In Poland, the Ju-87 Stuka dive-bomber earned a fearsome reputation within the Polish rank and file. Deadly accurate in its dive, the Stuka crews affixed sirens to their aircraft and they would shriek down out of the sky to deliver their bombs on Polish troop and vehicle convoys. Such attacks helped break the spirit of Poland’s defenders.

I was the first correspondent to reach Guernica, and was immediately pressed into service by some Basque soldiers collecting charred bodies that the flames had passed over. Some of the soldiers were sobbing like children. There were flames and smoke and grit, and the smell of burning human flesh was nauseating. Houses were collapsing into the inferno.

—Noel Monks, London Daily Express, 1937

THE BOMBERS THUNDERED OVERHEAD sometime after lunch on an April day in 1937. Curious Basque citizens turned their faces skyward to see orderly formations of twin-engine aircraft paraded overhead, shepherded along by an equal number of fighters. Curiosity turned to terror when the bombs began to fall. Panic stricken, the men, women, and children of Guernica fled the streets for the sanctuary of cellars and stout-walled buildings.

One of the first fast twin-engine bombers produced by a resurgent Germany in the 1930s was the Junkers Ju-86. Such aircraft helped destroy Guernica during the Luftwaffe’s terror bombing experiment in the Spanish Civil War.

Messerschmitt Bf-109s and Fiat CR-32s swept down on the town to strafe those who attempted to fly the town and gain refuge in the countryside beyond. It was cold-blooded murder, and it lasted for almost four hours. When the German and Italian planes finally turned for home, Guernica burned virtually to the last building. In the ashes lay the corpses of 1,650 civilians.

Wolfram von Richthofen, seen here on the Eastern Front during World War II, conceived and executed the terror raid on Guernica and was quite pleased with the subsequent results.

Following the experiment at Guernica, the beautiful city of Barcelona became the next terror bombing test case. Hundreds more civilians died as Italian aircraft pummeled the city with bombs. These two attacks helped convinced the Luftwaffe’s leadership that Douhet’s theories had merit. They set the stage for Warsaw, Rotterdam, and the London Blitz.

Noel Monks, a daring war correspondent who would later spend time in France with the RAF during the Phony War and beyond, later wrote in his memoir, Eyewitness, “A sight that haunted me for weeks was the charred bodies of several women and children huddled together in what had been the cellar of a house.”

The Germans and their Nationalist Spanish allies denied any involvement in the attack. It was not until 1999 that the German government formerly acknowledged the Luftwaffe’s role and apologized for what took place there that day in 1937.

In the midst of the Spanish Civil War, the Luftwaffe’s leadership had decided to test Guilio Douhet’s nihilistic vision of terror bombing. The people of Guernica did not know it, but they had been selected as the guinea pigs for this doctrinal experiment. Families died, children burned alive as flames consumed their homes, and in a secret report, Condor Legion commander Wolfram von Richthofen declared the attack to be a tremendous success. The will of the survivors in Guernica had been broken.

Adolf Hitler offers a warm greeting to Reichsmarschal Hermann Goering, commander of the new Luftwaffe. The German air force’s performance in Poland and the Battle of France sent Goering’s political influence soaring. Only after the Battle of Britain did his standing erode in his Fuehrer’s eyes.

German troops fight their way into a Polish village during the initial invasion in September 1939. The Poles fought valiantly, but they were overmatched against the more modern Nazi war machine. The Luftwaffe’s tactical air support, combined with its terror bombing of Warsaw, played a key role in the Polish defeat.

German officers in a field headquarters coordinate and set the tempo of the battle flow in Poland. Coordination between the forward units and the Luftwaffe proved to be very difficult, but also of tremendous value in crushing opposition with minimal losses in return.

Polish troops fought fiercely and inflicted heavy losses at times on the German Wehrmacht. But when the Soviets invaded Eastern Poland, the soldiers lost all hope. Crushed on both flanks, the Poles surrendered Warsaw, and the war ended a few days later.

The Stuka’s fixed gear, slow speed, and lack of armament became manifestly obvious as soon as its crews faced a determined and modern air force. Against the Poles, French, Belgians, Dutch, Danes, and Norwegians, however, the Ju-87 served up stark terror to its targets.

The Junkers Ju-88, the fastest twin-engine bomber then in service, saw extensive combat over Poland, France, and the Low Countries. Used both as a level bomber and a dive-bomber, the Ju-88 later found another niche as a night fighter. It became the mainstay of the Luftwaffe’s nocturnal interceptor force along with the Messerschmitt Bf-110.

Two years later, Adolf Hitler’s Wehrmacht invaded Poland, a move that triggered France and Britain to declare war on Germany. For the second time in twenty years, Europe descended into the nightmare of another general war.

