1. BLACK POWDER, ALCHEMY, AND BOMBARDS

THE EARLIEST WEAPONS WERE DEFINED BY HUMAN STRENGTH AND INGENUITY. THEN CAME THE DISCOVERY OF A HISTORY-CHANGING CHEMICAL REACTION.

A painted silk banner from the 10th century shows Buddha being attacked by demons, one of whom is holding a gunpowder tube.

An Explosive Power

THE EXACT ORIGINS OF GUNPOWDER ARE UNCLEAR. BUT EARLY TAOIST TEXTS REFER TO INCENDIARY POTIONS CREATED BY ALCHEMIST MONKS.

The story of firearms begins with chemistry: the invention of gunpowder.

For millennia men expressed hostility by hurling hard objects at each other and stabbing foes with sharpened sticks. Ancient armies besieged enemy castles by harnessing mechanical ingenuity. They launched waves of flaming arrows, enormous stones, rotting animal carcasses, and even stinking loads of excrement.

But the discovery, possibly in 10th-century China, that combining charcoal, potassium nitrate (or saltpeter), and sulfur could cause explosions and, if properly channeled, send matter flying with deadly effect, changed the course of conflict.

Alchemists Searching for Immortality

The exact timeline of the development of “black powder” is unclear. But Taoist texts from the ninth and 10th centuries include references to the incendiary properties of potions created by alchemist monks. Some sustained burns and there was at least one report of a workshop going up in flames. For the monks, it was a hazard of searching for an elixir yielding immortality. For some of the holy men’s contemporaries, however, the black powder may have suggested a way of limiting mortality, rather than extending it. It is believed that Chinese of the era had the idea to use black powder in rudimentary bombs, grenades, and land mines against invading Mongols. The Mongols, in turn, are thought to have carried knowledge of black powder across Asia, spreading it through the Middle East and on to Europe.

In 1241, for example, advancing Mongol forces used powder- powered weapons to help trounce defenders of the Kingdom of Hungary and lay waste to their villages during the Battle of Mohi. Ideas moved from East to West, and soon intermingled with European innovations. The 13th-century writings of English philosopher and Franciscan monk Roger Bacon contain cryptic references to exploding powder, while medieval alchemists across the continent began to experiment with elements of black powder in their attempts to “transmute” lead to gold.

Part of the fascination with these evolving weapons were their terrifying dramatics. Not only did the arms have the capacity to knock down and kill opponents at great distances, their repeated explosions generated impressive noise, flames, and smoke. The armored knight on a grand steed suddenly had to both carefully watch his back and negotiate threatening new conditions out on the battlefield.

The Birth of the Cannon

By the late 13th century, military inventors realized they could use black powder to fire projectiles from an iron tube closed at one end. The cannon (from the Latin canna, referring to the hollow stem of a reed) was born. The closed end of the weapon came to be known as the breech. Powder and then a projectile were loaded via the open end, or muzzle. A soldier ignited the powder with a torch or smoldering ember through a touchhole in the rear. Rapidly expanded gases from the explosion propelled the ammunition from the barrel—the same basic principle used in firearms to this day.

Illuminated manuscripts of the era show soldiers igniting vase-shaped weapons firing arrow-shaped projectiles. Other early cannon propelled carved stones and iron balls to assault castle walls. En-gland’s King Edward III used a type of cannon called a bombard against the Scots in the 1320s, and there are reports that cannon were used in the Hundred Years’ War.

Exploding Cannon

Primitive artillery did not always operate effectively. The chemical instability of early gunpowder recipes led to unintended explosions. Crude metallurgy meant that cannon frequently burst apart. Even when they worked properly, early muzzle-loaded weapons weren’t terribly accurate, and increasingly sophisticated fortifications limited their impact.

Yet the psychological and physical effects of detonation changed the nature of warfare, allowing armies that deployed cannon in numbers to prevail against entrenched targets. By the 15th century, French and Italian artillery makers were producing transportable wheeled cannon used by such rulers as King Louis XI of France and his successor, Charles VIII, to consolidate power.

Early Look In his treatise on siege weapons, 14th-century English scholar Walter de Milemete included what might be the first illustration of a firearm. The weapon, called a pot-de-feu, was a primitive cannon made of iron.

Battle of Crecy An illuminated manuscript by medieval French author Jean Froissart included this image of the Battle of Crecy (1346), during the Hundred Years’ War. Cannon may have been used in the struggle, but the decisive weapons were the bow, axe, mace, dagger, and sword.

