hated you. . . . Don’t know that I’ll ever understand how Candy could be a warm friend one minute and totally heartless the next, void of any basic human emotions.” Michael could never understand such a thing, either, before he met Danny. Now he understood all too well.

The Danny Ingram affair had started simply enough. In the middle of an ordinary day, Michael had received a phone call from Kevin Ingram, an old St. Pius classmate whom Michael barely remembered. Kevin, who now lived on Long Island, had tracked Michael down through the magazine; he needed advice. He was having a horrible time with his oldest son, and the priest at his parish had been very little help and, in fact, was now becoming annoyed by Kevin’s continued pleas for assistance.

“What kind of problem is your son having?” Michael had asked.

“I think he’s possessed.”

Michael had laughed. Not because he didn’t believe in possession (though he didn’t) but because he thought Kevin was joking. Most parents of fifteen-year-olds were convinced their kids were possessed. When there was no laughter on the other end of the phone, the realization had hit Michael—the guy wasn’t kidding.

Michael had asked why Kevin thought such a thing, but Kevin’s answers were vague: “Weird things happen around him. And he’s not himself anymore. Plus there’s this thing . . . can’t describe it, it’s a feeling . . . the air in the room gets thick and it bears down on you, like gravity has suddenly doubled or something. I know this doesn’t make any sense. You have to come feel it for yourself.”

Michael had agreed to go over to the house and feel it for himself.

The Ingrams lived in a beautiful, solidly upper-middle-class Cape Cod in the suburb of Plandome, on the north shore of Long Island. Kevin was an investment banker and his wife, Maureen, was an attorney in private practice. Their house was decorated in perfectly coordinated fabrics and expensive antiques. A little too heavy on the hunt prints for Michael’s personal taste, but it definitely reflected careful attention to detail and two sizable incomes.

Danny was in his room, where, according to his parents, he’d been all day. He’d been told Michael was coming and apparently was not thrilled about it; he’d been in a morose stupor for hours. Still, the way things had been going, Kevin said, they preferred catatonia to the other options.

“What’s been going on?” Michael asked.

“A lot of weird stuff,” Kevin said. “Things happen . . . lights go on and off . . . the toilet flushes itself . . . one night I was in the den paying bills, and the TV just came on by itself. When I pushed the button, it wouldn’t go off. I finally had to unplug it.”

“Things fall off shelves,” Maureen chimed in. “A couple of times, the gas flame on the stove shot up about a foot high, for no reason.”

“What makes you think Danny’s responsible for all that?”

“It didn’t start happening until a few months ago,” Kevin said.

“About the same time Danny started behaving strangely.”

“And how has he been behaving?”

“He has these bizarre mood swings,” Kevin said. “Before all this, he was a pretty normal kid. A little shy, but nothing to worry about. All of a sudden, he starts flying into these fits of rage, without any warning or provocation.”

Maureen nodded. “He throws things, screams—and he uses the vilest language you can possibly imagine.”

“The rest of the time, he’s just kind of sullen and morose, hardly talks to us anymore,” Kevin said. The pain of it was obvious in his voice. “Every now and then he’s his old self, but not very often, not anymore.” He shook his head, then added: “And there’s that feeling, you know, like I told you. Sometimes it’s a lot stronger than other times, but it’s around all the time.”

“Father, I know my kids,” Maureen said in a mildly defensive tone. “When Danny was little, he would get ear infections, but he didn’t react to the pain, so there was no way to tell. But I always knew. I’d take him to the doctor and tell him Danny had an ear infection, and Danny would be running around like a wild man, and the doctor would stare at me like I was a lunatic . . . until he looked in Danny’s ear and saw that I was right. I’m not saying I’m psychic. But I know when something is wrong, and there is something in Danny that is not Danny.” There were tears in her eyes and she could barely talk. “I don’t care how crazy you think I am, I know I’m right.”

“I didn’t say I thought you were crazy.”

“Well, I know you think it.”

“I promise you, I haven’t had a thought one way or the other. I’m just listening. The minute I think you’re crazy, I’ll tell you, okay?”

Maureen nodded and even smiled a little. Kevin reached across the table and squeezed her hand.

“We’re both pretty wrung out,” he said.

“How long has this been going on?” Michael asked.

“Six months, more or less.”

“And you haven’t been able to get anyone to do anything?”