Though the Luftwaffe had developed mainly into a close support force, Wolfram von Ricthofen’s Douhetesque experiment at Guernica was taken to heart. From the outset of the fighting, the Luftwaffe conducted terror raids against the Polish capital. Civilians were strafed by passing fighters. Heinkel He-111s and Dornier Do-17s pummeled Warsaw daily with bombs. On September 10, 1939, they flew seventeen raids against the city and caused so much havoc the residents referred to that day as “Bloody Sunday” afterwards. The Germans ignored many choice military targets, such as Polish Army barracks and army facilities around the capital, choosing instead to stick with Douhet’s playbook.

Defended by a hundred thousand desperate and courageous Polish soldiers, Warsaw held out for over a week in the face of overwhelming German forces. As the siege progressed, the Poles even managed to counterattack and push the Wehrmacht back in places. Hitler turned to the Luftwaffe to break the siege. Von Richthofen wanted to burn the capital to the ground, making it fit only as a “customs station” in the future. Terror would bring the Poles to their knees.

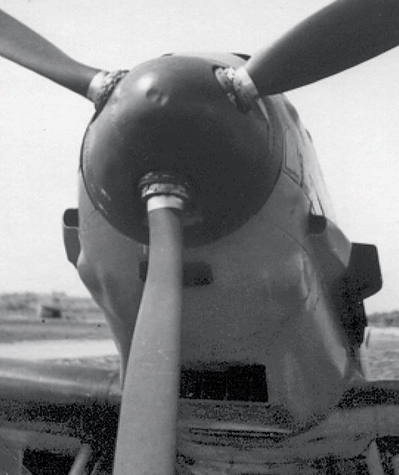

A close-up of a Messerschmitt Bf-109’s nose. The 109 possessed an excellent rate of climb and a slight speed advantage over its most capable adversaries, including the French D.520 and British Spitfire. Its extremely short endurance made it an impractical escort fighter.

Ju-87 Stuka crews study maps in the final minutes before a mission against targets in Norway. Airpower played a vital role in Nazi Germany’s successful campaign in Scandinavia.

The wrecked remains of Polish bombers, seen in the aftermath of the first campaign of World War II.

The German Army, though largely composed of infantry dependent on horse-drawn transport, did possess a thoroughly modern armored force. Used en masse at weak points along enemy defensive lines, the panzers achieved numerous critical breakthroughs during the campaigns of 1939 and 1940. Without the panzer menace, it is quite possible the terror bombing unleashed on Poland and Holland would not have had the effect that it did.

A painting of a German bomber pilot. Thanks to their combat tours in Spain during the Civil War, Luftwaffe air crews were among the most experienced and well-trained in the world in 1940.

German troops react to incoming artillery fire. In the 1939 and 1940 campaigns, the Wehrmacht defeated its opponents through superior organization and better integration of airpower into the land war. Without the Luftwaffe, these early victories would not have been possible.

A formation of Bristol Blenheim RAF bombers. The Blenheim was one of the most numerous twin-engine strike craft in the British arsenal at the start of the war. Early attacks on German naval bases in broad daylight resulted in heavy Blenheim losses and helped convince the RAF high command to switch to night bombing.

To conquer Holland, the Germans used daring tactical operations that gained strategic results. This included the airborne assault on Fort Eben-Emael, a key defensive complex that could have held up the main German invasion force for many days. Instead, fewer than a hundred German paratroopers—including the ones seen here—landed atop the fort and captured it in a surprise coup de main. Such an operation would never have been possible had not the Luftwaffe owned the skies over Holland from the outset of the 1940 campaign.

By concentrating its panzer divisions in the lightly guarded Ardennes sector of the Western Front, the Germans were able to rupture the Allied lines and cut much of the Anglo-French Army off in Belgium. This forced the Allies to withdraw over three hundred thousand men from the continent at Dunkirk. That disaster presaged the complete collapse of France and its surrender after forty days of fighting.

A true multinational effort. American-built, French-flown Hawk 75 fighters escort a formation of RAF Fairey Battle light attack bombers. The Fairey Battle squadrons in France were virtually wiped out in the fighting following the German invasion of the West in May 1940.

German citizens look over the wreckage of two Allied bombers shot down during the 1940 campaign. In the background are the skeletal remains of a Vickers Wellington, the mainstay of Bomber Command’s long-range squadrons in 1940. In the foreground are the twisted pieces of a French Amiot 143, one of the ugliest and most vulnerable bombers deployed in any number during World War II. These same curious citizens would experience the full horrors of terror bombing in the years to come.

