2. MATCHLOCKS AND MUSKETS

INNOVATIVE GUNSMITHS INTRODUCED FEATURES THAT MADE IT EASIER FOR A SINGLE SHOOTER TO AIM, FIRE, AND HIT A TARGET.

Englishmen with muskets battle with Hawaiian Islanders in an engraving showing the death of the Royal Navy's Captain James Cook.

Building a Better Firearm

GUNSMITHS IN EUROPE AND ASIA SEARCHED FOR NEW WAYS TO IGNITE BLACK POWDER, TO MAKE WEAPONS EASIER FOR SOLDIERS TO USE, AND TO INCREASE ACCURACY.

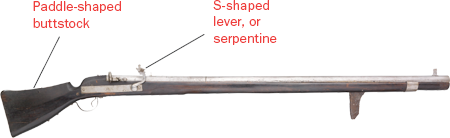

EARLY 16TH-CENTURY MARTIAL MATCHLOCK MUSKET

Country: Spain

Date: circa 1530

Barrel Type: smoothbore

In 1565, Spain used matchlocks to establish St. Augustine, Florida, the first permanent European settlement in what would become the United States. This gun was designed to be used with a forked rest.

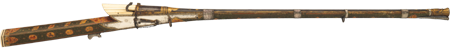

Hi Nawa Jyu

The Japanese only embraced gunpowder weapons after they saw how efficient muskets were on the battlefields in the late 1500s. Eventually they produced highly decorated matchlocks (called hi nawa jyu) that signified power and status.

The proliferation of military and sporting firearms in Europe, Asia, and elsewhere gave rise to a new class of craftsmen whose designs and ambitions drove the advancement of small arms. These gunsmiths searched for more reliable means of igniting powder, more potent formulations of the powder itself, and ways to make guns easier for a single man to use. Ultimately, designers aimed for weapons that allowed for repeated shots without reloading and, of course, they yearned to improve accuracy. The next critical chapter in the story of firearms involves the development of the matchlock firing system.

A Slow Burn

Until about the 16th century, soldiers set off the powder charge for a hand cannon or arquebus by lighting a short length of cord soaked at one end in a chemical, often potassium nitrate (saltpeter), to slow the burning process. The procedure was decidedly awkward: It required the gunman to balance a heavy weapon while bringing the “slow match” into contact with the gun's small touchhole. Then the flame leapt through the opening and lit the powder.

The introduction of the matchlock gun made ignition easier, if not exactly a snap. This new generation of weapons were still muzzle-loaded by means of a slender wooden “ramrod” used to force powder and a ball down through the barrel into the breech. The shooter then placed a match in a device that was attached to the breech. This “matchlock” held the match in an S-shaped lever known as a serpentine. After lighting the match, the shooter depressed the trigger, lowering the match to a pan of finely ground powder known as primer. If all went as planned, the primer ignited, causing an explosion that propelled the ball in the direction of the target.

In due course, designers came up with a more advanced spring-loaded matchlock that moved the serpentine more swiftly and reliably. But the matchlock mechanism didn’t overcome the problems of keeping the match lit in poor weather or preventing the flame from touching the powder prematurely, a common cause of accidental discharge and shooter injury. Another hazard: The light of the smoldering match and ignited powder could give away a soldier’s position to the enemy.

Despite its shortcomings, the matchlock remained popular through the early 1700s, in large part because it was relatively simple to operate and inexpensive to make. Some arquebuses were refitted with matchlocks, but as the technology improved, a sleeker triggered weapon, known as a musket (from the French mosquette) became increasingly common on European battlefields. King Henry VIII of England ordered 1,500 matchlock guns from craftsmen in the Venetian Republic in 1544. Many of these prized weapons were lost, having seen little if any service in Henry’s army, when the monarch’s flagship, the Mary Rose, sank the following year in the Battle of Solent.

A Design Evolution

Matchlock designs varied. Some muskets in the 16th century had mechanisms similar to early crossbows, with longer levers that the user pulled upward instead of triggers that moved from front to rear. After Portuguese forces introduced matchlock muskets to Japan, local gunsmiths began producing a version with a short, curved stock and beautiful brass inlay, known as the hi nawa jyu. Combatants in the English Civil War (1642–1651) used more workmanlike muskets that were lighter and easier to handle. Later matchlock muskets, with their more attractive finishes and formfitting wooden stocks, began to resemble what we would recognize today as a long gun.

POWDER PLAY

Soldiers armed with matchlock muskets carried a supply of gunpowder in a large flask or a bandoleer of smaller containers. The larger style of flask was bell shaped and often constructed of iron and wood with a fabric covering. The soldier tipped out the proper amount of powder by means of a nozzle at the narrow end of the flask. In the bandoleer version, the musketeer filled small flasks with enough powder to fire his gun once and attached them to a beltlike strap that crossed his torso.

A LONG TRANSITION

Between the middle of the 15th century and the dawn of the 20th, warring nations increasingly integrated guns into their arsenals.

1440s Ottoman infantry troops adopted matchlock arms from Hungarians, setting the stage for the weapons to spread through the Turkish empire.