Kevin shook his head. “Father Garra came over one night and blessed the house, but Danny started screaming obscenities at him and he got mad and left. I think he writes Danny off as a spoiled, obnoxious rich kid who resents authority.”

“Father Garra grew up in Brooklyn, in a very poor family,” Maureen added. “I think he was done with us the minute he saw the house.”

“Well,” Michael said, smiling, “Kevin probably told you that I grew up a spoiled, obnoxious rich kid. And I still resent authority.”

Maureen and Kevin both laughed, but their eyes were filled with fear.

After talking with them a little longer, Michael met with Danny alone, in Danny’s room, the walls of which were covered with posters of heavy-metal bands and pictures of skeletons and winged demons—drawn, apparently, by Danny. The furniture was draped in clothing, mostly jeans and black T-shirts also sporting heavy-metal logos. Danny was a thin, pale-skinned boy with shoulder-length blond hair and watery blue eyes. He sat on the bed and stared into space, answering Michael’s questions with shrugs and two-word sentences. None of which was a sign of anything other than youth. He did seem to be more depressed than the average teenager. His eyes had a peculiar unstable quality, as if he couldn’t see anything in the room, but saw something else in its place. And the air did seem heavy somehow, although Michael couldn’t be sure if he really felt it, or just felt it because he’d been told he would.

“Who invited you here?” Danny suddenly asked, in a voice surly beyond his years.

“Your parents.”

“And what do you think you’re gonna do?”

“I don’t know yet.”

“Just couldn’t pass up the chance to get into a teenage boy’s bedroom?”

“Wrong number, pal. But points for keeping up with current events.”

“What then? Little girls?”

“Sheep. I grew up in Georgia. Why don’t we talk about you for a while?”

Danny stared at him and said nothing.

“You wanna tell me what’s going on?” No answer. “Your folks say you’ve been having a rough time.” No answer. “Look, I’m arrogant enough to think I might be able to do something for you, but you’re going to have to give me a hint.”

“Leave me alone!” Danny screamed. He picked up the lamp by his bed and hurled it across the room; it crashed against the wall and fell to the floor in a thousand pieces. Michael tried to stay calm. Danny was breathing hard and still trying to stare Michael down.

“You already had my attention,” Michael said calmly. No response. Just a glare that made Michael grateful there wasn’t a second lamp. Whatever was wrong with this kid, it was beyond his area of expertise.

Michael surrendered from the glaring contest, turned, and headed for the door. He was about to open it when he heard Danny speak.

“Father Kinney?”

Michael turned around. What he saw stunned him. Danny had collapsed on the bed; he was sitting slumped over as if exhausted. The murderous glare was gone, replaced by a look of fear and complete helplessness. Danny was barely recognizable as the same kid. He didn’t speak again or look up. For a moment, Michael thought he’d imagined hearing his name called.

“Father Kinney,” Danny whispered. It was a statement, as if Danny were somehow introducing the thought of Michael to his brain. Absorbing it.

“Yes, Danny?”

Danny still didn’t look up.

“Do you really think you can help me?” he asked in a small voice.

Michael couldn’t speak for a moment, he was so shocked by the transformation. The kid on the bed was a portrait of humility.

“I’m going to do my best,” Michael finally said. Danny nodded. He stared at his hands, which were in his lap, trembling. At that moment, Michael swore to himself that no matter what it took, he was going to find a way to help Danny Ingram.

Kevin and Maureen were waiting for him in the kitchen, eager to have their suspicions solidly confirmed. Michael knew he couldn’t do that, but he was not going to be one more priest who wouldn’t take them seriously.

“I don’t know what’s going on,” he said to them, “but there’s obviously something. What I’d like to do, as soon as possible, is get someone in here who knows a lot more about this kind of thing than I do.”

“How long will that take?” Kevin asked, ready for another runaround.

“How’s tomorrow?” Michael had no idea how he was going to pull it off, but the outpouring of gratitude and relief that followed was enough to cement his promise.

He’d called his secretary, Linda, on his way back to the office and told her he needed to find someone who had experience with exorcisms.

“Exorcisms?” she asked, in her usual charmingly patronizing tone. (No one on the staff could pour a cup of coffee without an editorial comment from Linda.)

“I’m not joking and I’m pressed for time.”

“Where are you?”

“Plandome. Long Island. First thing you’d better do is check and see if there’s an official exorcist for the Rockville Centre diocese. I seriously doubt it, but I don’t want to get anyone’s nose out of joint.”