On September 25, 1939, the Luftwaffe launched over a thousand bomber sorties against Warsaw. Five hundred tons of explosives and incendiaries leveled entire blocks. Hospitals, schools, waterworks, and once-quiet neighborhood streets grew choked with rubble and dying civilians. The situation became intolerable. The next day, the Poles explored surrender options rather than let the slaughter of its people in Warsaw continue.

The following spring, when the Germans invaded Norway, the Low Countries, and France, the Luftwaffe employed terror bombing once again, this time to break the will of the Dutch to carry on fighting by flattening the last major industrial city not under German control. The Dutch troops defending the city were given an ultimatum to surrender or face aerial destruction. Just as the ground force commander accepted the ultimatum, the German bombers arrived. Some received a hastily sent abort order, but most did not, and downtown Rotterdam crumbled to burnt ruins under a rain of bombs.

German troops at Narvik hunker down in the snow during a British air attack. The Norway campaign was anything but an easy one for the Third Reich. Stretched to the limit of its logistical capacity to pull the invasion off, the ground forces ultimately depended on the Luftwaffe’s control of the air for close support and resupply missions, especially after the German Navy was so badly mauled in the initial invasion.

The first major strategic airlift of the war came in support of the Norway operation. The Luftwaffe, using Junkers 52 transports like the ones seen here, seized airfields with loads of troops, then brought in supplies to keep the men well provisioned with food and ammunition. It was an example of the strategic flexibility airpower offered whoever controlled the skies.

A Ju-52 tows a glider, much like the ones used to seize Fort Eben-Emael in Belgium during the assault on the Low Countries.

Hauptmann Hozzel, a well-decorated Stuka leader, poses for the camera in Norway. With the strategic seizure of airfields, the Luftwaffe was able to forward deploy close support units that helped defeat the Allied forces in the Narvik area.

The German panzer divisions poured out of the Ardennes and captured the strategically vital town of Sedan on their way to the Channel Coast. It was a significant moment, as the French had been defeated here in 1871 during the Franco-Prussian War, and the memory of that disaster lingered in the French consciousness. Seeing Sedan fall again came as a blow to national morale.

The aftermath of the fighting around Dunkirk. A British anti-tank unit has been wiped out by roving panzers.

The Potez 63.11 multi-role aircraft came in reconnaissance, light attack, night fighter, and heavy fighter variants. Hampered by ineffectual engines that lacked power, the Potez series was another failed French design. Most were destroyed in 1940, but enough survived to equip several Vichy squadrons in North Africa, where they were encountered by the United States during the Torch campaign in 1942.

The Germans march under the Arc de Triomphe in June 1940. With Paris in the Third Reich’s hands, the French cause unraveled, and its government sued for peace. It was the lowest point in France’s long and storied military history.

German pilots confer over a map prior to another mission in the West. After the fall of France, Britain fell squarely in the Luftwaffe’s crosshairs, setting the stage for the first pure air campaign in history.

Dutch Fokker DXXI fixed-geared fighters in formation. Light and agile, these well-built fighters lacked the speed of the Bf-109 and could not hold its own against the Luftwaffe’s more modern designed. However, some of them did see service with the Finnish Air Force in the 1939–1940 Winter War and took a heavy toll of Soviet Red Air Force aircraft. Over Holland the following spring, however, the Fokker squadrons could not hope to retain command of the air against the Luftwaffe’s superior numbers and more advanced fighters.

A few days later, the Germans threatened to the bomb Utrecht if the Dutch government did not surrender. Without an air force left to defend its skies from such an onslaught, the Netherlands accepted defeat and fell beneath the Nazi jackboot.

Terror bombing succeeded once again.

Against France, the Luftwaffe unleashed a concerted attack against the L’Armee de L’Air’s infrastructure. Waves of Dorniers, Heinkels, and Junkers bombers unleashed their full fury upon the French airfields and air depots. The French, whose aviation production system had all but collapsed at the end of the 1930s when the Socialists nationalized the aircraft companies, fought valiantly with obsolete equipment that the Germans simply shot out of the sky. The French managed to take a heavy toll of the attacking Luftwaffe planes, but simply did not have the numbers or the quality to stand and fight for long. Within days, the Germans had secured Douhet’s Holy Grail: command of the air. The British Army evacuated the Continent at Dunkirk, and the French did not stand a chance. After forty days of fighting, they surrendered to Hitler in the same railroad car that ended World War I.

Britain now stood alone.

The French airpower disaster remains one of the most complete defeats in aviation history. Though its brave fighter pilots did take a steady toll on the Luftwaffe, the L’Armee de L’Air suffered a complete strategic defeat at the hands of a tactically focused air force.