The USAAF banked on the B-17 Flying Fortress and its crews to deliver the knockout blows against the Third Reich. The United States invested considerable resources, money, and manpower on the creation of a strategic bombing force shaped by the B-17’s exceptional capabilities and defensive armament.

THEY CAME TO THE WAR AS FLEDGLINGS, high of spirit, confident in their aircraft, and wed to the concept of daylight precision bombing. In February 1942, just as Sir Arthur Harris took over Bomber Command, the advance wave of what would become a flood of hundreds of thousands of officers and airmen arrived in England from the United States. The Americans had arrived.

That advanced echelon included the commander of the recently activated Eighth Air Force, Maj. Gen. Carl Spaatz. A Mitchellite to the core, Spaatz appeared at Bomber Command’s headquarters at High Wycombe on February 23, 1942. He and Harris hit it off at once. They were kindred souls with unshakable faith in the ability of airpower to win the war, though they differed in the details. Thanks to the RAF’s earlier hard knocks, Bomber Command would stick to night attacks for the majority of the war. Spaatz believed that the latest-generation B-17 had all the defensive armament needed to conduct long-range missions in the teeth of Luftwaffe fighter interception. If flown in close, mutually protective formations, a B-17 group could field all-round defense with literally hundreds of deadly .50-caliber machine guns.

Through the spring, aircraft and men trickled in from the United States. It was not an impressive force at first, and on the streets of London there was much gossip about the big-talking Americans who had yet to actually measure up to their own words.

The measuring up would take time. First, the USAAF had to learn hard lessons of its own.

On Independence Day 1942, six American crews from the 15th Bomb Group (Light) climbed into aircraft borrowed from their RAF mentors in 226 Squadron. Ironically, 226 flew Douglas DB-7 “Boston” bombers, the Lend-Lease version of the venerable A-20 Havoc. For one mission, those aircraft were loaned back to the native sons of the country that provided the RAF with these excellent aerial weapons.

The Americans joined the fight in the 1942, full of confidence in the Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress. The RAF’s lessons with the early variants of the B-17 led to significant refinements that Boeing incorporated into the E model. This was not the same Fort that failed so grievously with 90 Squadron, RAF the previous year, and the E model laid the groundwork for the USAAF’s bombing campaign in Europe.

The Americans entered the European Air War on the Fourth of July 1942. Using borrowed Lend-Lease Douglas Boston bombers, a small USAAF contingent took part in a low-altitude raid on German targets in Holland. From this tiny step would spring forth thousand-plane raids that tore the industrial heart out of the Third Reich only two years later.

The Americans formed half the strike formation that day. Four Vs of three Bostons each sped low over the North Sea to target German airfields in Holland. By staying low, they sought to avoid radar detection, but Axis vessels steaming through the area spoiled their element of surprise by reporting the incoming raid.

Once the Bostons reached the Dutch coast, the formation split up and raced for their airfield targets. The Allied force flew straight into ferocious and accurate anti-aircraft fire. The Germans spared nothing when it came to airfield defense, and attacking such targets remained one of the most difficult and costly missions of the air war for low-flying tactical aircraft and fighter-bombers.

Carl Spaatz awards the Distinguished Service Cross to Maj. Charles Kegelman for his personal courage and flying skills during the USAAF’s first raid on German targets in Northwest Europe.

The Allies paid a heavy price that Fourth of July. Two of the six American crews went down in flames. A third USAAF-manned Boston took a flak hit in the engine and scraped the ground while streaking across De Kooy Airdrome. Flames feathering back from the stricken fan, the Boston pilot somehow managed to pull up and get his crew home safely, a feat that earned him a Distinguished Service Cross, the second-highest award for valor next to the Congressional Medal of Honor.

The British also lost a Boston on the mission, making this first American foray against the Germans a costly one indeed. A fourth of the bomber force succumbed to flak. It was a taste of things to come.