“And if there isn’t?”

“I don’t know, try the Yellow Pages. Figure it out. I’ll be back there in about half an hour.”

“I’ll find someone by the time you get here.”

Linda was true to her word, and when Michael got back to his office there was a list of names and phone numbers waiting. Michael looked at the local names and, flying by instinct, called one Father Robert Curso, a parish priest in the South Bronx. According to Linda’s note, he worked at a soup kitchen on 124th Street during the week; there was a number, Michael could probably reach him there. It took a little effort to get in touch with him, since the person who answered the phone at the mission spoke no recognizable language. (Michael tried three and gave up.) He finally got through to Father Curso (“Call me Bob”), who had a brusque smoker’s voice and sounded like a former drill sergeant. Michael explained who he was and why he was calling, then started a brief summary of the case. Halfway through Michael’s spiel, Bob cut him off.

“Has he shown any signs of abnormal strength?”

“Not that I know of.”

“Spoken any foreign language he’s never studied? Exhibited telepathic ability or aversion to religious symbols?”

“They didn’t mention anything like that. Just these minor disturbances and fits of temper.”

“So what makes you think he’s possessed?”

“I didn’t say I thought it,” Michael said, losing patience. “They think it. Look, if you’re not interested, just say so and I’ll call someone else, but somebody has got to do something, because whatever is wrong with this kid, these people are going through hell and no one is doing a damned thing to help them!”

There was silence on the other end of the phone for a moment, then Bob asked, “How old are you?”

“What the hell does that have to do with anything?”

“Nothing, really. I’m just surprised.”

“At what?”

“You got a lot of spunk for a Jesuit.”

“What is that supposed to mean?” Michael asked, though he knew exactly what it meant. Curso, like most parish priests, thought of himself as in the trenches and therefore superior to the order priests. To him, a priest who belonged to a religious order was someone who sat in an ivory tower and wasted time writing his latest PhD thesis on some obscure, esoteric, and irrelevant subject. Secular priests resented the Jesuits in particular, because they thought the Jesuits considered themselves better than anyone else. Which, of course, they did. (The truest description Michael had ever read was a quote from Denis Diderot: “You may find every imaginable kind of Jesuit, including an atheist, but you will never find one who is humble.”)

“Give me the address,” Curso said. Michael gave him the address and detailed directions. “What’s that,” he asked, “forty-five minutes on the expressway?”

“About that.”

“Okay. I’ll meet you there.”

“When?” Michael asked.

“In forty-five minutes.”

“Are you kidding? This time of day, it’d take me forty-five minutes to get to the Midtown Tunnel, not counting the forty-five minutes it would take me to get a cab. I was thinking maybe first thing tomorrow morning . . .”

Bob chuckled. “There you go. Now you sound like a Jesuit.”

“I’ll get there as soon as I can,” Michael said, and hung up, already hating Bob Curso and wondering what the hell he’d gotten himself into.

At the house, Kevin and Maureen had their lists of incidents and witnesses spread out on the table, ready for Bob’s perusal. He ignored it all and asked to see Danny, alone. Michael waited with the Ingrams in the kitchen, telling them what he knew about Bob, which wasn’t a lot. Bob hadn’t been in Danny’s room ten minutes when he returned to the kitchen.

“Father, we’ve been writing everything down,” Maureen said, “in case you have any questions.”

“I don’t have any questions,” Bob said.

“Then . . . you think we’re right?” Kevin asked, afraid to hope.

“No,” Bob said. “I know you’re right.”

At that moment, Michael concluded that Father Bob was, in the kindest estimate, some sort of occult-obsessed drama junkie. (But then, it probably wasn’t easy to find a calm, rational person with a strong exorcism-conducting résumé.) Michael didn’t see how Bob could hurt anything, though, and there was still the outside chance that he could help. Kevin and Maureen were so thoroughly convinced Danny was possessed, they’d probably convinced Danny that he was possessed. For all Michael knew, the theatrics of an exorcism might be enough to convince Danny he was cured.

The bureaucrats had given them the runaround Bob had expected, and then some. They put Danny through weeks of psychological tests, physiological tests, interviews, and various other forms of torment. When the bishop finally exhausted every stalling method he could think of, he sent Michael and Bob to the cardinal. They did the whole dog-and-pony show and left more than a hundred pages of test results and documented incidents. The cardinal promised to get back to them as soon as possible and reminded them how busy he was.