1544 Henry VIII acquired 1,500 matchlock muskets from the Venetians. The British king then lost some of his new arsenal in a shipwreck in 1545.

1550s In a transition from swords and bows, Japanese military leaders began arming soldiers with the hi nawa jyu, a weapon adapted from Portuguese muskets.

1640s During the English Civil War, musketeers, vulnerable to charging cavalry, required protection by infantry.

1900s Illustrating the staying power of older technology, nomad Tibetan forces continued to rely on matchlocks in conflicts with Chinese invaders.

Matchlocks

BOTH THE IGNITION MECHANISM THAT HELD THE SMOLDERING MATCHCORD AND THE GUN ITSELF COULD BE REFERRED TO AS MATCHLOCKS.

MATCHLOCK MUSKET

Country: Austria or Germany

Date: late 17th century

Barrel Length: 47 1/2in

Caliber: .90

The tapering barrel was fit with rear and front sights.

MATCHLOCK MUSKET

Country: Sri Lanka

Date: 1690

Barrel Length: 27 1/2in

Caliber: .90

The butt of this ornately carved handgun could rest against the shoulder or chest.

SNAPPING MATCHLOCK

Country: Italy

Date: circa 1540

Barrel Length: 42in

Caliber: .47

Brescia, where this model was made, remains a gunmaking hub today.

Once a shooter pulled the trigger of a matchlock, an S-shaped lever forced the matchcord into a pan of priming powder. When the powder was lit, it produced a flash to ignite the main charge. Even with the new ignition device, weapons still were muzzle loaded using a ramrod.

Sporting and Hunting Guns Proliferate

FOR ARISTOCRATS AND MERCHANTS, BEAUTIFUL WEAPONS BECAME STATUS SYMBOLS.

JEFFERSON’S MUSKET

Country: Tunisia

Date: 1789

Barrel Length: 84in

Caliber: .69

The Bey of Tunisia gave this musket to President Thomas Jefferson in 1805.

By the mid 16th century, royal, aristocratic, and merchant-class weapon owners were commissioning long guns for nonmilitary sporting purposes. With increasingly elaborate features, these firearms nodded to their owners’ success and social position. Animal-image inlays of bronze, gold, horn, or mother-of-pearl became popular. In Germany and Austria, craftsmen grew skilled not only at ornamentation, but also in advancing the mechanics of the matchlock and its successors, the wheellock and flintlock.

Through the 17th and 18th centuries, most sporting and hunting weapons, like most military guns, remained smoothbore, meaning the interior of the barrel was not “rifled” with spiral rifling grooves, and fired a solid lead ball. For hunting birds, rabbits, and other small game, sportsmen loaded their smoothbore guns with “shot,” a small amount of lead pellets that upon firing would spread into a cloud of pellets called “a pattern” that could bring down fast-moving prey of modest size.

In time, gunsmiths incorporated a technique called rifling, first introduced in the 15th century, which involved boring grooves on the inside of gun barrels. Originally the procedure had been designed to reduce powder residue from building up in the barrel. But 17th and 18th century gunmakers discovered that rifling offered another advantage: Parallel spiral grooves caused the ball, or bullet, to spin in flight, vastly improving accuracy. A fraction of rich European sportsmen paid to have their muskets rifled to improve hunting efficiency, and small, specialized army units also carried limited numbers of rifles. Still, the procedure was difficult and expensive to execute and rifling remained rare until the fabrication advances of the Industrial Revolution.

A SOCIAL MEDIUM

During the Middle Ages, the hunt for food evolved into a social activity, guns included, for the upper classes. Aristocrats adopted a stylized version of hunting as a sport, viewing it an honorable use of their leisure time and a manly form of competition. Women, too, were invited along to shoot, and did so in all their finery.

But the shift to hunting as recreation for the wealthy also created social friction. Where the landed aristocracy claimed exclusive rights to feudal territory, they found themselves at odds with commoners who continued to hunt for subsistence purposes. The legendary outlaw Robin Hood acquired his heroic status, in part, for hunting “the King’s deer.”

Hunting and Sporting Guns

FROM THE 16TH TO 18TH CENTURIES, LONG GUNS SPREAD ACROSS EUROPE.

MATCHLOCK GUN

Country: Germany

Date: 1621

Barrel Length: 48in

Caliber: .567

The narrow Flemish barrel has a large V-shaped backsight and flared muzzle.

SNAPHAUNCE GUN

Country: Scotland

Date: 1614

Barrel Length: 38in

Caliber: .45

The stock and shoulder butt are made of Brazilian wood.

MATCHLOCK GUN

Country: India

Date: 17th century

Barrel Length: 41 3/4in

Caliber: .65

Nearly 10 pounds, this steel-barrel gun is embellished with silver, gold, copper, and ivory.

Regional preferences were reflected in design features as well as style of firing mechanism. In Scotland, the snaphance was popular, while in Italian and German lands, gunmakers favored the wheellock. For large game, some hunters opted for rifles, which were more powerful than smoothbore shotguns and fired a single, large-caliber bullet.