That summer, the first of the heavy bomb groups arrived in Great Britain. The 97th earned that honor, setting up operations at RAF Polebrook. Flying the new B-17E, the 97th lacked training, experience and tactical knowledge. Some of the navigators didn’t know how to navigate. Some of the radio operators couldn’t even read or send Morse code. Few of the men had ever conducted flights over 20,000 feet. In fact, most had never even strapped on their oxygen masks.

And yet, the 97th would serve as the seed unit for what would become the most massive air effort ever put forth by the United States. Everything has a start point, no matter how successful or not. For the Mighty Eighth, it began on August 17, 1942, when the 97th carried out a twelve-plane raid against a railroad marshalling yard at Rouen, France. Over a hundred Royal Air Force Spitfires provided heavy escort force for the bombers. Experience had shown the Luftwaffe’s fighter units in France, which included the elite Jagdgeschwader 26, could be deadly effective adversaries in their new Focke-Wulf 190 “Butcher Birds.”

Another photo of RAF Bostons during a raid on a French port.

Flying in a B-17 named Yankee Doodle on that first mission was Gen. Ira Eaker, head of VIII Bomber Command. He’d come along to see for himself how the 97th would fare. The co-pilot of Butcher Bird, the lead aircraft that day was Maj. Paul Tibbets. In 1945, Tibbets would pilot the Enola Gay over Hiroshima and his crew would drop the first atomic bomb used in battle.

The raid succeeded beyond all expectations. The dozen Forts dropped almost 40,000 pounds of British-built bombs on the target area. Post-strike reconnaissance showed an impressive, tight pattern to the destruction wrought on the ground. The Norden bombsight appeared to be a wonder device after all. Nothing the British could do at night matched this level of accuracy.

Later in August, the Eighth Air Force flew its first combat mission. Flying B-17Es, the 97th Bomb Group struck rail targets at Rouen, France, without loss. It was an auspicious beginning to what would become one of the longest attritional campaigns in U.S. history. Here, a squadron of B-17s forms up over England in preparation for a mission in 1942.

What’s more, not a single B-17 went down. All the crews returned safely to England, and there was much revelry that evening at Polebrook. There wouldn’t be many good days ahead like this one. In fact, two missions later, a Messerschmitt made a pass at Tibbetts’ B-17. A 20 mm cannon shell exploded in the cockpit, which wounded him with shrapnel and nearly took his co-pilot’s left hand off.

Still, the Rouen raid served as a good beginning for the nascent Eighth Air Force. It also made excellent propaganda and quieted the British down for awhile. To counter that English attitude, Spaatz took to carrying recon photos of strike damage in his pocket. He’d pull them out and show the results of precision bombing to anyone who wanted to take a look.

Elated at the results, Spaatz and Eaker set about laying the foundations for the massive force they hoped to field against Germany. Through the summer and fall, new bomb groups reached England, including the 303rd and 93rd. The 1st Fighter Group and its P-38s flew across the Atlantic to join VIII Fighter Command. In time, the 31st, 52nd, and 4th Fighter Groups would form the initial core of the available escort force.

The Eighth Air Force had to develop tactics, formations, and procedures almost from scratch when its crews began flying missions in 1942. Combat experience honed and refined those tactics and techniques and led to innovations from the squadron level on up.

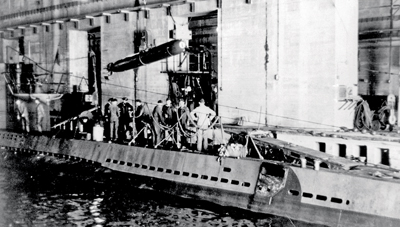

Through the rest of the fall, the Eighth Air Force devoted most of its energy against U-boat targets in support of the campaign in the North Atlantic. These deeply unpopular missions contributed little to the Allied cause. By this time, the U-boat pens in the French ports like St. Nazaire had been reinforced with a twenty foot concrete roof. The bombs the B-17s did get on these targets exploded harmlessly on the surface of these massive structures. Worse, the missions exposed the B-17 crews to heavy fighter and anti-aircraft attack. For the men who laid their lives on the line daily to carry out these sorties, such a ridiculous target selection frustrated and demoralized them.