Bob, who’d been through it all before, was frustrated but not surprised. Michael was dumbfounded. What on earth could it possibly hurt for him and Bob to dress up and throw around a little holy water? “The guys in the red hats don’t like to be bothered by thoughts of the supernatural,” Bob said. “They’re afraid it’ll make people think they’re not serious politicians.”

Another week went by. Danny’s fits were becoming more violent and lasting longer. It was clear that if he wasn’t already, he would soon be a threat both to himself and to everyone around him. It was also clear Kevin and Maureen weren’t planning on doing anything other than waiting. There was no point in suggesting they move on to another potential remedy.

At the end of the week, Michael called the cardinal. It took two days to get him on the phone, for which he did not apologize or offer an explanation. He did explain that he had sent the reports to an independent psychologist for “further evaluation.” Dr. Brennan was on vacation for a couple of weeks, but he’d look at them as soon as he got back.

Michael had gone ballistic. “We don’t have a couple of weeks! We don’t have a couple of days! Something has got to happen now!”

He might as well have been talking to concrete. The cardinal just kept repeating his refrain, showing no sign of even hearing Michael, much less taking him seriously.

The next morning, Michael got a call from Maureen. The night before, Danny had attacked Kevin with a fireplace tool, leaving a gash in Kevin’s forehead that had taken eleven stitches to close. Danny fled the house. When he returned, in the early hours, he claimed he didn’t remember doing it. He’d been in his room ever since, but Maureen was afraid to even be in the house with him. Michael hung up and called the bishop.

“Michael, I have been as clear as I know how to be. There is a very definite way a thing like this is handled, and it’s being handled. It will proceed at its own pace.”

“Yeah, well my thing’s got its own pace, and it’s not waiting for you! I’m telling you, if we don’t do something right now, something serious is going to happen! Someone is going to end up dead!”

“Then take him to a psychiatrist.”

“He’s been to a hundred shrinks! If there’s one thing that’s obvious, it’s that he doesn’t need another damned shrink!” And if you’d get off your royal ass long enough to go sit in a room with him, you’d know that . . .

“The experts will make that determination. Meanwhile, I’ve heard all I want to hear about it, and I’m sure you have more than enough work at the magazine to keep yourself occupied.”

Late that afternoon, Michael and Bob had a long talk over a pitcher of beer. Bob knew what he was going to do. He was going to proceed without the Church’s authorization. He wanted, and needed, Michael’s help. At that point in his life, other than the occasional dicey article and a bad habit of running his mouth too much, Michael had never been anything but a good soldier. The thought of being involved in an illicit undertaking did not appeal to him. But there was a prospect that was much worse: the way he would feel if he said no and something awful happened. He agreed.

Michael had been naïve enough to assume that “yes” meant “give me the text and I’ll read the responses.” To Bob, it was a license to begin indoctrination procedures.

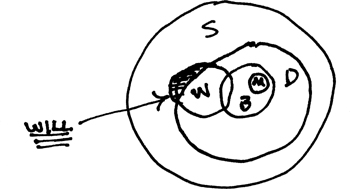

They took a cab to Bob’s church. Bob led Michael to a classroom just off the fellowship hall. He instructed Michael to have a seat in one of the chairs, then Bob went to the green chalkboard up front. He picked up a new piece of chalk and broke it in half.

“Remember Venn diagrams?” he asked.

“I remember hating them,” Michael answered, his mind flashing on connecting circles with shaded areas and letters, and identities like “all attorneys named Sam who drive BMWs.”

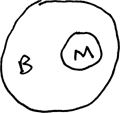

“This isn’t complicated,” Bob said, drawing a small circle on the board. “And it will help you to have a mental image.”

He drew an M inside the circle.

“Mind,” he said, as if that was supposed to make sense to Michael. He drew a larger circle around the M circle. He labeled that circle B.

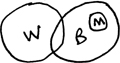

“Body,” Bob said. “Home of the mind.” He drew another circle, intersecting the B circle, and labeled it W.

“Will,” he said.

“Whose theory are you diagramming?” Michael asked.

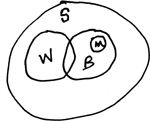

“Mine,” Bob said. He drew a larger circle around the W and B circles and labeled it S.