THE MYSTERIOUS FRIAR BACON

In the 19th and early 20th centuries, certain historians identified Roger Bacon (1241–1292) as a major figure in the development of firearms. Some researchers asserted that the Franciscan friar’s writings contain a cryptogram describing the ratio of ingredients needed for gunpowder. This view of Bacon fit with a broader impression that he was an early scientist of mystical bent.

While it’s possible that Bacon saw a demonstration of Chinese firecrackers, modern historians now doubt that he understood the concept of storing and releasing explosive energy via gunpowder. The passages in question probably did not originate with Bacon, and in any event the mixture described has the wrong proportions of ingredients to power a firearm.

FIREARMS ON THE BATTLEFIELD

Mongol warriors are thought to have carried knowledge of black powder from China, through the Middle East, and on to Europe.

800-900 While searching for elixirs for a longer life, Taoist monks discovered explosive black powder.

1241 Europeans encountered black powder, brought by Mongols from China, in a battle against the Mongol Empire.

1260 Muslim soldiers packed early cannon with black powder in their conflict with Mongols at the Battle of Ain Jalut.

1346 British forces fighting the French during the Hundred Years’ War may have used bombards, an early form of artillery, at the Battle of Crecy.

1453 The arsenal used by Ottoman Turks to capture Constantinople included wheeled cannon. The conquest marked the end of the Roman Empire.

1476 During the Battle of Morat, in which the Swiss faced off against Burgundy, both sides wielded hand cannon.

Early Cannon and Artillery

MILITARY DESIGNERS BEGAN TO CREATE CANNON THAT COULD FIRE ARROW-SHAPED ITEMS, CARVED STONES, IRON BALLS, AND MORE.

DARDANELLES GUN

Country: Turkey

Date: 1464

Length: 17ft

Bore: 25in

This 18-ton bronze bombard was constructed in two parts (the rear powder chamber is shown at right), and its projectiles could smash fortress walls a mile away.

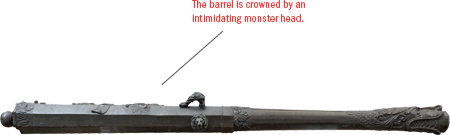

16TH-CENTURY BRONZE GUN

Country: Germany

Date: 1570

Length: 5ft 10in

Bore: 1.6in

This gun was embossed with a warning: “Who tastes my eggs won't find them pleasant.”

15TH-CENTURY BRONZE CANNON

Country: France

Date: 1478

Length: 7ft 3in

Bore: 9.6in

This 1.6-ton bronze cannon, a technological leap over its iron-forged predecessors, likely required ten times its weight in charcoal to melt the bronze.

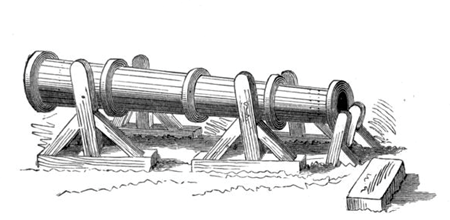

15TH-CENTURY BOMBARDS

Country: Great Britain

Date: circa 1430

Material: wrought iron

In 1434, during the Hundred Years’ War, the British army abandoned these twin bombards on the coast of France.

Enter the Hand Gonne

PORTABLE FIREARMS WERE A BIG STEP FORWARD ON THE BATTLEFIELD, BUT IT OFTEN TOOK TWO SOLDIERS TO FIRE THEM.

IRON HACKBUT

Origin: Netherlands

Date: circa 1500

Barrel Length: 28in

Caliber: .90

Made entirely of iron with a small touchhole, this 12-pound, four-foot hackbut, or "hook gun," was mainly used by foot soldiers.

15TH-CENTURY ARQUEBUS

Origin: Europe

Date: 1470–1500

Barrel Length: 40in

Caliber: 1.2

Columbus conquered the New World with similar weaponry.

As black powder was adopted to fire projectiles, weapon design began to evolve. Metal forgers worked with iron and bronze to create weaponry that varied greatly in caliber, mobility, range of fire, angle of fire, and firepower. Early cannon were loaded at the muzzle and ignited with a smoldering matchcord or a red-hot poker.

Parallel with the spread of cannon technology came the invention of portable muzzle-loaded firearms suitable for use by individual infantrymen.