Meanwhile, the build up gained steam until Operation Torch derailed everything. This was the invasion of Northwest Africa by a combined Anglo-American force. To carry out this operation, the Allies needed every available plane to support it. The Eighth was stripped of most of its fighter units, including the 1st, 31st, and 52nd groups, and lost some of its B-17 outfits as well. Spaatz and Eaker protested to no avail. Eventually, the Eighth lost 1,250 aircraft and 30,000 men. The bombing campaign came to a crashing halt. In December, the Eighth lost its talented commander, General Spaatz to the Mediterranean theater as well. Ira Eaker took his place It would not be until the following January that the fledglings in England would commence large-scale bombing operations against Nazi-held Europe.

As the Americans arrived in England, then had their build-up derailed by Torch, Bomber Command’s night raids began to cause substantial damage. Soon after taking over, Harris wanted to make a statement, both to the British people and to Germany, by launching the RAF’s first “thousand plane raid.” When he first floated the idea, Bomber Command possessed only about four hundred operational aircraft, the majority of which were still Wellingtons distributed among sixteen squadrons. Harris had six squadrons of Halifaxes, six more of the new and very capable Lancaster, plus two each flying Manchesters and Hampdens. To come up with the remaining aircraft for the raid, Harris had to draw on the RAF’s operational training units. Instructors and student pilots would fly side-by-side on the night of this mission.

General Ira Eaker commanded VIII Bomber Command, then later the Eighth Air Force during its formative stages through the end of the brutal 1943 campaign.

Through the 1930s, the standard USAAF bomber formation remained the elongated V. In Europe, the Fort crews realized that such an arrangement did not maximize the firepower their aircraft carried. The bomb groups began to experiment with new formations designed to give the Fort gunners overlapping fields of fire. The combat box emerged from this formative period and was widely adopted throughout the Eighth in short order.

B-17Es on a training bomb run back in the States. As the air war over Europe developed into a titanic struggle of attrition, rapid and effective crew training became one of the most important logistical elements in defeating the Luftwaffe. Eventually, the German fighter units would nearly run out of effectively prepared replacement pilots, but thanks to the system established stateside, the flow of well-trained airmen never slowed to the Eighth Air Force.

The B-17E incorporated numerous changes from the earlier variants that saw service in the Pacific and with the British. Among the most important changes was the addition of power turrets, each equipped with twin .50-caliber machine guns.

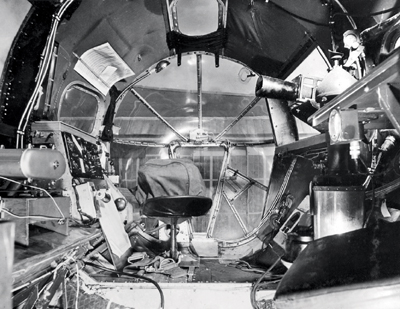

The bombardier’s compartment in the nose of a B-17. Thanks to the Norden bombsight’s linkage to the flight controls, the bombardier actually flew the aircraft from the initial point all the way to the release point with the assistance of an autopilot system.

A formation of B-17s takes shape over England well above a near total layer of clouds. Often, weather was the strategic bombing campaign’s worst enemy.

Paul Tibbets led the 97th Bomb Group’s formation during the famed August 17, 1942, mission to the Rouen railroad facilities. Later, as the commander of the 509th Composite Group, he flew the Enola Gay to Hiroshima and dropped the world’s first atomic bomb.

General Ira Eaker at his desk. After Spaatz went to North Africa, Eaker took over command of the Eighth Air Force. He lasted about a year before he was transferred to the Med.

The Eighth Air Force’s bomber crews in 1942 and early 1943 disliked bombing the German U-boat pens built in the French coastal port cities. They faced intense opposition during such attacks, and the pens were protected with reinforced concrete twenty-something-feet thick or more. The USAAF had no bomb that could penetrate such a hardened target.

Shortly before the raid began, Harris sent a message to all his group commanders and outlined what he hoped the night’s bombing would achieve.