“Soul,” Michael said, getting the direction, if not the point. Bob nodded.

“Now,” he said, “Father Bob’s Crash Course on Possession Theory.” He smiled; he was enjoying this.

“Is there going to be a quiz?” Michael asked.

“The final exam is tomorrow morning, and this is the only chance you’ve got, so pay attention.”

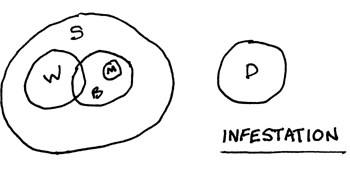

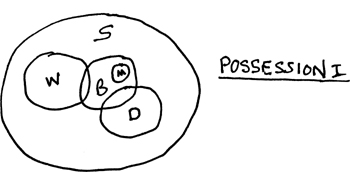

Michael smiled and nodded. Bob’s face became deadly serious. “Most people think there are four stages to possession.” Most people? Most people would have you committed. “I see the actual possession stage as a couple of phases, although it’s all a continuous process,” Bob continued, returning to the board. “The first stage is infestation,” he said as he wrote the word on the board, then began to draw another diagram.

“D for demon. Don’t worry about what he is or how he came to be there; we don’t have the time, and it’s not important right now. During the infestation phase, he hovers here, on the periphery, looking for an entry into the body and therefore the will. There are a lot of physical manifestations at this point. Things the Ingrams described: lights turning on and off, toilets flushing, drawers opening and closing. Also, unidentified sounds: scratching, banging, hissing. The demon is stalking its prey. The point is to make the potential victim disoriented, off balance . . .”

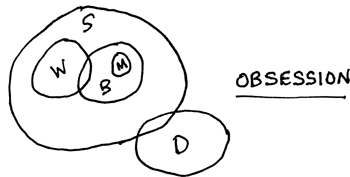

Bob went to the board and drew again. “The next stage is obsession,” he said.

“The victim having been weakened, the demon starts to move in. Invades the soul, weakens the body and the will. Physical manifestations decrease, usually. Most of what is going on at this point is now going on inside. The victim feels agitated, anxious, ill-tempered, has trouble sleeping. People around him will notice a personality change, often a drastic one. The demon’s influence starts to manifest itself in the actions of the victim. Danny’s mood swings, outbursts. Older victims lose their defenses against old vices or pick up new ones—various addictions, mainly, which weaken the consciousness and consequently the will. All of which helps the demon accomplish its goal—to weaken the victim; mind, body, and soul.”

Michael nodded. He couldn’t believe he was sitting here with a straight face, listening to a lecture on the operating patterns of demons. Part of him—in fact, the vast majority of him—had never believed any of this, even when he was begging the bishop to let them proceed with the exorcism. There was another part of Michael, though, to which all this hocus-pocus made some kind of sense, even rang true—as if it were something he remembered from another time, another place.

At the board, Bob was drawing again.

“What I call first-stage possession,” Bob explained. “The victim still retains full consciousness at all times, but he is strongly invaded. He might start to hear voices, maybe even see things.”

“Like what?”

“Bizarre animals, part human, part goat or pig—demons are very partial to cloven hooves, don’t ask me why. Sometimes they’re winged. Sometimes they’re reptilian. Sometimes there’s nothing but a vague black cloud. People who’ve seen it describe it as blacker than any earthly black.”

People who’ve seen it?

Michael’s mind flashed on a commercial he’d seen for some reality-based (yeah, sure) mystery show: two men in overalls, with thick Ozark accents, describing the crashed UFO and dead aliens they’d chanced upon in the woods: “Four were layin’ on the grah-yund.”

Bob was still talking.

“ . . . more sounds. Smells. The victim is assaulted in all his senses, even in his dreams. Dreams become violent and deeply disturbing; they cast a pall over the victim’s waking hours, as well. The point of all this is to exhaust the victim and weaken his will until the demon finds what is known as an ‘entry point.’ ” He stopped for a moment, giving Michael time to take it all in; then he went on. “We’d be here all night,” he said, “if I tried to explain that to you. The simplest way to put it is that the victim is weakened to the extent that he does something—he commits some act, of his own will, that aligns him with the Evil. Evil can never gain an entry without an invitation. It might pound at the door to provoke the invitation, but the victim himself is the only one who can open that door.”

Michael wanted to ask what kind of action the victim had to take—what had Danny done, for instance—but he had a feeling it was another “we’d be here all night” question.

