12 At the Uplands

Extract from Records of the Borough of Aldeburgh: The Order Book 1549–1631

I heard that Benjamin Britten dreaded the meetings he had to have with Rupert Godfrey to do with the hiring, if that is the word, of the Parish Church for the Festival concerts as much as Rupert Godfrey dreaded his having to discuss them with him. Until I was sent to Blythburgh in 1956 to negotiate with a beyond-Aldeburgh church the increasing presence at home needed great tact. It was not only the performances but rehearsals, the rearrangement of seating, the introduction of stages and, sometimes, all the requirements of a concert hall being met with. Rupert wrote and spoke, ‘Remember you are in a church.’ Yet the music and those listening to it denied secularity. A forgotten holiness was making itself known. One look at Imogen’s face as she conducted the rehearsal for Ben’s Saint Nicolas cantata, for example.

I was singing in this when, in the midst of the rehearsal, an impressive European bass came into the church and Imogen dropped her baton and ran to him. He was wondering where he was to stay – the Uplands of course! ‘Oh, you are so lucky!’ cried Imo. He had walked from the station with a heavy case. No, of course it wasn’t far – it was just across the road. And out they went together. In a minute or two Imo returned and we began singing again. Perhaps ten minutes passed before there were amazed shouts. The bass had returned, disbelief in his voice. Imogen, all of us, stood transfixed. After a kind of roaring we began to hear what was being said. ‘Never, never have I been so treated! Never, never!’ He had been taken through the hotel and into the garden and been shown ‘a chicken hut’!

He had in fact been shown Aldeburgh’s highest form of accommodation, one of the pretty brick lodges in Connie Winn’s garden. These were craved for by visitors. They were unique. And in the main house itself there was comfort and taste – and food – such as no conventional hotel could ever dream of offering to a visitor. The Uplands was run by Connie Winn who I used to think had escaped from a novel by E. F. Benson. She was the daughter of the late Arthur Winn, the best Aldeburgh historian, whose work I devoured and which was the kind of brilliant putting together of often fragmentary facts, which I adored. He was the kind of lifetime researcher of actuality for which no writer of fiction could cease to be grateful. Connie was his only child. She had inherited the Uplands. It was where George Crabbe had been apprenticed to an apothecary, and where Newson Garrett had put down his Aldeburgh roots.

When Ashley Courtenay stayed there in 1950 – Let’s Halt Awhile in Britain – he found the Uplands

like an exclusive London club. It does not even bear a number on its portal … I found myself in an old-world atmosphere of grace and welcome, warmth and comfort … I stepped through the Regency drawing room into the garden, and, in the shade of a gnarled mulberry tree, talked with Miss Connie Winn in what someone described as ‘the best hotel in England’ … I looked through the Visitors’ Book. It was a Who’s Who of the arts, and of the golfers and the yachting world … I noted the books, the flowers, the modern comforts …

And when I was taken there by Denis and Jane Garrett, we all noted – it was impossible not to – the butler sitting a few feet off doing petit point between courses, and Connie seated at the head of the long table which was anything than a version of an inn’s ‘ordinary’ such as George Herbert described. The Uplands was extraordinary. So was Connie. She painted, of course. Her butler and cook had been with her for ever, of course. Her intention was to cast her spell, especially at dinner. It had something to do with the country-house pleasures of the Edwardians, their essential simplicity and ‘everything of the best’. This meant a certain fadedness.

‘Heavens!’ said Imo, having got the singer into the Wentworth. ‘Now, where were we?’ This may have been the recorded Saint Nicolas, I am not sure. Sometimes an interruption becomes the only memory. Connie Winn ran art classes and my friend Anthony Atkinson told me that his life class was heavily subscribed by elderly gentlemen students. There was a plaque to Newson Garrett, the builder of the Maltings. In a sense all the ‘remarkableness’ of Aldeburgh found a footing in this house, it had been a short-stay on-the-way address for so many.