At best the result may bring the war to a more or less abrupt conclusion owing to the enemy’s unwillingness to accept the worst that must befall him increasingly as our bomber force and that of the United States of America build up. At worst it must have the most dire moral and material effect on the enemy’s war effort as a whole and force him to withdraw vast forces from his exterior aggressions for his own protection.

On the night of May 30–31, Harris gave the go-order. From fifty-three bases all over England, 1,046 bombers lifted into the darkness, bound for the Ruhr Valley industrial city of Cologne. For hours, bombs rained down on the civilian populace. Tens of thousands took refuge in basements and cellars, bomb shelters, and other underground locations. The initial wave of attackers dropped incendiary bombs on the oldest part of the city. The flames served as a beacon for the rest of the bombers that night, and they rumbled over the city to release their loads as smoke boiled 15,000 feet into the air. The scene was soon lit with a hellish crimson glow, swathed in the acrid smoke of a city suffering immolation. The last wave of bombers could see the flames raging from over a hundred miles away.

Operation Torch, the Allied invasion of North Africa, drew away from England and Western Europe almost all the air, naval, and ground units available to the Allies in the fall of 1942. It virtually crippled the nascent American strategic bombing campaign by absorbing almost a thousand aircraft from the Eighth Air Force and ensured the invasion of France would be delayed a year.

When the thousand-plane raid was launched against Cologne in May 1942, Bomber Command fielded thirty-seven squadrons. The Wellington equipped sixteen of them and still formed the backbone of the RAF’s offensive capabilities.

After the failure of the Avro Manchester, the Lancaster emerged as the future for Bomber Command. By the time of the Cologne thousand-plane raid, Bomber Command possessed six Lancaster squadrons. After years of mediocre twin-engine and four-engine designs that proved terribly vulnerable over Germany, the RAF crews finally received an outstanding bomber with tremendous potential.

Cologne. The citizens of the city suffered terribly under the aerial punishment delivered upon their homes and factories.

Cologne burned and smoldered for days, making reconnaissance efforts almost useless. Finally, a week after the bombing, the first clear images of the city returned to England aboard fast-moving photo recon aircraft. The results staggered even Harris. Over six hundred acres of Cologne’s downtown districts had been burnt and flattened. This represented almost thirteen thousand buildings reduced to heaps of twisted rubble. Forty-five thousand residents of the city now found themselves homeless. Another five thousand suffered death or serious injury.

Harris’s optimistic view that such an attack would force an early end to the war was not realized. It didn’t matter. The future had been glimpsed by both sides, and now the British devoted ever-increasing resources toward Bomber Command while the Germans raced to bolster their night fighter force.

In August, the British established their first pathfinder squadrons. These units consisted of dedicated and well-trained crews who would lead the way each night and illuminate the target area with incendiaries. Using new electronic systems, including radar, navigation became a considerably easier prospect at night. A mission to Duesseldorf in mid-September carried out by about five hundred bombers inflicted substantial damage on the city. The RAF had hit it earlier in the summer as well, yet industrial output grew 1.8 percent over the first half of the year despite all the damage and dislocation done to the city’s infrastructure and factories.

In the fall, the Lancaster began to arrive in greater numbers until by October Bomber Command possessed nine squadrons totaling about a 175 planes. This was the aircraft of the future for the British strategic bombing effort. In the months to come, it would play the most vital role in nocturnal air war over Europe.

The growing attacks excited the RAF’s high command and energized Churchill. That fall, the Prime Minister told President Roosevelt, “We know our night bomber offensive is having a devastating effect.” The contagious optimism led Portal to conclude that the air offensive could end the war by 1944 without having to land a massive army in northwest Europe. He envisioned a campaign in 1943 and 1944 that could drop 1.25 million tons of bombs on German cities. The estimated result of such high-explosive and incendiary carnage? Portal and the Air Staff estimated it would kill nine hundred thousand German civilians, leave twenty-five million homeless and severely wound another million. The physical destruction was estimated at six million houses and near total disruption of public power and water systems, industrial capacity, and transportation routes.