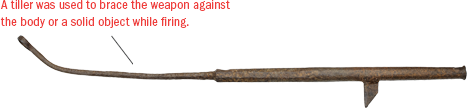

This miniaturization of gunpowder weapons led to the widespread introduction in the 15th century of “hand cannon,” also known as hand gonnes. Soldiers held these crude forerunners of modern firearms under the arm or braced against a shoulder. Some early models, heavy and ungainly, had to be steadied on a stake and required two men to aim and fire. The user ignited the powder by means of a smoldering length of cord, or “slow match,” susceptible in wet weather to becoming soggy and unusable.

By contemporary standards, the one-man 15th-century French hand gonne barely resembled a firearm at all. It consisted of just a small, smoothbore iron barrel one inch or so in diameter attached to a flat wooden stock by means of thick iron bands. Soon, though, hand cannon assumed the rough shape of a modern pistol, with a grip that bent downward from the barrel at roughly a 30-degree angle. Both the Swiss Confederate Army and their opponents, the soldiers of French ruler Charles the Bold, Duke of Burgundy, used such pistols during the Battle of Morat (1476). By the 16th century, craftsmen in Spain and elsewhere were fashioning hand cannon from bronze and decorating them with animal imagery and other flourishes. For those who could afford it, the firearm became a work of art.

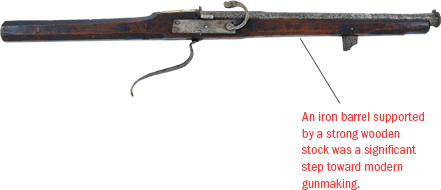

The Force of the Arquebus

The earliest weapon vaguely resembling a modern long gun—a firearm with a wooden stock and extended barrel—was known as the arquebus and appeared in the early 1400s. The weapon was also known as a harquebus, harkbus, or hackbut, from the Dutch haakbus, meaning “hook gun.”

Typically, an arquebus was muzzle-loaded by a soldier who packed it with powder and a lead ball, then ignited the powder by means of a handheld matchcord—an approach that did not solve the difficulty of shooting in damp conditions. It had an iron smoothbore barrel of perhaps 40 inches in length that was connected to a wooden stave (a narrow block) that the soldier would clamp under his armpit to stabilize the weapon as he fired it. (In time, the stave, designed for greater comfort and ease of use, evolved into the familiar wooden shoulder stock.)

Arquebuses achieved impressive force and penetration. Modern-day experiments with replicas have shown that when they worked, the weapons could hurl an iron ball that pierces steel 1.5 millimeters thick. On the downside, they were inaccurate, a problem designers attempted to solve by including a hook near the mouth of the barrel to place over a wall or other stable object.

By the 16th century, gun designers had improved firing systems so that the arquebus and its successor, the musket, were easier to handle and somewhat more reliable.

Just Add Sulfur

It took early experimenters many centuries to perfect recipes for effective gunpowder consisting of sulfur and charcoal, both fuels, and saltpeter, an oxidizer. An 11th-century Chinese text, Wu Ching Tsung Yao (Complete Essentials from the Military Classics), refers to mixtures used in firecrackers, as well as rudimentary flamethrowers and rockets. The formulae, scholars determined, allowed for incendiary effects—the ignition of flame—but not the gas-releasing explosions needed to propel a projectile. The problem? Insufficient saltpeter.

Hand Cannon

THESE WEAPONS WERE CRUDE FORERUNNERS TO MODERN FIREARMS.

HAND CANNON

Origin: Europe

Date: late 15th century

Barrel Length: 7 1/4 in

Bore: .625

This band-reinforced cast iron gun weighed only 1 1/8 pounds.

MEDIEVAL HAND CANNON

Origin: Europe

Date: circa 1350

For ammunition, fighters often packed this hand-forged gun with stones and nails.

BRONZE HAND CANNON

Powder Magic A hot iron rod placed in the touchhole ignited the powder to loudly propel projectiles.

Country: China

Date: 1424

Length: 14 1/16in

Caliber: .59

This hand cannon is on display at New York’s Metropolitan Museum.

FIRE STICK

Origin: Western Europe

Date: circa 1380

Barrel Length: 6in

Caliber: .78

To use the fire stick, also called a Bâton à feu, a soldier inserted a wooden pole into the breech.

METAL HAND GUN

Origin: China and Korea

Date: 17th century

This three-barrel gun was often used as a signaling device, but it may also have been used on the battlefield.

Over time, simple hand cannon evolved into harquebuses— muzzle-loaders with an underside hook that could be used to steady the weapon on a wall or portable support. Some also featured a wooden shoulder stock that functioned as a brace. Echoes of this design element can be seen in the modern gun stock.