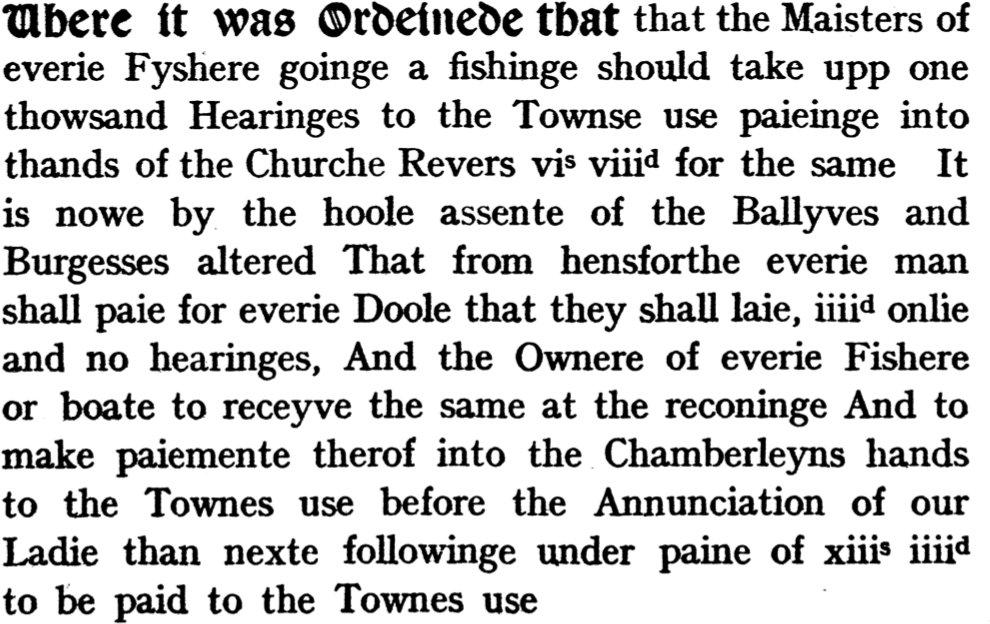

But Connie’s father Arthur Winn would have been uncomfortable with his daughter’s version of the town. In 1925 he had found Aldeburgh’s Order Book for 1549–1631.

‘The writing is good as a whole … but it has been necessary to revive the ink in many places before transcription was possible.’ And so whilst others were deep in the Twenties, playing golf and 78s, he was deep in an Aldeburgh which was not submerged in George Crabbe, an extraordinary Shakespearean task which was more akin to The Tempest than to Suffolk.

We were distracted by Eden and Suez; I was absorbed by Arthur Winn and his ‘briefe note where to find everie ordere’. Thus these Tudor and Jacobean instructions on how to be a true Aldeburgh burgess, having at one’s fingertips

an order for strangers coloringe themselves to be free (black people whitening their bodies), an order for fishing doles, for digging of sand, for stallers of the market, for spirlinge boats for going to the sea upon Christmas daie, for those that are talken of this Towne in inconvenient places, for imprisonment, for carts, for marketfare, for an order for going to the Skarborrowe seas, for making Apprentices free, for gravell, for gowns, so helpe you God and his Sonne Jesus Christ.

I praised her father to Connie. ‘Him and his old books, dear.’

The town had a long tradition of acting as isolated communities often do. Connie’s father Arthur Winn discovered in the Aldeburgh Order Book and elsewhere a great emphasis on municipal, rather than religious, parade and dressing up. Also that it was a stop high on the travelling players’ list:

They travelled in caravans, with their wives, children and servants, living in covered carts, wagons and tents … the journey always made at walking pace … A circuit round England often lasted three years or even longer; the Earl of Leicester’s Servants were here in 1573 … the Queen’s Players seemed to have delighted Aldeburgh audiences more frequently than others. The following are the names of other companies rewarded by the bailiffs: Lord Bath’s Players, Lord Sheffield’s Players, Lord Robert’s Players, Lord Howard’s Players, Her Majesty’s Players.

Whether Aldeburgh had its own Rosencrantz and Guildenstern the Order Book doesn’t say. Maybe climbing the rough road to public worship in their showy gowns was amateur theatre enough.

Imo’s enthusiasm for there being no non-performers in life made her keen to have the local players in The Dumb Wife of Cheapside, a comedy by Ashley Dukes, and for me to describe it. It was all about Alderman Groat who is married to a pretty wife – who is dumb. He calls in the medics – against legal advice. The apothecary–attorney is much against having anything done. It is best to leave well alone. But when the apothecary, the surgeon and the lawyer join forces a miracle has to happen, and Mrs Groat’s tongue is released. She now talks non-stop. Her voice is heard all over Cheapside. Her garrulity drives London mad … Who or what can shut her up – or just give her pause? Dukes has stolen his play from Rabelais but it is a lively theft.

People once had fishy names – Bass, Carpe, Crabbe, Pike, Playce, Sammon, Shrimpe, Spratt, Turbutte, Wale, Whiting. Food included a lot of ‘mackeral fare’. There were many drownings and local men and unknown men washed up by the sea were carried in the same coffin to their graves. Strong winds were not able to blow away the smells which filled the church and the rushes, broom and straw which carpeted it became ‘verie noisome’. Hence the following bill for perfume (only an historian like Arthur Winn would have a nose for such items):

| To Gates for pfume | 4d | ||

| for pfumes and Frankinsence | 1s 2d | ||

| To Mr Oldringe for pfume oyle and Frankinsence for the Church | 1s 6d | ||

| To Mr Oldringe for pfumes at Christide and Easter | 3s 0d | ||

| For rushes for the Towne Hall | 10d |

The most poignant expense at the Parish Church was the ten shillings paid to Robert Fowler in the seventeenth century ‘for looking to the clock and for killing owles’.

Having just been given her father’s book (by Rupert Godfrey) I ached to talk about it to Connie Winn. But somehow she had left Aldeburgh for E. F. Benson’s Rye, and was out of reach.