The Lancaster first joined Bomber Command with 44 Squadron (pictured here) in late 1941. The unit flew its first operational sorties in the spring of 1942, just before the thousand-plane raid. Over the next three years, German defenses claimed almost 150 of 44 Squadron’s Lancasters. Twenty-two more crashed in accidents. This gave the unit an attrition rate of almost 700 percent during the climactic battles of the strategic air war.

The North African campaign drained off most of the Eighth Air Force’s strength in the fall of 1942. Almost thirty thousand air and ground crews were transferred to the primitive and hostile desert to join Doolittle’s Twelfth Air Force.

Portal wanted to kill, wound, or dislocate 75 percent of all German citizens living in cities with populations larger than fifty thousand people. It was an extraordinary and apocalyptic vision of total war on a civilian populace. And, it was the incarnation of Douhet’s central theme from Command of the Air.

The 1943 campaign would soon begin, and with it would come the first major contributions by the USAAF and its new fleet of heavy bombers. Exactly how that effort would be carried out in cooperation with the RAF dominated top-level discussions for the remainder of 1942, and during the Churchill-Roosevelt meeting at Casablanca in January 1943.

The RAF wanted the Americans to join the night bombing effort. Convert the Eighth Air Force to nocturnal operations and the Allies could have a force of thousands hitting Germany by moonlight before the end of 1943. The USAAF recoiled at the idea. The entire structure of its strategic force had been predicated on daylight precision bombing. All the Stateside training was geared toward this effort. Switching to night operations would require a wholesale reconstruction of the strategic bomber force. Hap Arnold, commander of the USAAF, could not let that happen. Yet, Churchill had already nearly sold Roosevelt on the idea of doing this.

Churchill and his senior military leaders had nearly convinced FDR to switch the Eighth Air Force to night terror bombing. General Arnold tasked Ira Eaker with saving the daylight campaign. Eaker produced one of the most stunning one-page summaries of the war for Churchill, who was spellbound by its final, memorable words.

FDR and his senior military leadership at Casablanca. The meeting between the Americans and British there shaped the future of the strategic air war for the next two years.

Eaker’s synopsis concluded, “If the RAF continues bombing at night and we bomb by day, we shall bomb them round the clock and the devil shall do the rest.” Churchill conferred with FDR, and the twenty-four-hour bombing campaign became the strategy to emerge from Casablanca.

During the Casablanca conference in January, he cabled Eaker and told him it was up to him to save the daylight bombing campaign. Eaker had majored in journalism in college. He sat down and drafted a tight, one-page summary for Churchill that outlined all the reasons why converting the Eighth Air Force to night operations would be folly. The final sentence captured the Prime Minister’s imagination.

Eaker (left) shakes hands with General Kenney, the officer who translated Douhet’s classic Command of the Air for an American audience. Eaker’s genius with words (he had been a journalism major in college) ensured the survival of the daylight bombing campaign. In a twist of irony, he himself would not survive the year as the commander of the Eighth Air Force.

“If the RAF continues bombing at night and we bomb by day, we shall bomb them round the clock and the devil shall do the rest.”

Both leaders loved the idea of “round the clock bombing.” The British would batter the Germans at night while from dawn to sunset the Americans would rule the skies. Twenty-four seven, Germany would receive no respite from the aerial bombardment.

After Casablanca, Eaker and one of his subordinates, General Hansell, sat down with two RAF counterparts and drafted a detailed plan for the 1943 air campaign. Called the Combined Bomber Offensive, the document set seventeen key target types to be attacked and destroyed during the year. The top three included: 1) the German aircraft industry, 2) ball bearings factories, and 3) Germany’s oil refining infrastructure. Harris and Bomber Command would still make destruction of German morale its key objective for the year.

For both sides, 1943 would be a pivotal period in the strategic air war. Of course, as with most wartime ventures, nothing went as planned.

General Hap Arnold shakes hands with an aviator in the MTO while General Spaatz looks on. Arnold kept a very close eye on the strategic air war in Europe, considering it the USAAF’s main effort in World War II.