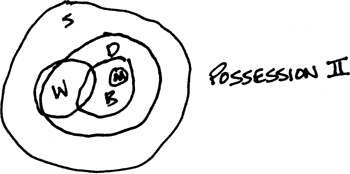

“Then,” Bob said, solemnly, “there’s stage two. That’s where we are now.” He stopped to draw it.

Whether this was a lot of medieval hogwash or not, Michael felt an involuntary shiver as he watched Bob extend the “demon” circle to encompass the circles of body, mind, and most of the will.

“Now the demon has full access to the victim’s body and will. The victim will suffer blackouts, because the demon can move in and go into business for himself. That’s what happened to Danny last night, when he attacked his father.”

“He said he didn’t remember it,” Michael said, putting it together.

“He didn’t remember it,” Bob said. “He could have passed a polygraph saying he didn’t do it, because he didn’t do it.”

Michael sat back in his seat. This was starting to make sense, which didn’t make him feel better.

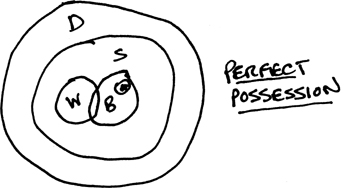

“This little sliver”—Bob tapped a crescent-shaped area of the “will” that remained free of the “demon” circle—“we’ll come back to that.” He began to draw again. “Last diagram,” he said.

“Perfect possession. What we’re trying to save Danny from. The demon, having invaded the victim’s body and will, takes complete control. Once that happens—” He shook his head. “There’s nothing you can do but hope someone locks them up before too many people die. Because that’s all the demon wants—to destroy everything in its path. Death for the sake of death. Evil for the sake of Evil. What is it you Jebbies say? ‘For the greater glory of God?’ Whatever is the exact opposite, that’s what the demon wants. To spit in God’s face. To destroy humanity, God’s creation. To destroy life.”

Bob walked back over to Danny’s diagram.

“Here’s what’s vital,” he said. He pointed to the “free” sliver of “will.” He shaded it in with the chalk, drew an arrow to it, wrote will on the board, and underlined it three times.

Bob tapped the shaded crescent with his chalk.

“Will,” he said. “Will is the heartbeat of the soul. Through will, we can choose to align our souls with Good or with Evil. Danny’s will is still alive in there, but it’s weak. An exorcism is like a quadruple bypass of the will. We’re the surgeons. We have to get in there and make the will strong enough to fight back. Ultimately, there is nothing we can do but strengthen the will. The choice is Danny’s. Danny, with his own will, must choose to deny Evil and realign himself with Good. The important thing is, it’s through the will that we can save Danny.”

He shook his head, disagreeing with himself. “No. God can save Danny. We’re just there to do a job.”

Bob put the chalk down and dusted off his hands. The room was agonizingly quiet. After a moment, Michael spoke.

“I’m still a long way from believing any of this,” he said.

Bob nodded, apparently unfazed. “You know the thing the recovery groups say, about taking the action and letting the feelings follow? ‘Act as if,’ they say.”

“Yeah . . .” Michael replied hesitantly, not sure how it applied.

“Just promise me you’ll ‘act as if’ you believe it between now and tomorrow morning. By the time you find out you do believe it, it’ll be too late for shoring up.”

“You sound pretty confident that I’m going to find out.”

Bob nodded, with a self-satisfied chuckle. “That’s the easy part,” he said.

Michael let it go. He could tell there was no point in offering an alternative hypothesis.

“We’re going to hear each other’s confessions,” Bob said. “Then I want you to go home.” His tone was different; solemn. “Go home and pray. Say Mass. Do whatever you do—just make sure you’re as strong as you’ve ever been when you walk into that room tomorrow morning. Give yourself enough time to sleep, too. Get as much sleep as you need to feel good. In fact, sleep like a baby.” He smiled, a sad smile. “It’s the last chance you’ll ever have.”

Michael kept a straight face and nodded, “acting as if” he didn’t think Bob was a certified fruitloop. He went home, put himself through the motions of “shoring up” ritual, as promised, and went to sleep. Though he tossed and turned and woke up frequently, he slept more peacefully than he knew. In fact, he slept just as Bob had ordered. Like a baby, he slept unaware of the full extent of lurking danger. Like a baby, he did not suspect any vulnerability in the forces protecting him.